unknown and nameless horror, to be unable to

defend himself ... it was these things that almost unstrung him; to be

able to use his fists, to put up some sort of defense, to inflict punishment

upon his adversary . . . then he could face death with a smile. It was

not death that he feared now ... it was the horror of the unknown that

is part of the fiber of every son of woman.

Closer and closer came the shapeless mass. Bradley lay

motionless and listened. What was that he heard! Breathing? He could not

be mistaken . . . and then from out of the bundle of rags issued a hollow

groan. Bradley felt the hair rise upon his head. He struggled with the

slowly parting strands that held him.

The thing beside him rose up higher than before and the

Englishman could have sworn that he saw a single eye peering at him from

among the tumbled cloth. For a moment the bundle remained motionless .

. . only the sound of breathing issued from it, then there broke from it

a maniacal laugh.

Cold sweat stood upon Bradley's brow as he tugged for

liberation. He saw the rags rise higher and higher above him until at last

they tumbled upon the floor from the body of a naked man ... a thin, a

bony, a hideous caricature of man, that mouthed and mummed and, wabbling

upon its weak and shaking legs, crumpled to the floor again, still laughing

. . . laughing horribly.

It crawled toward Bradley. "Food! Food!" it screamed.

"There is a wav out! There is a wav out!"

Dragging itself to his side the creature slumped upon

the Englishman's breast. "Food!" it shrilled as with bony fingers and its

teeth, it sought the man's bare throat.

"Food! There is a way out!" Bradley felt teeth upon his

jugular.

He turned and twisted, shaking himself free for an instant;

but once more with hideous persistence the thing fastened itself upon him.

The weak jaws were unable to send the dull teeth through the victim's flesh;

but Bradley felt it

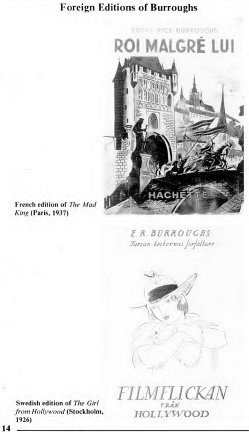

Foreign Editions of Burroughs

|

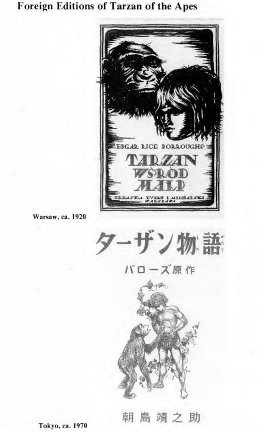

Foreign Editions of Tarzan of the Apes

|

gnawing, gnawing, gnawing, like a monstrous rat,

seeking his life's blood.

The skinny arms now embraced his neck, holding the teeth

to his throat against all his efforts to dislodge the thing. Weak as it

was it had strength for this in its mad efforts to eat. Mumbling as it

worked, it repeated again and again. "Food! Food! There is a way out!"

until Bradley thought those two expressions alone would drive him mad.

1

The above excerpt from "Out of Time's Abyss" (part

III of the trilogy) shows Burroughs in typical stride.

His personal identification with the fictional character

of Bradley is unmistakable. In such moments his prose style is gripping,

the words interacting in a harmonious pull towards the climax of the scene

(which ends, needless to say, in an honorable solution for both participants).

If one were to rewrite this scene, it would be difficult

to select another combination of words and sentences more effective than

those chosen by Burroughs himself. Even the variant spelling of "wabbling"

for wobbling seems somehow appropriate. His expression was spontaneous

and he rarely rewrote his stories, preferring to leave them as they first

tumbled from his imagination, checking only for spelling, punctuation,

and occasional non-sequiturs in his plots.

In later years he used a dictaphone to ensure their virginal

authenticity.

The stuff of which he builds his heroes is underscored

time and time again with subliminal appeal. Through every encounter with

savage men and beasts, the reader is constantly assured of the hero's superior

attitude toward danger and death. A familiar example from Tarzan at the

Earth's Core runs as follows:

From childhood he had walked hand in hand with

the Grim Reaper and he had looked upon death in so many forms that it held

no terror for him. He knew that it was the final experience of all created

things, that it must as inevitably come to him as to others and while he

loved life and did not wish to

1Copyright 1918 Story Press

Corporation.

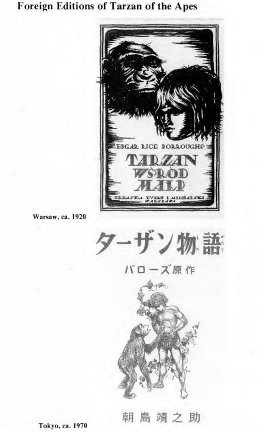

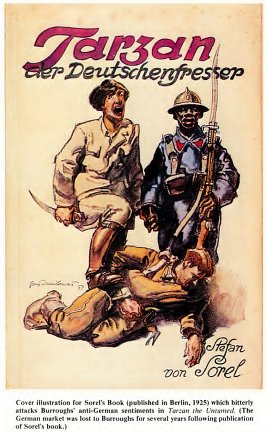

Cover illustration for Sorel's Book (published in Berlin, 1925)

which bitterly

attacks Burroughs' anti-German sentiments in Tarzan the Untamed.

(The German market was lost to Burroughs for several years following

publication of Sorel's book.)

die. its mere approach induced within him no

futile hysteria. 2

Most of us recognize in this passage an obvious parallel

in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar:

Cowards die many times before their deaths;

The valiant never taste of death but once.

Of all the wonders that I yet have heard.

It seems to me most strange that men should fear;

Seeing that death, a necessary end.

Will come when it will come.

Whether Burroughs read Shakespeare or drank from the same

fountain is not important. The message cannot be too often drummed into

responsive ears.

Throughout the generations of Burroughs readers, many

have scanned the author's mentality for some hint of a religious conviction

coinciding with their own. They are invariably brought back to a nondenominational

premise with which time has found no fault. A typical sounding of this

theme runs as follows:

Tarzan of the Apes was not a church man; yet

like the majoritv of those who have always lived close to nature he was,

in a sense, intensely religious.

His intimate knowledge of the stupendous forces of nature,

of her wonders and miracles, had impressed him with the fact that their

ultimate origin lay far beyond the conception of the finite mind of man.

and thus incalculably remote from the farthest bounds of science.

When he thought of God he liked to think of Him privately,

as a personal God. And when he realized that he knew nothing of such matters,

he liked to believe that after death he would live again. (Tarzan

at the Earth's Core)

Burroughs frequently ruminates on the future of man ("those

two footed harbingers of strife") in a cynical vein, indulging his pet

peeves to the fullest:

2. Copyright 1929. 1930 Edgar

Rice Burroughs. Inc.

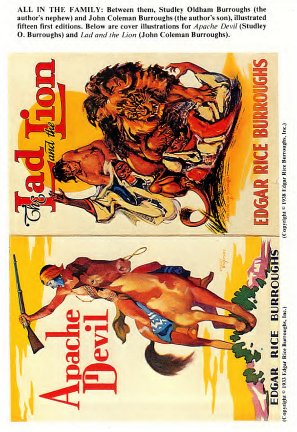

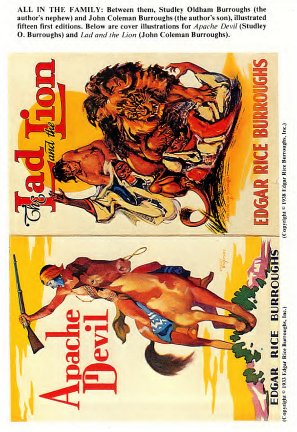

ALL IN THE FAMILY: Between them, Studley Oldham Burroughs (the author's

nephew)

and John Coleman Burroughs (the author's son), illustrated fifteen

first editions.

Featured here are cover illustrations for Apache Devil (Studley

O. Burroughs)

and Lad and the Lion (John Coleman Burroughs).

Perhaps, thought Gridley, in nature's laboratory

each type that had at some era dominated all others represented an experiment

in the eternal search for perfection. The invertebrate had given way to

fishes, the fishes to reptiles, the reptiles to the birds and mammals,

and these, in turn, had been forced to bow to the greater intelligence

of man.

What would be next? Gridley was sure that there would

be something after man, who is unquestionably the Creator's greatest blunder,

combining as he does all the vices of preceding types from invertebrates

to mammals, while possessing few of their virtues.

Yet Burroughs was comfortable with human nature, understanding

it like an indulgent parent, and usually couching his observations in wry

humor. When his twentieth-century hero meets a Stone Age girl who is attracted

to him, her first desire is to teach him her language. Thus Burroughs muses:

What will not one do to have one's curiosity

satisfied, especially if one happens to be a young and beautiful girl and

the object of one's curiosity an exceptionally handsome young man? Skirts

may change, but human nature never.

Humor in facing a potentially tragic situation is a Burroughs

trademark. A random sampling of this appealing technique occurs in the

capture of Tarzan and his friends by a tribe of Stone Age savages at the

Earth's core who tie them up and then retire to decide their fate:

They knew that outside upon the ledge the warriors

were sitting in a great circle and that there would be much talking and

boasting and argument before any decision was reached, most of it unnecessary,

for that has been the way with men who make laws from time immemorial —

a great advantage, however, lying with our modern lawmakers in that they

know more words than the first ape-men.

Burroughs had definite ideas on many subjects, one of them

being modern art. With cynical humor he causes Carson of Venus

to comment on the crazy-quilt palace of the Myposans as follows:

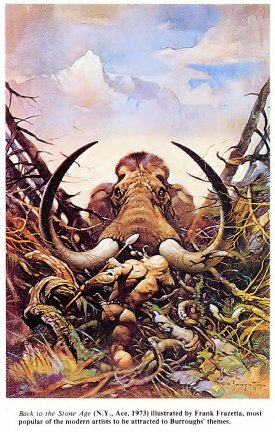

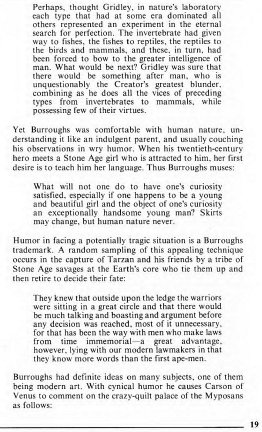

Back to the Stone Age (N.Y., Ace, 1973) illustrated by Frank

Frazetta,

most popular of the modern artists to be attracted to Burroughs'

themes.

.

. . it might have been designed by a drunken surrealist afflicted with

a hebephrenic type of dementia praecox; which, of course, is not normal,

because surrealists are not always drunk. I sometimes think that man's

inability to reproduce the beauties of nature has led to the abominable

atrocities called Modern Art. 3

.

. . it might have been designed by a drunken surrealist afflicted with

a hebephrenic type of dementia praecox; which, of course, is not normal,

because surrealists are not always drunk. I sometimes think that man's

inability to reproduce the beauties of nature has led to the abominable

atrocities called Modern Art. 3

Occasionally the public is amazed by the sudden appearance

of a new talent in the form of an individual of little or no previous training,

yet whose command of his art suggests a lifetime of preparation.

The Metropolitan Opera Company makes such a claim for

its former baritone Leonard Warren. Burroughs fits this description ideally.

With a sort of prescience he instituted his famous "cliff-hanger" technique

in the first Tarzan novel, leaving the way open for his special talents

to devise endless sequels.

Perhaps the finest example of the Burroughs cliff-hanger

occurs at the end of Tarzan of the Apes. The hero has just

received verification of his noble birth in a telegram, but conceals the

information, believing that the woman he loves will find greater happiness

with Cecil Clayton (his civilized cousin who has inherited Tarzan's title

and estates as next-of-kin). As Clayton shakes the hand of the mysterious

stranger, he asks:

"If it's any of my business, how the devil did

you get into that bally jungle?"

"I was born there," said Tarzan quietly. "My mother was

an Ape, and of course she couldn't tell me much about it. I never knew

who my father was."

Immediately beneath, in large letters, is written: "THE END."

Beneath this, in a publisher's footnote, we read:

The further adventures of Tarzan, and what became

of his noble act of self-renunciation, will be told in the next book of

Tarzan. 4

And sure enough . . .

3. Copyright 1938 Frank A.

Munsey & Co

4. Copyright 1914 A. C. McClurg and Co.

Obituaries

and Rebirths

Obituaries

and Rebirths

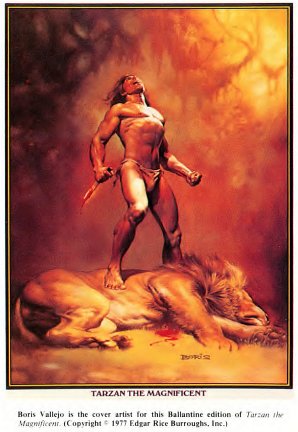

There has always been a prevailing westerly wind in the

publishing business which whispers to us that the works of all popular

writers are ephemeral and hardly worth saving. When posterity alters this

concept by producing exceptions the bookdealers have a field day! The highest

recorded price ever paid for a first hardcopy edition of Tarzan of

the Apes was $3,600 in 1979. (Dickens, Milton, even Shakespeare

rarities may still be got for less.) What does this mean? To whom is Burroughs

worth this kind of money?

The answer lies in the repeated assertions of literary

historians that Burroughs has earned the title of "Father of American Science-Fiction.

" His Chicago upbringing and hard won success story are typically American,

even though his writings deal largely in extra-terrestrial fantasies which

are the province of all writers of any nationality.

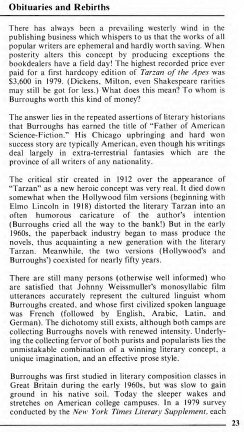

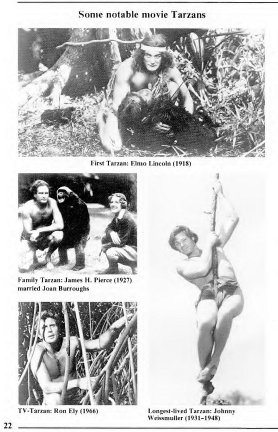

The critical stir created in 1912 over the appearance

of Tarzan" as a new heroic concept was very real. It died down somewhat

when the Hollywood film versions (beginning with Elmo Lincoln in 1918)

distorted the literary Tarzan into an often humorous caricature of the

author's intention (Burroughs cried all the way to the bank!)

But in the early 1960s, the paperback industry began to

mass produce the novels, thus acquainting a new generation with the literary

Tarzan. Meanwhile, the two versions (Hollywood's and Burroughs') coexisted

for nearly fifty years.

There are still many persons (otherwise well informed)

who are satisfied that Johnny Weissmuller's monosyllabic film utterances

accurately represent the cultured linguist whom Burroughs created, and

whose first civilized spoken language was French (followed by English,

Arabic, Latin, and German).

The dichotomy still exists, although both camps are collecting

Burroughs novels with renewed intensity. Underlying the collecting fervor

of both purists and popularists lies the unmistakable combination of a

winning literary concept, a unique imagination, and an effective prose

style.

Burroughs was first studied in literary composition classes

in Great Britain during the earlv 1960s, but was slow to gain ground in

his native soil. Today the sleeper wakes and stretches on American college

campuses. In a 1979 survey conducted by the New York Times Literary Supplement,

each

23

Some Notable Movie Tarzans

First Tarzan: Elmo Lincoln (1918)

Family Team: James H. Pierce (1927) married Joan Burroughs

Longest-lived Tarzan: Johnny Weissmuller (1932-1948)

TV Tarzan: Ron Ely (1966)

|

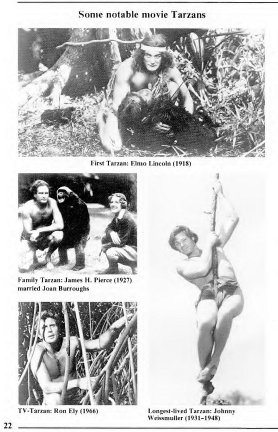

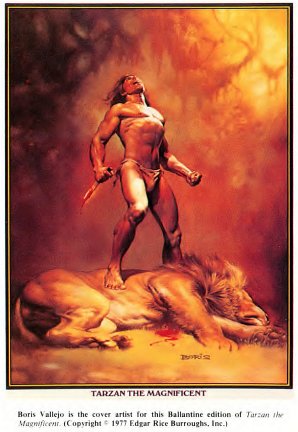

TARZAN THE MAGNIFICENT

Boris Vallejo is the cover artist for this

Ballantine edition of

Tarzan the Magnificent.

(Copyright © 1977 Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

|

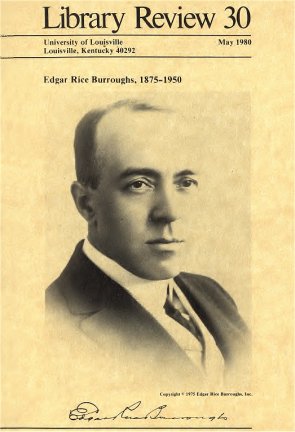

member

of a panel of literary critics was asked to name his personal candidate

for the most neglected American writer of the twentieth century. Burroughs

was on the list.

member

of a panel of literary critics was asked to name his personal candidate

for the most neglected American writer of the twentieth century. Burroughs

was on the list.

Regardless of how the tide may turn in years to come,

the University of Louisville Library will remain a unique repository for

a unique writer . . . the incomparable king of dreams, Edgar Rice Burroughs.

GTM

Humor Footnote:

In a radio interview on September 3, 1940, Burroughs

was asked the favorite reporter's question: "How did you conceive of Tarzan

as an English Lord reared by apes?"

Burroughs replied characteristically: ". . . The more

I thought about it, the more convinced I became that the resultant adult

would be a most disagreeable person to have about the house. He would probably

have B.O., Pink Toothbrush, Halitosis, and Athlete's Foot, plus a most

abominable disposition.

So I decided NOT to be honest, but to draw a character

people could admire.

Burroughs

had a musical flair for creating fictitious names, and any stylistic account

(no matter how brief) would be abortive were it not to include examples.

He often bracketed a phonetic spelling of names to give his readers a clear

idea of their pronunciation.

Burroughs

had a musical flair for creating fictitious names, and any stylistic account

(no matter how brief) would be abortive were it not to include examples.

He often bracketed a phonetic spelling of names to give his readers a clear

idea of their pronunciation.

.

. . it might have been designed by a drunken surrealist afflicted with

a hebephrenic type of dementia praecox; which, of course, is not normal,

because surrealists are not always drunk. I sometimes think that man's

inability to reproduce the beauties of nature has led to the abominable

atrocities called Modern Art. 3

.

. . it might have been designed by a drunken surrealist afflicted with

a hebephrenic type of dementia praecox; which, of course, is not normal,

because surrealists are not always drunk. I sometimes think that man's

inability to reproduce the beauties of nature has led to the abominable

atrocities called Modern Art. 3

Obituaries

and Rebirths

Obituaries

and Rebirths

member

of a panel of literary critics was asked to name his personal candidate

for the most neglected American writer of the twentieth century. Burroughs

was on the list.

member

of a panel of literary critics was asked to name his personal candidate

for the most neglected American writer of the twentieth century. Burroughs

was on the list.