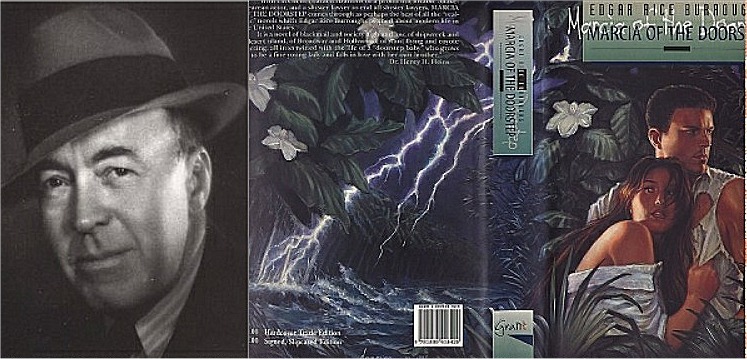

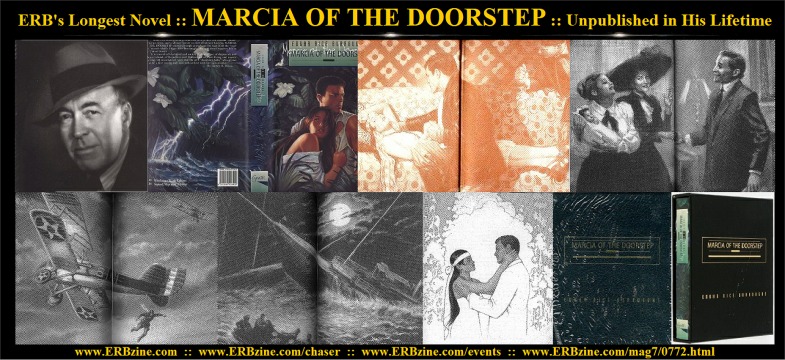

"Marcia of the Doorstep"

A Dream Come True

by Alan Hanson

As the calendar turned over to the year 2000, Burroughs

fandom still found itself celebrating the spectacle that was the Disney

Tarzan movie. If an impromptu vote had been taken, no doubt Burroughs

fans then would have selected that as the most important Burroughs event

since the ERB revival of the mid-sixties. As much as I appreciated the

Disney movie and all it provided Burroughs fans, for over a year I had

patiently awaited another event that, for me, would easily rate as the

most significant ERB "happening" of the previous three decades. It finally

came on December 18, 1999, when a copy of Marcia of the Doorstep

arrived at my front door.

Of course, fans are fans of ERB for many reasons, but

for a fan like me, whose focus had always been upon reading the stories

themselves, nothing, not even the colossal hoopla of a Disney movie, can

compare to the thrill of reading a Burroughs story for the first time.

And if the dozen or so other pieces of ERB's fiction that have remained

unpublished since the author's death in 1950 were all published at once,

to me that could not compare to the publication of Marcia of the

Doorstep. The opportunity to read this, the last remaining Burroughs

full-length novel heretofore left unpublished, fulfilled my most cherished

dream as a Burroughs fan. Not since the publication of I Am a Barbarian

in 1967 have ERB fans had the pleasure of reading a "new" Burroughs novel.

I came to ERB fandom with many others in the Burroughs

revival of the mid-sixties. By 1967, with the release of Barbarian,

I had read all the significant Burroughs fiction that had been published.

During the decades that passed since then, a few precious unpublished pieces

of Burroughs fiction surfaced, but, for the most part, fans like me have

had to be content with rereading the published list of Burroughs titles.

I couldn't complain about that, as doing so had given me much pleasure

through the years. However, I always hoped that someday I would be able

to read the stories that remained unpublished, and foremost among them

was Marcia of the Doorstep.

Reverend Heins First Review "Marcia"

As a young Burroughs fanzine reader, I was familiar with

the title, but knew little about Marcia of the Doorstep until

Henry Hardy Heins’ article on the novel appeared in “ERB-dom #67”

in 1973. (Heins’ article was actually written in 1966 at the request of

Hulbert Burroughs, who asked Rev. Heins to read the manuscript and comment

on its potential for publication.) As in demand as Edgar Rice Burroughs

was in the 1920s, one would have assumed that there was something very

amiss with a novel written then for which he could never find a publisher.

And yet, Heins in his article contended that, "Marcia of the Doorstep

comes through as perhaps the best of all the ‘realistic’ novels which Edgar

Rice Burroughs penned about modern life in the United States." At that

time, there were only three other published Burroughs titles that fell

into the category of realistic novels. They were The Girl From Hollywood,

The

Efficiency Expert, and The Girl From Ferris's, all

of which I enjoyed reading very much. In particular, The Girl From

Hollywood was then, and remains, one of my favorite Burroughs novels.

And so when Rev. Heins, who judgment in such matters I thoroughly respected,

concluded that it was “far better than the other ‘GIRL’ stories”

by ERB, it planted in my Burroughs heart of hearts a fervent hope that

someday I would get an opportunity to read that “lost” novel.

As the years, and then the decades, began to melt away,

my hopes for the publication of Marcia of the Doorstep began

to fade, and with good reason, I thought. Even Heins, as much as he liked

the novel, had to conclude that there was no market in modern times for

the “soap opera” that was Marcia. Heins asked Hulbert

Burroughs to consider printing a “limited edition,” so Burroughs fans could

read it, but after the financial bath ERB, Inc., took on its 1967 publication

of I Am a Barbarian, surely Hulbert was in no mood to publish

an even longer novel like Marcia. Back, then, into the same

drawer, file, or box where it had collected dust the previous 42 years

went the manuscript of Marcia of the Doorstep, to be forgotten

again for another three decades.

When I first heard the news in the mid-1990s that Donald

Grant was going to publish Marcia, I was quietly optimistic,

but it wasn't until Grant actually accepted prepayment for the book in

1998 that my hopes began to rise. Prepayments, however, could always be

refunded, so I refused to get excited until the book was actually in my

hands. So, as the Disney Tarzan movie consumed fandom during 1999,

I quietly awaited the fulfillment of a long cherished dream. It came true

on December 8, 1999, and to tell the truth, I could hardly believe it.

A Story of Love of Adventure

Reverend Heins wrote that back in 1966 he read Marcia

in two evenings and was reluctant to put it down for interruptions. I took

double that time — four evenings. I read slowly, savoring every line, since

I knew for certain it would be the last time I would read a Burroughs novel

for the first time. A standard book review usually includes a summary of

the story's events, but this will not be a typical review. Rather, what

follows are simply some observations about Marcia of the Doorstep

that came to my mind when I read it the first time.

Remembering Heins’ contention that Marcia

was better than A Girl From Hollywood, I found myself comparing

the two novels as I read Marcia. Respectfully, I had to disagree

with Rev. Heins, for, in the end, I concluded that The Girl From

Hollywood was a much better novel. For starters, the characterization

in Marcia is weak compared to the earlier novel. The sympathy

the reader feels for Marcia Sackett, with all her love complications, is

not nearly as intense as that generated for Shannon Burke, as she struggled

with drug addiction. Colonel Pennington, the family patriarch in The

Girl From Hollywood, is much stronger and more lovable than his

counterpart in Marcia, Marcus Aurelius Sackett. Even the

villain in Marcia, the dastardly Jewish lawyer Max Heimer,

doesn't provoke the intense dislike and loathing the reader feels for The

Girl From Hollywood creep, Wilson Crumb. Marcia of the Doorstep

has

a multitude of characters, many of them interesting, but none really memorable.

Where Marcia really suffers in comparison

to The Girl From Hollywood, however, is in its lack of a

social message. In the Hollywood story, Burroughs made an honest effort

to pen a highly realistic novel. The themes dealing with the evilness of

drugs and city life versus the redeeming influences of country life are

repeatedly and effectively reinforced throughout the novel. In Marcia,

however, it is difficult to identify a single unifying theme, unless it

is something like the enduring nature of romantic love, hardly a theme

of societal importance, then or now.

Perhaps one of the reasons Marcia received

so many rejections is that Burroughs couldn't seem to make up his mind

just what kind of novel he wanted it to be. It lacks the strong social

theme of a “realistic” novel. An indication that Burroughs thought it might

qualify as a romantic novel was his submission of it to Love Story Magazine.

In the end, though, Marcia of the Doorstep comes across as

more of an adventure story than anything else, although there is not a

whole lot of action in it.

In fact, instead of The Girl From Hollywood,

the ERB novel that Marcia resembles most is The Mucker.

The wide scope of settings in both novels is nearly the same. In The

Mucker, significant action takes place in several states, including

Illinois, California, Kansas, Texas, and New York. Action in Marcia

of the Doorstep is spread among the states of New York, California,

Illinois, and Arizona. Both novels have sequences in Mexico and in the

American territory of Hawaii. Both include shipwrecks and struggles for

survival on lost Pacific Islands. Each novel centers on the lead

characters overcoming a seemingly insurmountable barrier to achieving the

love of a man. In The Mucker, social class separates Billy

Byrne and Barbara Harding, while in Marcia of the Doorstep,

Marcia Sackett and Jack Chase are kept apart by the specter of incest.

There are differences in the two novels, of course, but in general, those

who like The Mucker, will probably like Marcia of the

Doorstep. Both belong on the same list of Edgar Rice Burroughs’

non-series adventure novels.

Repetitive Themes — Hollywood,

Suicide, Jews

Three other topics jump out to the reader of Marcia

of the Doorstep — Hollywood, suicide, and Jews. Burroughs treatment

of Hollywood in Marcia is much more positive than it is in

The

Girl From Hollywood, which was written in 1922, two years before

Marcia.

In the earlier novel, Hollywood and its burgeoning movie industry are portrayed

as impersonal and corruptible. In Marcia of the Doorstep,

Hollywood is depicted as essentially a harmless place that has drawn to

its bosom displaced by respectable stage performers looking to make the

transition to the big screen. ERB's change in attitude toward Hollywood

may have been a result of developing a closer relationship with the Southern

California film crowd. ERB biographer Irwin Porges reported that during

1924, when Marcia was written, there was an active social

life at ERB's Tarzana ranch. Weekends were essentially open house time,

and ERB's guests often included members of the Hollywood film colony. There

had been no Tarzan movies made since 1921, and so perhaps a fading resentment

with how Hollywood had treated Tarzan, combined with getting to know the

film crowd socially, resulted in ERB developing a more positive attitude

toward Hollywood, which then found expression in the writing of

Marcia

of the Doorstep.

Suicide was an element ERB used in many of his stories,

but in Marcia of the Doorstep there is an orgy of self-destruction.

No less than four characters, all men, attempt suicide. Two succeed. The

story opens with John Hancock Chase, Jr., shooting himself rather than

have it be known that he fathered a baby during a drunken one-night stand.

Later, facing financial ruin, Marcia’s adopted father unsuccessfully tries

to gas himself to death. Jack Chase, depressed by the belief that

the woman he loved was his sister, came within a second or two of putting

a bullet in his own head. Finally, stunt pilot Dick Steele leaped

from his own airplane after becoming convinced he could never possess Marcia.

There is nothing wrong with an author using suicide as an element in a

story, but in Marcia of the Doorstep it is overdone. Having

four different characters turn suicidal in response to kinds of emotion

stress that most people are able to work through weakens the story. By

allowing his characters to take the easy way out of their problems, ERB

comes across as taking the easy way out of his plot complexities.

Finally, there is the Jewish issue in Marcia of

the Doorstep. When it first became known that Donald Grant would

publish the novel, it was rumored that there were unkind references to

Jews in the text and that they might be removed before publication. In

his introduction to the book, however, Danton Burroughs explained, in the

interest of authenticity, these racial references had not been taken out.

Certainly, the Max Heimer character, an unscrupulous Jewish lawyer who

commits fraud and embezzlement for financial gain, could be viewed by some

as an unfair Jewish stereotype. In the dialogue, Heimer is referred to

as a “nice little ‘Jewboy’” and a “dirty little kite.” In addition, the

narration contains the following generalization. “Jews of Heimer’s type

are always prone to surround themselves with well favored employees of

the opposite sex, and each of the other four attorneys who shared the common

outer office with Heimer were of his kind.” So, for those who care

to find them, there are slurs and derogatory statements about Jews in Marcia

of the Doorstep. However, considering Heimer is a main character,

there are relatively few such expressions in the story, and reasonable

readers will take no offense where none was intended.

In fact, Burroughs took some action to diminish the negative

characterization of Jews in the story. For his article, Rev. Heins read

a typewritten manuscript of Marcia. Of that manuscript, he

reported the following.

“The original typing at all points always emphasized,

in sometimes uncomplimentary terms, that the lawyer was a Jew, but repeated

references to “the Jew” — once even ‘kike’ in a line of dialogue — have

all been crossed out by ERB and replaced by softer phrases — “the man,”

“the fellow,” “chap,” etc.”

Heins’ statement is a little confusing, though, since

the word “kite” does appear in the Donald Grant edition, Perhaps some or

all of he crossed-out terms were put back in the text before publication.

Heimer’s Jewish stereotype is softened a bit toward the very end of the

story, when it is revealed that Judge Isaac Berlanger, the high-principled

lawyer of the Chase family, is also Jewish. Berlanger tells Heimer, “Yes,

I'm a Jew, and I'm proud of it; but I'd put you behind the bars, where

you belong, quicker than a Gentile, for what he might do would bring no

disgrace upon my race as you and such as you have.” It is interesting,

though, that although Judge Berlanger appears several times throughout

the story, it was not until the very end that he was revealed to be a Jew.

Perhaps ERB made Berlanger a Jew at the last minute to show the reader

that not all Jewish lawyers were dishonest.

A Turning Point for ERB

The time has come to assess the significance of Marcia

of the Doorstep within the body of ERB's work. For starters, to

fairly judge the novel, it is necessary to understand the time frame in

which it was written. ERB's notebook reveals that he wrote the story between

April and October of 1924. Six months to write a novel, even a long one

like Marcia, was a long period for Burroughs. Even more intriguing,

though, is that it was the only story he wrote in 1924. Why was it that

an author, at the height of his popularity, would write only one novel,

and such an atypical one, in a calendar year?

Fortunately, the Porges biography helps answer that question.

In 1924, instead of writing, Burroughs’ energy was being devoted mostly

toward several money-making projects. Occasionally, he was renting his

Tarzana ranch to film companies for location shooting. In early 1924, though,

he became involved in the most ambitious of his business enterprises with

the sale of 120 acres of his Tarzana Ranch for the creation of the

El

Caballero Country Club. His partners convinced Burroughs to take on

the management of the project, and to that end, Burroughs took a downtown

office to handle the membership drive, building plans, and the club program.

Porges reports that when ERB came home in the evenings

during this period, he was overcome by fatigue, and so it is surprising

that he had the time or energy to write anything during this period, much

less a 125,000 word novel. In a letter to his brother Harry, ERB explained,

“I

am giving up my writing and practically everything else to put this club

together.” To add additional stress, the country club project was an

ongoing financial nightmare for Burroughs, and so it is understandable

that the novel he wrote while in this harried frame of mind would not be

his best work.

A couple of years later, in a 1927 letter to his McClurg

editor Joseph Bray, ERB explained that Marcia was written

at a time when his mind “was occupied by other things,” and that

the “rottenness” of the novel was a result of his “mental attitude”

at the time. Being aware, then, of how ERB was distracted by business concerns

during the writing of Marcia of the Doorstep helps the reader

understand, in part, why this novel lacks the focus and passion so often

present in his other fiction.

Business distractions aside, there is also the question

of why ERB was writing that kind of novel at that time. The novel Burroughs

wrote immediately preceding Marcia was Tarzan and the

Ant Men, and while many critics and fans alike have considered

it one of the better Tarzan stories, it is clear that by 1923 Burroughs

was fed up with Tarzan and disliked writing Ant Men. During

the writing of the novel, he confessed the following in a letter to Munsey

editor Robert Davis. “Instead of enjoying my work, I am coming pretty

near to loathing it … If I had not promised you this one I would chuck

it right where it is.”

Clearly, then, after finishing Ant Men,

Edgar Rice Burroughs felt a desire to change the direction of his writing.

The writing of Marcia of the Doorstep was a rebellion against

the formula-written Tarzan novels that he was feeling pressured to produce.

In attempting to write a realistic novel, Burroughs was again trying to

realize his dream of being accepted as a serious writer of mainstream fiction.

He had tried it and failed in 1919 with The Girl From Hollywood,

and, unfortunately, he would fail again with Marcia of the Doorstep.

Despite multiple submissions, he was unable to sell the story to any magazine.

And, unlike The Girl From Hollywood, which ERB insisted in

publishing in book form despite lack of interest, he made no effort to

find a book publisher for Marcia of the Doorstep. In fact,

according to Porges, Burroughs did not even send the manuscript to Joseph

Bray at McClurg because he knew the editor wouldn't like it.

In the career of Edgar Rice Burroughs, then, Marcia

of the Doorstep, although it was never published during his lifetime,

was a turning point. It was his last attempt to break free of the Tarzan-Fantasy

mold that he felt had entrapped him. Beginning in 1925, with the writing

of The Master Mind of Mars, ERB no longer demurred when editors

asked for Tarzan and Mars stories. Perhaps, whenever the old dream of critical

acceptance arose in his heart, he had only to remember the six wasted months

spent writing Marcia of the Doorstep in 1924. That probably

was enough to remind him of his destiny as a writer — and then he reluctantly

conjured up Tarzan again.

~ THE END ~

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()