Volume 8090

<>

As

fascinated as Edgar Rice Burroughs was with automobiles throughout his

adult

life, it’s not surprising to find them scattered throughout the fiction

that he

produced during his adult life. He even designed some interesting

extra-terrestrial vehicles for use by alien races in his Mars and Venus

tales,

but let’s put them aside for now, and examine the motor vehicles he

used in his

stories set on Earth.

First,

a vocabulary lesson on the terminology that ERB utilized. He often used

“automobile” and “car,” terms commonly in use today. However, he also

used

another term, outdated now, to refer to all cars, particularly in his

early

stories. At one point in the second part of The

Mad King, written in 1914, Barney Custer revealed what he found

in a nearby

building. “It’s a machine,” he

whispered to his companion, who then understood that Barney had found

an

automobile.

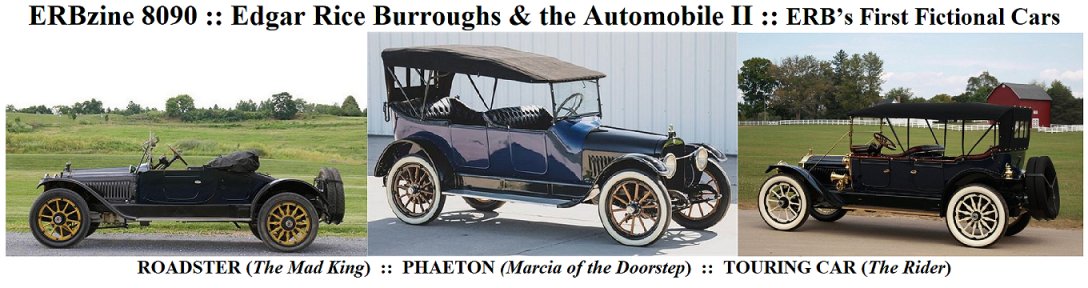

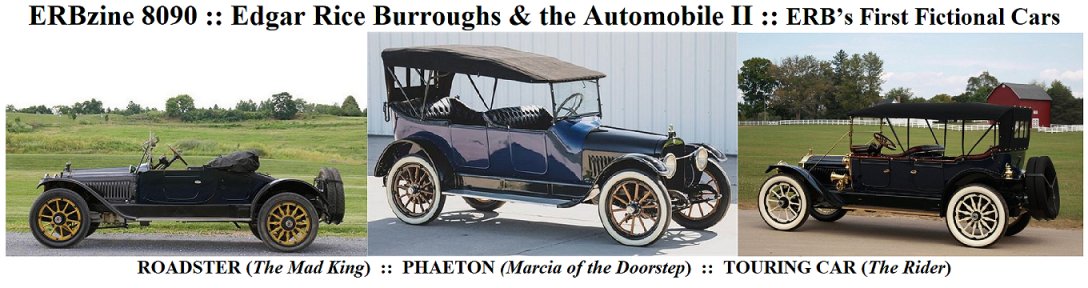

ERB

identified that specific car as a roadster,

another term seldom used today. Initially it was an American term for a

two-seat car with no weather protection. The model evolved over the

years to

included two-seat convertibles. Another early car model Burroughs

mentioned was

a phaeton. Like a roadster, a phaeton lacked any fixed weather

protection, but had a back seat to carry passengers. In Marcia of the Doorstep, written in

1924, family patriarch Marcus

Aurelius purchased a new car. Its initial outing with the family aboard

ended

sadly.

“There

was a crash, a volley of profanity, a couple of screams from the back

seat and

Marcus Aurelius’ new sport model phaeton was merged with a yellow taxi.”

A

vehicle model mentioned more often by ERB is the touring car. It was a popular American

family style of open car

seating four or more people. It was popular in the early 1900s and

1920s. In

ERB’s story The Rider, the Bass

family packed into a “large touring car” for a planned European tour.

Keeping

those terms in mind, let’s look at some of the ways ERB utilized cars

in some

of his earliest stories. Since Burroughs first novel was set on Mars

and his

second was about events that took place on earth in the Middle Ages, it

wasn’t

until his third, and most famous novel, that automobiles first played a

part in

his fiction. (The period during which Burroughs wrote each story is

listed

below the story’s title.)

Dec. 1911 – May 1912

In

the final two chapters of Tarzan of

the

Apes, the notable characters shuttle around in three different

automobiles.

To keep them straight, let’s call them the “Clayton Car,” the “Canler

Car,” and

the “Tarzan Car.” The first to appear is the “Clayton Car,” which, with

its

owner, William Clayton and family friend Mr. Philander, was waiting at

the

train station in Wisconsin when Jane, her father, and Esmeralda

arrived. They

all piled into the “Clayton Car,” which then “quickly whirled away

through the

dense northern woods toward the little farm” that Jane had inherited

from her

mother.

A

week later, the “Canler Car,” “a purring six cylinder,” pulled up to

the

farmhouse. The driver, Robert Canler, had come to demand that Jane

marry him as

promised. After she finally gave in, Canler drove away the next morning

to get

a marriage license and a minister.

While

Canler was gone, a fourth automobile, a great black car, came careening

down

the road and stopped with a jolt at the cottage. It was Tarzan, of

course, come

to rescue the whole crowd from an approaching forest fire. When he

learned Jane

was off walking in the woods, he ordered Clayton to put everybody else

in his

car and drive them to safety by the north road. “Leave my car here,”

Tarzan

directed. “If I find Miss Porter we

shall need it.” The rest of the party then

climbed in the “Clayton Car” and he drove them off to safety.

Meanwhile, with

the ape-man at the wheel, the “Tarzan Car” drove toward the fire to

find and

rescue Jane. With her in the car, Tarzan sped toward safety. “The car was

plunging along the uneven road at a reckless pace,” Burroughs

noted. When the

danger had passed, Tarzan slowed the car down. It was in that vehicle

at that

time that Tarzan offered Jane his love and asked for hers.

Before

she could answer definitely, they arrived at a little hamlet where they

found

Clayton and his passengers standing around the “Clayton Car.” They were

all

sitting in the parlor of a little hostelry, when “the distant chugging of an

approaching automobile caught their attention.” It was the

“Canler Car”

returning with a minister to solemnize the driver’s marriage to Jane.

Canler

was only in the hostelry for a few moments before Tarzan “convinced”

him to

drive away in his car.

The

remaining group went outside and got into the two cars — Clayton, Jane,

her

father, and Esmeralda in the “Clayton Car” and Mr. Philander with the

ape-man

in the “Tarzan Car.” Mr. Philander spoke to the silent driver. “Bless

me,” he

said, “Who would ever have thought

it possible! The last time I saw you you

were a veritable wild man, skipping about among the branches of a

tropical

African forest, and now you are driving me along a Wisconsin road in a

French

automobile.”

Meanwhile,

ahead in the “Clayton Car,” a confused Jane Porter made a fateful

mistake. She

convinced herself that life with Clayton would be preferable to life

with a

wild man. In the train station waiting room, she told Tarzan she had

agreed to

marry Clayton. Later, on the station platform, Tarzan renounced his

birthright.

Unable to face Clayton, Tarzan decided at the last minute to drive his

car back

to New York. Jane told Clayton it was because Tarzan was anxious to see

more of

America than is possible from a car window.

Two

automobiles play roles during the two months Tarzan lived in Paris at

the

beginning of The Return of Tarzan.

While out for a walk one night, Tarzan stood on the sidewalk of a

well-lighted

boulevard waiting for traffic to clear before crossing the street.

Burroughs

recounted the communication between him and a passenger in a passing

vehicle.

Tarzan

and Olga had met on the ocean liner that brought both of them back to

France

from America. Their passing encounter on a street in Paris that evening

set in

motion events that a month later led Tarzan to a potentially fatal ride

in

another automobile. On the morning of November 26, 1909, Tarzan climbed

into

Paul D’Arnot’s “great car” for a short drive to a field outside Paris.

Tarzan

went there to answer the challenge of Count de Coude for an incident

that

occurred in the boudoir of the count’s wife a few days before. Although

wounded

twice, Tarzan survived the duel, and after some discussion, the

opponents “rode

back to Paris together in D’Arnot’s car, the best of friends.”

Jan.-Feb., 1914

Nearly

three years and many adventures passed before another automobile played

a role

in Tarzan’s life. In September 1912, Lord Greystoke was in Paris

visiting

D’Arnot, when he received a telegram informing him that his infant son

had been

kidnapped in London earlier that day. Hurrying home, Tarzan was met by

a

“roadster” at the station and driven to his family’s London townhouse.

There he

learned the kidnapping details from his distraught wife. While the

baby’s nurse

was wheeling him along the sidewalk outside the Greystoke residence, a

taxicab

drew up at the corner ahead. Carl, new houseman, then lured the nurse

back

toward the house. When the nurse reached the townhouse door, she turned

to see the

man wheeling the buggy toward the corner.

“Leaping to

the running board, she

had attempted to snatch the baby from the arms of the stranger, and

here,

screaming and fighting, she had clung to her position after the taxicab

had got

underway; nor was it until the machine had passed the Greystoke

residence at a

good speed that Carl, with a heavy blow to her face, had succeeded in

knocking

her to the pavement.”

After

Lady Greystoke witnessed the nurse’s brave attempt, she also tried in

vain to

reach the passing vehicle. After Tarzan arrived home, a conspirator’s

phone

call lured him to Dover to retrieve his son. Lord Greystoke told his

wife to

stay home, but her fear for her son overcame his directive, and she had

her

chauffeur drive her to the station to catch the late train to Dover.

There both

Tarzan and Jane were shanghaied. No automobiles existed where they

spent the

next four months. They would not return to their London home until

January

1913.

July 1913 – March 1914

After

establishing himself as a successful writer of imaginative fiction, ERB

made

his first attempt at contemporary social fiction with The

Girl From Farris’s. Since the setting is Burroughs’ hometown of

Chicago, automobiles play a part in the storyline. The reader learns at

the end

of the story that, prior to the beginning of the story, the car of

Chicago

businessman John Secor stalled in front of the countryside homestead of

the

Lathrop family. While the chauffeur tinkered with the motor, Secor

knocked on

the Lathrops’ door and asked for a glass of water. Infatuated

immediately with

the widowed Mrs. Lathrop’s daughter June, Secor returned many times in

his

chauffeured automobile to visit her. After being convinced to marry

Secor, June

was driven into town in her new husband’s car and installed in a room

at

Farris’s, a Chicago brothel.

“I know a

gink right now that’ll

pass me out five hundred bones any time for a squab like you. Say the

word and

I’ll split with you … He’d set you up in a swell apartment, plaster

sparklers

all over you, and give you a year-after-next model eight-lunger and a

shuffer.

You’d be the only chesse on Mich. Boul.”

After

June declined the officer, Eddie gave her money to buy new clothes so

that she

could get a respectable job. Meanwhile, Ogden Secor, son of John, the

bigamist

who duped June, was engaged to Sophia Welles, a Chicago socialite,

whose father

had made “several fortunes in the automobile industry.”

Aug. 1913 – March 1916

Edgar

Rice Burroughs may have loved automobiles, but Billy Byrne, the

protagonist in The Mucker, decidedly did not. As a

young man growing up on Chicago’s East Side, Billy hated everything

that was

respectable. An expensive car was one of those things. “He had writhed in

torture at sight of every shiny, purring automobile that had ever

passed him with

its load of well-groomed men and women.”

Years

later, after escaping from police following a murder conviction, Billy

had

another reason for disliking automobiles. The Kansas City police

received a tip

that Billy was at a farmhouse outside the city. ERB noted, “It was but a little

past one o’clock that a touring car rolled south out of Kansas City

with

Detective Sergeant Flannagan in the front seat with the driver and two

burly

representatives of Missouri law in the back.” Billy and Bridge

were saying

good-bye to the woman at the farmhouse, when “the dust of a fast-moving

automobile appeared about a bend in the road a half-mile from the

house.”

Fortunately for Billy, the farmer’s wife hid the two hobos in her attic

before

the police car arrived.

Although Billy achieves respectability at the end of the story, he is never seen driving a car, a machine he had hated and feared all his life.

Oct.-Nov. 1913 / Sept.-Nov. 1914

Of

the hundreds of characters Edgar Rice Burroughs created, Barney Custer

of

Beatrice, Nebraska, drove the most cars. In The

Mad King, he appears behind the wheel of four automobiles, two that

he owned

and two that he stole. Barney is first seen paying a storekeeper for

gasoline

he had just purchased for his gray roadster. It was the fall of 1912,

and

Barney was visiting for the first time his mother’s native land, the

small

Balkan kingdom of Lutha. After leaving the hamlet of Tafelberg, he

drove

through the picturesque countryside. Burroughs then described the

incident that

his life changed forever.

“Just

before him was a long, heavy

grade, and as he took it with open muffler the chugging of his motor

drowned

the sound of hoof beats rapidly approaching behind him. It was not

until he

topped the grade that he heard anything unusual, and at the same

instant a girl

on horseback tore past him.”

Noticing

the girl’s horse was out of control, Barney pressed the accelerator,

and, “Like

a frightened deer the gray roadster sprang forward in pursuit.”

As the road was

narrow, Barney drove up the outside to prevent the horse from plunging

into the

ravine below. He was able to pull her off the horse and onto the car’s

running

board, but the roadster skidded though a tight turn in the road and

toppled

over into the ravine. Barney shoved the girl off the running board, but

he went

over the embankment with his car. Fortunately, he was thrown from the

vehicle

and landed unharmed in a bush. Much later in the story, the reader

learns that

Barney’s car actually landed on Leopold, the heir to the throne of

Lutha,

pinning him go the ground temporarily. He escaped before the car burst

into

flames.

The

girl Barney sacrificed his car to save was Emma Von der Tann, who later

became

his love interest in the story. After a series of typical Burroughsian

adventures, Barney left Lutha a month later and returned to his home in

Nebraska at the conclusion of part one of The

Mad King.

Nine

months passed before Barney’s second car appeared at the beginning of

part two.

After an agent by an enemy in Lutha failed in an attempt to kill Barney

in

Beatrice, Barney decided he must return to Lutha. While his new

roadster, which

Burroughs described as “a later

model of the one he had lost in Lutha,” was in

a Beatrice repair shop, Barney learned the assassin has fled to

Lincoln,

Nebraska. Without even saying good-bye to family, “he leaped into his gray

roadster … and the last that Beatrice, Nebraska, saw of him was a

whirling

cloud of dust as he raced north out of town toward Lincoln.” He

left his car there

and took a train to New York. He tracked the assassin across the ocean,

eventually making his way to Burgova, Austria-Hungary, in early August

1914.

Since World War I had broken out in the Balkans, the border with

neighboring

Lutha was closed.

Near

the headquarters of an Austrian army corps, “his eyes hung long and greedily

upon the great, high-powered machines that chugged or purred about him

… If he

could but be behind the wheel of such a car for an hour! The frontier

could not

be over fifty miles to the south … what would fifty miles be to one of

those

machines?” Clothed in the uniform of an Austrian corporal he had

killed, Barney

walked boldly to a “big, gray machine” left unattended in front of the

headquarters building.

“To crank

it and leap to the

driver’s seat required but a moment. The big car moved slowly forward.

A turn

of the steering wheel brought it around headed toward the wide gates.

Barney

shifted second speed, stepped on the accelerator and the cutout

simultaneously,

and … shot out of the courtyard. None who saw his departure could have

guessed

from the manner of it that the young man at the wheel of the gray car

was

stealing the machine.”

Outside

the town, Barney drove south down a country road with Austrian troops

marching

on both sides. He bluffed his way onto the open road toward the

frontier, and

at the border was waved through without comment by an Austrian customs

officer.

Barney

was bound for the castle of Prince Ludwig von der Tann, Prince of Lutha

and

father of Emma von der Tann. “He

flew through the familiar main street of the

quaint old village (Tafelberg) at a speed that was little, if any less,

than 50

miles an hour … On he raced toward the south, his speed often

necessarily

diminished upon the winding mountain roads, but for the most part

clinging to a

reckless mileage.” Half way to his destination, a patrol of

Austrian

infantrymen signaled him to pull over. Instead, he pressed the

accelerator

down. “At over sixty mils an hour

the huge, gray monster bored down upon them.

One of them fell beneath the wheels — two others were thrown high in

air as the

bumper struck them.”

“For a few

minutes he held to his

rapid pace before he looked around, and then it was to see two cars

heading

toward him in pursuit. Again he accelerated the speed of the car. The

road was

straight and level. Barney watched the road rushing rapidly out of

sight

beneath the gray fenders. He glanced occasionally at the speedometer.

Seventy-five miles an hour … He saw the needle vibrate up to eighty.

Gradually

he nursed her up and up to great speed … The needle rose steadily until

it

reached 90 miles an hour — and topped it.”

Then

the radiator, penetrated by a bullet fired at the roadblock, began to

hiss and expel

steam. “At the speed he was going it

would be but a short time before the

superheated pistons expanding in their cylinders would tear the motor

to

pieces. Barney felt that he would be lucky if he were not killed when

it

happened.” The sight ahead of a bridge over a river gave Barney

an idea.

“As he neared the bridge, he reduced speed to

15 miles an hour, and set the hand throttle to hold it there. Still

gripping

the steering wheel with one hand, he climbed over the left-hand door to

the

running board. As the front wheels of the car ran up onto the bridge,

Barney

gave the steering wheel a sudden turn to the right and jumped. The car

veered

toward the wood handrail (and) the big machine plunged through them

headforemost into the river. Barney ran across the bridge, leaped the

fence and

plunged into the shelter of the wood. Then he turned to look back up

the road

in the direction from which his pursuers were coming. They were not in

sight —

they had not seen his ruse. The water in the river was of sufficient

depth to

completely cover the car.”

After

hiding in the woods for week avoiding capture by Austrians, Barney just

happened to be in the right place at the right time to save Emma von

der Tann,

who was fleeing from abductors taking her to Blentz to be forcibly

married to

Peter. Looking for a way to reach the capital city of Ludstadt, the

couple came

upon a driveway outside a small town. “People

who build driveways into their

grounds usually have something to drive,” Barney said to Emma. “Whatever it is

it should be at the other end of the driveway. Let’s see if it will

carry two.”

In a garage, Barney found a roadster. “He

ran his hand over the pedals and

levers, breathing a sigh of relief as his touch revealed the familiar

control

of a standard make.” For the second time in less than a week,

Barney became a

car thief. “It’s the through express

for Lustadt and makes no stops for

passengers or freight,” he joked with Emma.

Soon,

though, they heard the sound of horses on the roadway behind them.

Barney

increased the speed of the car, but the road was heavy with sand, and

ruts

gripping the tires slowed the speed. They held the lead for a mile. “She’s

reached her limit in this sand, and there’s a grade just ahead,” Barney

lamented. “We may find better going beyond, but they’re bound to gain

on us

before we reach the top.” An excited Emma responded, “I know where we

are now.

The hill ahead is sandy, and there is a quarter of a mile of sand

beyond, but

then we strike the Lustadt highway, and if we can reach it ahead of

them their

horses will have to go ninety miles an hour to catch us.”

“They

had reached the grade at last, and the motor was straining to the

Herculean

task imposed upon it. Grinding and grating in the second speed the car

toiled

upward through the clinging sand. The pace was snail-like. Behind, the

horsemen

were gaining rapidly … The top of the ascent lay but a few yards ahead,

and the

pursuers were but a few yards behind.” Emma turned and fired three

shots at

their pursuers. Then the car topped the hill and sped forward downhill

through

the last quarter-mile of sand toward the good road ahead.

“At last

the white ribbon of the

main road became visible. To the right they saw the headlights of a

machine.

But the machine was a mile away and could not possibly reach the

intersection

of the two roads before they had turned to the left toward Lustadt.

Then the

incident would resolve itself into a simple test of speed between the

two cars

— and the ability and nerve of the drivers. Barney hadn’t the slightest

doubt

now as to the outcome. His borrowed car was a good one, in good

condition. And

in the matter of driving he rather prided himself that he needn’t take

his hat

off to anyone when it came to ability and nerve.”

Suddenly,

from the engine came a “sickly, sucking sputter,” and the car slowed

down. The

engine shut down, and the two passengers sat in silence as their

“machine”

coasted to a stop. It was out of gasoline. When their pursuers arrived

they

found Barney and Emma standing beside the worthless car. Peter’s

soldiers took

them into custody.

That was

the fourth and last

“machine” that Barney Custer drove in ERB’s The

Mad King. It was not the last car in the story, however. Much royal

intrigue ensued as supporters of Leopold and Barney sparred for their

man’s

right to be king of Lutha. On September 3, 1914, Leopold arrived at the

cathedral in Ludstadt to marry Emma von der Tann. Captain Ernest

Maenck,

convinced that the man about to marry the princess was not Leopold, but

instead

Barney Custer, attempted to take action to prevent the ceremony.

“At the

first cross-street he turned up the side of the cathedral. The grounds

were

walled up on this side, and he sought in vain for entrance. At the rear

he

discovered a limousine standing in the alley where its chauffeur had

left it

after depositing his passengers at the front door of the cathedral. The

top of

the limousine was but a foot or two below the top of the wall. Maenck

climbed

to the hood of the machine, and from there to the top of the wall. A

moment

later he dropped to the earth inside the cathedral grounds.”

After using

the parked limousine to

gain entrance to the cathedral, Meanck, thinking it was Barney who was

about to

wed Emma, mistakenly assassinated Leopold, ironically clearing the way

for

Barney not only to marry Emma, but also to become the legitimate King

of Lutha.

ALAN'S MANY

ERBzine APPEARANCES

www.erbzine.com/hanson

BILL HILLMAN

Visit our thousands of other sites at:

BILL and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® John Carter® Priness of Mars® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All Original Work ©1996-2025 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective owners