Pondering the Pleasure of the

Hunt

Examining Edgar Rice Burroughs’

Attitude Toward Sport Hunting

by Alan Hanson

“When I was a boy and young man,

I wanted to kill things as I think most boys and young men do … ”

“When I was a boy and young man,

I wanted to kill things as I think most boys and young men do … ”

Thus Edgar Rice Burroughs admitted

his early lethal attitude toward wildlife in a 1927 letter to a fifteen-year-old

Burroughs fan club president. There’s no evidence that while growing up

in Chicago young Edgar acted upon his latent desires. However, in his later

writing career of nearly four decades, Burroughs often explored the ethics

of man killing animals in the wild. An inspection of both his fiction and

non-fiction work reveals that ERB’s attitudes on the subject changed as

he grew older.

First of all, limits need to be

set. “All men are hunters — all women quarry,” Burroughs wrote in

The

Girl from Farris’s, but we’re not talking about that kind of hunting

here. Nor are we considering the killing of animals for food or in self-defense.

ERB always deemed such hunting justified and necessary for human survival,

both in Tarzan’s Africa and in the real world of the twentieth century.

Here we’re limiting our examination to Burroughs’ evolving opinions on

recreational hunting, the killing of animals for pleasure and trophies.

It’s doubtful Burroughs still considered

himself a “young man” when he began writing fiction at age 35. And

so his earliest stories lack the glorification of sport hunting that he

might have felt at a younger age. Instead, his first dozen or so novels

contain a rather balanced view of the sport. Taken together, the general

portrayal of recreational hunting in his early fiction is that the sport

was legitimate, even exciting at times, but that the feelings of those

who chose not to engage in it are to be respected as well.

Certainly, hunting wild animals

was portrayed as a noble pursuit on Burroughs’ first created world of Barsoom.

The opening trilogy of the author’s Martian series contains references

to “the great fur-bearing animals which the Martians so delight in killing,”

“the sport of hunting the strange and savage creatures which haunt the

jungle fastness,” and the enjoyment of traveling to the far north to

track and kill the “sacred apts” and orlucks. Later in the series,

Carthoris went north to hunt with the Jeddak of Okar, and Tan Hadron stalked

great white apes in Thark as the guest of Tars Tarkas. Clearly, Barsoom,

where the blood of a thousand creatures, human and animal alike, dripped

from John Carter’s sword, was not the locale Burroughs chose to explore

the ethics of hunting.

That backdrop generally would be

Tarzan’s Africa, where Burroughs was free to pose any number of moral questions.

His ape-man, obviously, was required to kill wild animals often for sustenance

and in self-defense. Occasionally the young Tarzan killed natives out of

hate or to obtain their weapons. He killed his great ape rivals Kerchak

and Tublat in a mixture of passion and political necessity, but none of

those deaths can be qualified as sport killings.

Toward the end of Tarzan of

the Apes, however, the ape-man killed a lion for what were clearly

sporting reasons. It started in an African west coast settlement, when

Tarzan explained his youthful attitude (he was 20 years old at the time)

about sport hunting to a group of European gentlemen and big game hunters.

“ … to me the only pleasure in

the hunt is the knowledge that the hunted thing has power to harm me as

much as I have to harm him. If I went out with a couple of rifles and a

gun bearer, and twenty or thirty beaters, to hunt a lion, I should not

feel that the lion had much chance, and so the pleasure of the hunt would

be lessened in proportion to the increased safety which I felt.”

Challenged by one of the gentlemen

to enter the jungle and kill a lion with only a knife and a rope, Tarzan

did so in one of the very few sport killings he committed during his thirty-year

life under Burroughs’ pen. “To Tarzan,” the author explained, “it

was as though one should eulogize a butcher for his heroism in killing

a cow, for Tarzan had killed so often for food and for self-preservation

that the act seemed anything but remarkable to him. But he was indeed a

hero in the eyes of these men — men accustomed to hunting big game.”

Incidentally, for killing the lion Tarzan collected ten thousand francs

on a wager.

Tarzan

Starts to Develop a Negative Attitude About Hunting

While writing The Return

of Tarzan in 1912, however, Burroughs began to give his ape-man

a decided anti-hunting philosophy, at least as it applied to one particular

animal. At the time, Tarzan was working for the French government posing

as a hunter in Algeria. Burroughs explained how the undercover ape-man

played the part of a hunter without really hunting.

“He would spend entire days in

the foothills, ostensibly searching for gazelle, but on the few occasions

that he came close enough to any of the beautiful little animals to harm

them he invariably allowed them to escape without so much as taking his

rifle from its boot. The ape-man could see no sport in slaughtering the

most harmless and defenseless of God’s creatures for the mere pleasure

of killing.”

However, in three stories written

in 1914 and 1915, Burroughs changed Tarzan’s environment, plucking him

from his West African jungle and transplanting him as a landed aristocrat

in British East Africa. As the only source of law and justice in the region,

Lord Greystoke laid down rules, many of which applied to big game hunting

in his country. In doing so, Tarzan was lenient with hunters, even encouraging

friends and acquaintances to come and hunt on his land.

Burroughs first revealed Tarzan’s

relaxed attitude toward big game hunting in The Eternal Lover,

when he (the fictional Burroughs), Barney Custer, and his sister Victoria

were among the guests on the Greystokes’ vast African estate. They were

there to hunt game, and there was plenty of it, as ERB explained.

“South of Uziri, the country

of the Waziri, lies a chain of rugged mountains at the foot of which stretches

a broad plain where antelope, zebra, giraffe, rhinos and elephant abound,

and here are lion and leopard and hyena preying, each after his own fashion,

upon the sleek, fat herds of antelope, zebra and giraffe. Here, too, are

buffalo — irritable, savage beasts, more formidable than the lion himself

Clayton says. It is indeed a hunter’s paradise, and scarce a day passed

that did not find a party absent from the low, rambling bungalow of the

Greystokes in search of game and adventure … ”

Victoria alone is said to have bagged

two leopards, numerous antelope and zebra, and a bull buffalo, which she

brought down “with a perfect shot within ten paces of where she stood.”

The Greystoke guests continued hunting all the way through the very morning

of their departure.

In The Son of Tarzan,

written in 1915, Lord Greystoke continued to allow big game hunting on

his estate. However, here we start to read of limits Tarzan placed on the

sport. Again, visitors were coming to the land of the Waziri. “A number

of English ladies and gentlemen had accepted My Dear’s invitation to spend

a month hunting and exploring with them.” The guests were allowed the

pleasure and rewards of the hunt but were not allowed to kill indiscriminately.

“ … with the coming of the London guests the hunting had deteriorated

into mere killing,” Burroughs noted. “Slaughter the host would not

permit; yet the purpose of the hunts were for heads and skins and not for

food.”

Later in the story, ERB explained

in greater detail Tarzan’s efforts to regulate sport hunting, not only

on his estate but also throughout the region.

“No white man came within a hundred

miles that word of his coming did not reach Bwana long before the stranger.

His every move was reported to the big Bwana — just what animals he killed

and how many of each species, how he killed them, too, for Bwana would

not permit the use of prussic acid or strychnine … Several European sportsmen

had been turned back to the coast by the big Englishman’s orders … and

one, whose name had long been heralded in civilized communities as that

of a great sportsman, was driven from Africa with orders never to return

when Bwana found that his big bag of fourteen lions had been made by the

diligent use of poisoned bait.”

Tarzan also did not allow the use

of tethered live animals to lure lions into the range of hunters’ guns.

“Bwana never countenanced such acts in his country,” Burroughs explained,

“as his word was law among those who hunted within a radius of many

miles of his estate.”

Lord

and Lady Greystoke Both Hunted for Pleasure

The bottom line, though, is that at

this time in his writing career, Burroughs was allowing trophy hunting

on Tarzan’s estate. And it wasn’t just their guests. In Tarzan and

the Jewels of Opar, Burroughs revealed that both Tarzan and Jane

participated in recreational hunting on their estate. When her husband

was absent, Lady Greystoke occasionally chose to “relieve the monotony

of her loneliness by a brief hunting excursion.” And we learn that

many times, “Tarzan of the Apes had, in a spirit of play and adventure,

elected to return for a few hours to the primitive manners and customs

of his boyhood, and … hunt the lion and the leopard, the buffalo and the

elephant after the manner he loved best.”

It’s also important to note, however,

that during this period we start to see a few Burroughs characters take

a personal stance against sport hunting. Meriem, later Tarzan’s daughter-in-law,

was one of them. Raised from childhood amidst the life and death struggle

of the jungle, she nevertheless developed a dislike of needless killing.

“She

never had cared particularly for the sport of killing,” Burroughs wrote

in The Son of Tarzan. “The tracking she enjoyed; but the

mere killing for the sake of killing she could not find pleasure in — little

savage that she had been, and still, to some measure, was.”

In 1919 Burroughs moved his family

from the mid-West to Southern California, settling on his Tarzana ranch

north of Los Angeles. This move led to a change in ERB’s personal attitude

toward recreational hunting, which would later be reflected in his fiction.

When he first moved onto the property, however, Burroughs fully intended

to do some hunting on the ranch, as the following passage from a March

1919 letter to friend Bert Weston indicates. At the time, the Burroughs

family was in the process of moving into the Tarzana ranch house.

“The range into which Tarzana

runs is very wild. It stretches south of us to the Pacific. We have already

seen coyote & deer on the place & the foreman trapped a bob-cat

a few weeks ago. Things come down and carry the kids out of the corrals

in broad day-light. Deeper in there are mountain lion … I have bought a

couple of .22 cal. rifles for Hulbert and myself beside my .25 Remington

and automatics, so we are going to do some hunting. Jack has an air rifle

with which he expects to hunt Kangaroo-rats and lions and I am going to

get them each a pony.”

In an interview four years later,

Burroughs discussed his hunting habits in more detail. In his article in

the June 3, 1923, issue of Oakland Tribune Magazine, Seth T. Bailey wrote,

“Burroughs is not a sportsman in one sense of the word. He does not

like to kill wild animals, except the predatory species. He will hunt all

day for a hawk or a rattlesnake, and pass up chances to shoot tree squirrels,

grouse or quail. He has never hunted big game, except the cougar or coyote.”

A few passages in the Tarzan stories

that Burroughs wrote around this time indicate that trophy hunting was

still allowed on the Greystokes’ African estate. However, actual descriptions

of such hunting are few compared to those in earlier Tarzan novels. One

thing Burroughs verifies during this period is that while Tarzan did kill

some animals with guns, he never did so for pure sport. “Tarzan was

an excellent shot,” we learn in 1918’s Tarzan the Untamed.

“With his civilized friends he had hunted big game with the weapons

of civilization and though he never had killed except for food or in self-defense

he had amused himself firing at inanimate targets thrown into the air …”

Burroughs’

Big Game Hunting Fantasy

While Burroughs stated in the 1923

interview that he had never hunted big game, apparently he fantasized about

doing so. The greatest big game hunter in Burroughs’ fiction during the

early 1920s was Burroughs himself. In the introduction to the magazine

version of The Moon Maid, written in 1922, ERB sent himself,

in his role as the story’s narrator, on a polar bear hunt in the Canadian

Arctic. It’s obvious Burroughs enjoyed the vicarious hunt, since he described

it at greater length and in much more detail than needed to frame the coming

story of Julian 5th.

After leaving his desolate camp

on the Arctic shore, Burroughs, rifle in hand, ventured out on the ice

in search of polar bear. Spotting one, he pursued it farther from shore,

only to discover the ice behind him had split, cutting off his return to

the mainland. Then the hunter became the hunted. The polar bear turned

and headed toward the sportsman. In stirring prose, ERB described how the

bear, despite having bullet after bullet pumped into him, advanced inexorably

toward the narrator, until it died within a foot of the hunter. It was

every big game hunter’s fantasy adventure.

In real life, meanwhile, by the

mid-1920s Burroughs had developed both a financial and emotional interest

in the development of the Tarzana community. In 1924 he had begun to sub-divide

his ranch property. In the years prior to that, however, Burroughs had

developed affection for the wildlife that roamed the low hills of his estate.

This led to a personal aversion for hunting and a bitter dislike for hunters

in the area.

In a 1926 letter to an English pen

pal, ERB wrote of his fondness for one particular wild animal and his determination

to protect it from hunters on his property. “I cannot derive any pleasure

from the taking of a wild animal’s life,” he confided. “I would

rather shoot a man than a deer, and I used to spend a great deal of time

during the deer season riding over my property to protect the deer from

a lot of counter jumpers who would just as soon shoot a doe as a buck.”

Burroughs used very similar language

five years earlier in his novel, The Girl From Hollywood,

the backdrop for which was clearly his Tarzana ranch. In the story he referred

to deer season as a time when “every courageous ribbon-counter clerk

in Los Angeles hied valiantly to the mountains with a high-powered rifle

to track the ferocious deer to its lair.”

Of course, Bara the deer was the

most common prey of Tarzan throughout his fictional life, but the ape-man

killed deer only for sustenance, and Burroughs never questioned this natural

use of animals. His contempt was for those who took pleasure in taking

the life of nature’s gentlest creatures. On several occasions Burroughs

used this, to him, repugnant act as a metaphor in his fiction. In fact,

Tarzan, the greatest deer hunter of all, was himself compared to a wounded

deer in Tarzan of the Apes. When the ape-man realized that

the Porter group had sailed away while he was nursing the injured D’Arnot

back to health, the Frenchman noticed the expression on Tarzan’s face.

It was “such a look as the hunter sees in the eyes of the wounded deer

he has wantonly brought down.”

The deer was not the only animal

Burroughs had sought to protect in the Tarzana hills. In the 1927 letter

to the fan club president, ERB explained his benevolent philosophy toward

wildlife extended toward many other creatures, including one he had once

hunted himself. “The coyotes come down every night close to the house,”

he explained, “and on many mornings during the summer I could shoot

them from my bedroom window, but I would much rather see them than kill

them.” He also wrote of the hundreds of tame quail that lived on his

property year round, and of how he had been able to “attract a great

deal of beautiful bird life” by putting lily ponds on his property.

“The birds seem to quickly learn that they will not be molested,”

he observed.

Burroughs

Turns Hostile to All Forms of Hunting

By 1927 Burroughs had become openly

contemptuous of all forms of recreational hunting. In the September issue

that year of the Tarzana Bulletin, Burroughs blasted Utah State Fish and

Game commissioner David Madsen for inviting hunters and fishermen, as Burroughs

characterized it, to “come and slaughter the game in his state.”

Burroughs continued, “Here’s hoping they mistake David for a deer.”

In the same article, ERB vilified bird hunters everywhere.

“It is the open season for doves

and the early morning landscape is dotted with heroic sportsmen stalking

these fierce denizens of the stubble fields. Compared with English sportsmen

they are pikers who bring the blush of shame to every right-minded, red-blooded

American of the he-man, wide open spaces, for while the American is trudging

around in the dust all morning bagging a dozen handfuls of blood-soaked,

bedraggled feathers, the toff with the monocle, up from London for the

Scottish grouse season, reclines at ease in a comfortable shelter while

beaters herd the birds along until they can be flushed to fly directly

above his gun. Some forty years ago John Augustus de Grey, seventh Baron

Walsingham, at the age of 78, made a record which, thank God, still stands

unbroken: 1070 birds killed in one day with one gun! Had I chanced to be

born with the name de Grey I should petition the Legislature to relieve

me of the odium.”

(Burroughs may not have been related

to an unsportsmanlike, bird-killing English peer, but Tarzan was. In Jungle

Tales of Tarzan, ERB explained that while the ape-boy hunted for

food in Africa, the usurper of his title, Lord Greystoke, “was hunting,

or, to be more accurate, he was shooting pheasants” in England. With

two guns, a “smart loader,” and twenty-three beaters driving the

quarry to his location, Lord Greystoke’s blood tingled as he shot down

“many more birds than he could eat in a year.”)

In the same issue of the Tarzana

Bulletin, Burroughs addressed his fellow landowners, extolling them to

protect the local wildlife, both to enhance the value of their property

and as a legacy for their children. “The pleasure of destroying it (if

there can be any pleasure in destroying a beautiful and harmless creature),

is ephemeral at best,” he preached, “and if it is destroyed it can

never be replaced.”

ERB made no attempt to restrain

his contempt for sport hunters in Tarzana. He called them “Piltdowners”

and suggested the tables be turned on these destroyers of wildlife. “If

we are going to rid Tarzana of any wildlife let us start in on the Piltdowners.

The writer of this has been shagging them off of Tarzana for many years.

This morning he ran six off. There should be an open season for Piltdowners

extended from January 1 to December 31.”

Burroughs even spoke out in support

of snakes, long the most detestable of creatures in Tarzan’s Africa. They

are “among the most useful creatures we have,” Burroughs explained

to his neighbors, since they preyed on harmful animals. “Anyone who

kills a bull snake, a gopher snake or a king snake should be brained —

if he has any brains.”

Just a few months before his comments

appeared in the Tarzana Bulletin, Burroughs had finished writing his eleventh

Tarzan novel, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle. In it the character

of American stockbroker and big game hunter Wilber Stimbol fits the profile

of what Burroughs called a “Piltdowner.” Stimbol came to Africa

determined to get a half dozen trophies to add to his collection. After

failing to bring down a gorilla with an initial shot, the American yelled

to his askari, “Come on, get after him! I’ve got to have him. Gad! What

a trophy he’ll make.” Ordered to leave Africa by Tarzan, Stimbol would

have none of it. “You forget that I’m here to hunt, and what’s more

I’m going to hunt,” he declared. “I’m not going back to the coast

by a damned sight, monkey-man or no monkey-man.” Of course, in Burroughs’

ideal fictional world, the arrogant hunter was forcibly deported from Tarzan’s

Africa. ERB, no doubt, wished he could have had the same legal power to

deal with all hunters in Tarzana.

In My Diversions, an article

written in 1929, Burroughs revealed a deepening reverence for all wildlife

in the Tarzana hills. “My happiest hours are spent in the upper pasture,”

he declared. There he saw jackrabbits, blue jays, and a road runner, with

whom Burroughs regularly shared a “minute of silent communion.”

The bird was “much better company than the majority of the so-called

human race,” the author observed. In the spring deer jumped the fence

into the pasture and walked fearlessly among the horses being ridden by

Burroughs and his sons. “I think the animals in the upper pasture know

that my boys and I will not hurt them,” he explained.

ERB continued to see hunters as

a constant threat to his idyllic relationship with area wildlife. “I

was on very good terms with a little coyote too, until one of my men shot

at him,” Burroughs lamented. “I have not seen him since, and I am

sorry to have lost his company.” Then there were the quail, hundreds

of them, that Burroughs noted were “waiting innocently and trustingly

for some damn fool with a shotgun to come along.”

Burroughs

Debates Hunters’ Effect on Balance of Nature

A few months after writing My Diversions,

Burroughs began work on a Western novel, The Deputy Sheriff of Comanche

County. In the story, he used a mountain lion hunt as an opportunity

to consider the effects of sport hunting on the balance of nature. After

four hunting dogs treed a lion, the guides and guests from an Arizona dude

ranch discussed who should have the “honor of shooting the quarry.”

The ranch foreman suggested the two female guests shoot the cat at the

same time. “I don’t care anything about shooting him,” responded

Kay White. “I’d much rather see him alive. Doesn’t he look free and

wild and splendid?” One of the hunters explained that the lion was

a deer killer, and that, “If it warn’t for them sons-o’-guns, we’d have

plenty of deer in these hills.” Kay countered with a warning that killing

predators, like the lion, can have the opposite effect on the balance of

nature. “Like they have in the Kaibab forest,” she said, “since

they killed off all the lions — so many deer that there isn’t food enough

for them and they’re starving to death.”

Kay’s plea to spare the animal was

ignored, and Dora Crowell, the other woman in the hunting party, killed

the lion. After the party returned to the ranch house, a camera recorded

Dora with her trophy. “It was propped up and photographed with Dora

standing beside it with her rifle. It was stretched out and measured and

then is was photographed again while Dora stood with one foot on it.”

In Deputy Sheriff,

Burroughs declined to pass judgment on Dora’s prized trophy. Perhaps that

was because the virulent anti-hunting Burroughs had two similar trophies

prominently displayed in his Tarzana office at the time he was writing

the novel. Writer Lee Shippey, there to interview ERB for a 1929 article

in the Los Angeles Times, saw a huge bearskin rug and a great tigerskin

draped over a table in the office, and asked Burroughs about them. “I

brought them down,” Burroughs explained, “not with one volley, but

with one volume. They’re gifts from Tarzan admirers. I’m really too fond

of animal life to be much of a hunter. I carry a gun while riding about

the ranch, but only because I’m my own ranger.”

That Burroughs carried a gun while

patrolling his Tarzana property demonstrates that his dislike of sport

hunting did not mean he was opposed to gun ownership. On the contrary,

ERB owned and advocated the responsible use of firearms throughout his

adult life. This attitude also found its way into his fiction occasionally.

For instance, in his 1931 novel Tarzan Triumphant, American

geologist Lafayette Smith came to realize that his college education had

not provided him with the practical skills necessary for survival in Africa.

“I used to feel sorry for the boys who wasted their time at shooting

galleries and in rabbit hunting,” he told a companion. “Men who

boasted of their marksmanship merited only my contempt, yet within the

last twenty-four hours I would have traded all my education along other

lines for the ability to shoot straight.”

However, while Burroughs supported

the rights of citizens to own guns, he continued into the 1930s to berate,

in both his personal statements and his fiction, those who found enjoyment

in killing animals. “I see no pleasure or sportsmanship in shooting

dove or quail,” he said in a 1930 radio interview. “The man who

shoots one of the beautiful deer that are yearly growing scarcer in our

hills, and can boast of it, should have both his heart and his head examined

— there is something wrong with them.”

Hunting

Human Heads — “A Splendid Idea,” Says Tarzan

Hunting played a part in several of

Burroughs’ Tarzan stories written in the 1930s. The subject is most prominent

in 1931’s Tarzan and the City of Gold, in which ERB again

explored the ethics of sport hunting. In the story, Tarzan found himself

involved in the intrigue between the queen and her nobles in the lost city

of Cathne. Since for them the hunting of humans with lions was both a political

tool and a recreational sport, the ape-man was inevitably drawn into the

activity.

It proved an ethical dilemma for

him. On one hand, men hunting men instead of animals appealed to his primitive

sense of fairness. “I rather like the idea,” he explained. “In

the world from which I come men fill their trophy rooms with the heads

of creatures who are not their enemies, who would be their friends if man

would let them. Your most valued trophies are the heads of your enemies

who have had equal opportunity to take your head. Yes, it is a splendid

idea.” However, when invited to participate in a hunt in which lions

were to run down and tear apart an unarmed slave, Tarzan intervened as

a matter of principle. “I didn’t approve of the ethics of the hunters,”

he explained. “The poor devil they were chasing had no chance. I went

ahead, therefore, through the trees until I overtook the black; then I

carried him for a mile to throw the lions off the scent.”

Of course, Burroughs continued to

write Tarzan stories until near the end of his life. In his final few tales

of the ape-man, ERB hardened Tarzan’s stance toward sport hunters in Africa.

For decades Burroughs had allowed Lord Greystoke to give permission to

visitors on his African estate to hunt big game, in moderation, and to

add trophies to their collection. In his final adventures, though, Tarzan

seemed to have the same loathing for all sport hunters in his domain that

Burroughs himself had for the same group on his Tarzana property. In his

final piece of fiction, an unfinished Tarzan novel started in 1946, Burroughs

wrote that the “needless slaughter of game” was a crime that Tarzan

“constantly sought to prevent.” Also in that incomplete manuscript,

ERB included the following unconditional statement of Tarzan’s disdain

for trophy hunters:

“Tarzan was definitely unsympathetic

toward people who came from other continents to kill the animals he loved

merely to have trophies to hang on their walls, or those who came in search

of mythical treasure and incidentally killed his animals for thrills.”

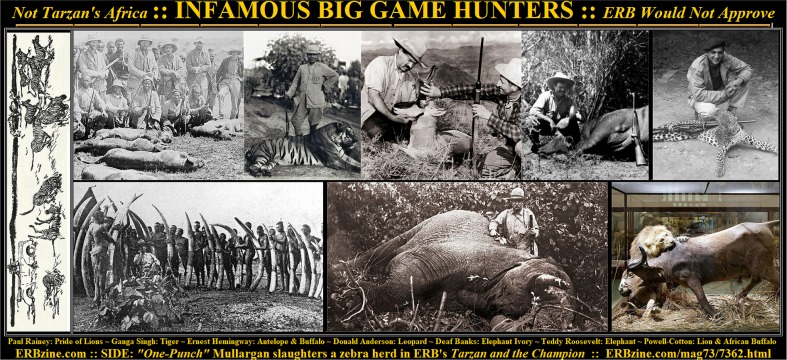

Such trophy-motivated thrill killing

of animals in Africa was the theme of Burroughs’ 1939 short story, Tarzan

and the Champion. After winning the heavyweight championship in

New York City, “One-Punch” Mullargan decided to take a vacation.

No, he wasn’t going to Disneyland. Instead, “We’re goin’ to Africa,”

he told his manager. “You see them heads in that guy’s house what we

were at after the fight the other night, didn’t you? Lions, buffaloes,

elephants. Gee! That must be some sport.” Once in Africa, Mullargan,

firing a machine gun from a fast-moving lorry, mowed down dozens of zebra

and elephants at a time. His goal matched his ego. “I’ll have one of them

photographer bums take my pitcher settin’ on top of a thousand heads,”

he declared. “That’ll get in every newspaper in the U.S.”

Tarzan, who viewed the slaughter

in “cold anger,” followed along and “mercifully put out of their

misery those of the animals which were hopelessly wounded.” When he

came upon Mullargan, Tarzan would have killed the American had a group

of unfriendly natives not stopped the execution. As the two men waited

in a hut to be tortured and eaten at a native feast that evening, Tarzan

lectured Mullargan.

“You are worse than the Babangos.

You had no reason for hunting the zebra and the elephant. You could not

possibly have eaten all that you killed. The Babangos kill only for food,

and they kill only as much as they can eat. They are better people than

you, who will find pleasure in killing.”

The American then had an epiphany

that Burroughs no doubt wished all sport hunters everywhere would have.

“I been thinkin’, Mister,” a remorseful Mullargan said to Tarzan,

“about what you was sayin’ about us hurtin’ the animals an killin’ for

pleasure. I aint never thought about it that way before. I wishst I hadn’t

done it.”

There is an anti-hunting statement

in nearly all of Burroughs’ later Tarzan stories. In Tarzan and “The

Foreign Legion,” Tarzan asserted “… years ago I learned to kill

only for food and defense. I learned it from what you call the beasts.

I think it is a good rule. Those who kill for any other reason, such as

for pleasure or revenge, debase themselves. They make savages of themselves.”

Later in the story, Tarzan shot

a deer as a meal for the group. “Of course it was all right to kill

for food,” thought one of the American pilots. Burroughs no doubt believed

the same thing. Despite the abhorrence he developed for sport hunters,

the author remained an unrepentant, life-long meat-eater. “I am going

right ahead eating prime beef,” Burroughs declared in a 1937 article

in the Los Angeles Times, adding a note of fairness, “and I accord to

the man-eaters their inalienable right to go on eating us, provided they

can catch us.”

In summary, during his life Edgar

Rice Burroughs developed an ever-deepening respect and affection for wildlife,

and that led to an ever-hardening loathing for recreational hunting. Both

attitudes were reflected in his spoken and written statements, and often

in his fiction, through the years. These feelings were probably formed

at sometime in his youth, but they were certainly solidified by his communion

with the quail, the roadrunner, the deer, the coyote, and many other species

during his almost daily horseback rides in the Tarzana hills in the 1920s.

Repeating the Burroughs statement

that opened this essay is an appropriate way of closing it. This time,

though, the conclusion of the statement will be added. It very neatly summarizes

why Edgar Rice Burroughs felt the way he did about recreational hunting.

“When I was a boy and young man,

I wanted to kill things as I think most boys and young men do, but as we

grow older we take more pleasure in life than death.”

— the end —

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()