Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive

Volume 1931

GANYMEDE OR BUST

By Den Valdron

Part 2: The Forgotten Sea of Mars

THE FORGOTTEN SEA OF MARS AND THE BURROUGHS REVIVAL

It was in this overheated, hothouse environment that young Michael Resnick grew up. Born in 1942, he would have just been coming of age as a sci-fi geek in 1956, when Palmer was starting his Tarzan on Mars campaign.I can imagine a young, undiscriminating fourteen year old devouring issues of Amazing Stories and Other Worlds, omnivorously reading Campbell’s Astounding, hunting Burroughs Tarzan and Barsoom paperbacks. I could see him getting quite caught up in Palmer’s campaign. Perhaps there’s an angry but sincere letter signed Michael Resnick in the Burroughs archives demanding that John Bloodstone be designated as Edgar Rice’s literary successor. Who knows? The world is a bit different when you’re fourteen years old and its all shiny and brand new.

But despite the efforts of a Palmer, or a young Resnick, Tarzan on Mars was not going to be published. So, Mike Resnick, just as probably dozens of other precocious young fans at the time and after, decided to write his own Tarzan on Mars adventure.

As I gather, Resnick has John Carter summoning Tarzan to Mars. Why would Carter need Tarzan? Because Tarzan has a unique skill.... He can swim. And apparently, there’s a ‘Forgotten Sea’ on Mars. Ouch. I mean... Just... Ouch. I’m sure that this was a masterstroke for a precocious fourteen-year-old but looking back the idea simply seems embarrassingly goofy. The young Resnick got about 40 pages into it, and then apparently dropped the idea, unfinished.

A few years later, around 1964 or 1965, a fanzine was looking to publish a story with Burroughs characters. Somehow this rolled around to Resnick, and he dug out his old unfinished story and decided to rework it. According to Resnick, “I stuck Tarzan back in the jungle where he belonged, and kept the water.”

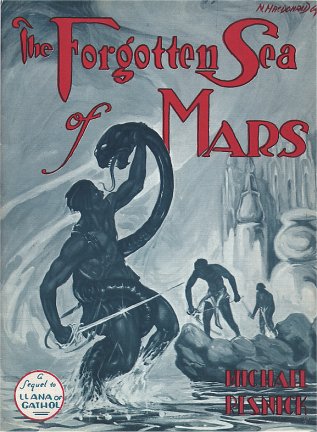

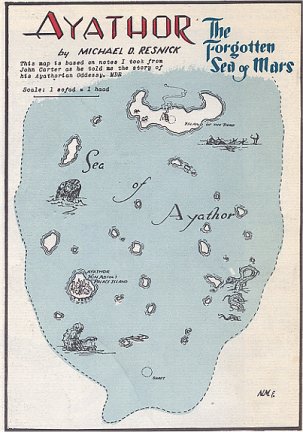

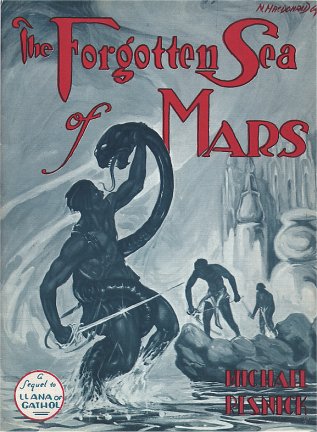

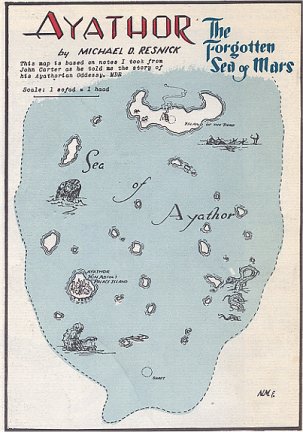

The resulting Barsoomian adventure (apparently sans Tarzan) was called The Forgotten Sea of Mars and it was presented as a sequel to Llana of Gathol. In 1965, Llana of Gathol would have been the end of the series. John Carter of Mars, the compilation of two tale end bits, ‘Skeleton Men of Jupiter’ and ‘Giant of Mars’ would not be out for a while. Is it any good? Beats me. But it is out there on the net, if you search hard enough. Or at least listings for it are. The manuscript is described thusly: “26 pp. Typescript facsimile in 2 columns. With 8 full-page illustrations by Neal MacDonald, Jr.; map by Resnick. 11x8¼. pictorial wrappers by MacDonald, stapled. limited to 1111 copies. First Edition.” Publication date is generally given as 1965, which implies Resnick was around 23 at the time.

Doing the math, that means that Forgotten Sea of Mars comes to somewhere between 20,000 and 25,000 words tops, and quite possibly less. Which means its just a big short story, or novella or novellette, whatever they’re called. Resnick seems to have been imitating the form that Burroughs was using in his later works like Llana of Gathol and Escape on Venus, not full-fledged books, but rather, a series of short adventures. Llana of Gathol was a four part sequence of loosely connected novellas or novelletes. Forgotten Sea of Mars may have played as a fifth wheel.

Of course, there’s the question of why did he bother? Why did anyone bother? And why wait almost ten years? Partly, of course, it’s the simple gap between the precocious fourteen-year-old and the more focused twenty-three-year-old.

But there was something else going on as well. Burroughs was a pulp writer. He had a good long run, being a raging success through the twenties and thirties. Into the forties, paper shortages started to impact the pulps. Paper got scarcer and more expensive, the age changed. Suddenly, the adversaries of Doc Savage and the Shadow were a lot less fascinating when we had real guys like Hitler and Stalin running around. America at war was a very different place.

The result was that Burroughs was falling out of style. Whole categories of writers, entire genres were literally vanishing or being substantially reworked. There used to be actual genres of Jungle Men, of Pirate stories, of Airmen. By the 1950s, most of these were gone. Burroughs was all set to fade into the literary obscurity.

What happened. Well, in the 1960s, what came out were mass market paperbacks. The pulp magazines were pretty much gone for good. The hundreds of newsstand magazines and serials had dwindled to a tiny handful, a dozen or less. But the mass market paperback was out and taking over like a storm. Publishers needed product, they needed reliable product, and they needed a lot of it.

And there was a lot of Burroughs product waiting to make a comeback. Indeed, more than anyone guessed. The Burroughs estate managed to jolt the marketplace with ‘new Burroughs’, finding and releasing unpublished or obscure work like Giant of Mars or Wizard of Venus. There was already a loyal fan culture, publishing fanzines, promoting. And of course, there were the comic strips and the Tarzan movies and television series. Perhaps Burroughs had never really left, when you think about it. But regardless, through the sixties and seventies, from say roughly 1963 to 1982, he was back with a vengeance.

The Burroughs boom was not alone. The sixties also saw a mass market revival of Doc Savage and the Shadow, who inspired their own harsher imitators in guys like Mack Bolan. Robert E. Howard’s Conan and H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu also stormed back in a big way. In fact, just about every pulp serial had at least a shot at a new lease on life -- I have a complete collection of Seabury Quinn’s supernatural detective, Jules De Grandin, in paperback. A lot of pulp writers, if they’d stayed in the game, found themselves experiencing a revival.

Some of it lasted, some of it didn’t. Lovecraft and Burroughs, arguably, managed to cling to some kind of permanent or respectable status. Doc Savage and the Shadow sank back into their pulp origins, victims of their own cliches. Conan became a franchise, and eventually faded away.

Writing and publishing, like everything else, has its own fashions. There were always new writers, new ideas, new changes to be rung. The Burroughs revival, the pulp revivals in paperbacks simply faded away as the good material was used up and eventually became stale, and publishers and writers built or moved past with new material. Not to say that there can’t or won’t be another revival further down the road. You never know.

But the point is that in the mid-sixties, Burroughs and Barsoom were hot, hot, hot! Which meant that fanzines were popular, a well-written fanfic would be extremely popular. Resnick returned to the Forgotten Sea of Mars in 1965 because Barsoom was huge. There was a community, a marketplace of sorts, a demand.

And of course (and I’m just speculating here), publishers were making money off of Burroughs and Barsoom. They were definitely in the market for something just like it. So a sufficiently brilliant and well received fanfic might lead a real publisher to give a promising young writer a shot... Especially if he was doing something sufficiently Barsoomian, perhaps especially a makeover of a Barsoomian fanfic.

Barely a year or two later, around 66-67, Resnick took the Forgotten Sea of Mars which was copyrighted to the Burroughs estate, and stripped all of Burroughs characters out. He transposed it to Ganymede, and kept a few plot elements.

The result was Goddess of Ganymede and its sequel, Pursuit on Ganymede. Ganymede itself is sometimes only a thinly disguised version of Barsoom. Almost all of the names for instance, have a Barsoomian cast to it. Instead of ocre moss, Ganymede is covered by a brown grass. Resnick at points refers to water being scarce upon Ganymede, and frequent dust storms, very Barsoomian indeed, although at other points, Ganymede seems quite a jungle covered place. There are other points of connect, which I’ll touch on later. Of course, the real problem is that Resnick’s two Ganymede novels come to about 120,000 words. Realistically, Forgotten Sea was no more than a fifth or sixth of that, so you won’t see more than shadows and whisps of Forgotten Sea in Ganymede.

What we have really, is an interesting sequence of the chains of inspiration and recycling that writers continually indulge, mining their old work and ideas, rewriting, rethinking. Resnick’s original unfinished Tarzan’s Forgotten Sea of Mars, his later published Forgotten Sea of Mars and his Ganymede novels, by his own account, derive one from another. By his own admission, each was mined to produce the next. But at the same time, each represented a radically different work, whle bearing the fingerprints and inheritance of its predecessor.

In another sense, we have a forensic of a young writer’s early career. Resnick’s juvenile first effort in the fifties went nowhere. But in the midst of a Burroughs revival in the mid-sixties, his fanfic found a place, and perhaps led to his first book contracts.

It’s tempting to suggest that it was Resnick’s breakthrough into writing and publishing. Perhaps it was. But after his third published novel, the Conanesque Redbeard he seems to have gone into anonymous (but profitable) adult novels and other writing. Was his work with Forgotten Seas and Ganymede really a gateway, did it open doors, give him enough credits or experience to go down that route? Was it a hindrance? Or was it irrelevant? I dunno. My own view is that it probably wasn’t irrelevant, it was a credit, and when you’re starting out, you push your credits and credentials to the max, no matter what. It’s entirely possible that Resnick would have found his way onto a similar career path without Forgotten Seas and Ganymede, but so what? This was the path he walked.

It also illustrates how closely careers are tied to the fashion and techniques of the times. Burroughs was a creature of the pulps era, and revived by the paperback era. Resnick came along at the right time to start his career, and when and where he came along shaped that career. Ten years earlier, ten years later, Forgotten Seas might have passed without a ripple, and there might not have been any Ganymede novels. And then where would Resnick be?

Consider my case. I do these essays for fun and for the amusement of a small group of people. They’ve been called brilliant at times. But it’s not going to get me anywhere. Donald Grant might have bought Ganymede on the basis of Forgotten Sea. But the modern Donald Grant wouldn’t be looking at anything but a restraining order to make sure I didn’t come within a thousand yards of him. I make no complaints, I do these things because I enjoy them, the fact that once in a while someone else likes it is a bonus, and it’s a pleasant enough way to sooth a keyboard until a real opportunity comes along. It’s a different time, different place, different circumstances.

Of course, ten years earlier or ten years later, Resnick might have gone on to a successful writing career, or maybe not. But the paths he took would have been assuredly different.

Now, just one more stop, and then its on to Ganymede.

FORGOTTEN SEAS OF MARS, SYNOPSIS AND TRANSITION TO GANYMEDE

Interior Art by Neal Macdonald, Jr. Bill Hillman was kind enough to photocopy a partial copy of the Forgotten Seas of Mars for me, which allows me to review and synopsize it, and to examine it for its contributions to Resnick’s Ganymede.

Still the blade came ever closer

The ulsio leaped with a horrid scream

I tried to draw my swordThis version, published in 1965 under copyright of the Burroughs estate, doesn’t have Tarzan in it. Rather, it’s a very straight, very straightforward John Carter/Barsoom story, aping Burroughs conventions, right down to the framing sequence of the remarkable interplanetary visit from John Carter who tells the adventure.

The novella is billed as a sequel to Llana of Gathol, Burroughs ‘penultimate’ Barsoom book. Actually, Llana was originally published in magazines as a series of four interconnected novellas, picking up characters and plot threads from each other, and then later republished as a book, the tenth and apparently final Barsoom Book.

There was a fifth, completely unrelated, novella, Skeleton Men of Jupiter which came out later, and an odd little bastard piece called John Carter and the Giant of Mars which started out life as a Big-Little Book, eventually got tuned up for magazine publication. These two pieces in the 60s were tarted up together and released as an eleventh Barsoom Book, John Carter of Mars, that never got much respect.

For all intents and purposes, for most fans in the 50s and 60s, the series ended with Llana of Gathol.

But Burroughs had left a major loose end. Tan Hadron of Hastor, hero of A Fighting Man of Mars had featured in the third novella, and the beginning of the fourth, but then, unaccountably, had been dropped or misplaced. Llana of Gathol ends with no hint of Tan Hadron’s fate.

This is what Resnick picked up for a fifth novella. Where was Tan Hadron? John Carter’s forces search, but to no avail. Finally, Carter receives a message to come alone to Zodanga. It’s obviously a trap, but Carter, the big lummox, decides to walk into it with no precautions and no follow up.

There he encounters Rab-Zov, the villainous henchman of Hin Abtol, seen in Llana of Gathol. From this unsavoury character, he discovers that Hin Abtol... the running villain of Llana is on the loose again and scheming for world conquest. (This is a pretty good trick, since Hin Abtol was John Carter’s prisoner at the end of Llana, but hey, let’s allow some license here.) He also learns that Tan Hadron is being kept a prisoner in Hin Abtol’s back up kingdom - a buried sea at the north pole, companion to the south pole’s Omean, called Ayathor, where Abtol has another half million warriors frozen in ice. Then the trap springs shut as Rab-Zov’s men descend upon John Carter.

Okay, at this point, let me say that the Tan Hadron gambit is an excellent starting point, recycling other characters from Llana also works nicely. Even the postulate of a counterpart to Omean at the north pole makes a bit of sense.... After all, wouldn’t the same forces that produced Omean at the south pole also produce a buried sea at the north pole?

On the downside, the story requires John Carter to be.... Well... stupid, at several points in the novella. Look, Llana of Gathol begins with John Carter essentially on a sightseeing trip, when adventures start happening to him. Early on, he just wants to get back to Helium, raise a fleet, and put a stop to all of this nonsense, but circumstance keeps getting in his way. In Swords of Mars, he goes undercover on a personal mission. Neither novel requires Carter to be actually stupid.

In truth, the fact is that John Carter is not stupid, and that shapes much of the Martian series. After he becomes Warlord of Mars, he can raise entire fleets to solve his problems, and has no hesitation doing so. This is why Burroughs shifts his narrative to other characters - Ulysses Paxton, Carthoris, Tan Hadron, Vor Daj, Gahan of Gathol. All of these guys have to work for a living, John Carter doesn’t. Instead, John Carter in several of these novels becomes the Deus Ex Machina, he’s the guy who shows up with the fleet to settle everyone’s hash.

Unfortunately, for Resnick's story to work, John Carter has to be not only stupid, but recklessly stupid. It’s one thing to take a calculated risk to meet Rab Zov in Zodanga. But not to have any assets in place there? Not to have any back up to help rescue him from what he knows is a trap?

He fights his way out of the trap, jumps in a flyer, and zips off to the north pole, with no plan, no ideas, and only the vaguest idea that the underground sea is located in the north pole region. He sees matters as urgent, he has to get to the north pole before Rab-Zov, but truthfully, he’s going off half assed and in a way that will blow any advantage he has over Rab-Zov. It might have been better to follow the villains back to the lair, or perhaps go back to Helium and have a fleet scour the place, or have his agents scour the libraries of Panar. Again, its John Carter being visibly stupid in a way that I don’t really associate with Burroughs.

Amazingly, he finds the entrance to the buried sea through dumb luck. He flies in there, covered with pigment disguising himself as a red man. Then he proceeds to try and infiltrate Hin Abtol’s headquarters by hiding his flier, ditching his weapons and swimming over. There’s a couple of daring battles with sea creatures along the way. But John Carter is immediately captured because he didn’t realize that his red pigment would wash off in the swim. Honestly!

Yes, I know that Burroughs occasionally had his characters do stupid things. But (1) It wasn’t really acceptable or good writing from Burroughs; (2) He was still Burroughs and could occasionally get away with that crap, imitators get even less slack.

After that though, things improve markedly. Taken prisoner, Carter makes a friend of a Panar officer named Bal Daxus, and an enemy of another Panar officer named Talon Gar. Through his friendship with Bal Daxus, he learns of Dox’s infatuation with a Panar beauty named Lirai, another prisoner and the object of both Hin Abtol’s and Talon Gar’s lusts. Carter resolves to help the hapless lovers. Best of all, he finds himself cellmates with Tan Hadron.

Hin Abtol makes an appearance and sentences John Carter to death in his diabolical chamber of madness, an ordeal that very nearly does Carter in. But through courage and wits, Carter manages to escape. From there, he enlists Bal Daxus, rescues Lirai and frees Tan Hadron. However, while their backs were turned, the evil Talon Gar makes off with Lirai, so there’s nothing for our trio of heroes to do but follow them.

This takes them to the Island of the Dead where they discover a lost race of wrinkled, apparently ancient dwarves. These guys are out of touch. Religious fanatics, they worship a sky god, Zar, who lives above the dome of the world and who is responsible for creating everything in the universe. At first, they’re pleasant, but their fanaticism takes on an unpleasant edge, when they force the four male warriors to fight to the death for the honour of being embalmed as part of their ‘Treasure’ of exquisitely preserved corpses dating back to the O-Kar inhabitants. Here, Talon Gar meets his fate at the end of John Carter’s sword. Luckily, Carter and his friends are able to take advantage of the dwarves mad fanaticism to overcome them and escape.

Then they return back to Hin Abtol’s fortress, still at large, where they come up with a brilliant scheme to liberate the half million frozen warriors that Hin Abtol has tucked away, and overthrow the would-be tyrant. Rab Zov and Hin Abtol shortly thereafter meet their fates, Bal Daxus is acclaimed the new Jeddak of Panar and Ayathor, and everyone lives happily ever after.

So that’s the story, I’ve spoiled it for all of you. Although, on the one hand, its published in 1965 so its now 42 years old, so I think some statute of limitations ought to apply. And on the other hand, its such a rare and arcane piece that 99% of you will never get a chance to read the original story and this is as close as you’ll ever get.

My carping about certain plot driven illogicalities in John Carter’s behaviour notwithstanding, how does it hold up?

Well, I’ll leave it to the pithy words of the respected J.G. Huckenpohler who said it was among the finest pieces of Barsoom fic ever written. High praise from a man who knows what he talks about.

And to be fair, it is very well done. Resnick captures John Carter’s voice, that earnest mixture of humble bragging and easy-going killing machine, quite well. The voice is a very familiar one and it rings true. The action sequences are effective and exciting, his descriptions both of Hin Abtol’s fortress and the Island of the Dead are visceral and evocative.

She lifted a dagger from the corpse's harness

I commenced to take Talon Gar to piecesIt is remarkably consistent with what we know of Burroughs Barsoom - for instance, the taxidermy efforts of the Island of the Dead, have been seen several times before, with the embalming practices found in Manator, in Horz and in Korvas. Ayathor’s islands are presented to us as re-inhabited ruins - the structures originally built and abandoned by the O-Kar before they established their domed cities, now overrun with vermin and wildlife, work effectively.

The parts that Resnick embroiders - Ayathor, the forgotten sea itself, as well as its name, the race of Zar worshippers, the beastial Targaths, all seem very consistent and naturally flowing from established Barsoom.

In short, quite a superior piece of Fanfic.

So, how much of it makes its way into Resnick’s Ganymede?

Not as much as you might think. The name of Talon Gar is recycled of course, though on Ganymede, Talon Gar is a heroic prince of Rombus. The despicable qualities are given to a villain named Savus Vir. Resnick has a throwaway reference to a small ocean in the northern hemisphere of Ganymede which may have been an echo of Ayathor.

The most direct transposition is the Chamber of Madness scene in Lost Sea of Mars which is recycled almost word for word in Goddess of Ganymede. The two play just about the same, although John Carter definitely gets the worst of it, and the beastiary is re-arranged.

The scenes with Lirai in the tower echo the scenes with Delissa in the tower. And there’s a loose correspondence between John Carter’s encounter with the fanatic dwarves of the Island of the Dead, and Adam Thane’s encounter with the fanatic cannibals in Pursuit on Ganymede.

There are other shared plot points here and there, but mostly these are generic plot points, not particularly specific to either Ganymede or the Forgotten Sea.

And of course, there’s the Targath. In the Forgotten Sea, the Targath is described thusly:

"A most ferocious beast. It stands about eight feet tall and has a large muscular body which is covered by tufts of long, gray hair. Like the white ape, it has an intermediary set of limbs which can be used as either arms or legs.... I was greeted by a most horrible sight. I knew at once that I was looking at a targath, for those protruding fangs and that eyeless head could belong only to the creature Tan Hadron had described to me.... His movements brought to mind the picture of a giant sloth, but in appearance he was unique. No words can adequately describe that unseeing face, those great patches of long gray hair, the sheer brute power of his nine foot frame."Okay, so basically, the Targath seems to be little more than a dwarf form of the Great White Ape. Dwarfed because Resnick actually took a look around and realized how unrealistically exaggerated a fifteen foot height would be. In this, I’ll give him compliments, since I’ve always been uncomfortable with the sheer scale of both the Great White Apes and Green Men - a scale that doesn’t seem to jibe with either their weight or Carter’s or other people’s fighting prowess against them.There’s an indication that they’re aquatic or semi-aquatic. It appears that one of the unseen monsters Carter battled while swimming in Ayathor might have been a Targath. The eyelessness suggests that Resnick is telling us that they are creatures of lightless caverns. The reference to gray tufts of fur suggests to me that Resnick was also influenced by George Pal’s depictions of Morlocks in the Time Machine movie.

Targath’s also show up repeatedly in both Ganymede books. The scream of a Targath is heard outside the walls of Kroth as early as page 26. On page 116 we finally get a description:

"I beheld a most awesome beast. It was perhaps the size of a gorilla, and it walked upright, but there all similarity ended. Four taloned armps sprung from its massive torso, and its body was covered with thick tufts of yellow hair. Its face had no ears or nostrils, but by far the most gruesome feature was the eyes. They were great albino things, glowing a dull white and covering fully one third of the face. One could never tell where those eyes were looking, for neither pupil nor iris were discernible. The shape of the head resembled that of a frog, with the exception of the protruding jaws, which exposed row upon row of long pointed fangs, whenever the Targath snarled. .... I was taken aback by the beast which confronted me when the twelfth door opened. It stood fully eight feet high and I could hear its growls as it approached... A yellow apelike animal."Same size, same number of limbs, same apelike frame, same long tufts of fur. The Ayathor-Barsoom Targath and the Ganymede Targath are clearly not the same species, but they’re definitely closely related to each other. Closely enough to obviously share a name. Of course, Ganymede is not a lightless cavern world, so the eyelessness had to go, and the colourlessness as well. And Ganymede is more land than sea, so the Targath’s amphibious quality drops away. But for all of that, they’re clearly the same or closely related beasts, and therefore related in turn to White Apes and Green Men.There are a couple of other Ganymedan creatures, notably the Karix and the Tragor which don’t appear in The Forgotten Sea of Mars, but would have fit right in. The Karix is a large predator whose eyes lack pupils and are permanently adjusted for dim light - daylight or any other light blinds them because they cannot adjust for it. The Tragor is a giant eyeless bird which perceives by echo-location, oddly, there’s no need or requirement for a sightless bird on well lit Ganymede. So I’m inclined to wonder if perhaps these creatures date back to some earlier, perhaps original, draft of the Forgotten Sea.

Adam Thane, the protagonist, displays a very Tarzan-like tendency to take to the trees when travelling. Thane is an archaic noble title, as you’ll recall from MacBeth. Shades of Lord Graystoke. Interesting considering that Tarzan seems to have been dropped from the second version of Forgotten Sea but was very much a part of the original inspiration. Delisse, the heroine, is phonetically mildly suggestive of Dejah Thoris.

The reality is that while the Ganymede novels run 120,000 words, Forgotten Sea is a mere 20,000. Obviously, with the transposition of setting from an underground sea and its island ruins on Barsoom, to a complete otherworld on Ganymede the setting and the story which evolves changes dramatically. Drop out Tan Hadron, John Carter and Hin Abtol, and the story changes even more.

The two are clearly and obviously separate works. Ganymede may take some bits and pieces from Forgotten Sea, and its clearly an inspiration, but it is its own creature.

AYATHOR, THE FORGOTTEN SEA: POSTSCRIPT

Ayathor, the northern underground sea, or forgotten sea of Mars, was almost certainly formed at the same time as Omean and by the same process. For the record, you can take a look at Matching Mars, the Poles, at this URL: ERBzine 1503

It was an awesome sight

.

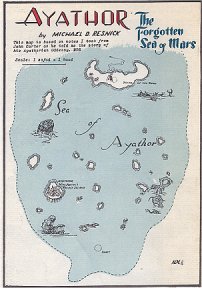

Ayathor Map

Art by Neal Macdonald

I pursued Him Abtol

with great leaps and boundsRoughly 3.5 billion years ago Mars was hit by a pair of titanic impacts which created the Argyre and Hellas basins and reshaped the geography of the planet. The Hellas impact alone blasted enough debris it cover the united states to a depth of two miles. While the debris from these enormous blasts created huge broad rings of highlands around the impact sites, some of the debris travelled vast distances, to the point where their falling points were affected by the planet’s rotation. Debris falling along the swiftly moving equator tended to spread out and smear, of course. Debris falling closer to the poles tended to build up and concentrate because the poles were comparatively stationary.

Omean was formed at the south pole when the small existing polar cap was literally covered twice with a mile thick shell of fused and semi-melted rock. The heat and pressure eventually liquefied the frozen buried ice cap, resulting in an archaic underground sea at the south pole.

Ayathor’s formation was similar, except that comparatively far less material covered it. Both the Hellas and Argyre impacts were in the southern hemisphere, hence a great deal of debris wound up falling and concentrating on the south pole. Material falling on the north pole had to cross the equator and travel a much greater distance. The volume falling upon the north pole was perhaps 25% of the south. MAP 1 | MAP 2

Given that Ayathor is likely nearer to Panar than the Okar cities, we would probably locate it under the small central highland area of the pole, which separates the two cultures.

The result was a thinner covering shell, and a smaller buried sea. Or perhaps more than one buried sea, with the thinner cover collapsing at different points to divide the pole into sub-seas instead of the single large sea that Omean became. At this point, we have no evidence for other sub-seas at the north pole.

The comparatively thinner shell meant that Ayathor was not quite as isolated as Omean. It probably retained cave connections to both the surrounding polar sea and to land/air.

Indeed, there is a great deal of evidence that this was the case. Ayathor’s waters possess substantial populations of fish, serpents and other sea or amphibious creatures. John Carter is twice attacked by serpents and other menaces while swimming, and Hin Abtol’s fortress population subsists on fishing, as presumably, do the inhabitants of the Island of the Dead.

The point is further reinforced by the fact that the sea was colonized by the O-Kar. We know that the O-Kar culture did not have flyers until comparatively recently, and it seems unlikely that they had flyers at the early point in their history where they colonized Ayathor. Most likely the O-Kar reached Ayathor through passages linked with the Carrion caves.

Similarly, the Targaths and Ulsios which currently occupy islands in Ayathor could only have reached the Forgotten sea by travelling through cave passages. It seems unlikely that these dangerous creatures would have been imported by the O-Kar. Indeed, the Targaths appear to be highly adapted to the forgotten sea to the point of losing their eyes and becoming semi-aquatic, which suggests that they were there long before the O-Kar. It’s likely that if they had been imported by the O-Kar, they would not be quite so thoroughly adapted to the environment.

The presence of cave connections suggests that Ayathor may have undergone some drainage or evaporation. On the other hand, these cave connections also imply that Ayathor’s waters may have been somewhat replenished by glacial ice water. However, the exterior processes of evaporation of the outer seas may well have lead to the collapse of many of the cavern connections. It’s possible that while there are likely still a few cave connections, Ayathor is far more isolated than it used to be.

But this takes us to a series of questions about the forgotten sea. How does it sustain life now? How did it sustain an O-Kar culture and what happened to that culture?

As we’ve noted, clearly Ayathor sustains life. But it lacks sunlight and therefore it lacks the fundamentals for life - photosynthesis. On the other hand, Ayathor is not an underground ice cube, but rather, its water is liquid and its climate is quite warm. It’s likely that Ayathor is being geothermally heated, possibly from the stresses of coriolis forces at the polar region, although we have evidence of at least some residual volcanism at the Island of the Dead.

This geothermal energy/residual volcanism is the basis of the Ayathor ecology. Lacking photosynthesis, the basis of life is probably extremophile bacteria on the sea floor, using geothermal heat to metabolize minerals. From there, microscopic diatoms feed on the bacteria, moving on up to sea life and fish.

The energy available from geothermal synthesis is almost certainly much less than from photosynthesis which suggests that the pace of life is slower. Reports suggest that the seas of Ayathor abound with a rich harvest of fish. But it is likely that these fish are long lived and slow growing. Overfish, and it would take the fish population a long time to recover.

This might be a factor in the abandonment of Ayathor by the O-Kar. They may simply have assumed that stocks would replenish themselves at the same rate as on the surface, depleted their food supply and were forced to leave or starved when these food supplies failed to regenerate quickly.

Of course, we’re speculating on the extremophile economy. We note that Hin Abtol’s island has a very large, extremely aggressive population of Ulsio’s and Targaths. These higher animals obviously have a far more energetic metabilism. A large population of these creatures suggests a much more active biology, which implies that the extremophile geothermal-synthesis ecology may be as productive or more productive than the photosynthesis based ecology.

But we don’t know if this is actually the case. The Ulsio’s and Targath’s high population may not be normal. Rather, it may be that the recolonization by the Panars, and the introduction of humans and their supplies may have triggered a population explosion among Ulsio’s and Targath’s.

We note that the Ulsio’s are extremely aggressive, attacking even groups of armed humans. Is it possible that the Ulsio’s aggression is borne from starvation resulting from a human triggered population explosion?

It is clear that Ayathor was once inhabited. Indeed, at least some parts of it still are. Hin Abtol’s base appears to have been initially a large and substantial city constructed by the O-Kar on an Island. The size and degree of elaboration of the city suggests that the O-Kar lived there for a long time, perhaps several generations. It’s likely, given the degree to which this Island was built up, that many or most of the other Islands were inhabited as well.

Yet with the exception of the Island of the Dead, it appears that the Sea was abandoned. Why was this?

It doesn’t seem likely that the O-Kar would have simply abandoned it for their domed cities. It’s clear that they made a substantial investment in living in Ayathor, and even when their domed cities were constructed, its likely that a population would have remained.

It’s more than possible that cave ins, earth tremors or even warfare might have blocked Ayathor from the rest of the O-Kar communities, with the result that it would have been permanently lost and eventually forgotten. But even then, we’d expect a resident O-Kar population to go on living there.

So what happened? We can only guess.

One possibility is simply resource depletion. The O-Kar eventually fished out the sea and found the stocks were not replenishing. They starved to death, their culture collapsing in cannibalism, the last survivors becoming food for marauding ulsio’s and targaths.

Another possibility is that the environment was cumulatively toxic. This isn’t out of the question. An underground sea’s waters are undoubtedly highly mineralized, and some minerals can build up in the liver and kidneys, in the brain and in fatty tissues, becoming toxic and even potentially fatal. Premature aging, senescence or mental problems, sterility or birth defects might have become problems. This might have caused the O-Kar to voluntarily abandon Ayathor.

It appears from the sophisticated state of the ruins that the O-Kar lived several generations in Ayathor, so if there were issues of toxicity, they may have been very slow accumulating. Or they may have resulted from a transient phenomenon, perhaps geysers or a minor volcanic episode, or some other event causing a ‘toxic bloom.’

One argument for toxicity is the condition of the sole known surviving indigenous population, the Inhabitants of the Island of the Dead. John Carter describes them as ‘wrinkled dwarfs’ apparently greatly aged with no youthful seeming persons among them. Their behaviour reeks of irrational religious fanaticism. Is their madness and aged and withered appearance the result of long term living in a toxic environment?

John Carter considered them to be a childless population of immensely old people. In fact, they might have been comparatively young, and their stature and withered condition might be a result of environmental toxicity. Of course, notwithstanding their condition, they appear to remain as a viable population.

It might be that the O-Kar vanishing was attributable to a variety of factors - warfare or cavern collapse cut the Ayathor population off from the outside, and from the supplemental resources that they depended upon. Cut off from the outside, they could only rely upon the resources of the sea - and quickly began overfishing, which also resulted in the build up of toxicity in their tissues. The fishery collapsed, the society was undermined by toxic poisoning and began to starve, the O-Kar resorted to warfare and cannibalism, plummetting ever downwards until the last few survivors were eaten by Targaths and Ulsios.

So, how did the inhabitants of the Island of the Dead survive, when the O-Kar went extinct everywhere else in the sea?

I think the key is in the ancient O-Kar culture. It appears that the O-Kar, or at least, these O-Kar, shared important aspects of their culture with the Orovar.

The most important being Ancestor Worship carried to the point of ceremonial funerary preservation. The ancient Orovar, and apparently the O-Kar, set great store by the careful preservation of their dead. We see this in the mortuaries of Horz in Llana of Gathol. John Carter also encounters similar preservation in the dead city of Korvas in the Giant of Mars. Gahan of Gathol and Tara of Helium encounter a live mortuary tradition in Manator in Chessmen of Mars. Gulliver Jones, in Arnold’s novel, also encounters a living mortuary tradition, coupled with a ‘river of death’ among the white-skinned Hither People of Mars. So its pretty well established.

This allows us to understand what the Island of the Dead really is or was. It was the central necropolis of the Ayathor culture. It was where they Ayathor people brought their dead for ceremonial mummification and preservation. In this, the Ayathor seem to have been different from the cultures of Horz and Manator who seem to prefer to keep their preserved dead close by. Instead, the Ayathor (perhaps because living on Islands, space was at a premium) preferred to concentrate their dead in a necropolis or a designated ‘Island of the Dead.’ Far from being creepy, it was probably a highly treasured religious and ceremonial island. Indeed, it was one of the largest, if not the largest islands in the sea of Ayathor, clearly marking its importance.

So what happened? Very simple. As the Ayathor culture began to succumb to collapse - internal warfare, starvation, toxic poisoning, they continued, at least initially, to send their honoured dead to the Island. As food supplies collapsed, and civilization fell apart and cannibalism ran rampant, the Island of the Dead became the sole surviving larder.... Literally, the inhabitants of the Island survived by eating the generations of their ancestors corpses. Protected by the sea, the inhabitants were well fed and organized enough to slaughter the occasional group of starving refugees or marauders who managed to get it together enough to get on a boat.

The eating of the dead allowed them to survive the population collapse that stripped the rest of the sea of human life. After the population collapse, they supplemented their diet by preying on the remnants of humanity, and on the now starving ulsio and targaths on the other islands. And within a reasonable period of time, the sea life had regenerated enough to support the tiny relic population remaining on the Island of the Dead.

Of course, cannibalism takes its psychic toll, leading the inhabitants to embrace an irrational religious mania. They were the only survivors of an entire sea-wide culture, clearly they were favoured by God. The corpses that sustained their lives were doubly venerated, no longer as ancestors, but literally as manna from heaven - gifts or treasures from God. The uneaten corpses became treasures, literally, the treasure of God. The existence of a world beyond the sea was dismissed, the existence of a past beyond the present was equally dismissed. The inhabitants of the Island of the Living Dead simply could not psychically afford such notions. It’s one thing to eat a treasure or gift from God, God wants you to eat it. It’s another to eat the corpse of a beloved ancestor or someone’s beloved ancestor, that’s a blasphemy. Cannibalism meant that the past had to be expunged, they could admit no historical connection to their dinners. They could acknowledge no world beyond, because they couldn’t intellectually go where those notions lead.

Of course, none of this mania was helped by the likely accumulation of toxins in their bodies and brains.

This also clears up the reception and treatment that Talon Gar’s and John Carter’s parties received when they reached the Island. They were welcomed as gifts of God. Essentially - boxed lunches. The finest of them would be added to the permanent or long term treasures of God. This probably echoed the selection process during the cannibalism period - they would have preferred to eat the poorer and less attractive preserved corpses, and to avoid the noblest and most imposing. Those who didn’t make the grade, who died in battle... Well, they were going to be fresh lunch. Talon Gar, who died on the Island, probably became a banquet item after John Carter and his friends left.

The survivors of the Island of the Dead continue to worship a ‘sky god’ who lives beyond the rock dome which is their ceiling or firmament named Zar or Sar. As we saw from Otis Adelbert Kline’s Outlaw of Mars, ‘Sar’ or ‘Sarkiss’ appears to be an alternate name for the Sun God. Tolstoy’s Aelita: Princess of Mars also gives us Sar or Soat-sar as the Martian word for Sun. Lin Carter’s Martian novels give us Zha as a word-root meaning fire. What this tells us is that these people seem to be engaging in a form of Tur worship.

Which explains ‘Ayathor’ the name. Ayathor, like so many of Burroughs Barsoomian place names, is Tur derived. It’s actually, or originally, Aya-Tur.

And what does Aya mean? Well, looking through Huck's Barsoomian glossary, the only appearance of ‘Ay’ or ‘Aya’ is in Ay-Mad, which is the name of a Hormad, given as ‘Number One Man.’ The Green Men have a term ‘O-Mad’ which means ‘One Man’ or ‘Single Man’ to refer to a person who has only one name and who has not made a kill. So, from these we can infer that ‘Ay’ and ‘O’ share a category of meaning which refers to ‘first’ ‘singular’ ‘unique,’ ‘source’ or ‘one’ or the ‘number one.’ We know that the suffix ‘a’ seems to denote feminine or female, perhaps daughter, perhaps fertility.

Which suggests that Aya or perhaps Oa or Oya, means something along the lines of ‘first - feminine’, or perhaps ‘source-daughter’ or perhaps ‘singular-fertile.’ Taking a leap, in context it might mean sanctuary - a fertile refuge, the sole place of safety and life.

Therefore, Ayathor probably means something close to “Sanctuary of Tur” or “Sanctuary of God.” This fits in that it appears to have been the first refuge of the fleeing O-Kar as they were constructing their domed cities.

An update from Mike Resnick. I wrote THE FORGOTTEN SEA OF MARS in 1963, when I was 21 years old, at the request of Vern Coriell, who was editing the Burroughs Bulletin. He sat on it for 2 years, so I pulled it back and gave it to Camille Cazedessus Jr., editor/publisher of ERB-dom. Had Vern not initially requested it, the novella would never have been written.

The real story behind

THE FORGOTTEN SEA OF MARS and the GANYMEDE books.I met Don Grant at Tricon, the 1966 Worldcon. He'd seen THE FORGOTTEN SEA OF MARS and told me if I'd lose the copyrighted characters but keep the plot as part of a novel, he'd buy it. And he did.

Paperback Library then contacted me amd offered a 2-book contract, for THE GODDESS OF GANYMEDE and a second GANYMEDE book (which I'd already written: PURSUIT ON GANYMEDE).

I had no illusion about the quality of these things. I wrote the pair of them in less than two weeks, while holding down a full-time editing job. I wanted to use a pseudonym -- I didn't mind 400 ERB fans (Grant's hardcover print run) knowing I wrote them, but I didn't want 100,000 people thinking these books, which I ground out for filthy lucre, were typical of what I could do. They said No, that GODDESS was already copyrighted in my name, and they were using my name.

I did one more grind-it-out-for-cash job, REDBEARD, in 1967, though it didn't come out until 1969. Then one day I was in New York, having lunch with Lin Carter. He told me he had just finished a Leigh Brackett book, and was embarking on an ERB book, and had just signed to do a Robert E. Howard book. I asked him when he was going to do a Lin Carter book. He just stared at me, as if the question had no meaning to him -- and in that instant I realized that I didn't want to grow up to be Lin Carter, spending my whole life copying other writers' styles and ideas.

I stayed away from science fiction (as a pro, not as a fan) for eleven years, long enough (I hoped) to give people time to forget those three books. (Didn't quite happen; they still come back to humiliate me at autograph sessions.)

I still get offers every year from publishers who want to bring the Ganymede books back into print. I will never allow that to happen, and I myself have not opened either of them in 45 years.

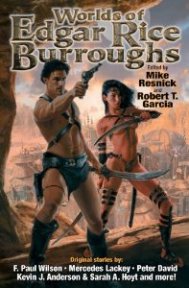

There is nothing wrong with Edgar Rice Burroughs. In fact, THE WORLDS OF EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS, an anthology I co-edited, will come out from Baen Books this October. What was wrong was trying to write like Edgar Rice Burroughs instead of like Mike Resnick.

Since 1980 I have written only Resnick books and stories, and I think the record speaks for itself: 71 novels, 260 stories, 3 screenplays, editor of 41 anthologies, and according to Locus I am the all-time leading award winner, living or dead, for short fiction.

-- Mike Resnick

|

Edited by Mike Resnick and Robert T. Garcia Original theme anthology.

Available at bookstores and

|

|

Den Valdron's "Ganymede or Bust" Series

|

1. Tarzan On Mars |

2. Forgotten Sea of Mars |

3. Mike Resnick's Ganymede |

4. Ganymede: Two Universes |

5. Resnick's Ganymede II |

|

for Den Valdron's Fantasy Worlds of ERB |

WEBJED:

BILL HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

All

ERB Images© and Tarzan® are Copyright ERB, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2007/2019 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.