Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 10,000 Web Pages in Archive

Presents

Volume 2308

|

ECLECTICA v.2009.02 |

|

|

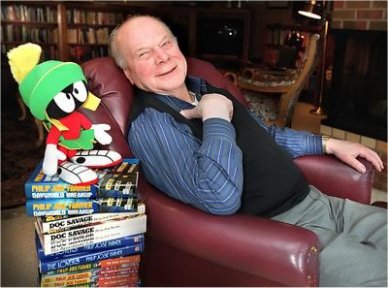

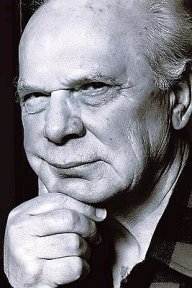

PEORIA ~ February 25, 2009: Science fiction author Philip Jose Farmer died this morning at his home. He was 91.

He was once quoted as saying that, particular in his early career, he had more fans in France, Italy, Germany and Japan than in the United States. Even after he retired from writing, his fans continued to produce “Farmerphile,” a magazine devoted to his life and works. Critics have said that Farmer's influence over the science-fiction community is becoming more apparent over. He was the first author to address adult sexual themes in science-fiction novels. Jonathan Strahan, an editor and critic for Locus magazine, said Farmer treated sex seriously, not in a juvenile manner or for cheap thrills. "It wasn't pornography and it wasn't just about the sex of it. It was about the sexuality of people in an interesting and intelligent way." Joe Lansdale, a critic, writer and friend of Farmer's, credited Farmer with changing the face of science fiction. "I just can't begin to tell you how important he is to the field as well as other fields." Lansdale said Farmer was fearless when it came to the subject matter for his stories. Mr. Farmer did much to carry on the memory and legacy of Edgar Rice Burroughs. In addition to being a dedicated fan and scholar he wrote many stories in the spirit of ERB.  |

|

|

|

|

|

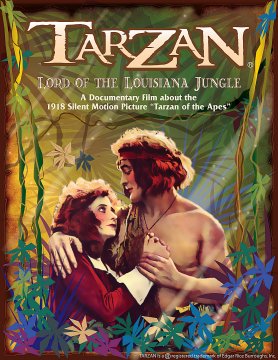

LORD OF THE LOUISIANA JUNGLE Documentary He is planning to attend the 2009 Dum-Dum in Dayton this August. He hopes to bring a camera crew to interview anyone who has any information that would be useful to his project. To date he has been on the Tarzan swamp tour where they shot the film and has interviewed people in Morgan City with knowledge of the filming process. He has heard from many people who are fans of the film. Unfortunately the city archive is very small but they do have a spear that the natives carried. He has also been contacted by a man who owns a boat used in the movie. It was exhibited at the '84 World's Fair and is now in a boat museum in South Louisiana. He is still hoping to meet someone who was in the film over 90 years ago. Al may be contacted at: al@albohl.com

|

Sabre Tooth Tiger Honours Project sculpture on auction at Askart.com |

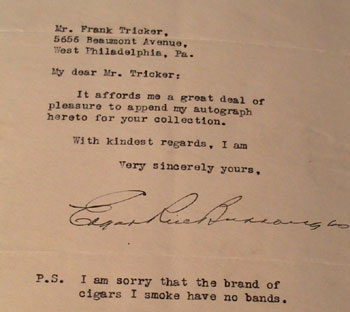

Edgar Rice Burroughs autograph |

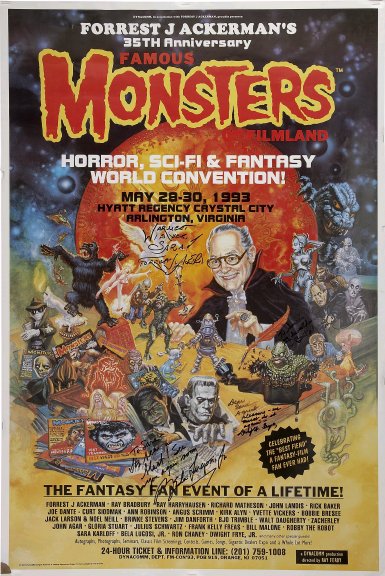

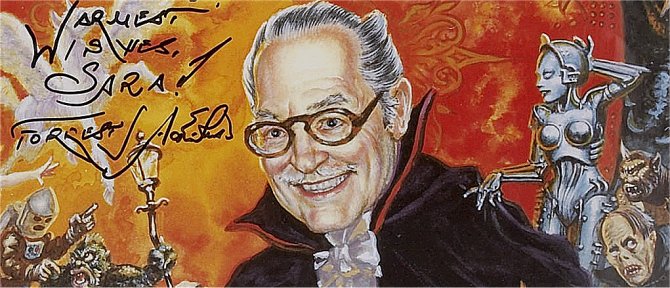

Forrest Ackerman and others signed this Famous Monsters

Convention poster for

the 35th Anniversary Famous Monsters of Filmland Horror,

Sci-Fi & Fantasy World Convention.

It was inscribed and signed to Sara Karloff (daughter

of Boris Karloff) by

"Mr. Science Fiction" Forrest Ackerman, Bela Lugosi

Jr., and Dwight Frye, Jr., son of actor Dwight Frye.

Kala and her balu

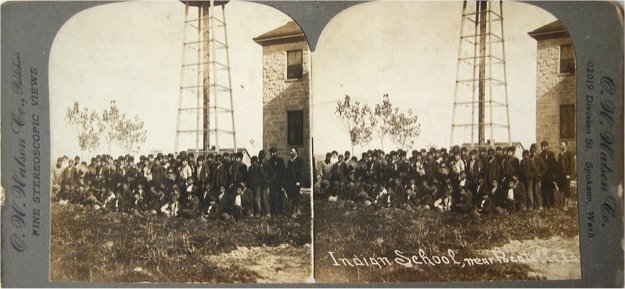

3D Stereoview of 1890s Indian School near Pocatello, Idaho

See links to many more ERB-related stereoviews at

www.hillmanweb.com/brandon

III. BLOG WATCH

FEATURE ARTISTS BLOG

Boris and Julie: Paint and Brush Blog

http://imaginistix.blogspot.com/

Julie and Boris at work

John Carter of Mars sketch commissioned

by Robert Zeuschner

Julie working on a John Carter painting

Commissioned by Bill Niemeyer.

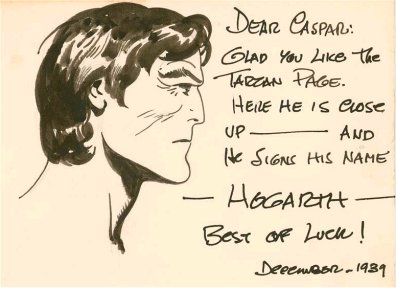

Why doesn’t Tarzan have a beard?

http://entertitlehere.wordpress.com/2009/01/13/why-doesnt-tarzan-have-a-beard/

A totally random question of course, I have several of them supplied by yet another office circular I received via email today. They’ll prove to be excellent little stocking fillers for the blog if I’m feeling uninspired! So Tarzan - beard!? Here’s some theories!No Beards here, just a hairy monkey.

It’s in me Genes mate!Tarzan’s parents were of mixed heritage believe it or not! On white (Caucasian) and the other native American. Apparently native Americans are quite inept at growing facial hair, so one theory is that Tarzan couldn’t grow a beard even if he wanted one!

Watch it pal, I’m armed!

Tarzans dagger often got him out of tough scrapes and boy doesn’t he look manly! No wanting for a Gillette or a barbers, no! Tarzan could shave with his trusty knife!

Jane: She just plain didn’t like facial hair and women wear the shorts in this relationship!

sDid you know?

Tarzan is the son of a British Lord and Lady who were marooned on the West coast of Africa by mutineers

Tarzan means ‘white skin’ (it’s his ape name) his real name was John Clayton.

Tarzan and Jane had a son (see left) Jack

Tarzan has wrestled a dinosaur!

Tarzan could recover from gunshots to the head!

He trained as a soldier in the first world war

He is immune to mental probing (ooh er missus)

And he becomes immortal after drinking a witch doctor’s potion!

Beards [some Pros]Beards are an expression of freedom

A sign of masculinity

Not everyone can own a beard

Shaving is a pain

Beards are bold and daring

Beards are a great disguise

Beards [some Cons]

Beards are itchy

Beards make eating difficult

Beards collect water and take forever to dry

Beards can make you less approachableYour editor sent the answer to this.

Responses to 'Why doesn’t Tarzan have a beard?' From Bill Hillman

"Read the books"

http://www.erbzine.com/craft/

Tarzan saw pictures of Englishmen in the books in his dead parents’ cabin. He knew he was different from the apes and wanted to be a man. He shaved off his whiskers with his father’s hunting knife using the reflection in a jungle pool

Bill Hillman

Editor and Webmaster for the

Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Websites and Webzines

http://www.ERBzine.com

http://www.tarzan.com

http://www.tarzan.org

http://www.DantonBurroughs.com

http://www.johncolemanburroughs.com

http://www.pellucidar.org

http://www.johncarterofmars.ca

http://www.tarzana.ca

http://www.edgarriceburroughs.caBill Hillman

13 Jan 09 at 4:41 pm

Bill thanks for your comments and all those links but please understand that this was ‘tongue in cheek’ article. FYI, 90% of the ‘did you know’ stuff was from wiki and the rest was my imaginationTarzan.com is well worth a visit people - lots of useful information!

Library Journal’s Most Influential Fiction of the 20th Century

December 28th, 2008

http://readthink.edublogs.org/2008/12/28/library-journals-most-influential-fiction-of-the-20th-century/85 Edgar Rice Burroughs Tarzan of the Apes 1914

1 Harper Lee To Kill a Mockingbird 1960

3 J.R.R. Tolkien Lord of the Rings 1956

7 George Orwell Nineteen Eighty Four 1949

8 George Orwell Animal Farm 1954

9 William Golding Lord of the Flies 1954

18 Ray Bradbury Fahrenheit 451 1952

22 J.R.R. Tolkien The Hobbit 1937

36 Margaret Atwood The Handmaid’s Tale 1986

40 Robert A. Heinlein Stranger in a Strange Land1961

41 Aldous Huxley Brave New World 1932

58 Anthony Burgess A Clockwork Orange 1962

62 L. Frank Baum The Wonderful Wizard of Oz 1900

63 C.S. Lewis The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe 1950

64 A. Conan Doyle The Hound of the Baskervilles 1902

67 Jack London The Call of the Wild 1903

69 Marlon Zimmer Bradley The Mists of Avalon 1983

76 Arthur C. Clarke 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968

115 Frank Herbert Dune 19652008 seemed a particularly rewarding year of reading for me, to a large part due to the way the year started out—with a mega-dose of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Of the twenty-three books I read (I didn’t say I guzzled books; I tend to sip and savor), the first six were by ERB.

IV. BOOKS BOOKS BOOKS

FANTASY BOOK CRITIC

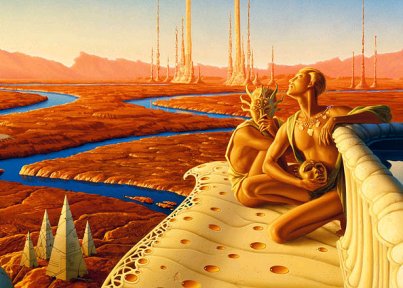

2008 FAVORITES (In which I lavish much praise, but get uncharacteristically bitchy, too):1) “A Princess of Mars”. The first in Burroughs’ tales of John Carter, Warlord of Barsoom. I bought nearly the entire series back in the seventies, but it wasn’t until this year that I completed it, and finally read the novel that started it all.

2) “The Master Mind of Mars” focuses, as most the novels do, actually, on a hero other than John Carter himself (these near-naked swashbucklers tending to be rather interchangeable, as are the princesses whose rescue is their full-time job—though that doesn’t stop the reader from yearning for those exotic beauties along with the heroes). This novel, like the earlier The Gods of Mars, takes a scathing look at religion. Burroughs didn’t seem to work much sub-text or social commentary into his breathlessly exciting pulp adventures, but these two delighted me with some of the most biting satire of religion I have ever encountered, and hence are two of my favorites in the series.

3) “John Carter of Mars” actually consists of two stories, the titular novella and “Skeleton Men of Jupiter.” The latter—and last of the Barsoom stories, though never finished—holds up perfectly well against the series, but the first story . . . well, here I’d like to introduce something I call the “What the Fuck” factor. Many, if not most, novels have a WTF factor. And before you say it, yes, I’m sure one could find plenty of WTF moments in my own stories. A good example of a WTF moment can be found in Stephen King’s collection Everything’s Eventual, in the story “Autopsy Room Four.” Page 23 of the paperback starts out with a memory of a past incident, and maybe this is what throws King off for the next five or six paragraphs, in which the first person/present tense narrative slips into past tense. (The editors of Robert Bloch’s Psychos, in which it originally appeared, and at Pocket Books couldn’t catch this, or were they too timid to copyedit the King?).

Anyway, “John Carter of Mars” merits a resounding WTF. Apparently it was co-written with his son as a children’s book, and that might excuse the substandard writing, but what really spun my head was how wrong so much of it was, in terms of the technology, animals, and so on that we are so well acquainted with from the series. Why would ERB’s son have been less familiar with his father’s world, and how could ERB have truly had anything to do with this thing? A big disappointment, but it hardly takes away from the fun and wonder and rich imagination of all the other books that precede it. More a curiosity item, really.

4) “Escape on Venus”. Having exhausted Mars, I moved onto another ERB book I bought in the seventies but never finished. It’s just as entertaining, just as imaginative as the Barsoom tales, and I’ll have to look into more books in the series. WTF factor: The novel is told in the first person by the protagonist, Carson Napier, but for several chapters switches to third person so that we might follow the heroine Duare. But I’m not complaining, really, as this part of the book—including a battle between two bloodthirsty beasts and the death of Duare’s captor, an ameba-like humanoid who dies horribly in a weirdly ecstatic, though futile effort to divide himself—includes some of its best sequences.

5) “The Mood Maid”. More ravishing beauties and heinous villains, but this time on our own satellite.

6) “The Moon Men”. This edition actually consisted of the two sequels to “The Moon Maid”, these being the very bleak and depressing “The Moon Men”—detailing the occupation and subjugation of Earth by brutish, Nazi-like lunar folk—and “The Red Hawk”, in which the scattered tribes of Earth, resembling bands of Native Americans of old, rebel against their vile masters. The first novel in the trilogy is the most like a Barsoom book, and thus the most fun, but the more solemn sequels have their own merits.

Conversations with Carl Sagan (2006)"Then, when I was ten -- I was at P.S. 101 in Brooklyn at the time -- I came upon the Edgar Rice Burroughs novels about John Carter and his travels on Lowell’s Mars. It was a world of ruined cities, planet-girdling canals, immense pumping stations -- a feudal technological society. The people there were red, green, black, yellow, or white and some of them had removable heads, but basically there were human. I didn’t realize then the chauvinism of making people on another planet like us; I simply devoured what seemed to me the riches of another planet’s biology. Carter fell in love with a princess of the Kingdom of Helium, Dejah Thoris. It was very exciting, and I loved those books. They were full of new ideas. On Burroughs’s Mars, there were two primary colors more than on Earth, and I would close my eyes and try to imagine them. I tried to imagine my way to Mars, the way Carter did: I would go into a vacant lot, spread my arms, and wish to be on Mars."

Thirty-one years later, Sagan taped up on the wall outside his Cornell office a map of Mars as Burroughs portrayed it, with Xs marking the spots where Carter landed. He even showed visitor, on a globe of Mars made from Mariner 9 photographs, exactly where Carter would have come down.

"Many an evening I spent in vacant lots, arms outstretched, thinking myself to that twinkling red place, but nothing happened. I tried all different kinds of wishing. Suddenly, it dawned on me that this was fiction; maybe there was some better way to get to Mars."

On Tarzan by Alex Vernon The cover art for Alex Vernon's slim cultural biography "On Tarzan" is a photo of winding green tendrils and vines, vines being the equivalent of the cross-town bus for the Lord of the Apes. But the photo is also a warning of the thicket we are about to enter: a rampant, root-bound tangle of a book in which the author muses upon Tarzan as, among other things, a kind of prefiguring Colossus of American modernity, a Leopold Bloom in a loincloth.

Review by Dan Neil - LA Times

January 15, 2009In Vernon's gaze, Edgar Rice Burroughs' Ape Man is the most protean character since . . . well . . . Proteus, both a product of 19th century literary naturalism and a rejection of that naturalism. Here, Tarzan is a tonic to the creeping emasculation of urbanism (cf., Prufrock); there, he's a homoerotic analogue, a smooth-skinned catamite in a leopard singlet (cf., Village People).

What's jungle-speak for "whiplash"?

Everywhere, Tarzan epitomizes Americanism -- never mind that he was born to English nobility. In Vernon's view, Tarzan is Horatio Alger wrestling with a crocodile. He is an immigrant, a dual citizen, an orphan, an adolescent, a language refugee: all states of being that roughly correspond to the fresh-off-the-boat culture of early 20th century America. (Burroughs' first Tarzan story appeared in 1912.) But wait, there's more. Tarzan is an avatar of both nature and nurture, Rousseau and B.F. Skinner, of Haeckel's ontology-phylogeny recapitulation theory, of post-racial harmony and violent white neocolonialism. Writes Vernon: "The Tarzan tales' argument for inherent and essential gender and racial roles and traits self-deconstructs. Cultural relativism rears." Uh-huh. Sure it does.

No one enjoys an overdetermined cultural analysis more than I do, and to his credit, Vernon cheerfully acknowledges that the vine from which he's swinging can't always bear the weight. "Sometimes I want to throw up my hands and say: None of the above," he writes. "[Tarzan is] just an escapist action hero. Readers and viewers lose themselves in Tarzania, and wallow in their lostness." But then it's back to the library stacks for more research. This 177-page book is appended with 22 pages of notes, a bibliography and an index. Even its title is preciously, even hilariously academic.

In fairness, Vernon is a pretty lively writer and "On Tarzan" is full of fun facts. The first movie Tarzan, for instance, was Elmo Lincoln, a former Arkansas state trooper who also played in D.W. Griffith's "Birth of a Nation." A dire hint of that Ku Klux Klan saga is seen in the 1918 "Tarzan of the Apes" when Tarzan uses a vine-fashioned noose to lynch unruly natives. OK, that's not a fun fact. How about this? Lincoln was so hairy that he had to be shaved twice a day during shooting.

Modern readers have lost touch with Tarzan, whom Vernon calls -- defensibly if not definitively -- the most popular fictional character of the 20th century. From 1918 to 1970, Hollywood churned out 43 Tarzan features (and a bazillion knockoffs). There were uncountable comic strips, illustrated novels, radio and television shows and a mighty slew of "notebooks, wallets, several games, stickers, playing cards, stamps . . . knapsacks, beach balls and thongs."

Let's stop a moment to savor the notion of Tarzan thongs, shall we? There were Tarzan clubs throughout America and, of course, Southern Californians know that Tarzana was built around property once owned by Burroughs' Tarzana Ranch.Vernon's naked American avatar was so beloved around the world that, when Johnny Weissmuller died in 1984, the Soviets played his Tarzan yell in Red Square for 24 hours straight.

And yet, Tarzan was obviously an agent of cultural imperialism, a propaganda tool, an interventionist, a racist; the movies were banned from Egypt to Cuba on grounds of political incorrectness. The men who took the U.S. into Vietnam "were a troop of Tarzans," Vernon writes. "A man of supreme surety, Tarzan on page and screen is never wrong, he knows he's never wrong and we forgive and forget his arrogance because he always proves himself -- and because, if we're Americans, he's one of us."

For all that, Tarzan could also be seen as a revolutionary figure, not a gorilla but a guerrilla, resisting the evil white man's intrusion into Eden. The tree-dweller preaches anti-materialism. "His association with apes defied the racist, classist assumptions of the day," notes Vernon. Tarzan is Joe Sixpack with a six-pack. But what's most telling, perhaps, is that Tarzan fell off the mythical map after about 1970. The few Tarzan films that have appeared since then have set the character in the simplified frame of romantic adventure -- a la the Bo Derek vehicle "Tarzan: The Ape Man" (1981) -- or cast him as muscle-bound knucklehead.

Disney's "Tarzan: the Broadway Musical" flopped in 2007, as did the animated movie before it. At a time when Hollywood is resurrecting superheroes from Batman to Captain Marvel, a Tarzan reboot is almost unthinkable.Vernon draws the unexceptional conclusion that Tarzan's demise is linked to our growing unease with neocolonialism, which is to say, depictions of a white man ruling, often brutally, over dark-skinned indigenous peoples. In the movies, Africans -- infrequently played by black actors and extras, by the way -- are invariably depicted as childish, god-haunted savages.

At the same time, Vernon suggests that Tarzan's brand of steady masculinity couldn't survive the age of irony. The rise of environmental consciousness has also tended to make audiences less comfortable with Tarzan's remorseless, lion-stabbing dominion over paradise. (In the early movies, Elmo Lincoln actually killed drugged-up lions.) For all these reasons, or none of them, Tarzan has wound up on the scrap heap with other defunct American heroes, from Natty Bumppo to Popeye the Sailor Man. The holler heard round the world is no more.

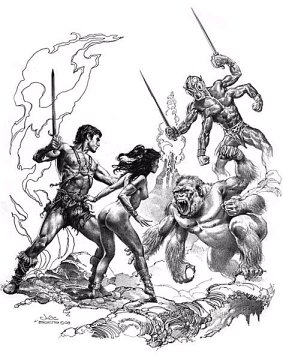

The Outlaws of Mars (Trade Paperback)

by Otis Adelbert Kline, with an introduction by Joe R. Lansdale

Paizo Publishing, LLC ~ $12.99Otis Adelbert Kline’s final triumphant sword-and-planet epic roars back into print for the first time in almost 50 years! Jerry Morgan accepts his scientist uncle’s offer to transport him to Mars for a series of thrilling adventures and exploits featuring terrible monsters, fantastic societies, and gorgeous princesses in the Edgar Rice Burroughs tradition.

At last presented in the original, unabridged format last seen in 1934’s Argosy Weekly, the new Planet Stories edition of this science fiction classic restores Kline to his place of honor in the sword and planet field. A charming introduction by Joe R. Lansdale (“Bubba Hotep,” The Bottoms) puts the novel into a modern context for readers unfamiliar with Kline’s legacy.

304-page softcover trade paperback

ISBN-13: 978-1-60125-151-0

Art by Michael Whelan My Mars National Geographic: October 2008

By Ray Bradbury

When I was six years old I moved to Tucson, Arizona, and lived on Lowell Avenue, little realizing I was on an avenue that led to Mars. It was named for the great astronomer Percival Lowell, who took fantastic photographs of the planet that promised a spacefaring future to children like myself.Along the way to growing up, I read Edgar Rice Burroughs and loved his Martian books, and followed the instructions of his Mars pioneer John Carter, who told me, when I was 12, that it was simple: If I wanted to follow the avenue of Lowell and go to the stars, I needed to go out on the summer night lawn, lift my arms, stare at the planet Mars, and say, "Take me home."

That was the day that Mars took me home—and I never really came back. I began writing on a toy typewriter. I couldn't afford to buy all the Martian books I wanted, so I wrote the sequels myself. More>>>

Visions of Mars

Robot explorers transform a distant object of wonder into intimate terrain.

By John Updike

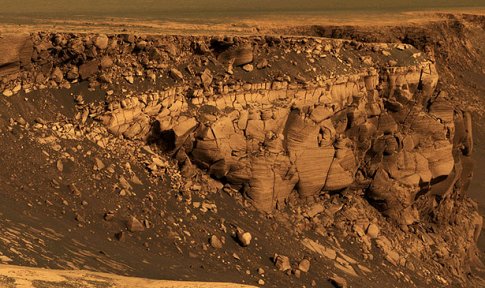

Photograph by NASA/JPL/Cornell University

National Geographic ~ December 2008

Reminiscent of earthly wilderness, hinting at Earthlike geology,

the jagged rim of Victoria Crater appears in a near true-color image taken by the rover OpportunitMars has long exerted a pull on the human imagination.The erratically moving red star in the sky was seen as sinister or violent by the ancients: The Greeks identified it with Ares, the god of war; the Babylonians named it after Nergal, god of the underworld. To the ancient Chinese, it was Ying-huo, the fire planet. Even after Copernicus proposed, in 1543, that the sun and not the Earth was the center of the local cosmos, the eccentricity of Mars's celestial motions continued as a puzzle until, in 1609, Johannes Kepler analyzed all the planetary orbits as ellipses, with the sun at one focus.

In that same year Galileo first observed Mars through a telescope. By the mid-17th century, telescopes had improved enough to make visible the seasonally growing and shrinking polar ice caps on Mars, and features such as Syrtis Major, a dark patch thought to be a shallow sea. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini was able to observe certain features accurately enough to calculate the planet's rotation. The Martian day, he concluded, was forty minutes longer than our twenty-four hours; he was only three minutes off. While Venus, a closer and larger planetary neighbor, presented an impenetrable cloud cover, Mars showed a surface enough like Earth's to invite speculation about its habitation by life-forms.

Increasingly refined telescopes, challenged by the blurring effect of our own planet's thick and dynamic atmosphere, made possible ever more detailed maps of Mars, specifying seas and even marshes where seasonal variations in presumed vegetation came and went with the fluctuating ice caps. One of the keenest eyed cartographers of the planet was Giovanni Schiaparelli, who employed the Italian word canali for perceived linear connections between presumed bodies of water. The word could have been translated as "channels," but "canals" caught the imagination of the public and in particular that of Percival Lowell, a rich Boston Brahmin who in 1893 took up the cause of the canals as artifacts of a Martian civilization. As an astronomer, Lowell was an amateur and an enthusiast but not a crank. He built his own observatory on a mesa near Flagstaff, Arizona, more than 7,000 feet high and, in his own words, "far from the smoke of men"; his drawings of Mars were regarded as superior to Schiaparelli's even by astronomers hostile to the Bostonian's theories. Lowell proposed that Mars was a dying planet whose highly intelligent inhabitants were combating the increasing desiccation of their globe with a system of irrigation canals that distributed and conserved the dwindling water stored in the polar caps.

This vision, along with Lowell's stern Darwinism, was dramatized by H. G. Wells in one of science fiction's classics, The War of the Worlds (1898). The Earth-invading Martians, though hideous to behold and merciless in action, are allowed a dollop of dispassionate human sympathy. Employing advanced instruments and intelligences honed by "the immediate pressure of necessity," they enviously gaze across space at "our own warmer planet, green with vegetation and grey with water, with a cloudy atmosphere eloquent of fertility, with glimpses through its drifting cloud wisps of broad stretches of populous country and narrow, navy-crowded seas."

In the coming half century of Martian fancy, our neighboring planet served as a shadowy twin onto which earthly concerns, anxieties, and debates were projected. Such burning contemporary issues as colonialism, collectivism, and industrial depletion of natural resources found ample room for exposition in various Martian utopias. A minor vein of science fiction showed Mars as the site, more or less, of a Christian afterlife; C. S. Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet (1938) invented an unfallen world, Malacandra. Edgar Rice Burroughs's wildly popular series of Martian romances presented the dying planet as a rugged, racially diverse frontier where, in the words of its Earthling superhero John Carter, life is "a hard and pitiless struggle for existence." Following Burroughs, pulp science fiction, brushing aside possible anatomical differences, frequently mated Earthlings and Martians, the Martian usually the maiden in the match, and the male a virile Aryan aggressor from our own tough planet. The etiolated, brown-skinned, yellow-eyed Martians of Ray Bradbury's poetic and despairing The Martian Chronicles (1950) vanish under the coarse despoilment that human invasion has brought.

But all the fanciful Martian megafauna—Wells's leathery amalgams of tentacles and hugely evolved heads; American journalist Garrett Serviss's 15-foot-tall quasi red men; Burroughs's 10-foot, 4-armed, olive-skinned Tharks; Lewis's beaver-like hrossa and technically skilled pfifltriggi; and the "polar bear-sized creatures" that Carl Sagan imagined to be possibly roaming the brutally cold Martian surface—were swept into oblivion by the flyby photographs taken by Mariner 4 on July 14, 1965, from 6,000 miles away. The portion of Mars caught on an early digital camera showed no canals, no cities, no water, and no erosion or weathering. Mars more resembled the moon than the Earth. The pristine craters suggested that surface conditions had not changed in more than three billion years. The dying planet had been long dead.

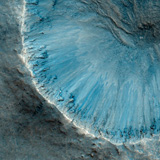

Mars Interactive Timeline

Mars

Victoria Crater

Young Crater

V. EVENTS

|

Defining moment: Charles Atlas brings muscles to the

masses, February 1929

Ref: FT Magazine When Charles Atlas won the “world’s most perfectly developed man” contest at Madison Square Garden, New York, in 1923, the promoter, Bernarr Macfadden, decided it had to be the last such event. Atlas had also triumphed the previous year, and Macfadden was a realist: “What’s the use of holding them?” he said. “Atlas will win every time.” The competition prize was either a screen test for a Tarzan film or $1,000. Atlas took the money and used it to set up a mail-order company to sell the secrets of his training routine – unlike other bodybuilders, the strongman chose not to lift weights, preferring an isometric technique that he had devised after watching a tiger stretching at the zoo (“Did you ever see a tiger with a barbell?” he liked to ask). |

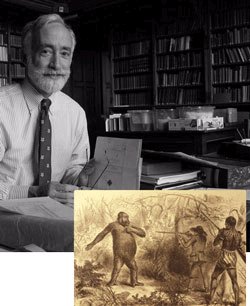

Robert McCracken Peck Event at the Yale Peabody Museum

The “Discovery” of the Gorilla and How It Shook the World

February 12, 2009

|

Du Chaillu confronting a gorilla in W. Africa |

|

In 1859, the very year Charles Darwin first published On the Origin of Species, a young French–American explorer named Paul Du Chaillu emerged from the jungles of Gabon, West Africa, with breathtaking accounts of large, ferocious primates. While the gorilla had been described scientifically in 1847, Du Chaillu provided the western world with the first descriptions of living gorillas in the wild.

In this fully illustrated lecture, naturalist and historian Robert McCracken Peck, Senior Fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and author of The 'Discovery' of the Gorilla and How It Shook the World, will tell the fascinating story of the flamboyant and enigmatic Du Chaillu and the evolutionary firestorm his “discovery” ignited, tracing its enormous social repercussions from the 19th century to today. Peck will examine the explorer’s influence on Edgar Rice Burroughs (the creator of Tarzan), the propaganda campaigns of the First World War, and the making of the 1933 film King Kong and its later versions.

YALE CELEBRATES DARWIN: Talk on the Discovery of the Gorilla Featured as Part of Darwin Bicentennial Celebration

http://opa.yale.edu/sp/darwin/

http://opa.yale.edu/news/article.aspx?id=6392

Paul Du Chaillu's Lost In The Jungle

was part of ERB's Personal Library

Read our Paul Du Chaillu Features in

ERBzine 0872

ERBzine 0872a

ERBzine 0872m

VI. VIDEOS

|

Video at YouTube |

From

Tarzana.ca

The

Fantastic Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() WEBJED:

BILL HILLMAN

WEBJED:

BILL HILLMAN![]()

Bill

and Sue-On Hillman Eclectic Studio

Some

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2009/2011/2022 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.