Volume 1857

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/schooner.htm

W.L. Alden

Author(s)

W.L. (William Livingstone) Alden (1837-1908): An American writer and diplomat. Some e-texts by Alden.Link to Tarzan of the Apes

Intelligent apes.Edition(s) used

Alden, W.L. 1893. "A Darwinian Schooner". Pall Mall Magazine 1(4): 543-552. Modifications to the text

None. Original publication was illustrated, but copy obtained was too poor to reproduce the illustrations from.

"You're quite right, sir!" said the mate. "As you say, a man can't follow the sea for twenty or thirty years without meeting with a good many things that he can't explain, and that no living landsman will believe if you waste your time telling him about them. Once I came across a schooner that was manned by monkeys. There wasn't a soul aboard her except monkeys, from the captain down to the Jemmy Ducks, and those monkeys had fitted out that there schooner and gone a piratin' in her. What's the good of my telling that to any man ashore? I don't believe there's a man, except he's a sailorman, who would believe it if I took my Bible oath of it. And yet I saw that schooner with my own identical eyes, and what's more, I was aboard of her in company of those monkeys for eight mortal days, so I know what I'm talking about." A Darwinian Schooner

She was overrun with rats"It happened about ten years ago, or may be twelve -- I don't keep any private log-book, and I can't always remember when -- just when -- anything did happen. However, I was second mate at the time of a brig -- the Jane G. Mather -- bound from London to Ryo Jenneero with a general cargo. The captain's name was Simmons -- 'Old Bill Simmons' we used to call him, seeing as he has a younger brother, Jim Simmons, in the Mediterranean trade. He wasn't a bad sort, and the brig was a middling comfortable craft, barring that she was so overrun with rats that you couldn't turn in at night without battening down your blankets over your face to keep them from trimming your nose down to what was their idea of a ship-shape nose. We were strong-handed, having eighteen men all told before the mast, besides two mates and a bosen.

"We made a good run as far as the Line, and then we had baffling light winds and calms for the next three weeks. We were in about five degrees south, and Cape Saint Roque beating five hundred miles west, when we sighted this schooner that I'm telling you about. I came on deck that morning at eight o'clock, and the first thing I saw was a schooner under full sail about a mile windward of us, there being at the time a light breeze from the south, and not much more than enough to keep steerage way on the brig. The schooner was acting in a very curious sort of way. Her sheets were hauled flat aft, and every little while she'd come up in the wind and shake for a minute, and then she'd pay off on the other tack. Sometimes she'd lie close to the wind, and then again she'd fall off till she had the wind nearly on her quarter."

"'Either she's lost her rudder, or all hands have gone to breakfast and left her to shift for herself,' said I to the mate, after looking at the schooner for a little while."

"'She's deserted, that's what she is,' said the mate. 'We sighted her at daybreak this morning, and I've been watching her pretty close. There ain't a soul aboard her, according to my idea. Well! I'll turn in now, and I expect she'll run into us before eight bells if he don't keep a sharp lookout.'"

"About two hours later the captain came on deck, and I could see that he took a good deal of interest in the schooner. The breeze had died out by this time, and there wasn't hardly breath enough to fills the schooner's sails. She lay not half a mile from us, and we could hear her booms creak as she rolled with the swell that was setting in from the eastward. It was clear enough that she wasn't deserted, for we could see a lot of niggers, as we supposed, moving about her decks, though there was nobody at the wheel. All at once the old man says, 'Mr. Samuels! we'll board that schooner and see what is the matter with her. Take the port quarter boat and four men, and find out what she means by yawing all over the South Atlantic. Tell the captain that this ain't no Ratcliff Highway, nor no Playhouse Square, and a decent schooner ain't no right to be staggering drunk at this time of day.'"

"Old Bill was always fond of his joke. Once he towed the cook overboard for fifteen minutes, because he put too much salt in the grub. You see he thought the man would get enough salt in his system while he was soaking astern of us to make him remember to use less of it in his cooking. But it didn't seem to do no good, and it pretty nearly drowned the cook."

"Well, I sung out for the men to clear away the boat, and then we pulled over to the schooner. When we came close to her I saw that she hadn't any name on her stern nor anywhere else, and that what we had taken to be niggers were nothing less than big monkeys -- baboons was their correct rating, I believe. Nobody had the manner to heave us a line, but we had no trouble in boarding the schooner. The monkeys were crowded together, watching us over the rail, but keeping as grave and quiet as a lot of man-of-war's men. On the quarter deck, all alone by himself, was an old white-haired monkey, that we took to be the captain, as he afterwards proved to be. He was sitting on the skylight, and was a great sight too dignified to be seen watching us."

We pulled over to the schooner"We made the boat fast and all hands of us climbed aboard the schooner. The monkeys fell back quite respectfully as we came aboard, and I could see that they were a pretty dispirited-looking lot. The deck was all in a litter, and there was nobody at the wheel or at the look-out. At first I didn't understand that the schooner was manned entirely by monkeys, so I went straight into the cabin to see if there were any signs of white men, or even niggers aboard her. The cabin was as neglected as the deck, and there wasn't a soul below. So I came on deck again, and after telling one of the men to have a look in the fokesell, to see if there was anybody there, I went up to the old white-haired monkey and says, --"

"'We came aboard to see if you wanted anything. If so be as you are the captain of this schooner, perhaps you'll tell me if you need a navigator, or a carpenter, or anything of the sort?'"

"The monkey didn't say a word, but he bowed as polite as if he was a Frenchman. Meanwhile the other monkeys had gathered in a circle around us, and were whining in a mournful sort of way. Just then the men who had searched the fokesell came up and said that there wasn't a soul aboard of her except the monkeys, and that they were half dead of thirst. There were a couple of full water casks on deck, beside one that was empty. When the monkeys saw that I was going to knock the bung out of a cask they went wild with joy, and even the old white-haired chap condescended to follow me, though he didn't chatter, and didn't show any especial interest in having the cask breached. You should have seen those monkeys go for that water! The poor beasts must have been days without a drop, and not one of them had sense enough to knock the bung out, though they knew the casks were full of water. There were provisions enough aboard the schooner, for I had seen a bread barge more than half full of good pilot bread in the cabin, and I knew that there must be plenty more where that came from."

"'I'm thinking, sir,' said one of the men to me, ' that thishyer'll be a salvage case.'"

"'Right you are,' said I -- 'that is, if the captain takes that view of it. We'll go back to the brig and report now, and if it be so that he wants this schooner to be carried into Ryo, there won't be much difficulty about doing it. You see the man -- 'Liverpool Dick' was his name -- had been in two or three ships with me, and was as good a man as they make. So I could talk a little freer with him than a second mate can generally talk with the men."

"When I told old Bill Simmons that the schooner was deserted except for monkeys, and that she was in first-rate condition, provided he wanted to carry her into port, he said that if I wanted to take six hands and navigate her into Ryo I could do so."

"'Enough said,' said I. 'I'll get my sextant and dunnage and be aboard the schooner before a breeze comes up. I suppose you won't mind letting me have Liverpool Dick? He'll make a good enough mate for me.'"

"'Certainly,' says Old Bill. 'You'll probably beat us into Ryo, and we'll pick you up there. However, you'll have just to shove the schooner along, for if we do get there first I can't wait for you, and I'll have to ship another second-mate and half a dozen men. You know what owners are yourself. They can take a moderate-sized lie alongside sometimes, but it's a mighty hard job to get 'em to histe it in'"

"It didn't take me very long to get back aboard the schooner. I had Liverpool Dick with me, and three middling good men, and three Rainecks that Old Bill was glad to get rid of. We all turned to and cleaned the decks up, and the breeze gradually freshened from the eastward, we slipped on our course and by night we had clean dropped the Jane G. Mather. Dick and I chose watches. I gave him three men, and I took two, and the odd man was put in the caboose and told to cook, though he swore he had never cooked so much as an egg since he was born. We managed to get some sort of supper about six o'clock, and the first watch on deck falling to Dick, I turned in feeling pretty comfortable."

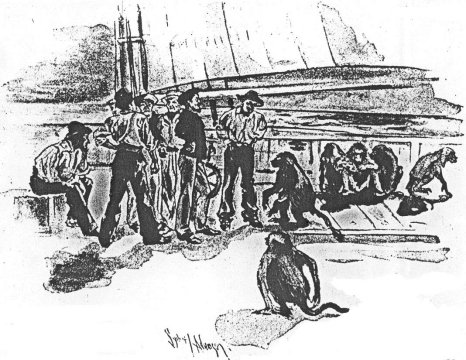

"The monkeys hadn't said a word since we took charge of her. They saw what we meant as soon as we came on board, and they turned out on the fokesell and left it to the men of their own accord, which showed that they knew the difference between sailors and monkeys. The old white-haired chap that was in command of them bunked by himself in the lee of the caboose, and the rest of them curled up under the weather rail about amidships, and were as quiet as you could wish. They all came aft at eight bells, so the mate told me, as much as to say that they were waiting for orders; but, getting none, they went to sleep again by the time I came on deck."

The monkeys all came aft at eight bells"The next day, the breeze holding fair, and there being nothing to do except to let her go along comfortable, I overhauled the whole schooner, searching for her papers, and not finding them. Dick and I talked about it, and I made up my mind that she has been carrying a cargo of monkeys -- for she had little else in her except ballast -- and that her people had got panic-struck about something and had deserted her. I found one or two things curious though. She had a big rifled gun lying down on the ballast, and about fifty breech-loading rifles stowed away here and there, where nobody would be likely to see them. Then she had two boats, and it didn't seem likely that a schooner of her size would carry more than two. If so, how did her people get away from her without a boat? I couldn't understand it, and no more could Dick."

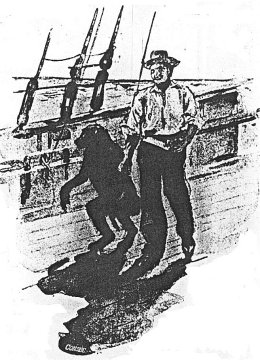

"The monkeys behaved well for the first two days. They were always on hand for their grub, which we served out to them regular; and they never grumbled -- at least, not so far as we could understand. The old monkey captain would now and the come and walk the quarter deck with me, never venturing any remarks, but just meaning, as I supposed, to show that there was no hard feeling. But the third day, Dick comes to me and says, 'It's my opinion, sir, that there's mischief brewing among them chaps.'"

The old monkey captain would now and then come and walk the quarter-deck with me"'Why so?' says I."

"'Well,' says he, 'they have been doing a lot of talking on the quiet among themselves, and the old man's got something on his mind, for he's altogether too bloomin' sweet-tempered this morning. He's laid into two or three of his people with a rope's end, and then he's been walking the deck with me, and bowing and grinning as much as to say that he considers me as much his superior as if I was a post-captain in the royal navy. I advise you to keep your weather eye liftin' while you're on deck tonight.'"

"'Why, what do you suppose they mean to do?' I asked."

"'What are they here for? Tell me that,' says Dick. 'This schooner wasn't never deserted with no crew. She sailed out of port with nobody but these 'ere monkeys aboard. That's my explanation of the thing'|"

"'Where were they bound to?' asks I. 'And what did they go to sea for?'"

"'They were going a-pirating, that's what they were doing,' says Dick. 'That's why she ain't got no name; that's why there ain't no papers of no kind aboard her; that's why she's in ballast; that's why she's got that big gun aboard, and all them rifles; that's why she's so strong-handed. Why, what do you think the old man dropped last night while he was a-calking in the lee of the caboose. He dropped thishyer knife, sir; and when a monkey takes to carrying a knife like that he means business, and you can just lay your last mag on that.'"

"It was a long clasp knife, with a sharp blade, made for stabbing and for nothing else. I didn't like the look of the thing; but I told Dick that his notion about the schooner having sailed with nobody aboard her but monkeys was rubbish. 'You saw for yourself,' said I, 'that they couldn't sail the schooner.'"

"'I saw that they didn't want to sail her for some reason or other,' says he. 'As to their not being able for to sail her, I have my doubts. Early this morning the man on the look-out went to sleep, and one of those monkeys, maybe the old man himself, went forrard and trimmed in the head sheets. The wind hand hauled round till, as you see now, it is pretty near abeam of us.'"

"'If they knew that much,' said I, 'we'll turn 'em all to, and make 'em do the rest of the work on this voyage.'"

"'Well, you'll see, sir,' said Dick, 'there's something in the wind, and we'll know what it is before long. I'm going to speak pretty plainly to the old man -- that is, if you don't have no objection.'"

"'None in the world,' says I. 'You might ask him where his papers are, and perhaps he'll tell you.'"

"The next day Dick told me that he had had a long conversation with the monkey captain, and told him we had our suspicions of him."

"'It stands to reason,' said Dick to the monkey captain, 'that you don't like have the command took away from you; but it was done for your own good. You're a passenger now, and all you've got to do is to conduct yourself as such. There's been altogether too much chin going on among the lot of you lately, and you'd better put a stopper on it just where you are. You needn't hope to catch us napping, and if you try any mutinous games you're bound to get the worst of it. Do you savey that now?'"

"The monkey grinned and bowed, swearing, as you might say, that he never had no intentions of no kind; and then he went forrard and took it out in cussin' his own people, as was quite right and natural."

"That very night, some time in the middle watch, I woke up, being in my bunk, and, being a very light sleeper, I heard someone moving in the cabin; and thinking that one of the men might be trying to steal on of my rum bottles -- for there was a dozen of heavenly rum in the pantry -- I slipped out and had a look. The lamp was burning, and there was the monkey captain stealing out of the cabin with a big chart, that I had marked her position on, under his arm. I sung out to him, and he dropped the chart, and took to smiling and ducking as respectful as you please."

"'I won't have none of this,' I said to him. 'You go forrard where you belong, and the next time I catch you here into irons you go.'"

"He didn't say anything, but he looked pretty mad, and slunk away without doing any more bowing."

"I told Dick of the affair when I relieved him at eight bells, and asked him what he made of it."

"'It's plain enough,' said he. 'Those fellows mean to seize thishyer schooner, and the old man wanted to know just what our position is. Have you got a pistol with you, sir?'"

"I told him I hadn't."

"'Then,' said he, 'my advice is that you load half a dozen of them rifles, and keep 'em where we can lay our hands to 'em if they're wanted. Those chaps mean bloody mutiny, and they'll begin before very long.'"

"I didn't much like the look of the thing myself. What did that monkey want with the chart? I told myself that, being a natural thief like all his sort, he just stole the first thing that came to hand when he got into the cabin; but why did he steal a chart when there was a bottle of rum standing in the rack on the table, with the cork already drawn?"

"When a monkey carries a big, bloody-minded knife, and comes into the cabin at night to steal a chart, there is something wrong; and I began to be half of Dick's opinion that there was a mutiny brewing.'

"However, the next twenty-four hours the monkeys were as quiet as could be. The monkey captain was full of his smirks and bows, and didn't seem to remember anything about his having been caught in the cabin the night before. He brought me and Dick a box of cigars that he had found somewhere -- and good cigars they were too! -- and his general idea seemed to be to make us believe that he was our best friend, and was ready to do anything to please us. The other monkeys kept watching him, and when they caught me or Dick or any of the men looking at them they'd grin as affable as a boarding-house keeper that comes down aboard an incoming ship a-looking for boarders.

Another queer thing happened that morning. When we hove the log, the monkey captain came aft and watched us, and tailed onto the log line to help haul it in, as though he was anxious for a chance to show his goodwill."

"'He's got our position yesterday from the chart,' says Dick, 'and now he's going to depend on dead reckoning till he can get another chance at the chart. I wish I knew as much about navigation as he does. I'd get a second mate's certificate and get out of the fokesell the next time I get to London.'"

"Now it did seem impossible that a monkey could know navigation, but it did look as if this particular monkey knew what charts and log lines are for. The man at the wheel told me that he's seen the monkey looking into the binnacle to see what course she was steering more than half a dozen times, and it was the opinion among the men that he was the devil himself. However, nobody could help noticing that when the monkey-captain's back was turned the rest of the monkeys kept up a low conversation among themselves, and it was easy to see that they had something on their minds."

"'I'd give a good deal to understand the lingo of them chaps,' says Dick to me. 'It's my belief that they know they're nearing the Brazil coast, and that they mean to take possession of the schooner by the time we sight land. I wish I had a pistol with me; though I don't doubt they're intelligent enough to understand what a belaying pin says when it hits 'em over the head.'"

"We were about two days' sail from Ryo, according to my calculation -- that is, of course, if the wind held -- and I was coming around to Dick's opinion that the monkeys had some sort of traverse that they calculated to work, though I couldn't chime in with his notion that they had fitted out the schooner and meant to go on a piratical cruise. After thinking the thing over more than a hundred times I came to the conclusion that the schooner had been on the west coast of Africa for slaves. That was why she was in ballast, and why there wasn't any name on her stern, nor any papers of any sort to be found aboard of her. I said so to Dick, but he wouldn't agree with me."

"'That's all very well as far as it goes,' says he, 'but it don't account for her being manned by nobody except monkeys. How did they get possession of her? That's what I'd like you to tell me.'"

"'Suppose she was lying in the river, waiting to take her cargo of slaves aboard, and suppose all hands got blazing drunk, and suppose the shippers sent aboard a cargo of monkeys instead of niggers. How does that strike you?' said I."

"'What's become of the crew?' asked Dick"

"'Why when they got sober and saw the monkeys they thought they had the horrors, and they all tumbled ashore to get more rum, or perhaps to get a little quiet sleep in the barracoon.'"

"'And the monkeys, seeing their chance, got up the anchor and made sail on her and carried her clear across the Atlantic! Seems to me, sir, that your story is about as tough as mine, and has got too many twists and turns in it. No, sir, I stick to my first opinion. This schooner was fitted out by monkeys, and no men never had anything to do with her, except perhaps to build her. Well, I'll go below now, and if you should want me on the deck in a hurry just knock on the deck over my bunk. I shall turn in all standing, and I'll answer your call about as quick as you can make it.'"

"I had no occasion to sing out for the mate during that watch, for the monkeys were quiet as lambs, and slept all curled up together, every man Jack of them taking a turn with his tail around the neck of the next one. It was an unseamanlike way of proceeding, for if there had been a sudden call of 'All hands!' it would have taken those monkeys ten minutes to cast themselves loose. But I suppose they got their ideas of seamanship from the Brazilians, and what could you expect of them?"

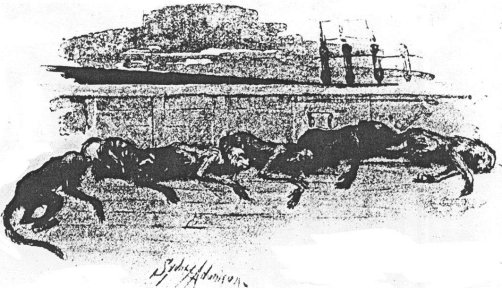

The monkeys slept every man Jack of them taking a turn with his tail round his neighbour's neck"The next day was Wednesday. I remembered it because it's my lucky day, though at one time it didn't look as if there was much luck about the day on that particular occasion. I noticed that every now and then one of the monkeys would lay aloft, for all the world as if he was looking out for land; and if you'd believe it, sir, one of them finally saw land, and reported it to the monkey-captain before any one of us white men saw it. I saw the fellow come down from the cross-trees and go up to the old man and say something, and then, after getting his orders, he went and told the rest of his people, and every one of them went forrard and began looking for the land, and chattering as if they were amazing glad that the voyage was almost over."

"The wind dropped about noon, and we were pretty near becalmed for the next twenty-four hours. I was getting anxious for fear the Jane G. Mather would reach Ryo before we did, in which case, as the captain had said, he wouldn't be able to wait for us, and I would lose a mighty good berth as a second-mate. At twelve o'clock I turned in, telling Dick to knock on the deck in case he should want me; and, remembering what he has said the night before about turning in all standing, I thought I would do the same, not knowing but what the calm might be followed, as it often is in those latitudes, by a sudden squall that might be more than the schooner wanted."

"I was sound asleep, and dreaming that I had come into a big fortune and had bought a big farm, stocked with elephants and codfish, somewhere down in Devon, and was going to raise cigars ready made, when Dick hammered on the deck with his boot heel, and woke me in a hurry. There was a tremendous row going on over my head, and my first idea was that we were going to be run down by one of those big French liners that are for ever running into other people along the South American coast; but before I could get on deck I heard Dick cursing and the monkeys snarling, and knew that he was having a fight with them. So I caught up a couple of rifles, which was about all I could carry, and was on deck inside of five seconds. The first thing I saw was that there was nobody at the wheel, and that Dick was backed up against the weather rail and fighting with all hands of the monkeys. They were jumping on him with their naked hands and feet, and trying to tear him limb from limb, and he was laying into them with a belaying pin as if he was mate of an old-time Black Ball packet breaking in a crew of packet rats. So far as I could judge the fight was a pretty equal thing, and Dick was keeping his end pretty well up. He had laid out half a dozen of the monkeys, but for all that they were full of pluck, and their captain, who kept a little on the outskirts of the shindy, kept encouraging them, and keeping them up to their work."

"I didn't wait many seconds before I got to work. I put a bullet through the monkey captain first of all. Then I fired promiscuous like into the middle of the muss; and then, using the rifle as a handspike, I let them see I didn't intend to allow no nonsense aboard of my schooner. They didn't stop to argue. Some of them went overboard; some went aloft; some laid out on the jib-boom; and the rest tried to hide wherever they could. In less than a minute the decks were cleared, and things were quiet again."

"It seems that the monkeys had made a sudden attack on Dick when he was least expecting them, and for a little it looked as if he might lose the number of his mess."

"'You see, sir,' he said, 'it's just as I told you. Them devils tried to seize the schooner; and I will say this for 'em, that they did it in a way that showed a good deal of savey.'"

"'Are you hurt?' I asked; for I could see there was blood on his face.

"'Only a bite or two, and a few scratches. Nothing of any account,' he replied. 'You see, they didn't have any arms. If they'd had knives like the one the old man dropped, it would have been all day with me. They'd have cut me into fine slices before you could have got on deck.'"

"'Where are all the men?' I asked. 'Where's the man at the wheel?'"

"'He's gone overboard, sir,' said Dick, 'with his throat tore open. One watch of them monkeys attended to him while the other watch was trying to do the same for me. The rest of the men is hiding in the fokesell, according to my idea, and I'll just take a handspike and go have a talk with 'em.'"

"I went along with him, and we found that the hatch had been clapped on and made fast, so that not a man in the fokesell could get on deck. All the men were below, including the man who had been on the look-out, and who had jumped down to rouse the rest of the men when he saw what the monkeys were up to. The men were mighty glad to be released, for there wasn't any air coming into the fokesell except where the hatch was off, and the night was a middling hot one. In about an hour more they would all have been suffocated, which is probably what the monkeys were expecting."

"Of course it was all hands on deck for the rest of that night, for we didn't know what new game the monkeys might try; but we heard nothing of them until daylight. About eight bells in the morning watch we got a slant from the eastward, and before noon we were in the harbour of Ryo."

"The monkeys kept out of sight, so far as they could, until we were close in with the shore, when they all went overboard; and when they reached the land they bolted for the woods. Dick was not in favour of letting them go, but said they ought to be put in irons and tried for mutiny and murder, but I told him that it would save a lot of trouble for us to be well rid of them before handing the schooner over to the consul. I went with the men aft, and told them that the least said about the monkeys the sooner we'd get our salvage money; and they all swore they wouldn't say a blessed word about it. No more they did. We told the consul that we picked up the schooner derelict, without a soul aboard of her; and he took our depositions, and did the usual thing in such cases, which, as you know with being told, was to keep us waiting for our money for the best part of a year, and then pay us about a tenth of what we ought to have had, saying that the rest had been used up for expenses. Oh! I don't blame him. It wasn't his fault; but that's what always happens when one of these 'ere Admiralty courts gets its lines made fast to a salvage case."

"Nobody ever found out who that schooner belonged to, or where she has sailed from, or what he name was, or anything about her."

"What is your opinion, sir? I've given you the straight facts. There was a schooner manned by monkeys, and nobody else. How did it happen? That's what I never found out, and what nobody ever will find out, in my opinion. I don't expect you to believe the yarn, though it's the gospel truth. I never found but one man who believed it, and it turned out that he was a lunatic at the time, though he was generally supposed to be only what they call a philosopher."

The End

BACK

TO COVER PAGE

BACK

TO INDEX

Comments/report typos to

Georges

Dodds

and

William Hillman

![]()

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL &

SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

other Original Work ©1996-2007 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.