Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site for Over 20 Years Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webzines and Webpages In Archive Volume 5568 |

Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site for Over 20 Years Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webzines and Webpages In Archive Volume 5568 |

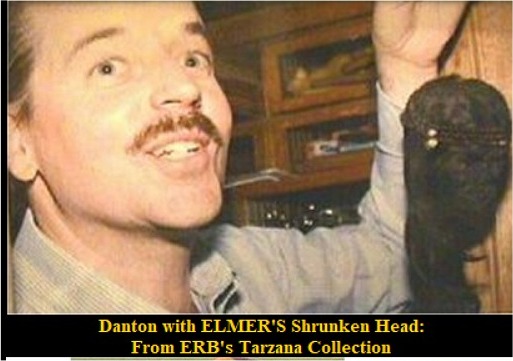

The name "Elmer" came from a human skull given to skull collectors Hulbert and Jack Burroughs by Ed's physician, Dr. Elmer Belt. The name was chosen in his honour. |

PART I: Chapters 1-3 After the third highball we were calling each other by our first names. By the sixth we had dragged the family skeletons out of their closets and were shaking the dust off of them. I had lost count by the time we were weeping on one another's shoulder. That was the first time we met.

1Anyhow, we got pretty well acquainted then. Afterward we saw a lot of each other when he brought his ship to the airport where I kept mine. His wife was dead, and he was a rather lonely figure evenings, so I used to have him up to the house for dinner often.

He had been pretty young when the war broke out, but he managed to get over just before the end. I think he brought down three enemy planes, although he was just a kid. I had that from another flyer; he never talked about it. But he was full of flying anecdotes about other war-time flyers and about his own stunting experiences -- he'd been a stunt pilot for the movies for several years.

None of which has anything to do with the story other than to explain how I became well enough acquainted with Pat Morgan to have it from him at all. There was really no reason why he shouldn't have told it, except that he seldom spoke of tragic occurrences -- his anecdotes were nearly all humorous. He always saw the humorous side of things.

We were lunching together at The Vendome the day that Stone's body was found. We saw the announcement in a screaming banner spread across the top of the front page of the Herald and Express.

2 I've always been inclined to putter around with inventions, and after my wife died I tried to forget my loneliness by centering my interest on my laboratory work. It was poor substitute for the companionship I had lost, but at that I guess it proved my salvation.I was working on a new fuel that was much cheaper and less bulky than gasoline, but I found that i required radical changes in engine design, and I lacked the capital to put my blue prints into metal.

About this time my grandmother died and left me a considerable fortune. Quite a slice of it went into experimental engines before I finally perfected, one. It was a honey.

I built a ship and installed my engine in it, then I tried to sell the patents on both engine and fuel to the Government, but something happened. When I reached a certain point I ran into an invisible stone wall -- I was stopped dead. I couldn't even get a permit to manufacture my engine.

I never did find out who or what stopped me, but I remembered the case of the Doble steam car. Perhaps you will recall that, also.

Then I got sore and commenced to play around with the Russians.

They were interested. They finally made me a splendid offer to fly my ship to Moscow and manufacture engines and fuel for them.

]

During the course of these negotiations I met Dr. Lord. He also was flirting with the Soviet government. Doubtless you recall reading about Lord's experiments with frozen dogs and monkeys. He used to freeze them up solid for days and weeks, and then thaw them out and bring them to life.The S.P.C.A. and the health authorities stopped him. So he was sore, too. We were a couple of soreheads, and I think we had a right to be; for we were both sincere in what we were attempting to accomplish -- he to fight disease, I to add something to the science of aviation.

The Reds welcomed him with open arms. They agreed not only to let him carry his experiments as far as he liked but to finance him as well. They even promised to let him use human beings as subjects and to furnish the subjects. They had a large stock of counter-revolutionists on hand.

When he found that I was going to fly my ship to Moscow, he asked if he might go with me. I told him the risk was too great, that I didn't want to take the responsibility; but he insisted, so I took him.

I won't bore you wit details of the flight. The engine functioned perfectly, so did the fuel, so did everything until we were flying over the most god-forsaken terrain anyone ever saw, in northern Siberia; then the carburetor went haywire.

We had about then thousand feet elevation at the time, but as far as I could see there seemed to be nothing but forests and rivers -- thousands of rivers.

I went into a straight glide with a tail-wind, figuring I could cover a lot more territory that way than by spiraling , and all the time I was looking for a spot, however small, where I might set her down without damage, for I guessed that we'd never get out of the endless forest unless we flew out.

I've always liked trees, but as I looked down on that vast host of silent sentinels of the wilderness, I felt the chill of fear and something that was akin to hate. There they stood -- in divisions, in army corps, in armies, waiting to seize us and hold us -- forever; hold our broken bodies; for when we struck them, they would cuss us, tear us to pieces.

Then a saw a little patch of yellow far ahead. It was no larger than the palm of my hand, but it was an open space -- a tiny sanctuary in the very heart of the enemy's vast encampment. As we approached it grew larger until at last it resolved itself into a few acres of reddish yellow soil devoid of trees. It was the most beautiful landscape I have ever seen.

As the ship rolled to a stop on fairly level ground, I turned and looked at Lord. He was lighting a cigarette. He paused, with the match still burning, and grinned at me. I knew then that he was regular. It's funny, but neither one of us had spoken since the motor quit. That was as it should have been; for there was nothing to say -- at least nothing that would have meant anything.

We got down and looked around. Beside us, a little river ran north to empty finally into the Arctic Ocean. Our tiny patch of salvation lay in a bend on the west side of the river. On the east side was a steep cliff that rose at least three hundred feet above the river . The lowest stratum looked like dirty glass. Above that were strata of conglomerate and sedimentary rock; and, topping all, the grim forest scowled down upon us menacingly.

"Funny looking rock," I commented, pointing toward the lowest stratum.

"Ice," said Lord. "My friend, you are looking at the remnants of the late, lamented glacial period that raised Hell with the passing of the Pleistocene. What are we going to use for food?"

"We got guns," I reminded him.

"Yes. It was very thoughtful of you to get permission to bering firearms and ammunition, but what are we going to shoot?"

"There must be something. What are all these trees for? They must have been put here for birds to sit on. In the meantime we've sandwiches and a couple of thermoses of hot coffee. I hope it's hot."

"So do I."

It wasn't.

I took a shotgun and hunted up river I got a hare and a brace of partridges. By the time I got back to camp the weather had become threatening. There was a storm north of us. We could see the lightning.

We had already wheeled the plane to the west and highest part of our clearing and staked it down as close under the shelter of the forest as we could.

By the time we had cooked and eaten our supper it commenced to rain. The long, northern twilight was obliterated by angry clouds that rolled low out of the north. Thunder bombarded us. Lightning laid down a barrage of fire about us.

We crawled into he cabin of the plane and spread our mattresses and blankets on the floor behind the seats.

It rained. And when I say it rained, I mean it rained. It could have given ancient Armenia seven and a half honor tricks and set it at least three, for what it took forty days and forty nights to do in ancient Armenia, it did in one night on that nameless river somewhere in Siberia.

I don't know how long I slept, but when I awoke it was raining not cats and dogs only, but the entire animal kingdom. I crawled out and looked through a window. The next flash of lightning sowed the river swirling within a few feet of the plane.

I woke lord up and called his attention to the precariousness of our situation.

"The Hell!" he said. "Wait 'til she floats", then he turned over and went to sleep again.

I lay awake most of what was left of the night. The water was a foot deep around the landing gear at the worst; then she commenced to go down.

The next morning the river was running in a new channel a few yards from the ship, and the cliff had receded at least fifty feet toward the east. The face of it had fallen into the river and been washed away. The lowest stratum was pure and gleaming ice.

I called Lord's attention to the topographical changes.

"That's interesting, " he said. "By any chance was there any partridge or hare left?"

There was, and we ate it. Then we got out and sloshed around in in the mud. I started to work on the carburetor. Lord looked at the havoc wrought by the storm.

He was down by the edge of the river looking at the new cliff face when he called to me excitedly. I had never before seen Lord exhibit any enthusiasm except when he was damning the S.P.C.A. and the health authorities.

I could see nothing to get excited about. "What's eating you?" I asked.

"Come here, you dumb Irishman, and see a man fifty-thousand years old, or thereabouts. "Lord was Irish only on his father's and mother's side.

I was worried. I thought maybe it might be the heat, but there wasn't any heat. No more could it have been the altitude, so I figured it must be hereditary, and crawled down and walked over to him.

"Look!" he said, and pointed across the river at the cliff.

I looked, and there, frozen into the solid ice, was a man. He was clothed in furs and had a mighty beard. He lay on his side with his head resting on one arm, as though he were asleep.

Lord was awe struck. He just stood there, goggle-eyed, staring at the corpse. Finally, he drew in his breath in a long sigh.

"Do you realize, Pat, that we are looking at a man who may have lived fifty-thousand years ago, a man of the Old Stone Age?"

"What a break for you," I said.

"Break for me? What do you mean?"

"You can thaw him out and bring him to life."

He looked at me in a sort of a blank way, as though he didn't comprehend what I was saying then he shook his head.

"I'm afraid he's been frozen too long," he said.

"Fifty-thousand years is quite a while, but wouldn't it be worth trying?"

3It took us two weeks to build a house of saplings and chink it with clay. It had a fireplace and a bench for Lord's paraphernalia that he'd brought along. Then it took us another two weeks to chip Elmer out of the ice We had to be careful, there was danger of breaking him.

We worked all around him, leaving him encased in a small block. Then we lowered him down to the ground, floated him across the river, and dragged him up to the laboratory on a crude sled we had built for the purpose.

All the time we were working on him we did a lot of thinking. What memories were locked in that frozen brain? What memories were locked in that frozen brain? What sights had those frozen eyes beheld in the days when the world was young? What loves, what hates had stirred that mighty breast?

He had lived in the days of the mammoth and the saber-tooth, and he had survived with only a stone spear and a stone knife until the cold of the great glacier had overtaken him.

Lord said he had been hunting and that he had been caught in a blizzard. Numb with cold, he had at last dropped down on the hard ice, succumbing to that inescapable urge to sleep that overtakes all freezing men; and for fifty-thousand years he had slept on, undisturbed. (god! how I envied him.)

Lord had the laboratory heated by a fire in the fireplace. The propellor of the plane, idling, kept the air in the room circulating, blowing wind through an opening that had been left in the wall for that purpose.

We kept turning Elmer over with first one side and then the other toward the fire until the coating of ice was all melted; then the body commenced to warm.

I knew perfectly well that the best we could expect was that in due time Elmer would turn blue and commence to smell, but for some reason I couldn't help being excited. Lord tried to be the cool and collected man-of-science, but he failed miserably. He was just as excited as I.

"What if he does come to life?" I asked. "have you thought of that, Doctor? Have you thought what it is going to mean to him to be fifty-thousand years away from his friends. Have you thought of what he may do to us? What sort of people were the men of the Old Stone Age? We may have named him Elmer, but he doesn't look the part. He looks as though he might have definite ideas about strangers who awaken people to whom they have not been introduced to people who have been peacefully sleeping for fifty-thousand years.

"Wilson, my friend, the gent may be sore."

"Do you think he'll come to life?"

"You ought to know; you're the doctor."

"Well, theoretically, he should; but --" Lord scratched his head, then he gave Elmer a blood transfusion, using me as the donor. After that, he injected adrenaline chloride solution into the belly.

When Elmer opened his mouth and yawned, Lord and I both stepped back as though we had been slapped in the face. I have never in my life felt such a weight of responsibility. I wished the man had stayed frozen or started to decay; but now that he had shown signs of life, we had to go on - it would have been murder not to. Think of murdering a man who was born fifty-thousand years ago!

Lord injected an ounce and a half of anterior pituitary fluid. Elmer scowled and wiggled his fingers. He was definitely alive. It frightened me. It was like messing around with business that belongs only to God.

Lord filled his hypodermic with posterior pituitary fluid and gave Elmer a shot of that.

The man of the Old Stone Age turned over and tried to sit up. Lord pushed him back gently and spoke soothingly to him; then he injected sex hormones from sheep.

For about two hours Elmer slept peacefully, and while he slept we stripped the soggy skin clothing from him and wrapped him in our own blankets from the ship.

He was a fine specimen of a man, about six-foot-one and beautifully muscled. Beneath his beard he appeared to have good and regular features, though perhaps a little heavy. Lord though he might be in his twenties. He certainly was not old.

After two hours, Elmer sat up and looked at us. A scowl darkened his face, and he looked about him quickly as though for his weapons. But they weren't' there. We had seen to that. He tried to get up, but he was too week.

He was a pretty sick boy for a long time. We both thought he'd never pull through. All the time, we nursed him like a baby and took care of him, and by the time he commenced to convalesce he seemed to have gained confidence in us. He no long scowled or shrank away or looked for his weapons when we came around, but smiled at us. And he had a mighty winning smile.

At firs he had been delirious and talked a lot -- in a strange tongue that we couldn't make head nor tail of. It was a soft, liquid tongue with the l's and vowels flowing through it; but low, like a deep river. There was one word that he repeated often in his delirium -- lilami. The way he said it sounded sometimes like a prayer and sometimes like a wail of anguish.

I had repaired the carburetor. There was really nothing the matter with it -- just clogged by a flake of foreign matter. We could have gone on at once, but there was Elmer! We couldn't leave him to die, and he was too sick to take along; so we stayed with him. We never even discussed the matter much -- just took it for granted that the responsibility was ours, and stuck along.

Lord was, of course, elated by the success of this first practical demonstration of the soundness of his theory; and I don't believe you could have dragged him away from Elmer with an ox team.

The fact that we couldn't talk with Elmer irked us. There were so many questions we wanted to ask him. Just think of it! Here was a man of the Old Stone Age who could have told us all about conditions in the Pleistocene, fifty-thousand years ago, perhaps, and we couldn't exchange a single thought with him. But we meant to cure that.

As soon as he was strong enough, we commenced to teach im English. At first it was aggravatingly slow work; but he proved an apt pupil , and as soon as he had a little foundation, he progressed rapidly. He had a marvelous memory. He never forgot anything -- once he had a thing, he had it.

No use reviewing the long weeks of his convalescence and education. He recovered fully, and he learned to speak English -- excellent English for Lord was a highly cultured man and a scholar. It was just as well that Elmer didn't learn his English from me -- barracks and hangars are not the places to acquire academic English.

If Elmer was a curiosity to us, imagine what we must have been to him. The little one room shack we had built and in which he had convalesced was an architectural marvel beyond the limits of his imagining. He told us that his people lived in caves; and he thought that this was a strange cave that we had found, until we explained that we had built it.

Our clothing intrigued him; our weapons were a never ending source of wonderment. The first time I took him hunting with me and shot game, he was astounded. Perhaps he was frightened by the noise and the smoke and the sudden death of the quarry, but if he were, he never let on. Elmer never showed fear, perhaps he never felt fear. Alone, armed only with a stone shod spear and a stone knife, he had been hunting the great red bear when the glacier had claimed him. He told us about tit.

"The day before you found me," he said, "I was hunting the great red bear. The wind blew; the snow and sleet drove against me. I could not see. I did not know in which direction I was going. I became very tired. I knew that if I lay down I should sleep and never awaken; but at last I could stand it no long and I lay down. If you had not come the next day, I should have died." How could we make him understand that his yesterday was fifty-thousand years ago?

Eventually we succeeded in a way, thought I doubt if he ever fully appreciated the tremendous lapse of time that had intervened since he started from his father's cave to hunt the great read bear.

When he first realized that he was a long way from that day and that it and his times could never be recalled, he voiced a single word -- lilami. It was almost a sob. I had never dreamed that so much heart-ache, so much longing could be encompassed by a single word.

I asked him what it meant.

He was a long time in answering. He seemed to be trying to control his emotions, which was unusual for Elmer. Ordinarily he appeared never to have emotions. One day he told me why. A great warrior never let his face betray anger, or pain, or sorrow. You will notice that he didn't mention fear. Sometimes I think he had never learned what fear is. Before a youth was admitted to the warrior class, he was tortured to make certain that he could control his emotions.

But to get back to lilami.

At last he spoke. "Lilami is a girl -- was a girl. She was to have been my mate when I came back with the head of the great red bear. Where is she now, Pat Morgan?"

There was a question! If we hadn't discovered Elmer and thawed him out. Lilami wouldn't have been even a memory. "Try not to think about her, old man," I said. "You'll never see Lilami again -- not in this world."

"Yes, I will," he replied. "If I am not dead, Lilami is not dead. I shall find her."

A popular item in the Burroughs Family Tarzana Memorabilia is

a shrunken head that Ed Burroughs named Elmer