CHAPTER I

One very hot day, I found myself in the heart of an Indian jungle,

in company with a great chum of mine, Valentine Aubrey.

My name is Harry Coverdale, my age fifteen, my profession that of a

rover in search of adventure. My mother is dead, my father disappeared

mysteriously when I was quite an infant, and has not been heard of since.

I have neither brother nor sister, and no relative except an uncle and

aunt, who have been parents to me, and very kind to boot. Val and myself

were jaded and tired, as we had walked some distance under a burning sun,

and having found a convenient tree threw ourselves on the ground beneath

it to rest. We were fully armed, as it beho[o]ved us to be, considering

we were trespassing on the demesne of tigers, leopards, cheetahs, bears,

hyenas, snakes, etc., one and all enemies to man.

“Harry,” said my companion, “we’ve lost our way it seems. What shall

we do when night comes on?”

“Do?” I replied; “why, lots of things. Climb a tree, light a fire, and

keep watch in turns. I’m not at all afraid of the prospect, Val; in fact,

I rather like it. Camping out for the night will not hurt us. It’s just

the time for tumbling across tigers. I long to encounter one, don’t you?”

“Of course I do, Harry. But while we’re waiting for a tiger to show

itself, suppose we have something to eat?”

“By all means,” I replied, “Have you anything in your haversack?”

“Only a few biscuits, Harry. By Jingo! I’d forgotten our compact. True

to our character of hunters, we must depend upon our guns for food. They’ve

brought us precious little as yet, though.”

Big with expectation of bagging all kinds of game, we had come away

from home with nothing in our haversacks but a few biscuits, tea, coffee,

and sugar. Val and I had spent many hours in talking over our plans in

secret. We had purchased two splendid rifles out of our pocket-money, and

lots of ammunition, too, so that we were well prepared for our hunting

campaign. Nor had we neglected to make ourselves proficient in shooting,

which we accomplished by practising frequently at the military firing-butts.

To test our efficiency, he and I spent one entire moonlight night in search

of hyenas. We bagged one, but nearly lost our lives in doing so,

the brute was so ferocious.

“Val,” I said, after a minute’s pause, “I’ve an idea.”

“So have I,” he said, with a rueful expression. “Mine is that I’m awful

hungry.”

“Mine is,” I replied laughing, “that we’d better go heads or tails to

see who’s to go in search of game, while the other stays here to light

a fire, in readiness to cook when it’s brought.”

“Agreed,” he said, springing to his feet, and producing a rupee. “You

call to me.”

The coin spun in the air, and I cried “a head!” and won.

“I’ll be the hunter, you the cook,” I remarked, as I shouldered my rifle.

“You’ve got the flint and steel, Val, and there’s plenty of wood about.

Good-bye; I won’t be long.”

I felt no fear, although danger lurked on all sides. I longed to meet

a tiger face to face, feeling confident that I could hold my own with him.

Why should I be afraid of a tiger, when I was armed with a splendid rifle,

which I knew how to use? In addition to this I had a revolver, and a formidable

hunting-knife; so on the whole I was fully prepared for any emergency,

as was also Val. I sauntered slowly along, turning my eyes warily to the

right and left, and quite enjoyed the beauty of the scenery and its surroundings.

Birds of bright plumage flittered hither and thither in the brilliant sunshine,

looking like masses of jewels.

Squirrels climbed the trees, and chased each other in play along the

boughs and branches, while occasionally the head of a monkey peeped out

of a leafy cover to reconnoitre as I passed. A murmuring streamlet went

merrily on its way, from which I drank a delicious draught of water. Cocoanut

palms grew hereabouts in numbers. Mango and guava trees, full of luscious

fruit, were within my reach, and I helped myself, and enjoyed the feast

amazingly. The occasional his of a snake smote my ears.

However, as I wore Wellington boots I did not fear them much, although

at the same time I did not wish to be bitten, even through leather. Centipedes,

scorpions, and tarantulas were to be found in the hot sandy soil; in fact,

the place teemed with nasty creatures, whilst outwardly it appeared a veritable

paradise, the trees being decked with brilliantly-hued flowers of gigantic

sizes, which dazzled the eye by their beauty. I caught sight of a solitary

deer, but, before I could fire, it bounded out of view, much to my annoyance

and disgust, as I would have liked to have taken its carcase back to Val.

“Halloa!” I said aloud, as I saw a splendid peacock perched on a bough;

“what a beauty! I’ll have you for dinner if I can.”

I raised my rifle, took aim, but dropped the weapon the next moment,

as I felt something brush against my right leg. Looking down I started;

a large cheetah, or hunting leopard, stood at my side, and looked into

my face with its mild beautiful eyes. It rubbed against me again, as if

it had been a tame cat, when I stroked its beautiful coat, and we became

very friendly.

CHAPTER II

Whilst I was wondering at the strange phenomenon of meeting a tame

cheetah in the heart of the jungle, I heard a silvery laugh, and a voice

which said in good English —

“Who are you? How dare you come here you boy?”

I turned to see who it was that addressed me so brusquely, but saw no

one.

“Where are you?” I asked, looking around in amazement.

Another silvery, rippling laugh was the only reply, which seemed to

come from a plantation of bamboo trees, whither I hastened. I caught sight

of a girlish figure, but only for a moment, it had disappeared the next,

nor could I follow without making a considerable detour. The cheetah was

near me, but on hearing a shrill whistle it bounded away and disappeared.

I was lost in wonder. It appeared to me such a mystery to be addressed

in English in these wilds, and that the speaker should be a girl. Although

I was disappointed at not being able to meet the mysterious personage face

to face, I was consoled by the fact that Harry and myself were not quite

so much alone as we imagined.

“She must have a house somewhere hereabout,” I thought; “and we’re bound

to meet her later on. Won’t Harry stare when I tell him my adventure?”

I had almost forgotten my errand, or that a hungry companion awaited

my return with impatience, when a splendid stag walked leisurely from covert

to the rivulet, and drank freely. It was a noble animal. I took careful

aim and fired. The brute staggered, and lifted its head high in the air;

when, fearing it might be only wounded and would escape, I rushed forward

without waiting to re-load, eager to secure such a noble prize. But before

I reached it I heard a roar, and saw a bright mass fly through the air.

The stag was down, and bestriding it was an enormous tiger.

The whole thing was sudden and unexpected. I was annoyed at the loss

of what I considered my property. The tiger paid no attention to me, but

busied itself in tearing pieces out of the stag, which still lived. Snatching

the revolver from my belt, I rushed forward and confronted the monster.

The brute fixed its eyes upon me, and transfixed me with its glance. I

had no more power to move or speak than if I had been turned into stone,

but my thinking faculties were not suspended. The tiger appeared to me

the most beautiful object I had ever seen; its striped satiny coat looked

like some much burnished gold inlaid with jewels, and its eyes gleamed

like emeralds, whilst it horrid fangs assumed the form of beautiful ivory.

But although I was fascinated, I had an undefined sense of horror upon

me which seemed to hold me back, and made my whole frame shiver as if I

was attacked by a fit of the palsy.

The revolver fell from my nerveless grasp, and I stood defenceless and

at the mercy of the cruel brute. There was a sound like thunder in my ears,

followed by the report of a rifle, which had the effect of rousing my dormant

faculties. I saw the tiger in its death agonies, crawling towards me, when

I instinctively snatched up my revolver, and fired the barrels in quick

succession. Each shot must have taken effect at such a point-blank range;

but so tenacious was the brute of life that even in its last extremity

it reared on its hind quarters and tried to claw me down, falling dead

in the very act.

In its fall it struck against me and sent me over like a ninepin; but

I soon regained my feet, and looked round in the expectation of seeing

Val, for who else could have fired the shot which saved my life? But neither

Val nor any one else could I see. Placing a pocket bugle to my lips I blew

a call as a signal to Val that I needed his help. I listened for his answering

call, but heard only the echo of my own in the direction of the bamboo

plantation.

“Ah!” I murmured, as a light broke in upon me. “I know who my preserver

was — the mysterious stranger. I wish I could thank her.”

As Val had not yet replied, I repeated the call, which was answered

this time; and in a few minutes he dashed up to my side.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

Then, as his eyes rested on the dead tiger, he continued —

“Harry, you were in luck when you knocked such a splendid fellow as

that over. How did you manage it?”

“I only came in at the death,” I replied, in sporting phraseology; “the

credit is due to some one else.”

“Who?” he asked quickly.

“I don’t know. I wish I did.”

“Not know? Nonsense, Harry; it seems incredible that anybody could have

fired and knocked the tiger over without you seeing him.”

“It wasn’t a ’him’ at all,” I said.

“You’re only chaffing,” he said, somewhat hastily. “It isn’t fair, Val,

when I’m so eager to know all about the matter.”

“We can’t eat the tiger, Val?” I said.

“Who said we could,” he replied. “I wish I had won the toss, and come

out instead of you. I’d have bagged something to eat before this, I know.

But tell me, Val, who was it that fired the shot?”

“I don’t know, I have my suspicions. If you will listen patiently I’ll

tell you all I know of the affair.”

When I finished my narrative, he said —

“Harry, you ought to have followed her. We want food and shelter. Surely

no one would be cruel enough to refuse us either under the circumstances.”

“She evidently did not wish me to follow her,” I replied; “and I’m sure

neither of us would care to force our company upon her; besides there may

be other people for her to consult — a father and mother for instance.”

Val was evidently disappointed. We cut off portions of the deer in silence,

being too much engrossed in our own thoughts to converse. Secretly I longed

to see the girl who had saved my life, and around whom I began already

to weave a web of romance.

“And was it a tame cheetah?” Val asked, as we trudged to our bivouac,

carrying a goodly portion of the carcase slung across a bamboo which we

had cut from the plantation.

“Yes, and such a beauty. Look, here it comes again.”

Something much resembling the friendly cheetah bounded towards us.

My companion dropped his end of the bamboo in alarm, and stood on the

defensive, revolver in hand, saying —

“It’s all very fine, Harry, but it may not be your cheetah, but a wild

and ferocious beast.”

We were very near the plantation at the time, from which a girlish voice

said imperiously —

“Drop your weapon, boy, or I’ll fire.”

“Halloa!” exclaimed Val, “there she is. I’ll find her, and see what

she’s like; so here goes.”

And he ran towards the spot from whence there suddenly came the sharp

crack of a rifle, which brought him up suddenly. The bullet went clean

through the top of his cork helmet. Then the same voice spoke in Hindoostanee,

the cheetah rushed at Val, bore him to the ground, and stood over him,

growling viciously.

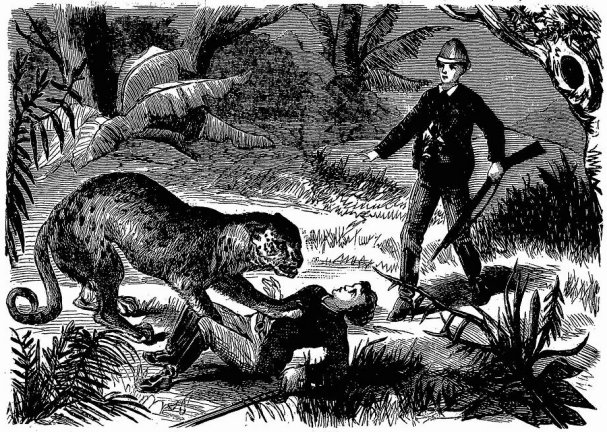

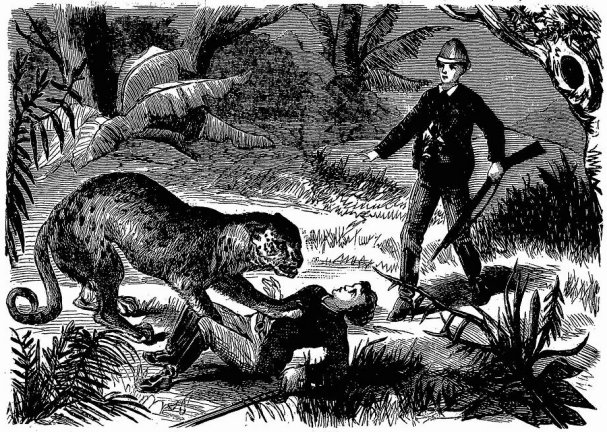

The cheetah rushed at Val, bore him to the ground,

and stood over him.

CHAPTER III

I was at a loss how to act. My duty was to help Val; but in doing so

I would only jeopardise his own safety and mine. In sheer desperation I

appealed to the girl in her place of concealment, saying — “Please call

off your cheetah; my friend did not wish to harm you.”

“Harm me!” was the contemptuous rejoinder; “let him dare try, and see

how it will end for both of you.”

“Val, say you are sorry,” I said to him.

“Shan’t,” he replied; “I’ve done nothing. I’m an English boy, and have

as much right to be here as any one else.”

“But it isn’t your place. Why don’t you go home and stay at home? That’s

the proper place for you,” said the voice.

“I’ve as much right here as any one else,” said Val, raising his head

defiantly, only to pop it down again on receiving a warning growl from

the cheetah.

A silvery laugh came from the plantation, and a death-dealing rifle

was covering him, no doubt.

“I’m a boy,” cried Val, “and if you were another I’d give you a good

licking for setting a brute like this on a fellow; it’s cowardly, and despicable!”

“Are you afraid?” was the question, laughingly put.

“Not exactly, but I don’t like it. Would you?”

“Perhaps not. Azraal won’t hurt you if you are quiet.”

“Thank you for nothing. Why don’t you go home to your mother instead

of setting beasts on others?”

“I have no mother,” said the voice sadly; “I never knew a mother’s love

and care.”

“I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings,” said Val, who was one of the

kindest-hearted fellows alive. “Forgive me if I have pained you.”

She spoke to the cheetah in the native tongue, when it lay down beside

Val and offered him its paw in token of friendship.

“That’s better,” said Val, as he assumed a sitting posture, and shook

the friendly paw. “I’m quite well, thank you; how are you?”

“Boy, are you fond of sweetmeats?” cried the voice.

“Rather.”

A large packet fell at his feet, which he opened, saying —

“Come on, Harry; they’re fine — splendid. I say, miss,” he cried, after

he had eaten several, “have you a brother? because if you haven’t, Harry

and I will be your brothers. We’ll teach you to lick anybody that behaves

rudely to you.”

“Thanks,” she replied. “I’ll think about it; but I say, can you shoot?”

“Well, yes. I’m on the look-out for a tiger. He won’t live long when

I meet him.”

“Don’t be so sure of that; but tell me could you shoot a guava off my

head?”

“Perhaps. I’d like to see you first, though,” said Val, with a grin.

“Would you mind my shooting at a guava placed on your head, eh?”

“You might miss, you know.”

“Bah! I never miss. Your friend wouldn’t be alive now else; he was in

the way, or I’d have killed the tiger with a single shot.”

“I don’t mind being your target,” I remarked.

“No, no,” she replied; “you might get nervous. But Azraal, my pet, whom

I love dearly, shall. There’s a guava; place him a hundred yards away,

and put the fruit on his head.”

“He might object.”

She laughed, and gave her commands to the cheetah, which followed me.

Judging the distance as well as I could, I placed the guava on its head;

the beast remained in a statuesque position, neither moving, nor hardly

breathing.Val and I stood aside out of the line of fire, curious to learn

how she would acquit herself. A sharp ringing report, a cry of triumph,

and the guava fell to the ground, pierced through the very core. We were

loud in our praises, and Val addressed her, but received no answer. She

had evidently gone, as silently as she had come, leaving us full of astonishment.

“I wonder who she is?” said Val.

That’s all we could do — to wonder — for there was no doubt she did

not intend to satisfy our curiosity, for the present, at least.

We shouldered our burden and made our way back to our bivouac, which

we reached without further adventure.

“Here’s the meat, Val,” I remarked, as we put it down; “the next thing

is to cook it.”

“That’s easily done,” he said. “I’ve a cookery book,” producing a well-thumbed

volume; “but where’s my haversack?”

It was nowhere to be found, and we were wondering who could have taken

it, when Val said —

“By Jingo, the monkeys have stolen it. Look, there’s a whole troop of

them under yonder tree. One of them’s got inside it, and is rolling about.”

“Let’s get as near them as we can and watch the fun,” I said.

“Fun,” said Val, in a grumbling voice; “where’s our tea, coffee and

sugar by this time, I’d like to know, and the snuff which I brought as

a present for Golob, the shikaree,” (native huntsman).

“Let’s hope for the best,” I said, as we made our way cautiously in

the direction of the thieves.

We gained the cover of a tree close to where the monkeys were, and watched

their tricks, breaking out frequently into hearty fits of laughter. The

various packages had been opened, and were being examined by the monkeys,

that containing the loaf sugar being in special request. The fights and

squabbles that occurred over these toothsome lumps were extremely ludicrous,

and mirth provoking. The big monkeys chased the smaller ones, and forced

them to disgorge their booty, amid shrieks and cries. No sooner had one

fellow stolen a piece from another, that he was chased in turn. The violent

efforts that were made to swallow the prize before it could be wrestled

away, and the grimaces accompanying the operation, were of a character

to move the risible faculties of the gravest. Some went so far in their

greediness as to poke their fingers into the mouths of others to abstract

the sugar, and received sharp bites for their pains, all of which incidents

ended in a regular free fight. Those who were not fortunate enough to obtain

a portion of the sugar, turned their attention to the coffee and tea, which,

not being to their liking, was rejected. But the best part of the fun was

with the monkeys who had meddled with the packet of snuff.

They were coughing, sneezing, and rubbing their eyes alternately, so

funnily that Val and I had to hold our sides. One unlucky little imp, almost

a baby monkey, had buried its nose so deeply in the snuff as to be in a

state of frenzy. It ran to its mother for help, who, on seeing its face

smeared, put her nose close to her young one’s, and immediately went off

into a paroxysm of sneezing, greatly to the discomfort of another mite

which clung to her back. Val had brought a pocket looking-glass, and a

pair of spectacles, as a present for Golob. These were objects of great

interest, and it was laughable to see the perplexity of the several monkeys,

who got hold of them in turn. On looking into the glass, and seeing themselves

reflected in it, they invariably put their disengaged hand behind it, to

feel for the other monkey. In one instance when this was done, there happened

to be a curious imp on the other side of the glass, who resented the intrusion

of the hand by giving it a severe nip.

The spectacles were placed around the neck, on the top of the head,

and tried on every conceivable way except the right one. One fellow bit

the glass through, and gave a series of shrieks in consequence.

“I can’t stand this any longer,” said Val; “they’ve ruined the spectacles.”

Out he dashed, when the whole troop sprang into the tree, and was out

of reach in a moment. A baby monkey, however, tumbled to the ground in

its eagerness to escape, and was captured by me. The poor mite was in a

great fright and cried piteously, for its mother, I suppose. There was

a great commotion up the tree among the entire colony, of which however

we took no heed. I had some sweetmeats in my pocket, with which I fed the

imp, greatly to its satisfaction, and it soon became quite tractable.

“Look out, Harry, here’s the mother,” said Hal. “She means mischief.”

A large female monkey sprang from the tree to the ground, and confronted

me with open mouth. I threw a sweetmeat which it disdained to touch, but

made a rush at me, and bit my leg, fortunately through my Wellington boot.

I dropped the baby, which sprang on its mother’s back, and both were soon

out of sight. The commotion in the tree increased, and many monkeys assumed

such a threatening attitude towards us that I deemed it prudent to counsel

an immediate retreat.

“Come along then,” said Val, “I don’t want to be bitten; the fellows

have sharp teeth, and know how to use them.”

We took to our heels, and, looking back, saw we were being chased by

the whole colony. How the matter would have ended I cannot say, monkeys

are so spiteful, had not a diversion happened from the sudden appearance

of a tigress and her cubs.

CHAPTER IV

The tigress gave a series of roars, making the whole place resound,

which had the effect of sending the troop of monkeys off at a helter-skelter

pace to their tree. Val and I reached ours, and at once busied ourselves

in heaping lots of fuel on the fire.

“We must climb into the tree,” he said.

“Hadn’t we better try the effect of a couple of shots at her first?”

I exclaimed.

“And if we miss we’ll have to look out for squalls. No, the tree is

the safest place. We can take our guns up with us, and have a shot at her

from cover.”

“All right, I’ll give you a lift and then follow you. I can climb better

than you.”

“I’m the best climber,” he replied. “I’m not going to give up the post

of danger to you.”

A glance in the direction of the tigress showed me that she had not

seen us as yet, but the cubs were toddling towards us, attracted no doubt

by the scent of the deer’s carcase. Val sprang on to my back and climbed

from thence into the tree, when I handed him up both guns. The cubs were

within a few yards of us now, but appeared afraid of the fire, and began

to mew and growl. I soon took my place at Harry’s side. The tigress, attracted

by the cries of its cubs, came on at a smart trot.

“Now’s our time,” said Val. “Let’s have a shot at her; but mind, no

hurry. Take careful aim.”

On seeing the fire the brute halted, and uttered a peculiar cry, which

brought the cubs to her side.

“Now Val,” I said, as I ran my eye along the barrel of the rifle.

We fired simultaneously, wounding the tigress and shooting one of the

cubs dead.The tigress roared and lashed her tail in a furious manner; and

then, seeing the lifeless from of one of her young, caressed it, and tried

by various means to arouse it.

“I haven’t the heart to hurt her,” I said. “Poor brute, how she must

be suffering! Let her go.”

“Nonsense, Harry. I’m hungry and want to get down from here to cook

the dinner,” said Val.

We fired and wounded the tigress again, which so infuriated her that

she made a rush in our direction, entirely disregarding the fire, of which

wild beasts are most afraid. Catching sight of us she sprang over the flames,

and began to climb the tree as nimbly as a cat. We poured in a simultaneous

fire at point blank range. She tumbled backwards, and fell into the fire,

but was quickly up again, with a singed coat.

Unluckily, Val lost his balance and fell headlong to the ground at the

tiger’s feet. The brute seized him as a cat would a mouse, and trotted

away with him in her mouth, followed by her cubs. Val’s danger aroused

me, and I descended the tree, resolved to follow the brute, rescue my friend,

or perish by his side.

Unfortunately I had her hind quarters only to aim at, and I might miss

her and hit my friend. I would have given my life freely to save him. But

I kept myself cool for his sake, feeling that everything depended on my

doing so. I suddenly recollected that I had not loaded my rifle. Hardly

had I rectified this oversight that the tigress halted, and this gave me

a fair mark for taking a deadly aim, which I resolved not to throw away.

I fired from a kneeling position, and uttered a cry of joy when she dropped

Val, staggered backwards, and made off with her cubs.

“Ah, ah!” I muttered, “it will take you all your time to digest those

leaden pills.”

I was at Val’s side the next moment, peering into his face, anxious

to ascertain if he still lived. He had only fainted, and I busied myself

in bringing him to. I obtained water from the adjoining rivulet, and bathed

his face and temples, administering, too, a small quantity of brandy from

my flask. These measures had the effect of restoring him to consciousness

after awhile.

“Halloa, Val, dear old fellow,” I said, “how do you find yourself now?”

“All right,” he said, sitting up; “why do you ask? Isn’t it time for

dinner eh? I am so hungry.”

“But are you hurt, old fellow? Don’t you recollect the tigress carrying

you off?”

“Ah,” he said, “so she did; but after she had given me a shake or two

I went off into a stupor.”

“Which might have ended in death,” I remarked; “but thank Heaven you

don’t appear to be at all hurt.”

“Nor am I, Harry. She must have carried me by my clothes. She wasn’t

such a bad tigress after all.”

“I believe you’d have your joke if you were about to be executed,” I

remarked. “Let’s get back to our tree, old fellow; we’ve got to cook our

dinner, don’t forget that.”

He got up and leaned on my arm for support, for he was much shaken in

nerve and body. When we reached the bivouac I prevailed on him to lie down,

whilst I busied myself in cooking the dinner. I hurried to the bamboo plantation

and began cutting down two stout sticks. Suddenly I heard a loud hiss,

and turning, saw an immense cobra, with distended hood. At the same moment

I heard a rustling in the grass, and turning my gaze there, I gave a loud

shout of joy.

CHAPTER V

A welcome sight met my gaze, although it was nothing but a little creature

resembling a ferret somewhat in size and appearance. But I recognised in

the mongoose a friend in need, knowing it to be a determined enemy of snakes

of all kinds. I had often seen it exhibited by snake-charmers, but never

before had an opportunity of seeing it in its wild state. I lost all sense

of fear now that an active little ally had come on the scene, one which

I felt assured would not fail me. The cobra recognised its enemy, which

flew at it and pinned it by the head with its sharp teeth, and held on

to it with the tenacity of a bull-dog. The snake tried to shake the animal

off, and, failing in this, wound its coils around it until little more

than its head and tail were left uncovered. The struggle was soon over.

Victory declared itself in favour of the plucky little mangoose, which,

as soon as the snake uncoiled itself and lay dead, ran away and was soon

out of sight.

The whole affair did not last more than a few minutes, and seemed unreal

but for the evidence before my eyes—the body of the cobra, which measured

over four feet, and was as fine a specimen of the class as I had ever seen.

I made a slit in a bamboo cane, and took the dead snake to show to Val,

who hated all its species heartily, and was never better pleased than when

destroying them himself, or seeing them destroyed.

“That’s a real whopper, Harry,” he said. “Did you kill it?”

“No, but a friend of mine did.”

“Ah, I know, our little friend.”

“My little friend saved my life, Val.”

“I know she did; she’d have saved mine twice over I dare say.”

“My little friend was a mangoose,” I said. I then told Val of my adventure,

when he said seriously—

“I am so thankful for your escape, dear Harry. I’m sure I’d die, too,

if anything happened to you.”

He got up, and helped to erect our cookery apparatus, and it was almost

finished when he cried excitedly— “Look, Harry, look!”

I snatched up my gun, fully expecting danger from some wild beast.

“Don’t be alarmed,” he said. “It’s only three natives carrying something

very like dishes.”

“Who on earth can they be?” I said; “and what can they want here, I

wonder? They’re making straight for us, Val.”

“Tell me something I don’t know, will you? Oh, can’t I smell something

nice—roast meat for one thing?”

“It may not be for us.”

“Just shut up, will you? Who else can it be for? You don’t suppose the

fellows have come out to feed tigers, do you?”

As this question was unanswerable, I waited for the affair to explain

itself.

The natives, evidently servants, were well-dressed, and respectful in

their demeanour. One of them handed me a note, which was addressed as follows—

“TO THE TWO ENGLISH BOY-HUNTERS.”

“I’m glad she put it in the plural, Harry.”

“Why?” I asked, in surprise.

“Because otherwise she would have meant me,” said Val.

I opened the note, and read— “DANA presents her compliments to the two

boys who are playing truant, and who ought really to go home, and begs

their acceptance of the accompanying repast. Ask my servants no questions—it

is useless; and mind, don’t forget to send back the dishes. Dana wishes

both a good appetite.”

We laughed at the quaint humour displayed by the writer, who became

more interesting than ever in our eyes. While one of the servants spread

a cloth and placed the dishes on it, another busied himself in opening

a couple of bottles of claret, which he took out of an ice pail.

“This is like what you read of in the ‘Arabian Nights,’” said Val; “and,

I say, Harry, just look at that fellow’s gun; ain’t it a stunner and no

mistake!”

The third servant was armed with a splendid rifle, and evidently meant

to guard us while we ate our dinner. Wonder upon wonder! the dishes were

of solid silver, and the plates of the finest china. The cutlery was of

the best description, and the forks and spoons real silver, and crested.

We did ample justice to the good things so plentifully placed before us,

and drank our delicious wine with thankful hearts. The native servants,

though respectful and attentive, never opened their lips, which provoked

Val’s ire.

“Why the dickens don’t the fellows talk?” he said peevishly. “We might

then learn something of our mysterious friend, especially as these men

are not aware we understand Hindoostanee.”

“Sirs, may we clear away?” said the head servant, in good English, and

with a sly grin on his face.

Val and I burst out laughing at this rebuff, for as such it was evidently

meant. We offered the servants a present of money, which they declined,

and went their way as quietly as they had come. We made up a big fire,

looked to our weapons, and prepared ourselves to pass the night where we

were. Our conversation turned on the events of the day, especially with

regard to Dana, which we thought a very pretty name.

“I wonder whether we’ll ever see her,” said Val. “I think she must be

very beautiful, and of high rank! Look at the style she lives in!”

We hazarded all kinds of conjectures about her, but that was all we

could do; the affair was in every respect a mystery. It was near sunset

when a remarkable incident occurred quite in keeping with the others which

had preceded it. An arrow fell at our feet, but where it came from, or

who had sent it, was another mystery. It was a blunt arrow, and near the

tip was a note attached with twine.

Val read the missive, which was not in Dana’s handwriting, and it ran

thus— “If you are wise seek the shelter of the fakir’ cave; or else light

a circle of fires, and don’t move out of it. Disregard this warning at

your peril. A FRIEND.”

“It’s a man’s handwriting,” I remarked, “and the writer is an Englishman

evidently. No native ever wrote such a hand as that.”

“I agree with you,” he replied. “It matters little who he is, though

he has given us good advice, which we had better act upon.”

“Decidedly, but wasn’t it rather stupid of him to tell us to go to the

fakir’s cave, a place we had never heard or dreamt of?”

“Yes, I admit that; but our present business is to make ourselves secure

from danger. Let’s set about it at once.”

We did so, and were soon bivouacing within a circle of flame, having

provided ourselves also with abundance of fuel to last the night through.

It was arranged between us to keep watch in turn, as it would be highly

dangerous for both to sleep at the same time.

CHAPTER VI

“I’ll stand sentry first, Val,” I said.

“You would be first in everything, Harry. I don’t like it, old fellow.

You think because that beautiful girl——”

“Have you seen her, Val?” I asked.

“No, but I’m sure she’s lovely. I suppose I can say she’s good-looking

if I like?”

“She’s everything that’s charming, no doubt, Val, but after all, she

didn’t save your life.”

“But you did, Harry,” and he grasped my hand warmly. “Heaven bless you,

old boy. But let’s toss up—heads or tails? Here’s a coin; call to me.”

Thinking he meant the choice of standing sentry, I said— “Heads.”

“You’ve lost, Harry.”

“All right. What have you won ?”

“The girl, of course. Good night, old fellow. I’ll give way on the other

point, Wake me early, Harry.”

Val wrapped his cloak around him, and was soon in the land of dreams.

I was keeping watch by the bivouac fires, with scores of dangerous creatures

surrounding me. My thoughts reverted to home and to the alarm which my

uncle and aunt would be sure to feel at my absence. I began whistling “Home,

Sweet Home” softly, as I made the fires blaze and threw more fuel on. It

was a weird scene—the lurid glow from the fire penetrated the jungle for

several hundred yards, lighting up objects sufficiently for me to recognise

them. Just beyond huge shadowy forms seemed to flit about, assuming various

shapes.

Suddenly there came a burst of melody, which seemed to me to come from

the clouds. It was the ballad “Home, Sweet Home” that floated on the breeze,

and held me wrapt in delight. Then the singer broke into a merry ditty,

which made me feel inclined to laugh and dance, and ended with a peal of

rippling laughter and a “Good night, boys.”

“Good night,” I shouted in return.

I knew who the singer was now, and longed to hear more, but there was

silence, save when a tiger roared, or a hyena laughed. Then the jackals

made night hideous, and the “toowhit” of an owl came solemnly on the breeze,

while large bats circled overhead, attracted by the light of our fire.

Some of these, the vampire species, are dangerous. A salamander lizard

came down the tree and basked in front of the fire, looking at me with

its bright intelligent little eyes, as much as to say— “Isn’t this jolly?”

My two hours were up, but I wouldn’t wake Val.

“Sleep on, old fellow,” I muttered, as I heaped more fuel on the fire.

Innumerable fire-flies hung from trees and bushes, looking like tiny lamps,

and presented a pretty sight. I had my rifle ready for use, not knowing

when I might require its services to guard both myself and my companion

from danger. As the night advanced the dews began to fall heavily, and

with a chilling effect, making my cloak acceptable, although I was surrounded

by fire. Suddenly looming in the distance, amid the fantastic shadows,

came a human form, but who or what he was I was at a loss to conjecture.

Behind him came other forms.

“What ho, there!” I shouted. You are in deadly peril.”

No answer. Was this procession one of phantoms? The foremost figure

was that of a man, tall, gaunt and with flowing locks, bearing in his hand

a staff. Following him was a gigantic ape, armed with a branch of a tree,

walking upright like a man, his black muzzle and white body giving it an

uncanny appearance.Bringing up the rear were a tiger, cheetah, hyena, and

a jackal. Not one of the party uttered a sound, although they passed within

full view of me. Astonishment kept me silent for a time.

“Who comes there?” I cried at last, but without raising my rifle.

The human figure raised its staff, and a smile stole over its face,

on which time had ploughed deep furrows, and the lips moved, as if bestowing

a silent benediction.

“Good night,” I said involuntarily.

A wave of the staff, and the procession passed into the deep shadows,

and was lost to view.

“Halloa!” said Val, starting up and rubbing his eyes. “Who were you

talking to? Her, I suppose?”

“No; I saw a procession of ghosts.”

“Ghosts? Don’t believe it. She has been here; that’s why you let me

oversleep myself.”

“You missed a treat, Val,” I said.

“I’m always missing treats. What did she say? Did she look at me?”

“No; she did not refer to you even, but I can tell you she sang divinely.”

“To you?”

“Certainly! You were asleep, you know.”

“I don’t want to be reminded of my misfortune,” he replied, in a tone

of annoyance.

“No nightingale could have sung sweeter, old fellow,” I said.

“Charming, no doubt,” he sneered.

“‘Home, Sweet Home,’ and a sweet ‘good night!’ which thrilled me through

and through.”

He suddenly awoke to the fact that I was chaffing him. I related all

that had passed, to which he listened, half incredulously.

“Go to sleep, Harry,” he said; “I mean to have a turn at all these mysteries

now. Pleasant dreams, old fellow.”

Wrapping my cloak about me, I was soon locked in sleep, and had dreams,

in which past events figured prominently.

CHAPTER VII

The mysterious girl had made a deep impression on Valentine Aubrey;

and he longed to see her, not from any ordinary motive of curiosity, but

from a conviction that they were to be mixed up in life together. Val had

a very vivid imagination, and was always on the qui vive for something

wonderful. Now that he was watching he listened, and kept his eyes well

employed.

“Why doesn’t she come?” he thought, with annoyance. “She sings and talks

to Harry when I’m asleep. Didn’t I offer to be a brother to her? It’s positive

ingratitude, and I’m disgusted. Halloa, what’s this?”

The dim outline of a human figure could be seen, hovering about in a

way that made Val feel uncomfortable.

“Come along,” he said at last, “and show me what you are like, and don’t

go sneaking about like that.”

Hardly had he spoken than there came the report of a rifle, followed

by a laugh, and a scream of terror.

“This is getting past a joke,” thought Val. “Harry had all the singing,

and I’ve come in for all the row.”

The figure he had seen came bounding towards him, head over heels, like

an india-rubber ball.

“Halloa! stop! Where are you coming to?” he shouted, stopping the uncanny

thing with the butt of his rifle, just in time to prevent it going right

into the fire. Slowly uncoiling itself, the figure first sat, and then

stood upright, revealing to Val’s astonished gaze a youth, covered with

long hair all over his body and arms, and with nails like the talons of

a bird. The face alone was human, and a pair of large intelligent eyes

looked at him half defiantly, half in terror. Val addressed him in Hindoostanee,

but received no reply.

“Blest if it ain’t just like the story of ‘Valentine and Orson.’ I wonder

whether he’s been suckled by a bear?” muttered Val.

Harry slept soundly; but Val, feeling somewhat uneasy, awoke him.

“All right, old fellow; it’s my turn to keep watch I suppose?”

“Look, Harry, look! Here’s a queer chap. What do you make of him?” said

Val.

“It’s a monkey with a human face, Val; an ugly looking creature, too.

What does he want?”

“Ask him. I spoke to him in Hindoostanee, but he didn’t answer. You

try him.”

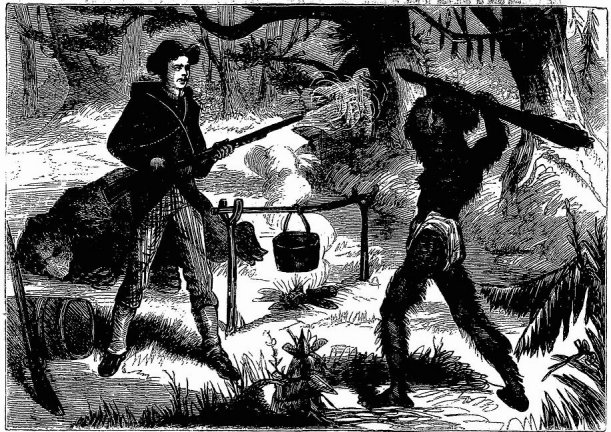

“Let’s try him with a biscuit first,” said Harry, as he threw him one.

The strange creature caught and ate it with avidity, holding out his

hand for more.Harry held out another to entice him nearer. At first he

was shy; but hunger prevailed at last, and he entered the circle of flames.

Harry held out a biscuit to entice the strange creature

nearer.

Harry patted his shaggy head, and gave him a biscuit and a few lumps

of sugar, which caused him great delight. Seeing the carcase of the deer,

he looked up wistfully at Harry and pointed.

“What an appetite the fellow has!” said Val. “Blest if I wouldn’t rather

keep him a week than a fortnight.”

Harry cut off a large piece of flesh, and raking some embers together,

put it on to broil, to the intense satisfaction of the queer-looking boy,

who smacked his lips and sniffed the odour of the cooking meat with every

sign of pleasure. Before it was quite done he made a snatch at it, and

began eating it quite hot, growling over the morsel like a cat, to the

great amusement of his companions.

“He ain’t particular, Harry?” asked Val. “What teeth the fellow has!

I hope he won’t bite us.”

“Wouldn’t he do well in a show?” said I, laughing. “We’d make a fortune

out of him, old fellow.”

“Not if he eats two or three pounds of meat at a sitting. I wonder who

he is?”

“Can’t say; evidently a wild wandering boy.”

“Let’s dub him the ‘Wandering Boy of the Jungle’ Look! he wants more

already. Why, he’d breed a famine.”

The uncouth creature was pointing to the venison; but Harry shook his

head, to intimate he was not to have any more just then. The creature cleared

the fire at a bound and began climbing a cocoa-nut tree, hand over hand,

with the agility and dexterity of a monkey.

“I suppose he’s going to roost up there,” remarked Val, “out of the

way of snakes. Not a bad idea.”

“He’s thirsty, and wants the milk. He’ll be back presently,” replied

Harry.

This proved correct, for the wild boy returned with some cocoa-nuts.

They were full of delicious milk; but the lads were at a loss to know how

he would open them. Bounding over the fire again, the wild creature returned

with a large club, evidently his weapon, and at once cracked the top of

a cocoa-nut, the contents of which he drank.

“You might crack one for us, I think,” said Val. “I’ll help myself.”

He stretched out his hand to take one, when the wild boy seized him

by the wrist, and pressed it so hard that Val danced about with pain. Val

raised his rifle threateningly, when, with a cry of rage and defiance,

the wild boy swung his club in the air. In another moment Val’s skull would

have been crushed, but I grasped the creature by the arm and shook him.

He was quiet in an instant, and knelt submissively at my feet, with every

sign of contrition. Evidently he appreciated my kindness, and liked me,

and at a sign he cracked a cocoa-nut and handed it to me.

“The sooner we get rid of the savage beast the better,” said Val. “He’s

bruised my wrist.”

“Don’t be angry, old fellow,” I said. “He knows no better, and I’m positive

he’s amenable to kindness.”

“But his hand is as hard as iron, Look at him now. He’s playing with

your gun. He’ll shoot some one.”

The wild boy was looking into the barrel, and poking his fingers down

it with a puzzled look. Turning the weapon round, he scratched himself

like a monkey does, and then examined the trigger. It was at half-cock;

he pulled hard, but it wouldn’t move. This enraged him, and he took his

club to break it, when I interfered, and, seizing the rifle, attempted

to wrest it from him. Uttering cries of rage, he whirled his club fiercely.

Raising his rifle, Val fired in the air, when the wild boy, with a shriek

of terror, bounded over the fire and was lost in the surrounding darkness.

“What do you think of your pet, Harry?” asked Val.

“Very interesting.”

“Especially in his character of ‘King of Clubs,’ eh?”

“I’m afraid we’ve frightened him.”

“That’s cool. I think he has frightened us. I don’t want to see him

again.”

The conversation, was interrupted by a voice, which came from the bamboo

plantation, saying— “Boys, what’s the matter?”

“Nothing particular,” I replied. “We’ve been amused by a wild creature.”

“No, we haven’t,” said Val, “We’ve been disgusted. But I say.”

“Well, what is it?”

“Aren’t you coming nearer so that we can see what you are like?”

“No, certainly not. Boys like you ought to be at home in bed.”

“We can give you some hot tea,” said Val. “Do come.”

“We’re very lonely, Miss Dana,” I ventured to remark, “It would be a

charity to keep us company. We can tell you a whole lot of news.”

“Indeed! Well, talk away: I can hear. Besides, I know all the news.”

“I wish I could see you,” muttered Val. “All this mystery is very bothering.”

“Shall we join you, miss?” I asked.

“No; you are safer where you are; to be in the Jungle at night means

death.”

“But you are alone,” said Val. “What a girl can do, so can boys. I’m

coming.”

“There’s a tiger yonder, boy. Look in the bushes by your light, can’t

you see two greenish orbs?”

We did as we were desired, and perceived two glowing greenish orbs,

which we took at first for clusters of fireflies. We were about to raise

our rifles to fire when the wild boy appeared in chase of a small deer

which made straight for our fire, and, brought to bay by the bright flames,

stood still. With a blow from his formidable club he felled the creature

to the earth, and then threw it on one of our fires to roast whole.

“Is that Yunacka, the wild wandering boy?” asked the voice from the

plantation.

The wild creature pricked up his ears and showed evident signs of delight.

“Yes, miss,” I replied. “Do you know him?”

“I should think so,” was the reply. “Here, Yunacka, I want you.”

He bounded away; and Val and I dragged the carcase of the deer out of

the fire.

“Look to your rifles,” cried the girl. “Yunacka may need help. Keep

your eyes on the bush.”

We saw the wild boy quickly disappear in the darkness.

CHAPTER VIII

We kept our gaze fixed on the bush, where the two balls of green fire

gleamed and scintillated. Now that we had been made aware of what they

meant we were not quite so much at our ease.

“Make the fires blaze,” said Val.

We stoked the fires, and could now see the striped coat of a tiger as

it lurked among the bushes, waiting for a chance to spring out at us. After

awhile we saw the wild boy approaching the bush from the rear, swiftly

and stealthily, with upraised club. He dealt the lurking tiger several

blows in quick succession, and when the brute turned with an angry growl

to attack him, he bounded right over it, and, rolling himself into a ball,

tumbled in our direction. The tiger left its ambush and followed Yunacka,

patting him with its paws as a cat would play with a mouse before killing

it.

“Why don’t you fire?” cried the mysterious occupant of the bamboo plantation.

“Can’t you see the poor fellow’s danger? You’re in the line of fire, or

I’d have shot the brute before this.”

Bang! bang! a roar, and a sudden uncoiling of Yunacka’s body, who raced

for our bivouac, and jumped clean in. Before we could reload, the tiger,

which was badly wounded, slunk away into the darkness.

“You had better practise shooting,” said Dana. “Bah! you call yourselves

marksmen? Why don’t you go home?”

While she was speaking, the procession which I had before seen returned,

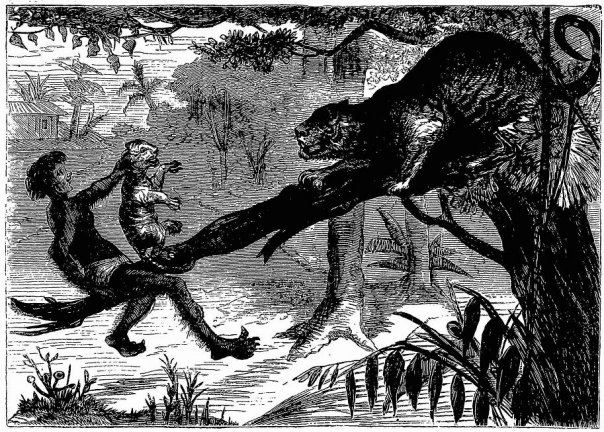

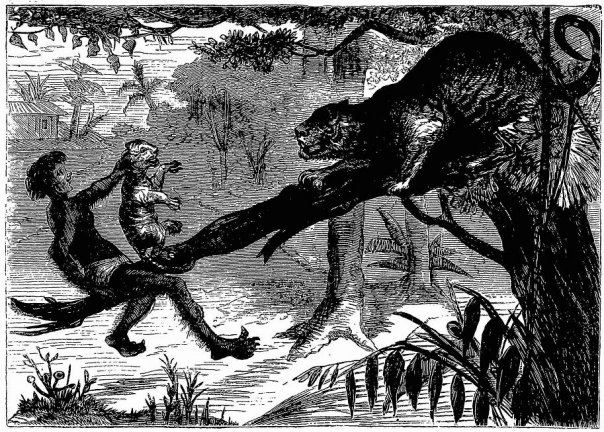

and to Val’s great astonishment. Yunacka’s rage on seeing the ape knew

no bounds; he gnashed his teeth and stamped with passion. Evidently the

pair were not friends, for the ape, on its part, was much disturbed at

sight of him, and grasped its formidable club viciously, showing its yellow

teeth. I tried to soothe Yunacka by patting him gently on the back, but

mistaking this for encouragement, he dashed out, and a fight ensued. The

fakir used his staff freely on the heads of both combatants to separate

them, but all to no purpose; they struck and tore at each other savagely.

The yells and screams of the enraged combatants, the gaunt old man, grim

and stern of countenance; and the other animals, all formed a horrid picture,

which did not seem real. While the row was at its height, and everything

pointed to the possibility of one of the combatants falling lifeless at

the feet of the other, a form glided through the darkness.

“At last,” said Val. “Look, Harry, isn’t she beautiful?”

This was a stretch of imagination on his part, as Dana’s features were

half hidden in a lace mantle, and could not therefore be judged of.Her

form was graceful, and almost statuesque in its shapely proportions.

“Yunacka, down, sir,” she said sharply. “Come here this instant.”

He turned at the sound of her voice, when the ape dealt him a blow on

the head which would have killed an ordinary mortal, but only doubly enraged

him. The next moment the combat was renewed with more fury than ever. Putting

forth all his strength, Yunacka dealt the ape a blow which felled it to

the earth. He was about to deal it a coup de grace when Dana’s voice arrested

him. So great was her influence over the wild creature that he threw himself

at her feet and licked her hand, like a faithful dog.

“Father,” she said to the old man, “what is the meaning of this? I thought

they were such good friends.”

“Alas! my daughter, see for yourself what brute passions lead to. They

quarrelled over some fruit. I’m afraid my poor friend is dying.”

“I hope not,” she replied.

Then turning to us, she said— “Give me a little water.”

Val snatched up a tin in a great hurry, and, as ill-luck would have

it, upset the contents. He looked awfully sheepish, and at once darted

off to refill it. I dashed after him, and Dana, snatching up her rifle,

followed. I did not anticipate danger, but she did, knowing that the denizens

of the jungle used the rivulet as a drinking place. Her eyesight was keener

than mine, for she espied a crouching beast, where I saw nothing. Bang!

bang! went both barrels to our great amazement, followed by an angry roar

from some brute in its mortal agony. A buffalo stood near us, drinking,

under the shade of a large tree.

Suddenly it bellowed, and we saw some huge body fold itself about it,

followed by the noise of cracking bones. The poor beast was in the deadly

embraces of a large boa-constrictor. I was glad to get away from the spot,

for the groans of the wretched buffalo made me feel sick at heart. On returning

to the bivouac the ape had partly recovered, and under Dana’s treatment

was quickly itself again, and followed the fakir, evidently pleased to

get out of Yunacka’s reach.

Dana stayed with us a short while, and was very jolly company.

“Don’t you think you had better go home?” she said. “You have had a

taste of jungle life. Be advised, and give up your intention of roaming

any further.”

“Oh, we’ll be all right when we meet Golob,” replied Val. “He is a shikaree,

and will pull us through everything; besides, it’s worth all the danger

to have met you, Miss Dana.”

She was radiantly beautiful, and reminded me of somebody I had before

seen, but whom I could not remember. She avoided all reference to herself,

or her mysterious sojourn in the heart of an Indian jungle, and after partaking

of some tea she bade us good night, and disappeared as mysteriously as

she had come.

CHAPTER IX

Harry and Val kept awake the remainder of the night, talking over what

had transpired.

“As for tigers,” said Val disdainfully, “I don’t think much of them;

they’re nobodies in my estimation.”

“Don’t run them down,” said Harry. “They seem very partial to you.”

“Don’t chaff, Harry. Mrs. Tiger treated me very fairly, certainly; but

Dana isn’t quite so chummy as she might be, you know.”

“Oh, you think she favours me.”

“Don’t be conceited, Barry. Didn’t she run after me when I went for

the water? and you can’t say she didn’t knock that tiger over just when

it was in the act of collaring me.”

“I was there, you know, Val.”

“Nonsense. I tell yon she likes me.”

“And me.”

“You are aggravating, Harry. Didn’t we toss up, and I won her?”

“I am not convinced, Val.”

“Then I’ll ask her who she likes best when I see her; but there’s daylight.

Look at the glorious rays of old Sol.”

The faint rosy tint of morn tipped the trees and bushes, and beautified

everything. Birds of brilliant plumage flitted about, making the place

vocal with sound, chanting their matins, and looking as if they enjoyed

their lives.Troops of monkeys gambolled among the trees, hailing the light

of the glorious sun as something to be thankful for. Squirrels frisked

about in search of food, and sat and ate roots and cracked woodnuts in

their pretty fashion. Even snakes came out of their holes to bask in the

warm rays, which chased away the dews of night, and painted the flowers,

which grew here in rich abundance.

“Isn’t this glorious, Val?” said Harry, baring his head to the zephyr-like

breeze.

“Very,” replied Val; “but I begin to feel peckish. Thanks to Yunacka,

we can have a venison steak for breakfast, I wonder where the fellow is?”

Hardly had he spoken than the wild boy dropped at their feet, having

slept in the branches overhead. Good morning, my friend,” said Val, raising

his cork helmet ceremoniously. “Talk of somebody, and he’s sure to appear.”

The wild creature laughed, and rubbed his hands as he held them over

the blazing embers, the warmth being evidently very pleasing to him.

“Yunacka, you’re to be scullery-maid. Attend to the fires.”

To show him Harry placed some sticks on the fire, and motioned to him

to do the same, which he did. Now that they had a good look at him in the

daylight, he was not so uncouth; there was something winning in his face,

despite his general appearance.

“Now, then, for breakfast,” said Harry, as he drew the ramrods, and

prepared to cook the meal. “Val, skin the deer and cut it up in readiness.”

Yunacka was like a parched pea in a frying-pan, looking at this and

that, and watching Val’s operations with evident satisfaction. The hunting-knife

was an object of curiosity to him.

“Here Yunacka,” said Val, passing him a steak, “give that to Harry.

Ha, you rascal! It isn’t fit to eat yet.”

Yunacka had given evident intentions of devouring the meat raw, but

desisted on being reproved. He saw the hunting-knife on the ground, and

picked it up, and began examining it, licking the blade first. They were

greatly amused at his operations, especially when he cut his finger. He

showed his teeth like a monkey, glared at the knife, and then threw it

into the fire.

“Halloa!” said Val, “don’t make so free with my property, or we’ll quarrel.”

He drew the knife out of the fire, and put it aside to cool. The tea

and sugar were placed in readiness for use. close to the trunk of the tree,

little dreaming that thieves were about in the shape of monkeys, who were

pilfering the sugar, when they were detected by Yunacka. Before he could

capture the offenders, they were up the tree, chattering, swearing, and

making faces. Val, annoyed by their chattering, picked up a stone and threw

it at them, to which they replied by pelting down wood apples. Yunacka

got a nasty crack on the head. Picking up the knife, he ascended the tree,

and then commenced prodding every unfortunate monkey he could get near.

Such a screaming and chattering were never heard than that now ensued.

Yunacka’s sardonic laugh accompanied every yell given by his victims. While

enjoying the fun, a procession of servants appeared, bearing a variety

of dishes, which emitted an appetising odour.

“Dana has thought of me,” said Val.

“I bet she has addressed a note to me, Val,” said Harry.

“We needn’t have cooked our own breakfast if we had known; but there,

I thought she wouldn’t forget me.”

Val was evidently smitten with Dana, and was working himself up into

a belief that she reciprocated his feelings. There was no note, only Miss

Dana’s compliments, which elicited a comical look of triumph from Val,

at which Harry laughed heartily. Yunacka’s olfactory organs were tickled

by the smell of the good things, and he quickly descended, with a grin

of satisfaction, at having chastised the monkeys for their daring impudence.

The breakfast commenced, and the wild boy, who tasted delicious coffee

for the first time in his life, enjoyed it. So much did he like it that

he suddenly seized the coffee-pot, and drank the hot stuff through the

spout, scalding his mouth, at which he spluttered, and made such grimaces

that his companions were fairly convulsed with laughter.

A dish of “kedgeric,” made of rice and lentils, pleased him immensely.

He held out his plate for more. Harry thought he had had enough, and refused,

which elicited from him a growl of dissatisfaction. Suddenly he seized

the dish, and bolted with it into the tree, where he sat, eating to his

heart’s content, not caring a whit for threats or coaxings.

CHAPTER X

The servants were anxious for the recovery of their mistress’s property,

in the shape of the silver dish, and one of them spoke harshly to the wild

boy, and then threw a stone at him. Yunacka hurled the empty dish at the

fellow, and struck him on the head, and he went down like a ninepin, but

was not much hurt.

Harry was angry at the boy’s conduct, and called him down sharply. When

he came, he caught up a stick and gave him several blows. He was penitent

enough after awhile. He was receiving his first lesson in discipline, and

didn’t seem to like it much; his wild nature rebelled at all restraint.

At this juncture a bear came shambling along, and Yunacka, with a cry of

rage, dashed out, club in hand, and attacked it. The others watched the

combat eagerly, and with anxiety, the bear being full grown, and a very

powerful brute. As usual it hugged Yunacka; who, however struck it with

his club, and the long nails of his left hand tore its breast open. The

combatants fell at last, when the wild boy managed to free himself, and,

before the bear could rise, dealt it several terrific blows with the club,

which stunned it. The battle was over, the victory complete, when Val rushed

in, and slew the animal with his hunting-knife.

After the things had been carried away by the servants, Val and Harry

dragged the carcase of the bear to their bivouac, and were about to skin

it when Dana appeared.

“That’s, a fine fellow. Did you shoot it?” she asked.

“Yunacka stunned it,” replied Harry.

“And I gave it the finishing stroke,” said Val, assuming an air of importance.

“But where is Yunacka?” she asked.

He had taken himself off somewhere to dress his wounds.

“Will you accept of the skin, miss?” asked Harry.

“It isn’t yours to give, it’s mine!” said Val, with an aggrieved air;

“but you can have it, Dana. Won’t it keep you warm at night, eh?”

“Boy,” said Dana, with a merry twinkle in her dark eyes, “don’t give

way to jealousy.”

“Me jealous — and of Harry? No. I’m sure you like me best, Dana; don’t

you?”

“Why should I like you?”

“Didn’t you save my life?”

“So she did mine,” said Harry, somewhat hotly, for he didn’t quite like

Val’s air of proprietorship.

“If you are going to quarrel about me,” she said, “I must say good morning.”

“I beg your pardon, Dana,” said Val. “It was stupid, of me. I’m so impulsive;

and I like you so much.”

“I apologise, too, miss,” said Harry; “and — and —”

“And you like me, too,” she said, with a laugh.

“Very much indeed. You saved my life.”

“Bosh! that’s stale news,” said Val. “Tell us something we don’t know.”

“Now, now, boys, don’t quarrel. Would you like to come and see my home?”

“It would afford us great pleasure, miss.”

“Call me Dana, please,” she said, “it sounds better out here in the

jungle.”

“And will you call me Harry?”

“Certainly; it’s a very pretty name, and a favourite of mine.”

Val felt fit to commit some absurdity or other, he was so wild at Dana’s

familiarity with his friend.

“Val isn’t at all a bad kind of name is it?” said Harry.

“You mind your own business, will you?” he growled.

“Come on, Val and Harry,” she said, with a laugh, “let’s have a race

home.”

Val’s face brightened when she mentioned his name.

“What shall we race for, Dana?” he asked.

“Home, of course.”

“Let’s make it for a kiss?”

“Val, don’t be rude!” said Harry, horrified at the proposal.

“I accept the bet, Val,” replied Dana. “Now then, a fair start. One,

two, three, and away!”

They started, Dana leading the way at a very fast pace.

CHAPTER XI

Dana won, being as fleet of foot as a young deer. They halted at a

gateway, hitherto hidden by the bamboo plantation, when Dana said— “You’ve

lost, you see.”

“Yes, but you’ve won. I’m ready to pay you, Dana,” said Val.

“But I don’t want paying.”

“Oh, come, that isn’t fair,” said Val. “You must be paid.”

“As second, you’ve saved your stakes, Val,” she said mischievously,

“Harry, you can pay me.”

Harry kissed her, and gave Val a look of triumph, and received one of

defiance if not hatred, in return.

“You may, if you like, Val,” she said demurely.

“I ought to have paid mine first,” he said; “but better late than never.”

He saluted her lips, and good humour was instantly restored.They looked

about them in wonder and amazement; here in the heart of an immense jungle,

surrounded by wild animals, and noxious reptiles, was a house and grounds

which could vie with any ever seen. The demesne covered several acres of

ground and was in beautiful order, and full of flowers and fruit of the

choicest kinds. The house, or rather bungalow, was on the ground, and contained

many lofty rooms, the whole surrounded by a verandah, to keep off the sun,

and to afford a cool seat for the inmates.

“Isn’t this jolly?” said Val, putting his hands in his pockets, and

looking round with the air of a lord, “I could stay here always, Dana.”

“You’re not a man, yet,” she said, laughing.

“I wish I was,” said Val.

“Why?” she asked.

“Because then I’d marry you.”

“Oh, indeed,” was the laughing reply. But suppose I didn’t care for

you enough, eh?”

This was a floorer, from which Val took some time to recover. Not care

for him — impossible! The idea was monstrous to him — too ridiculous to

be entertained.

“Besides,” said Harry, somewhat spitefully, “there’s money wanted, Val.”

“Go it, pile on the agony! and all just because a fellow is honest enough

to speak the truth. I mean to marry Dana, or not at all.”

“Don’t talk nonsense, Val,” she said, smiling. “Let us eat some fruit.”

They were soon busily engaged in picking delicious fruits, and eating

them in this veritable paradise. The sun was shining brightly, the trees

full of birds, and a gentle breeze was blowing, making music to the melody

of a miniature waterfall. Suddenly a large cobra emerged from a rhododendron

bush, and reared itself just in front of Dana. Harry seized a stick to

strike it down, when she said —

“Don’t, Harry, it’s one of my pets. See, it only wants to greet me.”

She stroked its head gently, when it displayed every mark of delight.

Its forked tongue moved like a magnetic needle, and its body swayed

to and fro with a graceful, undulating motion.

“It follows me about like a dog,” she said.

“Come along, Baboo, and have some milk, my pet.”

The snake glided along by her side, but hissed when the others went

too near it. She put a saucer of milk and sugar down, from which it fed,

while Val and Harry looked on with wonder. Both hated snakes, and invariably

killed any they fell across, yet here was one quite tame, and displaying

an affection and docility that was amazing.

“Are you afraid of snakes?” she asked.

“Yes, very,” replied Harry.

“I’m not,” said Val. “See, I’ll take Baboo up.”

Dana pulled him sharply back, saying — “Don’t touch it, for your life.

A bite would produce almost instant death.”

“And yet you handle it?” he said incredulously.

“Yes; I found it when it was quite a baby, almost dead. I fed and nursed

it, until it has grown into the fine fellow it now is; but I have wonderful

power over snakes. Come, I’ll show you what I mean.”

She led the way to the extreme end of the grounds, where there was a

regular menagerie of animals and snakes.

“You see that fellow,” she said, pointing out a huge cobra, which struck

at the wire netting viciously, “it’s of a species called cannibal, because

it eats its fellow snakes, and is perfectly untameable.”

“You’re’ not going to handle that fellow, surely?” said Val.

“Yes, I certainly am.”

“Don’t, Dana; think of the danger.”

Harry joined his entreaties to his, but she only laughed, displaying

a set of teeth that vied with pearls in appearance.

“Stand aside, just out of sight of the creature,” she said. “The sight

of you irritates it; and mark what follows.”

They did as she desired, and saw a wonderful sight. The snake stood

perfectly erect, being four feet and more in length, eyeing Dana, who remained

motionless, its hood expanded, a sure sign of its being in a state of rage.

Like the rattlesnake, which never strikes until it has sounded its rattle,

the cobra never bites while its hood is flat. Dana fixed her eyes on the

reptile, which vainly endeavoured to evade them, hissing and showing signs

of fear now, as if it knew it was about to pass under a spell. At first

it swayed its body to and fro, almost violently, then this ceased gradually,

and it stood perfectly rigid, as if suddenly turned to stone.

CHAPTER XII

Meanwhile another person, who is to exercise an influence upon the

lives of the personages of this story, was unconsciously approaching. He

was a stranger, out on a botanising expedition, having come from Lucknow,

where he was attached to the court of the King of Oude. He was quite a

youth, being only eighteen, and had only recently arrived from England.

He was handsome, clever, and a charming fellow, and his name, Clarence

Fitzhugh. He knew no fear as he traversed these wilds, pack on back, in

which he kept his specimens, for he was a decent shot.

“Halloa!” he said, on seeing the smouldering embers of the bivouac fires,

and the guns, and personal belongings of the boys; “somebody’s about. I

wonder who?”

He took up the rifle and examined it, when Yunacka, bristling with rage,

dropped from the tree, club in hand, and confronted him. The wild boy seemed

to have some indistinct notion regarding the rights of property, and that

the stranger had no business to meddle with the rifles of his friends.

“Bless me, what a wonderful-looking creature this is,” Clarence thought.

“Half monkey, half man, I should say. What does he want, I wonder?”

Yunacka jabbered like a monkey, and was evidently about to attack him,

when the young man quickly raised the rifle and fired, thinking it would

bring the owner of the weapons to the spot.

The young man quickly raised the rifle and fired.

As before, Yunacka, on hearing the report, tumbled head over heels,

and rolled over and over like a ball.

“That fellow would make his fortune in a circus,” thought Clarence,

as he watched the queer antics of the wild creature.

“I wonder who and what he is? I wonder, too, if the owner of this carcase

would mind my having a venison steak? I feel precious hungry. Here goes;

I’ll eat first, and ask permission afterwards.”

He soon had a brisk fire, and proceeded to cook his luncheon, using

the carcase of the bear as a seat. Having got over his fright, Yunacka

shambled back, looking penitent, and inclined to make friends with the

man who could make thunder at a moment’s notice.

“Well, my funny friend,” said Clarence, laughing and holding out his

hand, “Won’t you shake hands, eh?”

Yunacka took his hand and looked at it, but did not attempt to shake

it; in fact, he seemed at a loss to understand what was required of him.

“That’s how it’s done,” said Clarence, squeezing the hairy boy’s hand,

and nodding good-humouredly.

Yunacka’s closed on his with a grip like iron, making him wince, as

he said — “Hi! that’s enough. Come, come; I don’t want to shake hands any

longer.”

The wild creature grinned, and pressed harder, bringing the tears into

his companion’s eyes.

“I’ll give you a smack aside the head, if you don’t let go,” said Clarence,

at last. “There, how do you like that?”

Yunacka staggered under the blow, and released his hold. He did not

resent it, but knelt at Clarence’s feet to show him he submitted.

“I was a brute to hit you; you knew no better,” said Clarence, patting

him on the head. “Poor creature; come and have something to eat.”

Yunacka was pleased to find himself received into favour, and began

stoking the fire, casting a longing eye at the steaks, which were cooking.

Clarence lit a cigar, and commenced smoking, greatly to the wild boy’s

astonishment, who looked at the lighted cigar, and the smoke, with curiosity

mixed with fear.

Perceiving this, Clarence good-naturedly lit another cigar, and handed

it to him, saying — “Try a weed, old man.”

Yunacka squatted like a monkey, and then looked at the cigar, popping

the wrong end into his mouth and getting burnt.

“No, stupid, not that way. Let me show you,” said Clarence, laughing,

and

putting the right end into Yunacka’s mouth.

He soon took to it, and smoked away furiously, watching the smoke curling

above his nose with great glee.

“I wonder whether it will make the odd creature sick?” he thought. “This

is an adventure if you like. Now for luncheon. Come, old man; everything

is ready.”

He gave the wild boy a large piece of meat, which he devoured hot, and

with evident relish.

“What an appetite the creature has,” thought Clarence. “There, there’s

more. Eat away; it’s a real pleasure to watch you.”

Yunacka darted away when his appetite was satisfied, and climbing a

cocoa-nut tree, brought down some nuts, and gave them to Clarence. He also

brought guavas, mangoes, bananas, and other fruits, and Clarence enjoyed

the best luncheon he had had for several days.

CHAPTER XIII

Meanwhile Val and Harry watched with the greatest interest the struggle

for mastery between Dana and the snake. The cobra gradually sank to the

bottom of the cage, and lay perfectly motionless.

“You can come now,” she said, as she opened the door, and entering,

lifted the snake which was as stiff and rigid as a log of wood.

They could not help observing the peculiar expression of her face more

particularly of her eyes, which blazed like fire. She was a wonderful creature,

and they almost began to be afraid of her.

“What manner of girl is this,” they thought, “who can reduce a venomous

untameable creature like this to slavery?”

“By Jove, Dana, you’re a plucky girl. I think you could send me to sleep

too, if you cared to try,” said Val.

“I can mesmerise you,” she said, laughing; “shall I try? If I do you

are bound to tell me all your secrets.”

They handled the snake with impunity, and examined the marks on the

head, which were exactly like a pair of spectacles.

“I say,” said Val, “I have an idea that you I and Dana could stump the

country as itinerant show people; we’d make lots of coin.”

“Not a bad idea, certainly,” said Dana, laughing. “But I don’t think

we’ll take up with it just now, at least. Come and see my other pets.”

A large tigress, a splendid creature, bounded from side to side of its

cage when it saw her. It had thee cubs, the size of poodle dogs, and they

also were evidently pleased to see their mistress.

“All my pets,” she said, “have been reared from mere babies. I shall

go in to see ’Pussy’ and her little ones. Would you like to come too, Val?”

“Certainly,” he said. “I’m not afraid of tigers. I’ll undertake to kill

any amount of them.”

Dana opened the door of the cage, and went in followed by Val, with

the air of a gladiator going to deadly combat.

“Pussy,” as the tigress was called, purred like a cat, and rubbed its

glossy coat against her mistress, who caressed her.

The cubs too frisked about, and one of them rushed through Val’s legs,

upsetting him. Val got up in a rage, and kicked the cub, which howled with

pain.

“Get out for your life,” said Dana in a harsh voice, “quick!”

But Val wouldn’t, although the tigress glared at him, and tried to pass

Dana, who, however, kept her position.

“For Heaven’s sake, Val, come out!” cried Harry. “Don’t you see Dana’s

danger as well as your own?”

“Nonsense!” he said. “I’m not afraid of her.”

The tigress growled, and rearing, placed its paws on Dana’s shoulders,

showing its horrid fangs.

“Val, go! go!” she said in a faint voice. “I can’t stand this pressure

much longer. Oh, Heavens, why don’t you go?”

Harry rushed in, dragged him out, and shut the door of the cage, only

just in time, for Dana fell, and the tigress bounded over her prostrate

form.

“Run for assistance to the house,” cried Harry. “Quick, or it will be

too late.”

Val was serious enough now; all the bravado had been taken out of him

by Dana’s danger, and he ran off at the top of his speed.

“Dana,” said Harry, as he pushed his handkerchief through the bars,

“cover your left shoulder with this; it’s bleeding.”

“Thanks,” she said. “I’ll lie perfectly still, and perhaps she will

get pacified.”

“Can I do nothing?”

“Yes. Leave the door slightly ajar when you get a chance. I can work

my way gradually there, and get through perhaps.”

Watching his opportunity he did this, while she talked to the tigress,

calling it her “dear Pussy,” and fondling the cubs, which raced over her

in their gambols.

“Val has gone for assistance. Shall we shoot the tigress?” asked Harry.

“No, no; a red-hot iron will be the best. I’m afraid I’ve lost all control

over her for the present.”

Dana cautiously worked her way to the door of the cage, on her back

and the tigress bounded from side to side, lashing its tail, and growling

fiercely.

CHAPTER XIV

Meanwhile Clarence Fitzhugh had finished his meal, and wondered why

it was the owners of the guns, etc., did not return.

“They can’t have fallen victims to wild beasts,” he thought, “or been

murdered by the Thugs?”

He had heard and read of the existence of these wretches, who, under

the guise of religion, entrap and murder unsuspecting travellers. It suddenly

struck Clarence that Yunacka might throw some light on the subject, and

a horrible suspicion crossed him that the wild creature might have destroyed

them in their sleep. However, he put the thought away from him, as being

too dreadful, and taking up one of the guns pointed to it, and then by