CHAPTER XVI

All were busily engaged day by day in preparing for defence. Entrenchments

were made round the house, with here and there a stockade. It was cruel

to see the beautiful flowers uprooted, and fruit trees cut down, but ruthless

as it seemed it was a stern necessity. The house itself was loopholed,

and sandbags placed on the parapets, from behind which the defenders could

fire in comparative safety. Yunacka was here, there and everywhere, and

occasionally took a spell at digging. Several natives suffered from his

pranks, as he would insist in shovelling the earth about in all directions,

sometimes over their heads and backs.

Harry’s first effort was to drill him so that he might get accustomed

to handle a gun. By signs he made him look at him, while he went through

the exercise. The wild boy squatted on his haunches, and watched him with

interest. Harry then handed him a rifle, which Yunacka handled very gingerly,

trying to peep down the barrel. The drill was a source of amusement to

the others. When Yunacka was tired he would climb a fruit-tree and regale

himself, regardless of expostulations. It was wonderful how intelligent

and docile he became at last, although still full of fun and mischief.

In the middle of a lesson he would throw his rifle down to chase some pilferer

of a monkey.

To get him accustomed to the sound of firing, a pistol with blank cartridge

was placed in his hand and his finger put on the trigger. When the pistol

went off he turned a somersault. He smelt the burnt gunpowder, put his

finger into the barrel, and then placed it to his lips. A few rounds steadied

him, and he then seemed anxious to fire repeatedly. It was wonderful how

soon he became a marksman.

His intelligence was developing daily, and he began to look more and

more like a human being. He was also taught to wash himself. The party

were soon busy in making cartridges, casting bullets, etc. The cannon were

dug up and found to be in capital condition. It was hopeless to attempt

making many cannon balls, but they managed to provide themselves with a

lot of grape-shot. They knocked up rough carriages under Clarence’s superintendence,

and mounted the pieces on them. In the evenings Clarence and Dana sang

duets together, much to Val’s disgust.

“Wait till I get home again,” he said to Harry; “I’ll learn singing,

and lick that Fitzhugh into fits.”

The messengers returned with news of the mutineers, who were slaying

and pillaging not very far distant. As he had drilled Yunacka so well,

Harry was entrusted by Fitzmaurice with the task of drilling the servants,

which he willingly undertook. One day they received intelligence that a

party of mutineers were advancing, and might be expected at any moment.

Fitzmaurice had buried his valuables in the garden, so that the insurgents

were not likely to get much. The provisions were to be doled out in rations

when the siege commenced. The greatest drawback was in the only well being

exposed.

This was a serious matter; but they were prepared to face all risks

rather than give in. It was dreadful to contemplate Dana’s fate, poor girl!

at the hands of such wretches. The messengers had brought newspapers, from

which was gleaned horrible details of rapine, murder, and other matters,

which made them sick with horror, while it made the blood course through

their veins in their desire to be avenged. Human tigers were approaching

the jungle home, and they resolved, one and all, to defend it. It is such

desperate courage that makes heroes of men.Val and Harry were to take their

places among men, and acquit themselves bravely. They resolved to die with

their faces to the foe, and not like cravens.

Most boys of their age were at school; they were to attend another and

a sterner school, in which to learn what human endurance and suffering

were. A look of determination was on every face — even on Dana’s. Yunacka

had got used to the sound of firearms, and would prove a wonderful help.

Harry suggested to Fitzmaurice to try the cannon with blank ammunition,

just to see that everything was right. He consented, and the roar of guns

was heard for the first time in the heart of the jungle. Notice was brought

that the enemy were in sight, and among them one of Fitzmaurice’s own people

who had turned traitor. This man appears to have nurtured spite and resentment

in his heart against Fitzmaurice, because he had punished him for misconduct.

It was evident the fellow had lured the mutineers to the jungle home,

promising them a rich booty, and an easy conquest. His name was Baboo.

He had insulted Dana, and had received a well-merited thrashing. Just as

they received this intelligence Val and Harry were gladdened by the sight

of Golob, the shikaree, or native huntsman. The fellow had been sent by

their friends to find them, and had come on the scene at this critical

juncture. He was a splendid shot, was full of resource, and would prove

invaluable to the garrison. The brave fellow was appointed to command the

servants, under Fitzmaurice, of course, who was commander-in-chief. The

Europeans had assembled on the roof of the house to watch for the foe.

“There they are,” said Fitzmaurice, putting down his field-glasses;

“and I am sorry to say they have a field-piece with them, a six-pounder,

so far as I can make out.”

Several men on horseback were of the party, which numbered some two

hundred or more. This was fearful odds, but none thought of that for a

moment. Their faces were pale, but their hearts quailed not. As soon as

they came in sight their officers reconnoitred, while the men laid their

field-piece.

“Now then, lads,” said Fitzmaurice, “give them a taste of our quality.

Pick off the officers and gunners; we must draw first blood.”

They fired, when one of the rebel officers and several men bit the dust,

at which the defenders cheered lustily. Dana’s face was pale, but it was

relieved by a beautiful rose blush.

“Down for your lives!” said Fitzmaurice; “they are going to return the

fire.”

They obeyed, and the next moment the rush of a round shot over their

heads, within a foot or so, told them that the battle had commenced in

real earnest.

CHAPTER XVII

From behind their sandbags the defenders kept up a destructive fire,

Dana doing more in the work of death than any of the others. Each time

her rifle was fired a foeman fell, never more to rise. What a picture was

presented by that young and beautiful girl, not yet out of her teens, fighting

bravely in defence of her home. The native contingent could not do much

as yet, for the enemy were not visible to them. Yunacka was as restless

as a hyena, walking hither and thither as if he wished to take part in

the fight.

Getting impatient at last, he climbed a tree, from which he blazed away,

chattering, grinning, and patting his rifle as if it were something to

be proud of. Finding the rifles of the defenders did terrible execution,

the enemy retired to a safe distance, having done little or no damage beyond

sending a few round shot through the house. The defender had a breathing

space now, which was utilised by having something to eat and drink.

On inquiries being made for Yunacka no intelligence of him could be

got, except that he had been last seen in the tree, firing away as if his

life depended on expending all the ammunition in his pouch. The garrison

was in capital spirits, for they had had the best of the fight so far,

but the enemy would be sure to return to the attack, most likely at night.

Sentries were posted and relieved regularly, a guard having been told off,

commanded by one of the Europeans as officer, to see that the necessary

precautions against surprise were properly carried out. The darkness would

prove more dangerous than anything else, as then a determined enemy could

escalade the entrenchments, and carry the place with a rush. Val was in

high spirits; he had knocked over a lot of sepoys, as he averred, and was

anxious for the fight to recommence.

“Dana is very anxious about Yunacka,” he observed. “I hope the fellow

hasn’t got into trouble.”

“Trust him for that,” replied Harry. “He is like a monkey, and would

be out of reach of their muskets before he could be touched.”

While speaking Yunacka appeared, bringing with him a set of belts, pouch,

etc., and a sepoy’s musket, which he had evidently stripped from a dead

sepoy.

Harry was delighted to see the wild boy again, and patted his head approvingly.

An idea struck him. If Fitzmaurice permitted, he would head a sortie, and

bring in arms and ammunition, the former of which were needed, as many

of the natives were armed only with muskets of the old pattern, some of

them having flint-locks.

He at once sought the father of Dana, who agreed to Harry’s proposition,

stipulating, however, that they were to avoid a collision with the enemy

if possible.

Val was to accompany him, as was also Yunacka. They were in capital

spirits, and hoped to return with a lot of prizes.

CHAPTER XVIII

“Good-bye, Harry,” said Dana, “Mind and take care of yourself for all

our sakes; and you too, Val. Look after Yunacka, or he’ll be getting you

all into some terrible scrape.”

They promised, and started, creeping out of the gate on their hands

and knees. Not a word above a whisper was to be exchanged, or a shot fired,

unless absolutely necessary. Harry went forward, stooping low, with his

rifle at the trail. He was careful to secrete himself behind bushes and

shrubs, until he could run across a clear space with safety. No one was

in sight, but he heard the hum of voices some distance ahead, and saw the

watch fires of the enemy.

He was about to return, when he perceived a native creeping stealthily

towards the entrenchments. Harry could have shot the fellow with ease,

but was afraid of alarming his comrades. He decided to follow in his wake.

Resting his rifle against a tree, he drew his hunting knife, and stalked

after him. He watched the man’s every movement, stopped when he did, and

then, advanced, gaining on him by swift strides. Suddenly Harry espied

a large tiger crouching ready for the spring. Harry threw himself flat

on the ground, but in doing so made a noise, which attracted the native’s

attention. The movement was fatal to the startled native. With a roar and

a bound the tiger was upon him, bearing him to the ground.

Harry shuddered, and turned to retrace his steps, but suddenly halted

when he overheard voices. He pulled up only just in time. Another minute,

and he would have rushed right into the arms of the enemy. There was a

screen of bamboos between Harry and the rebels. “Let the attack be made

to-night,” said one.

“No; wait till the others come up,” was the reply.

“Berga has gone reconnoitring. When he returns we shall know where to

direct the assault. Baboo says they cannot hold out-long. There’s plenty

of money and jewels for us inside the house, and a beautiful girl also.”

Harry clutched his hunting-knife fiercely, and sprang towards the speaker.

But at the same instant the roar of the tiger awoke the echoes, and the

men turned and dashed into the thicket. Harry reached the tree where he

had left his rifle; and was soon with his companions, who had become alarmed

at his lengthened absence. The task of stripping the dead of their accoutrements

was soon accomplished. Twelve dead bodies attested the deadly accuracy

of the rifles. Harry gleaned from the number of the regiment on the waist-belts

that the mutineers belonged to his uncle’s corps, in which was also Val’s

father.

He called his friend’s attention to the fact, and the thoughts of both

went out instantly to the loved ones. Were they safe, or had these scoundrels

imbrued their hands in their blood? They felt sick at heart when they imagined

what might have happened. They returned to the garrison, which had been

kept under arms to rush to their assistance, had the occasion arisen. A

dozen stand of arms, and scores of rounds of ammunition, were not to be

despised. Dana complimented Harry on the success of the enterprise, much

to Val’s annoyance.

“Val did as much as I,” he remarked. “We share the praise between us,

don’t we, Val? But we’ve made a discovery that has saddened us, Dana.”

“May I ask in what way?”

“The mutineers belong to Val’s father and my uncle’s regiment. We do

not know the fate of our relatives.”

“Let us hope for the best. Don’t forget that a Providence watches over

all, and nothing can happen unless permitted for some wise purpose.”

Harry took the earliest opportunity of drawing Mr. Fitzmaurice aside,

and communicated to him what he had seen and heard.

“I am but an inexperienced youth,” he observed, “but it appears to me

that it would be wiser far to attack before they were reinforced, than

to wait for them to receive reinforcements. They have adopted no precautions

against surprise.”

“It is not a bad idea,” observed the gentleman, “but we are so few in

number that the loss of even one would be irreparable.”

“I am sure our loss would be nil. We could fire from ambuscade. Think

of the wholesome lesson it would teach the wretches. They might retire

altogether.”

“We will call a council of war, and decide the matter,” he said. “I

must confess I am in favour of the idea. Nothing venture, nothing win.”

“Besides, sir, personally I owe the fellows a grudge. They belong to

my uncle’s corps.”

“We are in the hands of Heaven, my dear boy. We cannot do better than

trust in Providence.”

It was finally decided to surprise the enemy’s camp that night at all

risks. Of course it would be impossible that Dana should take a part in

such a hazardous undertaking, although she begged hard to be permitted.

She was to remain behind in charge of a small garrison, and received instructions

in case of defeat, or the destruction of the force, to make her way to

the nearest European station, which was Delhi.

“Dana,” said her father, with solemn impressiveness, “it may be my last

wish; I know you will obey me. Here is a sealed packet; in case I fall,

open it; it will tell you all.”

“I know you will return,” she exclaimed, kissing him; “but in any case,

I will prove myself worthy of you.”

Harry’s heart was full as he beheld this simple, but affecting scene,

which told of the deep love they felt for each other. Several times Harry

caught his eyes fixed on his with a yearning look, for which the youth

could not account.

“Why should he regard him so?”

It was a problem which the future alone could solve.

CHAPTER XIX

The surprise party sallied forth silently, like spectres, into the

darkness, leaving Yunacka behind, as was supposed. Everything depended

on secrecy and despatch, and they had taken every precaution against detection.

The natives wore no shoes, and the Europeans placed stockings over their

boots to deaden their tread. They had plenty of ammunition, and better

still, brave hearts, which were not to be easily daunted.

So far as could be judged, the natives, to a man, were loyally disposed,

but religious and national prejudices might operate in their minds, at

any moment, against the Europeans. However, they had staked all on the

hazard of a die, and must abide by the consequences. Silently they moved

forward, the Europeans in front, the natives in rear, in charge of Golob,

the shikaree. He was a noble fellow, and one to be trusted with all that

one held nearest and dearest in life.

Harry walked a little in advance of the party, with acute hearing and

watchful eye, ready to whisper “halt” if danger threatened. Presently the

glare of the watch-fires told that they were near the goal, and must prepare

for a desperate struggle. Harry was deputed to reconnoitre the position.

Leaving his rifle with Val, he crawled forward, drawing his body along

the hard ground like a serpent. A couple of sepoys were sitting before

a fire smoking, their muskets resting against their right shoulders. They

were half asleep, owing to the effects of the tobacco, which contained

a quantity of opium.

“They are delivered into our hands,” thought Harry, with savage glee.

He took note of the position of the cannon, and saw no gleaming port-tire

ready to hurl death from its frowning muzzle. The arms were piled, which

was in itself a fortunate circumstance, as by a rush they might be captured.

The soldiers were lying about in small groups of twos and threes, sleeping

soundly. Nothing could have been better for the purpose. Harry was on the

point of returning, when one of the sepoys roused himself and yawned. Standing

upright, he looked around, and fixed his eyes in the direction of the crouching

youth.

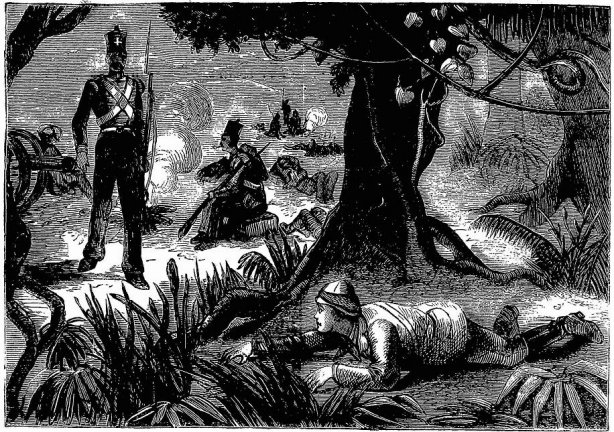

Standing upright, the Sepoy fixed his eyes in the

direction of the crouching youth.

After a series of yawns the sentries settled down into a drowsy state

again, and the youth crawled back to his companions. Swiftly but silently

the surprise party moved forward, each grasping his weapon firmly. Harry

pointed out the various positions of the camp to Fitzmaurice and Clarence,

especially that where the field-piece stood. They then stationed themselves

so as to pour in a fire from every direction upon the sepoys. Fitzmaurice

fired the first shot, which was instantly followed by a general volley,

continued by independent file firing. Clarence and Harry made a dash at

the six-pounder, bayoneting two of the gunners.

“Quick, Clarence!” cried Harry, “the spike!”

Clarence placed the spike in the vent, and held it there, while Harry

struck it with his rifle. The fight went on with but little show of resistance

on the part of the mutineers, who were shot down or bayoneted before they

could seize their arms. Some of the attacking party were wounded, but none

killed, and all fought bravely on. The din was increased by the roar of

wild beasts, the trumpeting of a couple of tame elephants and the roars

of camels.

Flash upon flash lit up the darkness. The battle was soon over, the

surprise complete, and many of the enemy lay with upturned faces, some

writhing in agony, others past all earthly troubles, while many escaped

in the darkness. The victors gathered all the arms and ammunition and took

them to the garrison, also the field-piece.

The wounded men of the party were conveyed on rude litters to the house,

and they determined to return for the enemy’s wounded in due course. They

were on the point of starting, when there came a yell as if from some human

being in agony. It was repeated, accompanied by mocking laughter. The moon

rose at this juncture, flooding bush and greensward with a soft, brilliant

light.

The yells and laughter were continued, and in a few minutes were followed

by some one dropping from the branches of a tree. Another figure came after

him, and both made in the direction of the party. They were a mutineer

and Yunacka, the latter in full chase, armed with a naked bayonet, with

which he prodded his victim from time to time. The wild boy seemed to have

imbibed a thirst for blood. Nor had he any fear of death himself. He would

have rushed into a breach or faced a battery.

They made the unfortunate wretch a prisoner, thus saving him from the

fury of Yunacka. The party had hardly got back to their entrenchments than

the sound of a bugle awoke the echoes of the jungle. The call sounded was

the “advance,” but they were at a loss to know whether it was given by

friends or foes.

It was just possible their position might have been made known to the

nearest European garrison by one of their spies, and that a detachment

of troops had been sent to their aid. All this was mere conjecture. The

bugle sounded again. This time the “assembly,” and the echoes went rolling

along the leafy alleys.

CHAPTER XX

The wounded were conveyed to a room which had been set apart as a hospital.

It was comfortable though small, and contained a few beds for the accommodation

of such patients as might be brought there. Fitzmaurice and Clarence were

about the only two that understood anything about surgery. Luckily the

wounds received were not dangerous, and were easily dealt with. Dana was

ready with a supply of bandages, lint, etc. The Europeans were glad to

see such an excellent spirit pervading the native portion of the garrison.

Without their aid they could not hope to cope with the odds arrayed against

them.

Any disaffection would prove their ruin, and bring death to all, and

dishonour upon Dana.

“Well, Harry,” she said, “your expedition has proved a great success,

I fancy they won’t attack us again in a hurry.”

“Not that party, Dana. But unluckily they expect reinforcements, I heard

them say so.”

“We have plenty of ammunition now, Harry, and another cannon. But where’s

Yunacka?”

“He returned with us, and has since gone out again, I suppose.”

“Harry,” she said seriously, “do you know I have a dread that Yunacka

will seriously imperil our safety?”

“You do not suspect him of treachery?”

“No; but if the siege goes on the enemy will see how he gets in and

out of our position, and copy his example.”

“I never thought of that. There’s danger from that source, Dana. But

I’ll try and hit on a plan for stopping his migrations. He’s as active

as a squirrel.”

Clarence came out of the hospital and joined them, saying —“Harry, come

and help me to get the spike out of the gun. If it isn’t loaded, I think

we shall be able to manage it.”

“There’s that bugle again,” said Dana. “What is it sounding now, I wonder?”

“The ’advance,’” replied Harry. “I’m sure the mutineers have been reinforced.

We must be on the alert. I’ll just run round and see that all our sentries

are at their posts. We mustn’t be caught napping.”

Harry set off to see that a good watch was kept, when Golob came up

to him and said —“Harry sahib, plenty fighting soon. More sepoy. Got big

guns.”

“How do you know that, Golob?”

“Put ear to the ground, and listen. Do it plenty time in jungle, when

hunting.”

The youth’s worst suspicious were confirmed. He sought out Clarence,

and told him of what Golob had said.

“It can’t he helped, old fellow,” he replied, nonchalantly, “Let us

hope for the best. Give us a help here, Harry. If we can get the spike

out, we’ll give them a dose of their own grape and canister.”

They were glad to find that the field-piece was not loaded, which enabled

them to work the sponge staff about freely in the region of the breech

of the gun, with a view of dislodging the spike. For a time all their efforts

were unavailing, although they manipulated the staff skilfully.

“I’m afraid the head of the staff has too much play, Clarence.”

“That is the fault, no doubt, Harry. Perhaps if we wrap something round

the head of the staff, we’ll succeed,”

The spike became dislodged at length. The six-pounder was now ready

for use. Fitzmaurice and Val congratulated them on the success of their

labours.

“I told our commander of what Golob had said,” remarked Harry, adding

— “I think he is perfectly correct. But it would be as well if we ascertained

the truth for ourselves. Golob and I could do this.”

“I don’t want you to be running your head into danger always,” said

Fitzmaurice.

“Give some one else a chance, Harry,” said Val somewhat spitefully.

He was jealous of the lead Harry was taking.

“I don’t want to put myself forward,” said Harry. “I don’t mind casting

lots with you to see who’s to go out on this business.”

“Why, of course, that’s the fairest way, Harry,” said Val. “Heads or

tails, that’s fairest.”

Golob, Mr. Fitzmaurice and Clarence looked gravely on while Val and

Harry were tossing like two street Arabs to see who was to face death and

danger. Harry won.

“Never mind, old fellow,” he remarked in a whisper, “you have the best

of the position.’’

“How do you make that out?” said Val snappishly, “Do you think I’m afraid

of danger, Harry?”

“No, Val, you’re a braver lad than I by far. What I mean is, you have

the privilege of being near Dana, and to guard her against danger. You

mustn’t forget that, Val.”

Val was easily pacified and wished his friend “God speed” and a safe

return. As Golob was an experienced hunter, and knew how to track wild

beasts to their lairs, Harry placed himself under his guidance. It was

a ticklish adventure he was bound on, especially as there were plenty of

mutineers about.

Golob and the youth issued stealthily from their entrenchment, armed

only with revolvers and hunting-knives, but with brave hearts that knew

no fear.

CHAPTER XXI

They stole noiselessly towards the site of the enemy’s encampment,

where such a glorious surprise had recently been effected. They found only

the dead — not a living creature was near the place. Evidently the mutineers

intended giving the spot a wide berth, not caring for a repetition of past

disasters. And yet no position could they have selected better suited for

an encampment if only ordinary precautions had been taken.

“Where do you think they are, Golob?” said Harry.

Bending his ear to the ground, Golob listened, and then pointed in the

direction taken by the enemy. They stole forward cautiously, knowing that

on all sides danger lurked. “Hist!” cried Golob suddenly, in Hindostanee,

holding up his hand. “Down — hide; somebody is coming!”

Crouching behind the bushes, Harry and the hunter held their breath

in suspense. The mutineers were posting sentries far in advance of their

camp. They overheard the instructions given to one of the sentinels.

“Golob, he must die,” whispered Harry.

“Yes; the knife is best.”

“Let me do the work,” said Harry.

“No, you are but a boy, I am a man, Golob does it.”

Finding it useless to try and move him, Harry agreed to the arrangement.

Like a tiger crouching for a spring, or a boa-constrictor lying in wait

for its prey, Golob fixed his eyes on his intended victim, and watched

his every movement, the while gliding nearer and nearer to him. As if the

sentry had a sense of the presence of unknown danger, he looked about him,

and halted at the slightest sound. Gathering himself together for a final

effort, the shikaree suddenly launched himself at the sentry, like an arrow

from a bow. There was a sharp, short struggle, and the fellow fell dead

without a groan, the hunter’s knife buried in his heart, Harry caught sight

of the expression on the man’s face as the blow was struck, and with a

shudder turned away.

Suddenly he found himself seized, and, although he struggled desperately,

was thrown to the earth and made a prisoner. Finding resistance useless,

he kept perfectly quiet, and allowed himself to be carried to the enemy’s

camp.

“We found this boy,” said one of his captors, “and brought him here,

major, thinking he might give you some information.”

“Why, it is Harry Coverdale,” said the major, “who was an officer in

his uncle’s corps.”

“Yes,” replied Harry, “it is I, but I never expected to find you a rebel,

Custonjee; where is my uncle?”

“Heaven only knows,” he replied, with a shrug of his shoulders. “Dead,

I hope, as I trust all Europeans will be soon; we want India for ourselves.”

Indignation kept the boy silent, and he glared at the dark scowling

faces bent upon him on all sides. He recognised many of the men, with whom

he had been on very friendly terms in the happy past, when murder and rapine

did not stalk openly through the land. Strangely enough he felt no fear

of these living men, fiends though they had proved themselves,

“Harry,” said the major, “we have been friends, and I would save you.

Your life is in your own hands. Consent to join us, and we’ll make you

an officer.”

“Custonjee, you say you are my friend: do not insult me. I’d die a thousand

deaths rather than desert my queen and country.”

He spoke in Hindostanee, so that all who stood around could understand

him. Join such miscreants! Men whose hands perhaps had been imbrued in

the blood of those nearest and dearest to him! His words evoked murmurs

of anger from the mutineers, and the youth expected either to be instantly

shot or stabbed for his boldness.

“Your garrison can’t hold out,” said the major, as he smoked complacently,

seated cross-legged like a tailor. “We know how many there are there, and

all about them; when we take the place —”

“When you do,” remarked Harry sneeringly.

“We shall blow the natives from guns, and hang the Europeans, excepting

the girl, who is far too pretty to die. She shall be my wife. Ha! ha!”

“You old villain!” cried the youth. “Were I not powerless I would kill

you. Bah! you and your men are cowards and murderers!”

In reply Harry received a violent blow on the head, and fell back stunned.

CHAPTER XXII

When Harry recovered consciousness, he learned that he owed his life

to the interposition of the major, who had threatened anybody with death

who molested him further.

“He was always an outspoken youth,” he remarked, “and I like him all

the better for his courage. I have no son, and therefore I’ll adopt him

as my own.”

This was received in a bad spirit by the mutineers, whose lust for blood

was insatiable. But the major was firm, and Harry was permitted to live.

The major gave him a bed near him by the fire, and made his attendant bring

him meat and drink, of which he partook. The old man’s kindness won upon

his heart.

“Keep quiet,” said the major in a whisper. “I’ve adopted you as my son

openly; trust in me and all will be well.”

“Can you give me any news from home, Custonjee? Did they perish? And

the Aubreys — are they safe?” asked Harry.

“Yes; one and all. Do you think I would have stood by and seen my friends

butchered? No, Harry, I’m not so bad as that. I and a few comrades escorted

them as near as we dared to the English camp at Delhi.”

“You are good and kind,” replied the youth, pressing his hand, and falling

asleep.

He awoke refreshed.

“Don’t mind my manner to you at times,” whispered the major, “I must

speak roughly, perhaps threateningly, to keep up appearances.”

“I understand, and will submit to anything but right down insult or

indignity,” replied Harry.

The mutineers numbered quite two hundred and fifty men, including cavalry,

infantry, and artillery, all arms of the service being represented. Three

field-pieces stood grim and silent, only waiting to be wakened into life

by the sulphurous compound known as gunpowder. The sowars, or irregular

cavalry men, numbered some thirty, and were rollicking-looking fellows,

ready to commit a murder, drink a stoup of liquor, or kiss a pretty girl.

“What would I not give to warn my friends,” thought Harry.

The odds were great against his party, and unless they kept constantly

on the alert, the enemy would be likely to surprise them. In any case they

would be sadly harassed by false alarms and feints of attack. Another danger

against the garrison was the fact of such a man as Custonjee being in command

of the mutineers. He was known as a clever officer, and had seen a good

deal of active service, which after all is the best qualification in a

commander, who is thus enabled to combine theory with practical experience.

They were well provided with intrenching and mining tools, which could

be turned to mischievous account. The camp was astir betimes, and from

the preparations going on Harry concluded that the garrison was to be attacked

that very morning. Custonjee advised him to remain in camp, without attempting

to escape, if he did not wish to be shot by the sentries. Harry rebuked

the major in no measured terms for heading an attack on his friends.

“Always impetuous,” he said in reply. “Wait. I have a part to play.”

“I love my friends, and hate your men. Let me go and help the garrison.

I cannot stay here listening to the thunder of cannon and the rattle of

musketry without panting to be in the fight.”

“Be sensible,” he replied. “You’ll never make a clever man, if you do

not learn to control your feelings now.”

The sepoys grinned, loaded their muskets with ball cartridges, and made

all kinds of jokes at the expense of those they were about to attack. They

even alluded to Dana, at which the youth’s blood boiled, and he looked

round wildly for some means of escape. Every avenue was barred by glistening

bayonets, and his heart sank within him.

CHAPTER XXIII

Listening to catch the sound of firing, Harry heard a rustling in the

tree under which he stood. Raising his eyes he gave a start of delight.

Yunacka sat in the branches grinning and shaking his fist at the nearest

sentinel with such grotesque pantomimic action that Harry fairly burst

out laughing.

“What are you laughing at, Harry sahib?” he asked. “Ah! a monkey, big

fellow too. Shall I shoot him for you?”

“No, no, let him be. Ah! the fight has commenced. Listen!”

Heavy firing was heard, and then came answering sounds from the garrison,

the sharp, peculiar crack of rifles, as distinguished from the ping of

the musket.

“Ah!” exclaimed the youth, “that’s Golob’s rifle; I know the sound,

it barks like a dog. Some one has bit the dust, and there’s a volley from

the housetop. Bravo! bravo!”

His excitement was so great that he forgot everything save the noise

of the battle. The cannon came into play, thundering forth notes of defiance

which remained unanswered for a time. Then came the bark of the six-pounder,

which belched forth shot and shell. It was evident that the defenders had

managed to get the small field-piece on to the roof of the house.

“Glorious, excellent!” cried Harry.

Yunacka dropped from the tree to Harry’s side, and it occurred to the

youth that the wild boy might be able to convey a note to his friends in

the garrison, apprise them of his safety, and that of his own and Val’s

relatives. Leaning back against a tree, he drew forth a pocket-book and

pencil, and began to write, looking up frequently to see whether his actions

aroused suspicion. Luckily the sepoys paid little attention to what he

was doing. Having finished the note and directed it to Mr. Fitzmaurice,

Harry waited for an opportunity to make Yunacka understand that he wanted

it conveyed to the jungle home. The wounded began to come in fast, evidencing

the accurate fire of the garrison. One of the wounded men became so infuriated

that he picked up a musket and fired at the boy, luckily without effect.

So great was the rage of the wounded that the sentries left in charge of

the young captive thought it right to tie him to a tree out of sight of

their comrades. This gave Harry the opportunity he desired of speaking

with the wild boy.

“Yunacka,” he said, in Hindostanee, loud enough only for him to hear,

“take this to Dana. Do you understand me?”

The boy looked puzzled for a moment, and then his face cleared. Taking

the note from Harry’s hand, he peeped round the tree, and then went off

on all fours like a monkey. It suddenly occurred to Harry that he might

work himself free from his bonds, and escape from the rebel camp unseen.

“Thank Heaven, our fellows are well under cover,” thought Harry, “otherwise

there’d be very little chance for them. I hope no one is hurt. Perhaps

I may be with them myself soon. At all events, here goes to try.”

The ropes were not tight, so he had no great difficulty in freeing himself.

But before casting off his bonds altogether, he waited to see whether anybody

would visit him, as he did not expect to be left entirely without supervision,

especially as the major had given strict orders to guard him closely. It

was as well he took this precaution, for one of the sentries came suddenly

upon him.

“I think it will be safe to release you now,” he remarked; “but mind

what you are about. Our fellows are as savage as bears at the peppering

they’ve received.”

“Serve them right,” said Harry. “I won’t be released. You thought fit

to place me here, and here I’ll remain until Custonjee returns.”

The fellow was proceeding to release him, when, dropping the cords,

and snatching a pistol from his breast, Harry shot him through the head,

and ran into the jungle. Several shots were fired after him without effect.

Exhausted at last, he threw himself under the shade of a mango-tree. The

coolness of the spot, and the quiet, after the excitement, soothed him,

and he fell into a deep slumber. He awoke with a start, and was surprised

to find that it was evening, and that the sun would soon be below the horizon.

He listened for the sounds of firing, but heard none. A cold sweat bedewed

his forehead, a terrible feeling seized upon his heart, and he dashed forward

at the top of his speed.

CHAPTER XXIV

Then Golob returned without Harry, and told how strangely he had disappeared,

grief and consternation was universal at the lad’s supposed untimely fate.

Of course Golob was unable to give Fitzmaurice any information concerning

the strength or intentions of the mutineers, as the untoward accident prevented

his getting near the camp. Val was for making a sortie to ascertain Harry’s

fate, and in this he was backed up by Dana.

“It would be dishonourable to leave him to his fate, if alive, or let

him remain unavenged, if dead,” she remarked. “Poor, dear Harry, I began

to love him as a brother, he was so kind to me and so full of fun.”

“I know you liked him very much, Dana,” said Val, in a voice of emotion,

“and I was jealous; but you may marry him as soon as you like, if he comes

back, I won’t object.”

Dana could not help smiling at Val’s impetuous generosity in disposing

of her hand in marriage.

“I’ll bear your permission in mind, Val,” she said, with just a tinge

of good-natured satire in her tone. “I’d do anything to bring the poor

fellow back again.”

“It’s very good of you both to feel so anxious about the safety of our

brave young friend; if we had a large force at our disposal, I’d gladly

head a sortie to rescue him, dead or alive; but, as you know, we are sadly

outnumbered, and every man’s life is of the greatest consequence to us

all.”

So spake Fitzmaurice in a grave voice. His face was anxious and haggard.

This solicitude may have arisen from the fact of his having given a hasty

and inconsiderate sanction to Harry’s undertaking a mission so fraught

with danger. Next morning, at break of day, the garrison was up and at

work strengthening the defences, and preparing for the attack, which was

fully expected. After a consultation with Clarence and Golob, Fitzmaurice

determined to mount the six-pounder on the roof of the house, and to call

the house the “Sandbag Battery.” This took some time and exercised the

ingenuity of the garrison to a considerable extent, but necessity is the

mother of invention and aided the labour to a successful issue.

Once up, the battery was soon finished and ready for action. Arms were

cleaned and looked to; pistols and revolvers loaded, and placed in readiness;

and then the bell summoned all to breakfast. Loopholes were made in stockades,

to enable marksmen to pick off the enemy, and nothing that skill could

devise was left undone. The commandant moved from post to post, speaking

words of commendation to the natives, who loved him as a kind, considerate

master, and felt that for such as he they could willingly die. The menagerie

was still intact, Dana having pleaded for her pets, not caring that they

should be turned adrift or destroyed.

The greatest drawback the garrison had to contend with was in the only

well of water being in an exposed position; although the supply was in

no danger of being cut off at first, yet, should the outposts be captured,

water could then only be obtained at great risk to life. The surplus ammunition

was put in wooden boxes, and buried near the house. Whilst these preparations

were in progress Yunacka was looking about everywhere for Harry. Knowing

that Golob had accompanied Harry, Yunacka followed him about; but not being

able to speak, could not put any questions to him. With more intelligence

than any one credited him with, he brought some clothes of Harry’s, also

his rifle, etc., and showed them to Golob, and then by signs made him understand

that he wished him to speak about his absent friend. This led to the wild

boy finding Harry eventually.

Custonjee led his men against the garrison. The force under his command

consisted of two guns (nine-pounders), infantry, cavalry, and sappers.

He was an able commander, and did nothing rashly, or in a hurry; nor did

he in this case, although his force greatly outnumbered that opposed to

him. He reconnoitred the defences, and saw that they were stronger than

he was led to believe.

“Look at the parapet of that house,” he said to his lieutenant, handing

him a pair of field-glasses, “and tell me what you think of those sandbags.”

“It means a battery, major. Ah! I have it; it’s the six-pounder they

captured from us. We’ll have to be cautious how we expose our men to its

fire.”

“Is there no other position which our guns could take up?” Custonjee

asked.

“None; the place is surrounded by stockades and natural barriers, which

quite shut it in. I wish that screen of bamboos was down, major.”

“So do I. Can’t we set it on fire?”

“Not easily: the wood is too green to burn."

“To-night we must entrench ourselves at this spot. No supplies must

reach them. We shall also mine their stockades, and harass them in every

way. Nothing must be left undone to reduce the place.”

“What is to be the fate of the garrison if the place falls into our

hands, major?”

“Time enough to talk of that when it does. Give me a back, Lutchman;

I mean to get up this tree and reconnoitre. I have an idea our sharpshooters

would prove useful up there.”

The lieutenant, a slim man, not half the size or weight of the major,

heard this request, which amounted to a command, with dismay.

“Did you say you wished me, or one of the men, to give you a mount,

sir?” Lutchman asked, as he gazed upon the awful proportions of his chief.

“You!”

“But I can climb like a squirrel,” said the lieutenant.

“Indeed; well, you can follow me. But let me tell you, I think you’ll

be exposed to a sharp fire from the rifles on the housetop. Come, Lutchman,

are you ready?”

He was ready, but not at all willing; nor was he to blame for thinking

the service exacted from him a weighty one.

Stooping, he allowed Custonjee to mount on his back, supporting himself

the while against the trunk of the tree.

A titter ran through the ranks at sight of the inequality of the officers,

as regards weight, and at the ridiculous way in which Lutchman bent under

his superior, who balanced himself like a dancing bear.

Despite his corpulency, however, he managed to get into the tree and

climbed to a respectable height, where he squatted in the fork, and looked

through his glasses.

“Waugh!” he cried, from his lofty post. “Wonderful They’ve made the

place very strong.”

Fitzmaurice, who was sweeping the open space with his field-glasses,

caught sight of something white in the tree.

“What do you make of that white object?” he asked, as he handed the

glasses to Clarence.

“It’s a human being; but whether a friend or foe I can’t determine.

Suppose I try the effect of a shot, sir?”

“For Heaven’s sake don’t!” said Val, grasping Clarence by the arm; “it

may be Harry.”

“Val is right,” said Dana; “it’s better to spare an enemy than destroy

a friend.”

These remarks had the effect of sparing Custonjee, who must have fallen

under the unerring rifles of Clarence and his comrades.

“Shall I come up, major?” asked Lutchman.

“No; I’ve got to come down, though, and how to do it I don’t know. If

I’m not sharp they’ll be firing at me.”

The lieutenant enjoyed his superior’s predicament, and chuckled inwardly

over it, but answered —“I don’t know how you will get down unless we borrow

a ladder from the garrison.”

“I’ll be down presently,” thought the old man, as he attempted to descend.

And so he was, for, losing his footing, the fat old man fell atop of

his lieutenant, and together they rolled over and over upon the ground.

CHAPTER XXV

The fight now commenced in real earnest, the first shot being fired

by the rebels, who threw out skirmishers, and took advantage of every bit

of cover, thereby showing that they were well-trained soldiers, as indeed

they were. The six-pounder belched forth flame and destruction, and the

rifles and muskets kept up a regular “devil’s tattoo,” making the place

ring again. Men shouted stern commands which could be heard above the din

of battle. Bugles sounded, and then came the sonorous “bang, bang” of the

enemy’s cannon, followed by the sharp terrier-like bark of the little field-piece

on the roof. Custonjee kept his men well in hand, and exposed them as little

as possible. Fitzmaurice on the housetop kept a look-out on the movements

of the enemy, resolved to check any sudden rush on their part, which was

more than probable they would try to make.

“Golob,” he said, “take half-a-dozen fellows, the best shots you can

select, and plant them in the bamboo thicket. They will be under your command.”

The fine old fellow saluted, and in less than five minutes the place

was occupied in obedience to orders. Hardly had this movement been executed

than a score of sepoys advanced at the double to occupy the thicket. If

Custonjee had only thought of this in time, the garrison could not have

prevented him from securing that position.

“Now, men,” said Golob sternly, “fire! Be steady, and take good aim.”

From the thicket and housetop a deadly fire was opened upon the advancing

mutineers, which checked them effectually, with the loss of several killed.

Having forced the survivors to retire, Golob and his party turned their

attention to the enemy’s artillery, upon which they opened a galling fire.

Custonjee bit his lip with vexation, and resolved to drive these waspish

musketeers from their fastness. His men began to dread serving the guns,

so deadly was the fire of Golob and his companions, his own more especially,

as every time his rifle sent forth a bullet a man fell.

“The first man who flinches from his duty,” said Custonjee sternly,

“will, be shot. Drag the guns closer and search the thicket with grape.”

Knowing from experience how stern a disciplinarian he was, they did

not care to disobey him, although obedience meant certain death for some

of their number. Custonjee attended the guns himself, and was so cool under

fire that his men could not, for very shame’s sake, do aught else than

follow his example. He laid the first gun himself, and fired it, sending

a volley of grape scattering like hail through the thicket. Golob had told

his men to lie down, and to keep close, until the gun had been fired, when

they were to commence afresh their work of death in picking off the gunnery.

Such, however, was Custonjee’s determination that he would not give up

the undertaking, although several of his men were killed, and many more

wounded, he himself slightly.

Fitzmaurice perceiving the danger to Golob and his party from the searching

artillery fire they were being subjected to, signalled him to retire within

the garrison; which he effected with the loss of one man only, whose body

was brought in for burial. This was the first actual death of any of the

defenders, and the circumstance had, naturally, a depressing effect. Meanwhile,

Custohjee, unaware of the retreat of the sharpshooters from the thicket,

continued to fight his guns, and he was in the act of laying-one, with

bare head (it was very bald), his turban having fallen off, when he got

a crack on the pate with a wood-apple, which set him dancing with pain.

The gunners came in for their share of these missiles, which are not

only large, but when unripe as hard as iron. The worst of it was, no one

could be seen up in the tree to account for the shower which drove the

fellows from their guns, a feat which Golob and his men had failed to accomplish

with their trusty weapons.

“There he is,” said one of the men, at last, on catching sight of a

black hairy object up the tree; “it must be the evil one himself.”

No sooner had he given his opinion than he received a blow on the forehead

from an apple which floored him. This event was followed by peals of unearthly-

laughter, which so terrified the mutineers that, seized with a sudden panic,

they bolted, leaving the old major to waddle to a safer spot as best he

might. The cause of this fright was Yunacka, who was making his way back

to the garrison. He was up the tree waiting for an opportunity to get inside

the house, when Custonjee and his party came up with their guns, and halted

under the tree. Terrified at first by the sound of the firing, he did not

become aggressive, but taking courage at last, he began operations by nearly

breaking the old major’s head. If the garrison had only known the guns

were deserted they could have made a sortie, and spiked the cannon, but

unfortunately they were not aware of what had taken place. Yunacka, seeing

the coast clear, descended, and proceeded to examine the gun with great

curiosity, and to play with the port-fires. which were burning slowly in

their respective buckets.

“There he is again,” shouted one of the sepoys, pointing to the wild

boy, who had taken up a port-fire, which he held close to his face, and

which gave to it a demoniacal appearance.

“Fire at the thing,” said Custonjee; “it’s only a monkey. Shoot it.

It nearly broke my skull.”

Luckily for Yunacka, the men who did fire were so convinced of the uselessness

of attempting to shoot a fiend, that they took no aim, and therefore the

wild boy escaped. Seeing him amusing himself with the portfires, a party

of monkeys came trooping down, and joined him. They scampered over the

guns and tumbrils, prying into all kinds of mysteries, and tasting some

loose powder, which, not being to their liking, they spat out, with sundry

grimaces and expressions of disgust. Yunacka ran about with the lighted

fire, touching up first one monkey and then another with it, enjoying their

screams, as they scampered out of the way. Several of the larger ones,

however, made a set upon him. and to escape he jumped upon the powder waggon,

port-fire in hand. Several sparks from it burnt his body so that he threw

it away with disgust, and it fell right into the waggon among the powder.

He leapt from the waggon and climbed a tree, chased by the monkeys.

Alarmed for the safety of the guns, Custonjee ordered the artillerymen

to withdraw them to safe distance. They advanced to obey the order, when

there was a terrific explosion, the waggon and its contents were hurled

into the air, together with a crowd of poor inoffensive monkeys, while

the débris wounded several of the advancing mutineers. Fitzmaurice

and his companions thought at first it was an attempt to blow up a portion

of the outworks. Therefore he and the others hastened down to reinforce

their comrades in the trenches so as to drive back the invaders, or to

die gallantly in the attempt. Yunacka, on hearing the explosion, tumbled

headlong off the highest branch of a gigantic tree, and would have been

killed by the fall, if he had not saved himself just in time by catching

at a lower bough, to which he clung. Thinking the rebels were the cause

of his fright, he became furious with passion. Descending, he seized a

broken branch and attacked them savagely, uttering loud cries of rage,

as he struck out freely, right and left. His fiendish appearance, the contortions

of his visage, and the glowing expression of his small eyes, which resembled

orbs of fire, so terrified the men that they fled, leaving him again master

of the field, which he quickly evacuated, and reached his friends in safety.

It need hardly be stated how pleased every one was to hear of Harry’s safety

so far.

“Val,” said Dana, in a whisper, after hearing the good news.

“Yes, Dana.”

“Harry, must be rescued.’’

“He must, and shall, even if I perish in the attempt. To me he is more

than a brother.”

“Keep this resolve to yourself, Val. You and I’ll slip out to-night

to look for him, that is if we are lucky enough to escape with our lives

from the attack, which the enemy now seem inclined to make again.”

She was correct, for Custonjee resolved to try conclusions with the

defenders, and pushed forward his men again, getting them close to the

stockade, while a fatigue party brought up escalading ladders. The reserve

ammunition for the nine-pounders had also been brought up to the front,

and he was in a position to again commence the assault. There was a regular

artillery duel between the enemy’s field-pieces and the solitary six-pounder,

which latter did good service.

This, however, was only a ruse on the part of Custonjee, to mask his

real intention of gaining the place by escalade, and to give him time to

carry out his plans, which, to do him justice, were well conceived. The

parapet of the house was a good deal knocked about and the sand bags displaced,

but, luckily, no one was hurt, although the plucky defenders had several

narrow escapes. Golob, who was visiting the sentries, had his attention

called by one of them to a party of mutineers, carrying ladders. Golob

ran back to Fitzmaurice, and told him of the circumstance.

“This must be seen to, Golob,” he remarked. “’Tis evident they mean

business this time. We must leave the housetop now, and defend our position

from below, Heaven grant us success.”

Every post was strengthened, and the picquets had orders to retire on

the entrenchments, firing as they retreated, if the mutineers succeeded

in forcing the outer defences. Each man had an extra supply of ammunition

served out to him, and was further exhorted to make a desperate resistance,

inasmuch as defeat meant torture or death.

CHAPTER XXVI

Exactly at one o’clock the picquets commenced to be driven in by the

enemy who had gained the outer defences by escalade.

“Steady, men,” said Fitzmaurice in Hindostanee. “Remember you fight

under cover; take aim, and don’t forget to use the bayonet when the proper

time arrives.”

Before leaving the housetop, Clarence had loaded the six-pounder with

grape, and had laid the gun to sweep that part of the position the mutineers

would be bound to approach, ere they could attack the entrenchments. He

obtained permission to remain to fire that gun himself. Val and Dana were

told off to fire the cannon, which defended the entrance. Yunacka was here,

there and every where, it being found impossible to restrict him to one

spot. Such was the state of affairs at the time when the attack commenced

in real earnest. Nothing could be better than the way in which this was

managed. Before actually attacking the entrenchments the rebels halted

and commenced to fire from behind any cover they could find. Acting on

Fitzmaurice’s advice, his men did not return the fire, but kept well under

cover, waiting until he gave them the word. He stood erect in the trenches,

looking at the movements of the rebels through his glasses, apparently

bearing a charmed life, for the bullets flew harmlessly past him. What

he wanted was to get the wretches within range of the six-pounder, when

great execution might be looked for. Suddenly both field-pieces belonging

to the enemy fired simultaneously, and several were sent up.

“Look out, Dana,” said Val, clutching his port-fire; “that’s a signal.

They’re coming.”

Val was right — it was a signal, for with cheers the enemy came on from

both sides, fully determined to carry the place by assault. A score or

more dusky forms rushed to the entrance, and opened fire on the gunners

as they stood by the guns, port-fire in hand.

“Number one — fire!” shouted Fitzmaurice, in clarion tones.

Bang! went Val’s gun, and the score or more of rebels were reduced by

about two-thirds. This was followed by the sharp report of the six-pounder

from the housetop, when a shower of grape swept among the mutineers with

fatal effect, scattering death and dismay around. Shrieks and cries of

agony mingled with the sounds of musketry and the boom of cannon; the work

of death went on bravely, as did that of resistance.

“Number two — fire!” shouted Clarence, who had rejoined the defenders

in the trenches.

Dana’s port-fire did its work. Yunacka’s face was a study as this work

went on, men being hurled into eternity as ruthlessly as if they were so

much vermin.

He fired off his musket and then not caring to reload, waited till the

man nearest him was ready to fire, and then snatching his musket from him,

picked off his assailant. To do the sepoys justice they fought bravely

for a time, some of them actually leaping into the trenches, only to be

shot down or bayoneted by resolute men, who knew how to defend themselves.

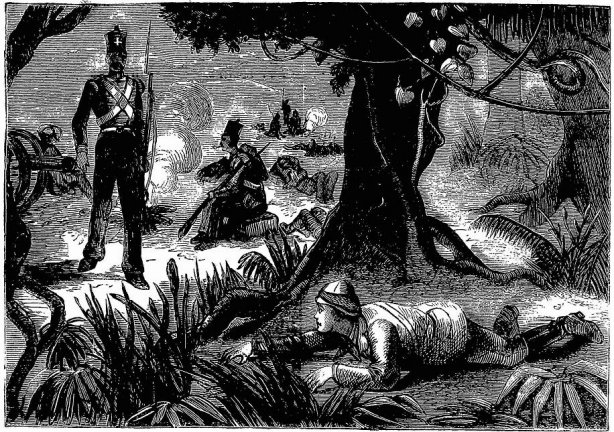

The Sepoys fought bravely, leaping into the trenches

only to be shot down or bayoneted.

It was impossible to reload the cannon, which were quite exposed, without

risking the lives of every one engaged in the service. They had done their

work, however, for small heaps of dead lay about, and the cries of the

wounded were grievous to hear. Dana was as steady as a rock, with Val and

Clarence at her side ready to sell their lives dearly for her.

A gigantic sepoy, with the sergeant’s chevrons on his arms, animated

his comrades to the attack. They made a rush towards the spot where Dana

and her comrades stood, charging with fixed bayonets, and firing as they

came on, without taking aim. It was a sight sufficient to try the nerves

of a strong man, much less those of a girl of Dana’s age, who ought really

to have been at school, instead of facing death in this heroic way. Her

cheeks did not blanch as she singled out the giant and fired. Unluckily

she missed him. Quietly appropriating Val’s revolver, which lay close at

hand, she fired just as the sergeant was within a yard of her. The shot

struck his arm, and he dropped his musket as if it were too heavy for him.

This so excited her that she jumped out of the trench and shouted “Charge!”

much to Clarence and Val’s surprise, who were altogether unprepared for

such a move on her part. However; nothing remained for them but to support

her, even though she was acting madly in leaving the comparatively safe

shelter of the trenches. Fitzmaurice caught sight of Dana from where he

stood and immediately saw her danger. He rushed forward, just as Val and

Clarence leaped out of the trench. Like a plucky little heroine that she

was, Dana thought not of the danger, now that she was in the thick of it.

She saw only wild beasts before her; things that were to be destroyed;

not human beings with loving hearts, to be treated as her fellows. The

gigantic sergeant seeing her defenceless, as he thought, seized her, but

not before she had wounded him again. Squeezed in his strong arms, she

struggled helplessly, and then became insensible.

“Defend my retreat,” the fellow shouted hoarsely to his comrades, as

he bore her away, right before the very rifles of those who would have

given life itself for her.

Dana was torn away, leaving Clarence mad with rage, and Val furious,

and her father calm and silent, but with a sharp pain at his heart. A pistol

in one hand, a sword in the other, Fitzmaurice threw himself against the

human bulwark that stood between him and his darling child. The bright

blade flashed, and each time it descended dripped with human blood. Val

and Clarence, too, were stabbing and thrusting with their bayonets, silently

and vengefully; with clenched teeth and bursting hearts; never a word spake

they, as they followed up their foes silently, ruthlessly. They were joined

by Golob and a number of others, when a desperate hand-to-hand combat ensued,

but in vain; they were compelled to retreat step by step.

“Val — Clarence; to the housetop!” shouted Fitzmaurice hoarsely. “The

six-pounder — grape — vengeance — Dana!”

With face begrimed by powder and gory hands, he issued his commands

for vengeance. The pair sprang up the stairs and reached the roof. Clarence

rammed home with a will, while Val covered the vent with his thumb, already

blistered with the heat of the iron. A heaving mass is outside the entrenchments;

Custonjee is bringing up reserves of men. But the way is blocked by that

man whose avenging sword descends with such unerring effect.

Fitzmaurice’s little band of heroes fought bravely and well, and when

the last man of the enemy was driven, out to die beyond the threshold with

a bayonet stab in his very vitals, a ringing cheer of victory went up to

heaven. The pitiless hail of iron from the roof went crashing like a mighty

wind through that mass, rending and tearing, and casting down in its awful

fury. It struck the hard ground, too, and rebounded, striking down wretches

on all sides.

On this side of the defences the battle is won; how goes it on the other?

Bravely, too. No craven heart or weak hand defends the pass; no traitor

will sell the right of way for gold. No; he that would pass that way must

do, so at his peril — must meet heroes in a death struggle, and prove himself

a better man than they.

Mutineers, mad with “bang” (a drink made from rapeseed, which maddens

to fury) rushed on the bayonets’ point, and leaped into the trench, only

to die.

But their soberer comrades shrank from following their example. Presently,

an odd sound mingles with the din of battle. A tigress was at large. Maddened

by the noises, the animal had burst her cage door open, and was hastening

to the scene of strife. How she licked her lips and glared at the prospect

of the feast which she meant to indulge in. Little recked the mutineers,

as they fired from behind bush or tree, that a tigres[s] had come to take

a part in the battle. With a roar and a bound she was upon an unfortunate

wretch who was in the act of firing. He would never draw trigger again

or bite a cartridge. In a moment he lies bitten through the neck, dead,

while that savage tigress drinks his warm blood, and growls over the draught.

Yet another victim falls before her, and then the mutineers realise this

new danger for the first time. They took to flight, but not to a place

of safety. They had climbed over a stockade by the help of a ladder.

How were they to get back without its aid? They were in a trap.

“Let me mount on your shoulders,” said a man to his comrade, who dearly

loved him. “If I get over, I can push the ladder up, and then you will

all be saved. Quick! let me mount on your back.”

“Promise faithfully, Hassan, that you will not desert us. Do you promise?”

“Yes, faithfully, solemnly.”

Hassan was soon at the top, and, trembling with joy, dropped down on

the other side. Would Hassan be true to his friend, to his comrades, and

help to save them? Why should he concern himself about them?

“Hassan, your promise,” said the voice of his friend, from the other

side.

“I cannot move the ladder by myself,” he said. “Send me help.”

He well knew that inside that trap would be found no one willing to

let his comrade pass out through any help of his.

“Here,” said Hassan’s friend to a comrade, “there is a way of escape

for us all.”

“How — where?”

“Stoop, and let me mount your back.”

“Not I. Do you take me for a fool? I am younger than you, and want to

live.”

“There are ladders at the other side.”

“I will fetch them then. Help me.”

High words then ensued, epithets were hurled at each other, and from

words they came to blows. In a few minutes they lay glaring at each other,

fatally wounded, while Hassan, poltroon that he was, stood by the ladder,

and could have saved them both. But Nemesis was at his side. Coiled up

in some long grass was a huge cobra.

“I cannot raise the ladder,” he cried.

His friend heard his voice, and with his dying breath murmured —“Traitor,

I curse you.”

Hassan stepped aside, and in doing so, trod on the cobra, whose poisonous

fangs were instantly fixed in his flesh. The wretched man looked down at

the reptile with terror-laden eyes. Too well did he realise the doom which

was in store for him. The stupor of fear passed away, and he looked wildly

around for help. None could aid him. He would run to camp. Perhaps some

one there knew of an antidote for a snake bite. People had been saved;

why not he?

Taking to his heels, he ran with the energy of despair. His feet seemed

wings, so fast did he run. He was soon in the camp; his comrades were there.

Was that an angel in their midst, that beautiful girl? This was Dana,

a captive in the midst of a rude soldiery, suffering under a severe defeat.

Custonjee was there, the calmest and most collected of all, weighing well

in his mind what the result of Dana’s capture would be. Even now the ruffians

were debating among themselves as to how they should dispose of their prisoner,

without reference to Custonjee’s wishes in the matter.

Hassan, in his terror and delirium, pushing his way to her side, threw

himself before her, crying, with uplifted hands —“Save me; I am dying.

A cobra has bitten me.”

One look at the poor wretch’s pallid face, on which the clammy dews

of death were gathering, proved the truth of his assertion.

“Heaven alone can save you,” she replied. “I can only try. I know of

a herb that is an antidote. Let me find it.”

“Stand aside, and let the girl pass,” said Custonjee. “If she can save

Hassan, let her. Do you hear there, you fellows? Stand aside.”

He drew his revolver. The trigger clicked ominously. The fellows looked

at each other. But no one cared to stop the girl, especially as it involved

receiving a bullet through the brain. Custonjee was notorious for keeping

his word. They fell back and gathered in small groups to mutter threats

with scowling faces.

As soon as Dana was free, she searched among the grass for the herb

she wanted, and having found it, made it into a poultice, and placed it

on the wound. She also made Hassan drink half-a-pint of “darrhu” (country

whisky), and then, ordering him to be wrapped in several blankets, told

him to go to sleep, which he was not long in doing, for one characteristic

of a snake-bite is to induce drowsiness, ending in a comatose state, then

death.

Meanwhile the fight had ended, the garrison being victorious, whilst

inflicting heavy losses on the enemy, whose dead lay thick in places. On

Fitzmaurice’s side three men only were killed, but the list of wounded

was larger. Val, Clarence, and Fitzmaurice were each wounded, but only

slightly, which luckily did not necessitate their laying up. Golob was

untouched, although he had exposed himself throughout the brilliant affair.

But a sadness sat on each face, in spite of their glorious victory. Did

they mourn the brave fellows who lay taking their last sleep? No; they

died like heroes, with arms in their hands, their faces to the foe, and

were to be envied, not mourned. Dana, the light, the sun, of the jungle

home, was a prisoner in the hands of ruffians who knew no mercy or pity.

They cared not to look at the poor father’s face, it was so full of

silent anguish. Val sat moodily aside, his head buried in his hands.

“Sir,” said Golob, addressing Fitzmaurice, “a number of the enemy are

still in our grounds. What are we to do?”

“Kill every one. Come, let us slay them,” said Val, looking up, with

hatred depicted on his usually good-natured face.

“Peace, lad,” said Fitzmaurice sadly; “let us teach the rebels a lesson

of humanity. No man shall be butchered in cold blood.”

“Exchange them for Dana, then,” said Val, unabashed by the rebuke.

“Good; Val Sahib, speaks well,” said Golob, with an approving nod.

“Yes,” said Clarence, “we can send a flag of truce. I’ll make one of

the party.”

“And I another,” said Val.

“Golob too,” put in the huntsman.

“I give the matter into your hands entirely,” said Fitzmaurice, with

a weary sigh; “do as you like. Heaven send that I be not bereaved of both

my children.”

Clarence and Val looked at each other significantly, as much as to imply

that grief had begun to turn their chief’s brain. The task of making prisoners

of the fellows who were in the trap they had made for themselves was an

easy matter. In fact they could hardly believe that their lives were to

be spared, they themselves were so cruel and implacable. Lutchman, Custonjee’s

lieutenant, was amongst the prisoners, all of whom were disarmed and placed

under guard.

The great difficulty now was in disposing of the enemy’s dead. The

natives belonging to the garrison did not care about touching them, and

it was impossible that Val or Clarence could dig a trench large enough

to hold the corpses.

“Set the prisoners to work,” Clarence suggested; “it will never do to

allow the bodies to remain where they fell. We shall have an epidemic if

we do.”

Lutchman could not object when the matter was mentioned to him, although

it was plain he did not like the suggestion. His men were put to work to

dig a trench outside the position, and when it was finished the dead wore

placed in it, and the earth closed over them for ever. The garrison’s dead

were interred in the ground, under the shade of a tamarind tree, a mark

being placed over the grave. The wounded were the next care, and here Fitzmaurice

and his comrades were sadly at fault, inasmuch as there were cases necessitating

amputation, which none could deal with.

The simpler cases were put right, and then Golob, Clarence and Val started

with a flag of truce. Among the dead was a bugler, whose instrument Val

took, as he had learnt all the calls by heart. When they had come in sight

of the enemy’s sentries Val placed the bugle to his lips and blew three

sharp blasts.

Val placed the bugle to his lips, and blew three sharp

blasts.

It was an anxious time for the little party; they might be fired on

treacherously.

CHAPTER XXVII

The brave fellows who had gone forth under a flag of truce, carried

their lives in their hands, for they had to deal with miscreants, and not

honourable men who acknowledged the rules of civilised warfare. Yunacka,

who had followed them unperceived, now dropped from a tree and joined them,

looking well pleased. Another unexpected visitor also appeared in the shape

of Azraal, the cheetah, which had hitherto, or at least since the commencement

of hostilities, been confined to the bungalow, to keep it out of harm’s

way. It had got out by some means, and, not finding its mistress, followed

her by scent, and came up with the party just about the same time as the

wild boy. The pair knew each other thoroughly, and immediately fraternised,

commencing a game of romps with great animation. Meanwhile the sentry had

shouted for the officer in charge of the guard, as no one had appeared

in answer to the bugle call sounded by Val.

“Try again,” said Clarence to him. “I don’t like the look of things

at all.”

Val blew another call, when Custonjee and a few of his men came forward

to see what was the matter. He understood what the white flag meant; and

told his people that the little party was not to be molested, but were

to be escorted to the camp, which was done. A queerer procession could

hardly have been seen than the one which now filed along, Golob leading,

and Yunacka mounted on the cheetah’s back bringing up the rear. The mutineers

turned out en masse to see the strange sight, and were not complimentary

in their remarks. The losses they had sustained made them feel spiteful,

and they longed to imbrue their hands in the blood of the unarmed persons,

who had, under the protection of a white flag, placed themselves in their

power. Dana’s eyes glistened with delight at sight of her friends, who

were no less pleased that she was safe and apparently unhurt. No communication

was allowed between them, however; but Azraal and Yunacka knew no restraint,

nor did they think of asking anybody’s permission to show Dana how much

they loved her. It was a touching sight to see the cheetah on its hind

legs, and with its paws round the girl’s neck, while Yunacka waited impatiently

for her to notice him, going so far as to try to push the cheetah away.

Custonjee, as commander of the rebel forces, carried on the conversation

in English, which he understood thoroughly, it being his wish, as he did

not want his men, who stood listening, to understand the nature of the

negotiations.

“You can have your lieutenant and all your men who are our prisoners

back again in exchange for Dana and Harry Coverdale,” said Clarence. “That

is a fair offer enough, and we will benefit by it more than you. The girl

is here, as you see, but the lad made his escape. I don’t know where he

is. I wish I did.”

“Major,” said Val, “will you swear by the sacred water of the Ganges

that my dear friend, Harry, is alive?”

“I wish I could, Val Sahib. All I know is that he was not injured by

us. I do not wish him to fall into our hands again. He killed one of my

men before he went off.”

“Understand one thing, major,” said Clarence, “and don’t think it a

mere threat. If Dana or Master Harry is put to death every man of yours

dies. We will treat them well, unless you force us to proceed to extremities.”

“Can’t you permit us to speak with Dana?” asked Val. “She can’t escape,

you well know.”

“I see no objection. You can talk to her, Val Sahib, but your comrades

had better not take part in the interview. The temper of my men is so uncertain,

and none of you are armed.”

Val, glad of the permission, walked to where Dana stood.

“Is my father well?” she asked, in a voice which was husky with emotion.

“Yes; he sends his love, Dana, and hopes to see you soon. We have come

to negotiate an exchange of prisoners. Custonjee is willing.”

“But he is powerless if his men object, Val, the danger to me is greater

than you imagine. I shudder to think of what may befall me.”