Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Volume 8087

Newspapers in the

Fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs I

<>This is Part One of Alan Hanson's summary of how Edgar Rice Burroughs used the subject of newspapers in his fiction.

Part One covers the topic in ERB's stories written from 1912 to 1923.

Part Two will address the newspaper theme in his works of fiction written from 1924 through 1940.

NOTE: Each title contains a hot link to my ERB Bibliography in ERBzine ~

Featuring cover & interior illustrations, publishing history, reviews, e-text edition, etc. for each edition

~ Bill Hillman

Edgar

Rice Burroughs lived through the golden age of American newspapers.

Like most

Americans in the mid 20th century, his adult life, both

private and

professional, was attuned to the rhythms of the daily print media. An

entire

volume could be written describing the various ways the author’s life

was

intertwined with newspapers. Just a few examples follow.

When,

as a young man, Burroughs was living in Idaho, his brother Harry backed

him in

opening a stationary store in Pocatello. It included a large newsstand.

“I had

a newspaper route and I delivered newspapers myself on horseback,”

Burroughs

recalled in a 1929 Los Angeles Times

article.

In

another 1929 article, “How I Wrote the

Tarzan Books,” published in The New York World

newspaper’s Sunday

supplement, Burroughs credited that newspaper for the book publication

of Tarzan of the Apes.

“It’s

popularity and its final

appearance as a book was due to the vision of J. H. Tennant, editor of

The New

York Evening World. He saw its possibilities as a newspaper serial and

ran it

in The Evening World, with the result that other papers followed suit.

This

made the story widely known and resulted in a demand from readers for

the story

in book form, which was so insistent that A. C. McClurg & Co.

finally came

to me after they had rejected it, and asked to be allowed to publish

it.”

Four

other Burroughs serials appeared in The

Evening World before McClurg finally published Tarzan

of the Apes in June 1914. They were The Cave Girl,

The Return of

Tarzan, The Eternal Lover, and At the

Earth’s Core. Burroughs also

profited from the sale of newspaper serial rights for other stories he

wrote,

especially in the early years of his career.

Burroughs

wrote many other articles for newspapers. Most notable were a couple of

serial

columns. Starting on January 26, 1928, he wrote 11 columns for the Los Angeles Examiner about daily

developments in the sanity hearing of William Hickman, the confessed

killer of

a 12-year-old girl. Years later, while living in Honolulu during World

War II,

Burroughs wrote a series of “Laugh It Off!” articles, which appeared in

the

city’s two newspapers, the Star-Bulletin

and the Advertiser. He also penned a

number of news dispatches during his travels around the Pacific theater

as a

war correspondent.

Burroughs

described his relationship with the press through the years in a 1930

article

in Writer’s Digest. “I have had close

personal and business relations with newspapermen all over the United

States,

both publishers and editors, numbering among them many good friends.

Yet I have

never directly or indirectly, asked or expect any personal publicity

from them;

nor have I ever paid for any publicity.”

Given

the importance of newspapers in his life, then, it’s not surprising to

find so

many references to them in his fiction. Newspapers are mention in over

30 of

Burroughs’ stories. Some are mere remarks made in passing, while a few

others

are so extensive as to make a newspaper a de facto character in the

story.

The

use of newspapers in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ fiction is summarized below

by story

in chronological order of its writing. Presenting them so provides some

insight

into the evolution of Burroughs’ attitude toward newspapers over the

years.

The Avenger was one of

Burroughs’

first works of fiction. The short story, written in early 1912, first

appeared

in Forgotten Tales of Love and Murder,

published by John Guidry and Pat Adkins in 2001. It chronicles a

fateful day in

the life of Joseph Stone, who, while on a business trip in Pittsburgh,

received

a cryptic note, which he interpreted as a warning that his pregnant

wife was

entertaining a lover at their home in an unnamed city. Stone hurried

home in

time to discover a strange man descending the stairs in his home.

Enraged,

Stone attacked and killed his wife’s suspected lover. To complete his

revenge,

Stone disfigured the victim’s face and changed clothes with him,

leaving his

wife to think her lover had killed her husband. Stone then fled the

scene to

spend the night in small hotel in a city a hundred miles away.

JOSEPH STONE BRUTALLY MURDERED

Mystery Surrounds Crime

Doctor Suspected

Motive Unknown

The text below the headline

is a classic

example of a “straight news story,” presenting the known facts of the

case in

descending order of importance. The story’s “lead” contains the

required “who,”

“what,” “where,” “when,” “why” (unknown as of then), and “how.”

The

body of the article reveals that the police believed Stone’s deception

that he

was the murder victim. However, the article then explained that the man

whom

Stone killed was not his wife’s lover, but instead a doctor who was in

the home

attending to the delivery of Mrs. Stone’s baby. It was the doctor’s

nurse who

sent the note to Stone in Pittsburgh summoning him home for the birth.

Both

the news article and the story end with the following sentence about

the

weakened condition of Mrs. Stone. “Otherwise, she is doing well, as is

the

little son who was born to her last night.” Burroughs then left it up

to the

reader to predict John Stone’s reaction to what he read in the

newspaper that

morning.

Once

all the principal characters arrived in Paris, Rokoff and Paulvitch

hatched a

new plot, which again involved the Paris press. For days the Russians

watched

the papers. “At length they were rewarded,” Burroughs noted. “A morning

paper

made brief mention of a smoker that was to be given on the following

evening by

the German minister.” That evening the conspirators lured Tarzan to

Olga’s

boudoir, hoping to tempt the two into a romantic encounter that they

could use

to pressure Olga for information. “What shall we do, Jean?” she asked

Tarzan.

“Tomorrow all Paris will read of it. He (Rokoff) will see to that.”

Meanwhile,

Rokoff and Paulvitch had returned to their rooms. “They had telephoned

to the

offices of two of the morning papers from which they momentarily

expected

representatives to hear the first report of the scandal that was to

stir social

Paris on the morrow.” Tarzan arrived before the newspapermen, however,

and

forced the Russians to promise, “upon pain of death, that you will

permit no

word of this affair to get into the newspapers.” A young man from the Martin soon arrived. When he said, “I

understand that Monsieur Rokoff has a story for me,” Tarzan responded,

“You are

mistaken, monsieur. You have no story for publication, have you, my

dear

Nikolas?” Noticing the “nasty light” in the ape-man’s eye, Rokoff sent

the

reporter away. It was not the last time the two scoundrels would

conspire

against Tarzan, but none of their future plots involved spreading false

rumors

through newspapers.

Begun

by ERB in late 1913 and finished in early 1914, The Cave

Girl chronicles the transformation of Back Bay aristocrat

Waldo Emerson Smith-Jones into a cave man following being castaway on a

South

Seas island. Two months after Waldo set out on a long sea voyage, the

following

short article appeared in a Boston newspaper.

“The

captain reports that the great

wave swept entirely over the steamer, momentarily submerging her. Two

members

of the crew, the officer upon the bridge, and one passenger were washed

away.

The latter was an American traveling for his health, Waldo E.

Smith-Jones, son

of John Allen Smith-Jones of Boston. The steamer came about, cruising

back and

forth for some time, but as the wave had washed her perilously close to

a

dangerous shore, it seemed unsafe to remain longer in the vicinity, for

fear of

a recurrence of the tidal wave which would have meant the utter

annihilation of

the vessel upon the nearby beach. No sign of any of the poor

unfortunates was

seen. Mrs. Smith-Jones is prostrated.”

Written

in the same 1913-14 period, The Girl From

Farris’s was ERB’s first attempt at exposing corruption in his

hometown of

Chicago. In the story, Burroughs used sarcasm to censure the city’s

newspapers

for helping spread phony religion-based progressive principles. The

prime

purveyor of those theories in the story is the Rev. Theodore Pursen,

who is

first seen at his breakfast table reading his preferred daily

newspaper, the Monarch of the Morning. Pursen

commented

on the paper’s content to his assistant.

r of a

column

devoted to an interview with me on the result of my investigation of

conditions

in supposedly respectable residence districts. The article has been

given much

greater prominence than that accorded to the misleading statements of

the

assistant State attorney. I am sure that thousands of people in this

great city

are even this minute reading this noticeable heading—let us hope that

it will

bear fruit, however much one may decry the unpleasant notoriety

entailed.”

The

headline over the article read, in large letters, “PURSEN PILLORIES

POLICE.”

With this opening view of Pursen, Burroughs implied that, on the

contrary, the

good reverend very much enjoyed seeing his name in print, no matter how

much he

claimed to decry it.

After

learning of Maggie Lynch’s arrest in the red light district, Pursen,

with three

men in tow, went to the city jail to talk with her. “I come as a

friend,” he

announced. “Tell me your story, and we’ll see what can be done.” Maggie

eyed

the other three young men. “Representatives of the three largest

papers,”

Pursen confirmed. “You will be quite famous by tomorrow morning.”

Pegging

Pursen as a publicity seeker, she invited him to get lost.

Pursen

didn’t forget the humiliation the woman had heaped on him in front of

the three

reporters. “He flushed at the memory of the keen shafts of ridicule

that had

resulted,” Burroughs stated, “and which had made the papers of the

following

day such frightful nightmares to him.”

Early

in the story, businessman Ogden Secor (later to be Maggie’s benefactor,

and she

his) voiced his opinion of Reverend Pursen. “I’ve met him here perhaps

a half

dozen times— here, and in the newspapers. About all I’ve noticed about

him is

the poor, weak way he has of getting into print.”

Although

charges against Maggie Lynch’s involvement in the murder of a man were

dropped,

for some unknown reason they were later reinstated after she had

regained a

respectful reputation under the name June Lathrop. Burroughs implied it

was an

unsavory Chicago newspaper that gave the story new life.

“A

scarehead morning newspaper had

used it as an example of the immunity from punishment enjoyed by the

powers of

the underworld—showing how murder, even, might be perpetrated with

perfect

safety to the murderer. It hinted at police indifference—even at police

complicity.”

Fortunately,

in this instance, the case was not tried in the press, and June was

found

innocent.

Near

the end of part one of The Mucker,

written in 1913, protagonist Billy Byrne made a name for himself in the

New

York City boxing scene. When he knocked out the reigning “white hope,”

he

caught the attention of the city’s sports scribes.

“The

following morning the sporting

sheets hailed, ‘Sailor’ Byrne as the great ‘white hope’ of them all.

Flashlights of him filled a quarter of a page. There were interviews

with him.

Interviews with the man he defeated … All were agreed that he was the

most

likely heavy since Jeffries. Corbett admitted that, while in his prime

he could

doubtless have bested the new wonder, he would have found him a tough

customer.”

After

reading and rereading his press clippings, Billy spotted a familiar

name in

another section of the paper—Harding. “Persistent rumor has it that the

engagement of the beautiful Miss Harding to Wm. J. Mallory has been

broken,”

the social notice read. “Miss Harding could not be seen at her father’s

home up

to a late hour last night. Mr. Mallory refused to discuss the matter,

but would

not deny the rumor.”

Meanwhile,

far uptown Barbara Harding was scanning the same newspaper sports

section for

the scores of yesterday’s women’s golf scores, when her eyes suddenly

riveted

on a picture of a giant boxer. Searching the headlines and text, she

finally

came upon his name—“Sailor Byrne.”

She knew it must be the man she had fallen in love with during a South

Seas

adventure. Billy then called on Barbara and urged her to marry Mallory.

A few

weeks later, a lonesome and friendless Billy read the following

newspaper item in

his Chicago jail cell. “The marriage of Barbara, daughter of Anthony

Harding,

the multimillionaire, to William Mallory will take place on the

twenty-fifth of

June.”

Confident

in his innocence, Billy had gone to Chicago in part two of The

Mucker, written in 1916, to turn himself in on a murder

warrant. Now he found himself again in the newspapers, this time the

victim of

over-zealous crime reporting, which had put heat on the police.

At

her Riverside Drive home in New York City, Barbara Harding spotted a

headline

in her morning newspaper. “CHICAGO MURDERER GIVEN LIFE SENTENCE.” The

lead-in

read, “Murderer of harmless old saloon keeper is finally brought to

justice.

The notorious West Side rowdy, ‘Billy’ Byrne, apprehended after more

than a

year as a fugitive from justice, is sent to Joliet for life.” (She

didn’t know

that by that time Billy had jumped from the prison train and escaped.)

While

on the lam, Billy partnered-up and bummed across the mid-West with

Bridge. A

few miles out of Kansas City, Billy earned a handout by doing odd jobs

for a

restaurant owner in a small town. The food he gave Billy was wrapped in

a copy

of the Kansas City Star. When Bridge

unwrapped the food, an article in the newspaper caught his attention.

“Hastily

Bridge tore from the paper the article that had attracted his interest,

folded

it, and stuffed it into one of his pockets.” Later Billy found the

article on a

washroom floor and read it.

“Billy

Byrne, sentenced to life

imprisonment in Joliet penitentiary for the murder of Schneider, the

old West

Side saloon keeper, hurled himself from the train that was bearing him

to

Joliet yesterday, dragging with him the deputy sheriff to whom he was

handcuffed.

The deputy was found a few hours later bound and gagged, lying in the

woods

along the Santa Fe not far from Lemont. He was uninjured. He says that

Byrne

got a good start, and doubtless took advantage of it to return to

Chicago,

where a man of his stamp could find more numerous and safer retreats

than

elsewhere.”

There

was much more information in the article. It detailed the crime of

which Billy

had been convicted, summarized his long criminal record, and mentioned

a $500

reward being offered for information leading to his arrest. At first

suspicious

of Bridge’s motive for keeping the clipping, Billy soon became

convinced he

could trust his friend not to turn him in.

Chicago

police officer Flannagan had been trailing the escapee for some time.

When he

finally caught up to Billy, though, he told him that another man had

confessed

to Schneider’s murder and that the Illinois governor had pardoned Billy

10 days

ago. Billy didn’t believe it, until Flannagan showed him an article

from the

“Trib” (presumably the Chicago Tribune)

that confirmed it.

In

part one of The Mad King, written in

1913, American Barney Custer unintentionally gets involved in the

political

machinations of the mythical Balkan kingdom of Lutha. At end of part

one, he is

forced to flee that country. As part two opens, various forces cause

him to

return to Lutha. Having left an outlaw, however, he needed a legal way

of

getting into the country. Leaving his Nebraska home, Barney went to New

York

City to seek a “commission as correspondent” from an old classmate who

owned

the New York Evening National

newspaper. After agreeing to pay all his expenses and to forward to the

paper

“anything he found time to write,” Barney received the credential he

sought.

His

press papers earned him passage through Italy and Austria-Hungary into

Lutha. Evidently,

Barney’s adventures while there never allowed time for him to write

press

reports for the newspaper in New York.

Originally

written by Burroughs in 1914, The Lad and

the Lion was expanded by the author in 1937 for book publication.

Its

setting is a mythical kingdom in Northern Africa. In the story,

Burroughs used

newspapers as a conduit for information flowing in and out of the

politically

volatile principality.

For

example, in the following passage, Hans de Groot, son of the royal

gardener,

learns of the death of a conspirator. “‘Your friend, Carlyn, was killed

last

night,’ said one of (the officers). ‘Here it is in the morning paper.

He was

shot by a woman in her room in a hotel on the frontier.’ Hans took the

paper

and read the brief article.”

In

the story’s final chapter, Burroughs pulled all elements of the story’s

intrigue together and summarized them for the reader in a periodical

news

story.

“Magazines

from civilization seep

into many far corners of the world. One such, an illustrated weekly of

international renown, found its way into the douar of an Arab sheik.

The

son-in-law of Ali-Es-Hadji was reading therein an account of the

strange happenings

in a far-off kingdom. He read of the assassination of King Ferdinand

and Hilda

de Groot, and he examined with interest their pictures and pictures of

the

palace and the palace gardens. There was a full page picture of General

Count

Sarnya, the new Dictator. There was also a picture of an elderly,

scholarly

looking man, named Andresy, who had been shot with many others by order

of

Sarnya, because they had attempted to launch a counter-revolution.”

<>

Meanwhile,

out of French colonial North Africa came a brief newspaper article

about the

kidnapping of a French officer’s seven-year-old daughter. That obscure

article

would run like a thread through the story of Tarzan’s lost son, until a

decade

later it would bring Lord Greystoke and Captain Armand Jacot together

with

their lost children.

Shiek

ben Khatour, the kidnapper of Jeanne Jacot, renamed her “Meriem” and

claimed

she was his daughter. He kept her captive as his Arab band wandered in

sub-Saharan Africa. About a year after her kidnapping, the curious

Meriem found

a box while secretly looking through the possessions of a Swede

visiting the

Shiek’s camp. She found the following items in the box.

“There were

letters and papers and

cuttings from old newspapers, and among other things the photograph of

a little

girl upon the back of which was pasted a cutting from a Paris daily—a

cutting

that she could not read, yellowed and dimmed by age and handling—but

something

about the photograph of the little girl which was also reproduced in

the

newspaper cutting held her attention. Where had she seen that picture

before?

And then, quite suddenly, it came to her that this was a picture of

herself as

she had been years and years before. Where had it been taken? How had

it come

into the possession of this man? Why had it been reproduced in a

newspaper?”

Before

creeping away, Meriem stuck the picture and newspaper article in her

waist belt.

Over the next few years, she showed the clipping to several people, and

each

time, unknown to her, it brought her closer to a reunion with her

father. After

she took the clipping, the first to see it was Abdul Kamak, a young

Arab in the

Shiek’s band.

“She drew

the photograph from its

hiding place and handed it to him. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘it is you, but

where was it

taken? How does it happen that The Sheik’s daughter is clothed in the

garments

of the unbeliever?’

“‘I do not

know,’ replied Meriem …

He turned the picture over and as his eyes fell upon the old newspaper

cutting

they went wide. He could read French, with difficulty, it is true; but

he could

read it … Slowly, laboriously he read the yellowed cutting. His eyes

were no

longer wide. Instead they narrowed to two slits of cunning. When he was

done he

looked at the girl. ‘You have read this?’ he asked. ‘It is French,’ she

replied, ‘and I do not read French.’”

Ten

years after his daughter’s disappearance, Captain Jacot, who had still

not

given up searching for his lost Jeanne, came to London to seek the help

of Lord

Greystoke. As he explained, it was the newspaper clipping that Meriem

took in

the Swede’s tent years before that led him to Tarzan.

“‘Her

picture was published in the

leading papers of every large city in the world, yet never did we find

a man or

woman who ever had seen her since the day she mysteriously disappeared.

A week

since there came to me in Paris a swarthy Arab, who called himself

Abdul Kamak.

He said that he had found my daughter and could lead me to her. I took

him at

once to Admiral d’Arnot, whom I knew had traveled some in Central

Africa. The

man’s story led the Admiral to believe that the place where the white

girl the

Arab supposed to be my daughter was held in captivity was not far from

your

African estates, and he advised that I come at once and call upon

you—that you

would know if such a girl were in your neighborhood … The fellow had

only an

old photograph of her on the back of which was pasted a newspaper

cutting

describing her and offering a reward.’

“The

General drew an envelope from

his pocket, took a yellowed photograph from it and handed it to the

Englishman.

Tears dimmed the old warrior’s eyes as they fell again upon the

pictured

features of his lost daughter. Lord Greystoke examined the photograph

for a

moment. A queer expression entered his eyes. He touched a bell at his

elbow,

and an instant later a footman entered. ‘Ask my son’s wife if she will

be so

good as to come to the library,’ he directed.”

Thus,

a ten-year old, yellowed photo, with a short article from a Paris

newspaper on

the back, finally reunited Captain Jacot with his lost daughter.

Hemmington

Main, a star reporter on a “great metropolitan daily” newspaper, wanted

to

marry Gwendolyn Bass, daughter of New York millionaire Abner J. Bass in

ERB’s

1915 novelette. Gwendolyn was willing, but her social-climbing mother

took her

to Europe hoping to find a royal match for her there. Hemmington

followed,

looking for an opportunity to press his suit with Gwendolyn. There Main

became

involved in switching identities and other intrigue involving the royal

houses

of the tiny nation states of Karlova and Margoth. Burroughs used

newspapers to

keep Main—and the reader—informed about his plan’s unintended

complications.

The first indication Main had that his tactics had misfired was when he

read a

newspaper in his hotel lobby.

“Vying with

one another for

importance were two news items upon the front page. One reported the

abduction

of Princess Mary of Margoth by the notorious Rider, and her subsequent

rescue

by the royal troops. Main whistled as he read of the capture of the

famous

bandit and the probable fate which was in store for him. Further along

in the

account of the occurrence was another item which brought a second

whistle to

the lips of the American. ‘Princess Mary,’ it read, ‘insists that The

Rider did

not know her true identity until after the royal troops had rescued her

and

captured the brigand … the names of Mrs. Bass and her daughter also

appear, as

well as that of Hemmington Main, an American newspaper man.’”

When

Hemmington read the next sentence, he knew he, Gwendolyn, and her

mother were

in big trouble. “Margoth is anxious to demonstrate her friendship and

sympathy

for Karlova,” it read, “by cooperating with her in every way in the

apprehension and arrest of the conspirators.” All three of the

Americans were

soon arrested. The whole cast eventually escaped punishment, and though

all the

characters ended up marrying the right people, the local newspaper

reporters

never seemed to figure out what really happened.

“The Oakdale Affair,” written

by Burroughs in

1917, was an offshoot of “The Mucker,” finished the year before. In the

short

story, Burroughs showed how a small-town newspaper could fire up its

readers

with sensational reporting about a series of major crimes.

Writers

for the Oakdale Tribune must have

been ecstatic when the story of a lifetime surfaced in their sleepy

mid-West

community in the spring of 1916. Burroughs recounted how the Tribune reported four mysterious crimes,

all of which were committed the day before in their community.

“The

following morning all Oakdale

was thrilled as its fascinated eyes devoured the front page of

Oakdale’s

ordinarily dull daily. Never had Oakdale experienced a plethora of

home-grown

thrills; but it came as near to it that morning, doubtless, as it ever

had or

ever will.

“There was,

first, the mysterious

disappearance of Abigail Prim, the only daughter of Oakdale’s

wealthiest

citizen; there was the equally mysterious robbery of the Prim home.

Either one

of these would have been sufficient to have set Oakdale’s multitudinous

tongues

wagging for days; but they were not all. Old John Baggs, the city’s

best-known

miser, had suffered a murderous assault in his little cottage upon the

outskirts of town and was even now lying at the point of death in The

Samaritan

Hospital.

“Yet even

this atrocious deed had

been capped by one yet more hideous. Reginald Paynter had for years

been looked

upon half askance and yet with a certain secret pride by Oakdale. He

was her

sole bon vivant in the true sense of the word, whatever that may be. He

was

always spoken of in the columns of the Oakdale Tribune as ‘that well

known

man-about-town,’ or ‘one of Oakdale’s most prominent clubmen.’ Reginal

Paynter

was dead. His body had been found beside the road just outside the city

limits

at mid-night.”

The

work of the Oakdale Tribune,

according to Burroughs, was far from done that day. The bit was in the

editor’s

mouth, and he responded by charging forward with innuendo and

speculation.

“The

Oakdale Tribune got out an

extra that afternoon giving a resumé of such evidence as had

appeared in the

regular edition and hinting at all the numerous possibilities suggested

by such

matter as had come to hand since. Even fear of old Jonas Prim and his

millions

had not been enough to entirely squelch the newspaper instinct of the

Tribune’s

editor. Never before had he had such an opportunity and he made the

best of it,

even repeating the vague surmises which had linked the name of Abigail

to the

murder of Reginald Paynter.”

Willie,

an imaginative local boy, overheard Bridge, ERB’s poet-vagabond, and a

youngster going by the name of “The Oskaloosa Kid” discussing the

crimes. “He

saw not only one reward but several and a glorious publicity which far

transcended the most sanguine of his former dreams. He saw his picture

not only

in the Oakdale Tribune but in the newspapers of every city of the

country.”

After hearing Willie’s story, the police arrested Bridge and the Kid

for the

crimes. Sitting in the Oakdale jail, they could hear a sullen crowd

outside

working itself into a lynch mob.

It

was a newspaper that Bridge found in their jail cell that suddenly made

him

realize how he could save both of them.

When

Bridge saw a picture of Abigail Prim in the paper, he suddenly realized

that

“The Oskaloosa Kid” was really the supposed kidnap victim. Since it was

no

crime for Abigail to take her own jewels, the Oakdale

Tribune and the community’s disappointed citizens returned

to their dull small-town ways. Still, it was an exciting three days of

Oakdale,

thanks the town newspaper.

Burroughs

mentioned newspapers directly in part one (1917) of The

Moon Maid (and indirectly in part two (1919). In his tale of

future interplanetary contact, narrator Julian 3rd told of

the great

excitement caused on Earth when contact with inhabitants on Mars was

first made

in the year 1967. It was not until the year 2015, however, that the

first

manned ship between the planets was launched. During the period

(1967-2015) of

wireless-only contact between the two planets, “Knowledge was freely

exchanged

to the advantage of both worlds,” Julian 3rd explained.

“Martian

news held always a prominent place in our daily papers from the first.”

Following

the Moon Men’s invasion and conquering of the Earth, beginning in 2050,

newspapers ceased to exist on Earth because the technology to create

them

disappeared. The despotic hand of the Moon Men and their descendants

instituted

a crushing campaign of thought control. Not only newspapers, but also

all other

forms of printed matter were banned. Julian 9th described

the result

of that austere policy by the time he turned 20 in 2120. “Printing was

a lost

art and the last of the public libraries had been destroyed almost a

hundred

years before I reached maturity, so there was little or nothing to

read.”

Written

in 1919, The Efficiency Expert has

parallels to ERB’s struggles in Chicago just a few years earlier.

Before he

turned to writing fiction, Burroughs, in search of work to support his

young

family, had answered many “help wanted” newspaper ads with no results.

In The Efficiency Expert, lead character

Jimmy Torrance comes to Chicago searching for work in the same way,

with the

same results.

“In the

lobby of the hotel he

bought several of the daily papers, and after reaching his room he

started

perusing the ‘Help Wanted’ columns. Immediately he was impressed and

elated by

the discovery that there were plenty of jobs, and that a satisfactory

percentage of them appeared to be big jobs … And so he decided the

wisest play

would be to insert an ad in the ‘Situations Wanted’ column, and then

from the

replies select those which most appealed to him.

“Writing

out an ad, he reviewed it

carefully, compared it with others that he saw upon the printed page,

made a

few changes, rewrote it, and then descended to the lobby, where he

called a cab

and was driven to the office of one of the great metropolitan morning

newspapers. Jimmy felt very important as he passed through the massive

doorway

into the great general offices of the newspaper … he was very sorry for

the

publishers of the newspaper that they did not know who it was who was

inserting

an ad in their Situations Wanted column.”

Jimmy

expected a hundred replies on the first day his ad ran, but four days

later,

after having received nary a single response, he was forced to start

answering

ads in the “Help Wanted” columns.

“What

leisure time he had he

devoted to what he now had come to consider as his life work—the

answering of

blind ads in the Help Wanted columns of one morning and one evening

paper—the

two mediums which seemed to carry the bulk of such advertising … He

soon

discovered that nine-tenths of the positions were filled before he

arrived.”

Finding

even that job hunting strategy futile, Jimmy stopped looking for jobs

through

the “Help Wanted” ads, and began taking a series of low paying jobs

just to

survive in Chicago. He eventually made friends with a street hoodlum

known as

“The Lizard.” When Jimmy turned down a handout from him, “The Lizard”

explained, “I’m taking it from an old crab who has more than he can

use, and

all of it he got by robbing people that didn’t have any to spare. He’s

a big

guy here. When anything big is doing the newspaper guys interview him,

and his

name is in all the lists of subscriptions to charity—when they’re going

to be

published in the papers.”

“Everything

was to be done to carry

the impression to the public through the newspapers, who were usually

well

represented at the training quarters, that Brophy was in the pink of

condition;

that he was training hard; that it was impossible to find men who could

stand

up to him on account of the terrific punishment he inflicted upon his

sparring

partners; and that the result of the fight was already a foregone

conclusion;

and then in the third round Young Brophy was to lie down and by

reclining

peacefully on his stomach for ten seconds make more money than several

years of

hard and conscientious work earnestly performed could ever net him. It

was all

very, very simple; but how easily public opinion might be changed

should one of

the sparring partners really make a good stand against Brophy in the

presence

of members of the newspaper fraternity!”

Jimmy,

however, grew tired of being Brophy’s punching bag. “And there before

the eyes

of half a dozen newspaper reporters, and before the eyes of his

horrified

manager and backer, Jimmy, at the end of ninety seconds, landed a punch

that

sent the flabby Mr. Brophy through the ropes and into dreamland.” Jimmy

then

endured another month of unemployment, during which he again tried

answering

“Help Wanted” ads. He came across one that read as follows:

“WANTED, an

Efficiency

Expert—Machine works wants man capable of thoroughly reorganizing large

business along modern lines, stopping leaks and systematizing every

activity.

Call International Machine Company, West Superior Street. Ask for Mr.

Compton.”

Jimmy

answered the ad and got the position, although he had to lie about his

past job

experience to get it. Eventually, he was framed for the murder of his

employer,

but The Lizard’s testimony in court cleared Jimmy of the charge. It was

another

newspaper story that made The Lizard come out of the shadows and

testify. He

told the court, “I been watchin’ the papers close, and I seen yesterday

that

there wasn’t much chance (for Jimmy), so here I am.”

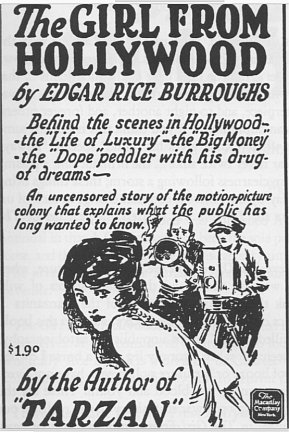

Burroughs

used newspaper articles to supply information and character connections

in The Girl From Hollywood, written in

1921-22. The author laid out the story’s contemporary plot in a

newspaper being

read by Colonel Pennington at his Ganado, California, ranch house.

“The

colonel was glancing over the

headlines of an afternoon paper that Eva had brought from the city.

‘What’s

new?’ asked Custer. ‘Same old rot,’ replied his father. ‘Murders,

divorces,

kidnappers, bootleggers, and they haven’t even the originality to make

them

interesting by evolving new methods. Oh, hold on—this isn’t so bad!

‘Two

hundred thousand dollars worth of stolen whisky landed on the coast,’

he read.

‘Prohibition enforcement agents, together with special agents from the

Treasury

Department, are working on a unique theory that may reveal the

whereabouts of

the fortune in bonded whisky stolen from a government warehouse in New

York a

year ago.’”

The

colonel went on to read aloud many other details in the article about

the

violation of the Volstead Act. The reader later learns that Guy Evans,

engaged

to the colonel’s daughter, was deeply involved in the sale of the

stolen

liquor. A separate story line brouight Shannon Burke into the mix. To

get

control of her, the dastardly director Wilson Crumb had furtively led

the

starry-eyed young woman into cocaine addiction in Hollywood. When her

mother, a

neighbor of the Penningtons, died, Shannon went to Ganado to take care

of her

mother’s affairs. Under the loving care of the Penningtons, Shannon

beat her

addiction and did not return to Crumb’s control. Back in Hollywood, the

young

woman Crumb found to take Shannon’s place just happened to be Grace

Evans, the

sister of Guy. Burroughs used another newspaper to explain how Crumb

worked his

evil on Grace.

“One

evening, toward the middle of

October, they were dining together at the Winter Garden. Crumb had

bought an

evening paper on the street, and was glancing through it as they sat

waiting

for their dinner to be served. Presently he looked up at the girl

seated

opposite him.

“‘Didn’t

you come from a little

jerk-water place up the line, called Ganado?’ he asked. She nodded

affirmatively. “‘Here’s a guy from there been sent up for

bootlegging—fellow by

the name of Pennington.’ She half closed her eyes, as if in pain. ‘I

know,’ she

said. ‘It has been in the newspapers for the last couple of weeks.’

“‘Did you

know him?’

“‘Yes—he

has been out to see me

since his arrest, and he called up once.’ A sudden light came into

Crumb’s eye.

“‘By God!’

he exclaimed, bringing

his fist down upon the table. ‘This fellow Pennington may not be

guilty, but I

know who is. It isn’t Pennington who ought to be in jail,’ he said.

‘It’s your

brother.’ And thus was fashioned the power he used to force her to his

will.”

Wilson

Crumb certainly needed killing for disturbing with the idyllic country

life of

the Penningtons, and he got it later when he brought his film crew to

Ganado.

Guy Evans did the good deed, but for a second time Custer Pennington

took the

rap. In a dual denunciation of the Los Angeles press and court system,

Burroughs announced the results of Custer’s trial.

“And so

there was no great surprise

when, several hours later, the jury returned a verdict in accordance

with the

public opinion of Los Angeles—where, owing to the fact that murder

juries are

not isolated, such cases are tried largely by the newspapers and the

public.

They found Custer Pennington, Jr., guilty of murder in the first

degree.”

There

is no indication of how the LA newspapers responded when Custer was

later

exonerated.

The

setting of ERB’s first Western novel, written in 1923, is the small

cattle-town

of Hendersville, Arizona, in 1886. Burroughs stocked the frontier

community

with simple needs, including a general store, a restaurant, a Chinese

laundry,

a blacksmith shop, a hotel, five saloons, and a newspaper office.

Rancher

Elias Henders was visiting the editor of the

Hendersville Tribune one evening, when they heard shouts and

gunshots

coming from the saloon across the street. “Boys will be boys,” the

editor

remarked. But when a bullet came through the office window, both men

ducked

behind the editor’s desk. The event led to Henders demoting Bull as

ranch

foreman and replacing him with the villainous Hal Colby.

Bull

is portrayed as a standard model quiet cowboy, but he had a cursory

habit

involving newspapers that would prove handy later in the story.

“Bull sat

in a corner of The

Chicago Saloon watching the play at the faro table. It was too early to

go to

bed and he was not a man who read much, nor cared to read, even had

there been

anything to read, where there was not. He had skimmed the latest

Eastern papers

that had come in on the stage and his reading was over until the next

shipment

of gold from the mine brought him again into contact with a newspaper.

Then he

would read the live stock market reports, glance over the headlines and

throw

the paper aside, satisfied. His literary requirements were few.”

It

was Bull’s knowledge of the current live stock market reports that

allowed him

to counsel Diana Henders when Maurice B. Corson, a shifty Eastern

lawyer, tried

to talk her into selling her ranch. “Mr. Corson is always telling me

that the

bottom has fallen out of the live stock business and that the new vein

in the

mine doesn’t exist,” the unsure Diana told Bull. He responded, “The

live stock

business is all right, Miss. It wasn’t never better, an’ as fer the new

vein

that’s all right too.”

Part One covers the topic in ERB's stories written from 1912 to 1923.

Part Two will address the newspaper theme in his works of fiction written from 1924 through 1940.

NOTE: Each title contains a hot link to my ERB Bibliography in ERBzine ~

Featuring cover & interior illustrations, publishing history, reviews, e-text edition, etc. for each edition

~ Bill Hillman

ALAN'S MANY

ERBzine APPEARANCES

www.erbzine.com/hanson

BILL HILLMAN

Visit our thousands of other sites at:

BILL and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® John Carter® Priness of Mars® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All Original Work ©1996-2025 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective owners