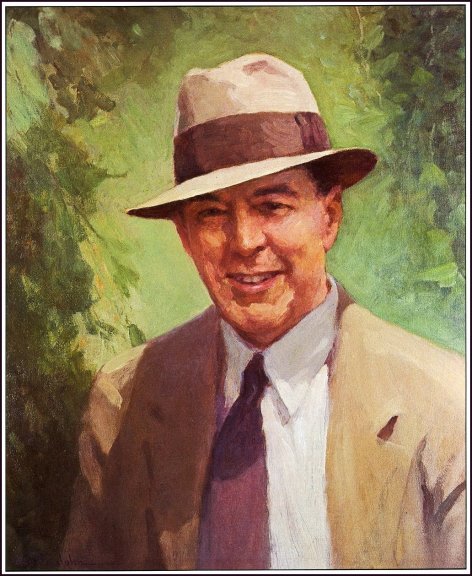

Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Volume 8080 |

ERB'S FORGOTTEN TALES

Introduction

by Patrick H. Adkins

by Patrick H. Adkins

“I have an idea that I am not a short story writer,” Edgar Rice Burroughs observed on July 26, 1919, in a letter to M.B. Gates of The People’s Home Journal; “but I also have a desire to become one in order to fill in between the longer stories, which are rather tiresome writing…”

This would seem to be an odd remark for a writer who had published a dozen short stories only two years earlier in Blue Book and recently had placed another half-dozen with Red Book–two of the top pulp magazines of their day–but those were Tarzan stories, for which there was always a ready market. The same was never true for Burroughs’ forays outside the jungle. As he would learn over the years to come, authors can become typecast just as surely as actors. A.H. Bittner expressed the editorial sentiment bluntly in 1930 when rejecting The Deputy Sheriff of Comanche County: “Our readers expect the Tarzan type of story from you and it certainly would disappoint a great many of them to hand them a western story under your name.”

Forgotten Tales of Love and Murder contains all of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ non-Tarzan short stories and fictional mystery puzzles. Of the nine short stories, only one has been previously published (not surprisingly, the only one with a fantastic theme). Their variety is impressive. With settings ranging from the old West to war-ravaged France, from Hollywood and Southern California to Hawaii and the South Pacific, they include social commentary, romantic comedy, and quiet tragedy–grisly murder, gruesome horror, and noble self-sacrifice. Together they constitute a virtual overview of Burroughs’ entire writing career, both stylistically and thematically, and through them all run the nearly universal themes of Burroughs’ fiction–love and violent death.

The stories are presented chronologically, beginning with “Jonathan’s Patience,” a playful, irreverent tale that predates Burroughs’ professional work by some seven years. (Even “Jonathan’s Patience,” to stretch a point for the sake of a title, turns out to be about love of a sort–the love of “luxury and assets.”) Bearing the ungainly title “Little Lessons for Little Learners–I. Jonathan’s Patience, or, How Fortune Came Through Faith (A Sunday School Story),” it was discovered among Burroughs’ papers by biographer Irwin Porges. At the request of Danton Burroughs, Robert R. Barrett compared the manuscript to other early Burroughs manuscripts and found that the handwritten title page, typewriter typeface, and peculiar style of paragraphing closely matched similar elements in the manuscript of Minidoka. “By taking all three of these into account,” Barrett concluded, “I think we can safely state that ‘Jonathan’s Patience’ was written either during or just after the writing of Minidoka–probably around 1904.”

Next comes “The Avenger,” a tale of brutal revenge apparently written while Burroughs was working on Tarzan of the Apes, a book with which it shares several stylistic and thematic elements, including the use of a formal introduction. (Although Burroughs dated this story 1912 in his notebook and it was submitted to The Associated Sunday Magazines on February 12, 1912, the exact date of composition is unknown.)

According to Burroughs’ writing notebook, “For the Fool’s Mother,” Burroughs’ first Western, was written October 3-5, 1912, during the period in which he was working on The Gods of Mars. “I have in mind a series of short stories, each complete in itself, with The Prospector as the principal character,” he explained to Donald Kenicott of the Story Press Corporation. Although it failed to interest a publisher, Burroughs liked the story well enough that in 1915 he used it as the basis of “The Prospector,” an unproduced screen scenario.

“The Little Door” (written November 17-23, 1917) presents Edgar Rice Burroughs at what may be the peak of his stylistic powers. Like The Land that Time Forgot and Tarzan the Untamed, it was written when anti-German sentiment in the United States was at its height during World War I. Burroughs’ patriotic fervor and righteous outrage ring in almost every word.

Burroughs wrote no short stories at all during the 1920s. When he finally returned to the form, he selected a locale and subject closer to home. Set among the hills of Los Angeles, “Calling All Cars” (June 12-14, 1931) is a clever tale of crime and romance in which nothing is as it seems. It is also the longest story in this volume.

“Elmer” (March 22-25, 1936), in which a defrosted caveman comes to Hollywood, was published in the February 20, 1937 issue of Argosy as “The Resurrection of Jimber Jaw” and has been reprinted several times. “I find that you like change,” Burroughs remarked to Argosy editor Jack Byrne on November 14, 1936, and that observation is amply borne out by a close comparison of “Elmer” and “Jimber-Jaw.” Not only did Argosy retitle the story and rename two characters, but hardly a paragraph escaped the editor’s blue pencil. While the Argosy version may read a bit more smoothly and adds an interesting layer of ambiguity to the happenings in Siberia, Burroughs’ original is a little gem just as he submitted it, and we are pleased to present his version here for the first time. (In an apparent case of self-censorship, Burroughs crossed out in pencil two sentences of Elmer’s dialogue concerning modern women: “They are only good for one thing; otherwise, they might as well be men. One does not need to take a mate for what they can give–not here where it is so easy to get.” For the pulp version, Byrne restored all but the last nine words. We have restored the entire passage.)

In “The Strange Adventure of Mr. Dinnwiddie” (July 16-17, 1940) Burroughs turned to comedy with an amusing misadventure that anticipated James Thurber’s 1947 “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” Like several others stories in this volume, it is noteworthy for its relative sexual candor. Perhaps trying to escape editorial typecasting, Burroughs submitted it for publication under the pseudonym John Tyler McCulloch, a name he had first used when trying to market “Pirate Blood” (another relatively “candid” work).

Burroughs’ foray into comedy continued with “Misogynists Preferred,” a lighthearted exploration of the Battle Between the Sexes. Written in Honolulu January 5-8, 1941, it too was submitted for publication under the McCulloch pseudonym.

“Uncle Bill” (May 19-20, 1944), the final short story in this volume, returns to more disturbing material with an unsettling tale drawn from everyday life. It is also the only story by Edgar Rice Burroughs told in the first person by a female narrator.

Although Burroughs kept meticulous notes about his fiction, carefully entering word lengths and dates of composition, he left few records concerning his fictional puzzles–which are not short stories, seem to have been written largely for his own amusement, and should be judged accordingly. As best we can tell, they were written in two or three batches–in early 1932, late 1935, and possibly mid 1940. Four of them were published in Rob Wagner’s Script Weekly, a small-circulation Beverly Hills magazine.

Of the puzzles, “The Red Necktie” is odd-man-out. It includes neither Inspector Muldoon nor a murder and employs the same basic idea as “The Bank Murder,” as if one were a rewrite of the other. The manuscript preserved in the files of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., does not include a solution; fortunately Flem Chapman was able to locate a copy of the solution as published in Script and provided it to us for inclusion here.

“Murder: A Collection of Short Murder Mystery Puzzles” introduces Police Inspector Muldoon, Burroughs’ last series character to appear in book form. The unnamed narrator who serves as Muldoon’s faithful Watson is clearly the fictional Edgar Rice Burroughs familiar to readers from so many of the author’s novels. (If you didn’t know that the fictional Burroughs played the violin, refer to the closing line of “Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fiction Writer: An Autobiographical Sketch,” which was originally published in Script as “Edgar Rice Burroughs Tells All.”)

There is a puzzle within these puzzles: “The Gang Murder,” said by Henry H. Heins to have been written November 6, 1935, is clearly set in June, 1940, although there is no indication why the chronicled events should take place in Burroughs’ future. To make matters more complicated, when Burroughs organized the collection he placed this puzzle ahead of “Murder at Midnight,” which Porges indicates was written November 5, 1935. What all this amounts to is that “The Gang Murder” seems to be out of sequence regardless of when it was written. Nevertheless, we present it here in the position indicated by Burroughs in the table of contents that accompanied his manuscripts.

The unfinished “The Dupuyster Case” (technically not part of “Murder: A Collection”) appears here as the final puzzle. Taking place September 17, 1932, it presumably was written at the same time as the earliest puzzles. Burroughs abandoned it with a note that it was “too long and too complicated,” but left an outline indicating the resolution, which we have also included.

Except as noted above, the texts presented in this book have been taken directly from Burroughs’ original manuscripts and prepared for publication as nearly as possible in accordance with the author’s expressed wishes. We have corrected occasional obvious errors and at times gently nudged the punctuation into conformity with the conventions of Burroughs’ time, but to preserve historical integrity we have not attempted to standardize spelling or usage throughout the volume. Instead we have treated each story or puzzle separately, so that, for instance, ain’t is spelled with an apostrophe in the mystery puzzles but without one in “For the Fool’s Mother” and “Calling All Cars.”

Here they are–eighteen nearly forgotten works by one of the most widely read authors of the Twentieth Century. Dated they may be (how could they be otherwise, written more than fifty years ago?), and certainly none of them is likely to alter Burroughs’ reputation as a writer. It’s probably true that the stories possess most of the strengths and weaknesses of Burroughs’ better known works. Still, those strengths remain impressive. By turns witty and sardonic, gripping, suspenseful, humorous, and horrifying, these long overlooked tales are above all else highly readable, boasting the authentic voice of a master storyteller. Their publication is long past due.

BILL HILLMAN

Visit our thousands of other sites at:

BILL and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® John Carter® Priness of Mars® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All Original Work ©1996-2025 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective owners