Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Volume 8092

Tarzan and the "Psychology of

Truth"

by Alan Hanson

“Tarzan

remained silent. He would not promise, and so he did not speak.”

The

truth, though, is that

Tarzan did lie

occasionally. Certainly, he did not do so as often as the average man,

but he

was not above employing strategic falsehoods when useful in what he

considered

to be noble causes. Before pointing out some examples of Tarzan’s lies,

let’s

set a couple of ground rules. First, let’s allow that Tarzan was

incapable of

lying prior to learning to speak human language. In March 1909, at the

age of

20, Tarzan, who had taught himself to read, wrote a note to Paul

D’Arnot, asking

him to “teach me the language of men.”

Tarzan quickly picked up both

French and

English, making him then vulnerable to the sin of telling lies.

Second,

for a statement to be a

lie, not

only does what the speaker said must

be untrue, but he must also know that

it’s untrue. At times Tarzan made statements that he thought were true

at the

time, but later proved to be false. Being mistaken does not make one a

liar.

Tarzan’s First Lie?

In

the closing pages of Tarzan of Apes, the ape-man,

standing in

a railroad waiting room, read a cablegram from his friend Paul D’Arnot

in

Paris. It read, “Finger prints prove

you Greystoke, Congratulations.”

Later,

William Clayton asked Tarzan, “If

it’s any of my business, how the

devil did

you get into that bally jungle?”

We

can excuse a lie at times if

it is said

to spare someone from learning a painful truth, and that could have

been one of

those times. However, it is possible that, despite the cablegram,

Tarzan still

believed at the time that his mother was an ape. He had dismissed

D’Arnot’s

previous assertions that the dead John and Alice Greystoke must have

been his

parents, and, after just a few months in civilization, Tarzan easily

could have

given no credence to a new forensic science like fingerprint

identification. So

it’s possible that he believed the statement he made at the end of Tarzan of the Apes was true.

Deceiving

Natives

Tarzan’s

first bona fide lie

occurs in The Beasts of Tarzan. While the

ape-man

was pursuing the villainous Nicholas Rokoff, he came upon a native

village. He

wanted to question its inhabitants concerning the white men he was

pursuing,

but he “was at a loss as to how he

might enter into communication with

these people

without either frightening them or arousing their savage love of

battle.” So,

he came up with a plan. He climbed into a tree hanging above the

village and

made sounds like a panther. Then he descended and hustled around to the

village

gates. There he yelled out to the scared natives within that he would

drive the

panther away if they would let him in the village and answer his

questions.

When the natives required that he drive the menacing cat away first,

Tarzan

returned to the tree, and, with great commotion and screams, pretended

to chase

the panther away. He then returned to the village gates and voiced an

obvious

lie: “I have driven Sheeta away. Now

come and admit me as you promised.”

No

harm, no foul, one might

say, but it was

certainly a lie, told to deceive fearful natives whom Tarzan knew would

believe

it. In ERB’s Tarzan stories there are several other incidents in which

the

ape-man purposely took advantage of fearful natives by lying to them.

One

example occurs in Tarzan and the Golden Lion. With a

woman under his

protection,

Tarzan entered a native village in a valley behind Opar. “I am going to

bring

my mate into your village and you are going to hide her, and feed her,

and

protect her until I return,” he told the scared natives. It was

a lie

when he

referred to the woman accompanying him as his “mate.” In fact, it was

not Jane,

but rather La, Queen of Opar. ERB explained why Tarzan felt the need to

tell

this particular fib.

“He

had thought it best to describe La as his mate, since thus they might

understand that she was under his protection, and if they felt either

gratitude

or fear toward him, La would be safer.”

Okay,

it was a harmless, little

lie, but

nevertheless, it was a lie, again challenging the notion that Tarzan

“never

lied.”

Tarzan

also lied to natives on

other

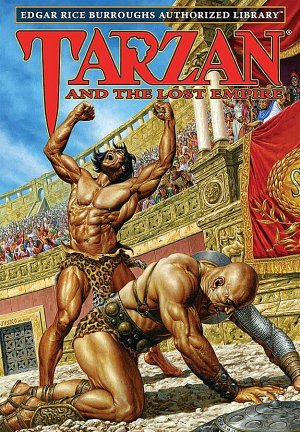

occasions. In Tarzan and the Lost Empire,

the ape-man again took advantage of superstitious natives by stretching

the

truth. After Tarzan had been captured and left bound in a hut, Nkima

dropped in

for a visit. When the native sentry asked Tarzan to whom he was

talking, the

ape-man replied, “That was the ghost

of your grandfather. He came to

tell me

that you and your wives and all your children would take sick and die

if

anything happens to me.”

In

Tarzan’s

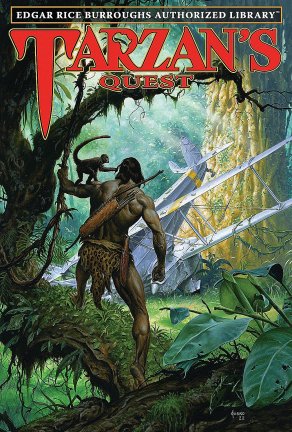

Quest, the ape-man lied

again to take advantage of fearful natives.

Pretending to be a member of a tribe of white savages who abducted

native

women, Tarzan threatened a scared native, “One sound and you die; I am

a

Kavru.” (The Kavru were a savage white tribe whose warriors

stole

native

girls.)

In

Tarzan

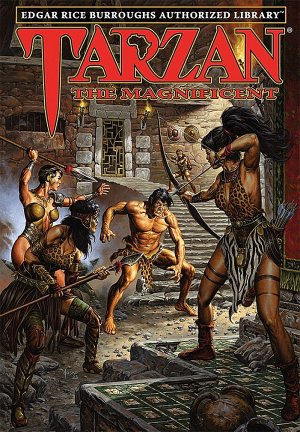

the Magnificent, the

ape-man again lied about his identify,

pretending to

be an evil spirit.

“Instantly

a head was thrust from an open window and a man’s voice demanded, ‘What

are you

doing there? Who are you?’”

“‘I

am Daimon,’ replied Tarzan in a husky whisper. Instantly the head was

withdrawn

and the window slammed shut. Tarzan, quick witted, had profited by

something

that Gemnon had told him — that the Athneans believed in a bad spirit

that was

abroad at night seeking whom it might kill. To Daimon they attributed

all

unexplained deaths, especially those that occurred at night.”

Deceiving Meriem

In

The

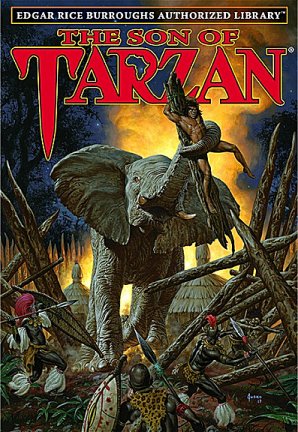

Son of Tarzan, the ape-man lied to Meriem, his future

daughter-in-law, when

he found her wandering in the wild. When she insisted on searching for

someone

she called “Korak,” Tarzan

promised to help her. “I shall not harm

you,” he

told her. “I only wish to discover if

you have fever … If you are well

we will

set forth in search of Korak.” It was a lie. Tarzan never

intended to

search

for the mysterious “Korak,” but instead wanted to lead Meriem to his

African

home.

“By

degrees he turned the direction of their way more and more eastward,

and

greatly was he pleased to note that the girl failed to note any change

was

being made … On the fifth day they came suddenly upon a great plain and

from

the edge of the forest the girl saw in the distance fenced fields and

many

buildings. At the sight she drew back in astonishment. ‘Where are we?’

she

asked, pointing. ‘We could not find Korak,’ replied the man, ‘and as

our way

led near my douar I have brought you here to wait and rest with my wife

until

my men can find your ape or he finds you.’”

The Son of

a God

All

of those lies told by

Tarzan were trifles

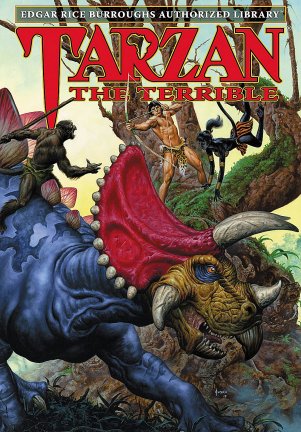

compared to the colossal lie the ape-man told and perpetuated in Tarzan the Terrible. In search of

his

missing wife, Tarzan boldly and openly walked into the Pal-ul-don city

of A-lur

and announced he had just arrived from heaven. “I come neither as a

slave nor

an enemy; I come directly from Jad-ben-Otho.” Escorted to the

king’s

palace, Tarzan

repeated the colossal assertion. “I

have come from the country of

Jad-ben-Otho

… Take me to the king at once lest the wrath of Jad-ben-Otho fall upon

you.”

When

a guard reached out to

grab an arm,

Tarzan doubled-down on his big lie. “Stop!”

he cried, “who would dare

touch the

sacred person of the messenger of Jad-ben-Otho? Only as a special mark

of favor

from Jad-ben-Otho may even Ko-tan himself receive this honor from me.

Hasten!

Already now have I waited too long! What manner of reception the Ho-don

of

A-lur would extend to the son of my father!”

The

son of their god! As

audacious was that

escalation of Tarzan’s big lie, ERB explained that the ape-man had

actually

considered claiming he was the top deity himself. “At first Tarzan had

been

inclined to adopt the role of Jad-ben-Otho but it occurred to him that

it might

prove embarrassing … it had suddenly occurred to him that the authority

of the

son of Jad-ben-Otho would be far greater than that of an ordinary

messenger of

a god.”

Tarzan

continued to build upon

his tall

tale.

“You

know the power of Jad-ben-Otho; how his lightnings gleaming out of the

sky

carry death as he wills it; how the rains come at his biddings, and the

fruits

and berries and the grains, the grass, the trees, and the flowers

spring to

life at his direction; you have witnessed birth and death, and those

who honor

their god honor him because he controls these things. How would it fare

then

with an imposter who claimed to be the son of this all-powerful god?

This then

is all the proof that you require, for as he would strike you down

should you

deny me, so would he strike down one who wrongfully claimed kingship

with him.”

Tarzan

brazenly kept adding

layers to his

fictitious claims. He insisted that “none

may sit upon a level with the

gods,”

(meaning him) in the temple and he informed Lu-don, the high priest,

“that the

blood of a false priest upon the altar of his temple is not displeasing

in the

eyes of Jad-ben-Otho.”

Later

Tarzan tried to use his

self-exalted

status in A-lur to soften the strict tenants of A-lur’s long-standing

religion.

“There

is but one god, and he is the god of the Waz-don as well as of the

Ho-don; of

the birds and the beasts and the flowers and of everything that grows

upon the

earth or beneath the waters. If Pan-at-lee (a slave) does right she is

greater

in the eyes of Jad-ben-Otho than would be the daughter of Ko-tan should

she do

wrong.”

Even

after Korak arrived to

save his

parents’ lives in the temple at A-lur, Tarzan continued to claim he was

the son

of their god. When Ja-don, A-lur’s new leader, asked Tarzan to transmit

to his

people the wishes of his father, Tarzan, still pretending to be the son

of

their god, responded.

“Your

problem is a simple one if you but wish

to do that which shall be pleasing in the eyes of god. Your priests, to

increase their power, have taught you that Jad-ben-Otho is a cruel god;

that

his eyes love to dwell upon blood and upon suffering. But the falsity

of their

teachings has been demonstrated to you today in the utter defeat of the

priesthood.

“Take

then the temples from the men and give them instead to the women that

they may

be administered in kindness and charity and love. Wash the blood from

your

eastern altar and drain forever the water from the western.

“Once

I gave Lu-don the opportunity to do these things but he ignored my

commands,

and again is the corridor of sacrifice filled with its victims.

Liberate these

from every temple in Pal-ul-don. Bring offerings of such gifts as your

people

like and place them upon the altars of your god. And there he will

bless them

and the priestesses of Jad-ben-Otho can distribute them among those who

need

them most.”

When

Tarzan, Jane, and their

son soon left

A-lur and Pal-ul-don, they left behind a new religion based upon a

framework of

falsehoods Tarzan had spread among the people. The people of A-lur in

Pal-ul-don would forever see the image of Tarzan of the Apes when they

imagined

the son of their god.

“The

king and many warriors and a multitude of people accompanied them

beyond the

limits of A-lur and after they had bid them good-bye and Tarzan had

invoked the

blessings of God upon them the three Europeans saw their simple, loyal

friends

prostrate in the dust behind them until the cavalcade had wound out of

the city

and disappeared among the trees of the nearby forest.”

The Forest

God of Chichen Itza

In

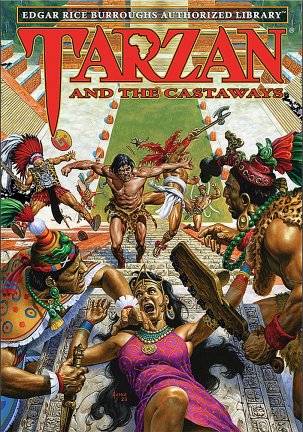

Tarzan

and the Castaways the ape-man one-upped his false caricature as

the

son of

a god in Tarzan the Terrible. The

ape-man told his most audacious and final lie, when he declared himself

Che,

Lord Forest, an actual god who came to earth in mortal form. As had the

people

of A-lur, the population of Chichen Itza bought into Tarzan’s false

claims just

because he was able to swim around in a volcano lake from dawn until

noon

without drowning. When Tarzan arose from the water, “the people fell to

their

knees before him and supplicated him for forgiveness and for favors.”

“I came to earth in the form of

a mortal,”

he told them, “to see how you ruled

my people of Chichen Itza. I shall

come

again someday to see if you have improved. Now I go.” As he rode

Tantor

into

the forest, Tarzan turned to see the people of Chichen Itza knelling

with their

faces pressed down. An English woman who witnessed the scene predicted,

“Their

great-great-grandchildren will hear of this.”

After

describing how Tarzan

reduced a white

African guide to subservience in Tarzan

and the Champion, ERB added the following observation about

Tarzan.

Tarzan’s

inherent “psychology

of the truth”

told him he could spread falsehoods if he knew the people who heard

them wanted

to believe they were true, and if they then led to successful action.

The lies

he told natives achieved both goals, as did the lie he told Meriem.

Certainly,

the lies he told the people of A-lur and Chichen Itza were welcomed by

the

population and resulted in positive changes in those societies for

generations

to come.

THE END

ERB, Inc. Authorized

Editions

https://www.ERBzine.com/craft

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® John Carter® Priness of Mars®

are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2025 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the

respective

owner.