The Lad and the Lion

(Written:

February-March 1914)

<>

<>Royal automobiles come and go

often in this

story about intrigue in a mythical European kingdom. After his father

was

assassinated, his grandson and apparent heir to the throne, was

spirited from

the palace in one of the “royal motors” and transported out of the

kingdom for

his protection. <> Count Sarnya,

previously one of

the king’s

closest counselors, then took precautions to protect himself.<>

“Ordinarily

he left by the postern door, but today he had order one of the palace

motors to

meet him inside the gates. His own car and police guard waited at the

postern

gate. Count Sarnya was keeping a rendezvous that he did not wish even

his own

police to know about.”

<>Ten years later,

Ferdinand, son

of the

kingdom’s puppet king, used the “royal motors” to help him carry on an

affair

with Hilda de Groot, the daughter of royal gardener. Hans de Groot knew

Ferdinand was taking advantage of his sister.

<>“He

saw a girl and two men enter a limousine and drive away. The girl was

Hilda,

and one of the men was Ferdinand … The car stopped in the city and

picked up

the pretty daughter of a cobbler; then it drove on out into the country

to the

hunting lodge in the woods.”

<>Eventually, Hilda’s

method of

transportation made people start to wonder how her family could afford

it.

<><>“When

people saw Hilda come home for a visit with her mother, as she did when

her

father was away, they would have thought Martin de Groot must be making

a great

deal of money; for Hilda rode in a beautiful English car with a

chauffeur and

footman.”

The

affair became public after

King Otto was

assassinated and Ferdinand became king.

“Hilda had two new motors and

many

magnificent jewels.” She didn’t enjoy driving her cars, however. “When

I drove

today, some people hissed at me; when I passed the cemetery, I saw a

man

digging a grave.” The sight was prophetic. The next car Hilda

rode in

was a

hearse.

<>

<>

<>

The

Man-eater

(Written:

May-June 1915)

<>

<>In The

Man-eater, Burroughs used an automobile in a most unusual way — as

the

setting for the story’s culminating action. Passing over the strange

circumstances that brought all the major characters together, the final

scene

opened one night with a chauffeur driving Mrs. Scott and her daughter

Virginia home

to the family’s Virginia mansion. A quarter mile from its destination,

the car

came to a stop. ERB, perhaps drawing from the breakdowns of his own

autos,

described how the chauffeur analyzed the problem.

“Getting

down from his seat and raising one side of the bonnet … he fussed about

between

the engine and the control board, trying first the starter and then the

horn.

‘Ah guess we-all blowed a fuse,’ he announced presently. ‘Have you

others, or

must we walk the rest of the way?’ inquired Mrs. Scott. ‘Oh, yasm, Ah

got some

right year,’ and he raised the cushion from the driver’s seat and

thrust his

hand into the box beneath. For a moment he fumbled about in search of

an extra

fuse plug.”

<>

<>As he clipped the new fuse plug

in place,

making the car ready to run again, the chauffeur noticed something

emerging

from the darkness and moving toward the car — a lion. The driver bolted

to the

side of the road, jumped a fence, and disappeared, leaving the two

women to

deal with the lion. Virginia considered their options."

“Should

she and her mother leave the machine and attempt to escape, or were

they safer

where they were? The lion could easily track them should he care to do

so after

they had left the car. On the other hand, the strange and unusual

vehicle might

be sufficient safeguard in itself to keep off a nervous jungle beast.”

<>Meanwhile, the lion

was

considering his

options as well.

“He did not like the looks of this

strange thing. What

was it?

He would investigate. The beast was beside the car now. Leisurely, he

placed a

forepaw on the running board and raised himself until his giant head

topped the

side of the tonneau.”

<>

<>Enter Dick Gordon,

courageous

hero. While

distracting the lion, he cried out asking Virginia if she knew how to

drive.

When she responded, “Yes,” Gordon commanded, “Then climb over and

drive. Drive

anywhere just as fast as you can.”

“The

girl clambered over into the driver’s seat and started the engine. With

the

whir of the starter (the lion) wheeled about with a low snarl, but in

an

instant the girl drew the speed lever back into low, pressed down on

the

accelerator, let in the clutch, and the car shot forward. Still the

lion seemed

in doubt. He took a few steps toward the car, which he could easily

reach in a

single bound.”

<>At that instant,

Gordon

distracted the

beast, allowing the two women to drive safely away.

<>

<>

<>

The Rider

(Written:

October-December 1915)

<>

<>In the European

principality of

Karlova,

the adventurous Prince Boris wanted to avoid an arranged marriage with

the

daughter of the King of nearby Margoth. His solution was to trade

places for a

week with the country’s notorious highwayman known as The Rider. The

outlaw,

dressed in the prince’s military uniform, rode in the first of many

automobiles

in the story. A French limousine carried him down a flower-strewn

boulevard into

Demia, the capital city of nearby Margoth. In the crowd along the

boulevard, the

real Prince Boris, incognito, met American Hemmington Main, who had

come to

Europe to track down love-interest Gwendolyn Bass, whose mother had

taken her

on a tour of Europe to keep Main from courting her daughter.

<>In one of those

wondrous

coincidences that

ERB used so much in his stories, Main just happened to spot the Bass

automobile

arriving in the city at the same time the Karlovian French limo drove

by.

<>

“An

automobile, a large touring car, honked noisily out of a side street

and

crossed toward the hotel entrance. Main chanced to be looking down into

the

street at the time. With an excited exclamation he half rose from his

chair.

‘There they are!’ he whispered. “The car drew up before the hotel and

stopped.

Two maids alighted, followed by a young girl and a white haired woman.”

Meanwhile,

Princess Mary of

Margoth decided

to avoid the supposed Prince of Karlova. “The open car, Stefan,” she

instructed

her aid. “The old one without the arms, and take me west on the Roman

road.”

Before leaving town, though, the princess decided to stop at the hotel

where

her American friend Gwendolyn Bass was staying.

<>Meanwhile, Prince

Boris,

incognito, hatched

a scheme to help Main hook up with Gwendolyn so that he could propose

to her.

Unfortunately, Boris wound up hijacking Princess Mary’s car instead of

the Bass

car, leading to multiple automobile scenes in the Margothian

countryside

through the remainder of the story. Below is one example.

<>

<>“Slowly

the big car wound its way up the steep grade. The gears, meshed in

second

speed, protested loudly, while the exhaust barked in sympathy through

an open

muffler. Stefan, outwardly calm, was inwardly boiling, as was the water

in the

radiator before him threatening to do. Silent, but none the less

sincere, were

the curses where with he cursed the fate which had compelled him to

drive “the

old car” up Vitza grade which the new car took in high with only a

gentle

purring.

<>“Almost

at the summit there is a curve about a projecting shoulder of rock, and

at this

point the grade is steepest. More and more slowly the old car moved

when it

reached this point — there came from the steel and aluminum lungs a few

consumptive coughs which racked the car from bumper to tail light, and

as

Stefan shifted quickly from second to low the wheels almost stopped,

and at the

same instant a horseman reined quickly into the center of the road

before them,

a leveled revolver pointing straight through the frail windshield at

the

unprotected breast of the astonished Stefan.

“One

single burst of speed and both horse and man would be ridden down. The

gears

were in low, the car was just at a standstill. Stefan pressed his foot

upon the

accelerator and let in the clutch. The car should have jumped forward

and

crushed the life from the presumptuous bandit; but it did nothing of

the sort.

Instead, it gave voice to a pitiful choking sound, and died.”

Hemmington

Main’s romantic

automobile-filled plans to find and marry Gwendolyn Bass were

successfully

concluded at the story’s end.

<>

The Oakdale Affair

January-June, 1917

<>

<>In ERB’s chronologically

challenged novella,

The Oakdale Affair, the initial event

in the three-day storyline is first revealed halfway through the second

chapter/

<> <>“Reginald

Paynter was dead. His body had been found beside the road just outside

the city

limits at midnight by a party of automobilists returning from a fishing

trip.

The skull was crushed back of the left ear. The position of the body,

as well

as the marks in the road beside it indicated that the man had been

hurled from

a rapidly moving automobile.”

<>

<>That same evening,

Abigail

Prim, the

“spinster” 19-year-old daughter of Oakdale’s prominent banker,

disappeared from

her parents’ home. The town’s citizens viewed the two events as somehow

interlinked, since Abigail and Reginald were old friends. On frequent

occasions

she had “ridden abroad in Reginald’s French roadster.” That evening,

though,

Abigail was not with Reginald. Instead, in a desperate attempt to

escape her

dreary life, she had stuffed her pockets with cash, disguised herself

as a boy,

and headed out into the adventurous world claiming to be the criminal

“Oskaloosa

Kid.” After teaming up with the philosophical drifter, Bridge, the two

witnessed a scary automobile incident.

“Bridge,

turning, saw a brilliant light flaring through the night above the

crest of the

hill they had just topped in their descent into the small valley, where

stood

the crumbling house of Squibbs. The purr of a rapidly moving motor rose

above

the rain … As the car swung onto the straight road before the house a

flash of

lightning revealed dimly the outlines of a rapidly moving touring car

with

lowered top. Just as the machine came opposite the Squibbs’ gate a

woman’s

scream mingled with the report of a pistol from the tonneau and the

watchers

upon the verandah saws a dark hulk hurled from the car, which sped on

with

undiminished speed, climbed the hill beyond and disappeared from view.

Bridge

started on a run toward the gateway, followed by the frightened Kid. In

the

ditch beside the road they found in a disheveled heap the body of a

young

woman.”

The

young woman, Hettie

Penning, survived

and joined an aggregate of characters shuffled back-and-forth

throughout the

night in various automobiles between the towns of Oakdale and Payton.

Passengers

in the crowded cars included Bridge, Abigail Prim (disguised as the

“Oskaloosa

Kid”), a gang of felonious hoboes (Dopey Charlie, Soup Face, Sky Pilot,

and The

General), Abigail’s father, Chicago Detective Dick Burton, half a dozen

sheriff

deputies, and a dozen carloads of indignant citizens looking for a

lynching.

Eventually, Miss Penning explained how some Oakdale lowlifes killed

Reginald

Paynter and threw his body out of their speeding car shortly before

they tried

to do the same to her. Other than Reginald’s “French roadster,” the

only other

specific type of car mentioned in The

Oakdale Affair is the large “touring car” used by Detective Burton

and his crew

of Chicago cops.

<>

Tarzan

the Untamed

(Written: August 1918–September

1919)

Only

one automobile appears in Tarzan the Untamed, and for

this one,

ERB specified the make. While British Colonel Capell and Lieutenant

Thompson

discussed a rescue mission to find a British pilot missing in West

Africa, “a

big Vauxhall drew up in front of the headquarters of the Second

Rhodesians.” The

vehicle carried British General Smut to a conference with Colonel

Capell.

Vauxhall Motors was then, and still is, a British maker of motor

vehicles.

<>

The

Efficiency Expert

(Written:

Sept.-Oct. 1919)

In

the summer of 1915, a flat

tire and a

beautiful woman gave Jimmy Torrance the self-esteem boost he needed to

continue

trying to make something of himself in Chicago.

The left front tire of Miss Elizabeth Compton’s car was flat.

Burroughs

explained, “There was an extra wheel on the rear of the roadster, but

it was

heavy and cumbersome, and the girl knew from experience what a dirty

job

changing a wheel is. She had just about decided to drive home on the

rim when a

young man crossed the walk from Erie Street.” Jimmy asked if he could

help her.

“It looks like a new casing,” he observed. “It would be too bad to ruin

it. If

you have a spare I will be very glad to change it for you.” After Miss

Compton

thanked him for changing the tire, Jimmy stood on the curb and watched

as she

drove away.

<>

<>Later in the story,

three

people, two cars,

and a motorcycle participate in a scene important to Jimmy Torrance’s

future.

It started when two taxis drew up side-by-side in front of a Chicago

roadhouse.

The Lizard, a pickpocket and safecracker, got out of one taxi and

joined Little

Eva, a lady of the evening, in the back seat of the other cab. Jimmy

had made

friends with both characters. After agreeing to get some “papers” that

would be

helpful to Jimmy, The Lizard got back in his cab, just as a motorcycle

policeman pulled up beside it. When The Lizard ordered the driver to

“Beat it,

bo!’ the taxicab leaped forward, accelerating rapidly. Also wanting to

avoid

the cops, Eva ordered her cab driver to, “Go on to Elmhurst, and then

come back

to the city on the St. Charles Road.”

<>

The Girl

From Hollywood

(Written:

November 1921–January 1922)

<>

<>Burroughs

characterization of

the youthful

Eva Pennington began with her impetuousness while driving a car.

“Now

the chauffeur was taking her bag and carrying it to the roadster that

she would

drive home along the wide, straight boulevard that crossed the valley —

utterly

ruining a number of perfectly good speed laws … The headlights of a

motor car

turned in at the driveway … With a rush the car topped the hill, swung

up the

driveway, and stopped at the corner of the house. A door flew open, and

the

girl leaped from the driver’s seat.”

<>

<>Her brother, Custer

Pennington,

also could

be careless behind the wheel, but for a different reason. When he had

been

drinking, he tended to swing “the roadster around the curves of the

driveway

leading down the hill a bit more rapidly than usual.” Custer next

appeared

driving the Pennington roadster in Los Angles. He had requested that it

be sent

to the city and parked in a garage for him to use the day he was

released from

jail. After first stopping to visit Grace Evans, a close family friend,

Custer

headed north to rejoin his family at their valley home.

<>

<>“Custer

found them waiting for him on the east porch as he drove up to the

ranch house.

The new freedom and the long drive over the beautiful highway through

the clear

April sunshine, with the green hills at his left and the lovely valley

spread

out upon his right hand, to some extent alleviated the depression that

had

followed the shock of his interview with Grace; and when he alighted

from the

car he seemed quite his normal self again.”

<>

<>After learning from

Custer

about his sister

Grace’s problems, Guy Evans’ drove along the same highway back to LA in

a

decidedly different state of mind<>.

“Guy Evans swept over the

broad, smooth

highway at a rate that would have won him ten days in the jail at Santa

Ana had

his course led him through that village … When he approached the

bungalow on

Circle Terrace, and saw a coupé standing at the curb, he guessed

at what it

portended; for though there were doubtless hundreds of similar cars in

the

city, there was that about this one which suggested the profession of

its

owner.” It belonged to a doctor.

<>After he learned

that movie

producer Wilson

Crumb had been the cause of Grace’s disgrace and death, Guy resolved to

kill

him. When Guy came upon Crumb standing by his broken down car one

evening, he

revenged his sister.

<>“He

rode to the mouth of Jackknife, and saw

the lights of Crumb’s car up near El Camino Largo … He rode up to where

Crumb

was attempting to crank his engine. Evidently the starter had failed to

work,

for Crumb was standing in front of the car, in the glare of the

headlights,

attempting to crank it. Guy accosted him, charged him with the murder

of Grace,

and shot him.”

<>

Marcia of the Doorstep

(Written:

April-October 1924)

<>

<>Edgar Rice

Burroughs revealed

his knowledge

of different makes and styles of automobiles in the text of Marcia

of the Doorstep, the only story

he wrote in 1924. For instance, listen to the conversation between

Marcia Sackett

and her fiancé as they enjoy a ride in the Steele Ford that his

father had

loaned him for the day.

<>“When we’re married,” Dick was saying,

“we’ll buy a classy little roadster like that maroon one that just

passed.”

<>

<>“Oh,

let’s have a Pierce,” cried Marcia, “it don’t cost any more to drive a

dream

Pierce than a dream Buick, and they are so much more satisfying.”

<>

<>“Why

not a Rolls-Royce, then?” he inquired.

<>"I

don’t care for foreign built cars,” the girl announced, as one who has

given a

subject much expert consideration.

<>“Oh,

wouldn’t it be great to be rich, Marcia,” he cried, “and be able to buy

any

kind of car you wanted?”

<>

You Lucky Girl!

(Written:

1927)

<>

<>While

no actual cars appear in

this play

that Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote for his daughter Joan, the plot is

based on

competition for obtaining two car dealerships in the Midwest city of

Millidge.

Bill Mason is a 29-year-old owner of a small garage and repair shop who

wants

to purchase a local agency to sell the new Gormley Six automobile. He’s

convinced it’s “going to be the biggest selling car in this country

inside of a

year.” Bill explains to his good friend Corrie West that,

unfortunately, he doesn’t

have the $10,000 needed to invest in the agency.

<>

<>Jumping forward three years in

the play,

the audience learns that Bill and his father have not only found the

money

somewhere to buy the Gormley Six agency, but also a second car

dealership. That

brings Bill into conflict with Phil Mattis, the well-healed son of the

town’s

banker.

<>

<>Phil to Bill: “Well,

listen. You succeeded in getting the agency for the Gormley Six

away from me last year. I don’t know how you did it, but you did it.

All right,

you won that time. I don’t know where you got the money and I’m not

asking. You

seem to have taken in a lot of new capital since your father resigned

at the

bank and went into business with you, but that is neither here nor

there. What

I am up here to see you about is the Packard agency. Your father knew

that I

wanted that and just today I had a wire from the factory saying that

they were

closing negotiations with another dealer here. I know that means you.”

Bill:

“You are correct.”

Phil:

“I

want that Packard agency and I want the Gormley Six back, too. I have

my own

reason for wanting them and I can afford to buy what I want. I have

come up

here to buy those two agencies.”

Bill:

“They

are not for sale.”

At

the end of the play, the

audience learns

where the money came from to finance Bill’s car dealerships. His father

tells

Bill that Corrie West, who had since become a successful actress,

provided the

needed money and thereby became a silent partner in Mason & Mason

Automobiles.

< style="font-weight: bold;">

Calling All Cars

(Written:

June 1931)

<>

<>The appearance of the word

“cars” in this

ERB short story tips the reader off that cars play a part in the plot.

The suspense

begins late one night when Maddox, a servant in a mansion on a

Hollywood

hilltop, hears the humming of gears, indicating “a car was coming up

the hill

in second.” Unsure about the reason any car would be climbing up the

hill road

at that time of night, Maddox called the police.z

“Presently

the car came in sight, grinding slowly up the grade. Maddox could see

that it

was a dark colored sedan and that there were two people in the front

seat. The

car drew directly into the curb in front of the house and stopped … As

they got

out of the car the light from a street lamp fell upon them, revealing a

hatless

young man in grey coat and white trousers. He was about five feet ten,

and his

companion, a young woman, was perhaps five inches shorter.”

Meanwhile,

Maddox’s call to the

police drew

a response.

“From far below them, somewhere out of that vast network of

city

streets, rose faintly the weird wail of a police siren. Gradually it

rose in

volume as the car raced west on Sunset Boulevard. Presently they caught

occasional glimpses of its red spotlight as it flashed by open spaces

in the

traffic. Like the hopeless plaint of a lost soul, its raucous screech

cleft the

night.”

<>The man and woman,

who had

reached the top

of the hill in the first car, leaned over a railing in front of the

mansion and

watched the police car approach.

<>“It

flashed into view on the visible stretches of the winding canyon road

below

them — a red-eyed demon of the night, appearing and disappearing as it

roared

its shrieking way around the innumerable curves and shoulders of the

ascent. With

an expiring wail the siren suddenly went dumb. The car drew into the

curb and

three officers leaped out. Two of them walked briskly toward the Gothic

entrance, the other remained by the car.”

It

turned out that the two cars

played minor

roles in the story’s plot. For Burroughs the two motor vehicles were

simply

“literary vehicles” to get the characters to the hilltop mansion, where

the

people in both cars became involved in solving a murder mystery.

<>

Pirate

Blood

(Written: February-May 1932)

<>

<>Johnny Lafitte, the

hero of Pirate Blood, tells the story in the

first person. Although he was a star athlete in college, Johnny was a

poor

student who couldn’t find a high-paying job after graduating. Early on

in the

story he worked as a police officer. Below he gives the details of a

particular

stop he made of a speeding driver.z

“I’d

been handing out tickets on the state highway just outside town until I

almost

had writer’s cramp. I was sitting on my machine in a little hide-out on

a side

road waiting for the next victim, when a great big, flashy roadster

with the

top down streaked by at about seventy … About the only people in town

who drove

cars like that were members of that country club. And I was right. The

car was

slowing down to make the turn into the entrance to the club grounds

when I

pulled up alongside and motioned it over to the side of the road.

<>“As I

left my machine and walked toward the side of the roadster I was

reaching into

my inside pocket for my book without looking up at the driver. When I

did, I

saw it was a girl (Daisy Juke) … I was leaning close to her, my heart

full of

love, she was a thousand miles away from me — the chassis of the car

she drove

cost sixteen thousand dollars without any body … She asked me to come

and see

her, and I promised that I would; then she started up and turned up the

driveway of the country club — where I could only go as a cop. I didn’t

write

any more tickets that day.”

<>

Tarzan

and the Lion Man

(Written:

February-May 1933)

<>

<>The storyline is

structured

around a

Hollywood studio’s expedition in Africa to obtain film scenes for use

in a

“jungle movie.” The actors and crew were sent to Africa with a fleet of

28

motor vehicles to film in the Ituri Forest. Included were a generator

truck,

two sound trucks, 20 five-ton supply trucks, and five passenger cars. ERB didn’t mention much about the 23 trucks,

but one of the cars had a role in the action. Burroughs didn’t mention

the make

or type of the cars, but they must have been heavy-duty vehicles to

manage the

off-road route taken by the expedition.

The

car seen most often in the

story is the

one carrying Naomi Madison, the film’s female lead, and Rhonda Terry,

her

stand-in. The girls’ hand baggage was in their car’s backseat and a

makeup bag was

upfront with them.

Three

times a flurry of arrows

was launched

at the film company by warriors of the Bansuto tribe. During the

attacks, Naomi

Madison screamed and crouched upon the floor of her car, even fainting

once.

Rhonda Terry, however, fought back. During the first attack, she stood

with

one foot on the running board, a pistol in her hand.

.” During the second

attack,

Rhonda stepped out of the car, joining the men in all the other cars

looking

for attackers to fire at.” During a third attack, the natives rushed

Naomi and

Rhonda’s car. Again, “Naomi Madison slipped to the floor of the car.”

As a

dozen men with rifles rushed to defend the girls, “Rhonda drew her

revolver and

fired into the faces of the onrushing blacks.” The film company finally

got the

footage it needed, and the five cars were part of the “long caravan” of

vehicles that Tarzan watched heading out of Africa and back to

Hollywood.

<>The final chapter

of Tarzan and the Lion Man finds Tarzan in Hollywood a

year

after the

events earlier in the story. The city’s environment, including its many

automobiles, depressed the ape-man.

<><>“He

saw many people riding in cars or walking on the cement sidewalks and

the

suggestion of innumerable people in the crowded, close built shops and

residences; and he felt more alone than he ever had before in all his

life.”

<>When a couple of

Hollywood

troublemakers

invited him to go to a party with them, the curious Tarzan agreed. He

thought

the circuitous route they were taking to the party seemed strange, but

he

didn’t realize he was about to crash a party with them.

<>“On a

side street near Franklin they climbed into a flashy roadster. Brouke

drove

west a few blocks on Franklin and then turned up a narrow street that

wound

into the hills. Presently they came to the end of the street. ‘Hell!’

muttered

Brouke and turned the car around. He turned into another street and

followed

that a few blocks; then he turned back toward Franklin. On a side

street in an

otherwise quiet neighborhood they sighted a brilliantly lighted house

in front

of which several cars were parked; laughter and the sounds of radio

music were

coming from an open window. ‘This looks like the place,’ said Reece.

‘It is,’

said Brouke with a grin, and drew up at the curb.”

When

he heard the sirens,

Tarzan decided

he’d forego riding back to town in a police car. Instead, he jumped out

an

upstairs window into a tree and disappeared.

<>

Tarzan

and the Lost Empire

(Written:

March-May 1928)

<>

<>A look back at a

humorous

reference to

contemporary automobiles is a good way to conclude this study of cars

in ERB’s

fiction. Since the “lost cities” that Tarzan encountered were

inevitably frozen

in time long before the internal combustion engine was invented, 20th

century automobiles were never found there. In fact, citizens of those

lost

cities couldn’t even conceive of modern cars, as Erich von Harben

discovered in

Tarzan and the Lost Empire.

<>

<>Obviously, there

were no

motorized vehicles

in Castrum Mare, a Roman city that had not advanced technologically in

the two

millennia since it was founded in a secluded location in Central

Africa.

However, Burroughs obviously had some fun when he had his 20th

century character, Erich von Harben, try to explain the characteristics

of the

modern automobile. During a conversation while he and Mallius Lepus

were riding

on a slave-carried litter, von Harben told his friend that many changes

had

occurred in modern Rome. Lepus responded,

“But certainly that could

have been

no great change in the style of litters, and I can’t believe that the

patricians have ceased to use them.” Von Harben then struggled to

describe

motorized vehicles to the incredulous Roman. Some excerpts from that

conversation:

Erich:

“Their

litters travel on wheels now.”

Mallius:

“Incredible!

It would be torture to bump over the rough pavement and

country roads on the great wooded wheels of ox-carts.”

Erich:

“The

city pavements are smooth today and the countryside is cut in all

directions by

wide, level highways over which the litters of the modern citizens of

Rome roll

at great speeds with small wheels with soft tires.”

Mallius:

“I

warrant you that there be no litters in all Rome that move at

greater speed than this … better than eighty-five hundred paces an

hour.”

Erich:

“Fifty

thousand paces an hour is nothing unusual for the wheeled litters of

today. We

call them automobiles.”

Mallius:

“You are

going to be a great success. Tell (the guests of Septimus

Favonius) that there be litter-carriers

in Rome today who can run fifty thousand paces in an hour and they will

acclaim

you the greatest entertainer as well as the great liar Castrum Mare has

ever

seen.”

Erich:

“I

never said that there were litter-bearers who could run fifty-thousand

paces an

hour.”

Mallius:

“But did

you not assure me that the litters traveled that fast? Perhaps

the litters of today are carried by horses. Where are the horses that

can run

fifty thousand paces in an hour?”

Erich:

“The

litters are neither carried nor drawn by horses or men, Mallius.”

Mallius:

“They fly

then, I presume. By Hercules, you must tell this all over

again to Septimus Favonius. I promise you that he will love you.”

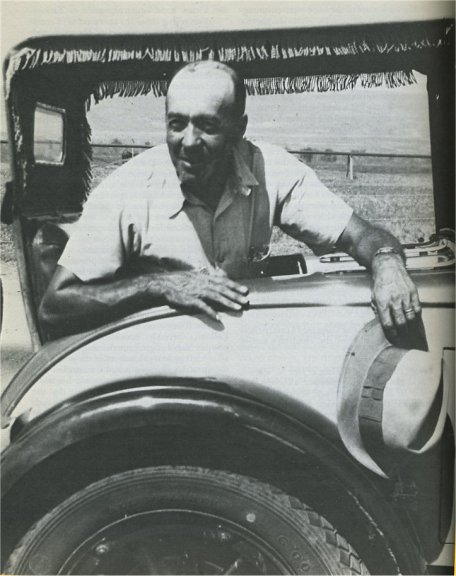

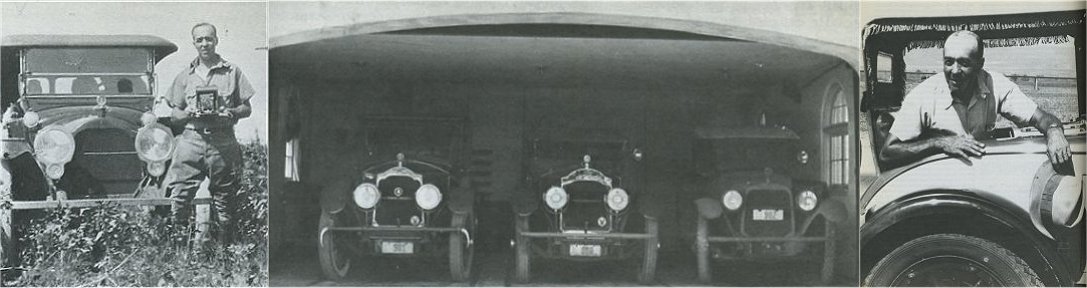

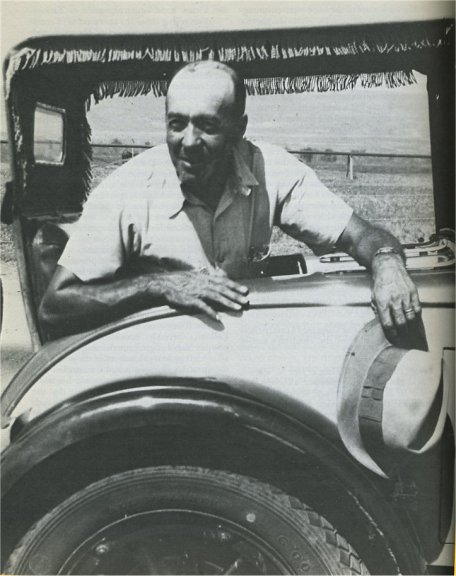

ERB poses with his new 1937 Packard on the docks at Vancouver, Canada.

In early October 1938, Burroughs and his wife sailed from

Honolulu to

Vancouver to pickup the new automobile waiting for them there.

In an article in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on October 7,

1938, ERB indicated that he and his wife

would "tour the coast" as they drove the new Packard to their home in

Southern California.

—

the end —