Volume 1898b

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

|

|

|

|

| Chapter XIII. | Moses - His Capture - His Character - His Affections - His Food - His Daily Life - Anecdotes of Him |

| Chapter XIV. | The Character of Moses- He Learns a Human Word- He Signs - His Name to a Document - His Illness- Death |

| Chapter XV. | Aaron - His Capture - Mental powers - Acquaintance with Moses - His Conduct during Moses' Illness |

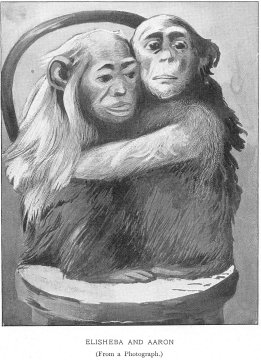

| Chapter XVI. | Aaron and Elisheba - Their Characteristics - Anecdotes - Jealousy of Aaron |

| Chapter XVII. | Illness of Elisheba - Aaron's Care of Her - Her Death - Illness and Death of Aaron |

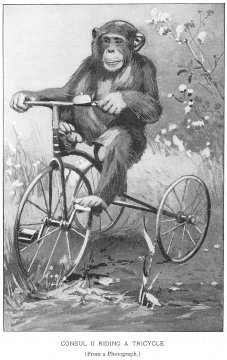

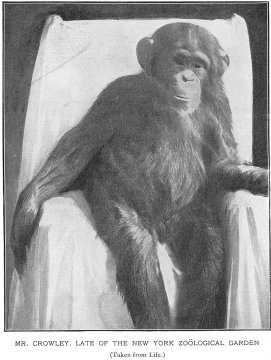

| Chapter XVIII. | Other Chimpanzees - The Village Pet - A Chimpanzee as Diner-Out - Notable Specimens in Captivity |

| Chapter XIX. | Other Kulu-Kambas - A Knotty Problem - Instinct or Reason - Various Types |

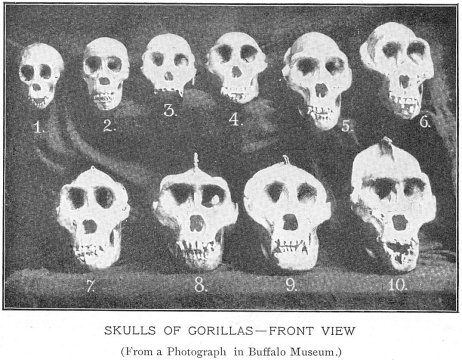

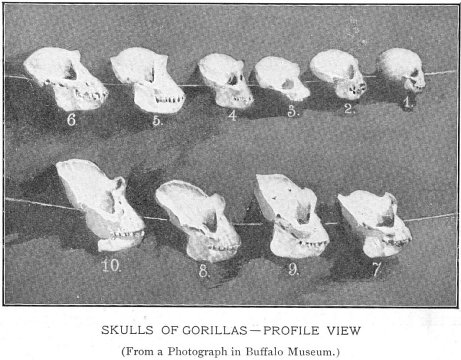

| Chapter XX. | The Gorilla- His Habitat Skeleton - Skull - Color - Structural Peculiarities |

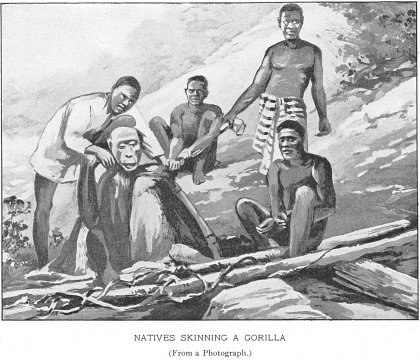

| Chapter XXI. | Habits of the Gorilla - Social Traits - Government - Justice - Mode of Attack - Screaming and Beating - Food |

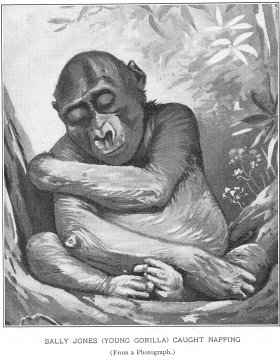

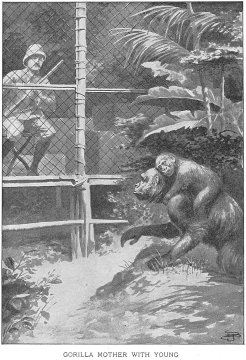

| Chapter XXII. | Othello and Other Gorillas - Othello and Moses - Gorilla Visitors - Gorilla Mother and Child - Scarcity of Gorillas - Unauthentic Tales |

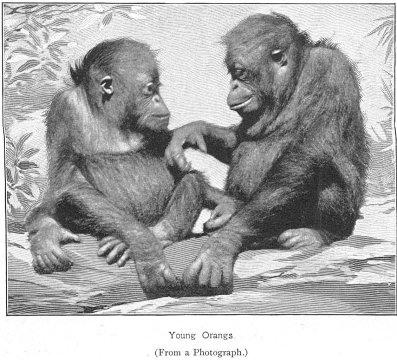

| Chapter XXIII. | Other Apes - The Apes in History - Habitat - The Orangs - The Gibbon |

| Chapter XXIV. | The Treatment of Apes in Captivity - Temperature - Building - Food - Occupation |

During

my sojourn in the forest I had a fine young chimpanzee, which was of ordinary

intelligence, and he was of more than ordinary interest, because of his

history. I gave him the name Moses, -- not in derision of the historic

Israelite of that name, but owing to the circumstances of his capture and

his life. He was found all alone in a wild papyrus swamp of the Ogow‚ River.

No one knew who his parents were. The low bush in which he was crouched

when discovered was surrounded by water, and thus the poor little waif

was cut off from the adjacent dry land. As the native approached to capture

him, the timid little ape tried to climb up among the vines above him and

escape; but the agile hunter seized him. At first the chimpanzee screamed

and struggled to get away, because he had perhaps never before seen a man;

but when he found that he was not going to be hurt, he put his frail arms

around his captor and clung to him as a friend. In deed, he seemed glad

to be rescued from such a dreary place, even by such a strange creature

as a man. For a moment the man feared that the cries of his young prisoner

might call its mother to the rescue, and possibly a band of others; but

if she heard, she did not respond; so he tied the baby captive with a thong

of bark, put him into a canoe, and brought him away to the village. There

he supplied him with food and made him quite cosy. The next clay he was

sold to a trader. About this time I passed up the river on my way to the

jungle in search of the gorilla and other apes. Stopping at the station

of the trader, I bought the young chimpanzee and took him along with me.

We soon became the best of friends and constant companions.

During

my sojourn in the forest I had a fine young chimpanzee, which was of ordinary

intelligence, and he was of more than ordinary interest, because of his

history. I gave him the name Moses, -- not in derision of the historic

Israelite of that name, but owing to the circumstances of his capture and

his life. He was found all alone in a wild papyrus swamp of the Ogow‚ River.

No one knew who his parents were. The low bush in which he was crouched

when discovered was surrounded by water, and thus the poor little waif

was cut off from the adjacent dry land. As the native approached to capture

him, the timid little ape tried to climb up among the vines above him and

escape; but the agile hunter seized him. At first the chimpanzee screamed

and struggled to get away, because he had perhaps never before seen a man;

but when he found that he was not going to be hurt, he put his frail arms

around his captor and clung to him as a friend. In deed, he seemed glad

to be rescued from such a dreary place, even by such a strange creature

as a man. For a moment the man feared that the cries of his young prisoner

might call its mother to the rescue, and possibly a band of others; but

if she heard, she did not respond; so he tied the baby captive with a thong

of bark, put him into a canoe, and brought him away to the village. There

he supplied him with food and made him quite cosy. The next clay he was

sold to a trader. About this time I passed up the river on my way to the

jungle in search of the gorilla and other apes. Stopping at the station

of the trader, I bought the young chimpanzee and took him along with me.

We soon became the best of friends and constant companions.

It was supposed that the mother chimpanzee had left her babe in the tree while she went off in search of food, and had wandered so far away that she lost her bearings and could not again find him. He appeared to have been for a long time without food, and may have been crouching there in the forks of that tree for a day or two; but this was only inferred from his hunger, as there was no way to determine how long he had remained, or even how he got there.

I designed to bring Moses up in the way that good chimpanzees ought to be brought up; so I began to teach him good manners, in the hope that some day he would be a shining light to his race, and aid me in my work among them. To that end I took great care of him, and devoted much time to the study of his natural manners, and to improving them as much as his nature would allow.

I built him a neat little house within a few feet of my cage. It was

enclosed with a thin cloth, and at the door I hung a curtain to keep out

mosquitoes and other insects. It was supplied with plenty of soft, clean

leaves, and some canvas bed-clothing. It was covered over with a bamboo

roof, and was suspended a few feet from the ground, so as to keep out the

ants.

Moses soon learned

to adjust the curtain and go to bed without my aid. He would lie in bed

in the morning until he heard me or the boy stirring about the cage, when

he would poke his little black head out and begin to jabber for his breakfast.

Then he would climb out and come to the cage to see what was going on.

He was not confined at all, but quite at liberty to go about in the forest,

climb the trees and bushes, and have a good time of it. He was jealous

of the boy, and the boy was jealous of him, especially when it came to

a question of eating. Neither of them seemed to want the other to eat anything

that they mutually liked, and I had to act as umpire in many of their disputes

on that grave subject, which seemed to be the central thought of both of

them. I frequently allowed Moses to dine with me, and I never knew him

to refuse, or to be late in coming, on such occasions; but his table etiquette

was not of the best order. I gave him a tin plate and a wooden spoon. He

did not like to use the latter, but seemed to think that it was pure affectation

for any one to eat with such an awkward thing. He always held it in one

hand while he ate with the other or drank his soup out of the plate. It

was such a task to get washing done in that part of the world, that I resorted

to all means of economy in that matter, and for a tablecloth I used a leaf

of newspaper, when I had one. To tear that paper afforded Moses an amount

of pleasure that nothing else would, and in this act his conduct was more

like that of a naughty child than in anything else he did. When he would

first take his place at the table, he would behave in a nice and becoming

manner; but having eaten till he was quite satisfied, he usually became

rude and saucy. He would slyly put his foot up over the edge of the table,

and catch hold of the corner of the paper, meanwhile watching me closely,

to see if I was going to scold him. If I remained quiet, he would tear

the paper just a little and wait to see the result. If no notice was taken

of that, he would tear it a little more, but keep watching my face to see

when I observed him. If I raised my finger to him, he quickly let go, drew

his foot down, and began to eat. If nothing more was done to stop him,

the instant my finger and eyes were dropped, that dexterous foot was back

on the table and the mischief was resumed with more audacity than before.

When he carried his fun too far, I made him get down from the table and

sit on the floor. This humiliation he did not like, at best; but when the

boy grinned at him for it, he would resent it with as much temper as if

he had been poked with a stick. He certainly was sensitive on this point,

and evinced an undoubted dislike to being laughed at.

Moses soon learned

to adjust the curtain and go to bed without my aid. He would lie in bed

in the morning until he heard me or the boy stirring about the cage, when

he would poke his little black head out and begin to jabber for his breakfast.

Then he would climb out and come to the cage to see what was going on.

He was not confined at all, but quite at liberty to go about in the forest,

climb the trees and bushes, and have a good time of it. He was jealous

of the boy, and the boy was jealous of him, especially when it came to

a question of eating. Neither of them seemed to want the other to eat anything

that they mutually liked, and I had to act as umpire in many of their disputes

on that grave subject, which seemed to be the central thought of both of

them. I frequently allowed Moses to dine with me, and I never knew him

to refuse, or to be late in coming, on such occasions; but his table etiquette

was not of the best order. I gave him a tin plate and a wooden spoon. He

did not like to use the latter, but seemed to think that it was pure affectation

for any one to eat with such an awkward thing. He always held it in one

hand while he ate with the other or drank his soup out of the plate. It

was such a task to get washing done in that part of the world, that I resorted

to all means of economy in that matter, and for a tablecloth I used a leaf

of newspaper, when I had one. To tear that paper afforded Moses an amount

of pleasure that nothing else would, and in this act his conduct was more

like that of a naughty child than in anything else he did. When he would

first take his place at the table, he would behave in a nice and becoming

manner; but having eaten till he was quite satisfied, he usually became

rude and saucy. He would slyly put his foot up over the edge of the table,

and catch hold of the corner of the paper, meanwhile watching me closely,

to see if I was going to scold him. If I remained quiet, he would tear

the paper just a little and wait to see the result. If no notice was taken

of that, he would tear it a little more, but keep watching my face to see

when I observed him. If I raised my finger to him, he quickly let go, drew

his foot down, and began to eat. If nothing more was done to stop him,

the instant my finger and eyes were dropped, that dexterous foot was back

on the table and the mischief was resumed with more audacity than before.

When he carried his fun too far, I made him get down from the table and

sit on the floor. This humiliation he did not like, at best; but when the

boy grinned at him for it, he would resent it with as much temper as if

he had been poked with a stick. He certainly was sensitive on this point,

and evinced an undoubted dislike to being laughed at.

Another habit that Moses had was putting his fingers in the dish to help himself. He had to be watched all the time to prevent this, and seemed unable to grasp any reason why he should not be allowed to do so. He always appeared to think my spoon, knife, and fork were better than his own. On one occasion he persisted in begging for my fork until I gave it to him. He dipped it into his soup, held it up, and looked at it as if disappointed. He again stuck it into his soup. Then he examined it, as if to see how I lifted my food with it. He did not seem to notice that I used it in lifting meat instead of soup. After repeating this three or four times he licked the fork, smelt it, and then deliberately threw it on the floor, - as if to say, "That's a failure." He then leaned over and drank his soup from the plate.

The only thing that he cared much to play with was a tin can in which I kept some nails. For this he had a kind of mania. He never tired of trying to remove the lid. When given the hammer and a nail, he knew what they were for, and would set to work to drive the nail into the floor of the cage or into the table; but he hurt his fingers a few times, and after that he stood the nail on its flat head, removed his fingers, and struck it with the hammer; but of course he never succeeded in driving it into anything.

A bunch of sugarcane was kept for Moses to eat when he wanted it. To aid him in tearing the hard shell away from it, I kept a club to bruise it. Sometimes he would go and select a stalk of cane, carry it to the block, take the club in both hands, and try to mash the cane; but as the jar of the stroke often hurt his hands, he learned to avoid this by letting go as the club descended. He never succeeded in crushing the cane, but would continue his efforts until some one came to his aid. At other times he would drag a stalk of the cane to the cage and poke it through the wires, then bring the club and poke it through to get me to mash the cane for him.

From time to time I received newspapers sent me from home. Moses could not understand what induced me to sit holding that thing before me, but he wished to try it and see. He would take a leaf of it, and hold it up before him with both hands, just as he saw me do; but instead of looking at the paper, he kept his eyes, most of the time, on me. When I turned my paper over, he did the same thing with his, but half the time it was upside down. He did not appear to care for the pictures, or notice them, except a few times he tried to pick them off the paper. One large cut of a dog's head, when held at a short dis tance from him, he appeared to regard with a little interest, as if he recognized it as that of an animal of some kind; but I cannot say just what his ideas concerning it really were.

Chimpanzees are not usually so playful or so funny as monkeys, but they have a certain degree of mirth in their nature, and at times display a marked sense of humor. Moses was fond of playing peek-a-boo. He did not try to conceal his body from view, but put his head behind a box or something to hide his eyes. Then he would cautiously peep at me. He would often put his head behind one of the large tin boxes in the cage, leaving his whole body visible. In this attitude he would utter a peculiar sound, then draw his head out and look to see if I were watching him. If not, he would repeat the act a few times and then resort to some other means of amusing himself. But if he could gain attention the romp began. He found great pleasure in this simple pastime. He would roll over, kick up his heels, and grin with evident delight. His favorite hour for this sport was in the early part of the afternoon. I spent much time in entertaining him in this way and in many others, feeling amply repaid by the gratification it afforded him. I could not resist his overtures to play, as he was my only companion; and, living in that solitary manner, we found mutual pleasure in such diversions.

Another occasion on which he used to peep at me was when he lay down to take his midday nap. For this I had made him a little hammock. It was suspended by wires hooked in the top of my cage, so as to be removable when not in use. I always hung this near me, so I could swing him to sleep like a child. He liked this very much, and I liked equally well to indulge him in it. When he was laid in this little hammock, he was usually covered up with a small piece of canvas, and in spreading it over him I sometimes laid the edge of it over his eyes. But this caused him to suspect me of having some motive in doing so. Then he would reach his finger up, catch the edge of the cloth and gently draw it down, so as to see what I was doing. If he found that he was detected, he quickly released the cloth, and cuddled down as though he had drawn it down by accident; but the little rogue knew just as well as I did that it was not fair to peep.

I also made him another hammock, which was hung a few yards from the cage. It was intended that he should get into this without bothering me. But he did not seem to care for it, until I brought a young gorilla to live with us in our jungle home. As Moses had never used this hammock, I assigned it to the new member of the household. Whenever the gorilla got into the hammock there was a small row about it. Moses would never allow him to occupy it in peace. He seemed to know that it was his own by right, and the gorilla was regarded as an intruder. He would push and shove the gorilla, grunt and whine and quarrel until he got him out of it. But after doing so he would leave the hammock and climb up into the bushes, or go scouting about, hunting something to eat. He only wanted to dispossess the intruder, for whom he nursed an inordinate jealousy. He never went about the gorilla's little house, which was near another side of my cage. Even after the gorilla died Moses kept aloof from its house.

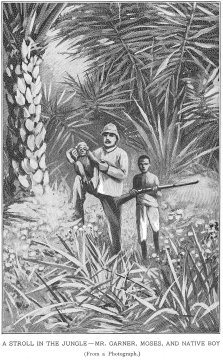

As a rule, I took Moses with me in my rambles into the forest, and I found him to be quite useful in one way. His eyes were like the lens of a camera; nothing escaped them. When he discovered anything in the jungle, he always made it known by a peculiar sound. He could not point it out with his finger, but by watching his eyes the object could often be located. Frequently during these tours the ape rode on my shoulders. At other times the boy carried him; but occasionally he was put clown on the ground to walk. If we traveled at a very slow pace, and allowed him to stroll along at leisure, he was content to do so; but if hurried beyond a certain gait, he always made a display of temper. He would turn on the boy and attack him if possible; but if the boy escaped, the angry little ape would throw himself down on the ground, scream, kick, and beat the earth with his own head and hands, in the most violent and persistent manner. He sometimes did the same way when not allowed to have what he wanted. His conduct was exactly like that of a spoiled or ugly child.

He had a certain amount of ingenuity, and often evinced a degree of reason which was rather unexpected. It was not a rare thing for him to solve some problem that involved a study of cause and effect, but this was always in a limited degree. I would not be understood to mean that he could work out any abstract problem, such as belongs to the realm of mathematics, but only simple, concrete problems, the object of which was present.

On one occasion while walking through the forest, we came to a small stream of water. The boy and myself stepped across it, leaving Moses to get over without help. He disliked getting his feet wet, and paused to be lifted across. We walked a few steps away and waited. He looked up and down the branch [sic] to see if there was any way to avoid it. He walked back and forth a few yards, but found no way to cross. He sat down on the bank and declined to wade. After a few moments he waddled along the bank about ten or twelve feet to a clump of tall, slender bushes growing by the edge of the stream. Here he halted, whined, and looked up thoughtfully into them. At length he began to climb one of them that leaned over the water. As he climbed up, the stalk bent with his weight, and in an instant he was swung safely across the little brook. He let go the plant, and came hobbling along to me with a look of triumph on his face that plainly indicated he was fully conscious of having performed a very clever feat.

One dark, rainy

night I felt something pulling at my blanket and mosquito bar. I could

not for a moment imagine what it was, but knew that it was something on

the outside of my cage. I lay for a few seconds, and then I felt another

strong pull. In an instant some cold, damp, rough thing touched my face.

1 found it was his hand poked through the meshes and groping about for

something. I spoke to him, and he replied with a series of plaintive sounds

which assured me that something must be wrong. I rose and lighted a candle.

His little brown face was pressed up against the wires, and wore a sad,

weary look. He could not tell me in words what troubled him, but every

sign, look, and gesture bespoke trouble. Taking the candle in one hand

and my revolver in the other, I stepped out of the cage and went to his

domicile. There I discovered that a colony of ants had invaded his quarters.

These ants are a great pest when they attack anything, and when they make

a raid on a house the only thing to be done is to leave it until they have

devoured everything about it that they can eat. When they leave a house

there is not a roach, rat, bug, or insect left in it. As the house of Moses

was so small, it was not difficult to dispossess the ants by saturating

it with kerosene. This was quickly done, and the little occupant was allowed

to return and go to bed. He watched the procedure with evident interest,

and seemed perfectly aware that I could rid him of his savage assailants.

In a wild state he would doubtless have abandoned his claim and fled to

some other place, without an attempt to drive the ants away; but in this

instance he had acquired the idea of the rights of possession.

One dark, rainy

night I felt something pulling at my blanket and mosquito bar. I could

not for a moment imagine what it was, but knew that it was something on

the outside of my cage. I lay for a few seconds, and then I felt another

strong pull. In an instant some cold, damp, rough thing touched my face.

1 found it was his hand poked through the meshes and groping about for

something. I spoke to him, and he replied with a series of plaintive sounds

which assured me that something must be wrong. I rose and lighted a candle.

His little brown face was pressed up against the wires, and wore a sad,

weary look. He could not tell me in words what troubled him, but every

sign, look, and gesture bespoke trouble. Taking the candle in one hand

and my revolver in the other, I stepped out of the cage and went to his

domicile. There I discovered that a colony of ants had invaded his quarters.

These ants are a great pest when they attack anything, and when they make

a raid on a house the only thing to be done is to leave it until they have

devoured everything about it that they can eat. When they leave a house

there is not a roach, rat, bug, or insect left in it. As the house of Moses

was so small, it was not difficult to dispossess the ants by saturating

it with kerosene. This was quickly done, and the little occupant was allowed

to return and go to bed. He watched the procedure with evident interest,

and seemed perfectly aware that I could rid him of his savage assailants.

In a wild state he would doubtless have abandoned his claim and fled to

some other place, without an attempt to drive the ants away; but in this

instance he had acquired the idea of the rights of possession.

Moses was especially fond of corned beef and sardines, and would recognize a can of either as far away as he could see it. He also knew the instrument used in opening the cans. But he did not appear to appreciate the fact that when the contents had once been taken out it was useless to open the can again; so he often brought the empty cans that had been thrown into the bush, got the can-opener down, and wanted me to use it for him! I never saw him try to open a can himself otherwise than with his fingers. Sometimes, when about to prepare my own meals, I would open the case in which I kept stored a supply of canned meats and allow Moses to select a can for the purpose. He never failed to pull out one of the cans of beef bearing the blue label. If I put it back, he would again select the same kind, and he could not be deceived in his choice. It was not accidental, because he would hunt until he found the right sort. I don't know what he thought when his choice was not served for dinner. I often exchanged it for another kind without consulting him.

I kept my supply of water in a large jug, which was placed in the shade of the bushes near the cage. I also kept a small pan for Moses to drink out of. He would sometimes ask for water by using his own word for it. He would place his pan by the side of the jug and repeat the sound a few times. If he was not attended to, he proceeded to help himself. He could take the cork out of the jug quite as well as I could. He would then put his eye to the mouth of the vessel and look down into it to see if there was any water. Of course the shadow of his head would darken the interior of the jug so that he could not see anything. Then, removing his eye from the mouth of it, he would poke his hand into it. But I reproved him for this until I broke him of the habit. After a careful examination of the jug he would try to pour the water out. He knew how it ought to be clone, but was not able to handle the vessel. He always placed the pan on the lower side of the jug; then he leaned the jug towards the pan and let go. He would rarely ever get the water into the pan, but always turned the jug with the neck down grade. As a hydraulic engineer he was not a great success, but he certainly knew the first prin ciples of the science.

I tried to teach Moses to be cleanly, but it was a hard task. He would listen to my precepts as if they had made a deep impression, but he would not wash his hands of his own accord. He would permit me or the boy to wash them, but when it came to taking a bath or even wetting his face, he was a rank heretic on the subject, and no amount of logic would convince him that he needed it. When he was given a bath he would scream and fight during the whole process. When it was finished he would climb upon the roof of the cage and spread himself out in the sun. These were the only occasions on which I ever knew him to get upon the roof. I don't know why he disliked the bath so much. He did not mind getting wet in the rain, but rather seemed to like that.

He had a great dislike for ants and certain large bugs. Whenever one such came near him he would talk like a magpie, and brush at the insect with his hands until he got rid of it. He always used a certain sound for this kind of annoyance; it differed slightly from those I have described as warning.

Moses tried to be honest, but he was affected with a species of kleptomania and could not resist the temptation to purloin anything that came in his way. The small stove upon which I prepared my food was placed on a shelf in one corner of the cage, about halfway between the floor and the top. Whenever anything was set on the stove to cook, he had to be watched to keep him from climbing up the side of the cage, reaching his arm through the meshes, and stealing the food. He was sometimes very persevering in this matter. One day I set a tin can of water on the stove to heat, in order to make some coffee. He silently climbed up, reached his hand through, stuck it in the can, and began to search for anything it might contain. I threw out the water, refilled the can, and drove him away. In a few minutes he returned and repeated the act. I had a piece of canvas hung up on the outside of the cage to keep him away. The can of water was placed on the stove for the third time, but within a minute he found his way by climbing up under the curtain, and between that and the cage. I determined to teach him a lesson. He was allowed to explore the can, but finding nothing, he withdrew his hand and sat there clinging to the side of the cage. Again he tried, but found nothing. The water was getting warmer, but was still not hot. At length, for the third or fourth time, he stuck his hand in it up to the wrist. By this time the water was so hot that it scalded his hand. It was not severe enough to do him any harm, but quite enough so for a good lesson. He jerked his hand out with such violence that he threw the cup over and spilt the water all over that side of the cage. From that time to the end of his life he always refused anything that had steam or smoke about it. If anything having steam or smoke was offered him at the table, he would climb down at once and retire from the scene. Poor little Moses ! I knew beforehand what would happen. I did not wish to see him hurt, but nothing else would serve to impress him with the danger and keep him out of mischief.

Anything that he saw me eat he never failed to beg. No matter what he had himself, he wanted to try everything else that he saw me eat. One thing in which these apes appear to be wiser than man is, that when they eat or drink enough to satisfy their wants they quit. Men sometimes do not. Apes never drink water or anything else during their meal, but having finished eating, they want, as a rule, something to drink. The native custom is the same. I have never known the native African to use any kind of diet drink, but always when he has finished eating he takes a draught of water.

Moses knew the use of nearly all the tools that I carried with me in the jungle. He could not use them for the purpose for which they were intended, and I do not know to what extent he appreciated their use; but he knew quite well the manner of using them. I have mentioned the incident of his using the hammer and nails; but he also knew the way to use the saw; however, he always applied the back of it, because the teeth were too rough; but he gave it the motion. When allowed to have it, he would put the back of it across a stick and saw with the energy of a man on a big salary. When given a file, he would file everything that came in his way. If he had applied himself in learning to talk human words as closely and with as much zeal as he tried to use my pliers, he would have succeeded in a very short time.

Whether these creatures are actuated by reason or by instinct in such acts as I have mentioned, the caviller may settle for himself; but the actions accomplish the purpose of the actors in a logical and practical manner, and they are perfectly conscious of the fact.

From the second day after we became associated he appeared to regard me as the one in authority. He would not resent anything I did to him. I could take his food out of his hands, but he would permit no one else to do so. He would follow me and cry after me like a child. As time went by, his attachment grew stronger and stronger. He gave every evidence of pleasure at my attentions, and evinced a certain degree of appreciation and gratitude in return. He would divide any morsel of food with me. This is, perhaps, the highest test of the affection of any animal. I cannot affirm that such an act was genuine benevolence, or an earnest of affection in a true sense of the term; but nothing except deep affection or abject fear impels such actions in animals; and certainly fear was not his motive.

There were others whom he liked and made himself familiar with; there were some that he feared, and others that he hated; but his manner towards me was that of deep affection. It was not alone in return for the food he received, for my boy gave him food more frequently than I did, and many others from time to time fed him. His attachment was like an infatuation that had no apparent motive; it was unselfish and supreme.

The chief purpose of my living among the animals being to study the sounds they utter, I gave strict attention to those made by Moses. For a time it was difficult to detect more than two or three distinct sounds, but as I grew more and more familiar with them I could detect a variety of them, and by constantly watching his actions and associating them with his sounds I learned to interpret certain ones to mean certain things.

In the course of my sojourn with him I learned one sound that he always uttered when he saw anything that he was familiar with, -- such as a man or a dog, -- but he could not tell me which of the two it was. If he saw anything strange to him, he could tell me; but not so that I knew whether it was a snake, or a leopard, or a monkey; yet I knew that it was some strange creature. I learned a certain word for food, hunger, eating, etc., but he could not go into any details about it, except that a certain sound indicated "good" or "satisfaction," and another meant the opposite.

Among the sounds that I learned was one that is used by a chimpanzee in calling another to come to it. Some of the natives assured me that the mothers always use it in calling their young to them. When Moses wandered away from the cage into the jungle, he would sometimes call me with this sound. I cannot express it in letters of the alphabet, nor describe it so as to give a very clear idea of its character. It is a single sound, or word of one syllable, and can be easily imitated by the human voice. At any time that I wanted Moses to come to me I used this word, and the fact that he always obeyed it by coming confirmed my opinion as to its meaning. I do not think that when he addressed it to me he expected me to come to him, but he perhaps wanted to locate me in order to be guided back to the cage by means of the sound. As he grew more familiar with the surrounding forest he used it less frequently, but he always employed it in calling me or the boy. When he was called by it he answered with the same sound; but one fact that we noticed was, that if he could see the one who called he never made any reply. He would obey the call, but not answer. He probably thought that if he could see the one who called he could be seen by him, and it was therefore useless to reply.

The speech of these animals is very limited, but it is sufficient for their purpose. It is none the less real because of its being restricted, but it is more difficult for man to learn, because his modes of thought are so much more ample and distinct. Yet when one is reduced to the necessity of making his wants known in a strange tongue he can express many things in a very few words. I was once thrown among a tribe of whose language I knew less than fifty words, but with little difficulty I succeeded in conversing with them on two or three topics. Much depends upon necessity, and more upon practice. In talking to Moses I used his own language mostly, and was surprised at times to see how readily we understood each other. I could repeat about all the sounds he made except one or two, but I was not able in the time we were together to interpret all of them. These sounds were more than a mere series of grunts or whines, and he never confused them in their meaning. When any one of them was properly delivered to him, he clearly understood and acted upon it.

It had never been any part of my purpose to teach a monkey to talk; but after I became familiar with the qualities and range of the voice of Moses, I determined to see if he might not be taught to speak a few simple words of human speech. To effect this in the easiest way and shortest time, I carefully observed the movements of his lips and vocal organs in order to select such words for him to try as were best adapted to his ability.

I selected the word mamma, which may be considered almost a universal word of human speech; the French word feu, fire; the German word wie, how; and the native Nkami word nkgwe, mother. Every day I took him on my lap and tried to induce him to say one or more of these words. For a long time he made no effort to learn them; but after some weeks of persistent labor and a bribe of corned beef, he began to see dimly what I wanted him to do. The native word quoted is very similar to one of the sounds of his own speech, which means "good'' or "satisfaction." The vowel element differs in them, and he was not able in the time he was under tuition to change them; but he distinguished them from other words.

In his attempt to say mamma he worked his lips without making any sound, although he really tried to do so. I believe that in the course of time he would have succeeded. He observed the movement of my lips and tried to imitate it, but he seemed to think that the lips alone produced the sound. With feu he succeeded fairly well, except that the consonant element, as he uttered it, resembled "v" more than "f," so that the sound was more like vu, making the ''u" short as in "nut." It was quite as nearly perfect as most people of other tongues ever learn to speak the same word in French, and, if it had been uttered in a sentence, any one knowing that language would recognize it as meaning fire. In his efforts to pronounce wie he always gave the vowel element like German "u" with the umlaut, but the "w" element was more like the English than the German sound of that letter.

Taking into consideration the fact that he was only a little more than a year old, and was in training less than three months, his progress was all that could have been desired, and vastly more than had been hoped for. It is my belief that, had he lived until this time, he would have mastered these and other words of human speech to the satisfaction of the most exacting linguist. If he had only learned one word in a whole lifetime, he would have shown at least that the race is capable of being improved and elevated in some degree.

Another experiment that I tried with him was one that I had used before in testing the ability of a monkey to distinguish forms. I cut a round hole in one end of a board and a square hole in the other, and made a block to fit into each one of them. The blocks were then given to him to see if he could fit them into the proper holes. After being shown a few times how to do this, he fitted the blocks in without difficulty-; but when he was not rewarded for the task by receiving a morsel of corned beef or a sardine, he did not attempt it. He did not care to work for the fun alone.

In colors he had but little choice, unless it was something to eat; but he could distinguish them with ease if the shades were pronounced. I had no means of testing his taste for music or sense of musical sounds.

I must here take occasion to mention one incident in the life of Moses, such as perhaps never before occurred in the life of any chimpanzee. While it may not be of scientific value, it is at least amusing.

While living in the jungle I received a letter enclosing a contract to be signed by myself and a witness. Having no means of finding a witness to sign the paper, I called Moses from the bushes, placed him at the table, gave him a pen, and had him sign the document as witness. He did not write his name himself, as he had not mastered the art of writing; but he made his cross mark between the names, as many a good man had done before him. I wrote in the blank the name,

(the cross mark being omitted), and had him with his own hand make the cross as it is legally done by persons who cannot write. With this signature the contract was returned in good faith to stand the test of the law courts of civilization; and thus for the first time in the history of the race a chimpanzee signed his name.

When I prepared to start on a journey across the Esyira country, it was not practicable for me to take Moses along, so I arranged to leave him in charge of a missionary. Shortly after my departure the man was taken with fever, and the chimpanzee was left to the care of a native boy belonging to the mission. The little prisoner was kept confined by a small rope attached to his cage. This was done in order to keep him out of mischief. It was during the dry season, when the dews are heavy and the nights chilly; and the winds at that season are fresh and frequent.

Within a week after I had left him he contracted a severe cold. This soon developed into acute pulmonary troubles of a complex type, and he began to decline. After an absence of three weeks and three days I returned and found him in a condition beyond the reach of treatment. He was emaciated to a living skeleton; his eyes were sunken deep into their orbits, and his steps were feeble and tottering; his voice was hoarse and piping; his appetite was gone, and he was utterly indifferent to everything around him.

During my journey I had secured a companion for him, and when I disembarked from the canoe I hastened to him with this new addition to our little family. I had not been told that he was ill, and, of course, was not prepared to see him looking so ghastly. When he discovered me approaching, he rose up and began to call me, as he had been wont to do before I left him; but his weak voice was like a death-knell to my ears. My heart sunk within me as I saw him trying to reach out his long, bony arms to welcome my return. Poor, faithful Moses! I could not repress the tears of pity and regret at this sudden change, for to me it seemed the work of a moment. I had last seen him in the vigor of a strong and robust youth, but now I beheld him in the decrepitude of a feeble senility. What a transformation

I diagnosed his case as well as I was able and began to treat him, but it was evident that he was so far gone that I could not expect him to recover. My conscience smote me for having left him, yet I felt that I had not done wrong. It was not neglect or cruelty for me to leave him while I went in pursuit of the chief object of my search, and I had no cause to reproach myself for having done so. But emotions that are stirred by such incidents are not to be controlled by reason or hushed by argument, and the pain caused me was more than I can tell.

If I had done wrong, the only restitution possible for me to make was to nurse him patiently and tenderly to the end, or till health and strength should return. This was conscientiously done, and I have the comfort of knowing that the last sad days of his life were soothed by every care that kindness could suggest. Hour after hour during that time he lay silent and content upon my lap. That appeared to be a panacea to all his pains. He would roll up his dark brown eyes and look into my face, as if to be assured that I had been restored to him. With his long fingers he stroked my face as if to say that he was again happy. He took the medicines I gave him as if he knew their purpose and effect. His suffering was not intense, and he bore it like a philosopher. He seemed to have some vague idea of his own condition, but I do not know that he foresaw the result. He lingered on from day to day for a whole week, slowly sinking and growing feebler; but his love for me was manifest to the last, and I dare confess that I returned it with all my heart.

Is it wrong that I should requite such devotion and fidelity with reciprocal emotion? No. I should not deserve the love of any creature if I were indifferent to the love of Moses. That affectionate little creature had lived with me in the dismal shadows of that primeval forest for many long clays and dreary nights; had romped and played with me when far away from the pleasures of home; and had been a constant friend, alike through sunshine and storm. To say that I did not love him would be to confess myself an ingrate and unworthy of my race.

The last spark of life passed away in the night. Death was not attended by acute pain or struggling; but, falling into a deep and quiet sleep, he woke no more.

Moses will live in history. He deserves to do so, because he was the first of his race that ever spoke a word of human speech; because he was the first that ever conversed in his own language with a human being; and because he was the first that ever signed his name to any document. Fame will not deny him a niche in her temple among the heroes who have led the races of the world.

About the time I reached the trading post, two Esyira hunters arrived from a distant village and brought with them a smart young chimpanzee of the kind known in that country as the kulu-kamba. He was quite the finest specimen of his race that I have ever seen. His frank, open countenance, big brown eyes, and shapely physique, free from mark or blemish of any kind, would attract the notice of any one not absolutely stupid. It is not derogatory to the memory of Moses that I should say this, nor does it lessen my affection for him. Our passions are not moved by visible forces nor measured by fixed units. They disdain all laws of logic, spurn the narrow bounds of reason, and conform to no theory of action.

As soon as I saw this little ape I expressed a desire to own him. So the trader in charge bought him and presented him to me. As it had been intended that he should be the friend and ally of Moses, although not his brother, I conferred upon him the name of Aaron. The two names are so intimately associated in history that the mention of one always suggests the other.

Aaron was captured in the Esyira jungle by the hunters, about one day's journey from the place where I secured him; and with this event began a series of sad scenes in the brief but varied life of this little hero such as seldom come within the experience of any creature.

At the time of his capture his mother was killed in the act of defending him from the cruel hunters. When she fell to the earth, mortally wounded, this brave little fellow stood by her trembling body defending it against her slayers, until he was overcome by superior force, seized by his captors, bound with strips of bark, and carried away into captivity. No human can refrain from admiring his conduct in this act, whether it was prompted by the instinct of self-preservation or by a sentiment of loyalty to his mother, for he was exercising that prime law of nature which actuates all creatures to defend themselves against attack, and his wild, young heart throbbed with sensations like to those of a human under similar ordeal.

I do not wish to appear sentimental by offering a rebuke to those who indulge in the sport of hunting; but much cruelty could be obviated without losing any of the pleasure of the hunt. I have always made it a rule to spare the mother with her young. Whether or not animals feel the same degree of mental and physical pain as man, they do, in these tragic moments, evince for one another a certain amount of concern. This imparts a tinge of sympathy that must appeal to any one who is not devoid of every sense of mercy. It is true that it is often difficult and sometimes impossible to secure the young by other means; but the manner of getting them often mars the pleasure of having them; and while Aaron was to me a charming pet and a valuable subject for study, I confess the story of his capture always touched me in a tender spot.

I may here mention that the few chimpanzees that reach the civilized parts of the world are but a small percentage of the great number that are captured. Some die on their way to the coast, others die after reaching it, and scores of them die on board the ships to which they have been consigned for various ports of Europe and other countries. Death results not often from neglect or cruelty, but usually from a change of food, climate, or condition; yet the creature suffers just the same whether the cause is from design or accident. One fruitful source of death among them is pulmonary trouble of various types.

One look at the portrait of Aaron will impress any one with the high mental qualities of this little captive; but to see and study them in life would convince a heretic of his superior character. In every look and gesture there was a touch of the human that no one could fail to observe. The range of facial expression surpassed that of any other animal I have ever studied. In repose his quaint face wore a look of wisdom becoming to a sage; while in play it was crowned with a grin of genuine mirth. The deep, searching look he gave to a stranger was a study for the psychologist. The serious, earnest look of inquiry when he was perplexed would have amused a stoic. All these changing moods were depicted in his mobile face with such intensity as to leave no room to doubt the activity of certain faculties of the mind to a degree far beyond that of animals in general; and his conduct in many instances showed the exercise of mental powers of a higher order than that limited agency known as instinct. In addition to these facts, his voice was of better quality and more flexible than that of any other specimen I have ever known. It was clear and smooth in uttering sounds of any pitch within its scope, while the voices of most of them are inclined to be harsh or husky, especially in sounds of high pitch.

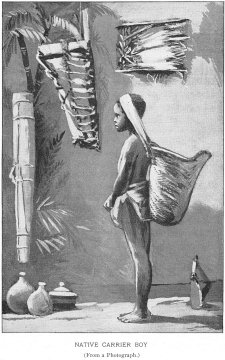

Before leaving the village where I secured him, I made a kind of sling for him to be carried in. It consisted of a short canvas sack, having two holes cut in the bottom for his legs to pass through. To the top of this was attached a broad band of the same cloth by which to hang it over the head of the carrier boy to whom the little prisoner was consigned. This afforded the ape a comfortable seat, and at the same time reduced the labor of carrying him. It left his arms and legs free, so he could change his position and rest, while it also allowed the boy the use of his own hands in passing any difficult place in the jungle along the way.

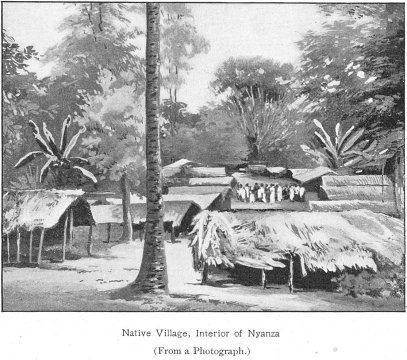

From the trading post to the Rembo was a journey of five days on foot. Along the way were a few straggling villages; but most of the route lay through a wild and desolate forest, traversed by low, broad marshes, through which wind shallow sloughs of filthy, greenish water, seeking its way among bending roots and fallen leaves. From the foul bosom of these marshes rise the effluvia of decaying plants, breeding pestilence and death. Here and there across the dreary tracts is found the trail of elephants, where the great beasts have broken their tortuous way through the dense barriers of bush and vine. These trails serve as roads for the native traveler and afford the only way of crossing these otherwise trackless jungles. The only means of passing the dismal swamps is to wade through the thin, slimy mud, often more than knee-deep, and sometimes extending many hundred feet in width. The traveler is intercepted at almost every step by the tangled roots of mangrove trees under foot or clusters of vines hanging from the boughs overhead.

Such was the route we came. But Aaron did not realize how severe was the task of his carrier in trudging his way through such places, and the little rogue often added to the labor by seizing hold of limbs or vines that hung within his reach in passing. Thus he retarded the progress of the boy, who strongly protested against the ape's amusing himself in this manner. The latter seemed to know of no reason why he should not do so, and the former did not deign to give one. So the quarrel went on until we reached the river; but by that time each of them had imbibed a hatred for the other that nothing in the future ever allayed.

Neither of them ever forgot it while they were associated, and both of them evinced their aversion on all occasions. The boy gave vent to his dislike by making ugly faces at the ape, and the latter showed his resentment by screaming and trying to bite him. Aaron refused to eat any food given him by the boy, and the boy would not give him a morsel except when required to do so. At times the feud became ridiculous. It ended only with their final separation. The last time I ever saw the boy, I asked him if he wanted to go with me to my country to take care of Aaron; but he shook his head and said: "He's a bad man." This was the only person for whom I ever knew Aaron to conceive a deep and bitter dislike, but the boy he hated with his whole heart.

On my return to Ferran Vaz, where I had left Moses, I found him in a feeble state of health, as related elsewhere. When Aaron was set clown before him, he merely gave the little stranger a casual glance, but held out his long, lean arms for me to take him in mine. His wish was gratified, and I indulged him in a long stroll. When we returned I set him down by the side of his new friend, who evinced every sign of pleasure and interest. He was like a small boy when there is a new baby in the house. He cuddled up close to Moses and made many overtures to become friends; but, while the latter did not repel them, he treated them with indifference. Aaron tried in many ways to attract the attention of Moses, or to elicit from him some sign of approval, but it was in vain.

No doubt Moses' manners were due to his sickness, and Aaron seemed to realize it. He sat for a long time holding a banana in his hand and looking with evident concern into the face of his little sick cousin. At length he lifted the fruit to the lips of the invalid and uttered a low sound; but the kindness was not accepted. The act was purely one of his own volition, to which he was not prompted by any suggestion from others. Every look and motion indicated a desire to relieve or comfort his friend. His manner was gentle and humane, and his face was an image of pity.

Failing to get any sign of attention from Moses, Aaron moved up closer to his side and put his arms around him in the manner that is shown in the picture of him with Elisheba. During the days that followed, he sat hour after hour in the same attitude, and refused to allow any one except myself to touch his patient; but on my approach he always resigned him to me, while he watched with interest to see what I did for him.

Among other things, I gave Moses twice a day a tabloid of quinine and iron. This was dissolved in a little water and given to him in a small tin cup kept for the purpose. When not in use, the cup was hung upon a tall post. Aaron soon learned to know the use of it, and whenever I went to Moses, Aaron would climb up the post and bring me the cup to administer the medicine. It is not to be inferred that he knew anything about the nature or effect of the medicine, but he knew the use, and the only use, to which that cup was put.

Aaron displayed a marked interest during the act of administering the dose, and seemed to realize that it was intended for the good of the patient. He would sit close up to one side of the sick one and watch every movement of his face, as if to see what effect was being produced, while the changing expressions of his own visage plainly showed that he was not indifferent to the actions of the patient.

While I was present with the sick one, Aaron appeared to feel a certain sense of relief from the care of him, and frequently went climbing about as if to rest and recreate himself by a change of routine. Whenever I took Moses for a walk, or sat with him on my lap, his little nurse was perfectly content; but the instant they were left alone, Aaron would again fold him in his arms, as if he felt it a duty to do so.

It was only natural that Moses, in such a state of health, should be cross and peevish at times, as human beings in a like condition are; but I never once saw Aaron resent anything Moses did, or display the least ill-temper towards him. On the contrary, his conduct was so patient and forbearing that it was hard to forego the belief that it was prompted by the same motives of kindness and sympathy that move the human heart to deeds of tenderness and mercy. At night, when they were put to rest, they lay cuddled up in each other's arms, and in the morning they were always found in the same close embrace.

But on the morning Moses died the conduct of Aaron was unlike anything I had observed before. When I approached their snug little house and drew aside the curtain, I found him sitting in one corner of the cage. His face wore a look of concern, as if he were aware that something awful had occurred. When I opened the door he neither moved nor uttered any sound. I do not know whether or not apes have any name for death, but they surely know what it is.

Moses was dead. His cold body lay in its usual place; but it was entirely covered over with the piece of canvas kept in the cage for bed-clothing. I do not know whether or not Aaron had covered him up, but he seemed to realize the situation. I took him by the hand and lifted him out of the cage, but he was reluctant. I had the body removed and placed on a bench about thirty feet away, in order to dissect it and prepare the skin and the skeleton for preservation.

When I proceeded to do this, I had Aaron confined to the cage, lest he should annoy and hinder me at the work; but he cried and fretted until he was released. It is not meant that he shed tears over the loss of his companion, for the lachrymal glands and ducts are not developed in these apes; but they manifest concern and regret, which are motives of the passion of sorrow. But being left alone was the cause of Aaron's sorrow. When released he came and took his seat near the dead body, where he sat the whole clay long and watched the operation.

After this Aaron was never quiet for a moment if he could see or hear me, until I secured another of his kind as a companion for him; then his interest in me abated in a measure, but his affection for me remained intact. His conduct towards Moses always impressed me with the belief that he appreciated the fact that the sick one was in distress or pain, and while he may not have foreseen the result, when he saw death he certainly knew what it was. Whether it is instinct or reason that causes man to shrink from death, the same influence works to the same end in the ape; and the demeanor of this ape towards his later companion, Elisheba, only confirmed this opinion.

Our progress was slow and the journey tedious. The only passage out of the lake at that season is through a long, narrow, winding creek beset by sand bars, rocks, logs, and snags, and in some places overhung by low, bending trees. But the wild, weird scenery is grand and beautiful. Long lines of bamboo, broken here and there by groups of pendanus or stately palms; islands of lilies, and long sweeps of papyrus spreading away from the banks on either side; the gorgeous foliage of aquatic plants, drooping along the margin like a massive fringe and relieved by clumps of tall, waving grass, forms a perfect Eden for the birds and the monkeys that dwell among those scenes of eternal summer.

After a delay of eight days at Cape Lopez, we secured passage on a small French gunboat called the Komo, by which we came to Gaboon. There I found another kulu-kamba. She was in the hands of a generous friend, Mr. Adolph Strohm, who presented her to me. I gave her to Aaron as a wife and called her Elisheba, -- after the name of the wife of the great high-priest. Elisheba had been captured on the head-waters of the Nguni River, in about the same latitude that Aaron was found in, but more than a hundred miles to the east of that point and a few minutes north of it. I did not learn the history of her capture.

It would be difficult to find any two human beings more unlike in taste and temperament than these two apes were. Aaron was one of the most amiable of creatures; he was affectionate and faithful to those who treated him kindly; he was merry and playful by nature, and often evinced a marked sense of humor; he was fond of human society and strongly averse to solitude or confinement.

Elisheba was a perfect shrew. She often reminded me of certain women that I have seen who had soured on the world. She was treacherous, ungrateful, and cruel in every thought and act; she was utterly devoid of affection; she was selfish, sullen, and morose at all times; she was often vicious and always obstinate; she was indifferent to caresses, and quite as well content when alone as in the best of company. It is true that she was in poor health, and had been badly treated before she fell into my hands; but she was by nature endowed with a bad temper and depraved instincts.

It is not at all rare to see a vast difference of manners, intelligence, and temperament among specimens that belong to one species. In these respects they vary as much in proportion to their mental scope as human beings do; but I have never seen, in any two apes of the same species, the two extremes so widely removed from one another.

While waiting at Gaboon for a steamer I had my own cage erected for the apes to live in, as it was large and gave them ample room for play and exercise. In one corner of it was suspended a small, cosy house for them to sleep in. It was furnished with a good supply of clean straw and some pieces of canvas for bedclothes. In the center of the cage was a swing, or trapeze, for them to use at their pleasure. Aaron found this a means of amusement, and often indulged in a series of gymnastics that might evoke the envy of a king of athletic sports.

Elisheba had no taste for such pastime, but her depravity could never resist the impulse to interrupt Aaron in his jolly exercise. She would climb up and contend for possession of the swing, until she would drive him away. Then she would perch herself on it and sit there for a time in stolid content; but she would neither swing nor play. Frequently during the day, when Aaron was lying quietly on the straw, she would go into the snug little house and raise a row with him by pulling the straw from under him, a handful at a time, and throwing it out of the box till there was none left in it. No matter what kind or quantity of food was given them, she always wanted the piece he had, and would fuss with him to get it; but having got it, she would sit holding it in her hand without eating it; for there were some things that he liked which she would not eat at all.

When we went out for a walk, no matter which way we started, Elisheba always contended to go some other way. If I yielded, she would again change her mind and start off in some other direction. If forced to submit, she would scream and struggle as if for life. I cannot forego the belief that these freaks were due to a base and perverse nature, and I could find no higher motive in her stubborn conduct.

Aaron was very fond of her and rarely ever opposed her inflexible will. He clung to her and let her lead the way. I have often felt vexed at him because he complied so readily with her wishes. The only case in which he took sides against her was in her conduct towards me.

When I first secured her she had the temper of a demon, and with the smallest pretext she would assault me and try to bite me or tear my clothes. In these attacks Aaron was always with me, and the loyal little champion would fly at her in the greatest fury. He would strike her over the head and back with his hands, and bite her and flog her till she desisted. If she returned the blow he would grasp her hand and bite it, or strike her in the face. He would continue to fight till she submitted. Then he would celebrate his victory by jumping up and down in a most grotesque fashion, stamping his feet, slapping his hands on the ground, and grinning like a mask. He seemed as conscious of what he had done and as proud of it as any human could have been; but no matter what she did to others, he was always on her side of the question. If any one else annoyed her, he would always resent it with violence.

About the premises there were natives all the time passing to and fro, and these two little captives were objects of special interest to them. They would stand by the cage hour after hour and watch them. The ruling impulse of nearly all natives appears to be cruelty, and they cannot resist the temptation to tease and torture anything that is not able to retaliate. They were so persistent in poking sticks at my chimpanzees that I had to keep a boy on watch all the time to prevent it; but the boy could not be trusted, so I had to watch him.

In the rear of the room that I occupied was a window through which, from time to time, I watched the boy and the natives, and when anything went wrong I would call out to the boy. Aaron soon observed this and found that he could get my attention himself by calling out when any one annoyed him, and he also knew that the boy was put there as a protector. Whenever any of the natives came about the cage he would call for me in his peculiar manner, which I well understood and promptly responded to. The boy also knew what the call meant and would rush to the rescue. If I were away from the house and the boy were aware of the fact, he was apt to be tardy in coming to the relief of the ape, and sometimes he did not come at all. In the latter event the two would crawl into their house and pull down the curtain so that they could not be seen. Here they would remain until the natives had left or some one came to their aid.

Neither of the apes ever resented anything the natives did to them, unless they could see me about; but whenever I came in sight they would make battle with their tormentors, and, if liberated from the big cage, they would chase the last one of them out of the yard. Aaron knew perfectly well that they were not allowed to molest him or his companion; and when he knew that he had my support he was ready to carry on the war to a finish. But it was really funny to see how meek and patient he was when left to defend himself alone against the native with a stick, and then to note the change in him when he knew that he was backed up by a friend upon whom he could rely.

Mr. Strohm, the trader, previously mentioned, with whom I found hospitality at this place, kept a cow in the lot where the cage was. She was a small black animal, the first cow that Aaron had ever seen. He never ceased to contemplate her with wonder and with fear. If she came near the cage when no one was about, he hurried into his box and from there peeped out in silence until she went away. The cow was equally amazed at the cage and its strange occupants, though she was less afraid than they, and frequently came near to inspect them. She would stand a few yards away with her head lifted high, her eyes arched and her ears thrown forward, waiting for them to come out of that mysterious box. But they would not venture out of their asylum while she remained. At last, tired of waiting, she would switch her tail, shake her head, and turn away.

When taken out of the cage Aaron had special delight in driving the cow away; and if she was around he would grasp me by the hand and start towards her. He would stamp the ground with his foot, strike with all force with his long arm, slap the ground with his hand, and scream at her at the top of his voice. If she moved away, he would let go my hand and rush towards her as though he intended to tear her up; but if the cow turned suddenly towards him, the little fraud would run to me, grasp my leg, and scream with fright. The cow was afraid of a man, and as long as she was followed by one she would continue to go; but when she discovered the ape to be alone in the pursuit, she would turn and look as if trying to determine what manner of thing it was. Elisheba never seemed to take any special notice of the cow except when she approached too near the cage, and then it was due to the conduct of Aaron that she made any fuss about it.

On board the steamer in which we sailed for home there was a young elephant that had been sent by a trader, for sale. He was kept on deck in a strong stall built for his quarters. There were wide cracks between the boards, and the elephant had the habit of reaching his trunk through them in search of anything he might find. With his long, flexible proboscis extended, he would twist and coil it in all manner of writhing forms. This was the crowning terror of the lives of those two apes; it was the bogie-man of their existence, and nothing could induce either of them to go near it. If they saw me approach it, they would scream and yell until I came away. If Aaron could get hold of me without getting too near the elephant, he clung to me until he almost tore my clothes, to keep me away from it. It was the one thing that Elisheba was afraid of, and the only one against which she ever gave me warning.

They did not manifest the same concern for others, but sat watching them without offering any protest. Even the stowaway who fed them and attended to their cage was permitted to approach the elephant; but their solicitude for me was remarked by every man on board. I was never able to tell what their opinion of the thing was. They were much less afraid of the elephant when they could see all of him, than they were of the trunk when they saw that alone. They may have thought the latter to be a big snake; but this is only a conjecture.

At the beginning of the voyage I took six panels of my own cage and made a small cage for them. I taught them to drink water from a beer bottle with a long neck that could be put through a mesh of the wires. They preferred this mode of drinking and appeared to look upon it as an advanced idea. Elisheba always insisted on being served first; being a female, her wish was complied with. When she had finished, Aaron would climb up by the wires and take his turn. There is a certain sound, or word, which the chimpanzee always uses to express "good" or "satisfaction," and he made frequent use of it. He would drink a few swallows of the water and then utter the sound, whereupon Elisheba would climb up again and taste. She seemed to think it something better than she was drinking, but finding it the same as she had had, she would again give way for him. Every time he used the sound she would take another taste and turn away; but she never failed to try it if he uttered the sound.

The boy who cared for them on the voyage was disposed to play tricks on them. One of these ugly pranks was to turn the bottle up so that when they had finished drinking and took their lips away, the water would spill out and run down over them. Several times they declined to drink from the bottle while he was holding it, but when he let it go, it hung in such a position that they could not get the water out of it at all. At length Aaron solved the problem by climbing up one side of the cage and getting on a level with the bottle; then he reached across the angle formed by the two sides of the cage and drank. In this position it was no matter to him how much the water ran out; it couldn't touch him. Elisheba watched him until she quite grasped the idea; then she climbed up in the same manner and slaked her thirst. I scolded the boy for serving them with such cruel tricks; but it taught me another lesson of value concerning the mental resources of the chimpanzee, for no philosopher could have found a much better scheme to obviate the trouble than did this cunning little sage in the hour of necessity.

I have never regarded the training of animals as the true measure of their mental powers. The real test is to reduce the animal to his own resources, and see how he will conduct himself under conditions that present new problems. Animals may be taught to do many things in a mechanical way, and without any motive that relates to the action; but when they can work out the solution without the aid of man, it is only the faculty of reason that can guide them.

One thing that Aaron could never figure out was -- what became of the chimpanzee that he saw in a mirror. I have seen him hunt for that mysterious ape an hour at a time. He once broke a piece off a mirror I had in trying to find the other fellow, but he never succeeded. I have held the glass firmly before him, while he put his face up close to it -- sometimes almost in contact. He would quietly gaze at the image and then reach his hand around the glass to feel for it. Not finding it, he would peep around the side of the glass and then look into it again. He would take hold of it and turn it around, lay it on the ground, look at the image again, and put his haul under the edge of the glass. The look of inquiry in that quaint face was so striking as to make one pity him. But he was hard to discourage. He resumed the search whenever he had the mirror.

Elisheba never worried herself much about it. When she saw the image in the glass she seemed to recognize it as one of her kind; but when it vanished she let it go without trying to find it. In fact, she often turned away from it as though she did not admire it. She rarely ever took hold of the glass, and she never felt behind it for the other ape.

Altogether Elisheba was an odd specimen of her tribe -- eccentric and whimsical beyond anything I have ever known among animals; yet, with all her freaks, Aaron was fond of her and she afforded him company; but he was extremely jealous of her, and permitted no stranger to take any liberties with her with impunity. He did not object to their doing so with him. He rarely took offense at any degree of familiarity, for he would make friends with any one who was gentle with him; but he could not tolerate their attentions to her. She betrayed no sign of affection for him except when some one annoyed or vexed him; but in that event she never failed to take his part against all odds. At such times she became frantic with rage, and if the cause was prolonged, she often for hours afterwards refused to eat.

On the voyage homeward there was on board another chimpanzee, belonging to a sailor who was bringing him home for sale. This one was about two years older than Aaron and fully twice as large. He was tame and gentle, but was kept in a close cage by himself. He saw the others roaming about the deck and tried to make up with them; but they evinced no desire to become intimate with one who was confined in such a manner.

One bright Sunday morning, as we rode the calm waters near the Canary Islands, I induced the sailor to release his prisoner on the main deck with my own, to see how they would act towards each other. He did so, and in a moment the big ape came ambling along the deck towards Aaron and Elisheba, who were sitting on the top of a hatch, absorbed in gnawing some turkey bones.

As the stranger came near he slackened his pace and gazed earnestly at the others. Aaron ceased eating and stared at the visitor with a look of surprise, but Elisheba barely noticed him. He scanned Aaron from head to foot, and Aaron did the same with him. He advanced until his nose almost touched that of Aaron, and in this position the two remained for some seconds. Then the big one proceeded to salute Elisheba in the same manner, but she gave him little attention. She continued to gnaw the bone in her hand, and he had no reason to feel flattered at the impression he appeared to have made on her. Aaron watched him with deep concern, but without uttering a sound.

Turning again to Aaron, the big ape reached out for his turkey bone; but the hospitality of the little host was not equal to the demand. He drew back with a shrug of his shoulder, holding the bone closer to himself, and then he resumed eating. Then a steward gave a bone to the visitor. He climbed upon the hatch and took a seat on the right of Elisheba, Aaron being seated at her left. As soon as the big one had taken his seat, Aaron resigned his place and crowded himself in between them. The three sat for a few moments in this order, till the big one got up and deliberately walked around to the other side of Elisheba and sat down again beside her. Again Aaron forced himself in between them.

This act was repeated six or eight times; then Elisheba left the hatch and took a seat on a spar that lay on deck. The big ape immediately moved over and sat down near her; but by the time he was seated Aaron again got in between them, and as he did so he struck his rival a smart blow on the back. They sat in this manner for a minute or so. Then Aaron drew back his hand and struck again. He continued his blows, all the while increasing them in force and frequency; but the other did not resent them. His manner was one of dignified contempt, as if he regarded the inferior strength of his assailant unworthy of his own prowess. It would be absurd to suppose that he was constrained by any principle of honor, but his demeanor was patronizing and forbearing, like that of a considerate man towards a small boy.

One amusing feature of the affair was the half-serious and half-jocular manner of Aaron. When striking, he did not turn his face to look at his rival, and the instant the blow was delivered he withdrew his hand as if to avoid being detected. He gave no sign of anger though he made no effort to conceal his jealousy; and the other seemed to be aware of the cause of his disquietude. The smirk of indifference on the little lover's face belied the state of mind that impelled his action, and it was patent to all who witnessed the tilt that Aaron was jealous of his guest. From time to time Elisheba would change her seat. Then a similar scene would ensue.

The whole affair was so comical and yet so real that one could not repress the laughter it evoked. It was the drama of "love's young dream" in real life, in which every man, at some period of his young career, has played each part the same as these two rivals played. Every detail of plot and line was the duplicate of a like incident in the experience of boyhood.

Elisheba did not seem to encourage the suit of this simian beau, but she did not rebuff him as a true and faithful spouse should do, and I never blamed Aaron for not liking it. She had no right to tolerate the attentions of a total stranger; but she was feminine, and, perhaps, endowed with all the vanity of her sex, and fond of adulation. However, my sympathies for the devoted little Aaron were too strong for me to permit him to be imposed upon by a rival twice as big and three times as strong as himself; so I took him and Elisheba away to the after deck, where they had a good time alone.