Volume 1836

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/jungleboy.htm

| Chapter I. | Prince Nasrullah Khan -- At Wargrave Hall -- The Family Skeleton. |

| Chapter II. | Sexton Blake's Vigil -- The Cord of Thuggee -- Lord Wargrave Explains. |

| Chapter III. | An Abrupt Dismissal -- A Telegram -- The Murder at West Kensington. |

| Chapter IV. | Sexton Blake's Discovery -- A Conspiracy of Silence. |

| Chapter V. | At Baker Street -- Chester Carton's Story -- Sexton Blake's Commission. |

| Chapter VI. | A Futile Fortnight -- The Coming of Govind -- The Man in the Bushes. |

| Chapter VII. | The Dak-Bungalow -- The Shots from the Window -- On to Narpur. |

| Chapter VIII. | The Jungle Village -- The Zemindar's Queer Tale -- The Night Alarm. |

| Chapter IX. | The Way to Talnagore -- The Wizard of the Jungle -- The Fiendishness of Amar Singh. |

| Chapter X. | Jammu's Confession -- The Passing Elephant -- A Summons to the Palace. |

| Chapter XI. | The Flag of Britain -- The Hope that Failed. |

| Chapter XII. | The Interview with the Nawab --Trapped -- Bala Sahib's Temptation. |

| Chapter XIII. | The Truth Revealed -- A Fortunate Visit -- The Escape from the Palace. |

| Chapter XIV. | The Secret of the Desk -- A Strange Alarm -- Off to the Jungle. |

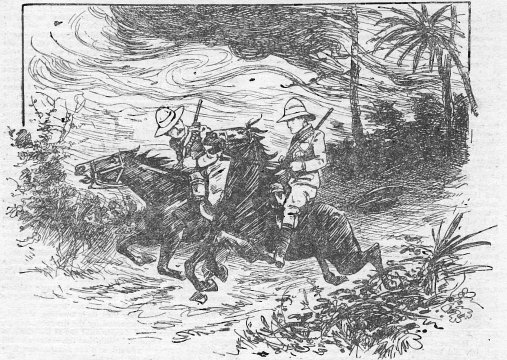

| Chapter XV. | The Coming of Amar Singh -- Murder Foiled -- The Fight with the Sowars. |

| Chapter XVI. | Bala Sahib is Convinced -- The Attack -- The Fight with the Panthers -- Carnac Sahib. |

| Chapter XVII. | The Ride to Talnagore -- The Burning Palace -- The End of the Nawab. |

| Chapter XVIII. | Home Again! -- Chester Carton's Greeting -- Retribution. |

"It will make a fine newspaper story," said Chester Carton, putting his notebook into his pocket, "and I am sure to get five or six guineas for it, which is a sum not to be despised. Such a windfall does not often come my way."

"Nor am I often tempted to speak so freely. But your fine old Burgundy, Carton, seems to have loosed my tongue."

It was between eight and nine o'clock of a February night, in the year 1904, and the scene was Martinetti's well-known restaurant in the Haymarket. Waiters moved to and from between exotic plants in pots, bearing covered dishes. Corks were popping, and gold-necked bottles tinkled in ice-pails. At the little tables, with their crimson-shaded electric lamps, sat groups of well-dressed people, many of them foreigners, laughing and chatting as they ate, drank and smoked. The detective had been dining here with his friend by appointment, and the two had reached the coffee and liqueur stage. Chester Carton, author and journalist, was a man who looked as if he might be anywhere between forty and fifty, a tall, slim man, with perfectly shaped hands, tawny moustache and pointed beard, brown eyes, and features that were always grave and sad, as if he found the burden of life a heavy one. Sexton Blake had first made his acquaintance several years before.

"Are you very busy?" inquired the detective.

"Much as usual," was the reply. "And you?"

"I have no work at present. For a month or so, my dear fellow, I hope to enjoy luxurious ease."

"You won't," declared Carton. "In a few days, I'll wager, you will be in harness again, delving into some deep mystery. Crime never ceases; wickedness is ever active. Even as we sit here, perhaps, Fate is spinning a tangled web for you to --"

There was an abrupt pause. A man, who had been dining in an adjoining room, was passing down the main restaurant, and Chester Carton was staring at him breathlessly with parted lips. The stranger wore ill-fitting European clothes, and carried on his arm a tweed overcoat and an ivory-mounted stick; but his turban of spotless white, his dark complexion, and black beard --- split in the middle --- proclaimed him unmistakably to be a native of India --- a Hindoo or a Mohammedan. He went on, glancing neither to right nor left, and the street door closed behind him.

"What's the matter?" exclaimed Sexton Blake. "You look as if you had seen a ghost."

"I have," muttered the journalist. "Yes, a ghost from the past!" He was on his feet, his face flushed and excited, pressing a hand to his brow. "Waiter!" he added. "That man who just left, who is he? Do you know anything about him?"

"Very little, sir," was the reply. "He calls himself Prince Nasrulla Khan, and this is the third evening he has dined here."

"Nasrulla Khan?" echoed Chester Carton. "I hope you won't mind my rushing off, Blake; professional zeal, you know. I want to interview this prince. I'll drop you a line to-morrow!"

And with that, seizing his hat and coat, he made a hasty exit.

"Queer," reflected Sexton Blake, as he lit another cigarette and watched the curling smoke. "I wouldn't mind betting that there is more than an interview in the wind. Come to think of it, Carton spent some years in India, from what he told me."

The detective was interested, and when he returned to his chambers in Baker Street that night the scene he had witnessed in Martinetti's restaurant was still in his mind. Before going to bed, he ran through a little book that was to India what Burke and Devrett are to Great Britain, but he failed to find the name or title of Nasrulla Khan.

The sun was shining, and the table was temptingly laid for breakfast, when Sexton Blake emerged from his dressing room fresh and ruddy after a cold tub.

"Any letters, Tinker?" he inquired of the lad who lived with him as a sort of adopted son, and was useful to him in many ways.

"Yes sir; five letters and a telegram," was the reply.

"Any news in the papers?"

"Nothing in your line, sir."

Sexton Blake opened the letters between bites of toast and sips of tea, and put four aside that were of no importance. The fifth was a brief scrawl from Chester Carton, saying that he would probably call at Baker Street that evening, and the telegram, which the detective read aloud, ran as follows:

"Wargrave Hall, Berks.

"Lord Wargrave presents his compliments to Mr. Sexton Blake, and begs that he come down as soon as possible to investigate a case of burglary."

"The papers don't mention it," said Tinker.

"No, they couldn't have heard of it yet," replied the detective. "This puts an end to my intended holiday," he added. "You can pack a small bag for me, my boy. I shall go as an expected guest."

"Do you know Lord Walgrave?"

"I have never seen him to the best of my knowledge, but I hope to make his acquaintance very soon. By the by, Tinker, drop Mr. Carton a line -- you know his address in Chancery Lane -- and tell him that I have been called out of town for a day or two."

The journalist's prophecy had already come true, and the crested missive from an English noble man was to lead to amazing and perilous adventures. But little did Sexton Blake imagine what the future held in store for him, little did he dream of the links that Fate was forging for himself and Chester Carton, for Lord Wargrave and Prince Nasrulla Khan, as he consulted a Bradshaw and made brief preparations for the journey.

Attired in stylish morning-dress, looking like a gentleman of leisure, he took a cab to Paddington and travelled down to a station not a great distance beyond Henley. Here a closed carriage was waiting for him --- he had sent a wire from Baker Street before he left --- and a drive of three miles along the pretty Berkshire roads to the village of Hertsey, and a quarter of a mile beyond, brought him to the lodge gates of the Wargrave estate, where a pair of griffins squatted on their granite pedestals.

Another half mile, through wooded grounds, and the house was reached. It was an ancient, ivy-covered mansion of three storeys, and from the front two wings abutted right and left, forming a three-sided court. To Sexton Blake's surprise a Hindoo servant appeared --- a middle-aged, clean-shaven man in white linen and turban. He opened the carriage and took the bag from the detective, who, a moment later, stood in a luxuriously furnished library, in the presence of Lord Wargrave. The latter was a tall and handsome man, looking under forty, with a bronzed complexion and a heavy brown moustache.

"I see you have a Hindoo servant, my lord," was Sexton Blake's first remark.

"Yes; Amar Singh," said Lord Wargrave. "He was in my service in India years ago, when I held a civil position at Madras, and I brought him to England after I succeeded my father. I am obliged to you for coming so promptly, Mr. Blake," he went on, lowering his voice. "A burglary was committed here last night, and I wired to you on the impulse of the moment. From your point of view, however, it may be too trivial a case for you to undertake."

"I am at your lordship's service."

"Thank you. The facts are simply these. One or more daring thieves entered the house by a French window, broke into the butler's pantry, and went off with a service of silver plate. The discovery was made by the cook when she came downstairs early this morning. The butler heard nothing, though he slept on the ground floor; and that is easily accounted for, since he admits that he accepted a glass of ale from a stranger at the Blue Lion in the village between ten and eleven o'clock last night. I have no doubt that the drink was drugged,"

The detective nodded assent.

"You don't suspect any of the servants of complicity?" he inquired.

"No, we can leave them out of the question. The plate is of no great value, but I prize it highly because it has been in the family for generations."

"I will do my best to recover it for you, and I think I shall begin by searching for a clue in the neighbourhood."

"Very well," said Lord Wargrave. "For the present, then, you will remain here ostensibly as my guest. And now let us go to lunch."

The case was, indeed, of a commonplace nature, and better suited to an ordinary detective. But Sexton Blake had promised his assistance, and he set to work as earnestly as if he had the biggest kind of a mystery to solve. After lunch he put on a tweed suit, questioned the butler and the cook, carefully examined the grounds in the neighbourhood of the hall, and then walked into the village, where he made inquiries at the Blue Lion Inn, and other places.

It was dark when he returned, entering the house unseen by a side door, and passing on to the smoking- room, which as yet was not lighted. He had been sitting here for a few moments, disappointed by the failure of his quest, when he heard footsteps in the adjoining library, and then something else that checked his quick impulse to reveal his presence.

"By heavens, I am getting tired of this!" muttered a familiar voice. "I feel that I can endure it no longer! Yet I am helpless in the power of a rapacious scoundrel! And as long as the boy lives --"

The rest of the sentence was inaudible. Sexton Blake rose noiselessly, and two steps brought him to where he could see through the curtained doorway. Lord Wargarve had thrown himself into a padded chair in the library, with an envelope in one hand and a letter in the other. The firelight played on his face, which wore a haggard expression of anxiety and anger. Tearing envelope and letter into fragments, he rose and threw them into the fire, watching until they had faded to ashes. Then he left the room, closing the door behind him.

A moment later, Sexton Blake was in the library, his eyes scanning the floor, and by the edge of the grate he found a small fragment of the destroyed envelope. Having seen that it bore part of an Indian stamp, but no trace of a postmark, he put it into his pocket. Then he beat a retreat, back through the smoking-room, and slipped upstairs to his own chamber, where his evening clothes were laid out.

"The old story!" he told himself. "The family skeleton! Lord Wargrave is being blackmailed by somebody in India. A native marriage perhaps, and he daren't acknowledge the child in India. It is not a case in which I could be of any service, nor is it likely to offer me his confidence.

"That you have accomplished nothing so far is no disappointment to me," said Lord Wargrave, "for I did not expect you to succeed in so short a time. I am afraid you will have to look for the thieves in London. They are evidently experienced cracksmen."

"I think so," replied Sexton Blake. "Yes, I shall have to search for a clue in town. But I wish to remain here for another day, in order to make a more complete examination of the grounds, and to continue my inquiries in the village. Meanwhile, my lord, your silver is quite safe if it belongs to the Queen Anne period."

"It does," said Lord Wargrave. "I follow your meaning. The plate is worth ten times more intact than melted down, and the thieves are likely to keep it as it is until they can --"

He suddenly paused. The door had opened, and Amar Singh entered the room. His brown face was a shade paler and there was a worried look in his eyes. He stepped over to his master, stooped down, and whispered a few words in this ear. Lord Wargrave turned white to the lips, but instantly recovered his self-control.

"My steward," he said calmly, as he rose. "He has come with some poaching complaint, no doubt. Tell him that I will see him, Amar Singh. Will you excuse me, Mr. Blake?"

"Certainly," replied the detective, "I feel rather tired, so I shall go to bed." And he departed at once, leaving the two alone.

The smoking-room was at the rear of the house, and Sexton Blake did not get a glimpse of the visitor as he passed along the hall and ascended the staircase. He entered his bed-chamber and closed the door, but he had no intention whatever of retiring for the night. His professional instinct had been roused, and that was sufficient excuse for what would have been gross impertinence in an ordinary guest.

"It is not the steward," he reflected. "It is someone who is dreaded by both Lord Wargrave and Amar Singh, and I am anxious to have a peep at the man, whoever he may be."

The room was in the left wing, opening on the court, and one of the three windows that, towards the angle of the wall, commanded the nearest view of the entrance to the house. It was a clear and frosty night, and the moon was shining brightly on the old grey stonework and the tangle of ivy. Himself in darkness -- he had not turned on the light -- Sexton Blake posted himself behind the window- curtain.

It was a long a tiresome vigil. For more than an hour he waited and watched, until he was numbed with cold, and then his patience was rewarded. He had looked up for a moment, and when he lowered his gaze, he saw Lord Wargrave's visitor standing outside the front door, which had already been shut behind him. The man wore dark clothing and a tweed cap, and the next instant, as he stepped forward, the moonlight shone on his brown skin and split beard -- revealing to the amazed detective the features of Prince Nasrulla Khan, whom he had seen on the previous night in Martinetti's restaurant in the Haymarket.

"By Jove! This is getting interesting!" muttered Sexton Blake. "No doubt Nasrulla Khan is the blackmailer! He must have written from India to announce his coming, and arrived in England before the letter. But that don't fit in, unless Lord Wargrave received the letter several days ago. At all events, this unwelcome visitor was not expected at the Hall to-night, so much is certain."

The Hindoo walked rapidly away, without looking back, until he vanished from sight around the curve of the gravelled drive. And not three seconds later, as the detective was still at his post, a white-robed form slipped into view from behind the opposite wing of the house. It was Amar Singh, and something glittered at his waist. He glided on like a cat, following the edge of the drive until he came to the turn, and then he swerved aside and crept into the shrubbery.

"By heavens, I know what that means!" Sexton Blake told himself. "There will be murder done unless I can prevent it!"

He did not hesitate an instant. Noiselessly hoisting the window-casement, he swung over the sill, gripped the ivy with hands and feet, and lowered himself by the tough roots. He safely reached the ground, sped across the court, and was soon in the deep shadow of the trees and bushes. He hastened on as fast as he dared, keeping parallel with the drive, and had gone for a hundred yards when he heard a gurgling cry and the sound of a fall at no great distance ahead.

"Too late!" he thought. "The deed is done!"

But with that came the noise of a scuffle. Quickening his steps to a run, and the next instant bursting into a moonlit glade, he saw two men struggling in the frosted grass. Amar Singh was underneath, however, and his assailant was kneeling on top of him, holding him down with one hand and apparently pulling at something with the other. The truth immediately occurred to the detective. He understood the fiendish act.

"Enough of that, you scoundrel!" he cried.

Prince Nasrulla Khan sprang to his feet with a yell of surprise and terror, and bounded away like a deer, tearing through the thickets of evergreen timber. Sexton Blake had levelled a pistol, but he did not fire. He lowered the weapon, and then turned his attention to Amar Singh, who was writhing feebly on the ground, and uttering stifled, inarticulate sounds. And little wonder, for drawn tightly about his neck was a slender, silken cord, on which the would-be assassin had been pulling. The detective removed the noose, and after a brief struggle for breath --- he had been nearly suffocated --- the Hindoo was able to rise and speak.

"That was a close call for you, my friend." Said Sexton Blake.

"Very close, sahib," replied Amar Singh. "I should shortly have been dead. Where is my enemy?"

"The scoundrel fled in that direction. Come, we had better try to catch him!"

"It is useless. He is as cunning as a serpent. We should never find him in these deep woods."

Sexton Blake realised that this was true, and knew also that Amar Singh did not want the man to be caught. He picked up the rope and examined it intently. He was closely watched by the Hindoo, who had not uttered a word of gratitude to the rescuer.

"Ah, I thought so!" exclaimed Sexton Blake. "I cannot be mistaken! I have been in India, where this came from. It is a cord of Thuggee, used by that murderous brotherhood for strangling their victims; and the man who tried to take your life, Amar Singh, was himself a Thug."

"The sahib may be right. How should I know?"

"I don't say that you do," the detective answered cautiously. "But I am naturally puzzled by this incident. How did the fellow come to trap you?"

"When I open my lips," the Hindoo replied, "it will be in the presence of my master. Shall we go to him, sahib?"

"Yes I am ready. There is nothing to be done here."

No more was said. The two silently retraced their steps, following the drive, and on the way Sexton Blake mentally reconstructed the affair in the wood. To do so was easy. While stealthily seeking to overtake Lord Wargrave's visitor, with murderous intent, Amar Singh has either been heard, or else Prince Nasrulla Khan had suspected danger when he left, and guarded against it by lying in wait for the Hindoo and throwing the deadly noose over his head from behind.

"A true Thug, undoubtedly!" vowed the detective. "I wonder what will come of this?"

Lord Wargarve must have heard the cry, for he was standing outside the Hall, and the moonlight showed his startled and worried expression. A glance at Sexton Blake seemed to disconcert him still more. Without a word, he led the way to the smoking-room and closed the door.

"What does this mean?" he asked coldly. "Speak Amar Singh! You followed my instructions?"

"I did as you told me, my lord," replied the Hindoo, "and it is not my fault that I failed. I would have kept at a distance from your visitor, but he must have heard my footsteps, for he hid himself behind a tree, and as I passed he threw a rope over my head and drew it tight. I was about to be strangled when this sahib came to my rescue and frightened the assassin off."

"Well done, Mr. Blake!" said Lord Wargrave, eyeing the detective narrowly. "I am indeed grateful to you, for I value Amar Singh's life highly. You shall have a full explanation, but first ---"

"My own explanation, of course," broke in Sexton Blake. "It is perfectly simple. I no longer felt sleepy when I went upstairs, so I lit a cigar and sat for an hour or more thinking about the burglary. Then, as I was about to go to bed, I fancied I heard a footstep outside. I looked from the window, and saw a man on the drive, and a moment later, when he had disappeared, I saw your servant creeping in the same direction. Believing that a burglar had been prowling about, and that the Hindoo had discovered him, I hastily lowered myself to the ground by the ivy, ran across the park and reached the spot in time to prevent a tragedy. Here is the rope."

Convinced that the detective's story was true, Lord Wargrave's expression of relief was obvious. He took the silken cord, glanced at it carelessly, and threw it on the table.

"I deceived you when I told you that my visitor was the steward," he said, "but you will pardon me when you have heard the circumstances. Briefly, they are these.

"Years ago, when I was in India, the neighbourhood of Madras was infested by a gang of Thugs, and I succeeded in having a number of them caught and convicted. My native servant helped me in this, and partly for that reason I brought him to England with me, for a number of the gang were still at large, and a Thug, as you may know, will track a man the world over to be revenged.

"Years passed, and until to-night Amar Singh and I believed ourselves to be safe. Then came this mysterious visitor, whom I received. He proved to be one of the old band of Thugs, Ram Das by name, and his object was blackmail. He had been sent to England to find me, but he offered to keep my secret, and to reprt to his companions that he has failed, if I would pay him a large sum of money. I gave him twenty pounds in gold, promising to send him more, and when he had gone I bade Amar Singh follow him secretly and learn where he was stopping in the neighbourhood, that I might have him arrested in the morning.

"That is my explanation, Mr. Blake, and I trust that you will regard what I have told you as in confidence. The incident is closed for the present, since, after his murderous attempt on my servant, Ram Das will lose no time in escaping from England."

"It would be unwise to let him return to India," said Sexton Blake, who did not know how much of the story to believe. "I might be able to catch the fellow."

"No, I don't wish you to. I am anxious to avoid publicity."

"But the band will send others to murder you."

"I am not afraid," declared Lord Wargrave. "I shall cable the authorities at Madras, who will keep a lookout for Ram Das, and no doubt succeed in arresting him and his companions. Should I be threatened by any danger in the future, however, I will be glad to call in your assistance."

"And I shall be at your service."

"Meanwhile, Mr. Blake, you will respect my wishes?"

"In regard to Ran Das? I assure you that I have not the slightest idea of trying to bring him to justice. Good night, my lord!"

And with that Sexton Blake went off to bed, but not to sleep. For several hours he lay awake, pondering the strange events of the evening.

"Is it a very serious thing to compound a felony?" he asked.

"The law so regards it."

"Nevertheless, Mr. Blake, I want you to connive at one. It is often done, I believe, and in quarters not a thousand miles from Scotland Yard."

"What do you mean, my lord?"

"To come to the point, I have received a letter from the burglars, who appear to be aware how highly I value the stolen plate. They offer to restore it to me for a sum that is slightly in excess of its value as ordinary silver, and they declare that they will melt it down if I refuse."

"You think of accepting the offer?" asked the detective, who considered the statement to be quite plausible.

"I am most anxious to do so, naturally."

"You had better be guided by me, or you may lose both money and plate. Suppose you let me see the letter?"

"I am pledged not to show it to anyone," was the reply.

For an instant the eyes of the two men met, and Sexton Blake knew that Lord Wargrave was telling a deliberate lie --- knew that the whole story was a fabrication. Moreover, he knew in part the object of it.

"A clever scheme for getting rid of me," he thought. "Very well, my lord," he said, "you can manage this yourself. This is a case in which compounding a felony is at least excusable, and I sha'n't interfere. As there is nothing more for me to do here, I will go back to town at once."

"You have been put to considerable trouble," said Lord Wargrave, taking a cheque book from his desk, "not to mention loss of time, and I beg that you will ---"

"You owe me nothing," interrupted Sexton Blake.

"Surely you will let me pay you for your services?"

"No, my lord, I cannot accept a penny. I have been practically your guest for a day and a night. I have benefited by the change of air, and you have afforded me some pleasing excitement. That is compensation enough."

"As you will."

Lord Wargrave shrugged his shoulders, and put the cheque-book aside. Half an hour later he and the detective parted on the best of terms, and a small trap drove Sexton Blake from Wargrave Hall to the railway-station, where he caught a train before noon. Alone in a first-class compartment, he lit his pipe and sat with eyes half-closed, meditating on the strange events that had come to his knowledge.

"It is not all as clear as I could wish," he told himself. "There may be two intrigues going on. The tale about the Thug is possibly true in every respect -- I have known of such things -- and the letter that caused his lordship such annoyance refers to another unpleasant affair in India, concerning a child. But whether there are two blackmailers or only this one, it is certain that Lord Wargrave wanted to get me out of the way so that he might have a free hand; and he accomplished that at the sacrifice of his silver plate, which he will now never recover. No doubt he got a letter from the bogus Prince Nasrulla Khan by this morning's post -- a letter of defiance and threat -- and he means to purchase his safety by paying the whole sum that the scoundrel demands."

Thus the detective reasoned, mainly from idle curiosity; and on other points he worked out theories that equally satisfied him.

"After what happened last night," he thought, "the Hindoo won't trust himself at Wargrave Hall again, nor will he consent to a meeting anywhere in the vicinity. He has probably arranged in writing for an interview in town, among the crowds of London, and Lord Wargrave will ultimately meet him and pay over the money. On second thoughts, he may be hopeful of making the appointment at or near the Hall, and should the Hindoo consent to that -- which is more than doubtful -- he will be in no danger; for neither Lord Wargarve nor Amar Singh would dare to harm him, since they must know that I would be the first to suspect them of the crime. They meant to murder him last night, but they won't attempt that again.

"It is not an affair for me to meddle in. It is a case of blackmail, pure and simple, in which the victim intends to pay. I offered my assistance to Lord Wargrave, and he refused it. He is a rich man, and can afford to be bled, so I shall let him alone. On the other hand, however, it is just possible that there is something deeper than I imagine. Chester Carton, for instance, evidently knows something of Prince Nasrulla Khan's past. I shall look him up, and hear what he has to say about the matter. And it can do no harm to keep an eye on the Hindoo, if I can get on his track. I am pretty well convinced that he made his way back to town last night."

The train was gliding into Paddington Station, and Sexton Blake found himself looking forward with keen interest to pursuing his investigations, even while he felt they could lead to nothing more than he already knew.

He took a cab to Baker Street, ate his lunch, and started out in quest of the journalist, who had neither written to him nor left any message. But Chester Carton was not at rooms in Chancery Lane, and he could not be found in any of his usual haunts. The detective paid a second visit to Chancery Lane, drove west to the Anglo-Indian Club to make some inquiries about Lord Wargrave, and them went to Martinetti's restaurant in the Haymarket.

But Prince Nasrulla Khan was not dining there that night, which suggested that he has an appointment elsewhere, and, after waiting till past ten o'clock, Sexton Blake paid a third and fruitless visit to Chancery Lane. Then he drove home to Baker Street, and as he entered his sitting room Tinker appeared and handed him a telegram.

"It just came, sir," said the lad -- "not ten minutes ago."

Sexton Blake tore open the brown envelope, and an expression of puzzled bewilderment grew on his face as he read the following message, which had been sent from the night office at Hammersmith:

"I want your opinion in a mysterious affair. It is quite in your line. Come at once, if you can, to No. 483, Castletown Road, West Kensington. -- Dart."

The detective studied the signature with knitted brows.

"Dart? Dart?" he muttered. "Ah, I have it! My old friend Georges Dart, of course. How could I have forgotten him? But what could have brought him back to England?"

George Dart had served in India as a soldier in his early days, and after his discharge, while still a young man, he had joined the police force, and shown such a talent for detective work that he was speedily attached to Scotland Yard. Seven years ago he had gone out to India again, but this time to fill a post in the Secret Service, with headquarters at Madras. All this flashed upon the detective with the recognition of the name.

"Is it more than a coincidence?" he asked himself. "India has been buzzing in my brain all day, and now comes a message from Dart, whom I supposed to be thousands of miles away at Madras! What can he want with me?"

"Are you off again, sir?" inquired Tinker.

"Yes immediately! Run down and hail a cab, my boy, while I make a few quick changes. This may be a case for disguise."

Five minutes later -- it was now shortly past eleven o'clock -- Sexton Blake was driving rapidly through the gaslit streets of London, by the way of Park Lane, Knightsbridge, and Kensington High Street. The cab whipped through by a short cut to the North End Road, and turned off into the residential quarter of West Kensington --- a quarter that has seen better days -- where are imposing streets of brown stucco mansions, similar to those in Portland Place, though smaller in size.

No. 483, Castledown Road was such a house, with a wide portico and round columns supporting a heavy balcony. The nearest street-lamp was some distance off, and the detective could but vaguely see the faces of the little crowd who pressed about him curiously as he sprang to the pavement and mounted the steps. Here two constables were on guard, but at a word one of them opened the door.

"First floor back, sir," he said, touching his helmet.

All had been quiet and mysterious, and Sexton Blake felt a thrill of unwonted excitement as he mounted the staircase, at the top of which he was met by two men, one with black beard and eyeglasses, the other with a brick-dust complexion and a ragged, sandy moustache.

"My dear Blake," said the latter, in a subdued tone.

"My dear Dart! You look as young as ever!"

They clasped hands warmly, each scrutinising the other.

"This is Dr. Parry, whom I called in," said Inspector Dart.

"Glad to meet you," said Sexton Blake. "But may I ask what --"

"Come, I will show you," replied the inspector.

Sexton Blake pulled off his false moustache and slipped it into his pocket, as he followed his companions into an apartment that was bed-room and sitting-room combined. A triple gas-jet was burning, and the light shone on a man stretched full-length on a couch --- a dark- skinned man, with a black beard parted in the middle, whose eyes were closed, and whose limbs had a rigid appearance. For nearly a minute the detective gazed at the motionless figure, so absorbed that he did not hear voices in the hall or footsteps on the stairs.

"By heavens, it is Prince Nasrulla Khan!" he exclaimed.

"He called himself that," interposed the quiet voice of Chester Carton, as he entered the room and stood by the couch; "but his real name is Lalaje Ram!"

"You are quite right, sir, whoever you are," declared Inspector Dart. "The man you see before you is Lalaje Ram, the convict, and a pretty chase he has led me."

"I must apologise for intruding," said Chester Carton. "I am a journalist, and I am interested in this affair. I happened to know one of the constables at the door, and he allowed me to come in. Mt friend, Mr. Blake, will vouch for me. But is this man dead?" he added.

"He has been dead for more than an hour," replied Inspector Dart.

"Of heart disease," stated Dr. Parry.

"I take the liberty of doubting that," put in Sexton Blake.

"Ah, I thought you would!" said the inspector. "And yet there is no evidence to show that Dr. Parry is wrong."

"Not yet, perhaps," said Sexton Blake, in a peculiar tone, as he bent over the corpse. "What are the circumstances, Dart?"

"I will tell you all in a few words," replied Inspector Dart. "The dead man, Lalaje Ram, was at one time a havildar in the 2nd Indian Rifles, stationed at Dindigal, near Madras, and he also belonged to the infamous sect of Thugs. Thirteen years ago, in 1891, he was convicted of murder, and sentenced to imprisonment for life at the penal settlement on the Andaman Islands, in the Bay of Bengal. Six months ago he escaped, reached the mainland by hiding himself in a vessel that had brought supplies to the island, and the Indian Government instructed me to recapture him. I traced him across country to Madras and from there to Dindigal, where he made inquiries concerning a shikaree known as Jammu, who had disappeared shortly before Lalaje Ram's arrest --"

"Jammu?" interrupted Chester Carton, with an eager flush on his face. "Did you say Jammu?"

"Yes, that was the name," replied Inspector Dart. "At Dindigal I completely lost track of my man," he went on; "and not until weeks afterwards did it come to my knowledge that he had returned to Madras, and sailed from there in a vessel bound for England."

"You don't know where he spent those intervening weeks?" asked the journalist.

"I do not," declared Inspector Dart, who was surprised by the interruptions. "I haven't the slightest idea. As I was about to say, this new move on the part of Lalaje Ram puzzled the authorities, and instead of cabling to have the fugitive arrested --- they were curious to know why he had gone to England -- they ordered me to follow him. I took a faster steamer, and arrived in London a day or so earlier that the slow-sailing vessel. I spotted Lalaje Ram at the docks, and traced him to this house, where he took a room under the name of Prince Nasrulla Khan. That was five days ago. Yesterday I lost my man, but this afternoon I got on his track again, and this evening I shadowed him to a spot in Hyde Park near the Albert Memorial, where he waited for a couple of hours as if expecting someone."

"And nobody came?" put in Sexton Blake.

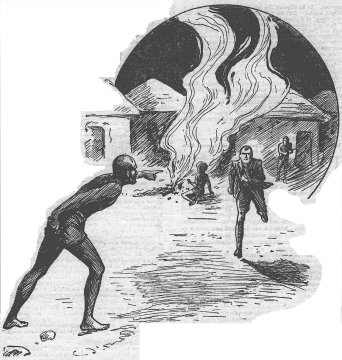

"Nobody came," replied Inspector Dart. "When the Hindoo finally left I followed him, but as I judged that he was going straight home I did not stick very close to him. In view of what happened afterwards, I regret that I kept so far behind. It may mean nothing, though I can hardly think so. But the facts are these, Blake. As I turned off the North End Road a man whizzed past me on a bicycle, and I got only a vague glimpse of him. I had then lost sight of my quarry. A minute later, as I turned into the Castletown Road, I heard the sound of a dull fall, and saw a dusky figure spring upon a bicycle. The man pedalled away as fast as he could go, down the street, and vanished in the darkness. I hurried forward to this house, which was twenty yards away, and on the upper step I found Lalaje Ram. He was lying partly against the door, and was already dead. It was from the front of the same house, or thereabouts, I may add, that the mysterious man jumped on his bicycle."

"It was a coincidence," suggested Dr. Parry.

"A very curious one, then," said Chester Carton.

"It was more than a coincidence," the inspector answered drily. "The cyclist had not been to any of the adjacent houses, for I took the trouble to inquire."

The doctor shrugged his shoulders. "Heart disease, Gentlemen," he said. "That is what killed the Hindoo."

"Look!" he exclaimed, in a tone of triumph.

"There is hardly anything to see," muttered Inspector Dart, as he bent over the arm. "What do you make of it?"

"It is a mere pin-prick," said Dr. Parry. "It amounts to nothing."

"On the contrary, it means everything!" declared Sexton Blake. "It means that this man was murdered by poison. I have been in India, and I know the signs. I amsatisfied, beyond a doubt, that the poison was derived from that most deadly and terrible of serpents known as the Echys Carinata. A single prick -- such as a puncture as you see -- would have been quite enough."

"You may be right, sir" said Dr. Parry. "I confess that I am not an expert in toxicology. I thought it curious that the body should have become so rigid so soon after --"

"He is right," broke in Inspector Dart. "I am sure of it. But what is your theory, Blake?"

"It is very simple," replied the detective. "This mysterious cyclist had an appointment in Hyde Park with Prince Nasrulla Khan -- or Lalaje Ram, I should say -- and he probably meant to murder him there. But he changed his mind --- I suggest that he saw you lurking about the vicinity -- and when the Hindoo left he followed him at a distance. He was, no doubt, provided with a short cane, which was fitted with a hollow needle that worked by a secret spring, and contained a few drops of the fatal venom. You can imagine the rest. As Lalaje Ram mounted the steps the cyclist darted at him, jabbed him in the arm, then sprang on his machine and fled. The prick of the needle would have produced instant paralysis of the throat and other muscles, as well as the heart, and the Hindoo must have died within a half dozen seconds."

"But what is the meaning of it all?" exclaimed Inspector Dart. "What brought Lalaje Ram to England? Why was he murdered in such a dastardly manner? This promises to be a most mysterious case."

"I think I can throw some light upon it." said the detective. "Lalaje Ram was killed by another Hindoo, and the assassin was urged to the deed by a third person. The two naturally believed that the cause of the man's death would not be discovered. I have a strong clue, which I obtained by accident. I have just returned from a big house in Berkshire, where I was summoned on professional business, and while there I happened to ---"

He was interrupted at that point by Chester Carton, who, with a sharp gesture, seized him by the arm and drew him aside.

"You have been to Wargrave Hall?" the journalist demanded, in an eager whisper.

"Yes, I have," Sexton Blake admitted.

"Then say no more! Drop the matter for the present! I want a quiet talk with you at the first opportunity."

"I am curious to hear the rest, Blake," interposed Inspector Dart. "This is my case, but I shall be glad of your assistance."

"I shall finish my story another time," replied the detective. "Where can I find you?"

"I am stopping at Scotland Yard."

"Very good!"

With that, Sexton Blake proceeded to thoroughly search the dead man, and then the room. On the body was a leather pouch containing English gold and a number of jewels, and under the bed he found a small box that contained some clothing purchased in London. That was all; there was nothing in the way of papers or writing.

"There is a matter I must speak of." Chester Carton said nervously, turning to the doctor and the inspector. "It is important that the true cause of the Hindoo's death should not be made known public, at least for a time. I want you to let the authorities believe that he died of heart disease. I hope that Mr. Blake will --"

"I am of the same opinion," interrupted the detective, who knew that the journalist must have a sound reason for the request. "I quite agree with my friend. So, for the present, gentlemen, let us hush this affair up."

"You think it best, Blake?" inquired the inspector, who was not a little mystified.

"I do. In the interests of justice."

"Yes; that the assassin may be thrown off his guard," said Chester Carton.

"That is understood between us, then," continued Sexton Blake. "I think I have finished here," he added. "You shall hear from me in the morning, Dart -- I promise you that. Good-night."

And he left the room in company with the journalist.

"Sit down!" urged the detective. "Have a drink and a cigar. They will help you to decide whether on not to take me into your confidence."

"No; I can't sit down," was the reply. "I am too nervous, too excited. As for my confidence, I have no intention of withholding that. You remember the episode at Martinelli's restaurant? Since then I have ben keeping an eye on Lalaje Ram, though I lost track of him yesterday. When I first saw him I suspected why he had come to England, and now, since I have learned what happened at Wargrave Hall, I know that I was not only right, but that there was much more in the Hindoo's visit than I dreamed of."

"You rouse my curiosity," said Sexton Blake.

"And I will satisfy it, for I want your help."

Chester Carton helped himself to a drink, lit a cigar, and sat down opposite to his companion. There was a reminiscent look in his eyes, which glowed with a strange, feverish light.

"I will begin with a little narrative that you have probably never heard of," he said. "At the time of which I am going to speak the late Lord Wargrave was a comparatively poor man. He had left Wargarve Hall to a rich American, and was living in chambers in London. He had been married twice, and had a son by each wife, both of whom were dead. The sons, who bore the family name of Haviland, were, of course, half-brothers, and had been in India for years. In the year 1891, which is the date of the story, Guy Haviland, the elder, was aged twenty-seven. He was a captain of the 2nd Native Rifles, stationed at Dindigal, in the province of Madras. Arthur Haviland, who was younger by three years, was private secretary to the Commissioner of Madras. I myself was living at Dindigal at the time, and Guy Haviland and I were bosom friends.

"To continue, my dear Blake, an insurrection broke out among the hill tribes up in the neighbourhood of Coorg, and Captain Haviland was sent against them with a small force. He left his wife and child behind him; and his body servant, I may add, was Lalaje Ram, who was a havildar in one of the companies of the regiment. One night the force encamped close to the stronghold of the enemy, and it was known that they meant to attack in the morning. They came at daybreak, and when the alarm was given Captain Haviland was lying in a stupor in his tent, utterly helpless. Deprived of their leader, the soldiers were beaten and compelled to retreat, and it was with great difficulty that they carried the young officer off with them. Captain Haviland was relieved of the command, and returned to Dindigal in disgrace, to learn that he was believed to have been intoxicated, returned to find that during his absence his wife had died of fever, and that his child, a little boy of three years old, had wandered into the jungle and fallen victim to a panther that was prowling about. Then came an order for the unhappy man to reprt himself for arrest, and this proved the last straw. A few hours later his clothes were found on the bank of a deep and sluggish river a mile away. He had committed suicide, and his body was never recovered, for the stream swarmed with crocodiles."

The journalist paused, and for a little time he was too deeply moved to speak. It was evident that he was still grieved for his friend, though many years had elapsed.

"I am deeply interested," said Sexton Blake. "From what you have already told me, and from what I learned at Wargrave Hall, I can see what is coming. His brother's death, of course, made the Honourable Arthur Haviland the heir to the title!"

"Certainly!"

"And to what else? To an empoverished estate?"

"No, far from it. A distant kinswoman, who had always been on bad terms with Lord Wargrave, had just died and left him property worth œ20,000 a year."

"Captain Haviland knew of this?"

"He did not," replied Chester Carton," for it was seldom that he heard from his father. But I am convinced that his half-brother, who was the favourite son, had been aware of the fact at some time. Do you see the drift? There was treachery and crime, so sure as there is a heaven above us. I never doubted my friend's innocence, nor, on the other hand, did I have any suspicions until a short time after his death, when I learned that Amar Singh, Arthur Haviland's servant, had been seen in Dindigal a day or two before the expedition started. He was devoted to his master, who had once saved him from a tiger. I put two and two together, and the truth flashed upon me. I firmly believe that Arthur Haviland sent Amar Singh to Dindigal, and that the latter bribed Lalaje Ram to drug Captain Haviland on the eve of the battle. Arthur Haviland, wanted the title and the estates. He hoped that his half- brother would perish in the fight, and later he would probably have disposed of the child who stood in his way had it not been carried off by a panther. You follow me?

"Go on," said Sexton Blake.

"I had no proofs," resumed the journalist, "so I could do nothing. Lalaje Ram, as you know, was a Thug, and not long after this affair he was arrested and taken to Madras. He was convicted on evidence raked up by Arthur Haviland -- who wanted to get rid of him -- and was sentenced to the Andaman Islands for life. Arthur Haviland resigned and went home, accompanied by Amar Singh, and for thirteen years -- his father died about the time of his return -- he has been the wealthy Lord Wargrave, enjoying life on the profits of a dastardly crime. I have been in England myself for ten years, longing to punish this guilty man, and now I see my way to do it. You remember what Inspector Dart told us to-night. Directly he spoke of Jammu --"

"Suppose you let me finish the story for you, "Interrupted Sexton Blake. "I think I can hardly go wrong. Lalaje Ram knew that he owed his conviction to Arthur Haviland, and knew the motive of it. He lived in the hope of escaping from the Andaman Islands, and at last he succeeded. He thirsted for vengeance, but he was influenced by a motive of a different kind ---namely, the suspicion that Captain Haviland's son was not dead. He made his way to Dindigal, and there learned that the child was indeed alive -- the child who is the real Lord Wargrave. He then came to England, went to Wargrave Hall, and offered to keep the secret in consideration of a large sum of money. Lord Wargrave and Amar Singh planned to kill him, and after the first attempt failed, not daring to pay a second visit to the Hall, Lalaje Ram appointed an interview in Hyde Park to-night. We know what happened. He waited in vain for Lord Wargrave, returned to West Kensington, and was followed and murdered by Amar Singh."

"You are right!" cried Chester Carton, rising excitedly to his feet. "There is not a shadow of doubt! What you learned at the Hall is the absolute proof of my suspicions! Had revenge brought Lalaje Ram to England he would have killed Lord Wargrave last night. But it was money he wanted. He chose blackmail instead of revenge. He knew that Captain Haviland's son was alive, knew where he could be found. And the clue is in my possession. There was never a certainty about the panther. The footprints of the beast were seen near the bungalow, that was all. Jammu, the shikaree, had a fondness for English children. He found the boy wandering in the jungle, yielded to the temptation to carry him off, and then suddenly vanished -- as I now remember -- from his little hut in the foothills. I have hardly thought of these things since, but the murder of Lalaje Ram has opened my eyes to the truth. The real Lord Wargrave is alive and with Jammu somewhere in that wild country!"

"I believe it, my dear fellow."

"Could you believe otherwise! Blake, you must go out to India! You must bring the heir back, restore him to his rights, and punish the false Lord Wargrave and Amar Singh! I employ you for this service! I will see it through at any cost!"

"I admire you, Carton. You are willing to spend all for the sake of a friend who has been dead for thirteen years!"

Chester Carton's face flushed. He turned his head for a moment, and rested his elbows on the mantel.

"You don't understand," he said. "Guy Haviland was more than my friend -- he was almost a brother. We were inseparable, and his terrible end spoilt my life. I want you to clear his name before the world. I want that guilty half-brother and his confederate brought to justice. And the boy -- the boy ---- "

He picked up his whisky-glass, and it fell to fragments to the floor, crushed by the pressure of his hand.

"Take another," said Sexton Blake, who was watching his friend narrowly. "By the way," he added, "I suppose you were doing journalistic work at Dindigal in 1891?"

"Yes," replied Chester Carton, as he poured out a drink. "Yes; I -- I was the correspondent of a Calcutta newspaper. I had to give up on account of the climate. I suffered from fever, and I never got rid of it. It is still in my bones, and it often sends me to bed for a day or two. That is why I dare not return to India; it would mean death! But I will provide the money, up to any amount. I could raise œ10,000, if necessary, within twenty-four hours."

Sexton Blake looked at the journalist in surprise.

"œ500 would be nearer the mark," he said. "But I am not thinking of the money. This will be no easy task. If the boy has been brought up by Jammu, the shikaree, he will be a young barbarian, I fear."

"Ah, that is the pity of it!"

"And it may be hard to trace him. It will be far more difficult -- nay, impossible -- to obtain evidence of guilt against Lord Wargrave and Amar Singh, since Lalaje Ram is dead."

"Yes, yes -- you are right. However, it will be punishment enough for Lord Wargrave to lose title and riches. Bring the boy back; that is all I ask. If Lalaje Ram was able to find him, why should you not do the same? Don't refuse, Blake! Promise me that you will go!"

"I will," replied Sexton Blake. "This is a case that strongly appeals to me -- it draws me like a magnet. Yes, I will go -- that is settled. But hadn't I better employ Inspector Dart to help me?"

"By all means! That is a good idea!" exclaimed Chester Carton. "The two of you can hardly fail to succeed."

"We will do our best, at all events," declared the detective. "But you are looking utterly fagged out, my dear Carton! Go home and sleep, and come back here to-morrow, when we will have a further talk over the matter."

"I will come in the afternoon; and, meanwhile, you can hunt up Inspector Dart and take him into your confidence. I hope the cause of Lalaje Ram's death can be kept a secret, for otherwise, should Lord Wargrave and Amar Singh have reason to fear that you suspect them of the crime, they might be a source of danger."

"That is true," assented Sexton Blake. "However, I don't think we need worry ourselves about it. Dart will know what to do. Good-night, my dear fellow!"

"Good-night!" said Chester Carton. "I am deeply grateful to you, Blake, and I have perfect confidence in your skill. Find Captain Haviland's son and it will be worth more to you than all the cases you have handled in the past."

At the end of the week Lalaje Ram was buried, after a coroner's jury had agreed that he had died a natural death, and, several days later, Sexton Blake and Inspector Dart sailed for India on a P. and O. liner. At Marseilles a wizened, grey-bearded old-Hindoo came aboard the vessel, but the detective and his companion did not observe the furtive scrutiny he gave them in passing, nor did they see him again during the voyage. Little did they imagine under what circumstances they were to meet him in the future.

"We shall not give up yet," vowed Inspector Dart.

"No; we are far from discouraged," declared Sexton Blake, "though I admit that the task has proved far more difficult than I expected it would. There are persons here -- or, at least, one person -- who can tell us what we want to know. It is certain that Lalaje Ram succeeded in getting the information, and I intend to do the same, no matter how long it may take."

There was a pause. It was an April night in India, more than seven weeks after the murder of the Hindoo in West Kensington, and the three men were sitting after dinner on the outskirts of Dindigal, which is a long distance from Madras, and far in the south of the vast province of that name. Mr. Lawrence was the assistant commissioner of the district, and Sexton Blake and the inspector had gladly accepted his offered hospitality while they engaged in the task that had brought them so many thousands of miles. So far, they had accomplished nothing, though they had been at Dindigal, working quietly and incessantly, for more than a fortnight. Natives in bazaars and suburbs, in neighbouring villages, had been questioned in vain. Many remembered Jammu and his mysterious disappearance, but not one would admit that he had seen Lalaje Ram on the occasion of his recent visit, or had given him any information. Yet somebody held the secret -- somebody who could not be bribed to open his lips.

"I recollect seeing you when you were here three or four months ago, Dart," said the commissioner. "I passed you in the street. You are sure of your facts, I suppose?"

"Quite sure," replied the inspector. "Half a dozen natives told me that they had seen Lalaje Ram, and that he had made inquiries of them concerning the old shikaree. I should have arrested the fellow at once, but I was keen on learning what he was up to, and that is how I lost him. He took alarm, and gave me the slip, and I heard nothing of his afterwards -- except that he had gone to the south . . . until it came to my knowledge weeks later that he had sailed from Madras to London."

"Well, there is still hope," said Mr. Lawrence. "The natives are a queer lot, and very reticent, though I see no reason for silence in this case. Perhaps the increased reward will induce the right man to come forward and speak."

Sexton Blake thoughtfully smoked his pipe for a moment, gazing into the tropical night, where the moon shone on field and jungle and distant hills.

"By the way, Mr. Lawrence," he said, "I think you told me that you were not living in Dindigal at the time of Captain Haviland's death?"

"No; I came here a year afterwards, while the sad affair was comparatively fresh."

"Captain Haviland had a very dear and intimate friend, a journalist by profession. His name was Carton -- Chester Carton. Did you ever hear of him, or meet him?"

"I never did," replied the commissioner. "The name is unfamiliar to me."

"That seems rather curious," said Sexton Blake. "I should have supposed that in so small a place --"

"What's that yonder?" interrupted Inspector Dart." Do you see it? I can't tell whether it is man or beast."

A vague, dusky object was moving slowly up the compound, following the edge of the path, and avoiding the moonlight by keeping in the shadow of the luxuriant plants and flowers. The shape soon resolved itself into a man. He crept warily nearer, occasionally turning his head to look back towards the gate.

"It is a native," muttered Mr. Lawrence. "But why does he behave so oddly?"

"He fears something," declared Sexton Blake. "This is the very man we want. You will see that I am right."

The mysterious person was now crouching at the foot of the verandah, between the steps and a clump of orange-bushes. He was an elderly Hindoo, scantily clad and without a turban.

"Who are you?" inquired the commissioner, "and what do you want?"

"My name is Govind, Lawrence sahib," was the reply. "I have come to speak with these sahibs, and to claim the reward of two hundred rupees. I can tell them what I told to Lalaje Ram."

"About the shikaree Jammu?" put in Sexton Blake. "Let us hear the story, and the money is yours."

"I am the sahib's servant," said the Hindoo, "and I will speak truthfully. Thirteen years ago, on the day that Jammu disappeared, I was cutting wood in the jungle, early in the morning, along the trail that goes south. At sunrise a cart passed by, drawn by a single bullock. The shikaree was walking alongside, and he did not see me, as I was hidden by the trees. From within the cart I heard the voices of two children, and I thought this was very strange, because I knew that Jammu had but one child of his own, a little boy called Vashti. But it was not my business, and I soon forgot the matter. Five years afterward, a fakir came through Dindigal -; he had once lived here -- and he told me that he had seen Jammu at the jungle village of Narpur, which is far to the south, and on the borders of the State of Kossa. More years passed, and a few months ago there came to my hut an old friend, Lalaje Ram, the havildar, who had escaped from the Andaman Islands. He questioned me about Jammu, and I told him what I have told you. Then he went away, after swearing that he would certainly kill me if I should ever reveal this information to anubody else. But I am very poor, and for a fortnight I have been tempted by the reward. Now I am here to claim it."

"You have done well," Inspector Dart told him. "But why did you crawl up the path like a skulking jackal?"

"Because I saw a man step into the bushes by the roadside as I approached, and I feared it might be Lalaje Ram. So I turned back, and went around by the fields, and when I came to the compound, I crept in on hands and knees that I might not be seen."

"You were mistaken," said Sexton Blake. "Lalaje Ram can do you no harm, for he is dead."

"Is this true, Lawrence sahib?" inquired the Hindoo.

"Yes; I can vouch for it," answered the commissioner. "Lalaje Ram is indeed dead."

Govind doubted no longer. He trembled with happiness as the two hundred rupees were given to him in a bag, and then, with profuse expressions of gratitude, he went off, striding boldly down the path and into the road.

"Gentlemen, I congratulate you," said Mr. Lawrence. "You have obtained the information that you wanted, and it can be relied upon."

"I am satisfied of that," assented Sexton Blake. "We are near the end of our quest, for one of the children in the cart was certainly Captain Haviland's son -- the real Lord Wargrave. As to whether the boy is alive or not, that is a far different matter. But we will hope for the best. How far is this village of Narpur, Mr. Lawrence?"

"Nearly a hundred miles, straight to the south, and by a rough and lonely jungle trail, which is seldom used. However, there are one or two dak-bungalows on the way. The village is just outside the territory of the Nawab Pershad Jung, who rules over the little native state of Kossa. He is a poor sort of a ruler, though. His revenues are small, and he squanders every rupee in riotous living."

"Well, a hundred miles is not much of a journey," said Inspector Dart. "But what about that man in the bushes?" he inquired uneasily.

"I don't believe he existed," replied the commissioner. "The Hindoo was thinking with terror of Lalaje Ram at the time, and his imagination deceived him."

"I agree with you," said Sexton Blake, as he rose and knocked the ashes from his pipe. "We had better go to bed," he added, "for I want to start for Narpur as early as possible to-morrow morning, and there are arrangements to be made first."

"I don't like this," said the inspector. "It will soon be too dark to see a yard in front of us. I once camped out with a surveyor, up in Bengal, and during the night the poor fellow was carried off by a tiger from my very side. I wonder if our guide knows what he is doing?"

"He seems positive about it," Sexton Blake answered. "Have we far to go yet, Shahvani?"

"Not far, sahib," was the reply. "We shall soon be there."

The guide had said the same thing more than once during the last half-hour, but this time he proved to be right. A few minutes later, to their relief, the travellers came to a little building of bamboo, with a thatched roof, that stood by the side of the trail. It was a dak-bungalow, a shelter-house such as the Indian Government thoughtfully provide in lonely parts of the country, and at one end of it was a sort of a shed for horses.

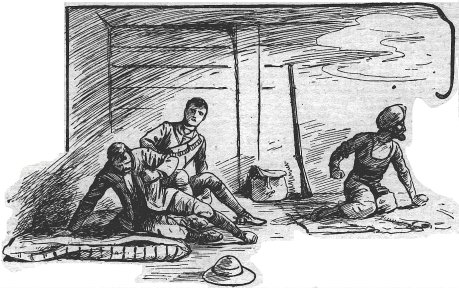

The ponies were put up for the night and fed, and then, twilight having already fallen, the three men entered the bungalow. It was so little used that no caretaker was employed, as is often the case; but when a clay lamp had been found and lighted -- it was half-full of oil -- the place was seen to be quite dry and in fairly good preservation. There was a small table, a mat on the floor, and in one corner a large mattress stuffed with dried grass.

"This is snug enough," declared Sexton Blake. "We must see that there are no venomous snakes about, though."

None having been found, the door was closed, and supper was prepared and eaten. Then Shahvani curled himself up on the mat and fell asleep, while the Englishmen, who were not drowsy, settled themselves on the mattress, with their backs to the wall, and lit their pipes. They had left the lamp burning, and their rifles lay within reach. On the opposite side of the room, and near to the farther end, was a narrow window with a blind of rice matting. The cries of wild animals could be heard far off, but none appeared to be anywhere near the bungalow.

"This is one of the strangest cases I have ever undertaken," said Sexton Blake. "Yesterday it promised to drag out interminably, but now I think the end is in sight. That Lalaje Ram went to Narpur, and found the boy there, can hardly be doubted. A long interval elapsed before he sailed to England, but we must remember that he had to go hundreds of miles to Madras, and probably on foot."

"If the boy has been with Jammu all these years," replied Inspector Dart, "he will be little better than a native. And to think of his being Lord Wargrave!"

"He will have to be educated," said the detective, "and as he is only sixteen, he will be quick to learn. There is one thing that puzzles me," he added. "I mean the letter that Lord Wargrave received from India. If it only arrived that night, four or five days after Lalaje Ram reached England----"

He was interrupted by the sharp report of a firearm, and with that, uttering a gasping cry and clapping his hand to his breast, Inspector Dart toppled over on his side. Up jumped Shahvani with a yell of terror, and for an instant Sexton Blake saw the gleam of a weapon and a swarthy face at the window. Then the Hindoo knocked over the table and extinguished the lamp, and to that fortunate circumstance the detective undoubtedly owed his life; for, as the room was plunged in darkness, he heard the hum of a bullet by his ear. Another shot barely missed him as he sprang to his feet, and, drawing a revolver from his belt, he emptied three chambers in the direction of the window. Silence followed, save for the wailing of the frightened native.

There was no reply. Sexton Blake groped for his rifle and found it. He crept to the door, threw it open and ran fearlessly around to the rear of the bungalow. The moon was shining, and there was nobody there; but he could hear crashing footsteps tearing through the jungle, telling him that the assassin was in headlong flight. He listened for a moment, and then, hurrying back, he struck a match and relit the lamp, which had not been damaged.

He was relieved by what he saw. The Hindoo -- he was a brave enough fellow -- had recovered from the fright caused by the sudden awakening, and was holding a flask of water to the lips of Inspector Dart, who was sitting upright on the mattress. He took a long pull, and then rose unsteadily to his feet, breathing heavily in short, quick gasps.

"Where are you hit?" exclaimed Sexton Blake.

"I don't believe I'm hit at all!" declared the inspector, as he opened his coat, "though I feel as if my chest was caved in. Ah, look at this!"

And he produced from an inner pocket a square tobacco-box of thick metal. The bullet had torn through the lid of it, glanced off the bottom, and ripped its way out at one end.

"By Jove, that saved your life!" said Sexton Blake.

"It certainly did, old man. I had a narrow escape. The shock bowled me over, and I was stunned for a few seconds. I'm none the worse, however, except for a soreness about the rubs. But who the deuce could have tried to murder me?"

"I had only a glimpse of the man -- a glimpse of a brown face and a pair of wicked eyes. When I rushed out he made off like a deer."

"He was a dacoit, or a Thug," suggested Shahvani. "Evil budmashes sometimes prowl in the jungle to kill and rob sahib travellers."

Sexton Blake shrugged his shoulders.

"The fellow may come back," he replied, "and if so we must be ready for him. Shahvani, you take the first watch here by the window. Call us at once if you hear any suspicious noise outside, and in any event waken one of us in a couple of hours."

That the Hindoo was right, and that travellers in these desolate parts were subject to peril, seemed likely from the means of security that had been provided. The ponies had been locked in the shed from the first, and now the door of the bungalow was fastened with two stout bars. The lamp having been extinguished, the detective and his friend moved the mattress to the opposite corner of the room and stretched themselves upon it, while Shahvani squatted on the floor close beneath the window, through which streamed a pale ray of moonlight.

"Do you hear that?" said Inspector Dart, as the roar of a tiger echoed across the solitude of the forest. "Our murderous visitor will probably make a meal for Mr. Stripes."

"I hope he will. I should like to feel that we were rid of him. The scoundrel meant to kill us both, Dart, and he very nearly succeeded. The tobacco-box saved you from the first shot, and the second shot would have certainly struck me if Shahvani hadn't knocked the lamp over. It was a bold piece of work."

"Too bold," replied the inspector. "I don't quite understand it. I've had some experience with dacoits and Thugs, and prowling rogues of all sorts, but I've never known any of them to show such daring. They usually attack in the dark, and use a dagger or a sword."

"I agree with you," said Sexton Blake. "Of course, the fellow may have been an ordinary jungle rogue, but I strongly doubt it. In fact, I have an ugly suspicion in my head, and can't get it out."

"What is it?"

"That our late visitor was none other than Amar Singh."

"Amar Singh?" gasped the inspector. "Lord Wargrave's servant? He is thousands of miles away! It is impossible that he could be here."

"Not at all, my dear fellow. Lord Wargrave would naturally have been alarmed after my visit to the Hall. He might have learned that you and I were going to India, and suspected for what purpose. Suppose that Amar Singh was sent after us, that he travelled overland to Marseilles and joined our boat there, that he shadowed us to Dindigal, and that he followed us on horsebakc to-day at a safe distance? You remember the old Hindoo at Marseilles?"

"Distinctly. Yes, he may have been Amar Singh. But if so, he was wonderfully disguised."

"And the man whom Govind saw in the bushes last night."

"Amar Singh again! He must have been watching the commissioner's bungalow on the chance of learning if we had discovered anything. You have proved your case, Blake."

"No, I am not sure of all this!" replied Sexton Blake. "I am only theorising, and I may be wrong. But the circumstances look suspicious, to say the least, and hereafter we must be constantly on our guard. If Amar Singh is tracking us he will be a terribly dangerous foe, for he will do his best to kill us."

"He will hardly come back to-night," said the inspector.

"No, not after his failure. He will wait for another opportunity."

The subject was discussed until the two men fell asleep, and they knew nothing more until they woke in the early dawn, to find Shahvani slumbering soundly on his mat by the window, which carelessness gained him a severe scolding. The ponies were safe, and, after a hurried breakfast, the three mounted and set forth.

That night they reached another dak-bungalow, where they kept watch by turns until morning. Then they resumed their journey through the dense jungle, and when they came in sight of Narpur towards evening of the same day, they regarded their adventure of the first night with less apprehension.

"I begin to think you were wrong, Blake," said inspector Dart.

"It looks rather like it," replied the detective. "However, we'll not relax our vigilance."

Here dwelt a small community of perhaps a hundred souls, far from any habitation, and in the heart of a dense jungle that stretched for many miles in every direction. An ancient wall enclosed the village as a protection from wild beasts and dacoits, and in this was set a massive wooden gate.

Sexton Blake rapped upon it with the butt of a pistol, and it was opened by a native who, after some questions, reluctantly permitted the party to enter. Passing through, they beheld a narrow street that led to another gate. On both sides were rows of huts, and in the middle was the usual water-tank, covered with lotus blossoms.

As the travellers dismounted, men, women and children gathered about them, and presently appeared the zemindar or head man --- an elderly, dignified Hindoo, in a calico turban and a white robe,

"I am Gamesh," he said, "and these are my people. If you mean us no harm you are welcome."

"The sahibs are friendly," the guide told him. "They would speak with you on a certain matter."

No more was said for the present. Shahvani led the ponies away, and a few moments later, as the sun was sinking behind the jungle, Sexton Blake and Inspector Dart sat outside the zemindar's little house under a canopy of leaves. The host handed around a tray of betel-nuts, which were refused with thanks. He took one himself, and his lips were soon stained with the pink juice.

"We have come a long distance," began the detective, "and hope that you may be of service to us. We seek a shikaree named Jammu, and we were told that we should find him at Narpur. Is this true?"

"It is true no longer, sahib," was the disappointing reply that Gamesh gave. "Well do I know Jammu, the shikaree, though he was not one of us. Thirteen years ago he came here, but he would not dwell within the village. He built himself a little hut in the jungle, and there he lived with his two sons, now in the State of Kossa, from what I have heard."

"And the two children were alive?" inquired Inspector Dart. "He took them with him when he left here?"

"He took the boy Bala," replied the zemindar, "but I am not sure about the other son. Vashti had already fled from his father's care, and yet he was but ten years old. Is it possible, sahibs, that you have not heard of Vashti, the panther boy?"

"No," said Sexton Blake. "What of him?"

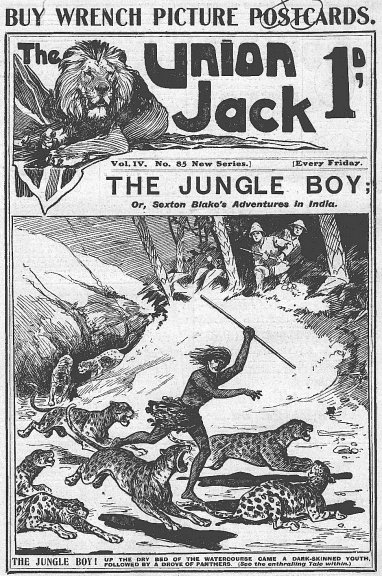

"It is a strange story," was the answer. "From an early age the young Vashti showed no fear of wild animals. Indeed, he had a wonderful power over them, and they seemed to be attracted by him in the same way. Once he boldly stroked a tiger that came close to our walls, and another time he was seen fondling a great leopard. For days he would disappear, returning frequently to his father's hut; and it is possible that he went with Jammu to the south. Of that I am uncertain, but this much I know. Time and again, during the last six years, men from my village who have gone towards Kossa, have seen Vashti tearing like the wind through the jungle accompanied by a pack of a dozen fierce panthers. For that reason he is called the panther boy, and he is shunned and dreaded by all. What I have told you is the truth, sahibs."

The detective and his friend glanced at each other incredulously. To accept this amazing tale was to great a strain for their imagination, though they could well believe that the boy had wandered into the jungle and been lost. But which of the two was it?

"Did these sons of the shikaree look alike?" inquired Sexton Blake.

Gamesh shook his head.

"They were very unlike," he replied, "and some have said that they could not have been brothers. They were the same in age and height, but while Vashti was the image of his father, the young Bala was not so dark of skin, and had blue eyes."

"That settles it," murmured Inspector Dart.

"You think that the boy Bala is now with his father?" asked Sexton Blake, whose anxiety had been relieved.

"How should I know that?" replied the zemindar. "The boy went away from here with his father six years ago. Of Bala I am ignorant, but I have been told that Jammu took service as a shikaree with the Nawab of Kossa, and that he dwells in the jungle near to the palace, and to the village of Talnagore."

"And how far must we go to reach there?" asked the inspector.

"The distance is about thirty miles," said Gamesh, "buy you may be turned back from the frontier if you meet any of his Highness's soldiers, who are always on the watch. The Nawab Pershad Jung dislikes strangers, and he will not allow them to shoot in his territory, even if they ask for a permit."

"That won't keep us away!" vowed Sexton Blake.

"It is none of my concern," said Gamesh. "The sahibs are their own masters. There was another man -- a Hindoo -- who asked these same questions of me some time ago. He also went down into Kossa, and he has not returned."

"Well, we'll take the risk," said the detective, with a glance at the inspector. "We shall start for Talganore at day-break," he added, "and we will be grateful if you can offer us shelter for the night."

"You are welcome to that, sahibs," replied the zemindar. "You shall have food and a bed."

Darkness had now fallen, and presently a tempting repast was served to the two Englishmen, including delicious fruits and curried rice. When they had finished the meal -- Gamesh's caste forbade him to share it with them -- they were escorted to a small hut near the south gate. Here their saddle-bags had already been brought, and on the floor were beds of dried grass. They sat down in the doorway and lit their pipes, enjoying the cool air of the evening.

"I rather counted on finding our young lord here," said Inspector Dart.

"No more than I did," replied Sexton Blake. "However, we have nothing to complain of. We are on the right track, and we have only thirty more miles to go. By this time to-morrow our search ought to be ended. The boy, Bala, is certainly Captain Haviland's son, and I trust we shall find him with the old shikaree at Talnagore. A few rupees, and a promise of immunity, will no doubt induce Jammu to make a full confession. As for the Nawab Pershad Jung, I don't think he will interfere with us."

"He wouldn't dare to," said Dart. "I suppose he is held in check by a British resident."

"I fancy not. Kossa is too insignificant a State for a resident, though there is probably a political agent attached to the Court,"

"We'll have to hunt him up, then, so that our business may be done ship-shape and legally. By the by, what of the pretty yarn the zemindar told us about Vashti, the panther boy? There isn't a world of truth in it, of course."

"It is hard to credit, I admit," replied Sexton Blake; "but strange things happen in India, and our friend Gamesh seemed to be very much in earnest."

"When I see this panther boy with my own eyes," said Dart, "then I'll believe the tale."

An hour passed, and from the surrounding jungle came cries of prowling wild beasts. Within the village all was peace and quiet. One by one the little clay lamps were snuffed out, and finally the zemindar's house was darkened. Near the water-tank a native was huddled by a fire of blazing wood, which was doubtlessly intended to frighten off any hungry tiger or leopard that might otherwise leap the walls.

"We had better follow the general example, and turn in," suggested Sexton Blake. "These are snugger quarters than a dak-bungalow."

"And safer," said Dart, rising with a yawn. "No prowling dacoit will bother us here."

They emptied their pipes, entered the hut, and were soon sleeping side by side on the beds of sweet-scented grass.

The tropical night crept on. The fire by the tank burnt low, and the sentry --- his head sunk on his shoulders --- was slumbering at his post.

It was between two and three in the morning when Sexton Blake suddenly woke as if something had startled him. He heard a faint rustling noise, which put his senses on the alert, and the next instant, before he could realise that danger was near, he saw a dim form bending over him, and caught the dull gleam of steel.

As he threw himself to one side, there was the sound of a blow striking the bed on the spot where he had been lying. He sprang up, reached for the startled intruder, and, by good luck, seized a wrist that was descending with murderous intent, giving it such a jerk that a weapon flew against the wall.

"Dart! Dart!" he cried.