Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webzines and Webpages In Archive

Master of Imaginative Fantasy Adventure

Creator of Tarzan® and "Grandfather of American Science Fiction"

Volume 7971Burroughs' Plots: Edgar Rice Burroughs has often been accused of reusing plot elements in his stories, and to some extent he did. I will here look at how Burroughs’ stories often centre around the conflict between Princess and Hero, and the resolution to that conflict.

The Hero and the Princess

By Fredrik Ekman

This article has been edited since its original publication in ERB-APA #125.

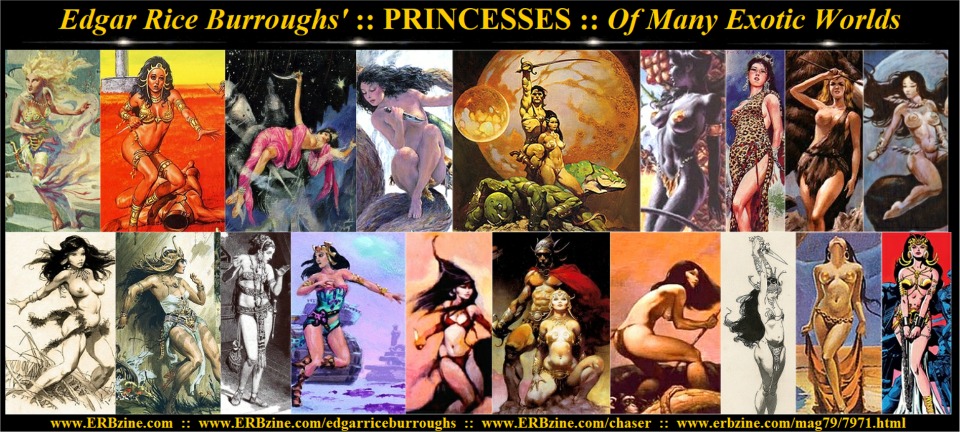

Click for full-size collageWhenever Burroughs tosses a Princess into the Hero’s way, he builds a plot around those two characters, a plot which is almost always based on the same template. There are variations, but only very rarely does he move away completely from the standard setup.

1. First Meeting

Pan Dan Chee came forward rather open-mouthed and goggle-eyed. “Llana of Gathol!” he whispered as one might voice the name of a goddess. (LG-1/10)At the time of the first meeting between Hero and Princess, the Hero is normally a visitor of an exotic tribe or people, either as their guest or prisoner. The Princess is either a member of that tribe, or she is a captive from a competing (and more advanced) society.

This first meeting is practically always very emotionally tense. The Hero is usually the one who sees the Princess first, and he either falls in love immediately, or is at least very interested in her, whereas she usually remains a lot more distanced. Sometimes she hides her true feelings, sometimes she needs time to develop them.

In many cases, the title of the chapter where the Hero first meets his Princess is the same as her name, foreshadowing the important part that she is destined to play in the story.

A rare variant on this theme is when the Princess is temporarily the story’s protagonist, and she is actually the one to first lay eyes on the Hero, not the other way around. This happens when Princess Tara meets Gahan of Gathol (CM/1), but it is still the Hero who falls in love and the Princess who keeps her distance.

In Burroughs’ world, it is always the Hero who is the active lover, and it is not rare that within five minutes of their first meeting, the Hero has already declared his undying love of the Princess

2. Alienation

Again she stamped her foot angrily. “Thou art indeed a forward boor,” she exclaimed. “I shall not remain to be insulted further.”

Her head held high she turned and walked haughtily away to rejoin the other party. (LJ/11)There is often an unspoken undercurrent of cultural conflict in Burroughs’ works, and the Princess plot is an embodiment of this conflict. It is the conflict between progressive civilisation (represented by the Hero, who is usually a male American or European), and the Wild (represented by the Princess, who is either from an uncivilised tribe, or from an extra-terrestrial people; in many cases both of the above).

The path to happiness is trip-wired with cultural clashes, and one of these is bound to go off sooner or later. The classic example is when John Carter tells Dejah Thoris that he has fought for her (PM/14), not realizing that since he has not also asked for her hand in marrige, he is implying that she is a lower class of woman.

This conflict is always resolved in the end, and the reason that it can be resolved at all is that even though the Hero is superior due to his civilised background, the Princess is nearly his equal because of her royal blood.

3. Consolidation and Separation

So we made our camp beside the river and dined on juicy chops, delicious fruits, and the clear water from the little stream. Our surroundings were idyllic. Strange birds sang to us, arboreal quadrupeds swung through the trees jabbering melodiously in soft sing-song voices. (LV/8)Around this point in the plot, there is often a period of calm and consolidation, as the pace slows down. Our main characters, while getting to know one another, live or travel alone in the wilderness, depending upon each other for survival. If he has not done so already, the Hero speaks about his true Love for the Princess. Even if the Princess has seemed attracted to him previously, he is always refused, although later we learn that the Princess was beginning to weaken. It is also common for the Hero to proclaim that he understands she can never love him, and he demands that she only let him protect her, never fearing that he would let himself be overpowered by his emotions. (In other words: “I promise that I am not going to rape you, if you just let me stay by your side.”)

Unfortunately, before she really starts to return the Hero’s feelings, the couple are separated by external forces. Usually, she is kidnapped.

This third phase may sometimes be repeated multiple times, taken to its extreme in the Venus series, where Carson and Duare are separated no less than seven times. First Carson is kidnapped by klangan winged men (PV/8); then Duare is captured by the quasi-communist Thorists (PV/13); after which Carson himself meets the same destiny (PV/14); then both are captured and separated in the castle of Skor (LV/9); Duare is then sentenced to death by the scientists in Havatoo (LV/21); and when she has been rescued from that, she is kidnapped by the warrior women of Houtomai (CV/1); eventually, Carson is ordered to go on a secret mission for the janjong (king) Muso (CV/6). Only at this point, after about two and one half novels, is this over-the-top plot ready to move on to the next inevitable step, as Carson manages to return from his “impossible” mission (CV/13) just in time for phase 4.

Though a few other stories do feature multiple separations, the norm is for a single one, such as the kidnapping of Princess Guinalda (LJ/18).

4. A Fate Worse than Death

“Kiss me once more, Julian,” she said, “and then the dagger.”“Never, never, Nah-ee-lah!” I cried. “I cannot do it.” (MMa-1/14)

The termination of the (last) separation between Hero and Princess is often the climactic moment of the plot. A major villain is threatening the Princess (usually having kidnapped her) and intends to take advantage of the situation, and of the girl, too.

In some cases, the Princess plot climax is not a mere rape threat, but a forced wedding, complete with ceremonies, guests and all. I call this the perfect Princess plot. In Carson on Venus, Burroughs even invents a special marriage ceremony on a world where marriage does not exist, in order to make his plot perfect: “A jong [king] … must take his woman before the eyes of all men; so that all may know whom to honor as their vadjong [queen].” (CV/13)

Whether a rape attempt or a forced wedding, the implication is that the Princess’ honour is about to be soiled for the rest of her life. Burroughs implies that after this terrible event, the Princess will be forever spent and useless. She cannot ever have the Hero if she is thus defiled, and we can assume that she will be outcast from her family and tribe.

Consequently, she often considers taking her own life, or sometimes she asks the Hero to take it for her. If she can get a weapon, she reserves it for herself, rather than attempt to fight with it. In Burroughs’ imaginary worlds, honour is worth more than a human life. If she is not contemplating suicide, she has at this point become completely passive.

Ah, but of course. When everything looks hopeless, there comes the Hero to the rescue. Often by force, sometimes with allies, but sometimes he only uses the power of the word to win, such as when Gahan of Gathol (as Turan) together with I-Gos convinces the assembled nobles that their jeddak is a coward and a liar (CM/23).

In a rare twist of this plot element, Princess O-aa actually kills her would-be rapist herself, rather than wait for the arrival of the Hero (SP-2/3).

This section is usually not the end of the book. It is often the climax, and in many cases only some loose ends need to be tidied up. But in other cases, the story will go on for quite a few chapters yet.

Exceptions

According to my count, eighteen Burroughs stories contain Princess love interests (counting the first three Venus novels as one story, and ignoring The Gods of Mars and The Warlord of Mars, which contain Princess plot elements, even though the plot has been acted out already in A Princess of Mars). Depending on how you count, that is about 20% of Burroughs’ total output, so one story out of five has a Princess.Nine stories fit the Princess plot template perfectly: A Princess of Mars, The Chessmen of Mars, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, At the Earth’s Core, Tanar of Pellucidar, Back to the Stone Age, Savage Pellucidar, The Moon Maid and The Pirates of Venus (together with Lost on Venus and Carson of Venus).

It is worth pointing out that the Princesses in Back to the Stone Age and Tanar of Pellucidar are never formally stated to be “princesses”. Both are daughters of tribal chiefs, rather than proper kings, but since both stories otherwise follow the plot template, I think it is reasonable to include them here.

Two other stories are slight variations of the plot, as it is not the Hero but his sidekick who falls in love with the princess in Tarzan the Terrible and Llana of Gathol. This forces some differences, as the sidekick will have to replace the Hero in some plot elements, whereas the Hero remains as the active party in others.

Four stories contain incomplete plots: Jungle Girl has no Alienation. In Thuvia, Maid of Mars, an assassination attempt replaces the Fate Worse than Death. A Fighting Man of Mars only retains the end of the plot, starting with Consolidation. There is a First Meeting, but not typical, since the Hero does not immediately fall in love. This is understandable. The reader and the Hero, indeed even the Princess herself, do not know that she is a true Princess until just near the end. Falling in love with someone who is (apparently) not a Princess naturally takes more time. A similar development can be seen in The Son of Tarzan; not only is Korak’s Princess not revealed to be a Princess, but she is also under age. But even though love is impossible at the first meeting, there is definitely mutual interest. The falling-in-love thing occurs much later, as a coming of age rite for Korak. As in A Fighting Man of Mars, there is no proper alienation in The Son of Tarzan.

Only three Princesses as love interests do not easily form themselves into the mould:

The Princess in Tarzan and the Antmen falls in love with Tarzan while also being loved by another. This love triangle is actually part of a different plot template Burroughs sometimes used.

Beware! is so short that there is no time to develop the Princess plot. There are some traces of it, but no First Meeting, no Consolidation, and the other elements are very sketchy. Beware! was originally published as The Scientists Revolt, heavily edited by Ray Palmer. In that version, the Princess had been demoted to a simple “War Minister’s daughter”.

The Master Mind of Mars contains all the plot elements, but mixed up. For example, the attempt to force Ulysses Paxton’s Princess into marriage is part of her background (MMM/4), not something that the Hero stops in the last minute.

Conclusions

This analysis only deals with Princesses. The Princess plot elements may or may not be applicable to other Burroughs femmes, e.g. Tarzan’s Jane. Closer examination would perhaps reveal many similarities, but also differences. For whatever reason, Burroughs had a special eye to his Princesses.Another interesting aspect is how this plot relates to other popular authors or genres. What about contemporary pulp authors? What about modern Hollywood? What about folk tales or classical Greek dramas? Or in other words: To what extent did Burroughs rely on ancient story-telling devices, and to what extent did he invent new ones that may have been picked up by others?

The Princess plot, in this analysis, seems shallow, and in a sense it is. But then it was only the bare bones, upon which Burroughs fleshed the intricate pattern of the full story. With subplots, characters, environments, and not least his beautiful language holding it all together.

Sources

Romances with Princesses occur in the following stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Open the ERBzine links in our ILLUSTRATED ERB BIBLIOGRAPHY

to see the full coverage of each title plus full e-text for most editions

• A Princess of Mars (PM)

• Thuvia, Maid of Mars (TMM)

• The Chessmen of Mars (CM)

• The Master Mind of Mars (MMM)

• A Fighting Man of Mars (FMM)

• Llana of Gathol (LG)

• The Son of Tarzan (ST)

• Tarzan the Terrible (TTe)

• Tarzan and the Antmen (AM)

• Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle (LJ)

• At the Earth’s Core (AEC)

• Tanar of Pellucidar (TP)

• Back to the Stone Age (BSA)

• Savage Pellucidar (SP)

• Beware! (B)

• The Moon Maid (MMa)

• Jungle Girl (JG)

• The Pirates of Venus (PV)

• Lost on Venus (LV)

• Carson of Venus (CV)

This article is featured in our

Fredrik Ekman Tribute Series

BILL HILLMAN

Visit our thousands of other sites at:

BILL and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All Original Work ©1996-2024 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective owners