Volume 1826

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/gozlan.htm

| Author's Preface. | |

| Translator's Preface. | |

| Chapter I. | I Deal in Wild Animals. |

| Chapter II. | How Wild Animals Dealt with Me |

| Chapter III. | I Go in Search of a New Stock-in-trade |

| Chapter IV. | The Unknown Island |

| Chapter V. | Frightful Companionship |

| Chapter VI. | A Mysterious Interposition |

| Chapter VII. | I Explore My Island |

| Chapter VIII. | Saved --- or Lost? |

| Chapter IX. | Astonishment Follows on Astonishment |

| Chapter X. | Monkey Justice |

| Chapter XI. | Again that Mysterious Fire |

| Chapter XII. | In the Enemy's Hands Once More |

| Chapter XIII. | Fresh Torments |

| Chapter XIV. | A Monkey Orgie |

| Chapter XV. | Discoveries |

| Chapter XVI. | The Mystery of the Skeleton Explained |

| Chapter XVII. | A Hundred Thousand Bottles of Champagne for a Glass of Water. |

| Chapter XVIII. | I Find Myself a Monkey-King |

| Chapter XIX. | My Policy and Reign |

| Chapter XX. | Disaster |

| Chapter XXI. | Deliverance |

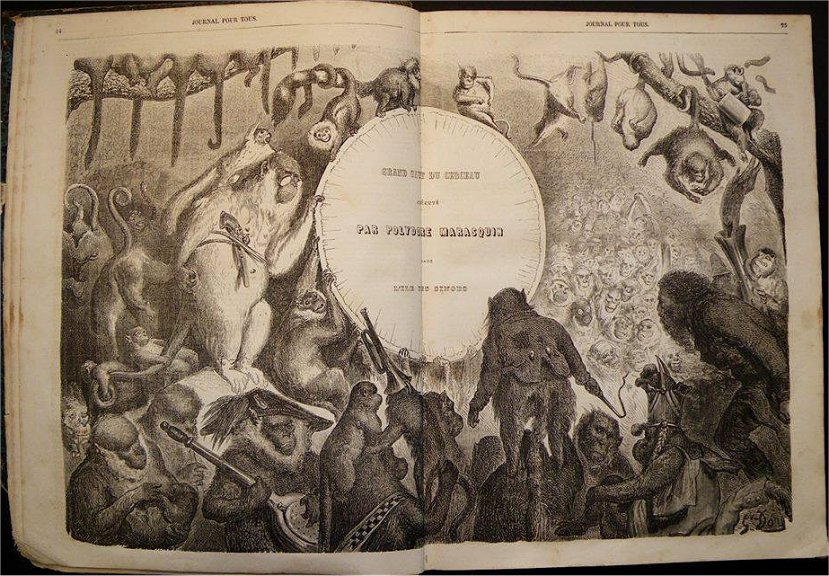

Monkey Island

Last year, an author of noble intelligence, enhanced by an exemplary generosity, endowed, under the rather transparent veil of the Société des gens de lettres, several prizes destined to reward, amongst other creations of the mind, the best tale that would be sent in to a special contest. Having had the honour of being one of the judges in the field, we were in a position, in our modest stall, to count the number of lances, as it was said of yore in the language of chivalry, presented at this magnificent tournament. There were countless lances. If a few returned with the gold pennon on their lance, many were those nobly broken in the fray. Amongst the innumerable short stories addressed to the Société, and subjected to the contest criteria, there are some that will leave, in the annals of the committee, a lasting memory of corners marked with an odd symbol. Personally, we have read many whose characters were drawn with inks of different colours, and that, no doubt, with some sort of cabalistic purpose which we were unable to penetrate. We beheld others framed by ornamental borders, executed with the patience and monastic perfection of master copyists of the Middle Ages. The grammatical error was encircled with lovely little cherubs begging forgiveness for the compromised syntax. Nor would we want to omit a short story, otherwise most worthy, written at the foot of the Malakoff tower, beneath the crumbling walls of Sevastopol: it still smelt of powder. The northern climes also sent its own literary dispatches: two tales sent to the contest, dated, one from the confines of Sweden, the other from the more northern borders of Norway. Even the Lapps answered the call, from the city of Treviso. Author's Preface

By way of Spitzbergen, we will cross the Kamchatka and Japan, to arrive directly in China, which has not forgotten us. The supremely fanciful land of blue could not fail to have itself represented at the gathering of tales. Macao is the Chinese city from which was sent, to the headquarters of the Société des gens de lettres, through seas and tempests, in a lacquer chest, a tale which fate wished us to judge; but judge in first instance only.

After having read this tale, we were preparing ourselves to draft our faithful report, but we recognized with dread that the tale contained three or four-fold over the number of lines strictly allowed according to the wishes of the endower, and given the need of not having to evaluate the worthiness of twenty in-folio volumes, when one had only reasonably asked to crown common sense, wittiness, gracefulness, imagination --- the flower, the aroma of a few pages. Thus our task as reporter became pointless. The Chinese tale had put itself outside the terms of the contest.

Most saddened for our admirable colleague from Macao, we were already rolling up his ill-fated manuscript : we paused abruptly in this melancholy rotary motion that all rejected authors know. A thought had stuck us. We asked ourselves why, for want of the glory and dangers of a contest, our Chinese colleague could not have the more peaceful pleasure of some good publicity in a magazine. Let us give him this pleasure which he deserves. As with everything that comes back from the brink, his story appeared to us to be interesting in its point of view. They are memoirs. And notwithstanding what Pascal may have said against the "MYSELF," --- Pascal who never spoke but of HIMSELF, --- the "MYSELF" will always be read and preferred. These memoirs, as verily they are memoirs under a fancy moniker, are not exactly written in Chinese, though they were gathered on rice paper.

The author tells us, in a note tucked away in a corner of his manuscript, that he is begotten of Portuguese parents, that he is born of a French mother, and that he completed some advanced studies in the home of the brothers of the Congregation of the Mission (Lazarists), established in Macao. Again, this admission contravenes the practices of academic contests. So what? our most deserving colleague, Mr. Polydore Marasquin, does live in China; one must pardon him many things. Is he not already sufficiently punished for having written too long a work? It is to him, rather, that we beg forgiveness for having published his book without his approval, having cleaned up some of his sentences, and finally of having signed the whole thing with our name, which is of a physiognomy even more Chinese than his.

--- Léon Gozlan

The author of "Les Emotions de Polydore Marasquin" enjoyed a brilliant reputation at a period which will always be regarded as specially important in the literary history of France --- that is to say, during the quarter of a century immediately following upon the revolution of 1830; and even now, when the characteristics of popular French fiction have undergone a greatly to be regretted change, his works are read with pleasure by all of his countrymen whose tastes have withstood the pernicious influences of the generation of writers who have done, or are still doing, their worst to poison the springs of romantic literature. Translator's Preface

Léon Gozlan was born at Marseilles in 1806, and, being unfavoured by fortune at his birth, was destined by his parents to earn his living as an assistant-teacher in one of the schools of his birthplace. But speedily growing weary of the dull monotony and routine of this kind of existence, he one day wrote to the head of the establishment in which he was engaged:

"SIR,& -- Denis the younger, a tyrant out of work, set up a school at Corinth, and I thoroughly well understand the drift of this fancy of his: being no longer able to torment men, Denis took to tormenting infants. It was a compensation.

"As to myself, who have not yet any need for making little children responsible for the harm I have done to grown-up people, I confess, with all humility, that the profession of schoolmaster is decidedly disagreeable to me.

"When you receive this letter I shall be on board a ship on its way to the Senegal. Should I ever become King of the Mandingos, the most amiable tribe of negroes known on the face of the earth, be assured that I shall hasten to inform you of that happy event."

He was not more than twenty years of age when he adventured upon this voyage to Africa. What his purpose was in undertaking it, if he had any precise purpose, is unknown, for as to his having had any serious idea of getting himself made King of the Mandingos, it is hardly credible. Indeed, a rumour went abroad to the effect that, so far from seeking to establish good relations between himself and those excellent inhabitants of Senegambia, he would, on the contrary, have been more likely to deal with them as negroes were commonly dealt with at that time. Whatever were his actual relations with the Mandingos, however, the only fact certainly known was that, after exploring two of the principal affluents of the river Senegal, he took ship back to France, apparently enriched only by the discovery that the charms of life in Paris were incomparably more to his taste than those of African travel.

Deeply imbued with the belief that "to dare is to succeed," he, directly after his return, threw himself heart and soul into the career of literature, and gave to the public a long series of works of fiction, as well as plays, which won for him a recognized place in the ranks of his most brilliant contemporaries --- somewhere between Balzac, from whom he borrowed part of his keen observation, and Frédéric Soulié, to whose literary example he was indebted for some portion at least of the passionate sentiment he displayed in some of his romances.

But of his works in general this is not the place for speaking at length, and of the present book I need only say that, strikingly original in conception, it is executed with an untiring vivacity of idea and expression, making it not only one of the best and most characteristic of his lighter fictions, but enjoyable alike by young and old readers.

I was born at Macao, in China, and am descended from one of those bold adventurers who, towards the end of the fifteenth century, audaciously set sail from Lisbon, under the command of the renowned Vasco di Gama, to go and conquer the Indies. But however I may be entitled to pride myself, so far, upon the certainty of my genealogy, I must, in candour, admit that I have no plausible reason for believing myself to be the issue of any of the high-born followers of that illustrious chief. Chapter I

My grandfather has, indeed, sometimes insisted that our name of Marasquin comes by corruption from Mascarenhas one of the greatest names among the Portuguese who accompanied Vasco di Gama from the banks of the Tagus to the extremity of Asia; but I have always entertained serious doubts as to my grandfather's accuracy on this point. He himself, so far as I ever knew, was nothing but a hardworking tradesman established at Macao. His eldest son --- my father, Juan Perez Marasquin --- was never anything else, and I owe it to his memory to say that, during his life, his ambition was limited to being accounted an honest man and fair-dealing bird-fancier; for that --- I do not blush to own it --- was my father's calling, though there have been persons who have insinuated that he was nothing more than a simple poulterer. Of this the disproof is easy. Not only did my father deal in live birds, but he kept a menagerie --- one of the most extensive and variously supplied in the Portuguese Indies --- in which he collected all kinds of rare and curious animals. Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and New Guinea were represented in it by specimens of the most remarkable and uncommon creatures to be found in the all but impenetrable forests of those places. In the round of commerce there is hardly one that is more lucrative, owing to the taste of the Europeans established in the Indies and the almost insane passion of the Chinese for these interesting examples of natural history. To the sale of living animals my father joined the profession of taxidermist, and the latter was not the less profitable part of his business. From him I received lessons in the learned and delicate art of restoring to defunct birds and beasts the forms and habits exhibited by them during life. Thanks to his able instruction and example, I ultimately acquired remarkable skill in taxidermy; and it will be seen, in the course of this veracious narrative, that, to my aptitude in this useful and beautiful science, I owe my escape from a tragic end. For more than a century our business had prospered at Macao. On coming into possession of it by right of inheritance, my father had increased its field of operations; and, with the aid of the good and economical woman he married, he succeeded in making it the best establishment of its kind in existence. But if this sort of business brings in large profits, as I have said, it is, on the other hand, difficult, perilous, and often ruinous, as I myself have only too surely proved. Few people are aware of the difficulties under which the trade is carried on; it involves much more than merely the question of buying in the cheapest and selling in the dearest market: the animals have to be procured alive, before they can be profitably sold; hence the necessity of being at once tradesman and hunter, or, rather, of being a hunter before being a tradesman. My father, therefore, hunted and captured the animals he traded in --- a trade which I, in turn, learned by accompanying him, sometimes to the Chinese coast, sometimes into the jungles of the island of Hai-nan, so rich in wild beasts, sometimes even to Japan, in spite of the dangers inseparable from a navigation carried on in ill-constructed vessels; in spite of the Malay pirates, veritable seacormorants, devouring everything they come across; and in defiance of the dreadful penalties which, at that time, awaited all foreigners whom the Chinese and Japanese caught upon their inviolable territories. From these distant and perilous expeditions my father, and afterwards myself, brought back panthers, tigers, leopards, boa-constrictors, but, more especially, innumerable species of monkeys. It was in one of our last hunts on the shores of the island of Formosa that my father, attacked by a tiger, which he was about to envelop in a net, received several desperate injuries from the claws of the enraged beast. I was fortunately able to snatch him from the furious brute; but though I had the happiness to bear him back to his home, I had not the happiness to save his life. Under care of the unskilful doctors of the country, he languished for two years, his wounds refusing to heal, and died at length in horrible suffering. In giving up his last breath in my arms, he made me promise not to continue his perilous calling. I promised I would obey his dying wish; but as he had not left me wherewithal to support myself and my mother, and as I, --- to speak frankly --- had no taste for any other profession, I regret to be obliged to confess that I did not redeem my promise. The account I am about to give of the adventures I was destined to undergo will tell whether I had cause to applaud or to regret the course I took. On entering into possession of my father's business, I set to work with redoubled activity, with a view to proving to my wealthy patrons how worthy I was of a continuance of their patronage. I increased the number of my rarer animals; I sent out travellers, instructed to obtain specimens of other beasts of species wholly unknown, or little known, in the latitude of the Indies. Taught by experience, that the appearance of luxury dazzles, and consequently attracts the attention of buyers, I thoroughly renovated the exterior and interior of my bazaar. Bronze and gilding relieved the hitherto naked aspect of my cages. The utmost neatness reigned throughout my establishment, which I caused to be lit with gas --- a surprising novelty in Macao. Here I must indicate a particular trait of my character. At the time I took to the profession of bird-selling, I had a great love for animals, owing, in the first place, to my benevolent organization, and, subsequently, as a natural result of the studies I had been called to make, as to their forms, their expressions, their movements, their habits, their manners, their instincts, their passions, their intelligence, their sympathies, their antipathies, their caprices, their maladies, their affinities, more or less marked, with mankind, and the thousand other attributes essentially proper to their nature, which is, perhaps, still more obscure and mysterious than our own. I had even pushed my observations on the beings we have for cage-neighbours in the menagerie of the world so far, that I could easily recognize those whose instinctive aptitudes correspond with ours --- which would have made them, for example, lawyers, if there were any amongst monkeys; these were continually gesticulating, haranguing, and apostrophizing. I recognized others who would have made doctors --- these constantly employed themselves with the physical condition of others, looking at their tongues, examining their throats, and prying into the depths of their eyes: others would have made actors --- these grimaced, gambolled, and danced from morning to night: others, again, would have made astronomers --- these invariably bore themselves in such a way that the sun rose in a line with their noses: with the same infallibility of appreciation, I recognized those who would have had a taste for commerce --- these carefully gathered up all the fruit and grain that fell from the negligent hands of their companions, and heaped them in a corner. In the same way I could recognize misers, spendthrifts, swaggerers, worthy fathers of families, good or coquettish mothers, and bad sons; but, particularly, I could distinguish all shades of thieves, from the blacklog of fashionable society to the highway assassin. I could have said, with unerring precision, "There is a monkey who, if he wore a white cravat, might ride in his carriage; and there is another who, if he only habitually dressed himself in a black coat, would assuredly be hung." I thus attached myself to my boarders in the character of a naturalist, painter, physician, and philosopher, even more than by my title of buyer and seller; by force of penetration, I should have succeeded in being able to read in their eyes whatever were their thoughts, their wants, and their desires; I have no doubt whatever that, in this psychological study, I should have attained a power unknown to all the naturalists in the museums of Europe, if the fatal accident through which I lost my father had not suddenly checked my fondness for animals; for, after that event, I found it impossible not to look upon each one of them as the accomplice of the tiger which had killed him. This antipathy grew from day to day, and caused me, at first, to neglect them, but afterwards to punish them severely. They quickly understood the change which had been wrought in me; for animals keenly, and even more readily than ourselves perhaps, realize the difference between good and ill treatment; and they paid back, in hatred and spite, the punishment which I, sometimes a little too inconsiderately, inflicted upon them. It was a continuous struggle between them and me, reaching, at length, a post at which I could no longer control them, save with a rod of iron. From this state of things it resulted, that I ceased to be able to make them leave their dens, for the purpose either of punishing or taming them; and, on my side, I could not prudently venture into the cage of any one of them, On both sides, it was a condition of permanent anger and hostility; and there was no kind of ill-turn which they did not play me, the last one being of a nature so cruel and terrible that, if I passed it by in silence, the cause of the prodigious emotions it was afterwards my fate to endure would scarcely be intelligible. One brute alone in my collection was guilty in the highest degree, but all contributed to the terrible result, by their universal animosity towards me. I will, in the next chapter, relate the frightful vengeance of which those redoubtable creatures made me the defenceless victim.Vice-Admiral Campbell, who, at that period commanded the English naval force at Oceania, was accustomed, every time he came to Macao, to pay a visit to my bazaar, and to purchase a few specimens for his aviary and menagerie, in which he sought to beguile the tedium of his voyages between the islands, and the inactivity to which he was often condemned for months together, while his ship was lying at anchor. Chapter II

I think it useful to say a few words here as to the importance of the British naval stations in the waters of China and Australia.

The object for which they are established, but which they do not always accomplish, is to protect the lives and commerce of Europeans, in the latitudes infested by Chinese and Malay pirates --- yellow-skinned, innumerable, terrible.

These dreaded serpents of the sea, who are to Oceania what the Algerines once were to the basin of the Mediterranean, knew no authority under the sky; neither that of the Emperor of China, backed by his mandarins, nor that of the Sultans scattered about the great islands --- as in Borneo and Mindaneo; nor did they any more regard the authority of the British or Dutch officials, representing their respective nations --- nations powerful enough, no doubt, but too far off to command respect from such lawless hordes.

The Malay pirates dare all, and seek their prey everywhere. The Sooloo Archipelago, which numbers one hundred and sixty isles, is entirely peopled by them. On a given day they set afloat five hundred junks, manned by no less than five thousand sailors. They scour every hole and corner. The plunder they seize they share amongst them; their prisoners, if they take any, are held to ransom, but are more generally killed. At times they have pushed their audacity to the extent of swooping even into the midst of great commercial centres, such as Sumatra and Java; and, on one occasion, they came for powder and ball to Macao, which was compelled to supply them. As a race, they are indestructible; they have endured for ages, and they will endure for ages longer.

It is to protect British subjects, especially, against the poisoned cresses of these ferocious sea-robbers, as I have before said, that the British Government constantly station ships on the thousand points of the interminable coasts of China.

These British ships are often obliged to remain for entire years, in protection of places threatened with a visit from these pirates; in such cases, the officers establish themselves on shore, set up tents, or even establish groups of houses, in which they live with their families.

Naval campaigns of this sort are greatly dreaded by English sailors, compelled to fight at once against tempests, Malay pirates, fevers of all colours, and, worst of all, against the depressing influence of weariness --- that yellow-fever of the soul!

Vice-Admiral Campbell, who, as I have already said, commanded on one of these stations, had hoisted his flag on board the fine frigate Halcyon.

He was preparing to quit his anchorage at Macao the day when, in company with his principal officers, he paid a visit to my menagerie. Besides my aviaries, which were well stocked with birds of all climates, I possessed a rich collection of quadrupeds --- gazelles from Egypt, bisons from the prairies of Missouri, several blue goats, fourteen or fifteen great ant-eaters, jaguars, Senegal leopards, otters, polar bears, black panthers, antelopes, reindeer, one-horned rhinoceroses, Brazilian llamas, lions, and a magnificent show of tigers.

But the most special feature of my display was my gathering of monkeys, representing all phases of monkey character --- the gay, the malicious, the cunning, the savage, the grave, the pensive, the threatening, the witty, the stupid, the melancholy, the grotesque. I had them of all species, of all sizes, from the tiny marmoset to the enormous mandril and baboon.

Among all these monkeys, four especially disputed the curiosity of the crowds of persons who visited this gallery, firstly, two baboons of unequalled strength and ferocity. Both were bulky as men, intelligent as men, and, I was going to add, both were as malicious as men. They shook their cage so as nearly to tear it to pieces; often they overturned it, and, in the height of their rage, wrung the iron bars of which it was made as if they bad been rods of wax. What made the sight of these ferocious beasts so peculiarly attractive to the onlookers? Was it the extraordinary cruelty of their demeanour? I am almost tempted to believe so.

Two other monkeys shared the sympathy of the visitors, a male and female chimpanzee, about the same in age and equal in grace. The male was gentle as a young girl, delicate, sensitive, understanding everything, going as near to the limits of intelligence as is given to a being deprived of the divine light of the soul. He was fond of children, played with them, and exhibited such a passionate liking for music as to forget to eat when he heard the sound of an instrument.

He performed about me the office of a well-instructed footman, changing the plates at dinner and serving the wine --- even eating at table with me when I invited him. The attentions I paid him excited the other monkeys I almost to a frenzy of jealousy; and often their hatred left traces upon his soft and silky coat.

As to the fourth monkey, contrary to the habits of most of her sex and species, the young chimpanzee, instead of longing for ribbons, laces, and embroidered handkerchiefs, was content with her own natural grace and gentleness. She was never so happy as, when some one gave her a flower, which she would place upon one of her ears, or gaze at by the hour together in an attitude of melancholy. The soul of Mignon seemed to have passed into the frame of this pretty creature, and to speak tenderly from her yellow-blue eyes.

I had called my baboons, the one Karabouffi the First, the other, Karabouffi the Second; and I had named the male chimpanzee Mococo, the female Saïmira.

Mococo was deeply in love with Saïmira, and Saïmira was scarcely less deeply in love with the charming Mococo: it was, on both sides, a first love, simple and frank, interesting to follow as a study of the heart and emotion and thought among beings temporarily placed between the man and the monkey --- strange beings, whom an effort of genius may, one day perhaps, range in the class of men, from whom they are separated only by a transparent veil. A flash of lightning may break through this barrier and humanity count one family more.

Karabouffi the First also entertained a dark and terrible love for Saïmira. Nothing can compare with the black jealousy of the baboon. When he saw the two pretty chimpanzees pass in front of his cage, enjoying the liberty of going about the bazaar, his iron nails were drawn up like hooks, his savage eyes flashed maledictions, his blue lips were compressed like those of a vice, and his grinding teeth seemed as if they were burying themselves in one another. Terror spread throughout the menagerie.

There was not one of these animals, however, which did not remind me, point for point, of all the characters, all the desires, all the passions of mankind, on an infinite scale. I remained convinced with Buffon, who has written so admirably concerning animals, that if, instead of beating them, maltreating them, and making them constantly suffer, we were to study them with sustained interest, we should penetrate into the midst of an immense and unexplored world of ideas and sensations, wherein we have not yet so much as set foot.

Vice-Admiral Campbell was so pleased with the antics, the docility, the strangeness --- and, it must be confessed, also with the ferocity --- of my collection, that, before leaving, he purchased a pair of monkeys, his example being deferentially followed by the whole of the officers of his suite.

I own that I did not at all like to separate myself from Mococo and Salimira, but the Vice-Admiral's wife took so strong a liking for them, and pressed me so much that, in the end, I was forced to let her have them. I was satisfied, moreover, that my lady would take as much care of them as myself, and was careful to impress upon her the necessity of always keeping them out of the reach of their persecutor, Karabouffi the First. This she promised me to remember, and I confidently abandoned to her charge my two poor chimpanzees, who appeared to be still more affected than myself at the separation. They embraced me like two children, and their tears trickled down upon my hands. I was so moved as to be upon the point of taking them back, but I was a trader, it was my business to sell whenever I could; interest weighed down the scale.

As nearly all these gentlemen on the naval station, as well as their ladies, purchased my monkeys in pairs, as will have been remarked, it followed that, not possessing a complete number of families, one of my two baboons, Karabouffi the Second, in default of a mate, was left upon my hands. This situation irritated him to such a degree that he roared with rage and fury when he saw the rest of his cage companions go away.

Those, in their turn, taking pity on their comrade left in captivity, uttered the most savage cries, and tried hard to avoid being carried on board ship; it was, indeed, only by the free use of the lash and other means of coercion that they could be embarked by their new owners.

Nothing can convey a just idea, no description, no painting, of the dark and threatening look darted at me by the solitary baboon when I reached the bazaar after the departure of his companions.

The vengeance of the man most deeply moved by hatred, most fiercely irritated, never condensed in his eyes so many threats as I read in those of that baboon. I saw in them blood --- my blood.

This sale of monkeys, on which I had realized enormous profit, had taken place more than a year, when one night I was awakened by a horrible feeling of suffocation, by a dense smoke, which seemed to rise from between the joints of my bedroom floor. This floor, made of very thin boards, was immediately over the menagerie. I was stifling; It was with great difficulty that I was able to rise and make my way to the window. I throw it wide open, to save myself from being killed by asphyxiation, and because my mother was lying in an adjoining room.

But the air no sooner entered the chamber than, not smoke only, but flames, ascended from the openings in the floor --- flames enveloping the entire building from basement to roof!

My first thought was to rush for my mother. Too late! The back room, which she had made her bed-chamber, had been the first to be invaded by the smoke, and the smoke had killed my poor mother in her sleep, before she could call for help. Those who came to offer assistance had to tear me from her room, where I wished to die by her side.

I was carried away out of the burning house by neighbours, who laid me on a stone bench, whence I gazed upon the destruction of my establishment. Through the gaping entrance to the fast vanishing bazaar I was witness of a spectacle which I shall never forget.

In the midst of the flames which were roasting my beautiful birds, in the embraces, of which my magnificent tigers were writhing in horrible torments and uttering the wildest cries --- none daring to attempt to extricate them --- the baboon was dancing, chattering, romping, with hideous delight, waving a flaming brand in either hand. His attitude, his cynical looks, everything in the expression of his features, told me that he was the author of the conflagration; that, in this night of long-meditated vengeance, he had contrived to get possession of some lucifer matches, with which he had seen the bazaar-keeper light the gas; that he had succeeded in breaking his chain as well as the bars of his cage, and then turned on the gas to the full and set fire to it. That was the supreme and terrible vengeance of Karabouffi the Second.(1)

Somebody killed him with a gunshot in the midst of the flames. But I was, none the less, ruined, and had, none the less, lost my excellent mother.

Under the weight of so many afflictions and sufferings, I resolved to abandon my profession, my business as a bird-fancier, remembering, somewhat late, the advice of my father. For two years I traded in ivory, feathers, and furs; but not being versed in this kind of negotiation, I obtained but very small profit, and saw no hope of doing much better for the future. Chapter III

Then, too, this kind of life, so. much less active than that which I had formerly led, did not please me; whereas my previous mode of living was constantly brought back to my mind, by the force of habit and the bent of my studies in natural history. Even the dangers which it entailed made me regret it. In short, after many hesitations, I determined to return to it.

I was still young, and there remained to me one thousand piastres, placed at interest in the house of Señor Silvao, of Goa. I was thus in a position to reconstruct and stock my establishment; but, to do this, it would be necessary for me to make two or three voyages to Oceania, where the best hunters of wild beasts and birds of prey are to be found; and I further calculated upon hunting with them myself through the woods and marshes. It was a bold and adventurous resolution; but I had no other means of re-establishing myself at Macao.

Very shortly after making up my mind to this effect, I took leave of my relations and numerous friends, and made the final preparations for my departure.

I freighted a Chinese junk on my own account, to be at my sole disposal for an entire year. My first point of destination was New Holland --- that immense island, almost as large as a continent --- where I was sure, according to the accounts of travellers, to meet with the most powerful, the most varied, and the least known animals in creation.

I set sail in my Chinese junk on July 3, 1850, full of confidence in Heaven. The vessel I had hired did not make up for her slowness by strength of structure. It was an old junk, worn out by numberless voyages to the Corea and Japan, which might once possibly have been able to resist rough weather, but against which it now offered but a slight promise of resistance.

My first object being to reach New Holland, or Australia, we steered due south on quitting Macao.

During the space of a week we were favoured with a wind which carried us in that direction. We speedily, therefore, found ourselves in the midst of the Philippines, in spite of the small amount of order which reigned amongst the crew, composed of eight Chinese, eight Malays, and eight Portuguese --- three nations holding each other in the utmost detestation, somewhat as the Corsicans and Genoese did long ago, and, like them, finishing all their disputes by the arbitrament of the knife.

During the passage of the Island of Mindanao, and at the moment of entering the Strait of Macassar, the junk sprang a leak, and, as if to make us pay for the fair weather we had so far enjoyed, the sky grew dark and charged with storm from pole to pole.

For ten days we struggled to cross the Strait of Mindanao, the wind and currents constantly forcing us to the west; and the more we strove to resist this deviation from our proper course, the wider grew the openings in the sides of the junk.

To aggravate our position in the midst of a sea already perilous enough, the crew refused to work at the pumps, and so the water increased in the hold from hour to hour. One by one the Chinese, the Malays, and the Portuguese retired from the labour, as being too severe. Severe the labour was, it is true; but upon it rested the safety of all on board of the vessel.

Captain Ming-Ming, I then but too clearly saw, had no control over that antipathetic assemblage of sailors. I suspect even that, at an earlier date, he had been engaged in piracy with the eight Malays, who treated him on a footing of equality, clearly indicating an equivocal confraternity in the past, and destroying all present authority over them.

This discovery was very little assuring to me, who for a long time had been thoroughly acquainted with the conduct and humanity of these terrible miscreants. The revelation greatly alarmed me, I do not hesitate to confess; but I concealed my terror. Nevertheless, I loaded a pair of pistols, and put one in each of my trousers' pockets.

The crew had entirely ceased to work the pumps, and the water steadily rose in the hold. Less good sailors than either the Chinese or the Malays, the Portuguese were at length terrified by the fate with which we were all threatened. They talked of altering the vessel's course, but they were opposed and their purpose defeated by the Chinese and Malays; and this served to confirm me in the idea that I was not mistaken in regarding them as old pirates, seeing how strongly disinclined they were to show themselves in any port under the control of a regular police.

Besides, whither were we to steer? Where were we? On which side of the equator? Were we running towards the Straits of Malacca or those of Macassar?

It was not Captain Ming-Ming, much abler at smoking opium than in navigating a ship, who could answer these questions. The sky was black, the wind tore our big bamboo sails to shreds, and we were settling deeper and deeper in the water.

Only when it became clearly no longer possible to overcome the danger, did this precious gang of sailor-pirates think about what they were to do. The instinct of selfpreservation was awakened; but it was too late. They tried to empty the junk of water; the pumps were gorged, and would no longer act.

Then fear seized these bandits by the throat, and all of them, Malays, Portuguese, and Chinese, scanned the horizon wildly in search of land --- any land --- even though they might be all hanged as pirates the moment they set foot on it.

What was I doing all this time? Engaged in preserving from the mounting water my hunting weapons and nets, with the other implements I had brought from Macao, in the hope of replenishing my menagerie.

But, in the end, of what use might be all my trouble? Was I destined to escape from the critical position in which I was now placed?

On the twenty-eighth day of the vessel's voyage we had no resource but to abandon ourselves to the discretion of the tempest. The junk was left entirely to itself by Captain Ming-Ming. I do not believe, though I have been in many storms on the coast of Japan, during the voyages which I made with my father, that ever the sky and the waters were so frightfully disturbed. The old junk bounded upon the waves like an elastic ball upon a floor.

After three agonizing days, passed between life and death, we perceived a spot, black as ink, detach itself from the livid streak of the horizon. The Malays, whose eyes are gifted with an infallible power of penetration, declared that it was land, towards which we were being driven with the irresistible force of a tornado.

Night had almost immediately closed in upon us, and we had not had time to calculate whether, when the light of day reappeared, we should have reached or been carried past this land.

What a night! We had neither sails, nor masts, nor helm; and the junk was split in all directions.

At length day dawned! We looked about us: land was not more than a quarter of a mile distant from us! Chapter IV

But that quarter of a mile was composed of a chain of jagged rocks white with the foam of the sea, which broke upon them like glass furiously pulverised, and fading into space with the tenuity of ether. Impossible to avoid being broken upon them like the waves of the sea.

Little time had we for reflecting on the fate which awaited us. Two sudden and terrific shocks, following in almost instant succession, broke the back of the poor junk, the poop being at the same time carried away, and with it five of the crew. We hardly heard the cries they uttered before they were borne into the foaming abyss.

The remaining sailors, after great exertion, succeeded in launching a small boat hanging over the bulwark, with a view to endeavouring to reach the shore; but after getting her afloat, a terrible struggle ensued between them, as to which of them should get into her first. At most she was capable of containing six persons, and fifteen were attempting to invade her. Knives were drawn, and the combatants were fiercely stabbing one another, when the scene of their savagery sank under the feet of the conquered and their conquerors.

Standing apart from the rest, I at that moment caught sight of one of those buoys fastened by a light rope to the cable, and serving to show the point at which the anchor is holding beneath the water. Rapidly opening my knife I cut the rope at some distance from the cable, then seized the buoy with both arms and plunged with it into the boiling waves. For an instant drawn under water, I speedily remounted to the surface, and turned my head to see what my companions were doing. They and the last fragments of the junk had disappeared.

For three hours I struggled with death. What an agony! Each time I strove to seize hold of the points of rock shooting up between the foam and the sea, I was driven back by the retreating waves; my bleeding hands were wrenched from their painful grasp; my strength was failing me; I was barely able to retain hold of the rope attached to the buoy.

I had lost all energy, all sense of existence, when finally a great wave enveloped me and my buoy and whirled us together to the bottom of the water. I felt myself grow faint and cold; then I ceased to be conscious of anything.

When I reopened my eyes, I was lying upon a beach covered with wrack and other seaweeds, and I fancied that there were trees not very far from me. My astonishment was like that of a tipsy man awakening after a long sleep. I had not strength to rise.

The storm no longer raged. As well as I was able to judge, the sun had attained a considerable height, and was shedding a great heat upon me. The sand grew warmer and warmer under my outstretched open hands; consciousness of life returned to me, little by little. I questioned myself; I asked myself whether it was really me, and where I was. I soon acquired the certainty that I was in the neighbourhood of trees --- of a forest at no great distance off. My lethargy passed from me like a cloud. I presently rose and tried to walk a few paces; but my legs bent under me, as if they had been made of cotton-wool. However, I succeeded in holding myself erect.

Meanwhile the sun, which had been going up the sky, fell with full brightness upon the landscape. The heat of the air increased every minute, and speedily became so oppressive as to cause me to sink exhausted at the foot of a mangrove tree, the cool and refreshing shade of which, in a short time, infused a feeling of comfort into all my limbs. By degrees my eyes grew heavy with sleep, and I fell into a placid slumber.

I do not know how long I remained asleep; but when I awoke I calculated, by the decline of the sun, that it was about two o'clock in the afternoon. Judging by the sensation of rest of which I was conscious, I must have slept some seven or eight hours; but I could not be sure of this, because my watch had stopped, owing to the battering which my body had sustained before I had been washed on shore.

For the purpose of shaking off the stiffness which still remained after my long sleep, I rose and walked rapidly a few paces straight before me. I had gone but a very short distance in a direction opposite to the sea, when I saw something like a human form appear at the end of a long vista of trees which opened on my sight.

My first idea was that this was an inhabitant of the island on which I had unfortunately been wrecked; and I rejoiced at this meeting, though, at the bottom of my heart, I was not without a sense of uneasiness, as to the nature of the friend or companion sent me by fate.

Without hesitation I advanced towards this object, whatever it might be; but, after having pressed forward for some five or six minutes in the direction of the spot where I had seen it, I could see nothing of it. Had I been deceived? had a mirage of the sun caused me an hallucination? I could not explain my error, and it annoyed me extremely.

I continued to advance.

When I reached the spot where this vision had appeared to me, another horizon naturally met my view; and almost at the same moment, to my great satisfaction, I perceived the being on which I had already set eyes. Ah! how truly happy I felt. I could distinguish it even more clearly than when I had first caught sight of it, though the distance was still great which separated us. I observed it with extreme attention.

His movements appeared to me to be exceedingly active and rapid, for I noticed that he passed from one spot to another with the swiftness of a flash of lightning. The idea came into my head that he had seen me, and that my presence inspired him with alarm. Under this impression I advanced towards him with more confidence.

I had reached the very spot where I had last seen him when from a tall tree, an object undefinable at first sight --- a sort of shaggy and nervous body --- with loud, guttural and savage utterings, responded to from all distances by absolutely identical chatterings, fell at my feet. It was a monkey. At a bound the animal rose, then again threw itself down upon the ground, and ended by placing itself in the middle of my path, as if to forbid my passing.

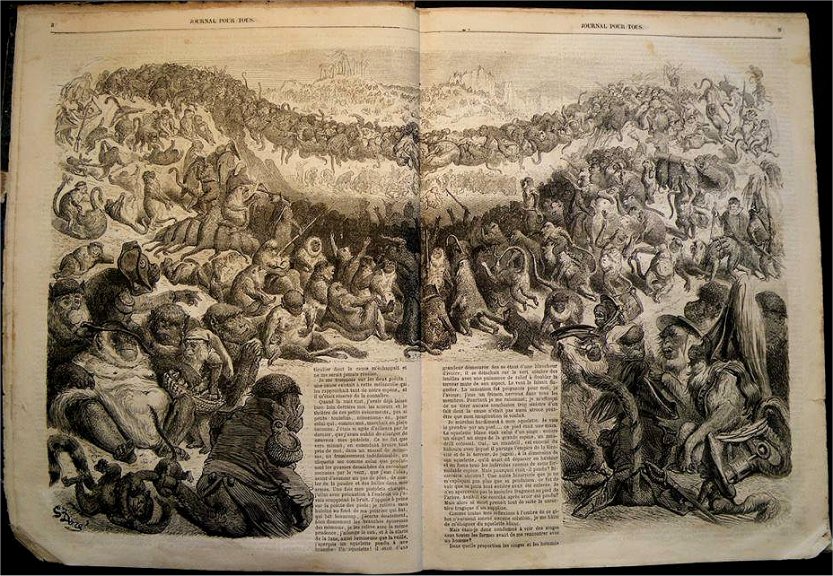

Such a pretension not being at all to my taste, I broke off the first branch that came to my hand, and threatened the brute with it. In answer, as it appeared, to a fresh outburst of chattering I saw, hastening from the four points of the horizon, glancing through the woods like gleams of light, clouds of monkeys of all shapes, colours, and sizes, who, in a moment, ran up the trees and out upon the branches, like squirrels, swarming upon all the raised points of ground about me, regarding me with their rapidly winking eyes --- all hurriedly, threateningly, hissing and grinding their teeth, in such a manner as fairly to deafen me. I was obliged to press my hands closely upon my ears to prevent my senses being shattered by the tremendous uproar of this new kind of tempest. Nothing like it, I think, had ever before been heard in the forests of Oceania.

As I had for a long time, at Macao, carried on a trade in monkeys, I easily, in spite of my agitation, recognized the different kinds I had to do with at this moment. Knowing by experience the maliciousness of these animals, when they are in large numbers, I resolved to beat a retreat; but it was too late. Behind me I saw, in eight or ten ranks closely pressed, other monkeys, some of which appeared to me to be so powerful that any attempt at flight would have been a grave imprudence on my part. I remained, therefore, where I was, but not without anxiety.

Presently the assembled monkeys began to move about me with demonstrations becoming more and more hostile, though I no longer held in my hand the unlucky branch which had been the first cause of their deep and furious irritation.

Meanwhile the heat had become overpowering at the open spot at which I was standing, and, after some time, which appeared to have modified to my advantage the disposition of my surveillants, I tried to move a few paces forward. I was, besides, horribly hungry and devoured by thirst; but I had scarcely made a movement before the groups of watchful monkeys reassembled around me, recommencing their threatening gestures, their cries, their grimacings, and their chatterings. They did even better; for they formed themselves into a square, and, when they had taken up this strategic position, of which I occupied the centre, one of them separated himself from the groups and came towards me.

Rapidly advancing, the brute snatched up the branch which I had dropped upon the sand, and, before I had time to put myself upon the defensive, rained a shower of blows upon my legs, arms, feet, head, face, back --- in short, upon every part of my body, causing me, hemmed in as I was on all sides, to spring and bound as if I had had burning coals under my feet.

I here frankly confess that I endured as much from shame as from physical pain. A vile monkey was beating me, an abominable ape was chastising me in the full light of day! Other wretched monkeys, witnesses of my moral abasement, were laughing, even writhing with delight, at the spectacle.

It was while I was thus furnishing them with this comedy, and they were affording me an opportunity for seeing them so closely, that I was struck by a singular doubt; the agitation of the moment, however, did not permit me to dwell upon it.

Ah, yes! My agitation was indeed great: flagellated by monkeys in the midst of an assemblage of monkeys! Only animals are capable of importing so much refinement into cruelty. I know that, in England as well as in France, people pay large sums of money for places to see a man executed, and that is the same at Brussels, Vienna (the capital of that philanthropic king, Josef the Second), at Berlin (the capital of a not less civilized kingdom); but, at least, we do not execute monkeys, and therefore, the right which they arrogated, of beating me, appeared --- but, for the moment, they were the stronger. It was hopeless to think of resisting them; and so I gave in to them.

The most melancholy part of the affair was that I could not see any end to the torment I was enduring; my executioner went on striking me without exhibiting the smallest sign of weariness.

Certainly, with one of the pistols which I had about me, and which it will be seen I had never been so imprudent as to divest myself during the voyage, I might easily have blown out the brains of this impudent animal; but I remembered, only too clearly, the incident which happened to the president of the Indian Company one day, when he was on an excursion in company with the famous French traveller, Tavernier, and while passing through a forest on the banks of the Ganges.

Astonished, like myself, by the great number of monkeys which he had seen suddenly gather about him, he had caused his carriage to be stopped and begged Tavernier to shoot some of them. The people in his suite, better informed as to the vindictive manners of these animals, begged him not to do anything of the sort; but the president insisted. Tavernier fired and killed a female monkey carrying her young ones.

In a moment all the other monkeys sprang, with cries of despair and fury, upon the president's carriage. They overpowered the coachman, the footmen, and the horses, and they would speedily have strangled and torn his lordship into fragments, if the carriage-blinds had not been rapidly drawn down, and if the people of his suite had not given regular battle to the assailants, of whom they disembarassed themselves only after infinite trouble.

That terrible example warned me against discharging my pistols into the body of the horrible animal, whose blows still continued to rain upon me, in spite of my anger, my rage, and the gestures I employed in defending myself. Nothing, alas! served me, and I should, assuredly, have perished under this frightful punishment, but that an idea flashed upon my mind --- an admirable idea, which, unfortunately, came very late, as excellent ideas generally come.

The keenness of my sufferings gave sharpness to my recollection, and I remembered that travellers, who had found themselves in a position similar to mine, had been able to extricate themselves by a means which I resolved to employ without a moment's delay. I unfastened my cravat and threw it, unfolded, into the midst of the assembled monkeys; it was a brilliant red cravat, bought at Bengal, the year before.

Scarcely had the monkeys perceived this sparkling piece of stuff, ere they sprang upon it with screechings of curiosity and joy. My executioner followed the general example, and I, while he and the others were disputing the prey I had thrown to them, ran away as fast as my legs would carry me, with all the strength I could bring into play, towards the interior of the island, where I counted upon meeting with some natives, and, perhaps, before then, a little water with which to quench my intolerable thirst. My hope was not completely disappointed.

After running breathlessly for a mile or two, I looked about me, and had the great satisfaction of seeing that I had not been followed by the monkeys. For more than an hour I continued my way without obstruction, over a soft sand, through groups of trees which now formed brilliantcoloured masses, now bent to the earth, as if indicating a ravine in which I might find water. I was worn out, perspiration enveloped me like a fiery mist. Should I be able to discover this ardently desired water?

On passing round a hill covered with silvery moss, I was suddenly struck by the sight of a lake at least a mile across, surrounded by tall trees, standing in rows, as if they had been so ranged by men learned in the art of laying out fancy plantations.

A gentle slope, covered with the same kind of silvery moss over which I had just passed, conducted me to the edge of the white and transparent sheet of water, so fresh in its primitive flavour as to intoxicate the drinker as completely as if it had been fermented wine!

I knelt down to drink of it, and the joy I felt in dipping my parched lips into it was so keen, so prolonged, that I must have knelt fully a quarter of an hour over this reviving beverage. My happiness was dream-like, so concentrated and silent was it. But the cry which escaped from my lips, on raising my head, was not altogether one of gratitude to Heaven, to which I owed the delicious joy of having thus refreshed my mouth and bosom: it was forced from me by surprise.

The spectacle which met my astonished gaze was this. To its entire extent the shore of the lake was covered by the same monkeys that had so pitilessly maltreated me. All had taken my kneeling attitude, all rose at the same time as myself, their muzzles moist and glittering with the water in which they had been dipped. While I imagined I had safely escaped from them, all had followed me silently through the dense borders of the forest, passing from branch to branch of the trees, from leaf to leaf, so to speak, and, on seeing me stoop to drink, all had closely imitated me. Chapter V

Though my limbs were aching with fatigue and smarting from the blows I had received, and though I was beginning to feel very seriously uneasy in my mind at finding myself constantly surrounded by this ever-increasing troop of monkeys, I could not help bursting into a loud laugh on seeing with what burlesque fidelity my least gestures, my most fugitive and involuntary movements, were copied and repeated. But I was almost seized with stupefaction on hearing my laughter instantly echoed by five or six thousand other cachinnatory explosions exactly like my own! I laughed still more loudly; they, in turn, laughed with increased loudness! It seemed as if there might be no end to the comedy.

Not understanding the meaning of this unusual disturbance, the birds, hidden in their mossy retreats, scattered in the tall ferns, swarming in the network of bindweeds spreading from tree to tree, sleeping under the leaves --- the large, the small, the invisible; birds of which their Creator alone knows the name, and of which the most gifted human tongue would find it difficult to describe the forms: birds dressed in brocade, like ancient doges, others wearing triplelace embroidered collars, like princesses of the house of Valois, others whose tail feathers look as if they were rays stolen from the sun; all arose, beating their wings, startled by that universal thunder-peal of laughter, filling the air with their flapping and whirling flight.

The monkeys themselves, though used to these outbursts on the part of the birds, were yet astonished at the strangeness and novelty of the spectacle, and all stood up to enjoy it. I then remarked something which I had not before noticed: many amongst my shaggy persecutors bore a sort of narrow red collar, for which it was at first impossible for me to account; the explanation occurred to me, however, after a short reflection. Each of those red collars was a fragment of the cravat I had abandoned to them, and which they had knotted under their chins. I have never seen anything more farcical than that ornament of toilette, with which some of them had nearly strangled themselves in their attempts to tie it securely, or to defend it against jealous comrades who had tried to deprive them of their treasure. These monkey cravats presented a sight with which I should have been delighted under any other circumstances.

My thirst I had no doubt assuaged, but my hunger remained unappeased. Far from it! for the satisfaction accorded to one sense had rendered the other more imperious. My craving for food, indeed, had been the more excited since, for about a quarter of an hour, I had caught sight of some trees growing on the shore of the lake, from which were hanging some kind of golden-coloured fruit, delicious to look upon, and doubtless more delicious to eat, but growing so high, so very high, so near to the summit of the trees, that no man, not even a Japanese sailor, could ever have succeeded in plucking them without the aid of a ladder. Trees from one hundred and eighty to two hundred feet high, without bark, without branches, without the least unevenness upon their trunks, not a resting-place of any sort for more than half of their entire height.

Hungrily my eyes feasted upon those fruits, my stomach wooed them with the tenderest yearnings; --- but how to get them! The thing was impossible. I tried, however, after many vain calculations, to throw a sharp stone with all the force I could command, in the bare hope of detaching them. I was not unskilful in this kind of exercise, and succeeded in touching the tree at which I had thrown, but I failed to dislodge any of its golden fruit.

After striking, the stone, of its own weight, fell from branch to branch with a great noise --- the smallest sound is magnified in these islands, where man has not destroyed the primitive silence --- bringing down with it a shower of withered leaves. But almost before it reached the ground the monkeys, who had eagerly followed all my movements, from the moment of my kneeling down to drink in the lake, fell to picking up all the stones they could find within their reach and throwing them at the upper branches of the trees.

Oh, the din, the crash, the hail, the rattle, of their attack! No destruction could possibly be more rapidly effected. They made a chain and passed stones from hand to hand, so that the throwers should not have to wait for missiles. Stories are told of whole fields of maize being devoured in the course of a few hours by the locusts of Libya; in a few minutes fruit, leaves, branches were stripped from the group of trees, the midst of which my stone had so ineffectively pierced; and those thousands of fruits, those piles of leaves, those heaps of creepers, this maze of branches, fallen upon the shore of the lake, so encumbered it that I had but to put out my hand to seize upon the fruit I so eagerly longed for.

It may readily be imagined that I lost no time-in doing this, but the moment the monkeys, to whom I owed this abundant provision, saw me raise one of the fruits to my mouth, the whole of them instantly copied me. Thousands of arms were raised to thousands of mouths, the manoeuvre being executed as by military command, and with the precision of Prussian discipline. I raised my elbow, all the elbows of the monkeys were raised. I cast away a fruit stone, in a moment the air was filled with rejected fruit stones. The echoes of the lake presently repeated nothing but the clatter of their teeth, and its surface almost entirely disappeared under the refuse of the fruit sucked and devoured with this burlesque unanimity and imperturbable imitation.

Though I was now delivered to all the chances of fortune and destiny, escaping from one danger only to fall into another still worse perhaps, I nevertheless desired to get free from the odious imprisonment in which I was held by these abominable creatures. Moreover, it, was not without alarm that I saw the daylight fading and night approaching. I dreaded finding myself alone in the midst of darkness with these legions of demons, whose fantastic surprises have not even human imagination for their limits. For our imagination is not a shadow of theirs; our impossible is reality to them. They are creatures eternally mad, to whom our madness is pure reason.

What would happen to me? Night --- and them! Doubtless, I should, next day, discover some natives, for this was not a desert island; doubtless, I should be able to reach the centre of the island, where, probably, their houses were built; but, meanwhile, I had to pass this dreaded night.

In my feverish anxiety, sharpened by the knowledge which I possessed of all these evil geniuses, the idea came to me --- in view of the fact of their eagerness to do everything I did --- to make believe to go to sleep. If I were clever enough to get them to imitate me to the extent of going to sleep, I might profit by their lethargy to escape from their surveillance and penetrate into the heart of the island. It is true that I was ignorant as to its configuration; but, during a night's march, I might, no doubt, be able to put ten or twelve leagues between them and me. The plan appeared to me to be a good one, and I at once carried it into execution.

I began by collecting some armfuls of dry leaves, and performed this preliminary operation with as much noise as possible, with the object of provoking the imitative attention of my spies. In this intention I was perfectly successful; for, instantly, the whole assembly set to work with the most comic eagerness, gathering heaps of dry leaves of the tulip tree, and spreading them upon the ground, as they saw me doing.

Delighted with this commencement, I heaped a considerable quantity of my leaves at the foot of a tree, which I had selected for a back-rest. They all immediately did the same. When I had thoroughly completed my arrangements, I stretched myself upon my bed and watched. But this time my imitators did not move. A bad sign!

There was, clearly, a hitch in the development of the calculation I had made for leading them into a trap. With paws plunged in the dry leaves, bodies held erect, muzzles turned towards me, and eyes glaring at me, they examined me, following the least movements of my body; but not one of them lay down. Were they beginning to distrust me? Pursuing my purpose, so as to be enabled to learn exactly what I had to expect, I stretched forth my arm, like a man falling off to sleep. I yawned with open mouth, and, finally, shut my eyes. Of these three acts, they only imitated one: they yawned to the very depths of their jaws; but that was all.

It was of no use keeping my eyes closed, they kept theirs constantly open. I carried the intended deception so far as to snore; it was unavailing: not a monkey, large or small, yellow, black, or green, was taken in.

Both they and I remained on guard.

It was at that moment that the doubt which had come into my mind while I was being bastinadoed again returned to it. I distinguished amongst the crowd of monkeys so attentively watching my movements, certain visages which were not unknown to me; but, as I had previously done, I put aside this strange perception, which could only have resulted from the troubled state of my brain, and from the common resemblance which these animals bear to each other. Chapter VI

During the space of a quarter of an hour-and such quarters of an hour seem like ages --- I had played this comedy of sleep, which, to my despair, did not make a solitary dupe, when, through my slightly opened eyes, I perceived two of the largest monkeys of the band approaching me. They were coming, not walking on all fours on the sand, but as they move from place to place in their wandering and vagabond life in the midst of woods, by springing from tree to tree and branch to branch, as noiselessly as birds.

Arrived immediately above my head --- it may readily be conceived that I had not lost sight of them for a single moment --- they slid quietly down the trunk of the tree to the ground; on reaching which, they passed, with the same noiseless precaution, one to my right, the other to my left side. In that position they remained motionless for several minutes.

I had to do with two hideous ourang-outangs, and both revealed their prodigious strength and agility by their thickset bodies, closely-knit and nervous limbs. From these characteristics I judged that they would easily get the better of ten unarmed men. After having observed, studied, and, so to speak, reckoned me up, with a gravity at once farcical and magisterial, as if to assure themselves that I was really asleep, one of them placed himself at my feet.

The ourang-outang on my right hand began by smelling me under the nose, after the manner of wild beasts: he then parted my hair attentively, curiously, from my forehead to the top of my head, with minute, delicate, excessive care; above all with intentions which my absolute state of personal cleanliness rendered wholly illusory. The Spanish boy, in Murillo's sublime and repulsive picture might have replaced me with advantage. Ah, how much I desired to see him in my place! For this total absence of reward for the pains taken by my ourang-outang led me to fear that, suddenly changing his line of conduct, he might, with a claw of one of his terrible hands, armed with nails of steel, strip off the entire hair and skin from my head, as the Red Indians, elder brothers of monkeys, scalp their victims.

While one of the ourang-outangs was affording me this perilous emotion, the other divested me of my shoes and amused himself, with the simplicity of a child wishing at any price to ascertain how and why her doll raises or lowers its arms on a spring being pressed, by bending and straightening my toes, appearing greatly astonished, and almost indignant, at finding that a man was as well constructed as a monkey.

Unfortunately for me, he took so much pleasure in this amusement as to finish by pulling off my stockings, which he immediately attempted to apply to his own use, but with no great success. Yes! I confess that the attention to my person exhibited by those two valets de chambre caused me frightful agony of mind --- which was redoubled when the ourang-outang which was at my feet, having no doubt had his taste excited by my stockings, wished to pull off my trousers.

I should have allowed him to carry out his intention, but the ourang-outang who was at my head opposed it with all his might, desiring to secure the garment for himself. Little by little the struggle became dark and furious. One by one I felt the buttons give way under the abnormal stress put upon them. Then I heard the sound of a rent in the cloth, and foresaw that speedily, under the efforts of these two formidable antagonists, the field of battle would be my own body --- my body which would feel the impression of their iron teeth, their harpy-like claws, a prey to their pitiless instinct of destructiveness. It was my sentence of death.

Before dying, however, I wished to make at least an effort to preserve my life. I slipped a hand into each of my trousers' pockets and drew my pistols from them without awaking the least suspicion. At the same instant, for events moved rapidly, I pointed the muzzle of one pistol towards my feet, the other towards my head, and made ready to kill my persecutors, though I felt sure that their death would be immediately followed by my own --- the fate which would overtake me after this double murder not being in the least doubtful; the two or three hundred monkeys assisting as actors or witnesses in the scene would rend me into a larger number of pieces than they had torn my cravat.

Moment by moment the final instant approached --- it arrived --- it was come. The seat of my trousers cracked. I pressed my fingers on the triggers.

A whistle, a screech, resounded! --- such a sound as only a locomotive with its breath of fire could send abroad from its iron chest, rang from echo to echo, like thunder in the depths of a valley. I opened my eyes: not a monkey --- not one --- was near me. I saw them flying --- flying with the swiftness of a bullet shot from a cannon; flying towards the same point; flying so as, presently, to offer to my sight nothing but thousands upon thousands of tails painting the horizon, and finally purging it of their abominable presence.

All had disappeared. I heard, dying away in the distance, the nervous grinding of their teeth, with which they appeared to excite themselves to triple rapidity of motion. Even this sound died out at last, until it became no more than the pulsation heard in the ears, when the blood is coursing from the heart. At last all became silent. The air was free, the earth had regained its serenity, as after the clearing off of a fetid mist.

I had risen to my feet, I breathed again, I was revived. But whence had come that formidable sound? from what tremendous chest had it issued? Was it a leopard wounded to death? a tiger in the pains of love? a man? What had it expressed? what meaning had it conveyed, that had been so generally understood? How could I learn this? to whom could I apply for information?

In the blink of an eye, solitude and silence had taken the place of frightful tumult, of savage and grotesque scenes, of which that mysterious sound had marked either the dénouement or the entr'acte; for what, in reality, was the meaning of the spontaneous disappearance of all those monsters, as by the interposition of a miracle --- an end, or only a suspension, of hostilities?

Night was advancing --- it was come. What was I to do? what was to become of me, in the midst of this unknown island, the possible inhabitants of which were the more frightful to my mind from the persistent way in which they hid themselves from my sight?

I should have been very glad to have remained until the next day at the spot where I was standing; but had I not to fear seeing my enemies return --- to see them return more determined than ever to torment me with their inexhaustible malignity, especially as now they knew how superior to me they were in audacity and strength? On the other hand, whither could I go, without exposing myself to the peril of being devoured by thousands of dangerous animals scattered in these woody labyrinths --- furze bushes growing higher than my head, and colossal roots --- gliding, swelling with venom, under all these vegetations monstrous as themselves?

My fluctuations of mind threw me into a burning fever. The beating of my heart sounded in my brain like the booming of a great bell, like the crash of the sea as one approaches it. This tumult of my blood made me, at moments, believe that I really heard distant voices, rising from the midst of large centres of population --- the same as I heard when in the country about Goa and Macao.

People who are wrecked have these kind of sickly hallucinations.

During this moment of my delirium, a red line suddenly tinged the horizon and parted it --- like the passing of a knife through the peel of a pomegranate. Then, at a point upon the edge of this red line, a globe of fire appeared and mounted the sky majestically. was the nearly full moon rising. Chapter VII

I thought that she rose for me alone, such was the calm she brought to my agitated spirits, by inundating me with her beautiful light. Her rays gave hope to my soul, and, to my eyes a smile from heaven. I regained courage. My blood redescended from my brain into my veins. I reasoned lucidly upon my situation, and proved to myself that I had no serious reason for remaining longer on the spot where I was.

My resolution was taken. With my knife I cut the strongest bamboo stem I could find on the edge of the lake, to use as a defensive arm; and I then set out to learn whether this vast, piece of fresh water had, as was presumable, any exterior outlet. That was a geological fact which it was of the highest importance to me to determine.

Great watercourses --- though there were some notable exceptions in Oceania --- all run into the sea; and if this lake, on the margin of which I was advancing had any important stream running from it, I was certain that by following it step by step, I should come to the sea. Moreover, as it rarely happens that the banks of these streams do not form the land-lines on which the inhabitants, urged by the instinct of need, erect their huts or their villages, I was equally certain of finding on my way some of these villages, huts, or inhabitants.

With the object, therefore, of discovering this outflow, if it existed, I set to work to explore closely the entire circumference of the lake, in spite of the jungles which interfered to turn aside my steps.

After pressing forward for about an hour, I was stopped by a confused noise. I listened with all my ears, then moved forward towards the sound, which became more distinct. I concentrated my attention, and at last was led almost in a straight line by the freshness and loud murmur of a waterfall of considerable volume. It was what I was seeking. The waters of the lake poured themselves into a lower basin, contracted themselves a little further on, and then became the stream or river on which I had counted. I followed the course of this natural canal, but not without stumbling upon strange difficulties.

Oh, no; it was not so easy a thing as may be imagined to continue one's way for any length of time along a bank at one place formed only of withered vegetable matter, so spongy, that sometimes it was wholly impossible to set foot upon it without sinking up to one's knees; at another spot the ground was entirely hidden many feet deep by a network composed of the matted fibres of bamboos, mimosas, and trailing plants --- tissues which had tenaciously crossed and recrossed one another during ages, and spread from shore to shore of the stream, forming a vault under which I could not pass, save by crawling.

It was while moving through one of these dark places in this manner, that, in putting my hand upon the ground to support myself, I seized hold of a roll of something cold as ice, while at the same moment I was struck in the face by a flapping wing: a double sensation --- a double horror! The icy roll was a serpent; the blow came from the clammy wings of an enormous bat. I even now shudder at the recollection of that frightful encounter.

For ten hours I advanced in this way towards an unknown point, but more and more persuaded as I proceeded that the part of the island I was exploring, under the perilous conditions I have tried to describe, was uninhabited; unless, indeed, it contained other lakes and other streams --- an eventuality highly doubtful, because of the limited extent of the groups of islands in the midst of which I had been wrecked. If I was thus forced to conclude that no inhabitants would be likely to appear at any distance from this stream, upon the banks of which no dwelling-place was visible, I was further compelled, by the same authority of reasoning, to conclude that neither did the island contain any wild beasts, who, it is known from the evidence of travellers, prefer the oozy margins of rivers, where they are sure to find, during the scorching hours of the day, abundant shade, also plenty of prey, and, at night, inviolate retreat.

When, at length, I got an uninterrupted view of the sky to the extent of several leagues to my right and left, day was beginning to dawn. The violent exercise I had taken, joined to the sudden bracingness of the air, added to the very slight meal I had taken many hours before --- for the fruit I had eaten, good and agreeable enough to the taste as they were, were not very sustaining to the civilized stomach --- had aroused within me the appetite of a tiger. I never before so much regretted that Providence had not reserved for us, for difficult occasions, the ability to live upon grass like some meaner animals, or provided us, like some others, with the means of seizing our prey with our hands. Formerly, in the primitive ages of the world, we may, perhaps, have had an organization less exclusive; but, however that may be, here was I, dying of hunger in the midst of this paradise of plants, of ferns, of magnificent roots, which would have been the delight of a horse or an ox.

While I was given up to these reflections, daylight dawned and steadily increased; objects began to detach themselves sharply from the tender violet background, tinted with yellow, the precursor of morn in Oceania and Southern China. A fresh breeze swept over the ground, and from its keenness and temper, if I may employ such an image, I felt that it had passed over the sea. The sea, I could have wagered, was not far off. Other signs assured me of this: the trees were less tufted, less spreading; the furze bushes, more compact and shorter, also became more rare. When the sun mounted, I should only have to cry: "There's the sea!" And that was what I presently said.

The sea was not more than two hundred paces from me when I caught sight of its wavelets, the same waves that had dashed so furiously yesterday, whitening an entire arc of the coast. Supposing some regularity to belong to the form of the island, this arc indicated, according to my calculation, a circumference of thirty leagues. Again, admitting, as I was bound to do from observation, that the distance I had travelled during the night was half the diameter of the entire island, that is to say, five leagues, the circumference would be, as I had guessed, about thirty leagues, the average of the islands amongst which I had been cast.

After having thus assured myself that the half of the island I was on was not inhabited, at least along the course of the stream I had explored, I was still, however, in hopes that I might find some natives on the sea-shore, especially if they were either fishermen, a profession common in Malaya; or traded in exchange, not so common a profession; or, finally, pirates, a profession which accompanies all the others in these violent countries.

I began my excursion along the sea-shore, in spite of the fatigue with which I was nearly overcome; but I had no time to lose, for the heat of the sun, once mounted in the heavens, renders all bodily exertion impossible under the vault of this white-glowing zone.

Though during the first three miles I saw no more inhabitants than I had previously seen, I at least became assured that my good friends of the night before --- the monkeys --- did not often visit this side of the island. The indications from which I formed this conclusion were these: Thousands of oysters were scattered about the beach, and two-thirds of them, at least, were open, not naturally, but owing to the insertion of a small stone between their two shells. Who had opened them in this way? My monkeys.