Volume 1865

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/unknown.htm

| Chapter I. | An Ocean Voyage. |

| Chapter II. | In the Belfry of St. Lorenzo |

| Chapter III. | In the Crater of Vesuvius |

| Chapter IV. | You Have Saved my Life |

| Chapter V. | At Penang |

| Chapter VI. | Strange Surroundings |

| Chapter VII. | Good-by Jack |

| Chapter VIII. | Bangkok |

| Chapter IX. | Pat's Courage |

| Chapter X. | Urka the Dwarf |

| Chapters XI - XXI Continued in Part II | |

| Chapter XI. | The White Bellies |

| Chapter XII. | A New Enemy |

| Chapter XIII. | The Sand Storm |

| Chapter XIV. | The Bastinado |

| Chapter XV. | The Reflection in the Mirror |

| Chapter XVI. | The Forest Village |

| Chapter XVII. | The Eveless Eden |

| Chapter XVIII. | Crying Out for Death |

| Chapter XIX. | The Missing Link |

| Chapter XX. | A Slave Sale |

| Chapter XXI. | Conclusion |

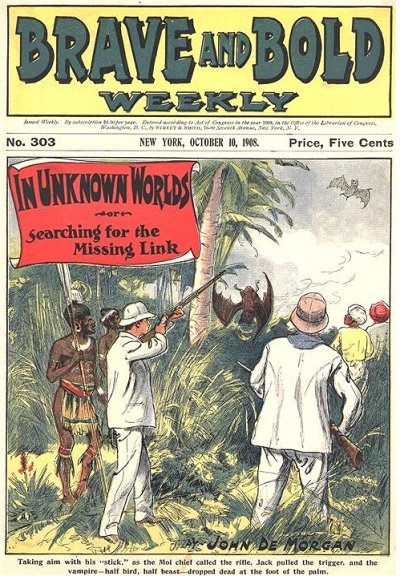

Unknown Worlds;

or, The Search for the Missing Link"Am I dreaming?" Chapter I

"Guess not. To judge from the hearty dinner you have just eaten, I should say you ought to be very much awake."

"But, Walter, it seems too good to be true."

"Does it?"

"Yes; I can scarcely realize it. No, I cannot realize it at all."

"I realized that you were awfully sick for four days, and I wondered whether you would ever get over it."

"I did not want to."

"That is what they all say."

"Were you never seasick?"

"No."

"And you have crossed three or four times."

"Yes, I have seen a bit of the world, and intend seeing a great deal more before I die, that is, if I live long enough."

"What made you think of me?"

"I'll tell you just how it was, Jack. I always liked you better than any other member of my beloved family and

I came home and found that you had to give up the idea of going to college because of your sickness, I asked the doctor what would be the best thing to make a man of you.

"And he said?"

"Travel."

"I always did want to travel."

"So I took his prescription and --- here you are."

"But it's an awful expense to you."

"No, it isn't. I fixed all that. You know I am traveling for my paper, but I have also a commission from the French Geographical Society, and the members pay your expenses."

"You don't mean --- "

"I mean that you are engaged by the most learned society as an explorer, and you have a name to make."

"I never thought I should become an explorer --- "

"I didn't yesterday, or the day before."

"It was stormy --- now, wasn't it?"

"Yes, Jack, it was a little rough."

"A little! Why, I thought the steamer would have gone down, and I hoped it would."

"You were not the only one."

"No, I suppose not."

"It was funny. There was that stout old party, you know, the one who sat opposite to you at dinner. Well on the second day out he was trying to cross the saloon, when the steamer gave a lurch, and he tried hard to stand on his head. But that was not as ludicrous as the antics of young Westerleigh --- "

"That dude?"

"Yes; he was dressed to kill, and was boasting that he never was sick. He was on deck, and insisted on talking to the men who were washing the deck. One man trundled his mop and splashed Westerleigh all over; it was his own fault, for he knew the risk. He turned suddenly, and the ship rolled rather heavily at the same time, causing him to sit down in a pail of water --- ; and dirty water it was, too --- with such force that, when he was helped to his feet, the pail adhered to him and he was unable to straighten himself."

"It must have been funny."

"So it was; and when you rolled off your berth and asked me to throw you overboard, that was funny also; but you are all right now, Jack; and if you go on eating as you did at dinner, the company won't gain by your sickness, for you will more than make up.

"I feel so empty my stomach was just an aching void."

"I should say it was, for you unloaded enough for a dozen of your size: But I guess they see land."

The passengers were crowding forward, on the deck of the great Atlantic steamer, and Walter followed them, with Jack leaning on his arm.

"Yes, it's Gibraltar," Walter said, after looking through his marine-glass. "Gibraltar! Let me see it. I never saw a larger fort than Wadsworth and Hamilton, and they must be small by comparison with Gibraltar."

"They're not in it," answered Walter, falling into slang.

"Do we stop at Gibraltar?"

"No. We have no time for such a thing. Don't you know we carry the United States mail to Genoa?"

Walter Endicott was a New Englander.

His name proclaimed that fact, and he was rather proud of it, especially when any one asked if he was of the same family as Governor John Endicott, the stern old Puritan governor of Massachusetts in the seventeenth century.

"He was my paternal ancestor," answered Walter proudly.

Walter was not governor of the Bay State, for the title does not descend hereditarily, but was a very excellent newspaper correspondent, who had, by his journeyings and correspondence, made his paper an authority on exploration and geographical discoveries.

His writings had attracted the attention of European governments, and France, having an eye on extending its Asiatic colonies, commissioned him to explore Cochin China, or, more properly, the Kingdom of Anam.

As Waiter knew that his paper would pay all his expenses, he arranged to take his younger brother, John, with him, and, as he had put it, let John represent the French Geographical Society, which really meant the French Government.

John Endicott had left his home in Boston when quite young; and had lived with his aunt, good, old, Puritan Kezia Endicott, in New York.

The Endicott family was a large one, and, therefore, quite willing that one of its members should be a New Yorker.

John had distinguished himself at school, but had studied too diligently, and, in consequence, was too weak and sickly to enter Columbia College, as he had wished.

While bemoaning his sad, fate, his brother, Walter, landed in New York from Japan, only to find the new offer to explore Indo-China, the land of mystery and wonders.

He made a flying visit to Boston, arranged to take Jack with him on his tour, secured his outfit, and as we have seen, was again on his way to the peculiar lands known only by name to the majority.

Before they had been long in the beautiful blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea they all wished the voyage was only just beginning, instead of approaching its termination.

"Oh, how lovely!" exclaimed Jack, as a little later he caught sight of Genoa.

The exclamation was warranted, for the city from the sea is really most beautiful, rising as it does out of the sea in a broad semicircle, and dotted about with the mansions and palaces of the wealthy, with churches and public buildings relieved here and there with carefully terraced gardens and groves of orange and lemon-trees, making it justly entitled to the epithet of "The Superb."

"I do love old cities," exclaimed Beatrice Gregory, a young lady passenger who had never seen an old city in her life until she caught a glimpse of Genoa.

Jack was just as enthusiastic, but then, he was just at the age when poetic enthusiasm fills the soul.

He was eighteen, while his brother was twelve years his senior.

"How long shall we stay in Genoa?" asked Jack.

"A few days at most, and then, we go to Naples."

"To Naples! I am so glad; I am going there also," Beatrice Gregory remarked. "As soon as we go?" asked Walter, half-hoping she would say yes.

"I shall certainly hope to be able to leave at the same time; that is, if I shall not bore you."

"Will Mrs. Cottrell fall in with your ideas?" asked Walter.

"Amy Cottrell travels with me because I wish it, and my wishes are always hers." Genoa was reached; and all was confusion and bustle.

Passengers got in each other's way, and fell over each other in their fussy anxiety to be ready to land.

The mixed nationalities on the dock, the babel of languages, the peculiar variety of costumes, made the scene picturesque, and added a charm which raised the enthusiasm of the people from the Western world to fever heat.

Beatrice Gregory was a thorough child of nature. She was American, and that means much in the Old World. Chapter II

She was very quickly "chummy" with Jack.

They were comrades, and talked as freely as though they had known each other all their lives instead of a few days.

On the afternoon of the day following the arrival in Genoa, the four --- Mrs. Cottrell, Beatrice Gregory, Walter and Jack Endicott --- entered the grand old Cathedral of Lorenzo, so rich in its art- treasures.

Amy Cottrell and Walter in some way became separated from Jack and Beatrice. Jack never once thought of his brother, he was so filled with enthusiasm and poetry.

The statues, paintings, stained glass windows, massive pillars and gorgeous altar-pieces were examined with care, and both Beatrice and Jack were in raptures.

Then they started up the old steps of the ancient tower and explored the belfry thoroughly.

There were twelve bells, one for each of the apostles, and as the guide-book told them, there was an inscription on each bell and another on the clapper.

There was one bell, the inscription of which had not been read in modern times; and no one could tell what it was.

"I wonder some one has not climbed up to read it," said Beatrice.

"Yes; it would be easy enough."

"I wonder which bell it is?"

"The guide-book says the one named after the apostle who succeeded Judas Iscariot.

"Let us see if we can find it."

The two young people examined each bell and traced out the names until only one remained.

They knew that was the one of which they were in search.

It was the highest of all, and hung over the great well formed by the winding stairs.

"You see, it is not so easy," said Beatrice, with a shudder.

"Why not?"

"It is so dangerous."

"Just so; but, Beatrice, I am going to read that inscription."

"How?"

"I am going to climb up the rope."

"Don't."

"Why?"

"You might fall."

"I might, but it is not likely."

"If you did?"

"If I did I should never know anything about it."

"Please don't."

"Do you remember that day we passed Gibraltar, when I climbed up the rigging, and even the captain said he had never seen anyone do it, better."

"Of course, I remember, and you did frighten me."

"I am going to do it, so don't hinder me. I will set the good folks of Genoa at their ease by telling them what words are engraved on the bell."

Beatrice secretly admired Jack's daring, though she hoped he would not attempt the exploit.

The bells were hung as fixtures, being too heavy to swing.

The clapper, or hammer, was on the outside of the bell, and could easily be worked by the long rope, which reached through four lofty stories to the ground floor.

Jack saw that by pulling the rope it raised the hammer ready for striking. It was necessary to raise it and secure the rope tightly, so that it couldn't release the hammer and strike the bell.

He drew the rope toward him until the hammer was raised as high as it would go, then he tied it very securely to the iron rail which surrounded the well.

For a moment he thought the risk too great, but he remembered that he had once boasted to Beatrice that an Endicott never broke his word, and he had said he would climb the rope.

It would have been much easier had the rope hung down perpendicularly, but it slanted somewhat on account of being secured to the rail.

"Don't go, Jack."

"Think of the fame, Beatrice."

She said no more, but watched the daring climber.

Up he went, not daring to look down, and yet afraid to look up at the bell.

Higher and yet higher he went, until he seemed lost in the distance.

He had reached the clapper, but the bell was farther away than he had imagined.

To give the right tone to the bell, the clapper, which weighed two hundred pounds, had to swing several feet.

He had thought of that when he started, and it was humiliating to descend without reading the inscription.

He reached the beam from which the hammer was suspended and sat astride it to rest and think.

Three hundred feet below was the hard, marble floor, above him a seemingly endless labyrinth of beams and cross-pieces.

He was level with the top of the bell, but several feet away.

Beatrice dare not look up at him. She sat down, and, with her face buried in her hands, prayed that Jack might descend in safety.

Jack had forgotten her. He only thought of the rash enterprise in which he was engaged.

He moved cautiously along the beam until he could touch the great chain which supported the bell.

Grasping it tightly, he lowered himself until his feet rested on the top of the bell. As he touched the bell several birds, which had made their homes in the belfry, flew past him and nearly caused him to lose his balance.

The perspiration poured from every pore, his nerves were giving way, and only by a tremendous effort of will could he retain his footing. Every second was like an hour, and yet he dare not hurry.

When he had calmed his nerves a little he stooped down to find the inscription.

He looked all over the upper part of the bell, and satisfied himself that there was no inscription there.

"Fooled!" he muttered. "Risked my life for nothing!"

He must descend.

What proof could he ever give that he had been up there?

Only his own word, corroborated by Beatrice.

Who would accept such testimony?

Besides, Beatrice would not be with him long; and when he told, in future years of his daring, he would be looked upon as a Yankee yarn-spinner, and his story would be classed with other freaks of a vivid imagination.

He groaned as he realized the failure of his enterprise. It was necessary to descend at once, for the hour was getting late.

He approached the beam, and found that he could not reach it.

It had been easy to steady himself as he dropped two or three inches, but to jump up and catch hold of the beam and draw himself up was another thing altogether.

He tried several times and failed.

There was but one way to descend; it was the one he had seen so often at the circus.

Beatrice must loosen the rope, and he must catch it as it swung toward him.

"Beatrice!" he called.

"Jack, are you coming down?"

There was magic in the question. It calmed his nerves, and he was able to make her hear.

He saw the rope slacken, and a new terror seized him.

Would the hammer strike the bell?

If so, would not the vibration throw him off the bell to the pavement beneath?

He grasped the chain which held the bell and waited a moment, and a noise which appeared louder than the loudest peal of thunder deafened him.

Every nerve tingled, his teeth chattered, his knees knocked together!

The aftermath of the sound, the echoing, the rumbling, the resonance, was fearful, and he almost wished for deafness.

He saw the rope swaying nearer and nearer to him every second.

With sudden impulse he reached forward and grasped it tightly in his hands. As he swung free from the bell, the hammer again descended, and the belfry was filled with the horrible noise.

The sudden clang of the great bell startled all those who were in the church and hundreds outside.

What did it mean?

The sound struck terror into the hearts of the superstitious.

It was the hour when a congregation had gathered for vespers.

The service had just commenced, the solemn words rang out from the officiating priest, when the first loud clang startled everyone.

The vergers hurried to the belfry; the door was locked.

No one was allowed in during service, and it was not known that anyone had outstayed the usual hour.

Walter Endicott and Amy Cottrell had looked in vain for the younger couple, and had imagined they must have returned to the hotel.

They heard the clang of the bell, but did not wonder what it meant; strange sounds and strange customs are always encountered in foreign cities.

A verger obtained the key of the belfry and entered.

As he reached the last of the stone steps he stumbled over something, which made him repeat a prayer and cross himself.

On the floor, grasping the rope in his hand, lay Jack Endicott, and over him was Beatrice Gregory, both overcome with excitement, and unconscious.

It was his duty, so he argued, to call in the aid of the civil authorities, and have the very wicked people who dared to faint in church sent to jail.

He hurried down the steps and out of the tower, across the great square to the office of the prefect of police.

He there told of certain unlawful acts committed by the two foreigners, and in most impressive language told how even the great bell had signified its displeasure by repeated clangings.

The prefect, knowing how foreigners were curiosity worshipers, humored the verger by sending an ambulance for the couple, but inwardly believed, that they had been overcome by fatigue and had fainted.

The two young people were carried down the stairs, still unconscious, and lifted into the ambulance.

The fresh air revived them a little, and they wondered whether they were awake or dreaming.

"Where are we, Jack?"

"I don't know, save that this wagon is worse than an old ox-wagon at home."

"It is shaking me awfully."

"I am sore all over."

Jack called to the driver, but no notice was taken.

The ambulance had not far to go, which was fortunate.

It stopped before the gates of one of those institutions to be found all through Southern Europe, where monks and nuns care for the friendless, the sick, and the unfortunate.

The prefect was there first; and as Jack and Beatrice entered he tried to look stern, but couldn't.

"Tell me all about it, young man," he said, in fairly good English, for which Jack was grateful, as his Italian was of a very amateurish nature.

Jack told his story, and related how he had climbed up to the bell and descended again, and how, when he reached the landing, he had been so exhausted that he fell down.

"That is all I know," Jack concluded.

"I thought he was dead," added Beatrice, "and felt so bad that I cried, and I suppose my nerves were overstrung, for I must have fainted."

"Ah! Now that I have heard your stories, tell me your names and places of residence. I knew you were English"

"We are not --- we are American. My name is Endicott! Jack Endicott; and this lady is Miss Gregory."

"Did you say Endicott?"

"Yes."

"Any relation to Walter Endicott, the explorer and correspondent?"

"His brother."

"Then we dine together this evening. Only just now the mayor has gone personally to invite Walter Endicott to dine with him, and I also am invited. I will order a carriage for you. I hope that no harm has been done either of you. But you really climbed up to that bell?"

"I did."

"And read the inscription?"

"There is no inscription."

"That is proof that you have been there, for certain private records declare that it is the only bell which is without any inscription --- "

"Then why does the guide-book --- "

"Guide-books are made to excite the curiosity."

"If I had been killed --- "

"Your curiosity would have been the cause."

Through the common sense of the chief of police, Jack and Beatrice escaped the penalty of their folly, and the story of the daring act of the young American was on every tongue.

The devout thought the boy had done wrong and committed a grievous sin, but the majority wished they had seen his act of daring, for mankind loves to witness feats of danger, and the greater the chance of disaster the more popular the performers are.

During the stay in Genoa Jack was even more of a social lion than his brother.

The Endicotts had a week to spend in Naples before the P. and O. steamer sailed for Penang and Singapore. Chapter III

The Americans mapped out how they would spend each day, following the advice of Walter, who twice before had spent a few days in the city.

The first day was spent in seeing the wonders of the city.

They walked through the Strada del Molo, or Street of the Mole, a street frequented by the sailors who, with their quaint headgear and bronzed features, were remarkably picturesque.

They listened to the open-air performances of Polichinello, the origin of Punch and Judy, and heard some professional storytellers tell their tales to the lazy Neapolitans.

Early in the morning of the day following, Walter marshaled his forces to visit Vesuvius.

In carriages the party proceeded to the ancient city of Pompeii, which was destroyed eighteen hundred years ago by an eruption of the mountain.

Leaving the city for a future opportunity, the party scaled the mountainside.

From its summit a small cloud of smoke arose, just sufficient to tell venturesome travelers that the volcano exists.

The sides of the mountain are covered with lava, taking the most beautiful tints and shapes, while other pieces looked like leviathan clinkers taken out of a furnace.

Beatrice and Jack were the first, as we may be sure.

The summit was reached, and the two looked down into the basin of the crater and admired the beautiful shapes assumed by the lava as it cooled.

The crater is nearly three miles in circumference, and at places two thousand feet deep, but the smoke and lava seemed to come from fissures of small size in the very centre.

Jack and Beatrice sat down on the edge of the crater and admired the weird effects produced by the rays of the sun.

As the rays shone on the lava it really appeared as though all was in motion, and that, instead of solid mineral, the lava was really a moving sea, with many-colored waves and strangely shaped rocks.

Beatrice waved to her friends to hurry, and incautiously stepped backward.

She lost her footing and fell down to the lava beneath.

Jack leaped after her, and found the lava so slippery that it was impossible to stand.

He caught Beatrice round the waist and tried to stay her downward descent, but he made her danger the greater, for his own descent added to the momentum, and they fell from rock to rock, fortunately without receiving any injuries save a few bruises.

A deep fissure was before them, and from it came a sulfurous smoke.

Jack braced himself against a great block of lava and succeeded in stopping their farther descent.

To climb up again was next to impossible, and Jack began looking for some way of escape.

He heard voices apparently close to him, and, thinking it was Walter and his friends, he called to them.

A strange voice answered in Italian:

"Keep to the right and you .can escape!"

The couple walked, or scrambled, along for some distance, when they found a smooth-cut passage, and standing in it a man, who was one of the handsomest Beatrice said, she had ever seen.

"This way if you want to get out of the crater," he said, and with the utmost faith they followed him some distance in silence.

Some strange feeling crept over Jack, and he looked.

The passage was dark and only light could be seen ahead.

While wondering where the passage would lead to, both were seized in the strong arms of some men, and the one who had guided them laughed loudly as he exclaimed:

"You are our prisoners, signor and signorina."

The Italian was an outlaw, Galbardo by name, who had a secret hiding place in the subterranean passages of Vesuvius. He held the two prisoners for several hours, then took everything of value they had about them, bandaged their eyes, and had some of his men conduct them to a boat, in which they were set adrift after nightfall on the bay of Naples.

But Jack used the oars to good advantage, and in due time the two reached land, thankful that their misfortunes had been no worse.

There was considerable rejoicing when a cabriolet stopped at the door of the Hotel Albion and Jack handed Beatrice out of the vehicle.

They had been given up as lost.

All believed they had fallen into one of the fissures in the volcano crater, and were beyond human aid.

Walter attended to his brother and obtained an account of his adventure.

It was so startling that the newspaper man at once saw that he could turn it to good account, and a sensational, yet true story was sent off to the home paper.

The authorities were interested and professed to desire knowledge about the entrance and exit to Galbardo's hiding-place, but though Jack gave all the information he could, no move was made to profit by it.

The young explorers had two days more to stay in Naples before the P. and O. boat would leave for Penang.

During those days they were lionized and fˆted.

Walter Endicott sank into insignificance beside his brother, who was the social lion, and spoken of as the one who had escaped Galbardo's vengeance.

A very pious, wealthy, and superstitious old lady showed her appreciation of Jack Endicott by presenting to him a little box which was said to contain a relic of great antiquity.

She had refused large sums of money for it, declaring that it should never go out of her possession.

The relic was said to preserve its owner from all danger in travel by sea and land. The owner had given up all thought of travel, and, being excited by the stories told about the New Englander, in a fit of enthusiasm presented the relic to Jack.

He laughed at the solemnity with which she had handed over the precious box, but as he began to hear stories of its wonderful virtues he commenced to prize it more highly.

The newspapers mentioned the generous gift, and before the day was over Jack received offers for it.

Clergymen wanted it for their churches and captains for their ships.

Had Jack auctioned it off he would have been the recipient of a large sum of money.

But, apart from its alleged wonderful properties, he would not part with it on account of its being a gift.

"Jack, my boy, breakfast at eight sharp; I want to be on board soon after nine, and then we'll bid farewell to civilization for a time," Walter had said as he left Jack's room early in the evening of their last day at Naples.

There was a reception given in the parlors to the two brothers by the guests, and Walter knew there would be but little time for private conversation before bedtime.

Beatrice Gregory was nearly heart-broken.

She had become so chummy with Jack that she had lost her heart, and was very positive life would be a dreary waste without him.

As for Jack, he liked Beatrice, and wished she was of the masculine gender, so that she could go with them.

Beatrice found an opportunity to get Jack alone in one of the alcoves of the great parlor, and, sheltered by the friendly leaves of tropical plants, she asked him how soon he would forget her.

"I shall never forget you, Beatrice."

"Never?"

"Never. You will always be in my mind."

"Jack, will you give me something as a memento of the happy days we have spent together?"

"I --- don't know what I have --- "

"That little ring."

"Which ring?"

. "That silver chain ring."

"Why, that is not worth anything."

"It would be to me. I should prize it more than the most costly thing you could purchase."

He had it in his vest pocket. It was only a simple ring, worth perhaps a dollar, but he had worn it, and, therefore, she valued it.

He gave it to her, but she passed it back.

"Place it on my finger, Jack."

He did so, and the strains of a waltz coming across the room to their retreat at the time, he drew her arm over his and led her to the ballroom.

She would rather have talked, but then, she was a girl and was in love, while Jack was a boy and thinking of the life of adventure in which he was to engage.

As the young couple whirled round the room a pair of black eyes watched them. The man stealthily moved nearer to them, hiding behind the palms and other plants, so that he could see and remain unseen.

"He has the mascot," muttered the man. "I would give all I possess to obtain it. I will have it, even if I have to --- Bah! why should I kill him? I can get it without."

All unconscious of the proximity of a thief, Jack talked with Beatrice about the mascot.

"I would like to have it just for one night," she said.

"You shall have it if I can get it before breakfast in the morning."

"May I? You are good."

"Yes; I will give it to you before the evening is over."

"I shall feel that it will bring me good luck."

"What good luck do you want?"

"The knowledge that we shall meet again."

"And you think the relic will bring that about?"

"I shall feel that, as long as you possess it, I have an interest in you because I shall have held it for one night."

"So the girl is to have it to-night! So much the better!"

Neither Jack nor Beatrice were aware of the man's presence, and, therefore, knew nothing of the danger which threatened.

Jack slipped away from the parlor during the evening, and returned carrying the precious relic.

There was just a suspicion of astonishment when Beatrice saw the box, which was no larger than a snuff-box, and looked very like one.

It was made of some hard wood, richly inlaid with gold and ivory.

"What is the relic like?"

"I don't know; the box cannot be opened without breaking."

"Then how do you know there is anything there?"

"I do not know. Faith, you know, works wonders."

The hour for retiring had arrived.

"I shall not wish you good-by, Jack, for I shall see you in the morning, and again when that wretched steamer sails."

"Till the morning, au revoir!"

"Au revoir!"

Beatrice retired, carrying with her the precious relic.

Amy Cottrell was all curiosity to see the box, and would have forced it open had it belonged to her.

They occupied adjoining rooms, and spent always an hour together before retiring for he night.

But that evening Beatrice was not inclined to talk, and she almost bruskly wished her companion and friend good night.

Beatrice placed the relic under her pillow and tried to sleep.

But her brain was too active; her thoughts coursed so quickly through her mind that it was impossible to sleep.

Jack and Walter occupied two rooms almost directly opposite Amy and Beatrice, and they, too, did not feel inclined for much talk; they knew they had an exciting day before them on the morrow.

But however restless people may be, sleep comes at times, though it may be at fitful intervals.

Amy was fast asleep, and the secret may be told --- snoring in tune and out of tune.

Beatrice at last was overcome, and she, too, sank into a fitful sleep.

Beatrice dreamed of the relic beneath her pillow, and thought of its value.

She feared it might be stolen, though she could not imagine who would know she had it.

In her dream she fancied some one opened her window.

The dream was so real that she awoke.

She burned a night-light, and even in its dimness she saw that the window was closed.

"It was only a dream," she murmured, as she felt beneath the pillow and found the box was safe.

She seemed fascinated by the window, and could not keep her eyes away from it.

As she gazed she saw the Venetian blinds sway; then they were drawn up.

She looked, spellbound, and dared scarcely breathe.

No one was in the room, and yet the blinds were drawn up.

She lay perfectly still and motionless, watching with breathless interest.

The window was gradually raised, and a man stepped into the room.

Her tongue was loosened.

She screamed as only a woman can scream.

Amy awoke and rushed into the room; and got between the burglar and the window.

Jack heard the scream, and, pushing open his door, rushed into the corridor, and, without staying to consider the proprieties, smashed in the door of Beatrice's room and, seeing a man with his hands on the girl's throat, he flung himself on him and bore him to the floor, just as the hotel porter reached the room.

"What means this outrageous scene?" demanded the hotel proprietor, as he looked through the smashed door.

The hotel landlord looked the very personification of offended dignity. Chapter IV

He saw the smashed door, and pretended to be very indignant; but it was only pretense, for he had not been a landlord in Naples all these years without knowing that his guests would pay three times the value of the smashed door.

To see a struggling mass of humanity on the floor was enough to disconcert anyone.

The landlord looked as though he would leave the parties to fight it out among themselves, though there was enough chivalry in his heart to cause him to think that two ladies would not be the aggressors in a fight at night, especially when clothed only in their robes de nuit, and therefore they must have his sympathy.

"Ladies, what is, the matter?" he asked; but no one took any heed.

When Jack knocked the burglar down, Beatrice was freed; but the shock had been too much for her nerves, and she had fallen to the floor unconscious. I

The burglar, with Jack on top of him, struggled to escape, and in doing so held the fallen Beatrice in a position which made it impossible for her to rise, had she been sufficiently conscious.

The porter had his hands round Jack, thinking the young American must be the aggressor, and Amy was equally sure that the porter had no business to hold Jack as he was doing, so she had joined in, and was almost squeezing the life out of the hotel servant by the grip she had on his neck.

"Ladies, ladies!" exclaimed the landlord; and then, seeing that no notice was taken he shouted:

"Desist, or I will send for the police!"

Still the struggling continued, and might have ended disastrously, had not Walter Endicott been roused from his slumber and gone to the scene of action.

He knew something unusual had happened, so he took his revolver, and, as he pushed past the landlord, he shouted:

"Stand up; all of you, or I shall fire!"

Amy screamed and released the porter.

Her hair was hanging over her face and shoulders, having escaped from the pins which had held it in order.

"Oh, Mr. Endicott, they have killed Beatrice, and are killing your brother!"

Walter saw that one of the hotel servants was on the top of his brother and would not relinquish his grip.

Placing his pistol at the porter's head, he threatened to shoot him unless he got up.

The threat had the desired effect, and the porter and Jack separated; then Walter saw the burglar for the first time.

The man, as soon as he was released, made for the window.

"Stop, or I'll shoot!"

The man took no notice, but put one leg over the window-sill, and was dragging the other over when there was a loud report, and the man felt a sharp sting in his hip.

"Don't shoot! I'll come in," the man whined in Italian, or, rather, in the patois of the Neapolitan lazzaroni.

Walter did not lower the pistol until the man was standing in the room; then he made the fellow hold up his hands.

Covering him with his pistol, he asked Jack what it all meant.

Beatrice prevented Jack replying.

"I will tell you. I borrowed from your brother the relic or mascot. By some means this man found out that I had it. I had just fallen asleep when I felt him in the room. I screamed. Your brother heard me. He burst in the door just as this man was strangling me. See, here are the marks on my throat. Your brother saved my life. He is a true hero."

"But, what was the porter doing?"

"I --- I beg the signor's pardon, but I thought he was the offender, that he had burst into the lady's room and was killing her. I do most humbly ask the gentleman's pardon."

"And when I saw his mistake," said Amy, "I tried to get him away, and we all rolled about on the floor, and --- it was very funny."

Amy saw the humorous side of everything, and as she laughed, so did the others, until Walter suggested that the landlord should find other rooms for the ladies, and, as they were not in a presentable state, that they should retire.

The burglar was secured and handed over to the authorities.

He was at once recognized as one of Galbardo's band, and acknowledged that he had been at the party with the sole object of securing the mascot.

If he possessed that treasure, he thought, no harm could ever come to him.

So much did the authorities dread the power of the brigand and his band that scarcely had the P. and O. steamer left Naples, carrying the Endicotts to the unknown worlds they were to explore, than he was released, the authorities declaring that there was not sufficient evidence against him.

Beatrice and Amy retired, but it is doubtful whether they slept that night.

At breakfast Beatrice looked as though she had been weeping, and Amy was in about the same condition.

The farewells were uttered on the dock.

Amy asked Walter to remember her, and Beatrice hoped Jack would not forget her.

Jack clasped her hand in his and vowed eternal friendship, while Waiter hoped he should meet Amy again before many years had flown by, and that she would still be the happy woman he had known on board the Atlantic liner and in Genoa and Naples.

The mails were aboard, and the great ocean palace steamed out of the dock.

On the land the people waved their handkerchiefs and the men raised their hats, the salutes being responded to by the Endicotts, who were the only passengers from Naples.

Jack was delighted with the steamer, and he soon became a favorite. Chapter V

"Hello, there, Endicott! Where are you bound to now?"

The speaker, a grizzled veteran, had been suffering from malarial fever, and had not seen Walter until that morning.

"Forbes, old fellow, whither bound?"

"I asked first."

"So you did. Wen, I am bound for Cochin China."

"And I to Singapore, taking the trip just for health. I shall go overland and return by way of Bombay."

"Pleasure?"

"And business. A newspaper man cannot afford to take a thousand-pound trip for pleasure."

The speaker was Archibald Forbes, the world- famous war-correspondent.

"Do you know anything about Cochin China?"

"Not much; but I would like to be able to explore the forests of the North. I believe --- don't laugh at me, for it is only an idea, a fancy --- but I have the belief, all the same, that in the forests of Anam an ideal race of men exists. There is an old superstition that the Garden of Eden is still in existence, and many believe it is situated in the depths of those forests."

"If it is, we shall find it. Forbes, behold my brother Jack, the most youthful accredited explorer ever known."

"By whom accredited?"

"The French Geographical Society."

"My boy, you are commencing early. Let me give you a bit of advice --- stop early. Do not let all your manhood be spent away from civilization."

Days passed, the good ship sped on through the waters of the Mediterranean. Port Said was reached, and a stoppage of a few hours allowed the passengers to stretch their legs by a walk through the town, and enabled them to say that they had been in Egypt.

The Suez Canal, that triumph of engineering skill, excited the sentimental admiration of all, though it is but a deep and wide and muddy canal or, as the satirists called it, ditch.

Past Ismailia, with a view of the minarets of Rameses in the distance, the wretched land of the Pharaohs was traversed.

Suez was reached, but the steamer did not stay long enough for the passengers to land.

On through the Gulf of Suez, with Sinai on the left and the Egypt of the barbarous tribes on the right, the Red Sea was entered, and Jeddah, the port where Mahomedans disembark on their pilgrimage to Mecca, was saluted as the steamer passed.

At Aden a stop was made for the Indian passengers to be transferred to another steamer bound direct for Bombay.

The long journey was continued through the Arabian Sea, past the Maldine archipelago, skirting the Island of Ceylon, and reaching Penang, on the Straits of Malacca.

Here Walter and Jack left the steamer amid the tearful farewells of the passengers, who had become attached to them on the voyage.

Penang or Pulo Penang, signifying Betel Nut Island, called also Prince of Wales Island, is a very important part of the Straits Settlements, and valued by England because of its strategic position.

American and English manufacturers send their goods to Penang, to be from there distributed among the suitable markets of the Orient.

Jack soon realized that he was in, to him, a new world.

Out of the 135,000 people who inhabit Penang and Wellesley, only about 600 are of European descent, the remainder being Chinese, Malays, Burmese, Bengalese, and Siamese.

The road up from the dock was shaded by rows of cocoa-nut and areca-plants, some of them, rising to a height of two hundred feet, with trunks so slender that it seems almost impossible to conceive that they should support the weight of branches and leaves at the top.

Walter knew his way about, and was welcomed by the customs officers, who had seen him before.

One of the officials, who had become thoroughly nationalized, took out his betel-box and offered it to Walter.

The American took a small portion, but carefully refrained from putting it in his mouth.

Jack saw everybody chewing, and was alarmed to see them expectorating a blood-red saliva.

It was the betel-juice.

The betel consists of a leaf of strong pepper, plucked green, spread over with moistened quick-lime, and wrapped around a few scrapings of the areca-nut.

A strong narcotic is thus produced, which, in persons unaccustomed to its use, produces giddiness and deadens, for a time, the sense of taste.

It burns the tongue and throat, and is extremely unpleasant to those who chew it for the first time.

It gives a deep red color to the saliva, so that the lips and teeth appear covered with blood. Its habitual use destroys the teeth, and Jack noticed that even young men were toothless.

"Never touch it, Jack, for if you do you will continue to use it, and the habit is hard to break," said Walter.

"But you say it is very nasty."

"Extremely so, but seeing everybody uses it, you try again and again, until its taste is pleasant."

Walter wanted to go to Georgetown, and selected some strong carriers for a palanquin.

It was a new kind of travel for Jack, and he really pitied the men who bore the burden of the palanquin and its two occupants, but they had made it their business and it was the surest mode of travel.

The road was hilly and rocky, and in some places so bad that no horse or mule could possibly traverse it.

The palanquin selected by Walter, he told Jack was more luxurious than those ordinarily used.

As my readers may never have seen a palanquin, it may be well to describe it.

Imagine a box about eight feet long, four feet wide, and four feet high, with wooden shutters which can be opened and shut at pleasure, for the purpose of admitting air or excluding the scorching rays of the sun. The interior is furnished with a cocoa mattress, well stuffed and covered with leather, on which the traveler reclines; two small cushions are placed under his head, and one under his thighs, to render his position as comfortable as possible. At one end is a shelf and drawer, and at the sides are nettings for containing articles necessary during the journey.

At each end of the palanquin, on the outside, two iron rings are fixed, and the bearers, or hamals, of whom there are four, two at each end, support the palanquin by a pole passing through these rings.

The palanquin was very comfortable, though the rate of speed was most disagreeably slow for those who had been accustomed to the railroads of civilization.

Over the roads of Penang, across the hills to Georgetown the bearers did not go more than one and a half miles in the hour.

While fortunate in the choice of the palanquin, Walter had been very unfortunate in the selection or bearers.

They were Malays, and Walter did not know that there were disputes going on between the Malays of the coast and those of the hills.

These disputes always led to fighting, and the unfortunate traveler often got the worst of the encounter.

It was getting late, and not more than half the distance had been covered, when Walter heard a shouting and screaming which foreboded mischief.

The palanquin was dropped.

Not placed on the ground, but thrown down with such force that every bone in the travelers' bodies seemed to be bruised.

Walter struggled to his feet, striking his head against the top and trapping his fingers in the shutters.

He opened the door and crawled out, bidding Jack follow him.

They were on the mountainside, on a road which was merely a narrow ledge projecting from the mountain, and not more than five feet wide.

Above them the rocks seemed to rise almost perpendicularly, while on the other side a steep declivity threatened their lives.

The bearers had disappeared down the declivity, while a score of murderous Malays were seen approaching the palanquin.

They were armed to the teeth, literally as well as figuratively, for each man carried a heavy and formidable dagger between his teeth.

"It is war to the death now, Jack!" Walter said quickly. "Let me see of what you are made."

Walter knew that the Malays were a treacherous people, and that they were as cruel as any human being could be. Chapter VI

He had often thought he would rather die than become a prisoner or the Malays, and he told Jack that he must not be taken alive.

The Malays looked at the retreating palanquin bearers and seemed to hesitate whether to follow them or to attack and plunder the Americans.

Walter made ready to receive the Malays, and even engage them as bearers to Georgetown, if they would accept the overtures of peace.

Of this he had but little hope, for they were too fond of plunder to agree to work for money.

They approached nearer, and one big, powerful fellow, who was evidently acting as chief, addressed the Americans.

He spoke in the Malay tongue, which Walter understood fairly well, but he chose to make them speak English.

"What is it you want?" he asked.

"By the beard of the Prophet! the white dogs must give the children of the Prophet all they have."

The English was good, though the accent made it sound barbarous.

"The sons of the Prophet have made a mistake; the white men are not dogs, but Americans."

"Americans have lots of money, and the dogs must give it to the sons of the Prophet."

"We will pay you to dawk us to Georgetown."

"We are not hamals."

"Then what do you want?"

"We have told you."

"Then let us pass, for we shall not give money to you."

A howl of indignation went up from the Malays, and instantly they rushed along the narrow road toward the Americans.

"Fire, Jack, but do not miss any. Let me fire first; you follow quickly."

Walter waited until the chief was almost close to him before he fired.

The shot took effect, and the Malay rolled down the rocks.

Jack fired at the second man, and though he not did kill him, he wounded him so badly that he staggered over the rocky precipice.

The others saw the determined stand made by the two Americans, and hesitated whether they should face death or accept the terms offered by Walter.

After a brief consultation, they held up their hands, with the palms out, in token of surrender.

"By the beard of the Prophet, thy servants will carry white men to Georgetown."

Walter held up, his hand, palm outward, as a sign of peace.

Then he spoke with Jack in a low voice, all the time having his revolver at full cock, in case of emergency.

"If we use these fellows, we must have our wits about us, for they are treacherous."

"All right, Walter; anything better than fighting. I feel awful bad to think I killed a man."

"Call that fellow a man! Why, Jack, if a Malay is a man, an American must be an angel."

Walter made arrangements with the Malays to take the palanquin to Georgetown. "Mind you, if I find any treachery I will shoot you like the dogs you are!"

The men grinned as they heard the threats and placed their daggers in the sashes they wore round their waists.

The Americans got inside the palanquin, and the Malays took up the poles and carried it along at a greater pace than the first men had done.

Jack was delighted, for he thought his brother had misjudged the men, and that they were better than he was led to believe.

Walter was thoughtful, and doubted the honesty of the carriers.

A peculiar noise, similar to the opening of the call to prayer by the muezzins, caused Walter to startup and look through the window.

Almost at the same moment the palanquin was dropped to the ground.

Walter opened the door, and saw at once that they were caught in a trap.

Instead of being on the mountain road, they had been taken to a blind alley, so to speak.

The rocks rose up very high, and almost perpendicular in front and on one side, while on the other side was a precipice so steep that it made Walter almost dizzy as he looked down.

There was but one way of escape, and that was the way they came, but the Malays guarded that and mocked the Americans.

"Your money, you dogs!" the Malay in front demanded.

Walter raised his pistol.

"Begone, or I'll kill everyone of you!"

The men laughed and asked how he could do so.

Perhaps they did not know the capabilities of a good revolver, for they certainly did not flinch, but laughed loudly as Walter held the weapon at arm's length.

"I give you two minutes to march"

Another laugh was the response.

Walter Endicott disliked taking human life, but what was he to do?"

Was he not justified in saving his property, and perhaps his own life?

He thought so as he pulled his revolver.

The bullet went through the shoulder of the foremost Malay who changed his laughter to a look of the most intense surprise.

The man raised his hand to his shoulder to staunch the blood, and whispered something to his followers.

They evidently agreed, for all turned round and ran as fast as their legs could move.

"We must walk, Jack."

"All right, Walter. How far have we to go?"

"I do not know, but I suppose five miles."

"That is nothing. Which way do we go?"

"There is but one way out of this place; and after that I do not know which way."

"Let us start, or we shall be lost in the darkness."

The baggage was heavy, though the major part had been left at the port, and the travelers only carried what they absolutely needed in a semi-hostile country.

They kept their revolvers in their hands, ready for any emergency, and retraced their steps until they regained the main road.

Walking side by side, they laughed and chatted over their adventures, and wondered how many more they would meet with before they left civilization behind them.

Finally they reached Fort Cornwallis. The governor, Sir George Gray, extended his hand with generous warmth, as the Endicotts entered his mansion.

Gray talked, Walter and Jack listened, until Lady Gray entered and then more warm words were spoken, and the travelers were made to feel that it was worth crossing hills to receive such a welcome.

"I am always so glad to see Americans," said the lady warmly, "and I have always thought that if I were not Irish I would like to be American."

But you see she is Irish, and she is so fond of that 'tight little island' that she had a shipload of Irish soil brought here.

"So you intend to explore the Lao and Moi countries?" said the governor, after a time.

"Yes, I know that I shall find many things there worth knowing."

"But Endicott, is it worth while?"

"Of course, governor, all knowledge is worth having."

"In the abstract, yes; but just consider. Remember how many lives have been lost in searching for the northwestern passage, or, in other words, the North Pole. Now, how much better would the world be if the English, or the American flag was stuck on the northern axle of this world of ours? Believe me, Endicott, a human life is of more value than the discovery of the North Pole."

"I differ with you, governor, and if I live through the next few years I hope to go to the North or South Pole."

"You are an enthusiast, Walter Endicott."

"So was Columbus and Ponce de Leon; and so was Torres, who discovered Australia, and Tasman, and the host of others who have made the world rich by their explorations."

"But you do not expect to find a new world at the North or within the antarctic circle?" asked the governor's wife.

"I hardly hope to do so, but, believe me, the world will be better for all knowledge."

"What say you, Mr. Jack?" asked the governor.

"I would rather discover a little island than be King of England."

"Then, as you are both agreed, all we have to do is to lay out the plan of campaign. You Americans are a very independent people, but you find John Bull very useful at times."

"My dear governor, no nation is really independent. We have to assist and depend on each other, just as individuals do."

"I will give you a letter addressed to all English consuls, military officers, and missionaries, and then I shall have done all I can."

"You are kind, and the letter will be of use to us through the Malay Peninsula."

"I think I shall cross with you to Quedah; I don't like parting with you soon."

The governor of the Straits Settlements had considerable influence throughout the Malay Peninsula and in Siam, therefore a letter from him was the most useful introduction.

At Quedah, with its strange buildings, and still stranger people, the governor parted with the Americans but not until he had given them advice concerning the men to be employed.

"Get Mussulmans if you can, for they will be faithful. Never trust a Malay.

The governor returned to Penang by way of the province of Wellesley, while Walter and Jack proceeded to the residence of the Rajah of Quedah, to pay their respects.

The kingdom of Quedah was supposed to be under the suzerainship of Siam, and paid a yearly sum to the king of that country, but England really did as she pleased with the rajah and his country.

Like all princes and rulers under the protection of Great Britain, the rajah considers every new arrival of white men as a menace to his power.

He lived in constant dread of England, and, therefore, felt greatly relieved when Walter sent a messenger carrying the American flag forward to crave an audience.

The rajah came forward to bid the Americans welcome and in his broken English told them that:

"Melicans no stealee country; only Inglese do that."

To show his welcome he ordered his grand vizier to prepare an entertainment worthy of his guests.

They were entertained by the rajah at dinner and spent the night in the palace.

Walter chafed at the delay, but submitted with good grace. Chapter VII

With a number of Mohammedans specially engaged through the aid of the British consul at Quedah, the Americans started on their journey through the Malay Peninsula.

After leaving Quedah, Walter negotiated for a number of buffaloes for riding, and carrying the baggage.

Jack was surprised to find these noble animals could be tamed sufficiently to be used in harness.

The Mussulman guide, who rejoiced in the name of Mahomet Ali, warned Walter of the dangers to be encountered.

"Near the sea," he said, "we have the orang-laut" --- literally 'men of the sea,' or 'sea-robbers' --- "and if we go too near the mountain forests we are in danger of meeting with the orang-banua" --- or wild men.

"We leave the route to you, Mahomet Ali, and your head will fall in the dust if you guide us to our enemies," answered Walter.

"Thy servant is not a dog that he should betray thee," Mahomet Ali replied, with dignity.

The guide was cautious, and sent two men at least a hundred yards ahead to clear the way.

Jack was riding his buffalo and getting used to the strange sensation, when he suddenly exclaimed:

"What's that?"

He threw himself forward until his whole length was on the back of the buffalo.

He had been startled by one of the huge bats peculiar to that region.

The vampire, or kalung, which hovered over Jack's head was as large as a crow, with wings at least two feet across, having sharp, clawlike projections along each wing.

The head of the vampire was like the shriveled head of an old man, in miniature, and was horrible to look at.

Walter raised his rifle and shot the bird-beast.

The Mussulmans fell to the ground and buried their faces in the sand, as they repeated prayers to Allah, for they thought it very unlucky to kill a kalung.

The journey continued without further interruption until the men who were riding forward were seen to throw up their hands.

Those behind got ready for a fight, but the enemy was one they could not conquer.

The leaders had suddenly struck one of those quagmires, or quicksands, which make the traveling so dangerous.

In a few minutes the buffalos and their riders had sunk into the quagmire, and were lost to sight.

Hundreds of natives perish in the same way every year.

Mahomet Ali congratulated himself on his foresight in sending others ahead, thereby saving himself.

A new danger confronted them.

The breaking of young trees and the shaking of the ground told Walter that a herd of Indian elephants, the most ferocious of their kind, was on the rampage.

They had scented danger, and, instead of flying from it, had gone to meet it.

Walter drew close to Jack and gave him directions how to act.

"It is no child's play, Jack, but there is no escape."

"I do not want to escape, Walter. I want a good chance at the noble game."

"You will have it. Keep a firm seat, and don't fire rashly. Better not fire at all than to enrage the beasts."

Walter stationed his men on three sides of the quagmire, hoping that the elephants would charge straight ahead and be swallowed up.

But the Asiatic elephants have reasoning powers to a great extent, and it seemed they talked the matter over, for the herd suddenly stopped, while an old bull marched forward with stately step.

"Don't fire, but watch!" shouted Walter, as Mahomet was about to fire at the approaching elephant.

The bull snorted and raised his trunk in the air. He scented danger.

After looking at his enemies he rushed forward, and was caught in the quagmire.

His weight caused him to sink very rapidly, but as he sank he gave a series of bellowings, which were answered by the herd.

It was the call of the dying to his friends to avenge his death.

The herd divided, and rushed forward to attack the men on right and left.

Jack was just behind Walter, when a huge bull elephant bore down upon the buffalo Walter was riding, and struck him with such force that the buffalo and its rider were thrown to the ground.

Jack leaned over the head of his buffalo and fired at the elephant.

It was his first shot with so heavy a rifle, and the concussion nearly threw him to the ground.

Walter had risen to his feet, and, standing almost under the elephant's head, fired.

Jack's shot had wounded the bull; Walter's killed it.

As it fell three others came to avenge it.

Walter and Jack were on the ground, and used the dead elephant as a barricade.

It was a critical position, and their chances of life were but small.

Mahomet startled them by the cry:

"My lord and master, there are five elephants in the rear!"

"Then we are lost!" answered Walter. "Good-by, Jack, in case we should fall!"

The Asiatic elephant is a far better fighter than its African brother, but, like it, the elephant never cares about being the aggressor. Chapter VIII

The killing of the big bull was an act which must be avenged, and the elephants certainly had the best position at the time Walter bade his brother good-by.

The five elephants came marching up with stately tread, and as regularly as soldiers on the march.

When they were within a few feet of the Americans, five trunks were raised and trumpetlike notes given.

Mahomet had his men closing in on each side, and as the five elephants pealed forth their defiance, he signaled his men on the right to fire a volley at the massive brutes.

Two shots took effect, but neither fatally.

One of the bulls walked over to the attacking party as deliberately as though he were on friendly mission bent.

Mahomet called to his man to be on his guard.

But the warning was too late.

The elephant had got close to the man before he was aware of its proximity.

Winding his trunk round the body of the Malay, he carried him some little distance, and then hurled him with terrific force in the direction of the Americans.

The poor fellow was killed, but his murderer did not live many minutes, for a shot from Jack's rifle struck a vital part and he fell dead.

One of the attacking elephants, a female, uttered a peculiar cry, which was answered on all sides.

An elephant, the largest bull Walter had ever seen, was approaching.

No sooner had he shown himself than the Americans and Malays were forgotten.

All the elephants started in pursuit of the newcomer, and the Endicotts were left in possession of two dead elephants, which were only valuable because of the amount of ivory in their tusks.

"What made them run away like that?" Jack asked.

"Evidently the newcomer had been expelled from some herd for misconduct."

"Ha, ha, ha!"

"You laugh, Jack, but it is a fact that each herd has its government, and a means of communicating with other herds. If an elephant is expelled for bad conduct, he has to wander about alone, and every herd in the district will chase him away."

"That seems like intelligence."

"Yes, and I will tell you another thing. If the leader of a herd is attacked, the others will force their way to the front; and will place him in the center, giving their lives to save his."

"If the sahib wants to live, he had better leave," exclaimed Mahomet Ali hurriedly.

"Why?"

"The elephants will mourn their dead, and the jackals will hear and come to the feast."

"And then?"

"The elephants will return, and we cannot fight them."

While the conversation had been going on the men had been busy removing the tusks from the dead elephants, a task requiring great skill and deftness.

The tusks were particularly fine, and worth considerable.

Walter gave one set to Jack and the other to Mahomet and his men.

This act of generosity pleased the men, who declared their fealty again and again by all the adjurations known to the followers of Mahomet.

It was not long before the tramp of the elephants could be heard, and Walter gave the sign to start.

The journey through the forests and jungles was one full of adventure and excitement.

Frequent attacks by jackals and hyenas, occasional encounters with lions, and two engagements with elephants gave Jack plenty to record in his diary.

"Walter, look at that cloud," said Jack, when they had camped one evening.

"That is no cloud; it is a flock of birds."

Mahomet was seen gathering his men with haste.

Walter watched and saw the men pulling up the grass and getting wood and brambles and dried leaves together.

"What is it, Mahomet?"

"Bats."

"Well?"

"Only fire will keep them away; do you not see that they fly from right to left?"

"I see that, but what does that signify?"

"Is it not written in Alkoran, the word of the most high prophet, that the flight of birds from the right to the left is a portent of disaster?"

Mahomet Ali knew the Koran well, and was really a very learned man as far as the religion of his great namesake was concerned.

The men lighted the fires quickly, but the bats were too near for the fire to be effective.

They flew within a few feet of the ground, turning over tents, upsetting the food of the buffalos, and carrying the men off their feet.

It was like a whirlwind of living animals.

The buffalos were frantic, tossing their heads about and bellowing loudly.

The vampires, for such they really were, cut the flesh of the animals with their wings as they flew past, while the loose clothes worn by the Malay guides were torn into ribbons.

Jack had his cheek badly cut and his clothes damaged.

Walter was the only one who escaped without injury.

"Allah il Allah!" exclaimed the devout Mahomet Ali, when he arose from the ground after the vampires had flown by.

The exclamation was the signal for all the Mohammedans prostrating themselves in the dust and beating their fore-heads on the ground.

This was repeated three times; with frequent ejaculations of the name of Allah, concluding with the exclamation in Arabic:

"Great is Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet!"

The journey was then continued, and no new adventure added zest to their tiresome march.

Siam was entered and a new phase of life seen.

The southern Siamese are an almost intellectual people, and the travelers met with a warmer and more hearty welcome than from the Malays.

Mahomet Ali would not go farther than the boundary-line, neither would he allow any of his men, so the Endicotts found themselves once more alone in a strange country.

They had purchased four buffalos, two for burden.

It was a scene which would have surprised a Western cowboy.

The Americans were each riding a fierce-looking buffalo and leading another. The animals were the finest of their kind, their great heads adding to their stupendous grandeur.

When the travelers arrived within sight of Bangkok, the capital of the Siamese kingdom, they were amazed and charmed by the profusion of gilded domes on temples and palaces.

"It is as new to me as to you, Jack."

"Have you never been to Bangkok?"

"No."

"Mahomet told us that we should have to leave our buffaloes at Tsiang. Why?"

"Bangkok is like Venice, the streets are waterways; only in the district of the palaces are there roads. In Bangkok the houses are either built on piles eight feet above the ground or else are really floating houses on rafts. The city is surrounded by a high wall. Bangkok has half a million population, but the wall is six miles long."

"How high?"

"Fifteen feet, and twelve feet wide; a good road, they tell me, runs along the top of the wall."

"Does the wall float?"

"I see you do not believe me."

"Oh, yes, I do, only it seems funny. But here are some houses; perhaps we have arrived at Tsiang."

"You guessed correctly. This is a Chinese village, and every man pays a dollar a year for permission to live here."

"Do you talk English?" Walter asked an almond-eyed, sleek and oily Celestial.

"Me talkee anything; me takee money!"

"I have no doubt about that. If you understand me --- "

"Me know Inglese belly well."

"Then we want to leave our buffaloes with you for a few days. We want to go to Bangkok. We want a boat. Understand, if you hurt the animals, or touch our baggage, I will shoot you."

"Me no flayde; Inglese no meanee what dey say."

"We are not English, we are American."

"Melican man Chinaman fliend. B'floes alive rightee."

After considerable fuss, the Chinaman got a boat ready, and so great was his appreciation of the honor that he paddled it himself.

When the party got within a stone's throw of the City wall a scream startled them.

The Chinaman began talking loudly, to try and drown the sound.

Walter bade him be silent.

"Melican man no likee talkee."

"Stop, I say!"

"Melican man getee angry."

Walter put his hand over the boatman's mouth, and Jack placed a pistol at his head.

"Speak another word, and I'll shoot!" said Jack spunkily. The man dropped his paddle and wondered what sort of people he had met.

Jack saw three men drag[g]ing a child along.

The child was screaming loudly and struggling to get free. With a bound Jack cleared the narrow streak of water between the boat and the bank of the canal, and was quickly followed by his brother.

"Save me; bad men steal me!" cried the child, in good English.

Walter looked at the child-thieves for only a moment, but long enough for him to determine that the child was right.

He let out with his left with a vigor which would have been a credit to John L. Sullivan in his palmiest days, and caught one of the men on the mouth.

The man fell like a log.

The other two pulled out long, sharp daggers, and set upon Walter and Jack with an alacrity worthy of a better cause.

Walter had no desire to use his pistol, because he might embroil himself with the authorities; he well knew that a native's word would be accepted in preference to that of a foreigner.

Jack did not care so much for the consequences --- he thought only of saving his life; and, whipping out his revolver, he bade the fellow put up his dagger.

The man laughed and raised the weapon threateningly.

Jack pulled the trigger of his hammerless pistol, and the bullet struck the man's right wrist, causing the dagger to fall from his hand.

Jack picked up the knife and turned it against its former owner.

The fellow threw himself on the ground and cried for mercy.

Seeing that the Americans had the best of it, the natives ran away as fast as their bow legs would let them.

"Where is the child?" asked Jack.

"I was going to ask you the same question."

"There was one, and he has not gone with the thieves."

"Of course, there was one; but where has he gone?"

"Was it a boy?"

"I think so."

"Perhaps it was a girl."

"Jack, you are a philosopher, for if it was not a boy it must have been a girl; but it --- I will still use the neuter --- has escaped us."

When the Endicotts got back to the canal they found the Chinaman fast asleep in the boat.

Rousing him, they bade him go to work and get them into Bangkok as soon as possible.

"Melicans save the childee?" asked the heathen Chinese, with a smile that was childlike and bland.

"Yes."

"'Where is he? Me no see him."

"Gone home."

"Melican spoilee fun; de men hab a hate 'gainst Melican."

"All right; we can stand it. Go ahead."

The boat shot along, and was soon through the gate and within the city.

Jack rubbed his eyes to find out whether he was awake or dreaming.

The houses were all perched upon piles, in some cases over the water and above multitudes of boats which shot hither and thither.

Then there were houses, as Walter had said, which were built on rafts and anchored on the broad sheets of water in the center of the city, which was really an estuary of the Gulf of Siam, fed by the River Meinam. The floating houses were built of bamboo, and looked very pretty.

"Post-office first, eh, Jack?"

The young fellow's eyes sparkled and his heart beat faster."

A Bangkok boatman was engaged, just as one engages a gondolier in Venice, and he was directed to take them to the post-office.

There were several letters for Walter, but none for Jack.

Poor fellow, his heart seemed to sink into his boots, and he could scarcely lift his feet, for they suddenly became heavy as lead.

They climbed down the ladder which led from the post-office to the boat, and Walter gave orders to go to the American consul's residence.

Then he began to examine his letters. He saw one post-marked Naples, and that he opened first.

It was from Amy Cottrell, and enclosed one for Jack from Beatrice.

What magic there was in that letter!

All his heaviness vanished, and he was elated until it seemed that he could fly over the houses.

The American consul was away from home, sick with one of those fevers which are prevalent in the city, and the affairs of the Americans were entrusted to the English consul.

He welcomed the Endicotts, and warmly declared that a newspaper man was cosmopolitan, and should be welcomed by every nationality.

The consul insisted that the Endicotts stay with him that night, for the sun was setting and on the next day he would accompany them to the palace.

They were charmed with the hospitality, and learned much of the customs of the Siamese.

In Bangkok our friends got into trouble because Jack laughed when the sacred white elephant was passing the throngs who knelt in homage. Chapter IX

Indeed, they were arrested, and it might have gone hard with them only for the British consul, who was attending to the duties of the American representative during the latter's absence on account of sickness.

Being finally released our friends hurriedly left the Siamese capital, and having run across a jolly sailor, they induced him to accompany them.

So, before Tsiang was reached, Patrick Mulvany, of Cork, in the "tight little island" called Ireland, was engaged to accompany the Endicotts on their trip.

With Patrick Mulvany as general baggage-manager, and three Burmese as bodyguard, the party started north.

Walter kept along the banks of the Meinan River until he reached the town of Ayuthia.

The little caravan was to rest there a day and a night before proceeding farther north.

At a village a few miles east of Pragat, Walter found the people weeping and wringing their hands.

The interpreter, engaged at Ayuthia, found that for consecutive nights a tiger had visited the village and killed a child.

The first night a pretty young girl of five years, the daughter of one of the principal men in the village, had been taken.

The people knew the habits of the man-eater so well that they were sure he would come the next night.

To appease his anger, for they thought the visitation was as a punishment for some wrongdoing, they found an old man who was infirm and unable to help himself.

They carried the poor old fellow to the tiger's trail and left him as a sort of sacrifice.

But the royal beast passed him by and again carried off a young child.

Then a sick woman was taken out to appease the wrath of the beast, but she died of exposure, and the tiger wanted warm blood, so entered a bungalow and killed a young woman and carried away her infant child.

Such was the story told to the interpreter, who retold it in broken English to the Americans.

"Have you not hunted the tiger?" Walter asked, in wonder.

"No, for the evil one is in the tiger, and all our children will be eaten before we can ever kill it."

The people had really resigned themselves to the idea that the tiger was possessed by all evil spirit, and that its object was the destruction of all the young people.

"We will hunt the man-eater," said Walter.

"By the powers! we'll kill the cat, an' the skin shall make the squire the purtiest coat that ever kept out the snow," Pat asserted, with violent gesticulations.

Walter and Jack could not help laughing at the idea of keeping out the snow at the time the mercury was registering ninety-eight in whatever shade could be obtained.

A hurried consultation was had with those who had lost their little ones, and all agreed that the tiger came from a jungle to the east of the village.

"We will watch to-night --- eh, Jack?"

"I am ready, and I think the ball from my good Marlin will dispossess the evil spirit."

Pat had boasted of his great courage, and so Walter, winking at Jack as he spoke, suggested that the brave Irish sailor should follow the trail a hundred yards or so ahead of the others, to give warning of the approach of the jungle king.

Pat protested loudly against such a proceeding.

"Cause why? Sure, an' if I saw the baste comin' I should kill it, an' so rob the squire of the honor of it."

"Never mind the honor, Pat; I would rather you kill it than that it should fall to my lot."

"Bad cess to me if I should be puttin' meself afore such a brave gentleman as yer honor. Patrick Mulvany knows his place too well for that."

"Pat, you are afraid."

"Afraid, is it! Then begorra, I'll show yez that there's not a dhrop of cowardly blood in me veins. Arrah, what's that?"

"I only cocked my revolver," answered Jack; "I thought I heard the tiger coming."

Walter arranged his plans, and did not place Pat in the post of danger or honor.

Night came and the people of the village stayed in their bungalows.

Hour after hour passed; and no sign of the man- eater was manifested.

It was just breaking dawn, or, as the Buddhists would say, the dark hosts of the night were being driven away by the angels of the day, when Jack suddenly whispered:

"Hist! Something comes."

Pat again fell on his knees, and Walter, thoroughly angry, placed his pistol at his head:

"Get up, you coward, a act like a man, or I'll shoot you."

"Better be a live coward, yer honor, than a dead man."

"Hush!"

"Look out, sir!" whispered the interpreter. "The beast is making for you!"

Walter was warned only just in time, for as he turned he saw two great, gleaming, fiery eyes, and they were looking at him with all the savagery of hate.