Editor's Preface

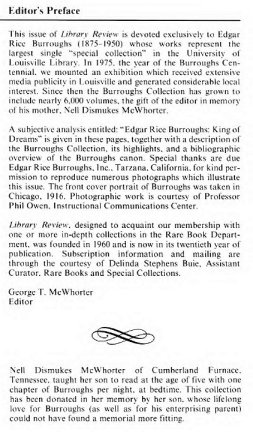

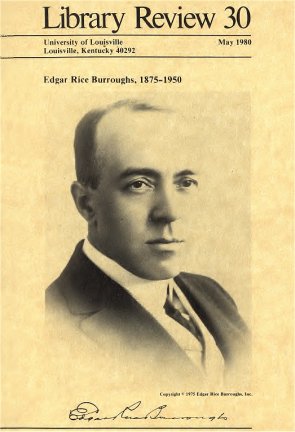

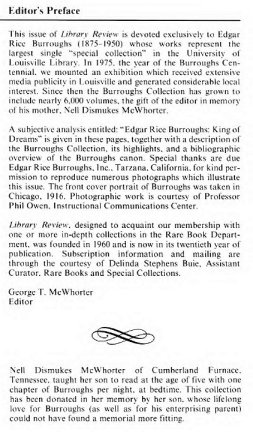

This issue of Library Review is devoted exclusively to

Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950) whose works represent the largest single

"special collection" in the University of Louisville Library. In 1975,

the year of the Burroughs Centennial, we mounted an exhibition which received

extensive media publicity in Louisville and generated considerable local

interest.

Since then the Burroughs Collection has grown to include

nearly 6,000 volumes, the gift of the editor in memory of his mother, Nell

Dismukes McWhorter.

A subjective analysis entitled: "Edgar Rice Burroughs:

King of Dreams" is given in these pages, together with a description

of the Burroughs Collection, its highlights, and a bibliographic overview

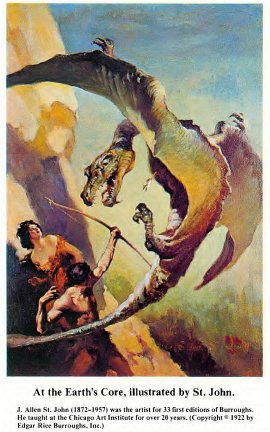

of the Burroughs canon. Special thanks are due Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.,

Tarzana, California, for kind permission to reproduce numerous photographs

which illustrate this issue.

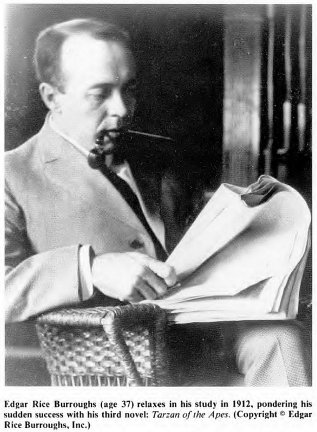

The front cover portrait of Burroughs was taken in Chicago,

1916. Photographic work is courtesy of Professor Phil Owen, Instructional

Communications Center.

Library Review, designed to acquaint our

membership with one or more in-depth collections in the Rare Book Department,

was founded in 1960 and is now in its twentieth vear of publication.

Subscription information and mailing are through the courtesy

of Delinda Stephens Buie. Assistant Curator, Rare Books and Special Collections.

George T. McWhorter

Editor

Nell Dismukes McWhorter of Cumberland Furnace, Tennessee,

taught her son to read at the age of five with one chapter of Burroughs

per night, at bedtime.

This collection has been donated in her memory by her

son, whose lifelong love for Burroughs (as well as for his enterprising

parent) could not have found a memorial more fitting.

1

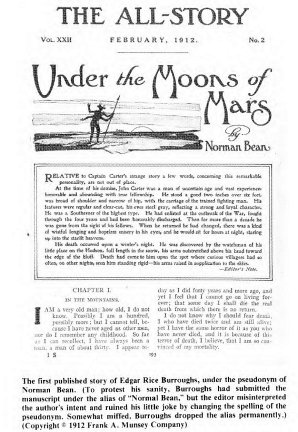

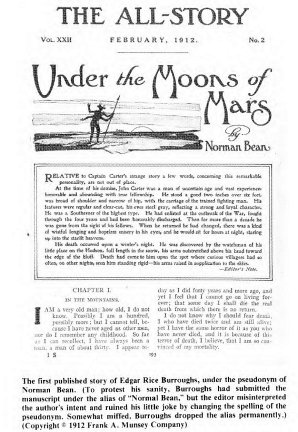

THE ALL-STORY

Vol. XXII ~ February, 1912. ~ No. 2

Under the Moons of Mars

by Norman Bean

Relative

to Captain Carter's strange story a few words, concerning this remarkable

personality, are not out of place.

Relative

to Captain Carter's strange story a few words, concerning this remarkable

personality, are not out of place.

At the time of his demise, John

Carter was a man of uncertain age and vast experience honorable and abounding

with true fellowship. He stood a good two inches over six feet, was broad

of shoulder and narrow of hip, with the carriage of the trained fighting

man.

His features were regular and clear-cut,

his eyes steel gray, reflecting a strange and loyal character. He was a

Southerner of the highest type.

He had re-enlsisted at the outbreak

of the War, fought through the four years and had been honorably discharged.

Then for more than a decade he was gone from the sight of his fellows.

When he returned he had changed,

there was a kind of wistful longing and hopeless misery to his eyes, and

he would sit for hours at night, staring up into the starlit heavens.

His death occurred upon a winter's

night. He was discovered by the watchman of his little place on the Hudson,

full length in the snow, his arms outstretched above his head toward the

edge of the bluff.

Death had come to him upon the spot

where curious villagers had so often, on other nights, seen him standing

rigid -- his arms raised in supplication to the skies.

~ Editor's Note

CHAPTER I: IN THE MOUNTAINS

I am a very old man; how old I do not know. Possibly

I am a hundred, possibly more; but I cannot tell because I have never aged

as other men, nor do I remember any childhood. So far as I can recollect

I have always been a man, a man of about thirty. I appear today as I did

forty years and more ago, and yet I feel that I cannot go on living forever;

that some day I shall die the real death from which there is no

resurrection.

I do not know why I should fear death, I who have died

twice and am still alive; but yet I have the same horror of it as you who

have never died, and it is because of this terror of death, I believe,

that I am so convinced of my mortality.

Read the slightly revised text from the

book release:

HERE

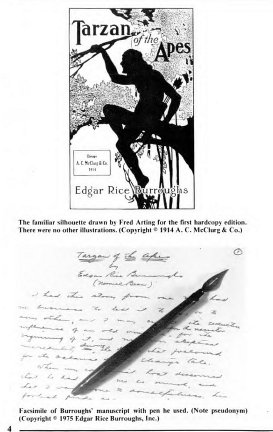

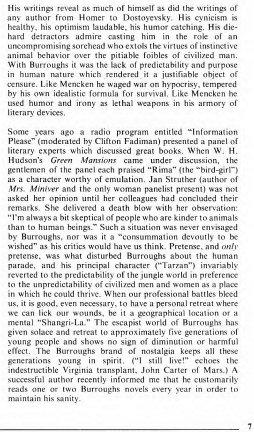

The first published story of Edgar Rice Burroughs,

under the pseudonym of Norman Bean. (To protest his sanity, Burroughs had

submitted the manuscript under the alias of "Normal Bean," but the editor

misinterpreted the authors intent and ruined his little joke by changing

the spelling of the pseudonym. Somewhat miffed. Burroughs dropped the alias

permanently.)

(Copyright © 1912 Frank A. Munsey Company)

Edgar Rice Burroughs: King of Dreams

by George T. McWhorter

Sir

Isaac Newton acknowledged his debt to the past in the oft quoted line:

"If I have seen further it is because I have stood upon the shoulders of

giants." When Edgar Rice Burroughs ( 1875 -1950) was questioned concerning

a similar indebtedness to Jules Verne, H. Rider Haggard. Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle, and H. G. Wells, he admitted that he hadn't read them! He was. himself,

the initiator upon whose shoulders has stood a legion of American science

fiction writers, many of whom have published enthusiastic statements of

their debt to him.

Sir

Isaac Newton acknowledged his debt to the past in the oft quoted line:

"If I have seen further it is because I have stood upon the shoulders of

giants." When Edgar Rice Burroughs ( 1875 -1950) was questioned concerning

a similar indebtedness to Jules Verne, H. Rider Haggard. Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle, and H. G. Wells, he admitted that he hadn't read them! He was. himself,

the initiator upon whose shoulders has stood a legion of American science

fiction writers, many of whom have published enthusiastic statements of

their debt to him.

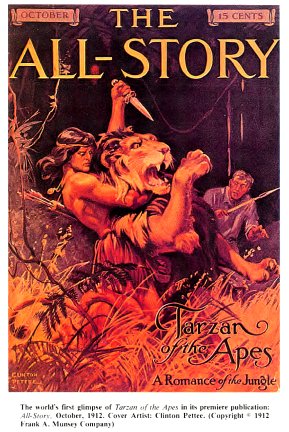

Who was this man who captured the attention of the fiction-reading

world with his very first novel and held it secure for nearly a hundred

more? Gore Vidal writes of him as the "Archetypal American Dreamer" who

had failed at everything he set his hand to until the age of thirty-six.

This included being a drill instructor at a military academy in Michigan,

a gold prospector in Oregon, a rancher in Idaho, a policeman in Salt Lake

City, a salesman in Chicago, and the dabbler in countless get-rich-quick

schemes which fizzled out as his and Emma's expanding family ushered in

. . . an old familiar story.

Many of us are dreamers and escapists, but few are gifted

story tellers in the tradition of a Scheherazade, a Hans Andersen, or an

Edgar Rice Burroughs. The difference between us and them lies in a skillful

blending of' the two worlds we know as "fantastic" and "real." It was as

logical for Burroughs to use his knowledge of military science and tactics

in describing a Martian army as it would be for a CPA to employ his skills

in figuring out your income tax . . . for a fee! (Burroughs' fees resulted

in a multi-million dollar estate which still thrives thirty vears after

his death in Tarzana, California. Aside from Upton Sinclair, he was the

only writer of his time to incorporate himself with a view to publishing

his own books. Unlike Sinclair, he was brilliantly successful.)

It is probably safe to say that a child's mind conceives

of the existential world in terms of black and white, rather than grey

(the "greys" being reserved for experience and introspection). The Burroughs

penchant for creating heroes without blemish and villains who arc totally

execrable has provided continuing fodder for adverse criticism. Yet this

same tendencv lies at the root of his lasting appeal as a writer for, and

shaper of youthful morality. Even in our adult experience it is difficult

to

conceive of anyone we greatly admire as having faults. Likewise, if anyone

has grievously offended us it is difficult to think of him as having redeeming

qualities. So the fantasy world created by Burroughs deals largely in black

and white concepts of good and evil, easily perceived by youngsters yet

infinitely embellished by imaginary situations in exotic locales. The total

effect is that of having roots in the real world while we travel the unexplored

realms of fantasy. Since all of us fantasize on occasion, the sanity of

Burroughs" "Normal Bean" approach anchors us between the two worlds with

a birdVeve view of the best of both.

to

conceive of anyone we greatly admire as having faults. Likewise, if anyone

has grievously offended us it is difficult to think of him as having redeeming

qualities. So the fantasy world created by Burroughs deals largely in black

and white concepts of good and evil, easily perceived by youngsters yet

infinitely embellished by imaginary situations in exotic locales. The total

effect is that of having roots in the real world while we travel the unexplored

realms of fantasy. Since all of us fantasize on occasion, the sanity of

Burroughs" "Normal Bean" approach anchors us between the two worlds with

a birdVeve view of the best of both.

The unexplored universe was his, and his unique fantasies

(in harmonious partnership with his practical knowledge and experience)

took him to the moon, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and beyond. His earthly locales

covered time periods from the Stone Age to Greco-Roman times; from the

Plantagenets to the plains of Western America; to the modernity of Chicago,

Hollywood, Europe, and the Balkans. Lost civilizations in remote jungle

fastnesses, hidden plateaus and extinct volcanos of Africa, Cambodia, Java,

Sumatra, and the Pacific are recurrent themes.

His series of seven novels at the Earth's core, with an

inner sun hanging at perpetual zenith, is a marvel of invention. Lost tribes

of Paulists, Israelites. Crusaders, and Atlanteans come to life in

his limitless vision. Reincarnation, suspended animation, elaborate machines,

and warps in the skein of time transport his cavalcade of heroes to and

from the present to an antediluvian past or a future seen only by himself.

Burroughs was a keen observer of human nature. As previously

noted, he tended to create stereotypes, but in the final analysis they

lend a pleasing credibility to his fast moving plots. They all behave as

expected and the action zips along with new surprises in rapid succession.

One can almost see the author chuckling to himself as he leaves his hero

on the brink of disaster at a chapter's end. to pick up a different thread

of his plot in the ensuing chapter!

It is a device guaranteed to hold one's attention until

the denouement brings all the threads of his spellbinding tapestry together.

With a dreamer's vision (which creates bliss out of torment) his stories

end happily.

Relative

to Captain Carter's strange story a few words, concerning this remarkable

personality, are not out of place.

Relative

to Captain Carter's strange story a few words, concerning this remarkable

personality, are not out of place.

Sir

Isaac Newton acknowledged his debt to the past in the oft quoted line:

"If I have seen further it is because I have stood upon the shoulders of

giants." When Edgar Rice Burroughs ( 1875 -1950) was questioned concerning

a similar indebtedness to Jules Verne, H. Rider Haggard. Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle, and H. G. Wells, he admitted that he hadn't read them! He was. himself,

the initiator upon whose shoulders has stood a legion of American science

fiction writers, many of whom have published enthusiastic statements of

their debt to him.

Sir

Isaac Newton acknowledged his debt to the past in the oft quoted line:

"If I have seen further it is because I have stood upon the shoulders of

giants." When Edgar Rice Burroughs ( 1875 -1950) was questioned concerning

a similar indebtedness to Jules Verne, H. Rider Haggard. Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle, and H. G. Wells, he admitted that he hadn't read them! He was. himself,

the initiator upon whose shoulders has stood a legion of American science

fiction writers, many of whom have published enthusiastic statements of

their debt to him.

His

writings reveal as much of himself as did the writings of any author from

Homer to Dostoyevsky. His cynicism is healthy, his optimism laudable, his

humor catching. His die-hard detractors admire casting him in the role

of an uncompromising sorehead who extols the virtues of instinctive animal

behavior over the pitiable foibles of civilized man. With Burroughs it

was the lack of predictability and purpose in human nature which rendered

it a justifiable object of censure. Like Mencken he waged war on hypocrisy,

tempered by his own idealistic formula for survival. Like Mencken he used

humor and irony as lethal weapons in his armory of literary devices.

His

writings reveal as much of himself as did the writings of any author from

Homer to Dostoyevsky. His cynicism is healthy, his optimism laudable, his

humor catching. His die-hard detractors admire casting him in the role

of an uncompromising sorehead who extols the virtues of instinctive animal

behavior over the pitiable foibles of civilized man. With Burroughs it

was the lack of predictability and purpose in human nature which rendered

it a justifiable object of censure. Like Mencken he waged war on hypocrisy,

tempered by his own idealistic formula for survival. Like Mencken he used

humor and irony as lethal weapons in his armory of literary devices.