Volume 1809a

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/balaoo2.htm

| Book the Second

Balaoo has the Time of his Life. |

|

| Chapter I. | There are Limits to Balaoo's Patience |

| Chapter II. | The Tsarina's Dress |

| Chapter III. | "There are Men who Behave Worse than Savages" |

| Chapter IV. | Balaoo Dares not Come Home |

| Chapter V. | The Siege of the Forest |

| Chapter VI. | Hubert, Siméon and Élie |

| Chapter VII. | The Attack |

| Chapter VIII. | Balaoo Defends Himself |

Not to mention that he had lost his hat. This careless attire and the job which he had just pulled off at Riom led him to avoid the high-road and to look askance upon the passers-by. He sat.down quietly in the middle of a thicket and leant against the trunk of a beech to put on his boots, which he usually took off when he was going through the forest and sure of not meeting any of the Race.

The fact was that he had been taught never to attract attention either by his get-up or by his wild-man's gestures. Since he had had explained to him what a pithecanthrope (6) was, he accentuated the gentleness and shyness of his manners, for he wished on no account to be confused with a member of the monkey race, who are so rude and ill-bred. It was quite bad enough to be taken, because of his almond eyes, his slightly flattened nose and his face with the broad flat surfaces, for a native of Hal-Nan, whom Dr. Coriolis, who had been French consul at Batavia, had brought back from his travels and taken into his service as his gardener.

So Balaoo put on his boots. As he found some difficulty in forcing in his hind-hands --- for Balaoo could say what he liked: pithecanthrope though he was, he had more of the monkey than the man about him, since he had four hands, which is the obvious characteristic of the quadrumana --- he heaved slight sighs, in other words, he gave forth growls which the inhabitants of Saint-Martin-des-Bois had more than once taken for the premonitory sounds of a storm.

Moreover, it was one of his favourite amusements to imitate the thunder with his reverberating, rolling voice, when far away from men, to frighten them. He distinctly remembered seeing his father and mother filling the whole family --- his little brothers, his little sisters, his old aunt and him, Balaoo --- with unspeakable delight by striking their chests, down yonder, in the heart of the Forest of Bandong, not so very far from the bamboo villages built hanging over the swamps. They thumped their chests like men-singers about to raise their voice; and they brought forth the thunder. Oh, it was quick work! Hidden behind the mangroves, they at once saw the bravest members of the Human Race, even the very Dyaks, who are armed with bows and arrows, run like water-rats in search of a shelter, of a well-fortified kampong, behind which they heard them call upon Patti Palang Kaing, the king of the animals, himself. What fun they had in those days! Balaoo had his boots on. He reflected that, now, when he mimicked the voice of the thunder, he was scolded on returning home. And there was cause for it, no doubt; for, after all, he ran the risk that, one fine day, it would be discovered that the thunder was he! And his master had told him flatly that he would not answer for the consequences. The members of the Human Race, if they found Balaoo out, would treat him like a gorilla or a common gibbon. He would be popped into a cage . . . and a good job too! He had better bear that in mind.

What he had in mind at the moment was the stroke of work which he had done at Riom. And, when, by the last glimmer of daylight, he saw two gendarmes pass along the road, the short hairs on the top of his head stood up and began to move swiftly to and fro, an unmistakable sign of terror . . . or of rage.

He considered that the gendarmes did not go away quick enough. He was late: he had been away two days. He wished himself home again. What would his master and Mlle. Madeleine say? He could hear their reproaches now: they had had to look for him, to call after him in the forest. All the same, before he went in, he must go and tell Zoé of the stroke of work which he had done at Riom.

The road was free. He crossed it at a bound and ran across the fields to the cabin of the Three Brothers Vautrin.

It stood midway between the forest and the village, all by itself, on the roadside, with a screen of poplars behind it. It consisted of but one floor, covered with a thatched roof, from which rose a single chimney sending its smoke straight up into the peaceful evening. There was no light at the window. When he opened the door, a figure sitting huddled in the chimney-corner asked:

"Who's there?" He replied:

"It's I, Noël."

Balaoo's voice was both dull and guttural, rasping out the syllables low down in the throat. Bottles and bottles of syrup had been used up in the effort to "humanize" that voice. It was a little painful, a little startling, but not unpleasant to listen to. And, even with that voice, as he possessed the genius of mimicry, he managed to imitate a number of other voices and to excite sympathy for an incurable sore throat. When he tried to soften it, when speaking to young ladies, it produced a queer piping sound which roused laughter; and he hated that. He went about saying that he owed that curious lack of control over his vocal organs to the excessive use of betel in his youth; but, of course, he had given up chewing since he entered the service of his kind master, Dr. Coriolis!

"It's I, Noël."

The figure in the chimney-corner rose and another dark figure, in a recess in the wall, sat up on end. Mother Vautrin, the old paralyzed woman, and little Zoé looked at him with questioning eyes.

Zoé struck a match. Balaoo knocked it out of her hand and put his foot on the burning wood. He said there were gendarmes on the road and he did not want to be seen in the cabin. The old mother moaned in her dark corner; and the breath rattled in her throat, for she was very ill; but the first words uttered by Balaoo gave her relief:

"They will be here, in a cart, at eleven o'clock tonight . . . Have everything ready . . . "

Zoé was on her knees, kissing the pithecanthrope's boots:

"Have you saved them, Noël? .. . Have you seen them? . . . Are they coming, all three of them?"

And she named them, to make sure that not one would be missing: "Siméon? Élie? Hubert?"

Balaoo growled:

"Yes, Siméon, Élie and Hubert!"

"You've done it, Noël, you've done it?"

She continued to drag herself at his feet, but he pushed her away with his heel. The girl irritated him: when brothers were at liberty, she was always complaining about being beaten; and, now that she heard that they had been rescued from prison, she was licking his boots for joy.

"Quick!" he said. "Let me get back. What will they say to me at home?"

The child burst into tears:

"Mlle. Madeleine has been looking for you all day. She went all over the forest calling out, 'Balaoo! . . . Balaoo! . . . Balaoo! . . . "

"Oh, bad luck!" said Balaoo, giving himself a great blow, on the chest, which resounded like a gong.

And he left without even taking leave of the old woman, so great was his hurry to get away.

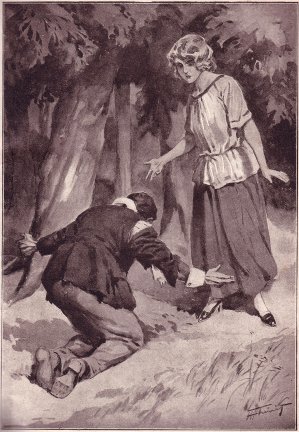

Once outside, he sniffed the air. It no longer smelt of gendarmes. He went through the vineyard, by a path which he knew well, from taking it a hundred times when he had leapt his master's wall to fetch the Vautrins and go with them in search of adventures or to have "a rare old spree" in the forest. And he at once reached the back of the Coriolis estate, by the little door opening on the woods. He carefully sniffed the path leading to the station, but it did not smell of railway-passengers. Then, trembling, he gave a tug at the bell. It tinkled so loudly that Balaoo almost fainted.

Footsteps creaked upon the dead leaves on the other side of the wall. Balaoo fell on his knees upon the stone threshold. The door opened and Balaoo at once felt a hand seize him by the ear.

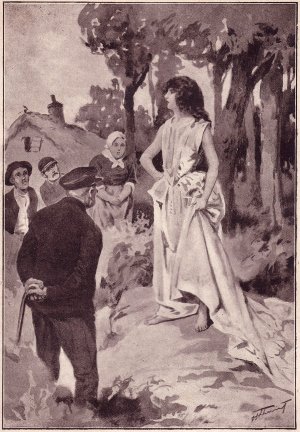

"You rascal!" said an angry young female voice. "I'll make you pay for this! . . . Two days and two nights out of doors . . . and in such a plight! . . . A nice thing! . . . I could cry, to look at you! . . . I have cried, Balaoo, I have cried! . . . Oh, don't you go crying, you; don't you begin! You'll bring the whole village round you! . . . You young scamp, you! . . . All your clothes in rags! . . . Your new trousers! . . . Your Paris overcoat! . . . You've been climbing the trees, sir, you've been larking in the moonlight! . . . And you've upset papa most terribly! . . . "

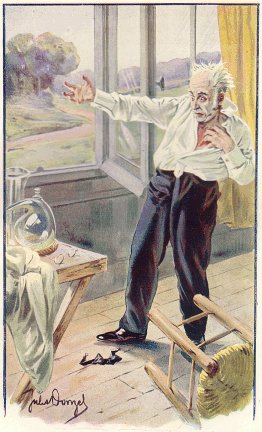

Dragged by the ear, docile, repentant, snivelling and with his heart throbbing loudly with remorse, Balaoo let the girl lead him to his quarters. But, on reaching the end of the kitchen-garden, where he was supposed to work with M. Coriolis, in the greatest mystery, at the different transformations of the bread-plant, and opening the door of his room, he found himself in the presence of Coriolis himself. He at once made a movement as though to return to the friendly forest at a bound.

Coriolis' face was colder, deader than marble.

Balaoo knew that expression. He dreaded nothing on earth so much as the sight of it. He would have preferred beatings and even the whippings with which he was tamed in his early youth to the silent reproach of those fixed eyes, of the haughty and contemptuous mask assumed by one of the Human Race who had obviously made a mistake in thinking that there was anything to be made out of a mere pithecanthrope.

And Coriolis' lips --- if they moved at all, for there were days when they remained closed as though human speech would be disgraced by conversing with a pithecanthrope --- Coriolis' lips were perhaps about to ask him, in front of Mlle. Madeleine --- oh, the shame of it! --- how his friends were, the great wild-boar of the Crau-mort and the wild-sow, his good lady, and the little wild boars, their children; and had he brought a message from the family of wolves that lived on the table-rock of Madon ? Oh, horror! He who used to visit the brothers Vautrin, before they went to prison! And who was treated by them as an equal, as one of the same race! And even that he must not say, of course, because his master had remarked to him, one day, after meeting him on the road with his three chums, that he would rather have seen him in the company of hyenas, and jackals! So that he no longer knew where he was! After all, they belonged to the Human Race, they did! . . . '

Coriolis moved his lips:

"Turn round!"

Balaoo did not obey.

But Balaoo did as though he had not heard. He knew that his overcoat was nothing more than a rag and that the seat of his trousers was hanging down behind. He could never display such a sight before Mlle. Madeleine.

Coriolis took a step towards Balaoo, who began to tremble in every limb. Madeleine interposed with her gentle voice, with her gentle face of entreaty. She had understood Balaoo's shame. She wanted to spare him the disgrace. His eyes filled with tears. Oh, he loved her, he loved her, he loved her! Goodness, how he loved her! . . .

But the doctor commanded:

"I want him to turn around!"

Then the soft voice said:

"Turn round, Balaoo dear!"

Ah! "Balaoo dear!" She could do what she pleased with him, when she dropped his man-name and called him by that which his father and mother had bestowed upon him in the Forest of Bandong: Balaoo! . . .

Balaoo dug his toe-nails into the soles of his boots and turned round.

Then a laugh which he had never heard before echoed through the room.

He spun round furiously. There stood a man whom he recognized at once from meeting him sometimes in the village street. He was the friend of the man who limped and whom he, Balaoo, could not stand at any price, the friend of that M. Bombarda whom he smacked in the face whenever the opportunity offered. He was the friend also of the gendarmes who had taken the Three Brothers to prison. Had he come to take Balaoo to prison too? What was he doing here? . . .

It was the first time that Balaoo had had the honour of having a stranger brought to see him! It was the first time that he was receiving a guest under his roof, that people condescended to introduce one of the Race to him in his own apartments!

By Patti Palang Kaing, his king, his god, the man had laughed at the condition of the pithecanthrope's trousers! But Balaoo spun round so quickly and so furiously that the man's laughter broke off in the middle and the man himself, terror-stricken, rushed to take refuge behind the table.

"Don't be afraid, monsieur," said Coriolis. "He's not dangerous. He wouldn't hurt a fly!"

"A fly!" growled Balaoo, within himself. "A fly indeed! Better ask Camus, the tailor in the Cours National, who was always making fun of me, better ask him if I wouldn't hurt a fly!"

"Come here, Noël," said Coriolis.

And, as Balaoo came forward, quivering with anger, Coriolis, with his grand white beard, resuming his kinder manner, gave the pithecanthrope a friendly little tap on his raging cheek. Balaoo drew in his dog-teeth and wiped his forehead with his handkerchief. It was high time. Another minute and the stranger would have taken him for a brute.

The visitor said:

"It's extraordinary! I have seen monkeys at the music-hall, but anything to equal this . . . never! "

Balaoo clenched his fists to his mouth to prevent the thunder that swelled his chest from bursting.

Coriolis said:

"Never use that word in his presence."

"What word?"

"Monkey."

"Oh, does he understand as much as that?"

"You need not ask if he understands: look at the face he's pulling!"

"Yes, he frightens me," declared the visitor, stepping back in alarm.

"Once again, you have nothing to be afraid of. You have vexed him by using that word, but he wouldn't hurt a fly . . . "

"Oh, he understands anything!" continued Coriolis.

"And you say that he speaks?"

"He speaks better French than our peasants. Speak, Balaoo, say something." Balaoo, seeing himself treated, in front of one of the Race, like an interesting animal at a fair, turned his poor face, wrung with shame and despair, to her who always, at his worst trials, had been his supreme consolation and who sometimes, when his brain relapsed into animal darkness, had proved herself his saving star.

Madeleine, seeing his anguish, gave him a smile and uttered these words:

"Book of etiquette, paragraph ten."

The pithecanthrope at once turned to the visitor:

"I have not had the honour of being introduced to you, monsieur," he said, in a roar that made the house shake again.

"Oh!" exclaimed the visitor. "Oh! Ah! Ah!..."

And he opened, the wide eyes of one who is ready to rush away in fright.

But Coriolis was not satisfied:

"Politely," he said. "Politely. In your gentlest voice."

"Come, Balaoo, in your gentlest voice," insisted Madeleine, in her own gentle voice.

And Balaoo repeated the sentence --- "I have not had the honour of being introduced to you, monsieur" --- in the piping voice that made all the young ladies laugh, excepting Madeleine.

"But it's marvellous," shouted the other member of the Race. "It's marvellous, marvellous! . . . I can't believe it! . . . He can't be a pithecanthrope! . . . "

"He's not one any longer," Coriolis assented. "He's a man."

At these words, Balaoo raised a proud and triumphant forehead.

Coriolis proceeded to make the introductions in the terms prescribed in the book of etiquette:

"I have the honour to introduce to you M. Noël, my valued assistant in my work on the bread-plant." And, turning to Balaoo, "This, my dear friend, is M. Herment de Meyrentin, the examining-magistrate, who is very anxious to make your acquaintance. Pray sit down, gentlemen."

The "gentlemen" sat down.

"You know what a magistrate is, my dear Noël?" asked Coriolis, with an important air.

"A magistrate," replied Balaoo, with an air of equal importance, "is a man who sends thieves to prison."

"And what is a thief?" M. de Meyrentin ventured to ask.

"A thief," said Balaoo, imperturbably. "is a man who takes things without paying for them."

And he closed his eyes to escape the visitor's curious scrutiny:

"That magistrate's a great bore," he thought. "Is he never going?"

"May I give you some tea?" said Madeleine, in her musical voice.

Tea! Balaoo, utterly dazed, opened his eyes again. Madeleine handed him a cup and he stirred the sugar in the fragrant brew with the tip of his silver-gilt spoon.

Only, just before drinking, believing that no one was looking at him, he swiftly dipped his hand into the liquid and sucked his fingers, pithecanthrope-fashion. That was a thing he could not resist.

Coriolis and M. de Meyrentin, who were carrying on an eager conversation between themselves, did not notice the ill-bred action; but Madeleine saw it all and silently scolded Balaoo with a threatening forefinger. Balaoo glanced at her out of the corner of his eye and gave a sly grin. Then, when Coriolis looked at him again, he drank like a man and put his cup down prettily on the tray.

Next, Balaoo crossed his legs, swung one foot with a careless grace, threw himself back in his chair with a smirk and sat smiling fatously. Suddenly, M. Herment de Meyrentin stooped, took Balaoo's right hand and examined it attentively:

"But these are not the hands of a . . . "

Coriolis cut him short: "Hush," he said. "I warned you not to use that word . . . and I have already told you of the work to which I have devoted myself for the last ten years. You can do anything with electrolytic, depilatory creams and a little patience. Look at his face: wouldn't you say he was a Chinese or a Japanese, just a trifle sunburnt? Who would ever take him for a quadrumane? You can use that word: he does not understand it."

"A quadrumane? A quadrumane?" repeated Herment de Meyrentin, rather irritably. "I've seen only two hands so far . . . "

"Balaoo, take off your boots." Balaoo thought that his ears must have deceived him. But no, Coriolis repeated the hideous command. Take off his boots! He, who has always been forbidden to show his shoe-hands! And who had been brought up to loathe and abominate his lower extremities! And who had never revealed this mystery except before the brothers Vautrin, in the depths of the forest, on days when he had gone hunting without leave and taught them to build invisible little huts in the trees! . . .

No, then, no, he would not take off his boots! The disgrace was too great, when all was said! And he stood up, with his hands in his pockets, whistling a tune, as though he had forgotten all about it. To his surprise, the others said nothing. They watched him as he walked, for Balaoo was walking up and down, with a thoughtful brow, as we sometimes do when we have something that preoccupies our mind. He forgot that he had no seat to his trousers. A scrap of conversation between his two visitors reminded him of it:

"You see, he has no appendage like that which we see in the lower quadrumana: no tail and no callosities. Note also that the bones of the ischium, which forms the solid framework of the surface on which the body rests when sitting, are less developed than in the quadrumana endowed with ischial callosities and are shaped more like those of a man. Lastly, he walks, as a rule, slowly and circumspectly; and I have taught him to give up his habit of waddling . . . "

Just then, in his annoyance, Balaoo began to waddle from side to side.

"You'd better waddle!" cried Coriolis, angrily. "I'll send you waddling in the streets of the village; and the school-children will laugh at you, Balaoo!"

Balaoo thought to himself :

"Ask Camus and Lombard, who were found hanged, why I put them to waddle at the end of a rope!" (7) But Balaoo's trials were not over. After taking off Balaoo's boots himself, Coriolis took his shoe-hands in his own, human hands. Balaoo turned away his head so as not to witness a sight that, disgusted him. But he could not help hearing.

"You see," said Coriolis, "that the great toe of the foot, which is smaller than in a man, makes up for this by being much more flexible."

"I hope he's not going to tickle me!" thought Balaoo.

M. Herment de Meyrentin nearly swooned with delight, when he saw, at last, the feet of the man who walked upside down.

"I see! I see!" he cried. "It's incredible: a quadrumane, a quadrumane that talks! . . . Oh, it's simply incredible!"

"All animals talk," said Coriolis, "but the quadrumane, which is one of the higher animals, possesses a greater variety of distinct sounds than the other beasts to express desire, pleasure, hunger, thirst, terror and so on: very distinct sounds and invariably the same. These utterances, therefore, from a language. In my pithecanthrope, which is the chief of the quadrumana, the one most nearly related to man, I have discovered as many as forty distinct sounds."

"And you went on the principle that, if an animal can pronounce forty sounds, it can pronounce every sound?"

"Open your mouth, Balaoo," said Coriolis.

Balaoo, who was ready to die of shame, had no time to protest. Coriolis, after holding his shoe-hands, was now holding his two jaws, without any antiseptic preliminaries, and working them on their coronoid processes as though he were setting a wolf trap. Balaoo foamed at the mouth; and his large, round, gentle eyes shed tears as they contemplated Madeleine, who was sadly watching the operation. Even so the sufferer who is having a tooth extracted gazes mournfully and gloomily at the staunch friend who had accompanied him to the dentist's.

"He has magnificent teeth," said M. de Meyrentin.

"Never mind the teeth, my dear sir," said Coriolis, impatiently "Just look at that pharynx! I have always said and I have always written, 'Every faculty, functional and anatomical, moral, intellectual and instinctive,' depends upon the strueture; and, as the structure tends to vary, it is capable of improvement.' "

"He doesn't see that he's spitting in my mouth!" thought Balaoo.

"You have perfected the pharynx," said M. de Meyrentin, "altered the back of the throat, worked at the vocal cords; and that was enough, you say, to enable you to turn a monk . . . a quadrumane, I mean, into a man?"

"Why not?" said Coriolis, letting go the jaw for a moment. "It is not difficult to show that no absolute structural line of demarcation, wider than that between the animals which immediately succeed us in the scale, can be drawn between the animal world and ourselves."

"All the same, my dear sir, there is an immense gulf between the monk . . . the animal, I mean, and man."

"No one is more strongly convinced than I am," answered Coriolis, continuing to quote the late Professor Huxley, "of the vastness of the gulf between civilized man and the brutes. No one is less disposed to think lightly of the present dignity or despairingly of the future hopes of the only consciously intelligent denizens of this world; but, even from this intellectual and moral point of view, I contend that, by modifying the structure, it is possible to fill up the gulf."

"What you say fills me with admiration and, at the same time, with terror."

Within himself, the magistrate thought:

"It's you who will be filled with terror, presently, when I tell you what your advanced theories have brought you to!"

For M. de Meyrentin, the cousin of the great Meyrentin of the Institute, had remained an idealist and an anti-Darwinian, like the pride of the family.

"Nonsense!" said Coriolis, aloud. "What is it that makes man what he is? Is it not the faculty of speech? Language enables him to note his experiences; language increases the scientific assets of the generations that follow one upon the other. It is thanks to language that man is able to link together more closely his fellow-creatures distributed over the face of the globe. It is language that distinguishes man from the rest of the animal world. This functional difference is immense and the consequences are extraordinary. And yet all this can depend on the very slightest alteration in the conditions of the back of the throat. For, what is this gift of speech? I am speaking at this moment; but, if you change in the least degree the proportion of the combined forces at present in action in the two nerves that control the muscles of my glottis, I become dumb at once. The voice is produced only so long as the vocal cords are parallel; they are parallel only so long as certain muscles contract in a similar fashion; and this, in its turn, depends upon the equal action of the two nerves of which I have just spoken. The least change in the structure of these nerves and even in the part from which they spring, the least alteration even in the blood-vessels involved, or, again, in the muscles which the blood reaches, might make us dumb. A race of dumb men, deprived of all power of communicating with those who can speak, would be a race of brutes."

"Just so, just so," said the magistrate.

"It goes without saying," continued Coriolis. "Don't scratch yourself, Balaoo!"

Balaoo, who hought himself unobserved, was covered with shame.

"Well, what I have done is the opposite of one aiming at producing dumbness: I have aimed at increasing the scope of an organ which was already capable of emitting certain sounds of speech. I have held all those nerves, all those muscles, all those arteries in my forceps, for the greater glory of my demonstration."

Balaoo, who had been under an anæsthetic during the operations, listened to all this with a very casual interest.

"And I have succeeded in producing the necessary parallel position of a quadrumane's vocal cords. Open your mouth, Balaoo."

Balaoo opened a terrible wide mouth, which Coriolis at once turned back under the lamp, and asked himself when on earth this awful torture was coming to an end.

"Look, my dear sir, look . . . there . . . you can still see the scars . . . "

"It's astounding, it's astounding! . . . And he now talks like a man . . . But has he also retained the power of emitting the animal sounds which he used to?"

"Yes, but it takes him a greater effort than it did. Speak as you used to, Balaoo."

Balaoo, by way of revenge and of joking, began to speak as he used to in the old days, but as he used to when he was angry, that is to say, when his voice could be heard for a mile around:

"Goek! Goek! Goek! . . . Ha! Ha! Ha! Hâââ! . . . Hâââ! . . . Hâââ! . . . Goek! Goek! . . . "

The magistrate, Coriolis and Madeleine put their fingers to their ears and made violent signs to Balaoo that that was enough. He ceased; but Coriolis explained what he wanted:

"Talk as you used to, but not so loud. We can't hear ourselves speak."

Thereupon Balaoo "talked" as he used to, but mezzo voce, while Coriolis expatiated on the virtues of the pithecanthrope's throat:

"You see," he said, to Meyrentin, "how the capacious membranous pouch, situated beneath the throat and communicating with the vocal organ, with the laryngeal ventricle, swells. Look at it: it swells and swells and swells! The louder he speaks and shouts, the more it swells; and then it resumes its normal shape when he stops."

"Goek! Goek! Goek!" said Balaoo, more and more embarassed by the singularly persistent gaze of the man who sent thieves to prison.

"And what does 'Goek' mean?" asked M. de Meyrentin.

"It means, 'Go away,' " said Balaoo, who was not without a sense of humour.

"Why," observed M. de Meyrentin, "it's almost like the German 'Geh weg!' "

Balaoo did not know German and declined to pursue the subject; and M. de Meyrentin stayed on.

Balaoo heaved a sigh: he had never suffered so much in all his life. A hand took his tenderly. Oh, Madeleine! And Balaoo's heart began to thump inside his breast. Ah! M. de Meyrentin was getting up. Did he mean to go, this time? . . . Did he? . . . Yes, yes, at last! . . . He offered Coriolis "all his congratulations" . . . like an ass, like an ass! . . . He seemed to be fairly laughing at Balaoo and to be planning something which Balaoo couldn't make out: one must always be careful with those people who send thieves to prison . . . And it was foolish in any case, of M. Herment de Meyrentin to appear to make little of Balaoo, for this business might turn out badly too!

The magistrate said, with icy deliberation:

"All my congratulations, my dear sir. You have made a man-child. What with science and your scalpel, you equal the Creator!"

Coriolis thought that he was exaggerating and told him as much. M. de Meyrentin confessed that he was exaggerating. With an insolent glance at Balaoo:

"Yes," he granted, "it's true. The Creator made them handsomer."

He uttered this in front of Madeleine. Balaoo, at first, choked. His astonishment paralyzed him, stupefied him. Coriolis, seeing the pain which his visitor had given to his pupil, to the child of his creating, tried to speak a word of comfort:

"Yes, the Creator has made handsomer men," he said, "but none gentler, better, more loving, or more faithful. This one has amply rewarded his old master for all the trouble which he gave him at first; for I admit that it was difficult, during the early years, to make him forget his games in the Forest of Bandong. But now he is absolutely, as I contend and am prepared to prove, a member of the human race."

At this speech, which ought to have touched him, M. Herment de Meyrentin grinned like a fool and, pointing to the torn overcoat and trousers, said:

"Humph! He still indulges in a little prank at times!"

Balaoo could have wept, but he controlled his tears in the presence of a stranger. And kind Dr. Coriolis gave the magistrate his answer:

"I have known men's children who were not more than seventeen years old and whose parents would have been thankful if they had spent their time climbing the trees after apples and tearing the seats of their trousers in the process. It is not for me to advise you, my dear sir, to consult the records of the criminal courts. You know as well as I do how some men's children employ themselves at seventeen, with knife in hand!"

"The master's right," thought Balaoo. "I have never struck anyone with a knife. That's all very well for men-children, who have no strength in their hands."

"In your part of the country, M. Coriolis," said the magistrate, in a tone of voice that made Balaoo look asquint, "people don't use the knife in committing murder. They strangle their victim. Their fingers are all they want."

Balaoo blinked his eyes and thought:

"What made him say that, I wonder?"

Corlolis, pointing to Balaoo's hand, observed:

"There's a hand that wouldn't hurt a fly!" "You insist upon that fly of yours," thought Balaoo, timidly, with lowered eyes, for he was an admirable dissembler, "but I, who wouldn't hurt a fly, would not at all mind strangling this distinguished visitor!"

M. Herment de Meyrentin, remembering that his illustrious cousin in the Academy had always combated the Darwinian theory with rather antiquated arguments about the impossibility of indefinite reproduction among mixed species, refused to leave without a Parthian shot to give Coriolis something to think about. What right had the imprudent doctor to let loose the evil instincts of the Forest of Bandong upon civilized human society? Well, he would be punished for it before supper by the arrest of his pithecanthrope, whom M. de Meyrentin fully intended to come back and fetch with his posse of gendarmes. And, in his finest, throatiest voice, the magistrate let fly:

"I congratulate you, my dear sir. All you now have to do is" --- here de Meyrentin's features widened into an infamous smile --- "to get him married. He will soon have attained the legal age. I hope that you are already thinking of the young lady whom he will lead to the altar. Mlle. Madeleine will be bridesm . . . "

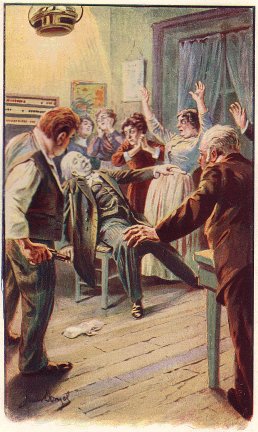

M. Herment de Meyrentin was unable to finish either his smile or his sentence, for he felt round his throat the grip of two clutches contracting with a force that was positively alarming to a member of the Human Race who still hoped to spend many a year upon this earth, utterign foolish and unseemly words. He gurgled, he struggled, he choked! Balaoo squeezed and squeezed. Coriolis and Madeleine uttered yells of terror and hung on to Balaoo to make him let go. Coriolis seized a poker and rained blows with it upon Balaoo. The blows sounded as though they were striking a drum; but Balaoo felt nothing. Madeleine wept and sobbed and prayed and raved; but Balaoo heard nothing. He squeezed!

And he did not stop squeezing until M. Herment de Meyrentin stopped struggling. That would teach the gentleman to think that Balaoo, who wouldn't hurt a fly, was not handsome and to make fun of him in front of marriageable girls! A nice thing the gentleman had done for himself: he was dead!

Dead was M. le Juge d'Instruction Herment de Meyrentin, first cousin of the illustrious Professor Herbert de Meyrentin, member of the Institute, secretary of the moral and political science section! A whole family cast into mourning! A most distinguished family! That was all that remained of that mighty exemplar of human power, an examining-magistrate! A rag, a doll broken over a pithecanthrope's arm!

Balaoo flung that offal to the ground. He was astounded to see kind Dr. Coriolis glue his ear to the thing's chest. There were some people who didn't mind what they touched! But where was his little sister Madeleine? Balaoo looked round for her and discovered her standing flat against the wall, with her mouth wide open and her eyes glittering with fright.

"It's clear to me," thought the pithecanthrope, "that I've made a blunder here. They don't look a bit pleased!"

Coriolis rose to his feet as pale as death:

"Wretch!" he raved. "What have you done? You have murdered your guest! "

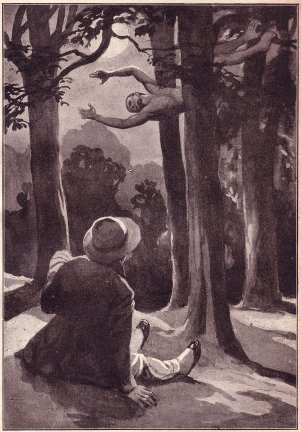

"Tut!" thought Balaoo. "Why do they get into such a state? What worries them is the corpse, I can see that! And I expect they are afraid of the commissary of police, who always arrives when you hurt a member of the Human Race. For instance, you can murder my friend Huon, the great old bachelor wild-boar, who was nicely killed with a stab in the heart in the presence of everybody, and nobody to say a word against it, or my friend Dhol; the big old lusty wolf, whom they riddled with bullets because he ate a six-months' baby that hadn't yet learnt to say 'Papa' and 'Mamma,' but you've no right to strangle one of the Human Race, just like that, with your hands. It's the law. All right! All right! I'll take away the corpse; and no one will be any the wiser. I'll hang this one too: that will be a good trick!" "So thinking, Balaoo took M. Herment de Meyrentin's big, flabby body by the hind legs and dragged it to the door. Coriolis tried to stop him, but Balaoo shouted, "Goek! Goek!" in so loud a voice that Coriolis soon saw there was nothing to be done with the pithecanthrope at such a moment. Balaoo was all on edge, excited, glorying in his terrible work. He wouldn't hurt a fly; but, for all that, Dr. Coriolis realized that it would be unadvisable to part him from his prey, which the pithecanthrope was dragging behind him with a pride as conscious as that of a Roman general carrying the spolia opima in his triumph. Oh, what a lofty brow was Balaoo's and how well fitted to wear the laurel-crown! There is a Roman general in every monkey! . . . And bang! One good kick with his shoe-hand to the door; and it opened wide to let the procession through.

Madeleine was powerless to stir a limb and Coriolis was still shaking like a poltroon when Balaoo, with his burden, solemnly made his way under the branches of the neighbouring forest.

Having filled her basket, Mme. Mûre cautiously opened her door. The church-clock struck the hour. More doors opened in the direction of the Cours National. Other little old women poked out their caps in the moonlight, hesitating to cross the threshold, having lost the habit of leaving the house after supper. True, people were nearly easy now that those horrid brothers Vautrin were comfortably stowed away in prison and about to pay their debt to society; but, all the same, it was impossible to throw prudence to the winds from one day to the next.

Ohoo! Ohoo! Shadows on the road, swinging lanterns as they went: it was M. Roubion and his inn-servants to summon the embroiderers to sit up with the Empress of Russia's gown.

The little doors opened wider: the little white caps ventured forth, hand-basket on one arm, foot-warmer hanging from the other. Oh, they knew better, in this harsh weather, than to go out without their warming-stools, the coals in which, for years and years, had scorched the skin of their legs to such good purpose that many of them, no doubt, had nothing but a pair of burnt sticks to show under their skirts.

Ohoo! Ohoo! They pattered and clattered along, after carefully locking their doors. It was the last evening which they were to spend on the Tsarina's gown; and they would not have missed it for the empire of All the Russias. Two hours' work and it would be done; the contractor was coming to Saint-Martin next morning to fetch the dress. At least, so Mother Toussaint, the forewoman who had arranged with the contractor, said --- the old gossip! --- perhaps to stimulate their zeal.

The procession went flapping and clapping down the Rue Neuve. Shutters were flung back against the walls as it passed. More than one would have loved to be invited to go and see the Empress'gown and not all who had been long in bed were yet asleep.

Big Roubion increased his pace. No one wanted to loiter. They trotted and trotted. It was cold; and the women had lowered their hoods over their caps; and their shoulders shivered, in spite of all, less with cold than with fear, at the thought of the Three Brothers, who loomed large in the shadows of the night.

There was a full gathering at Mme. Roubion's for the last evening with the Empress'gown. The embroiderers worked in the large summer dining-room, which was used for the commercial travellers in the fine season, but closed in winter. The wonderful gown lay spread at full length on the leaves of the dining-table; and each of the needlewomen took her seat. Two of them made the eyelets, another the raised spots, another finished a rosette, another worked at the scalloped edges and two assistant hands, working side by side, sewed on some old lace. Mme. Toussaint, that old gossip, supervised everything and worried everybody. Mme. Roubion, with her enormous head resting on her capacious bosom, had eyes for none but her guests. After the bar-room was closed, monsieur le maire arrived, accompanied by Mme. Jules, his spouse; M. Sagnier, the notary, and madame, who possessed such beautiful false pearls; and M. Valentin, the chemist, and madame, who was the only lady in the neighbourhood that used make-up --- and such a lot of it! --- and who was also the only lady that could boast of having had an adventure, last autumn, at the manúuvres, with a cavalry-officer. All these fine folk had come to admire "the masterpiece of French industry" before its departure for the Russian court.

Now this dress, which, at any other time, would have kept twenty talkative women wagging their tongues for an hour, left the ladies very indifferent in ten minutes or even less. To begin with, they thought it too simple in its immaculate splendour. It was an all-white dress, of embroidered cloth, and Saint-Martin-des-Bois could not picture the Empress of Russia other than adorned like a reliquary and swathed from head to foot in gold, precious stones and silver lace. Mme. Jules considered it hardly even a dress for the seaside. The embroiderers could have boxed her ears; and Mme. Toussaint, the old gossip, felt that she would like to scratch her eyes out. The ladies gradually left the summer dining-room to join their husbands in the bar-room, where they found the gentlemen sitting round the fire, cracking a bottle of old wine and discussing the Vautrin case. Oh, how that case had been discussed since the arrest! But it was apperently always new; and, now that "they" were going to be guillotined and that there was no longer any reason to fear them, people were almost proud of having been so afraid. Nevertheless, no one was willing to admit his terrors. On the contrary, each vied with the other in trying to show that it was he who had "handed over the Vautrins to the public vengeance." Through the half-open door, the embroiders, who also thought of nothing but the Three Brothers, heard the chemist and the notary each boasting of his courage at the trial, where they had smashed the ruffians with their evidence. True, by that time, the verdict against them was certain, because they had been captured red-handed: the gendarmes had appeared in the road at the moment when Élie, Siméon and Hubert were taking Bazin the process-server's money-bags from him, after stunning him with that little pat on the head of which he died. However, it must be admitted that, in order that this verdict might be far-reaching and allow none of the three prisoners to escape, M. Sagnier and M. Valentin had taken advantage of the Bazin murder to saddle the Vautrins with all the suspicious matters that had distressed the district for the past ten years.

The chemist and the notary each enlarged upon the merits of the civic heroism displayed by himself at a time when no one else seemed to retain a proper sense of his duty; monsieur le maire knew what was meant!

All this self-sufficiency and self-conceit ended by annoying the people present, down to the needlewomen in their work-room; and even Mme. Mûre coughed as she swallowed her poppy seeds. As for Mlle. Franchet, that worthy could not keep from chuckling and spluttering into the bowl of mulled wine which Mme. Roubion had brought her, with a word of warning not to stain the Empress of Russia's gown. They knew and everybody knew that those two who were now posing as dare-devils had been very meek and mild indeed while the Vautrins were about.

Had the needlewomen been in monsieur le maire's place, they would soon have made them put a stopper on their loquacity. The same thought occurred to monsieur le maire himself. It was not a very happy thought, however; for, when he reproached the gentle men, not without a touch of irritation, with having waited so long to accuse men of whose crimes they were cognizant, he was told, in reply, that, "but for the fortunate incident of the murder of the process-server, where the Vautrins were caught red-handed, there would have been every reason to pity decent people who were so ill-advised as to inform against such powerful election-agents as the brothers Vautrin."

The mayor bit his lips and Mme. Jules, his spouse, made a sign to him not to go on embittering the conversation. Nevertheless, he retorted that he was not the only one to be elected to the municipal council with the Vautrins' aid. His two subordinates protested loudly and called Heaven to witness that they had had no finger in that pie and that, at any rate, they had never been mixed up in the dirty jerrymandering of the general elections; and they didn't mind saying so; and, if anyone chose to take offence, that was his affair.

M. Jules, the mayor, of course, could not take this insult lying down; he did his best to pass it off by saying that, if anyone had the right to boast that he had brought the truth to light, it was good old Dr. Honorat. Ah, there was one who had spoken out! And said useful things too! He had supplied the proof of the murders by speaking of the rope with which the men were hanged.

"Agreed," retorted Mme. Valentin, the local lady who had had that adventure with the cavalry-officer, "agreed; but, as M. le Vicomte de la Terrenoire" --- the officer in question --- "said at the trial, considering that Dr. Honorat examined the bodies in the commissary's presence, why did he not then call the attention of the police to the kind of rope with which the men had been hanged and which he thought that he had already noticed at the Vautrins' on the day when he was called in to attend Zoé?" And she concluded, "If Dr. Honorat was more useful than anybody afterwards, he was more prudent than all rest of us before!"

To this, Mme. Jules, the mayoress, replied:

"He had the right to be, or, at least, he had every excuse. Dr. Honorat drives along the roads, night and day, all alone in his gig; and an accident is easily met with. What could he have done against those three ruffians?"

"He preferred to nurse them," hissed long, lean Mme. Sagnier, the lady with the false pearls, between her teeth. "It was he got them sentenced to death," resumed the mayor, in an authoritative tone, "and, I repeat, he showed courage in doing so, for, as long as I live, I shall never forget Siméon jumping up from his seat in the dock, shaking his fist at Dr. Honorat and shouting, 'You'd better mind yourself, for, if ever I get out of this, my first visit will be paid to you!' It was enough to give one the shivers. Well, Dr. Honorat did not turn a hair. He's a brave man, I tell you."

The two others raised their voices in protest:

"And what about us, weren't we threatened? Élie and Hubert said to us, 'You are liars; and, the next we meet you, we'll break your heads.' Those are the very words."

"I had to keep my bed for a fortnight after," declared Mme. Valentin"

"So had I," said Mme. Sagnier.

There was an embarassed silence, which was interrupted by fat Mme. Roubion, who went round among the company with her bowls of mulled wine:

"That's not thc point," she said. "What's the use of arguing, now that their business is settled? When are their heads to be cut off? They ought to have been cut off here; but, as the thing's arranged to take place at Riom, has monsieur le maire thought of engaging a window?"

"Look here," said M. Jules, roughly, "I'd rather talk about something else . . . "

And, for the next five minutes, they talked about nothing at all. Everybody sat steeped in thought and one and all had the same thought: they would not be really easy in their minds until the Three Brothers were dead and buried. There was only one fear, that the President of the Republic might commute the sentence of one of them; and, after all, people had been known to escape from prison. You never could tell . . .

Mme. Roubion made a fresh effort to dispel the figures of the Vautrins:

"You know Mlle. Madeleine Coriolis is to be married soon?" she said.

"Oh, nonsense!" said Mme. Valentin. "To whom?"

"Why, to M. Patrice Saint-Aubin, her cousin from Clermont."

"There was a rumour of it," said Mme. Sagnier, "but they have lots of time before them. He is quite young still."

"Quite young?

He's twenty-four," said Mme. Roubion, "and he has just passed as a solicitor. His father is anxious to make over his practice to him. He wants to see his son fixed up and married and settled behind his papers in the Rue de l'Écu before his death, for the old gentleman does not think that he has long to live."

"He's right there," declared the chemist. "You can't be too careful. One never knows who's going to live and who's going to die."

"They say the Saint Aubin boy is rich enough for two," said Mme. Valentin. "Has little Madeleine any money?" All the company were of opinion that she had not. Dr. Coriolis, an old eccentric, who used to be consul at Batavia, might have made his fortune in the Malay Archipelago, but the general view was that he had returned from the Far East with nothing but a fatal passion for the bread-plant, which had made away with his last shilling. Did anyone ever hear of such madness? To try and make a single plant take the place of bread, milk, butter, cream, asparagus and even Brussels sprouts, which he pretended that he was able to make out of the waste! And for years he had been living with his hobby, at the bottom of his immense garden surrounded by tall walls behind which he lived in a state of almost complete isolation, seeing nobody and refusing to be assisted by any one except his gardener, a boy whom he had brought with him from the East and who seemed greatly devoted to him. He was a very nice young fellow, that Noël, that they must say: a little shy, never talking to anybody, but always bowing to everyone most politely. When he crossed the street; for his master sometimes sent him on an errand, he nearly always carried his hat in his hand, as though he lived in fear of "offending somebody."

"He's not what you would call good-looking," said M. Roubion.

"He's not ugly either" said Mme. Valentin. "Only, he's rather flat-faced." "He's like all the Chinese," said Mme. Roubion, pedantically, having seen "Celestials," as she called the inhabitants of the Celestial Empire, at the Exhibition of 1878. "They are not handsome, but they look very intelligent and not the least bit ill-natured. My opinion is that he's a Celestial."

And Mme. Jules summed up the general view on Noël by asserting that "he wouldn't hurt a fly."

In the summer dining-room, the needlewomen, seated around the Empress' gown, ceased to listen to the ladies' and gentlemen's conversation as soon as they had finished talking about the Three Brothers. These alone had the gift of interesting Mme. Toussaint, Mlle. Franchet, Mme. Boche and Mme. Mûre, though on this subject the good women were inexhaustible, always finding new things to say and even repeating the old things over and over again, without ever wearying. They were fellows who were not satisfied with being highway robbers, said one, but who did wrong for its own sake, in other words, for their pleasure. Mme. Boche told how she had nearly died of fright, last year, one evening when she was closing the shutters of the little shop where she dealt in groceries, haberdashery, deal boards, laths and coals. She maintained that one of the Vautrins had hidden on the roof of her house --- Mme. Boche's roof almost touched the ground --- and snatched off her cap and wig. She was almost sure that she had recognized Élie, unless it was Siméon, unless it was Hubert, but it was certainly one of the Three Brothers, who, when they were not murdering people on the roads, spent their time frightening old women. Oh, the Vautrins had broad backs! Mme. Mûre shed tears over the decease of a poodle which met its death in a very curious way, one evening when it was barking too loudly at the heels of the Vautrins, who were preparing some trick. It suddenly ceased barking. Mme. Mûre went out into the yard and found her dog hanging from the rope of the well. This suicide, which was at least as difficult to explain as Camus' and Lombard's, had been as it were a signal for the suicide of all the dogs in the village at that time. It was a regular epidemic. The dogs were all found hanging from the well ropes, So much so that, since then, Saint-Martin-des-Bois had given up keeping dogs.

Mme. Toussaint shook her fat chops and hcr flabby chin under her mob-cap:

"And, then, if they had only been satisfied with the dogs!" she said. "Those wretches need not have thrown my little cat Mirette into the pond, with a stone round her neck, for us to know them for savages. Their reputation was made!"

In short, "life had become a hell;" but, since "they" had been in prison, people had recovered their peace of mind to some extent and the old ladies of Saint-Martin were once more beginning to enjoy life.

It was at that moment, just as the several visitors at the Black Sun were expressing their contentment with a state of quiet to which they had long been unaccustomed that a mad sound of galloping was heard on the rough cobbles of the Rue Neuve. This galloping was accompanied by the noise of a light vehicle, a noise which could only belong to Dr. Honorat's gig. Everybody recognized it; and the proof was that everybody cried:

"There's Dr. Honorat!"

But what had happened? Why that din? Why that hurry? Had his horse taken the bit between its teeth and run away? Had the doctor dropped the reins?

Mlle. Franchet cried:

"Perhaps he's been murdered!"

But everyone was at once reassured, at least in so far as Dr. Honorat's existence was concerned, for he was heard shouting, in a hoarse voice:

"Open the door! . . . Open the door quickly! . . . "

M. Jules, the mayor, M. Roubion, M. Sagnier and M. Valentin drew their revolvers, without which they had not sallied forth for many a long day; and the ladies, seeing their husbands produce those lethal weapons, began to tremble and were unable to utter a word.

"What's the matter?" asked Roubion, putting his ear to the door.

"Open the door, can't you? It's I, Dr. Honorat! Let me in, Roubion, let me in!"

"Are you alone?" asked Roubion, prudently.

"Yes, yes, I'm alone, let me in!"

"You can't keep the doctor standing at the door," Mme. Roubion declared. "Let him in."

Everybody at once fell back, while the needlewomen, leaving their work, gathered anxiously in the doorway between the bar-room and the summer dining-room.

Roubion opened the door.

Dr. Honorat, who had fastened his panting horse to the ring in the wall, burst into the room like a whirl-wind. Roubion bolted the door behind him and all clustered round the doctor, who had promptly sunk into a chair. He was deathly pale. He was hardly able to speak. His eyes were wild and staring. He managed to groan:

"The Vautrins! . . . The Vautrins! . . . "

"What about them? . . . What about the Vautrins? . . . "

"The Vautrins are here! . . . "

Everybody shrieked. Fear sent its gust of madness over them, flinging up their arms in meaningless gestures, tossing the company this way and that way, making them writhe and twist as though they had all suddenly lost their mental balance:

"Eh? . . . What? . . . Where? . . . The Vautrins? . . . What's he talking about? . . . The man must be mad! . . . Where did you see them? . . . "

"At their own place!" gasped the doctor. "At their own place! . . . In their house! . . . "

"He's been dreaming! . . . He must have been dreaming! . . . "

The chemist and the notary were now as pale as the doctor. They did not believe him. They did not think that such a thing was possible; but, all the same, from the very moment of his stating the incredible horror, it left them as though stunned, with arms and legs paralyzed, throats dry and hearts beating like mad.

The nameless terror depicted on their faces seemed rather to exhilarate monsieur le maire who, after a rapid examination of conscience, arrived at the conclusion that, throughout this business, he had preserved so prudent an attitude that he had nothing to fear from the vengeance of the Three Brothers. He showed the coolness which should never desert a chief magistrate in the presence of his fellow-citizens. He silenced the silly moans of the needlewomen and the incoherent questions of the ladies.

"Come, doctor," he said, "don't lose your head like this. Are you quite sure that you saw them?"

"As sure as I see you now."

"In their house,by the roadside?"

"In their house. They had not even drawn their window-curtains. I was coming down the road, on my way back from my rounds. My mare was going at a slow trot. I saw a cart outside the Vautrins' door and a light in the windows; and I seemed to hear voices. I had a sort of feeling that I should come upon something unexpected. And I was not mistaken. I was just passing the door, when the door opened and I saw, as plainly as I see you, Élie, Siméon and Hubert quietly carrying a chest out to the cart. I at once whipped up my mare; and she galloped off. But they had caught sight of me and recognized me, they shouted after me, 'See you soon, doctor!' I thought I should go mad! . . . Oh, I thought they were behind me; and I rushed on like the very devil. I felt that I was done for, if I did not reach Saint-Martin before they did. For they are coming! . . . They are coming! . . . "

"Don't talk nonsense, doctor," monsieur le maire broke in, speaking in his most serious tone. "If it's really they, then they've escaped from prison and will never dare come here."

"I tell you, they are coming. They told me so in court! I'm a dead man! . . . "

As he spoke, good old Dr. Honorat, decent man, who, perhaps, before this fatal meeting, had taken a pint of old wine more than he need have on his rounds --- for he did himself pretty well --- Dr. Honorat, I was saying, noticed the white faces of M. Sagnier and M. Valentin and had the satisfaction of remembering that they too had been threatened at the trial; and he put his satisfaction into words:

"And you too, M. Sagnier! . . . And you too, M. Valentin! . . . You are both dead men!"

M. Sagnier shook his head and said, in an expiring voice:

"It's not true, what you're saying; it's impossible!" M. Valentin shared this opinion. He whispered:

"How can they have got out of Riom gaol? It's impossible!"

This was clearly the key-note of the situation; and everybody repeated:

"No, no, it's quite impossible!"

Monsieur le maire smiled at seeing people so frightened: "Come, ladies," he said, "pull yourselves together. Our worthy doctor has been imagining things. Give him a glass of mulled wine, Mme. Roubion; that will do him good."

"I don't want anything," said the doctor; and his eyes wandered more wildly than ever over the company.

Monsieur le maire shrugged his shoulders and, seeing Mme. Toussaint, Mme. Mûre, Mme. Bache and Mlle. Franchet gathered round him like so many hens who had sought refuge under their rooster's wing, he packed them back to their work. Clucking with anxiety, they returned to the summer dining-room; but no sooner were they there than they uttered such screams that it was now the turn of those in the bar-room to go after them. They found Mme. Toussaint, the old gossip, indulging in an orthodox fit of hysterics. The Tsarina's dress had disappeared! . . .

The mystery surrounding the incident was so profound that nobody doubted that "there were Vautrins at the bottom of it." It resembled too closely a number of other indoor disappearances which had never been explained and which had always been put down to the Three Brothers. No one now doubted that Élie, Siméon and Hubert were back and that they had performed the miracle of escaping from the executioner's knife with the one and only object of rushing to Saint-Martin-des-Bois and stealing the Empress' gown. And, if M. Jules, the mayor, who had always had a sneaking kindness for those scamps, because of the relations which they kept up with the elected representatives of the nation, if M. Jules still hesitated to yield before the evidence, his hesitation did not last long. For there came a fresh knock at the door of the Black Sun; and the person who knocked seemed in as great a hurry to obtain admission as Dr. Honorat himself had been. An awful silence at once reigned inside the inn, for all were wondering if they were about to hear the voices of the Three Brothers. But no, it was the trembling voice of an old lady entreating to be let in; and everybody recognized Mme. Godefroy, the Saint-Martin postmistress.

"An official telegram! An official telegram for monsieur le maire! Open the door, M. Roubion, it's very urgent. O Jesus, Mary, Joseph!"

Mme. Godefroy's terror must have exceeded all bounds for that respectable functionary to neglect the last counsels of prudence and to dare invoke the saints of the Roman and Catholic paradise within two steps of her lord and mayor, who had distinguished himself by his stalwart paganism at the time of the separation of Church and State.

"Monsieur le maire is here, Mme. Godefroy," Roubion shouted, through the door."

"I know that," replied the other. "Let me in."

The mayor, greatly perturbed, said:

"An official telegram? Push it under the door, Mme. Godefroy."

"Never will I push an official telegram under the door!" declared the unhappy woman. "I must deliver it into monsieur le maire's own hands . . . "

"Let her in," said M. Jules, heroically.

The door was half-opened and Mme. Godefroy appeared.

She wore the same mortal pallor, the same wild, staring eyes that had marked the entrance of Dr. Honorat. A yellow paper shook between her fingers. Monsieur le maire took it from her and read the contents of the official telegram aloud:

"Prefect PUY-DE-DÔME to Mayor SAINT-MARTIN-DES-BOIS.

"Three brothers Vautrin escaped to-day from Riom gaol; take necessary steps."

The mayor, who had no armed forces at his disposal, beyond his beadle and his town-crier Daddy Drum, flung a lifeless, circular glance at those around him. The poor people seemed to have lost the power of breathing. M. and Mme. Sagnier and M. and Mme. Valentin held each other clasped in a tight embrace, forming two couples similar to those in the pictures representing the early Christian families thrown to the lions. Dr. Honorat, in his chair, gave not a sign of life. The band of little old needlewomen clustered round buxom Mme. Roubion; who, with her two hands laid flat on her enormous breast, made a vain effort to control the beating of her heart. And the terror was so great that Mme. Toussaint herself, who was supported by Mme. Boche, who was supported by Mme. Mûre, who kept a tight hold on Mlle. Franchet's hand, Mme. Toussaint herself had ceased her lamentations on the disappearance of the Empress of Russia's dress.

Monsieur le maire read the official telegram for the fifth time, without deriving from it the inspiration that would have saved him at this difficult moment. For everybody was relying on him. He kept on repeating:

"Take necessary steps . . . take necessary steps . . . he's a nice one, the prefect! . . . What necessary steps would he have me take? It's for him to take the necessary steps . . . He ought to have sent us some gendarmes by now . . . He must have known that 'they' would come back here . . . "

Three loud bangs on the bar-room door . . . Everybody gave a fresh jump. And a voice in the street said:

"Quick, quick! Let me in! . . . It's I, Clarice. Open the door, in Heaven's name!"

"Camus' clerk! We ought to put out those lights. We shall have them all coming here," cried Roubion.

But the other kept thumping at the door for all he was worth:

"Let me in! Let me in! . . . "

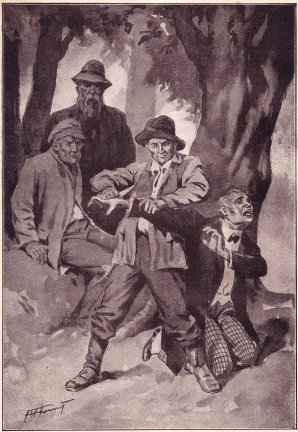

They opened the door, but swore that this was the last that they would admit. He was even more scared than the others; and he had every reason to be. He had not seen the Three Brothers, but he had bumped up against M. de Meyrentin's body hanging on a tree on the Riom Road. Oh, how they all screamed! The Vautrins were beginning their revenge! Lord, what would happen next?

The cries were followed by general consternation, by mute despair; and then this assumed yet a fresh shape as was to be expected. While monsieur le maire was reflecting upon the melancholy of the situation, without being able to come to the slightest decision, he suddenly saw a furious spectre brandishing its fists in his face.

It was Dr. Honorat, shouting at him: "This is all your fault!"

It needed nothing more to inspire the rest with courage.

The notary and the chemist attacked the mayor at once; of course, it was his fault! But for him, none of this would have happened! But for him, those ruffians would long since have relieved the country of their presence! But they had found a mayor to encourage them, to reward them! Every time they committed a misdeed, a crime, the mayor gave them money! And that, no doubt, was how they had escaped, by bribing their warders with the gold of the municipality and the elections!

The wretched mayor could not get a word in edgewise. Everybody was now shouting:

"You have made yourself their accomplice, their accomplice!"

Dr. Honorat, with his eyes starting from his head, let fly the word:

"Murderer!"

And they made so great a noise that they did not hear some one rapping, this time at the gate of the yard, with the heavy knocker.

Mme. Boche it was who went and listened in the passage. She returned, waving her arms, while her legs gave way beneath her:

"Hark! Hark!"

All were silent; and, as the knocking had also ceased, everyone heard a rough voice in the distance calling monsieur le maire.

This time, there was no mistake about it: Hubert, the eldest of the three Vautrins, was outside! They knew his voice; and, as he was the most dreadful of the three, there was a general rush to the darkest corner of the bar-room. The women began to squeal like cats that were being skinned alive. But monsieur le maire, whom madame was holding back by the skirts of his jacket, broke away from the trembling band and said to the innkeeper:

"Come, Roubion, we must find out what they want. You've never had any bother with the Vautrins; have you?"

"Never! Never!" proclaimed Roubion, hurriedly, with obvious satisfaction. "No, no, there's never been anything between us."

"I won't have you go, for all that," whined Mme. Roubion.

"Then I shall have to go alone," said the mayor, laughing.

At that moment, the knocking at the gate started afresh.

Roubion pulled himself together:

"Monsieur le maire is right," he said to his wife. "They can't mean harm to people who have never done them any. I never refused them a glass of wine when they came here. What do you imagine they could do to us? Perhaps they want a drink . . . "

"You're not going to let them in?" sobbed Mme. Valentin.

"No," said the mayor, "but we can talk to them."

"I'll open the spy-hole in the gate and we shall soon see what's up," said Roubion.

"It's quite true, I've never failed them. I've always treated them well. Why should they wish us harm?" argued Mme. Roubion. "If they're thirsty, we can always hand them a bottle through the spy-hole. So let's all go together."

"That's it," said the mayor. "We'll all go together." Nevertheless, none except the mayor and Roubion, followed by their wives, left the bar-room and ventured under the archway of the yard. And even then Mme. Jules and Mme. Roubion remained at the entrance to the archway. As for the others in the bar-room, they did not make a movement. The women had ceased squealing. There was not a sound heard but their heavy breathing.

The mayor and Roubion were away for at least five minutes, which seemed an eternity. They returned at last, still accompanied by their wives. When they entered the bar-room, the others saw, by their awe-struck faces, that they had no good news to tell. Dr. Honorat, the chemist and the notary kept their eyes fixed on monsieur le maire, waiting for him to speak. And no prisoner in the condemned cell, watching the magistrate who comes, at break of day, to tell him that his petition for mercy has been rejected, ever felt greater terror in his heart.

"But at least tell us what it is," said Mme. Sagnier, with chattering teeth.

"Well, it's like this," said the mayor, mopping his forehead with his handkerchief. "I saw Hubert through the spy-hole. He wants us to hand Dr. Honorat over to him."

The doctor, on hearing these words, gave a great jump in his chair; and there was a long pause, at the end of which monsieur le maire said:

"I did my duty; I refused."

"Quite right!" said M. Sagnier, who had meanwhile recovered his voice. "Quite right! We are armed. We will defend ourselves here to the death and until the arrival of the gendarmes, who can't be very far off."

"M. Sagnier is right," said M. Valentin, of the pale face. "The ruffians are asking for the doctor because they know that he's here; and, presently, when they know that we are here too, they will ask for us as well, What do they take us for? We won't allow ourselves to be killed like sheep!"

Mme. Sagnier and Mme. Valentin said nothing, but began to glare angrily at Dr. Honorat, who had not spoken a word and who, according to them, should have given himself up at once, to save the rest.

Mme. Godefroy vanquished the tyranny of her nerves, which condemned her to a trembling silence, and asked:

"What answer did he make?"

"He said," replied the mayor, "that he would go and consult his brothers; and he went away."

"Did you think of telling him," asked M. Sagnier, "that they were running the greatest danger by remaining here, that the gendarmes were on their way and that they'd do better to, clear out to some other part of the country?"

"I said all that," the mayor declared, stiffly, "but he told me to mind my own business."

"He has gone away," said Mme. Roubion. "Perhaps they will not come back. Perhaps all of you had better go home."

But one and all protested. They were quite agreed not to leave the inn before daylight and especially before the arrival of the gendarmes who were sure to be sent to Saint- Martin-des- Bois.

"Hark! They haven't gone far!" said Mme. Boche.

The knocking was renewed. The mayor once more drew himself up, like a hero marching to his death, and, with not a sign of weakness, stepped towards the archway. M. Roubion wanted to go with him again; but, this time, Mme. Roubion curtly ordered her husband to stay with her:

"Don't you go mixing yourself up in other people's affairs!" she said.

M. Roubion did not care to dispute the matter and acquiesced.

Mme. Jules sighed out her husband's name and took three steps in his wake:

"What a business!" she moaned. "What a shocking business! It's hard indeed to be mayor under such conditions." And, gazing severely at the down-hearted band, "Monsieur le maire is the only brave man here," she said.

The brave man returned. This time, he was almost as pale as the others. They awaited the decree. He spoke:

"Hubert says that he has consulted his brothers," he intimated, in a flat and shaky voice. "They are all three agreed to murder everybody here, if we don't give Dr. Honorat up to them. I replied that we were armed, that we would defend ourselves and that we would not give up Dr. Honorat."

Hereupon the pack of sempstresses began yelping: they had never had any differences with the Three Brothers; and, if the Three Brothers knew that they were there, they would certainly let them go without hurting them! . . . There was no need for them to stay in the inn! Who knew what might happen? . . . As the Three Brothers only wanted Dr. Honorat, the needlewomen ran no risk in going home. They wanted to go home.

"The doors shall not be opened without my orders," said the mayor. "Besides, you would never get out. Hubert, Élie, Siméon and little Zoé are watching every exit. Hubert told me again and again that they would murder anyone who tried to leave. And they know quite well that you are here."

"And what about us? Do they know that we are here?" asked the chemist and the notary.

"Yes, they do."

"And . . . and . . . and did they say nothing . . . about us?"

"No."

"It's only Dr. Honorat they're after, that's quite clear!" said Mme. Sagnier, with a fierce glance at the unfortunate man.

"Yes, yes," repeated the notary and the chemist, between their teeth, "it's only Dr. Honorat they're after."

"But what do they mean to do?" asked Mme. Roubion, who began to cry like a little girl.

Her example was immediately followed by Mme. Boche and Mme. Toussaint, while Mme. Mûre and Mlle. Franchet still retained a particle of dignity and became reconciled in the moment of misfortune after an estrangement that had lasted for five years:

"There, Mlle. Franchet, there, they won't hurt us!"

"We needn't fear, my dear Mme. Mûre. They would be ashamed to!"

"You ask me what they mean to do: upon my word, I don't know!" confessed the mayor, with a submission to the inevitable that was not without dignity. "Perhaps they merely wanted to frighten us . . . I hope so, but one can never be sure of anything with those fellows!"

Just then, a great commotion was heard in the street, accompanied by shouting and swearing. It was as though they were dragging a lorry to the door of the Black Sun. Those inside could distinctly hear the sound of shutters clapping against the walls of the houses opposite and Siméon's loud voice ringing through the echoing night:

"Hi, you, up there! Hide your ugly mugs, or I'll pepper them with lead."

The threat was no sooner uttered than it was followed by the report of a gun which woke up the whole village.

The needlewomen fell on their knees. Mme. Mûre and Mlle. Franchet, who were regular church-goers, began a Hail Mary. The sounds from outside bore evidence that the whole of the Rue Neuve was in an uproar; but the windows half-opened by the terror-stricken onlookers must have been closed again at once, for the threats of the Three Brothers had ceased. Nothing was now heard but the movement of their heavy shoes over the cobbles of the road and up and down the pavement. What were they doing? That was what all the people inside the inn were wondering. All were sweating with anguish and trembling with despair. However, the notary and the chemist, assisted by the mayor, the Roubions and some of the women, had made a last heroic effort and pushed the billiard-table against the door leading to the archway, through which they dreaded to see the ill-favoured features of one of the Vautrins appear at any moment. They worked thus for the general safety without making any demands upon Dr. Honorat, who had lost the last shred of resemblance to anything human and who sat huddled in a chair, in a corner, like a lifeless thing. All of them gave him a malevolent look as they passed and controlled themselves so as not to load him with insults. The chemist's wife, who was braver than the others, because of her adventure in the cavalry, manifested the general feeling towards the wretched doctor by spitting on the floor in his direction. Mme. Jules had caught the contagion of Mme. Roubion's tears. The sobbing of these two, combined with the mumbled prayers of the others, ended by irritating the mayor, who was pricking up his ears to try and discover what was happening in the street. Taking the name of the Lord in vain, he swore at them to stop; and, having thus restored silence, he put a chair on a table and scrambled up to peep through the fanlight above the window-shutters. From here, he was able to look into the street. What he saw, by the flickering flame of the lamp that was supposed to light that corner of Saint-Martin-des-Bois, seemed to fill him with fresh terror, for he was unable to control an excla mation which increased the excitement of the besieged.

He disregarded their requests for explanations and sprang from the chair to the table and thence to the floor with the nimbleness and agility of a youth of twenty:

"Oh no!" he cried. "We can't have that!"

"What? What?"

"We can't have that! We can't have that! Let me be, all of you, and hold your tongues!" This with a terrible oath. "No, we can't have that! . . . Keep quiet, keep quiet, will you? I must go and talk to them."

And, pushing aside the woebegone wretches who pressed round him, he leant against the bar-room door that opened on the Rue Neuve and glued his ear to it, after giving three great thumps on the shutter with his clenched fist:

"Hullo, you, out there!" he shouted. "What are you doing?"

The noise outside ceased as had that indoors.

The mayor resumed his position and called the Three Brothers by their names. Then some one was heard approaching the shutter from the street.

"Who's there?" asked the mayor.

"It's Hubert," said a voice.

"I'm the mayor speaking."

"What can I do for you, M. Jules?"

"What are you doing out there, in the street and at the corner of the square?"

"We're putting down some straw, Mr. Mayor, some nice, dry straw, which looked like spoiling in the Delarbres' loft."

"What for?"

"To send you to blazes, Mr. Mayor, since you refuse to hand over that old Honorat."

At the announcement of this fresh and imminent catastrophe, the cries were renewed in the bar-room of the inn. A fierce gesture of the mayor's demanded silence.

"You wouldn't do that, Hubert. You wouldn't do a thing like that . . . Oh, he's not answering! Shut up, all of you, can't you! . . . Hubert! . . . Hubert! . . . "

"What is it, Mr. Mayor?"

"You surely won't do that?"

"Oh, won't I just! Here, Zoé, give me the matches . . . "

Fresh cries, fresh roars in the bar-room.

"Hold, your blasted tongues, will you? . . . Hubert! . . . Hubert! . . . You can't do that . . . There are women in here, women and girls! . . . "

The last word referred to Mlle. Franchet, who would never see fifty-five again. But Hubert's tremendous voice now filled the whole street. Men have since said that it was heard from one end of the village to the other.

"We don't care a hang about the women. It's Dr. Honorat we want . . . "

Then, pushing his mouth against the door, he sent a hideous threat through the key-hole:

"You shall all go through the mill --- the notary and the chemist and the notary's wife and the chemist's wife --- if you don't hand Dr. Honorat out to us . . . Give us Honorat and all will be forgiven and forgotten . . . "

This time, the ruffian was so near that there was no mistaking what he said. It seemed to Sagnier and Valentin as though his voice were drilling the words of temptation into their ears. At the same moment, a great flame lit up the fan-light; fear and cowardice began to do their work; and the two men made a rush for the limp rag of a doctor huddled in his corner. And they had no difficulty in dragging with them the women, who were already raving at the thought of being burnt alive.