Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages in Archive

Volume 6726

UNCLE BILL

A horror story unpublished in the author's lifetime

By Edgar Rice Burroughs

In 1944 Burroughs devised realistic background elements for a horror story. In "Uncle Bill," a brief 1,787-word narrative written in only two days, May 19 to 20, Ed chose a "Young Woman named Mary" to summarize the one event in Aunt Phoebe's life.

Aunt Phoebe was, I think, the most remarkable woman and the sweetest character I have ever known, IN the little New England town where she was born in 1847 and where she died eighty-seven years later, she was worshipped for her good deeds and revered for her probity. "The finest woman that ever lived," was the unanimous appraisal of her fellow townsmen. All their lives they had come to her with their sorrows and their joys, many of them and when those who didn't come were in trouble Aunt Phoebe would go to them.She was beautiful, too, in a way, even up to the day of her death. For she was still slender and active and alert, nor had time succeeded in entirely erasing the beauty of her youth. That, I am sure, was due to Uncle Bill.

They had married in 1863, when Aunt Phoebe was sixteen and Uncle Bill twenty-one. He was a second lieutenant in the Army of the Potomac. Their brief honeymoon was spent in the two-story and attic clapboard house that was a wedding present from Aunt Phoebe's father. I spent the first fifteen years of my life there, and I used to love it. It just oozed historic memories, for it had been built in 1770; and heaven only knows how many great men "slept" there. When I was a little girl, people used to come especially to see its "Connecticut Valley" doorway. And I imagine that they still did up to the time it burned down last month.

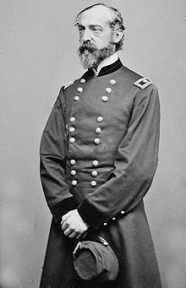

When Lee surrendered at Appomattox, April 9, 1865, Uncle Bill was a captain on General Mead's staff. He ws given a six months leave of absence about a year later, and came home to spend it with Aunt Phoebe in -- let's call it Wesford. There is an excellent reason for not identifying either the town or myself accurately.

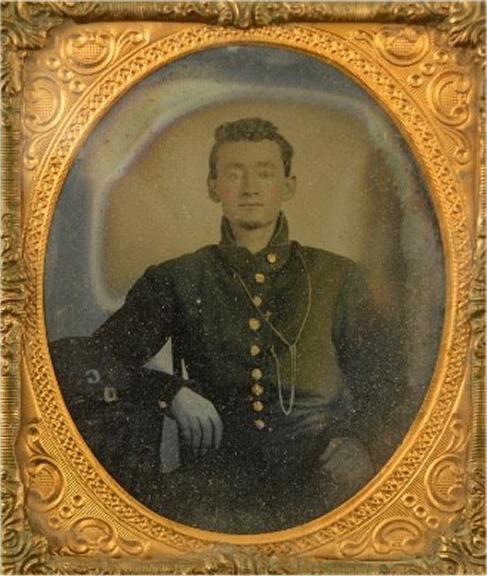

Uncle Bill was a dashing figure in his captain's uniform, fitly supplementing the beauty of his young wife. There were many daguerreotypes of Uncle Bill alone and with Aunt Phoebe in the faded family album and in Aunt Phoebe's bedroom, and a life-size oil of Uncle Bill hung in the parlor. In fact, you could scarcely go anywhere in the house without seeing Uncle Bill. You just felt that he might walk in any moment, although he hadn't for the sixty-eight years preceding Aunt Phoebe's death.

He stared for Boston in 1866, Aunt Phoebe recalled, on a beautiful September day. She herself had driven him the four miles to the station through the elm-shaded streets of Wesford and then along the winding country road flanked by the deep wine-coloured velvet of sumach.

And Aunt Phoebe was always expecting him to return. That is what kept her young. "I don't want your Uncle Bill to come back to an old woman," she used to say. For sixty-eight years a light burned every night and all night in the reception hall behind the "Connecticut Valley" doorway, so that if Uncle Bill should come back after dark he wouldn't have to grope his way about blindly.

Bob and I came to live with Aunt Phoebe in 1919. Bob is my brother. He was one year old and I just a few weeks. Our mother had died shortly after I was born, and father before I was born. He was killed in France just before the armistice. Aunt Phoebe and Mother were half sisters. There was thirty-one years difference in their ages, but I am sure that there was not that much difference in their outlook on life and their reactions to the times in which they lived, for though Aunt Phoebe was seventy-two years older than I, she never seemed like an old woman to me. That was the influence of Uncle Bill, I guess. He wasn't there in the house, but he was always very much alive to all of us.

Aunt Phoebe spoke of him often. She kept him alive for herself and for us. And perhaps he was alive for all we knew. So Bob and I as we grew older just took it for granted that he might come home at any minute. We always thought of him as a young man in his captain's uniform -- just as he had looked when Aunt Phoebe drove him to the station long years before -- just as he looked in the pictures in the family album and in the big oil painting in the parlor.

Wesford lies well off the main highway, a quiet and restful town that has changed but little in a hundred years. Victorias and runabouts have long since given way to Fords and Packards and Cadillacs, and stables have become garages, but the old homes are there and many of the old families, and the town drowses beneath the same old elms that shaded their forebears.

Wesford had grown old gracefully, and Aunt Phoebe had remained young gracefully, She had passed from tallow dips to kerosene to gas to electricity quite as though she had always been expecting each innovation. Without regret, she had put her horses out to pasture and bought the first horseless carriage to disrupt the somnolence of Wesford. She had been among the first to install a telephone in a home and to own a radio. She did nothing ostentatiously. She merely lived in the present, accepting those things which were of the present. She never lived in the past. Even Uncle Bill seemed of the present to her, as he did to us and to Aunt Phoebe's friends and servants.

Jim Hecker, the gardener, who used to come in by day and who was almost as old as Aunt Phoebe, used to say to her, "Well, it's about time Cap'n Bill was comin' home, Miss Phoebe," and she'd say, "Yes, Jim, I'm expecting him most any day now." And Maggie, the housekeeper, turned down Uncle Bill's bed and laid out his long nightgown and slippers every night, just as she had for the twenty years she had been with Aunt Phoebe.

The chauffeur and the parlor maid were young, and I think they were a trifle skeptical about the chances of Uncle Bill returning after so many years. But Cook, who had been with Aunt Phoebe even long than had Maggie, apparently expected every morning that Uncle Bill would come down for breakfast.

It was in this atmosphere of pleasurable expectancy that Bob and I spent a happy childhood in Wesford. ONce a year, during the Easter vacation, Aunt Phoebe took us to Boston. As Bob and I grew older we used to think that she made these trips in the hope of finding Uncle Bill, and he and I were always looking for a dashing young captain in uniform. We couldn't visualize Uncle Bill any other way.

The woods around Wesford are always lively. It is difficult to determine when they are the loveliest. In May they are pink and white with mountain laurel. It was then, on Saturdays and Sundays, that Bob and I wandered through them hunting for birds' eggs. And in June, after school had closed, we picnicked in them with our friends among red and white azaleas. No two children ever had a happier childhood, for no other children had Aunt Phoebe. She was both mother and sister to us, going into the woods with us to find birds' nests, picnicking with us and our friends.

How suddenly it all changed one day in 1934, ten years ago. Aunt Phoebe is dead. Bob is somewhere in the South Pacific commanding a heavy bombardment group. I live in Boston with my little boy, awaiting the return of my husband, a West Point classmate of Bob, who is with the Army in Italy. And the old house in Wesford has burned down. An it was Uncle Bill who caused the sudden change.

Aunt Phoebe had had to go to Boston on business. It was the firs time she had ever gone without us, and we missed her. It was a gloomy, rainy day that kept us indoors. Tired of playing games or reading, we wandered about disconsolately. On the second floor, at the back of the house, were the servants' quarters -- all but the chauffeur, who had a room over the garage. Maggie and the parlor maid were out for the afternoon, and Cook was down in the kitchen. No one was upstairs ass Bob and I went to the storeroom next to Maggie's room to see what we could find to amuse ourselves.

Rob's eyes fell upon the padlocked door to the attic. When we had been younger, we had wanted to explore the attic; but Aunt Phoebe had explained that it held memories of the past that she didn't wish to be reminded of. "Just things," she had said, "that are of no use to anyone any more." But she had never forbidden our going up to the attic. The heavy, old-fashioned padlock had accomplished that.

Bob was sixteen then, and I fifteen. He had been reading the life of Houdini, and that padlock challenged him. "I can open that thing," he said.

"But Aunt Phoebe wouldn't like it," I countered.

"She never said we shouldn't. And anyway, I won't hurt the lock any; and I'll lock it up again."

Nevertheless, my conscience troubled me as Bob tinkered with the lock. I hoped that he wouldn't be able to open it. But he did open it. It was foolishly simple. Bob was quite proud.

We looked up the dusty stairway into the gloom above. "Let's go up and take a peek," said Bob.

"We shouldn't."

"Oh, what harm will it do? Come on!"

If you have ever been a little girl with an older brother whom you adored, you will know what I did. I followed Bob up those creaking stairs. But what a disappointment rewarded us. The attic was absolutely empty except for an old trunk which stood in the centre. It was tied 'round with rope and covered with dust. Cobwebs depended from the rafters. Dust an cobwebs covered the two little windows which let in the faint light that relieved the gloom.

"I wonder what's in that trunk,' wondered Bob. "Maybe old postage stamps on old, old letters -- stamps are sometimes worth thousands of dollars you know."

"Oh, please don't," I begged. "Aunt Phoebe wouldn't like it." But I helped Bob unwind the rope from around the trunk and watched him as he worked with the ancient lock.

"There!" he exclaimed as success crowned his efforts and he threw back the lid.

I screamed. Bob shrank back, his face white as a sheet. In the trunk was the mummified corpse of a man, clad in the Civil War uniform of a captain. There was a round hole in the skull between the eyes -- a bullet hole.

With trembling hands Bob lowered the lid. He put an arm about me and helped me down the stairs. I was afraid that I was going to faint.

At the foot of the stairs stood Aunt Phoebe. Her face was livid pale. "What were you doing up there?" she demanded. It didn't sound like Aunt Phoebe's voice. "What did you find?"

"Uncle Bill," said Bob.

She turned away and went to her room. She did not come to dinner that night. She did not come to breakfast the next morning. When Maggie and the chauffeur broke down the door, Aunt Phoebe was dead. A half empty box of sleeping tablets lay on the table beside her bed.

REVIEW AND SUMMARY FROM PORGES In "Uncle Bill," Mary and her brother Bob, their parents dead, had come to live with Aunt Phoebe in 1919. Staying with her in the two story and attic clapboard house in the little New England town of Wesford, they became aware of the all-pervading presence of Uncle Bill, who had disappeared many years before. Following Lee's surrender in 1865, Uncle Bill, a captain on General Meade's staff, had obtained a leave of absence and returned home. Aunt Phoebe recalled how, at the end of his leave, she had driven him to the station, and Mary describes her Aunt's unfailing belief that Bill would come back: "That is what kept her young. I don't want your Uncle Bill to come back to an old woman, she used to say. For sixty-eight years a light burned every night and all night in the reception hall. . . so that if Uncle Bill should come back after dark he wouldn't have to grope his way about blindly."Growing up in these surroundings, with Aunt Phoebe speaking of Bill constantly, Mary and Bob "just took it for granted that he might come home at any minute." But in telling the story, Mary describes the terrible change that had occurred "one day in 1934, ten years ago." With Aunt Phoebe away in Boston on business, Mary and Bob, then fifteen and sixteen, entered the attic, where they had never been before. Curious, Bob untied the rope around a large trunk, forced the lock, and flung the lid back. "In the trunk was the mummified corpse of a man, clad in the Civil War uniform of a captain. There was a round hole in the skull between the eyes — a bullet hole."

Aunt Phoebe, returning at that moment, stood at the foot of the stairs. When she asked in a strange voice, "What did you find?", Bob answered, "Uncle Bill." The next morning Aunt Phoebe was found dead, a half-empty box of sleeping tablets near her bed.Despite some successful touches of realism, the story becomes merely a horror incident, the ending anticipated as soon as Bob and Mary discuss the attic. The viewpoint adopted by Burroughs, with Mary, the narrator, merely summarizing events, destroys the necessary suspense and of course weakens the characterization. Aunt Phoebe does not receive the individual development needed to explain her actions, and since the relationship between her and Uncle Bill is never established, the reader can conceive of no reason for the murder. Sent to the Saturday Evening Post and Liberty in August-September 1944, and to Cosmopolitan in November, "Uncle Bill" was rejected by all three.

~ Porges P. 1294

Read Two ERB unique interpretations of "Uncle Bill"

by ERB Researchers Doug Denby and John Martin at

www.ERBzine.com/mag67/6726a.html

See Part II of Doug Denby's Thoughts on "Uncle Bill"

at

http://www.ERBzine.com/mag67/6726b.html

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

All

ERB Images© and Tarzan® are Copyright ERB, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work © 1996-2019/2020 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.