Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Volume 8093

Did

Tarzan Ever Kill a Woman?

by Alan Hanson

In

Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan

stories,

the ape-man certainly was a prolific killer of his fellow men. He

didn’t kill

indiscriminately, though. Burroughs made it clear that when Tarzan

killed men,

they usually “had it comin’.” (That wasn’t always the case, though.

Except for

Kulonga, the natives that the young Tarzan killed just to get their

weapons in Tarzan of the Apes were

innocents.

Tarzan later regretted those slayings.)

The

topic here, though, is

whether or not

Tarzan ever killed a woman. There is a legal term for such an action.

It’s

“femicide,” defined

as the intentional

killing of a

woman with a “gender-related motivation.” In other words, “killing a

woman because she was a woman.” Tarzan was

innocent of that crime. However, he could be cited for causing the

death of women

for other reasons, such as in self-defense or in protection of his

family and

friends. Also, Tarzan fought in both world wars, when the killing of

enemy

women might become an unfortunate outcome in battle.

The

goal here, though, is to determine if Tarzan of the Apes/John

Clayton, Lord Greystoke ever willingly caused the death of a woman in

Edgar

Rice Burroughs’ tales of the ape-man.

Early Encounters With

Women

During

the period when Tarzan

was

transitioning from a creature of the wild to a civilized man, he

struggled to

reconcile his in-bred feelings about women with how he observed their

fear of

men in the civilized world. He voiced his confusion on the topic in a

conversation with Olga de Coude in The

Return of Tarzan.

“It

does not seem right that women should fear men. I am better acquainted

with the

jungle folk, and there it is more often the other way around. No, I

cannot

understand why civilized women should fear men, the beings that are

created to

protect them. I should hate to think that any woman feared me.”

Throughout

the early Tarzan

tales, the

hybrid ape-man/English lord indeed was a protector of women, first of

Jane from

the dastardly Russian, Nickolas Rokoff, in The

Beasts of Tarzan. Then, in The Son

of

Tarzan, he tried to shield Meriem from the impure advances of

the

evil

Swede, Sven Malbihn, and the less than honorable English gentleman,

Morison

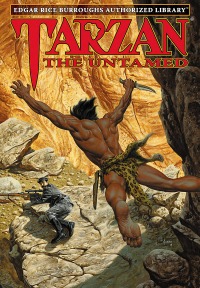

Baynes. In wasn’t until later, in Tarzan

the Untamed, that Burroughs’ tested Tarzan’s belief that men

are

the

protectors of women. Throughout the story, ERB gave Tarzan a strong

desire to

kill a certain woman.

Tarzan

Planned to Kill Bertha Kircher

ERB

set up the conundrum thus.

At the

outset of World War I, Tarzan became convinced that, while he was away,

a group

of German soldiers attacked his African home, killed his wife Jane, and

burned

her body beyond recognition. Tarzan immediately vowed to find and kill

the

German who had murdered Jane. Then … “After he had accounted for him he

would

take up the little matter of slaying all Germans who crossed his path,

and he

meant that many should cross it.”

Soon,

one who passed his path

was a woman —

the German spy Bertha Kircher. Tarzan knew she was a German spy

because, “He

had seen her at General Kraut’s headquarters in conference with the

German

staff and again he had seen her within the British lines masquerading

as a

British officer.” Later, when Tarzan saw her wearing the locket that

had been

taken from his dead wife’s neck, it further inflamed his hate for her

and his

resolve to kill her.

Tarzan

first had an opportunity

to affect

Bertha’s death by not interfering when he came across a lion attacking

her.

“What was she but a hated German and a spy besides?” was his initial

thought.

Then, after it occurred to him that the British military would like to

question

her, he stepped in to save her from the lion.

He

was still determined to kill

her

eventually.

“She

was very beautiful — that was undeniable; but Tarzan realized her

beauty only

in a subconscious way. It was superficial — it did not color her soul

which

must be black as sin. She was German — a German spy. He hated her and

desired

only to compass her destruction; but he would choose the manner so that

it

would work most grievously against the enemy cause.”

However,

when Tarzan noticed

Bertha was

wearing Jane’s locket, he angrily threatened to kill her on the spot.

“Tell me

who gave it to you or I will throw you back to Numa,” he raged. “I was

going to

take you to headquarters. They would dispose of you there; but Numa can

do it

quite as effectively. Which do you prefer?”

Tarzan

Realized He Couldn’t Kill a Woman

Bertha

later knocked Tarzan

unconscious and

fled. Later he confronted her again behind German lines after she

watched him

brutally kill a German officer. In the interim, he had come to the

realization

that he could not kill Bertha Kircher in the same way. “It would be

difficult

to take you back from here and so I was going to kill you, as I have

sworn to

kill all your kind,” he told her. “But you were right when you said

that I was

not such a beast as that slayer of women. I could not slay him as he

slew mine,

nor can I slay you who are a woman.”

To

be sure, Tarzan still wanted

Bertha

dead. While he couldn’t bring himself to kill her directly, he hoped

another

opportunity would arise to make it happen in a way that his conscience

could

sanction. That opportunity came when he discovered that a band of

native German

soldiers had abducted Bertha.

“Tarzan

of the Apes was haunted by the picture of a slight, young girl being

shoved and

struck by brutal Negresses, and in imagination could see her now camped

in this

savage country a prisoner among degraded blacks.

“Why

was it so difficult to remember that she was only a hated German and a

spy? Why

would the fact that she was a woman and white always intrude itself

upon his

consciousness? He hated her as he hated all her kind, and the fate that

was

sure to be hers was no more terrible than she in common with all her

people

deserved … Tarzan composed himself to think of other things, yet the

picture

would not die — it rose in all its details and annoyed him. He began to

wonder

what they were doing to her and where they were taking her. He was very

much

ashamed of himself as he had been after the episode in Wilhelmstal when

his

weakness had permitted him to spare this spy’s life. Was he to be thus

weak

again? No!”

After

rescuing Bertha from her

captors,

Tarzan had two more opportunities to affect her death through his

inaction.

First, when he saw a panther about to attack Bertha, ERB explained,

“Here again

might she die at the hands of others; but why consider it! He knew that

he

could not permit it, and though the acknowledgment shamed him, it had

to be

admitted.”

Soon,

though, there came to him

a way of

bringing about her death indirectly that would leave his hands clean.

He

deserted Bertha in the jungle hundreds of miles from civilization.

“She

knew that Tarzan had passed a death sentence upon her, and that the

moment that

he left her, her doom was sealed for it could be but a question of time

— a

very short time — before the grim jungle would claim her, for how could

a lone

woman hope successfully to combat the savage forces of destruction

which

constituted so large a part of existence in the jungle.”

Later,

though, when Tarzan’s

conscience

wore him down, he came to the same conclusion. He knew he could not

cause

Bertha Kircher’s death, not by any manner.

“ …

he never had found it in his heart to slay her as he had sworn to slay

all

Huns. He had attributed this weakness to the fact that she was a woman,

although he had been rather troubled by the apparent inconsistency of

his

hatred for her and his repeated protection of her when danger

threatened.”

By

the end of Tarzan

the Untamed, the ape-man fully accepted that he could not

harm a woman, even through inaction. When he could have left Bertha a

captive

among the mentally impaired men of the city of Xuja, Tarzan openly

declared,

“She may be a German and a spy, but she is a woman — a white woman — I

can’t

leave her here.”

“I Do Not

Harm Women”

Henceforth

in ERB’s Tarzan

stories, both as

a gentleman farmer and adventurer in Africa, Tarzan was portrayed as a

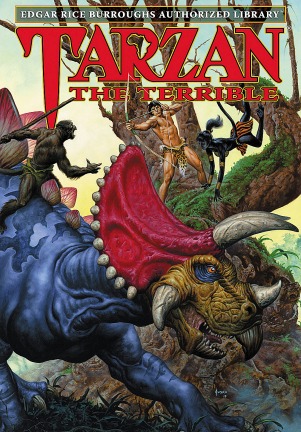

protector of women. In Tarzan the

Terrible, he went to distant Pal-ul-don to rescue and preserve

the

virtue

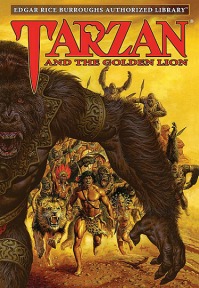

of his wife Jane. In Tarzan and the

Golden Lion, when Flora Hawkes told him how she conspired with

others to

steal gold from Opar, Tarzan responded, “You should know, Flora, that I

do not

harm women … You are a woman. I could not leave you alone in the jungle

to die,

no matter what you may have done.”

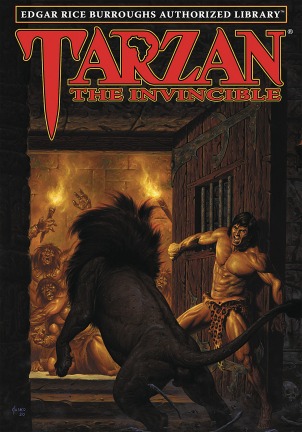

When

Tarzan returned to Opar in

Tarzan the Invincible, La

encouraged

him

to kill the priestess Oah, who participated in a revolt that deposed La

as

queen. “If we can kill Oah in the throne room,” La explained to Tarzan,

“they

would have no leaders.” Tarzan responded, “I cannot kill a woman.

Tarzan of the

Apes kills only in self-defense and for food, or when there is no other

way to

thwart an enemy.”

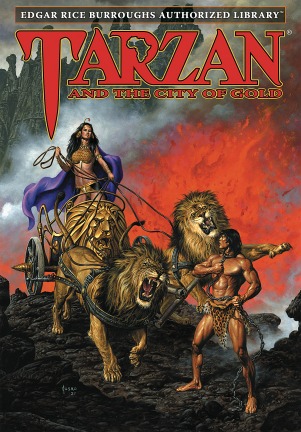

“So

you came to kill me,” Queen

Nemone of

Cathne said to Tarzan when he stood before her accused of being an

assassin in Tarzan and the City of Gold.

“Killing a

woman is no feat of arms,” he responded. “I do not kill women. I did

not come

to kill you.”

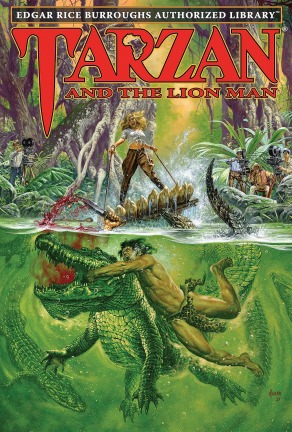

In

Tarzan

and the Lion Man, Tarzan actually threatened to kill a woman.

He

was

referring to the Balza, a human mutant outcast from the gorilla city of

London

(in Africa). “Go back,” Tarzan shouted at the pursuing gorillas, “or I

kill

your she.” It was just a threat that didn’t work, however. “They will

not

stop,” Balza told him. “They do not care if you kill me. You have taken

me. I

belong to you.” (Later she became a movie star in Hollywood.)

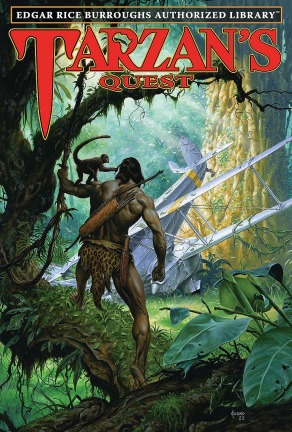

In

the last few Tarzan books,

the ape-man

again was portrayed as a protector of women. In Tarzan’s

Quest he traveled far from home to confront the Kavuru

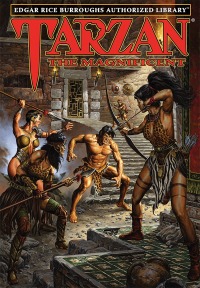

tribe that captured and killed native women. In Tarzan the

Magnificent, he declared, “I do not kill old men or

women or children unless they force me to.” In Tarzan and

“The Foreign Legion”,

Colonel Clayton refused Corrie Van

Der Meer’s request to go on a raid to free American prisoners held by

Japanese

soldiers. “You’d be an added responsibility for us,” he told her. “We’d

have to

be thinking of your safety when our minds should be on nothing but our

mission.”

The Young

Tarzan Almost Killed a Woman

That

brings us back to the

original

question. Did Tarzan of the Apes, despite all his denials that he

could, ever

kill a woman during ERB’s chronicles of the ape-man?

Well,

very early in his life he

was more

than ready to do so. In Tarzan of the

Apes, he was within seconds of stabbing to death a native woman

in

Mbonga’s

village. He was rummaging around in a native hut looking for something

to use

in a prank against the superstitious tribe, when a native woman

unexpectedly

entered the hut.

“Tarzan

drew back silently to the far wall, and his hand sought the long, keen

hunting

knife of his father. The woman came quickly to the center of the hut.

There she

paused for an instant feeling about with her hands for the thing she

sought.

Evidently it was not in its accustomed place, for she explored ever

nearer and

nearer the wall where Tarzan stood.

“So

close was she now that the ape-man felt the animal warmth of her naked

body. Up

went the hunting knife, and then the woman turned to one side and soon

a

guttural ‘ah’ proclaimed that her search had at last been successful.

Immediately she turned and left the hut …”

Raised

as he was in the wild,

it could have

been considered a natural act of survival for him to kill a native

woman. But

when he merged with the civilized world at age 21, he accepted its

general convention

that men are protectors of woman.

So,

we return again to the

initial

question: Did Tarzan ever kill a woman?

The answer is “yes.” Tarzan did kill a woman in the stories ERB

told of

the ape-man. In fact, he did it twice!

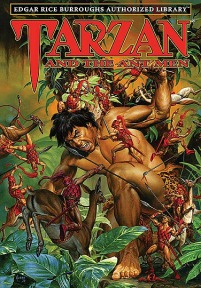

Tarzan

Kills His First Woman

The

first time was durinan

encounter with

an Alalus woman in Tarzan

and the Ant

Men. After his plane crashed inside the Great Thorn

Forest,

Tarzan

soon

encountered the Alalus people. According to ERB, “The hideous life of

the

Alalus was the natural result of the unnatural reversal of sex

dominance.” The

physically stronger females saw males as no more than reproductive

tools.

Unconscious

after the plane

crash, Tarzan

was “picked up” by a female Alalus and confined in a village corral.

Later, he

was threatened by an Alalus girl. The encounter tested Tarzan’s

assertion that

he could never kill a woman.

“And

now the girl was almost upon them. Tarzan was quite at a loss as to how

to

proceed against her. His natural chivalry restrained him from attacking

her and

made it seem most repellant to injure her even in self-preservation;

but he

knew that before he was done with her he might even possibly have to

kill her

and so, while looking for an alternative, he steeled himself for the

deed he

loathed; but yet he hoped to escape without that.”

Tarzan

side-stepped the situation when he and

an Alalus boy fled over the corral wall and escaped into the jungle.

Later,

though, Tarzan’s vow that he could not kill a woman was put to the

ultimate

challenge. Tarzan chose to intervene when an Alalus woman grabbed a

diminutive

“Minunian” man. The ape-man warned the woman to release her captive and

go

away. Instead, though, she raised her bludgeon and advanced toward

Tarzan, who

then fitted an arrow to his bow.

“‘Go

back’ he signed her. ‘Go back, or I will kill you. Go back, and put

down the

little man.’ She snarled ferociously and increased her pace. Tarzan

raised the

arrow to the level of his eye and drew it back until the bow bent … The

ape-man

hoped that the woman would obey his commands before he was compelled to

take

her life, but even a cursory glance at her face revealed anything but

an

intention to relinquish her purpose, which now seemed to be to

annihilate this

presumptuous meddler as well.

“On

she came. Already she was too close to make further delay safe and the

ape-man

released his shaft. Straight into her savage heart it drove and as she

stumbled

forward Tarzan leaped to meet her, seizing the warrior from her grasp

before

she might fall upon the tiny body and crush it.”

In

assessing this particular

situation, a

previous assertion by Tarzan should be recalled. The ape-man’s most

recent

statement on the issue was conditional. In Tarzan

and the Golden Lion,

the

ape-man told La, “I cannot kill a woman.

Tarzan of

the Apes kills only in self-defense and for food, or when there is no

other way

to thwart an enemy.”

Certainly, he warned the Alalus women with hand

signals,

voice commands, and actions that he would kill her if needed to protect

himself.

Tarzan

Kills Another Woman

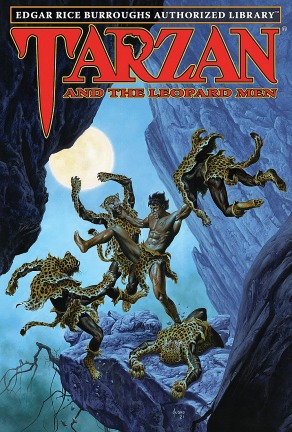

The

second incident involving

Tarzan

killing a woman occurred in Tarzan and

the Leopard Men. At one point, toward the end of the story, an

American

girl, Jessie Jerome (aka “Kali Bwana”)

was being held captive in a

pygmy tribe

village. When the tribe eventually decided to kill and eat Jessie,

Wlala, a

pygmy woman who was Jessie’s guard, volunteered to kill her.

Just

as Wlala grabbed Jessie by

the hair

and raised a knife to slay her, Tarzan arrived in the nick of time to

save

Jessie.

“To a

tree Tarzan made his way, keeping the bole of it between him and the

natives

assembled about the fires; and into its branches he swung just in time

to see

Wlala seize the girl by the hair and lift her blade to slash the fair

throat.

There was no time for thought, barely time for action. The muscles of

the

ape-man responded almost automatically to the stimulus of the

necessity. To fit

an arrow to his bow and to loose the shaft required but the fraction of

a split

second.”

As

described by ERB, the arrow

“passed

through the body of Wlala from behind, transfixing her heart.”

In

that situation, Tarzan

killed one woman

to save the life of another woman. In all honesty, though, the race of

the

woman Tarzan killed in that situation was the determining factor in the

ape-man’s

decision. Would Tarzan have reacted with lethal force, if a white woman

were

about to kill a pygmy woman? It’s a fool’s question, of course, as

Burroughs

would never have considered such a scenario.

THE END

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® John Carter® Priness of Mars®

are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2025 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the

respective

owner.