Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages in Archive

Volume 8075

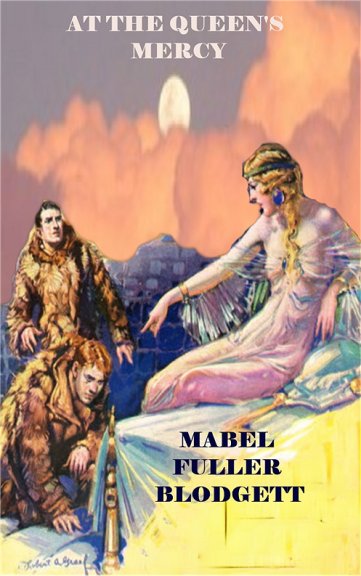

AT THE QUEENS MERCY (1897)

by Mabel Fuller Blodgett

In 1897, Lamson, Wolfe and Company of

Boston, New York, and London published a new adventure novel of darkest Africa,

AT THE QUEEN’S MERCY, written by a nineteen-year-old bride, Mabel Fuller

Blodgett. It inncluded five interior illustrations by Henry Sadham Novels such as this were best known to be the

providence of Sir Henry Rider Haggard, and truth be told, there are some

similarities to SHE to be found in Mabel’s tale. As yet, American writers

hadn’t jumped on the ‘African Adventure’ genre bandwagon. That was a charge

that would be led by Edgar Rice Burroughs more than a decade later.

She was born on April 10, 1869, as Mabel Louise

Fuller in Bangor, Maine, the daughter of Ransom Burritt

Fuller and Louise White. Her father became the president of two insurance

companies in Boston. She graduated from the Sacred Heart Convent at Elmhurst

in Providence,

Rhode Island. Her subsequent works include:

She also published a non-fiction

work, The Life and Letters of Richard Ashley Blodgett, First Lieutenant

United States Air Service in 1919. Richard Blodgett was her son, and he

was killed in action during World War I.

Blodgett was living with her husband,

attorney Edward E. Blodgett, in Brookline, Massachusetts by 1897,

when Richard was born. She is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

There’s absolutely no evidence that Mabel

read SHE or even a single ALLAN QUATERMAIN novel, but there are some

similarities. There’s no evidence that Edgar Rice Burroughs read AT THE QUEEN’S

MERCY, but there are some similarities. A PDF of her novel accompanies this

brief article. Read it and make your own determination.

In any event, Mabel finished school and was

promptly married to Edward Blodgett, who worked diligently as an attorney. She

could have stayed home and done chores, but her family had been very well off

and her husband was quite successful, and she wasn’t born to be a housewife.

Television and even radio weren’t even imagined, so that left books. Probably,

not unlike Edgar Rice Burroughs a few years later, she read something and

thought, I can write stuff this bad. So, she sat down, put pen to paper,

or paper in a typewriter, and wrote, I am a plain man, and to do a plain

man’s work was every more to my taste than to set down with a clerk’s skill

such happenings as have befallen. It’s not Call me Ishmel or It

was the best of times, it was the worst of times; but it’s not that bad. I've written worse myself.

About

46,000 words later, she wrote, Out of all the world we two stand apart. For

life, for death; for good, for ill; for joy, for sorrow, thou and I, together

and alone.” She

smiled to herself, edited it a few times, and perhaps

called on her husband to have a clerk at the law office retype. She

bundled the manuscript and sent it to a publisher and they bought it.

In those days,

manuscripts, hard copies because that’s all there were, were mailed or

couriered to publishers, one after another. It was customary to send

them with

postage prepaid for the return of the manuscript – because there was

only one.

She

sold the story immediately, not to a magazine but to the publisher, who was

probably a fan of H. Rider Haggard and thought it was about time an American

wrote "one of those stories." There’s no record of what she was paid.

Now

for the story. It is frequently confused with “At the Mercy of the Queen” by

Anne Clinard Barnhill, a tale of court intrigue during the reign of Henry VIII.

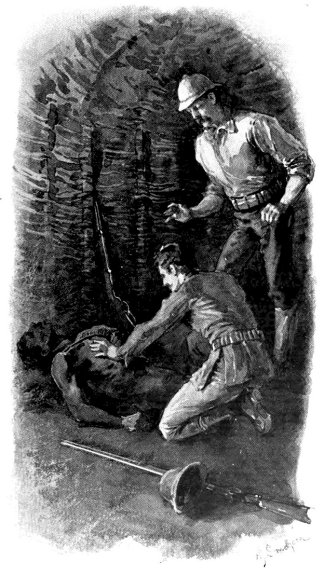

This is a tale of adventure, of two men, John Dering and Gaston Lestrade.

The

story is told from the first-person perspective of John Dering. In the first

chapter, we learn that Gaston is a handsome womanizer and that the two are in

Africa. An injured man is chased into their camp. The Europeans repel his

pursuers. He’s dying and requests that they bury him and promises to tell them

of his city, his Queen named Lah, and of hidden treasure.

The

dying man, Sagamoso, tells them that he fled the city because had fallen in

love, forbidden love, with one of the Queen’s maidens. He begged for burial and

the rescue of his love, and then he told them how to find the treasure. Gaston

was never a man to quail in the pursuit of beauty and Dering was found of gold,

so the die was cast.

I’m

not going to tell you the story. It’s right here. Read it for yourself. https://www.ERBzine.com/mag80/at the queen's mercy.pdf

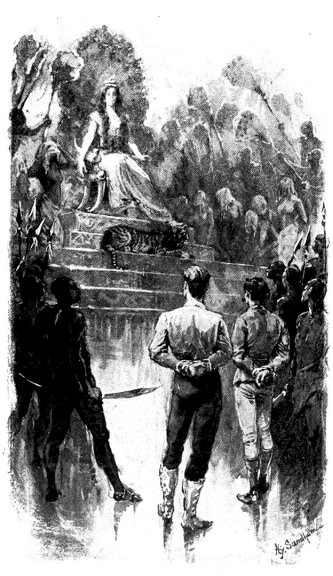

Suffice

to say that the citizens of the ‘walled city’ find our adventurers and capture

them. The two had killed a gorilla in the jungle and Agno, the high priest,

demanded their death for killing the sacred ape. Lah, the queen, was smitten by

Lestrade, but she couldn’t refuse to punish the men, but she demanded the right

to determine the time and manner of their death, a death postponed, but not

reprieved.

That’s

all I’m going to tell you, but consider. A hidden city in the jungle, one with

a beautiful white queen named Lah. She falls in love with Gaston Lestrade, a

handsome outsider, and risks her throne for his love. The people, follow the

priest, Agno, who desires the Queen for himself, and insists that the outsiders

be executed. Meanwhile, our adventures both want the gold, and unlike Tarzan,

in books to be written by another far better-known author years later, Gaston

wouldn’t mind having the Queen, as well.

If

you want a printed copy of the book and don’t want to spring for a first

edition, it’s available in paperback for less that $10.00 from Lulu. Just enter

“At the Queen’s Mercy,” in the search bar and pick the one with two men

kneeling in front of a barbarian queen. If you don’t want to buy it, open the

PDF attached.

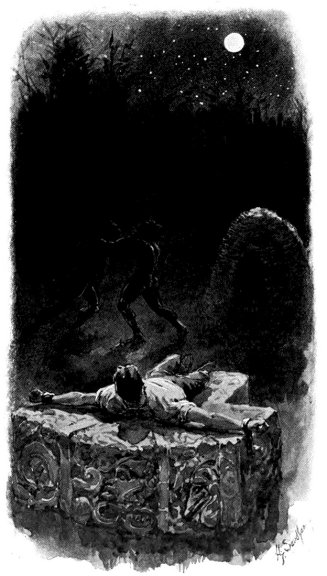

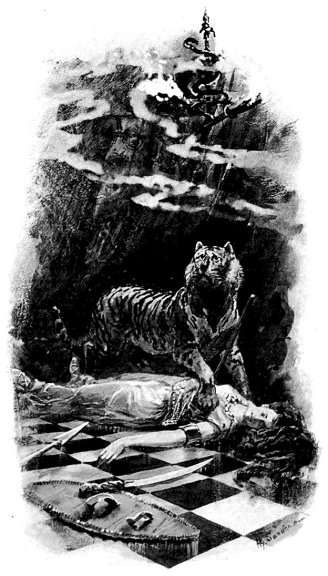

A SAMPLE GALLERY OF THE BOOK'S ILLUSTRATIONS

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2025 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.