Volume 1888b

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/regen3.htm

| BOOK I - The Island | |

|---|---|

| Chapter I. | The Primitive Norm |

| Chapter II. | Conscious of His Manhood |

| Chapter III. | The Word of the Book |

| Chapter IV. | Lesson and Labor |

| Chapter V. | The Voices of the Past |

| BOOK II - The Ship | |

| Chapter VI. | The Baseless Fabric |

| Chapter VII. | The Joy of Freedom |

| Chapter VIII. | Cast up by the Sea |

| BOOK III - The Revelation | |

| Chapter IX. | Latent Passions |

| Chapter X. | Hearts Awakened |

| Chapter XI. | The Conscience Quickened |

| Chapter XII. | The Ship on the Horizon |

| BOOK IV - The Coming of the World | |

| Chapter XIII. | The Long Search |

| Chapter XIV. | Past and Present |

| Chapter XV. | Accusation and Admission |

| Chapter XVI. | Confronted |

| Chapter XVII. | The Woman's Plea |

| Chapter XVIII. | Divided |

| Chapter XIX. | The Man's Failure |

| Chapter XX. | The Repentance That Came Too Late |

| BOOK V - Abandoned | |

| Chapter XXI. | The Resurrection |

| Chapter XXII. | Unavailing Appeal |

| BOOK VI - The New Life | |

| Chapter XXIII. | A Great Purpose |

| Chapter XXIV. | A Promise Broken |

| Chapter XXV. | United |

BOOK V - ABANDONEDThe little island lay quiet and still in the brilliant morning. No footfall pressed its bosky glades; beneath the shadows of its spreading palms no human being sought shelter from the sun's fierce rays; no human voices were echoed back from its jutting crags; no human figures flashed across its shining sands. Soundless it lay save for the cry of the bird and the rustle of the gentle wind across its hills. For well-nigh thirty years it had not been so abandoned. Two days past it had resounded with the cries of men scaling its heights, crashing through its coppices, calling a name, beseeching an answer. Two days before great ships had drifted idly under its lee. It had been the center and focus of great events. Now it lay desolate, alone. Chapter XXI

On that morning the tide, which had drawn away from it through the long night, had turned and was coming back. The onrush of the water spent itself upon the barrier. Within the lagoon it lay placid, rising gently inch by inch in mighty overflow. A watcher, had there been one, would have seen at sunrise the still waters of the lagoon broken by a ripple; a keen eye might have noticed at the base of the cliff where it ran sheer down into the blue a dark object moving beneath the surface. The eye could scarcely have become aware of its presence before the waters parted. A little splash, and a head rose, dark-crowned, white-faced. There was a sidewise wave and shake of the head and a pair of eyes opened. The blue of the water was lightened by flashes of white arms. As the body rose higher under the impetus of strokes vigorous yet graceful, it could be seen that it was that of a woman.

With ease and grace the figure swam along the base of the cliff until it was joined by a jutting spit of sand which widened and widened into the great strip of beach that ran around the island. Upon this sand presently the shallowing of the water gave the swimmer a foothold. Progress ceased. With eyes haggard, yet keenly alert, the sea, the shore, the beach, the cliffs, the trees were eagerly searched. The long glances revealed no other person. Then the head was turned, and the ear listened for sounds, and heard no human call. The look of apprehension faded into one of dull relief.

Walking now, the woman in the water made her way toward the sand. Very white she gleamed in the full warm light streaming from the risen sun against the background of the dark, black rock. The water dripping from her exquisitely graceful limbs, she looked a very nymph of the sea as she stepped out of the shallows at last and stood above the high tide line, poised as if for flight upon the hard and solid shore. Again she threw about her that quick, apprehensive look. Again she paused to listen. Reassured in that she heard and saw nothing but the bird's song, the wind's sigh, the wave's splash, she ran swiftly toward a blacker opening in the dark rock. She gleamed whiter still in the entrance for a moment and then disappeared. She came forth presently, still unclothed, a look of dismay on her face.

She had many things to do, much to occupy her mind, but the first duty that lay to her hand and the first instinct which she followed was that her naked ness should be covered.

Still warily watchful, still keenly alert, still fearful apparently of interruption or observation, she ran across the beach, her movement as free, as graceful, as rapid as she had been Atalanta herself, and disappeared under the trees. The whirr of birds disturbed might have marked her passage.

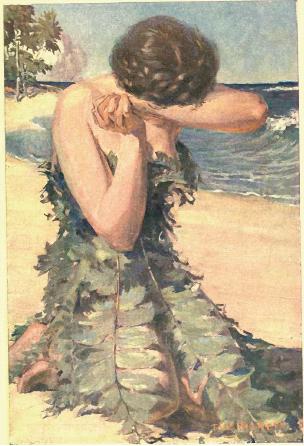

After some time she appeared on the top of the high, bare hill that crowned the island. She had improvised for herself a covering out of three or four great fern leaves, soft and pliable, which she fastened with palm fibres from shoulder to knee on either side, her bare shoulders rising from the rich greenness like a white corolla from its verdant calyx. She went more assuredly now, partly because of the fact that she was clothed and partly because her first rapid survey of the horizon revealed the fact that the ships were gone.

Determined to make sure, she descended the hill rapidly to the landing place of the day before. Still searching, she found nothing. She was glad that this was so, and yet, when the full and final realization came upon her, she knelt down on the shining sand, hid her face in her arms, clenched her hands and gave way to voiceless agony. Sometimes there is nothing so terrible, she realized, as prayer granted, as desire accomplished, as undertaking brought to conclusion. The awfulness of success was upon her in that hour. Her ruse had worked. Her object had been attained, yet the achievement gave her no pleasure, on the contrary!

Her own acts had parted her irrevocably forever from the world and the one man in it who was the world for her. He was gone. She who had made him had sent him forth among his fellows. She had sacrificed herself, buried herself alive for him. She felt as a mother might who experiences birth pangs and knows that with every throb of tearing anguish her own life ebbs away, passes into the new life which she ushers into the world and gives to men.

She had sacrificed herself, buried herself alive for him.She had had long hours for thought in those two days in that cave whose mouth the waters hid. She had schooled herself to face light and life without him when she emerged from her cunning hiding place. She had waited the long period in order to make absolutely certain that they all would be gone. And yet, despite herself, a little gleam of hope, a bare possibility that he might still be there, had ling ered in her soul and leavened the awfulness of her grief. Now that hope was gone. It had disap peared even as the ships had disappeared.

She had been bitter against him. Her soul had revolted because he had failed. She had told herself that he was not worthy of her. She forgot these things in that profound and desolate moment. She knew only that she loved him. When she could think of other things than of him the mere bodily presence of the man, the look of him, the sound of his voice, the pressure of his lips, the clasp of his arms she began to realize that as he grew older, unless she was so absolutely mistaken in him as to make all estimate of him a mockery, he would real ize the falsity of his view, the littleness of his action; and if he were in truth the man whom she could rightly love, his years would be one long regret that he had failed. What would happen when he understood that, when he came to the knowledge that she was indeed all that she had seemed, and that he had been nothing that he should? She knew, as she had written, that the man would never, could never, forget her; that wherever he went and whatever he did, she would be present with him; that she had stamped herself too indelibly upon his heart for any attrition with humanity, how ever close and persistent, to erase the image. He would come back, perhaps.

"O God!" she knelt down and lifted up her arms toward heaven, "bring him back," she prayed -- a few short, broken words, lacking the eloquence of long and studied petition, the appeal of the heart every throb of which is a prayer -- "bring him back to me!"

She thought that she would have had him back on any terms. She said that she had been mad, a fool, not to have taken him, not to have gone to him, not to have married him in any way, with any conditions, under any circumstances. All her thoughts were merged in one great passionate longing to be with him.

For the first time in her life the pangs of jealousy tore her breast. She thought of him in the world with other men, with other women, young, handsome, a perfect god-like form and face of man, rich, the wildest romance with its charm and mystery to attract. His story could not be hid, neither could hers. The man would be courted, sought after, made much over, beloved. It would be enough to turn the head of a saint. How would he stand it? Would the recollection of her make him strong? Would that God in whom he and she both had trusted until this crisis came, lead him in the straight path? Would her purity, her sweetness -- stop! would he think her thus dowered and possessed? Not now, certainly, but every hour that took him farther from her would add to his knowledge and would tell him the truth, and these would help him.

Another thought came into her mind. His story would be known, and hers as well. The world was filled with adventurous men. Would not some of them come in search of her island? The officers of those two ships could determine accurately the situation of that island. It would be as easy for a navigator to find it as for a denizen of a city to go to any given street corner. People might come back to that island; not to seek her, for the world would believe her dead, but simply to see the place. Idle yachtsmen might find that an object for long cruising, and she would have to hide and hide. But would she hide? Would she go back to that world? Never, she said, unless he came to fetch her.

And then her thoughts turned again. Why had he gone away? Had she been he they could as soon have uprooted the island itself as torn her from it under similar circumstances. Had he been gone, she would have lingered and died on the spots that were sacred because there he had walked. If she had known that at that moment her Man lay fighting for life and reason in the cabin of the swift-moving ship, she would have understood better his absence. That he could be so stricken never occurred to her.

She had been mistaken in him doubly, mistaken when she thought he would rise to the test, and again mistaken when she thought that, having once fallen, he would not rise again. She did not know that he had come ashore in the gray of the dawn to seek her, to throw himself at her feet, to declare that all he had thought of her was as noth ing to what he thought of her then; that she was the sweetest, the noblest, the truest, the purest woman upon earth; that he could not live without her; that she must take him back into her heart, give him the place which so briefly he had enjoyed, if she did not wish to see him wither and die under her displeasure like an uprooted palm, a torn-down tree.

She did not know that when he had called her name at the mouth of her cave and had at last entered and not found her, how terrible the shock had been to him. She had not seen, she had not heard, she could not know, how he had been stricken down when he caught sight of the little heap of clothes which she had laid out upon the beach to make the searchers think that she had gone.

And it was well for her that these things were hidden from her, for had she believed him suffering, dying, and she not there, the separation would have been more unendurable than it was. She pictured him, not happy away from her, overwhelmed by her death surely, saddened beyond present comfort it must be, yet so occupied that insensibly his grief would be lightened by the only thing after all that makes life bearable in certain contingencies, and that is work. Work! She, too, had work to do.

She rose to her feet doggedly as she thought of that, and considered what she could do. She climbed the hill again. It was in part aimless, restless wandering, but it gave her occupation. Her eyes fell upon the ashes of the signal fire. She contemplated it as the spectre of some Hindu woman whose body had been burned upon such an affair might look upon her pyre. It was she who had lighted the beacon. Her hand had called the world to her side. She thought how he had begged her not to do it, how he had declared himself content and happy to live with her alone the world forgetting, by the world forgot! For the second time she broke down completely. She buried her face in her hands, her body reeled and shook with sobs, the tears trickled through her fingers. Was she to be forever unequal to the separation? she asked herself at last.

She must make another beacon, she decided at last; that would give her something to do. And then it came to her that they had taken away the flint and steel. She had no means of lighting it. That realization developed other thoughts. Her Bible was gone; her clothes were gone; her toilet articles, her scissors, her watch, her knife. They had taken everything. They had left her nothing, absolutely nothing. What did it matter? She could dress herself with fern leaves and make shift to bind them about her with cords that she could plait of the grass which she could tear with her sweet strong hands. And what did it matter what she wore? There was no one there to see. But for the age long habit of modesty, she would have torn away and thrown aside the makeshifts that fell from her shoulders.

She saw herself reduced to the life of the mere animal. She had nothing but her hands, no tool or implement of any sort. Who had defined man as a tool-using animal, she wondered. She wished that she had buried or hidden some of the things before she took that determination to retreat to that cave which she had discovered on the day that she had discovered that he loved her and that she loved him. She had stood there in the water hesitating as to whether to go out or to come back. She had utterly forgotten the cave until, the tide being out, a backward glance from the low level at which she stood had disclosed the black and narrow opening. And then without a thought she had decided on her course. She had gone back and written in the Bible with the lieutenant-commander's pencil, which unwittingly she had retained, and then she had plunged into the cave with enough food to last her for the two days.

She rehearsed it all and came to the conclusion that she must eat unless she would really die. To eat, to sleep, to dream -- these were all that were left her. She wondered if she would lose the power of speech. She wondered if she would descend in the long years to that low level from which she had up lifted him. She felt that perhaps she would go mad. She threw herself down upon her knees again and prayed once more, this time that God would enable her to keep her reason, so that if the man did come back she would be ready for him.

Quieter after a while, and a little comforted, she rose and made a circuit of the island. She must make sure that no one really was ashore. She went last of all to the cave that had been his. She would choose it for her own now. It was reminiscent of him. In her thoughts it would be like having him near her. She kissed the sand where he had lain so long.

So the dreary day dragged on until the night fell and sleep came to her wearied body and soul with its benediction of oblivion.

She slept late the next morning. In the first place, being upon the western side of the island, there was no flooding burst of sunlight through the open door to disturb her quiet slumber. In the second place, she was so worn out and exhausted, she had had so little sleep in the past three days, that imperative nature forced her into rest. She might have slept longer indeed but that she was awakened by a great cry, a human voice calling her name. She opened her eyes and saw within the dimness of the cave a human figure, vaguely white in the darkness. For one fleeting instant she imagined that it might be he, but that hope was dispelled as quickly as it had been born. She recognized the voice. It was Langford's. Chapter XXII

"Kate," he said, approaching her more nearly and bending over her, "are you alive, then?"

He reached down and touched her hand where it lay across the fern leaves on her breast. His touch summoned her bewildered faculties to action. Brushing his hand aside, she sat up.

" Mr. Langford, Valentine!" she exclaimed in a daze of surprise.

"You are alive and well?"

"Yes," she answered.

"Thank God!" cried the man. "We thought you dead. We searched the island. Where had you hidden? Why have you done it?"

She rose slowly to her feet and confronted him.

"You!" she said bitterly. "Why have you come back?"

"I don't know," answered Langford. "I can't tell what moved me. I was here on the island with the others. I searched with the rest. I know that no foot of it was left unvisited. Every crag and cranny, every thicket and coppice, every tree, every cave and rift in the rocks was examined over and over again. We knew that you were gone, and yet I could not believe it. Yesterday afternoon I parted from the cruiser. I did not bear away for this island until it was too dark and they were too far away to see what I would be about, and then I came back here at full speed."

"Why did you come?"

"I don't know. I was not satisfied. It seemed to me that I must come back and search again. I could not believe it possible that you were dead, really dead. Something in my heart at any rate brought me once more to see the place where you had lived, if no more than that. We made the island early in the morning. The yacht lies yonder. I came ashore alone a moment since and some kind Providence led me first of all to this spot. I entered the cave. I saw you lying there in the cool darkness. I thought you dead at first. Then I cried to you and you moved. And then I touched your hand. O Kate, thank God I have found you!"

"Where is he?" said the woman. "Why didn't he come back?"

It was a cruel thing to say, but she could not more have helped it than she could have helped her breathing. Not to have said it would have killed her, for if Langford's love could turn him back, what could be said then of Charnock's. Langford was pale and haggard. He, too, had suffered. He was paying for his sins. He was expiating them and feeling it, although the expiation was not helping her.

"What of him?" she asked insistently.

"What matters about him?" he said bitterly. "He had his chance. He failed to grasp it. He's gone."

The man did not tell her that Charnock had been carried away a senseless log, bereft of power to think, or speak, or move, or feel by the shock of her departure.

"Once," said the woman, "you had your chance in the cabin of that very yacht out yonder, and you failed to grasp it, and we separated."

"Yes," said the man, "I know that, I realize that now, and I came back, I have come back now to take my chance again."

"And so he may come back," said the woman. "You sank lower than he."

"And I rose higher the other day upon the sand."

"You did, but not high enough. I believe in him. He will realize it, too," she went on, all the confidence of her hopes springing into life again and giving force and power to her voice and bearing.

"And you condemn me for that one mistake?" said the man.

"No," returned the woman, "neither will I condemn him for that one mistake."

"But he is gone, I tell you."

"And he will come back, I know."

"He thinks you dead."

"So did you."

"But I came back, not he."

"You were your own master," said the woman swiftly. "You could go where you pleased. He was subject to the decision of others. I trust him still."

"And you don't trust me."

"I trust you enough, but I don't love you."

"O Kate, think! There must be something in what I feel for you to move you. I did not know what it was. I did not realize it. I came back in the first place as much because I had been a blackguard and a coward and wanted to set myself right in your eyes as because I cared for you, but every hour of search made me know my own heart, and since I have seen you, since I see you now, there is nothing I would not do for you, nothing I would not suffer for you. This isn't any expiation or amendment or anything now, but because I am a man, and love you, I want you. I want to make you happy. And I am the one man in the world that ought to want you and want to make you happy. It is for that I have come back to you."

"How terrible are the arrangements of blind fate," said the woman. "I must believe what you say. You awaken my pity, my tenderness, my consideration, but these are all. He is not by to hear, and therefore I will tell you unreservedly, for you deserve the truth, that just as you say you love me, nay, then, just as you do and more a thousand times, I love that man. It would be a crime, a sin, a bodily profanation, a mental and spiritual degradation to which the other" -- he knew to what she alluded as she paused -- "were nothing, if I should come to you with my whole heart and soul given to the man," she threw her hand out in a great sweeping gesture, "yonder out at sea."

"But he doesn't love you."

"O yes, he does. Not as I would be loved, I admit, not as, please God, I shall be loved by him, but he loves me. He doesn't know; he doesn't understand. Wisdom will come to him and he will come back."

"It might be so," admitted the man reluctantly. "I came back. But he believes you dead."

"And did not you when you searched for me during those three years?"

"No," answered Langford, "I had a confident hope that somewhere you were alive."

"And will he not have that hope, too?"

"I cannot believe it."

There was a long, frightful pause. The woman sighed deeply.

"It may be as you say. It may be that we are separated forever. It may be that I shall never look upon him again, or he upon me, but that makes no difference. I do not love you. I cannot love you. If he is dead, I shall love his memory until I meet him, if so be I may be found worthy of that, and I will keep myself for him. No other man shall have what belongs to him."

They had stepped nearer the entrance of the cave, which was a spacious one, as they spoke. The beauty of the woman in that soft light was so in tense that it cast over Langford a spell. He heard the sound of her voice, but did not heed what she said. Suddenly he caught her in his arms.

"Kate," he cried, "we are alone here, and I am master. That is my ship yonder. I can have you bound hand and foot and take you aboard of her. I will say that you are mad, that I am taking you back to the United States to your friends. You must come back with me. I can't let you go."

"Valentine," said the woman quietly, "if you do not instantly release me, I will kill you where you stand. You don't realize how strong I am. See!"

With a quick, sudden movement she caught his arms with her free hands and literally tore them apart. To her lithe and vigorous body she added spirit and determination which made her indeed more than a match for the slender, somewhat broken man before her.

You see!" she cried. She stood between him and the doorway, one hand outstretched, the fingers open. "I could kill you before you left this cave. You told me that you had sent your men back to the ship and that you were alone upon the island, and I could hide where I hid before and they would find your dead body here upon the sands. That would be all."

"Kill me if you wish," said the man recklessly. "I don't care. Perhaps that would be the better way."

"No," said the woman, "I respect you too much for that."

"Respect me?"

"Yes. You have shown me what you are by what you have done, all but this mad action of a moment since, and I can understand that, my friend, for I too love, and it seems to me that I would brook anything, everything, for one moment like that you fain would have enjoyed. But we are not children, neither are we savages to act like beasts of prey. I forgive you, I trust you." She came close to him and laid her hand upon his arm. "I respect you, I admire you!"

"Everything," said the man, "but love me."

"Everything but that," assented the woman quietly.

"I shan't offend again," returned Langford. "Neither by force nor persuasion can I effect anything. Kate," he said after another pause, "come back to the United States or to some civilized land. The world is before you. I will land you where you please and give you or lend you money enough to enable you to go where you like. You shall be on the yacht to me as my sister."

"It can't be," said the woman. "Don't you see that I can accept no favors from you?"

"But no one need ever know. I will discharge the crew of the yacht in some South African port. They will scatter . . ."

"God would know and I would know, and when I see the Man, my Man, again I would have to tell him. It would make it harder for him, harder for me. And I don't want to go back. I will wait here for him."

"Kate," said the man impulsively, "it was ungenerous of me not to have told you before. They took him away from the island senseless, raving with brain fever. He collapsed, stricken as if dead, on the sand by that little heap of clothes and the Bible which bore your message. He thought you dead. He left the ship in the early morning to seek you. The shock was too much for him."

"He loved me, then," said the woman.

"Yes," said Langford, wringing the admission from his lips, "he loved you enough almost to die for you."

"But he is not dead. He was not when you left the cruiser?" she cried in bitter appeal, her hand on her heart.

"No, they signaled to me at noontime in answer to my inquiry that the doctor thought he would finally pull through, although it would be a long, terrible siege; but if he dies, Kate, if I go back and find that he is dead and come here . . ."

"Don't come back," said the woman. "Don't tell anyone that I am here. Let no one ever come back unless the promptings of his heart and the leading of God should bring him to me."

"Is this your final, absolute decision?"

"My final and absolute decision. Nothing can alter it, nothing, absolutely nothing."

"O Kate!"

"Don't," said the woman. "It is useless and only breaks your heart and wrings mine. Now, you must go. No one has seen you from the yacht. This cave is sheltered from where she lies. No one need know that you have found me. Indeed, I want you to give me your word of honor, to swear it by all that you hold sacred, that you will never tell anyone, much less him, that you came back and found me alive."

"You set me a hard task," faltered the man.

"But I am sure," continued the woman, "it is not too hard for you to accomplish. Come, you have said you wanted to make amends. That is all past now, forgotten and forgiven, but if you really would make me happy, you will promise what I say."

"And what is that, again?"

"On your word of honor as a gentleman, by all that you hold sacred, you will never mention to a human soul that you found me here alive."

"On my word, by all that I do hold sacred, by my love for you, Kate, I will not speak unless in some way you give me leave."

"So help you God!" said the woman solemnly.

"So help me God!" replied the man with equal gravity.

"And now you must go."

"I have one request to make of you, Kate, before I go," said Langford.

"If I can grant it, you may be assured I will."

"It is very easy. Will you stay in this cave for two hours?"

"I have no watch," said the woman, "but I will guess at the time as best I can."

"Then," said the man, "go down to the beach. The yacht will be gone."

"Valentine," said the woman, "you don't mean to stay here on the island?"

"I would stay gladly," returned the other, "if I thought that I would be welcome, but I know that cannot be."

"I will wait," said the woman. "Good-by!"

She extended her hand to him. He seized it in his own trembling grasp and kissed it. He remained a moment with his lips pressed to her hand, and she laid her other hand upon his bended head. He heard her lips murmuring words of prayer. He released her hand, stooped lower, laid something at her feet, turned and resolutely marched out into the sunlight.

The woman lifted her hand, the hand that he had kissed. It was wet with tears. The man had left her with a breaking heart. She sat down upon the sand to think her thoughts during her two hours wait. Her bare foot touched something metallic. She bent over and picked it up. It was his watch.

He had placed it there. The simple kindness, the spontaneous generosity of the little action, moved her as had not all his pleas, and she mingled her own tears with his upon her hand.

It was a long wait, and yet he had given her much to occupy her mind. His visit had saddened her, but, more than that, it had gladdened her. There was comfort, and any woman would have taken it, in the thought that Langford had come back to her. There was comfort, mingled with apprehension, in the thought that in the still hours of the morning her companion had come ashore, she divined, to sue for her forgiveness. There was more comfort in the thought that he had not left her voluntarily, but had been taken away helpless, ill. There was most comfort in the thought that his belief that he had lost her had almost killed him.

There was dismay and sick apprehension in the thought that he was ill and she was not there. And yet despite herself a little gleam of hope sprang up in her heart. He could not die, having been so preserved for, lo, these many years. Some fate had been marked out for him, some Providence would watch over him, and some day he would come back over the sea her Man!

She had guarded against any outside influence. She had Langford's word, his solemn oath, that under no circumstances would he tell anyone that she was alive, least of all the man of all others she would fain have know it. But he would come back. He could not live without once more visiting the island, and when he came back, he would find her waiting for him.

She looked at the watch after a while and found that more than two hours had elapsed, nearly three. The latter part of the time had fled swiftly in thoughts of him. She was hungry and thirsty, too. It was noon. She went out on the sands. The yacht was nowhere to be seen. She could not yet have got below the horizon. She divined that he had sailed around the island and away in that direction.

There was a pile of boxes and things on the sand above the high water mark. She stepped toward it and opened one of the sea chests. It was filled with books and papers, a strange collection. He had ransacked the yacht for her. Another chest contained provisions with which she had long been unfamiliar. There were toilet articles, pieces of cloth, writing paper, pencils, a heaping profusion of all that he fancied she might need, that might afford solace and companionship to her and alleviate the loneliness of those hours. In her heart she thanked him, and lifting up her hands, she blessed him again. He had made life possible and toler able to her. She could write, she could read, she could sew. And all this while she could hope and dream.

BOOK VI - THE NEW LIFELate springtime in old Virginia. The climate was not unlike that of the island during the cooler portions of the year, thought the man standing on the porch of the high-pillared old brick house set upon a hill overlooking the pale-green waters of Hampton Roads which stretched far eastward past Newport News and Old Point Comfort to the blue of the Chesapeake, and far beyond that to the deeper blue of the ocean. Back of him a thousand leagues of land, and more than a thousand leagues of sea, intervened between him and the object of his thoughts. Not for a day, not for an hour, scarcely for a moment even, was that island out of his mind. There was pleasure and pain in the recollection of it. Upon the man's face a stern melancholy had set tled. Not the melancholy of ineptitude and indifference, not the melancholy that made him do nothing unmindful of the large issues of life in which he had been suddenly plunged, not the melancholy that paralyzed his activities, but the melancholy that comes from the presence in the heart of an abiding sorrow that neither time nor change nor occupation could uproot; a melancholy that came from the sense of bereavement ever growing more keen and more poignant as the period of bereavement lengthened, and which sprang from a consciousness of imperfections and failures for which no after achievement could atone. Chapter XXIII

In some circumstances there is comfort in a deathless memory, in the recollection of a presence that has passed. There is solace in the dream touch of the vanished hand, in the heart echo of the voice that is stilled, if when the hand was warm and the voice thrilled in the hollow of the ear, nothing was done which could impair the sweetness and the purity of the remembrance afterward. But this man had slain the thing he loved. Guilt, as of a murderer, was upon his soul. He could not throw it off.

Had he been less a man, he would have sought oblivion by following the path to death upon which he fancied she had shown the way. When he came to his senses in the cabin of the ship, weak, worn, wasted as one who had gone through the very valley and shadow of death itself, and they had told him, in answer to his eager questions, the truth which he had divined ere he had been stricken down, his first conscious resolution was to live worthy of her remembrance. He had failed awfully once, and before he could make amends she had vanished, but somewhere beyond the stars he believed she knew his present purpose. Unless men's hopes for the future were all a dream, unless their desires and aspirations were like the baseless fabric of every other vision, he knew that she would know. He would show to her and for her memory's sake that he could be a man. To die would have been far better for him, but he would live on, live on for her. He would do things in the world, and couple her name with them. Men should know what she had been through him, he would cause her to be remembered, and some day, when he had worked out his punishment, howsoever long it should please God to require it of him, he would be worthy of her in that high place to which she had gone.

It was that, and that alone, which enabled him to endure the consciousness that he had killed her, the good being he loved, the sweet being he adored, the pure being whom he would fain have cherished -- too late! He lashed himself with that thought as the devotees of old scourged their bodies until the blood ran, in some futile effort thus to purify their souls. As it were he wore next to his skin the hair shirt of the ancient martyr, allowing it to chafe his very vitals. And yet he lived to accomplish his purpose.

It had not been difficult to establish his rights. Whittaker and the chaplain, armed with the depositions, had taken the man across the continent when the ship had been put out of commission at San Francisco, and presented him to his uncle, the Charnock in residence in that great house on the Nansemond shore overlooking that estuary of the James by Hampton Roads. The old man, childless and alone, had welcomed him gladly. The newcomer was of the Charnock blood. It was a strange moment for the islander when they took him into the great drawing-room and showed him the pictures of his father and of his mother. He was the living image of the man, tempered with some of the woman's sweetness. This remarkable likeness -- indeed he was not unlike his uncle as well -- coupled with the material proofs, the ring, the Bible, the evidence of the ship, together with what was known, removed every lingering doubt from the minds of those most concerned.

The family was reduced to those two, the uncle and the nephew. The old man formally and legally recognized the relationship and offered to transfer the property rightfully his, which since the discovery of coal had increased enormously in value, to the newcomer, but Charnock would have none of it then. He recognized his unfitness to deal with such things. If the older man would retain it, he could give it to him at his death. Meanwhile he could teach and train him how to use it. Bereft of his one guide, his one inspiration in life, he would need wise counsel and careful leading indeed.

In addition to the formal recognition, the older man legally adopted the younger and constituted him the heir to his own property, which was almost as extensive and as valuable as that which rightly belonged to the nephew. And then, these formalities being completed, the lieutenant-commander and the chaplain, summoned elsewhere by their duties, bade the two farewell and left them.

Charnock could not have fallen into better hands. Education was his first requirement, and he applied himself to it with a fierce energy and a grim determination which presently, from the splendid foundation which had been laid by the woman, enabled him to progress sufficiently to take his place and hold his own with men and women. It was impossible to keep secret forever the details of such a story as his, especially when it was linked with a name once so famous and still remembered as that of Katharine Brenton, and it had been decided by Captain Ashby and Whittaker and the man himself that such portions of it as would suffice to explain his own presence and her fate should be given to the world. Upon the foundation thus afforded, romance builded. Charnock immediately became a marked man. He would have been a marked man in any event from the financial power that he possessed. His uncle's management had been wise and prudent, he had spent little and had saved much, so that Charnock found himself the possessor of vast riches in the form of available capital.

Among the first things that he learned was the power of money. Had he not been steadied by the memory of the woman, he would probably have learned it to his sorrow. As it was, he was almost miserly. He spent little upon himself. His wants were astonishingly few, and contact with the world did not develop extravagant ideas. Those were things which he was too old to learn, against which he had been anchored. He was saving what he had and what he could get for some great purpose, a purpose of help, of assistance in which he could com memorate her name, for which future generations should rise up and call her blessed.

He had long talks with his uncle about it. The old man would fain have had his nephew marry and carry on the ancient line. Delicately, tenderly, he broached the subject after a time, but the suggestion met with absolute refusal. Women interested Charnock as men did. Indeed, his interest in his kind was intense. The intellectual stimulus of conversations with bright, intelligent people was the most entrancing result of his contact with the world. But none of them touched his heart. That was buried on that gemlike island in the far-off sea.

He was a man of unusual force of character, prompt and unyielding decision. His uncle had not lived his long life without being able to estimate men. He recognized very early in the undertaking the futility of argument, and though he tried finesse in the presence of the wittiest, the cleverest, and most beautiful women of Virginia and elsewhere, for the two traveled throughout the United States, welcomed everywhere, his efforts were all unavailing. There was more than one woman who would gladly have accepted the man's suit; whom, if he had wooed her ever so slightly, he could have won, but he was friendly with everyone and in love with none.

At the end of two years society gave him up as confirmed in his isolation and loneliness. He was not the less welcome, but he was no longer a matrimonial possibility, nor was he any more the wonder that he had been. New things engrossed public attention. The world presently took Charnock as he would fain have it take him, as a matter of course.

He did things slowly, not because that was his nature, but from an invincible determination to do things right. He made his plans deliberately, and had formulated an enterprise so comprehensive in its scope, so vast in its outlay, and with such infinite possibilities of help to the poor, the wretched, the down-trodden classes of society, that, when the fore- shadowings of it were announced, people stood amazed. An undertaking so great was not within the power even of Charnock. His resources were utterly unequal to it, but he had enough to make a magnificent beginning, and by devoting to it the whole revenue of his estate, and the estate itself after he died, gradually the enterprise would be achieved.

There was no necessity for secrecy about it. Indeed, with that simplicity and candor so unusual and so unconventional, which touch with the world had never been able to alter, he had spoken of his plans without reserve, and he had declared with equal frankness that what he was doing was in memory of the noblest and the truest of women to whom he owed it that he was a human being and not an animal.

Whittaker, of whose judgment he thought highly and with desert, was called from the naval service to be executive head of the great undertaking. The spiritual work was to be placed in the hands of the chaplain who had so endeared himself to the pro moter and deviser of it all. Charnock realized that these men who had known Katharine Brenton would enter more sympathetically into his views and could be depended upon to carry them out in case anything happened to him. He and his uncle and one or two others of excellent judgment whom he had met, were associated with the two mentioned to carry out all the founder s plans.

Now, this thing was not done in a corner. The news of it was carried over the United States and spread even to foreign lands. The world read it and marveled again. A newspaper carrying an account of it fell under the eye of a lonely man in San Francisco who had just returned from a long voyage in northern seas. The name "Charnock" caught his eye first, and then Langford saw the name of the woman he loved. He read with avidity, appreciating as none could better do than he from his trained business acumen the scope and yet the feasibility of the undertaking. He had wondered cynically what would be the career of the man in the United States. He knew the value, as did every business man, especially every man with large transportation interests like his, of the Charnock estate. He would have wagered that Charnock would lose his head as ninety-nine men out of a hundred would have done, and that, intoxicated by the sudden touch of the material world which was at his feet, he would have gone the usual pace; and he would have won his wager had it not been for the immortal memory of the woman they both loved, he felt bitterly enough. He had not followed Charnock's career. Committing his own large business interests to those upon whose judgment and integrity he could rely, he had gone restlessly about the world in the Southern Cross, seeking by change to drown his own sorrow, which was as deep as, even deeper than, Charnock's, because he knew that the woman he loved lived. He had to face the possibility that at any time others might discover that fact, and that Charnock among the rest would learn it, and then . . . It was that thought that drove him on, it was that thought that broke him down. He was a sick man, almost a dying man, as he steamed through the Golden Gate and landed from the yacht that spring morning. He did not care, he had nothing for which to live. His love for the woman had grown and grown until it had possessed him and transformed him. His expiation was indeed a fearful one, for there was no end to it but his death, and he felt that would be welcome.

He had to set his affairs in order, or he would have stayed at sea and let his life go out there, directing that his body should be sunk in the great waters which washed the distant shores where her foot trod. Indeed, when he was on the Pacific he seemed somehow to be in touch with her. A hundred times the order to steer southward to that gemlike island had trembled upon his lips, but he had held it back. He knew what that woman was; that her "Yea, yea" and her "Nay, nay" could not be changed by any power that he could wield, and so he had stayed away. And now he came back to San Francisco, a sick man and about to die.

He sat alone in his office in the great building and pondered over the account in the paper. He had been mistaken in the man. He was really worth while. He had amounted to something. He was worthy of the woman. If he had not sworn an oath, given his word. . . . He hesitated, smiling bitterly. The woman alone could release him. Should he sail down to the island with that paper and tell that story. He knew that he could not do it. He had not the strength. There was not time. He had waited too long. The army surgeons in Alaska had told him the brutal truth; that he had but a few months to live, and that if he had anything to do before he went out into the beyond, he would better do it quickly. No, he could not go down there and tell her and get released from his promise.

Yet how Charnock would revel in such news as he, and he alone, could give him! He loved the woman and he hated the man. He could not bear to think that the man should have what was denied him. He could not bear to think of the woman he loved in another's arms. And yet he loved the woman. As he pictured Charnock happy, so he pictured Kate sad, fretting out her life on that is land as he had fretted out his on the ship. And he could make her happy by a word if he broke his oath and was false to the promise he had given her. Should he do it for her sake? Would she forgive him? He would be past forgiveness when she knew.

Which was the stronger, his love for the woman or his hatred for the man? If he spoke at all, it would be for her sake, naught else. Would the man understand that, would she? Whatever happened, he had possessed her; she had been his for brief hours. Did he have the strength now to give her to someone else, even though he were dead? Being dead, would he know?

The struggle racked and tore him in his heart. He could come to no decision, at least not then. What he would do later would depend upon circumstances. One thing he could do, and that was to go and find the man. Attending to such matters as were most pressing and taking the precaution to make his will, a strange will, at which his attorney ventured to remonstrate unavailingly, at last he started on that journey across the continent in his private car. He had left the car at Suffolk, Virginia, and with a motor which had been transported with him he ran up the west side of the inlet until he came to the manor house which a local guide, picked up by the way, pointed out to him.

It was that same late spring morning when John Charnock sat on the porch overlooking the pale waters of Hampton Roads past Newport News and Old Point Comfort and the blue waters of the Ches apeake and the bluer ocean beyond. The motor car was stopped outside the great gate at the end of the long avenue of trees which led to the river road. It could have been driven in, but as he approached the house more nearly, with his mind still in a state of indecision, in order further to collect his thoughts and because he was tired from the long ride and be cause he would not trespass on Charnock more than was absolutely necessary, Langford decided to walk. Chapter XXIV

Now the sight of a passing automobile was not unusual, and Charnock glanced at it indifferently enough until it stopped at the gate. That was out of the common, for most of those who came to visit him in such fashion turned in the drive and stopped before the long flight of steps that led down from the porch to the terrace and from the terrace to the lower level of the lawn. He did not recognize the tall, slender figure which came slowly up the path by the side of the drive under the great arch of trees. Still, as the man drew nearer, he arose and with true Virginian hospitality, a hospitality he had easily learned since it was in his blood, he descended the steps to the terrace and would have descended farther to the roadway but that he suddenly recognized the visitor. He stopped dead still, surprised, amazed. Langford started, hesitated, threw back his head and came resolutely on. He mounted the first flight of steps and, as he did so, Charnock turned, drew back a little to make way for him, and the two men faced each other upon the terrace.

"Great God!" cried the Virginian at last, "you of all men. What are you doing here?"

His brow was dark, his hands were clenched.

"Why not I?" answered Langford coolly, a bitter smile on his lips.

"You say that to me after all that you have done?"

"Man," said the other, "didn't I do everything under heaven that man could do to undo it. She forgave me. Can't you?"

"No!" answered Charnock, moving toward him.

"Stop!" cried Langford. "Is your own record so clear? Have you nothing with which to reproach yourself? I ruined her life; yes, I grant it; but you drove her to suicide. Why have I not the right to fault you even as you seem to claim the right to fault me? We have both sinned against that woman, but at least in those final hours I did my best for her. Did you?"

Charnock hesitated. No one had ever spoken to him like that. He had said these things to himself many times, but no one else had ever assumed or presumed to do so, and had anyone but this man ventured upon such words, he would have met with short shift indeed. But there was so much justice and so much truth in what Langford said that, resentful though he was, hating the man as he did, he could not be blind to it.

"You are right," he admitted at last, but with great reluctance. "There is more guilt on my soul than yours, but no other man under heaven should have told me so."

"Nor should I have told it to any other man," returned Langford.

"But that doesn t explain why you come here."

"Why!" exclaimed the other. "I don't really know."

In that instant the tension under which he held himself gave way. He reeled slightly, put his hand to his heart. For the first time Charnock noticed how white he was, how sick and wretched he looked. Although he could not bear to touch the man, there was unconscious appeal in his weakness which the stronger man could not resist. He sprang instantly to his side. He caught him by the arm.

"What's the matter?" he asked almost roughly. "You look ill, weak, suffering."

"It is nothing," answered Langford, struggling manfully to control himself and to fight back the ever tightening pain about his heart. "My time's about up. If I could sit down somewhere . . !"

"Here," cried Charnock.

He half led, half carried the man, supporting him wth his powerful arms to a seat on the terrace, across which the shadow of the house fell in the morning.

"Thank you," said Langford. "Now," he fumbled in his pocket and pulled out a little phial with shaking fingers, "if you will be kind enough to open that and give me one of these," he gasped, "I am hardly up to it."

Quickly, deftly, Charnock took the phial, opened it, placed one of the tablets in the other's hand and waited anxiously. Above on the porch a servant appeared and him Charnock bade bring water, wine, restoratives. Presently Langford recovered himself, the powerful medicine acted, the tearing pain at his heart abated. It left him fearfully weak and broken, but his own master.

"Well," he said with cynical bitterness, "you see."

"Yes," answered Charnock gravely, " I see."

"I am going in one of those some day, and mighty soon now, and it is because of that that I came to see you. I wanted to talk to you about her."

"No man speaks to me about her."

"But you can't refuse the dying, you know. You can't go away and leave me here. You can't stop me by force. When I am weak, I am strong," he quoted almost sardonically.

"I shall not leave you," said Charnock. "You are paying for what you did. My God, I could envy you your going. Do you think life is sweet and pleasant to me with the memory of what I did rankling? "

"No, I suppose not," said Langford, "but I didn t really come so much to talk about her as to talk about you."

"I can't conceive that I am a proper subject for your conversation."

He said it firmly but not unkindly. Langford was too pitiable a spectacle for that.

"It's about your project," went on the other. "Will you tell me about it?"

"Haven't you read the papers?"

"Yes, but I want to hear from your own lips what you propose to do. I am a business man accustomed to large affairs. I want to hear with my own ears all about it."

Charnock hesitated. After all, why not? Standing before the other, he outlined all his plans. Rapidly, dramatically, concisely, he builded before the other's eyes the castle of his dreams.

"It is to be for her, a memorial to her, you see, so that her name shall be remembered and prayers and blessings called down upon her head by generations yet unborn."

"It is a practicable scheme," said Langford, "and a great one. Who has it in charge?"

"Men you know," answered Charnock, rapidly naming them.

"They can make it go if anybody can. I congratulate you upon it. It is a great idea. As usual," he laughed bitterly, "you have got ahead of me. While you have been working and living these two years, I have been idling and dying. But I can make some amends at least. You will see presently. Now, I must go."

He rose unsteadily to his feet.

"Wait!" said Charnock. "I never thought to do this. I never thought to speak to you again. But you can't go now. You are in no state to travel, even in an automobile. You must come to the house until you recover yourself, get a rest over night, let me send for a physician. I don't mean that there can be friendship between us. There is too much in the past that keeps us apart. I have never before been glad that I didn't break you when I held you in my arms upon the sand. But I don't know, if she forgave you, I can do it. Maybe by that I can earn some forgiveness myself. We were both fools, and you were knave, but you were man at last. I wasn't. Stay here. I won't disturb you."

"By heavens!" said Langford, flushing, "you are man now. No, I won't stay, but I thank you for your offer, and I will pay you for it."

Charnock put up his hand.

"I want no pay."

"Nevertheless, you shall have it," insisted the other. "I will give you a word of advice although to do it damns me!"

He paused, laid his hand upon his heart again, clenched the clothing about his breast as if he would fain tear it off. He was white once more, the sudden flush had gone, but his lips were set determinedly.

"Listen well to what I tell you," he said slowly. "I break my word to do it. I am false to my oath in what I say. Nevertheless I say it. Go back to the island!"

"What?" cried Charnock.

"Didn't you hear me?" asked the man, intense bitterness in his voice. Now that he had made the plunge, he realized more keenly than ever what it meant to him even in the very articles of death to think of Charnock and the woman. "Do I have to say it again?" he went on. "Go back to the island."

His voice rose until he almost cried the five words in Charnock's face. The Virgianian stood absolutely appalled. Langford looked at him a moment, laughed bitterly, turned, and went slowly down the steps. More than ever he hated him. In one bound Charnock was by his side.

"You have said too much or too little," he cried, laying his hand upon the other. "What do you mean? Why should I go back to the island? Is she there?"

In his agitation, he even shook the frailer, slighter, feebler form of the man who had just uttered those words.

"Unless," said Langford coolly, "you want me to die on your threshold, you would better take off your hand. The doctors told me that the least physical violence or exertion would be fatal to me."

Releasing him, Charnock spoke again.

"But won't you tell me what you mean? Great God, man, think what your words convey!"

"I will tell you nothing, nothing further. This is my last will and testament to you. Though I die here, I have nothing further to say to you than this: Go back to the island. . . . Damn you!"

He turned away again and went down the steps, leaving Charnock standing staring after him. He reeled slightly as he went, but he caught himself and marched on with as great a resolution as ever any soldier manifested in the point of danger. He had displayed weakness once in the presence of his enemy. He would not do it again. And while Charnock stared at him, he stepped out through the gate from under the trees, entered the big car and was whirled away.

Left to himself, Charnock sat down upon the bench and pressed his head in his hands, his thoughts in a wild whirl. Go back to the island? Why had he said that? Who was there? Did some fantastic spirit of revenge send him half way round the world on some fool's erand? Hatred spoke in the man's voice. He had coupled his in junction with a curse, which was a sufficient attest to the bitterness of his feelings. And yet truth spoke there, too. Go back to the island! What could it mean?

A long time he sat resolving in his mind his course, although he knew what it would be from the very moment that the words had fallen from Langford's lips. He must go back, if for no other reason than to settle the doubt, to answer the question, to satisfy the wild clamor of his soul, to kill the hope that flashed into his breast at the other's words.

His revery was interrupted by the arrival of a strange negro. Langford had stopped at a village tavern, it appeared, where he had procured writing materials. He had paid the boy liberally to bring the note to Charnock. The envelope was sealed. Beneath his name was written these words:

"As you are a gentleman and respect the request of a dead man, you will not open the envelope until you stand upon the island."Never was there such a prohibition. Never was there such a consuming desire in the man's heart to defy it and disregard it. Yet that vague, intangible thing we call honor, backed by a flimsy bit of paper and paste, held Charnock with fetters of steel. The envelope decided him. He rose to his feet, entered the house, sent for his uncle, told him the story and bade him get ready to start for San Francisco that night. Whittaker and the chaplain, summoned temporarily from the great undertaking, joined them at Washington, and the little party went rushing westward in a private car on a special train as fast as steam and steel could take them. And yet to the heart of the man their progress was so slow that every hour he became more frantic with impatience.Back in the little village inn by the roadway Langford, alone, lay dying. A strange lawyer wrote a few letters for him confirming a will made in San Francisco leaving every dollar he possessed to Charnock's great undertaking on condition that his name be not mentioned in it and that those who cared for him might regard it as the end of a great expiation. And so ministered unto by a strange clergyman, he passes out of sight, having made what amendment he could. He loved much in the end, surely in the end much would be forgiven him! Poor Langford!

How awful had been those two years upon that island! They would have been completely insupportable had it not been for the forethought and kindness of Langford. The books were not such as she would have chosen, but they were books at any rate, and she knew them by heart. Of the cloth that he had left, she had fashioned for herself such simple garments as were suitable to her situation, rejoicing that she was no longer compelled to wear the rough, coarse, chafing grass tunics of the past. The greatest blessing, however, of all that had been left to her was the writing paper, the note books, and pencils. They had given her occupation after all other things had failed her, for she had written down the story of her life. Not imagining that they would ever be seen by human eyes, she had poured her whole soul out on the pages. Every incident had been gone over. Not Rousseau himself had been franker in his "Confessions," but here was only sweetness and light. She had restricted her writing to a certain number of moments daily in order to prolong the occupation as much as possible, and she had carefully considered everything ere she put it down. Chapter XXV

She had dwelt most of all on her three years of life with the man on the island. She told of her hopes, her fears, her trials, her struggles, her ambitions. She neglected nothing. She told of her grief, her disappointment, of her further hope. She burned her longing upon the white page. It was such a revelation as would have thrilled the un responsive human race if it could have read it. She had a wonderful facility of expression, and writing thus out of her heart, deathless words came upon the smooth leaves. She loved to read it over from time to time, thinking sadly of that other book which had made so much of a stir in her world. And so the work grew and grew under her hand until upon a certain day in early summer it was finished.

She would add no more to it. There were a few blank pages left and a few stubs of pencil. These she would reserve for what might come in the future. If he came back to her, she would write it down. If she stayed there until she died, when she was old and lonely and broken, she would write down her final words again and leave them for whomsoever might chance upon the record in some future hour. But when she had completed it, she was strangely sad. It was as if another great chapter in her life had terminated, and she knew not exactly how she could take it up again and go on the unvarying round.

Twice daily she had gone to the heaven-kissing hill high in the center of the island, where she had laboriously builded another pyre for another beacon. Morning and evening with unvarying routine she had scanned the horizon, this time with an excellent glass that Langford had left her. Not once had she sighted a ship. He never came; no one ever came. Hope gradually died away in her heart. She wished now that she had not insisted that Langford should not say that she was alive. Her longing for a sight of the man she loved grew and grew until each day found the burden of life without him more terrible and unendurable than that of the day before. Would he never come? Would she live and grow old there and die there without him?

If it had not been for the books and for her task, she could not have survived. Her brain would have gone, her voice would have gone. She kept that in use by reading aloud day by day, page after page, from one or the other of the volumes that she had.

One evening she climbed wearily to the top of the hill and listlessly swept the horizon, the bare, vacant, unbroken horizon, which she had surveyed morning and evening all these years. She expected nothing, but suddenly there sprang into the object glass of the telescope a dark blur which she had never seen before. Her hand trembled so that she almost dropped the glass. She strove to pick up that object again, but could not do it in her nervous agitation. Finally she lay down upon the hill and rested her arms upon a little rise of ground, and thus steadying the glass, managed to find it once more. It could be nothing but the smoke of a ship!

The sky was without a cloud; she could not be deceived. It was miles away, of course, yet if the ship was visible to her, the island would be more visible on account of its vast bulk comparatively to those aboard of her. The ship, if it were bound on some trading voyage, would probably pass by. What should she do? She had sworn that she would stay on that island, live and die there, unless he came to fetch her, but the longing to see him, to hear about him, to know what had become of him, had grown so great that her resolution was trembling in the balance, and in the smoke of that passing ship it vanished into thin air.

She had means of striking a light which Langford had left her, which methodically and mechanically she always brought with her when she climbed up the crest of the hill to seek for a sail. She lifted the matches and approached the beacon. She remembered how once before she had lighted that beacon; she remembered how he had pleaded with her not to do so, how in doing it she had brought the world upon her with such terrible consequences to her. Should she do it again? What would happen if she did? She laid the matches down and lifted the glass once more. Yes, the ship was still there! She was so far away indeed that the short time which had elapsed would have made no change in her apparent position.

She looked back to the westward. The sun was setting. There would be no twilight. Darkness would come swiftly. If she did not light that beacon, the ship would pass in the night. If she did light it, the darkness would lend force and efficiency to it. No ship would disregard such a light in such a quarter. Should she do it?

In one swift moment her resolution was taken. She dropped the glass, turned to the box of matches which she had hoarded for this very purpose, knelt down, struck one of them, watched the blue flame develop and swell out in the still air, paused for a moment hesitant, touched the light to the inflammable mass of dead wood at the base of the pile. In one instant the flames were roaring amid the larger timbers, as they had roared on that morning nearly two years ago. For one instant she would have torn down the pyre and scattered the flame, but it was not within her power. Nothing could stop that raging blaze now.

As the flames crackled up through the wood, leap ing and catching, the sun sank and the darkness fell. Her last act ere the curtain of night shut her in had been to fix her glass upon the faint blur of smoke. Now she could see nothing. It was a moonless night, but bright with stars. She moved away from the fire and sat down as she had sat before, sheltered by the peak, to watch the sea. Now that she had done what she had sworn not to do, she was eager for the success of her attempt. Indeed, she thought that if yon ship did not see that fire and did not come to the island and take her off, this time she would really die; she could not stand another disappointment.

And so she waited, wondering, through long hours while the flames exhausted themselves and by and by fell to a heap of glowing ashes. Suddenly there leaped out through the darkness a distant twinkle of light. It was too low for a star. Feeling for the telescope, she found it and with difficulty focussed it on the tiny spark. It was a red light, the light of a ship! The vessel had seen the signal. It was nearer, much nearer now. She knew about how far such a light could be seen. The ship was coming toward her. She almost fainted from the revulsion of feeling from hope to certainty, from anxiety to assurance.

As she watched it, she suddenly saw a dash of sparks from the smoke stack. Fixing her eyes on the light again, she thought she caught a glimpse of a white blur. For a moment her heart sank at the thought that it might be Langford's yacht, and yet even his vessel would be welcome, any boat, indeed. The light grew larger. The night was very still, the sea entirely calm; sound carried a great way under such circumstances. Presently she heard the throb and beat of a screw. The vessel was coming nearer. There was some faint light from the many stars above her head. She thought she could make out the bulk of the ship.

It was close at hand now. She must go down to the beach to meet it. She rose to her feet and started down the hill. She went slowly, cautiously at first, but finally she broke into a reckless run. She strayed from the path in her excitement, her foot caught in a projecting root. A sharp, excruciating pain shot through her. Something seemed to break in her ankle. She pitched forward on her face and lay still.

When she came to her senses light was shining in her eyes. Men stood about her holding ships lanterns. Someone bent over her as someone had bent over her five years before when she lay sense less on the sand. A voice she knew called to her; arms to whose touch she thrilled gathered her up; she felt a heart beat against her own. He had come back. He was there.

"Woman," said the man, "I have come back to you."

"Man," returned the woman, oblivious of those who stood around, holding the lights, to whom she gave no single thought indeed they were those who knew her well "Man," she asked, true to her resolution, "do you love me as much as on that night?"

"More, a thousand times!"

"And do you think me worthy . . .?"

"Do not ask! It is I who am unworthy of you."

"I can die now," said the woman softly, lapsing into unconsciousness again.

"Great God!" cried the man, straining her to his breast again, "have I found her only to lose her."

"Let me look," said the surgeon whom by good chance they had picked up at San Francisco. "She didn't look like a dying woman a moment since. Lay her down, man, and stand back."

Whittaker and the chaplain pulled Charnock aside. The surgeon took his place by the prostrate figure.

"Lights here!" he cried. He made such rapid examination as he could, seeing in a moment one foot lying inert, out of place, and helpless. " She's only fainted," he said. "It's her ankle. She's broken it in the darkness coming to meet us. We will take her to the ship."

"No," said the man, "she must come of her own free will. Send to the ship for bandages and what ever you require."

"Very well," said the surgeon, rising and conferring hastily with Mr. Whittaker. "Meanwhile, your handkerchiefs, gentlemen, and some cold water."

"There is a spring hereabouts," said the man, "on the other side of the hill."

"I will fetch the water," said the chaplain.

He was wearing a tightly woven straw hat in which he could easily carry it.

Mr. Whittaker turned and ran to the beach, whence he sent the boat off to the ship. The surgeon meanwhile had bound up the woman's ankle, had bathed it with water and whiskey, and had forced some of the spirit down the woman's throat, but the man's touch, his presence, would have sufficed to call her back to life.

"Do you suffer?" he asked tenderly as consciousness returned to her.

"Not since you are here," she said. "I ran to meet the ship and fell and hurt my ankle."

The doctor has fixed it up for you. We have sent to the ship for bandages."

"Man," she said, "whose ship is it?"

"Mine."

"Did you see my signal?"

Yes, we were glad because it told us that you were alive, but we were coming directly here."

"And did you come for me?"

"For you only."

"How did you know that I was here?"

"I didn't know it."

"Why did you come, then?"

"I was sent here."

"Who sent you?"

"Langford."

"Did he tell you I was here?"

"No, he told me to go back to the island, that was all."

"Nothing more?"

"He gave me a letter which I was to open when I set foot upon it."

"Open it now," said the woman.

She had risen to a sitting position. He knelt be side her, his arm around her supporting her. He carried the letter in his pocket. He had slipped it there as he started for the shore. He took it out and handed it to her.

"You may open it," he said.

With trembling fingers she tore the envelope. Inside there was nothing for him, but a smaller envelope addressed to her. The chaplain held the light close to enable them to see.

"It is for me," she said, "not for you."

"Yes," said Charnock gravely, stifling a spasm of jealousy in his heart.

She laid it in his hand.

"You may open it."

"Not I," returned the man, touched by this confidence. "It is for you."

Without more ado she tore open the second envelope. A little slip of paper fell from it. His message was astonishingly brief. While Charnock resolutely averted his head, she read these words:

"I broke my word once to your sorrow; I break it again to your joy. Won't you try to remember, now that I am gone, that I tried to make amends and that I gave him back to you."She stared at the paper a moment, and then she read the simple words aloud.Charnock understood vaguely that in some way Langford had known that the woman was alive -- how he could ascertain later -- and that she had made him promise not to tell; that he had broken his promise, and died.

"Now that I am gone! I don't understand the words," said the woman.

"They are his last words, I take it," answered the man. "He looked like a dead man when he came to me at my house in Virginia and told me to go back to the island."

"Poor Langford!" said the woman.

"May God have mercy on him!" added the old chaplain solemnly. He knew the story, too. "Do you forgive him, my child?" asked the old man as he, too, turned away to leave these two alone.

"With all my heart," answered the woman.

"And do you forgive me?" asked Charnock softly.

"With all my heart!" again answered the woman, but with a change in the intonation that made all the difference in the world between the two statements.

She turned her face toward him. She reached her arms up to his neck as he bent over her. She forgot everything in the long kiss he pressed upon her trembling lips while he held her close to his heart, in that still and starry night, on that gem-like island of regeneration, in that far Pacific sea.

THE END

|

|

|

|

BACK

TO COVER PAGE

BACK

TO INDEX

Comments/report typos to

Georges

Dodds

and

William Hillman

![]()

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL &

SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

other Original Work ©1996-2007 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.