Volume 1813b

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the

advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/buel2a.htm

Heroes of the Dark Continent . . .

J.W. Buel

PART IIa: Chapters XXVI - XXX1 and Appendix &

Epilogue

CONTINUED FROM

PART II

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Chapter XXVI. |

Adventures on the Route - Stanley's studies of the natives - Cruel

devices of the natives - Wounded in the feet by concealed skewers - Insects

that make life on the Congo unbearable - Mists of the morning - Poisoned

arrows - How the poison is made - Agriculture on the Congo - Exciting sport

on the Aruwimi - Hippopotami, monkeys and crocodiles - Mohammedans eating

hippopotami flesh under a dispensation - A hippopotamus adventure - Lieut.

Stairs in danger - Attacked by a wounded hippopotamus - Stanley to the

rescue - Among the crocodiles - The snake-eaters - How the crocodile is

hunted - Crocodile traps - The Wambutti dwarfs - Some fearful stories -

Appearance and customs of the dwarfs - Cannibalism - Affection exhibited

by a bereaved mother - Disposition of the Dwarfs' dead - The Quimbandes

- Habits and appearance - A tribe with tails - Scared by a camera - Singular

tribes - The M'teita tribe - Their customs and hospitality. |

| Chapter XXVII. |

The Approach to Albert Lake - A scramble for a sardine box - Weakened

by hunger - "Cheer up, boys!" - A park-like country - Purpose of the Maxim

gun - A big hunt - Charge of a mad buffalo - Look out for the rhinoceros!

- A dash through the carriers - A dreadfully scared company - A bath in

the lake - Return to the Aruwimi camp - Deplorable condition of the rear

column - Small-pox and other sufferings - Relief after a long siege of

starvation - A capture of Dwaris natives - Again on the brink of starvation

- Calling a council - Search for the missing - Letters from Jephson - Jephson

and Emin prisoners of the Mahdi - The victorious Mahdi - The situation

very serious - Release of Emin, but sad forebodings - Stanley's reply to

Jephson - Fascinated by the Soudan - Stanley's warnings - Arrival of Jephson

- A courier from Emin. |

| Chapter XXVIII. |

Discoveries which Excite the World's Applause - Stanley's feeling towards

Emin - Rehearsing the perils of his march - The Mayuemas and the slave

traders - Wonderful discoveries - The Ruewenzori snowy range - Salt lakes

- A geographical review - Correcting mistakes of the former explorers -

Extent of Albert Lake - Views about Albert Lake and Mt. Ruewenzori - Mistakes

of Baker - New sources of the Nile - Disappointments crowd fast on one

another - Dangerous position of Jephson and Emin - Invasion of the Mahdists

- Indecision of Emin - A lion hunt - Scarcity of lions in West Africa -

The game located - A night station in a tree - Approach of three lions

- A magnificent moonlight scene - Two lions wounded - Twenty shots required

to bag the game - A savage struggle with death - Carrying a lion's head

as a trophy. |

| Chapter XXIX. |

A Great Hunt - Shooting hippopotami on Albert Lake - An elephant hunt

- A terrifying spectacle - A vast sea of grass - Flanking the herd - Stanley

selects a great tusker - Retreat of the wounded elephant - The pursuit

- Another shot - Furious charge of the elephant - Narrow escape of Stanley

- Death of the monarch - Vast elephant herds in the Congo region - Tipo

Tib's vast stores of ivory - Value of the ivory annually collected - 200,000

elephants - Other rich products - Preparing to return to Zanzibar - Vigorous

measures for suppressing a conspiracy - Number and kinds of people composing

the returning caravan. |

| Chapter XXX. |

The March to the Sea - Justice to Emin - A letter from Emin - Another

letter from Stanley - The lofty Ruewenzori range - A fight - A delusion

- A brush with the Warasura - Scaling the mountain - A vast sea of salt

- The caravan stricken with fever - A land desolated by pillage - A tradition

of the Snow King - Fields of rich promise - Descriptions of the tribes

- Remarkable vicissitudes. |

| Chapter XXXI. |

End of the Journey - The return route - Expert tree - climbers - Why

they made their habitations in trees - Shooting an eagle by magic - A funny

scene - A singular annual custom - The Wahuma chief and his wives - Incidents

of the march - Dying on the way - An accident from exploding shells - Enraged

natives - Emin Pasha's daughter - A Hebrew turned Mohammedan - News of

Stanley's return - Dying in hammocks - Evil reports - A meeting between

Stanley and Wissmann - The mirth that a snake produced - Jephson's wild

ride - Arrival at Bagamoyo - Magnificent reception accorded the explorers

- A champagne banquet - An accident to Emin Pasha - His fall from a high

balcony and dangerous hurt - Honors to Stanley - Banqueted, toasted and

feted by distinguished people - Honored by the Khedive - His visit to Cairo. |

| APPENDIX. |

|

| ADDENDA --- AN EPILOGUE. |

|

ADVENTURES ON THE ROUTE.

The description which Stanley gives of his journey from Yambuya to Kavalli,

on Lake Albert, is in the nature of a report to a scientific body, and

therefore, while reciting the perils of the march, it does not descend

to the particulars of adventures, which he reserved for subsequent description,

for publication as well as to add exciting interest to the letters which

he wrote from Africa to his friends. It was my good fortune to be able

to secure facts from his correspondence, and to add here the principal

adventures of his most memorable journey.

As an explorer, whose chief mission, while philanthropic, was hardly

less an ambition to familiarize himself with new regions, Stanley could

not afford to disregard even the traditions respecting the country lying

along the Aruwimi river, especially since, though possibly idle stories,

they were evidently grounded firmly in the beliefs of both Arabs and natives

of all Central Africa. By this careful attention to beliefs, as well as

critical observation, he has been able to give us much information about

tribes which have never before been brought to the notice of even ethnologists,

much less to the great mass of people. To features of his march not described

in his letter to the Relief Committee we must therefore now address ourselves.

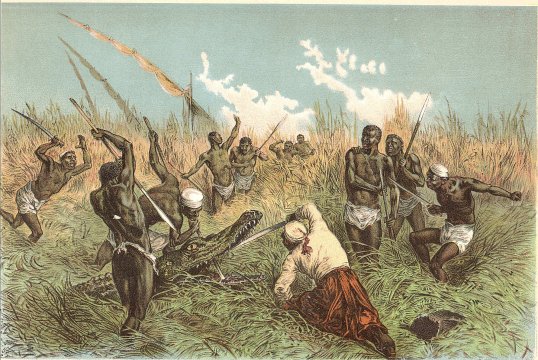

[Mustering

of the hostiles]

CRUEL DEVICES ADOPTED BY THE NATIVES.

Among other difficulties encountered on the journey, Stanley says that

very shortly after the expedition departed from Yambuya the members were

initiated into the subtleties of savage warfare. Among other arts practised

by the natives for annoying strangers was that of filling shallow pits

with sharpened splinters, or skewers, deftly covered over with leaves.

For barefooted people the results were terrible; and ten men were wounded

by these skewers, which would often perforate the foot quite through, or

the tops would be buried in the feet, producing gangrenous sores.

To these distressful annoyances, or more properly murderous obstructions,

complaint is added against swarming insects, such as gnats, flies and ants,

which, in some places attacked the expedition in such numbers and with

such venomous bites as forced the men to throw down their burdens and fight

for life. [Dwellings

of tribes below Nejambi Rapids.]

The mornings along the river were generally lowering and very sombre,

everything being buried in thick mist, which frequently did not clear off

until nearly noon. While this lasted the air was still as death, and gave

the insects opportunity for foraging off every living thing. When the sun

came out, and the breeze sprang up, the small winged creatures fled away

and settled.

The Nejambi Rapids marked the division between two different kinds of

architecture and language. Below were the cone huts; above were villages

long and straight, of detached square huts surrounded by tall logs of wood,

which added materially to the strength of the village. But all the villages

were hostile, and were also armed with strong bows from which poisoned

arrows were discharged with deadly effect. Stanley and his officers became

much exercised as to what might be the poison on the heads of the arrows

by which Lieutenant Stairs and several others were wounded, and from the

effects of which four died almost directly. During a halt at Avesibba several

packets of dried red-ants were found, and the secret was out. The bodies

of these insects were dried, ground into powder, cooked in palm oil, and

smeared on the arrow tips, and thus the deadly irritant, by which so many

men had been lost after the most terrible suffering, was conveyed into

the arrow wounds. This poison is so potent that it is forbidden to prepare

it near a village. [ELEVATED

DWELLINGS ALONG THE ARUWIMI.]

Stanley also mentions having seen immense piles of oyster shells on

several islands in the Aruwimi, though this peculiar species of bivalves

is not now found living in the river. He also notes a curious means employed

by the natives in clearing the forests of tall white-stemmed trees characteristic

of the Lower Congo, which is by building a platform about the trees, ten,

fifteen, and even twenty feet high, and then cutting off the trunk at that

height. The purpose of this most singular practice could not be discovered,

except that the natives considered too much labor involved in the clearing

out of trunks and stumps, and therefore thought all useful means were accomplished

by the lopping off of that portion of the tree whose foliage would give

too much shade to what they planted. Nor is this theory without reason,

for in Africa land has no ownership, and the tribes are usually migratory.

A single, or at most two crops are harvested by one family on the same

ground in many districts, hence a thorough clearing cannot be afforded.

Stanley also incidentally notes having seen occasional huts built on piles,

and even stumps of trees, at a considerable elevation, but does not give

us the reasons for this kind of architecture.

EXCITING SPORT ON THE ARUWIMI.

While a much larger part of the journey toward Kavalli was made on land,

along the river shore, yet in several instances large canoes, called nuggers,

were procurable at native villages, and in these the expedition travelled

until an interruption in the navigation compelled a return to the land.

Canoes were always hard to obtain, and in nearly all cases where they could

be hired the owners would not allow them to be taken beyond a few miles.

It is true, Stanley had a sufficiently well-armed force with him to take

by violence what he was unable to secure by purchase, but his was a peaceful

mission, and he avoided, even to the point of seeming cowardice, collisions

with the natives, in no instance beginning an attack, and always resorting

to every possible means for evading a fight even in his own defence. Notwithstanding

his sufferance, however, he was forced many times to make a vigorous defence

to avoid destruction at the hands of violently hostile tribes who opposed

every conceivable impediment at their command to his advance. [A

SCHOOL OF HIPPOPOTAMI.]

The short relays of canoes that were obtainable gave great relief to

the weary and footsore travellers, besides often affording exciting sport

to the hunters and venturously inclined members of the expedition. The

river has little current, on which account, as well as the few disturbances

of the ancient quiet of that region, it is made the haunt of great numbers

of hippopotami and crocodiles, while monkeys of many varieties are to be

constantly seen in wanton gambols among the trees that line the banks.

Being well supplied with arms and ammunition, Stanley and his lieutenants

found much amusement shooting the larger game from the canoes; and even

their Arab auxiliaries, who generally maintained a melancholy mien, threw

off their sullenness for an occasional hunt along the shores.

Many times during the trip the party were sorely pressed for food, and

were forced to many expedients to obtain it. The natives were generally

very poor themselves, and while having little to sell, were even less inclined

to furnish food for strangers. Hunting, too, was frequently a doubtful

resource, because, while in certain sections game was abundant, in others

there seemed to be no animal life whatever. The Arabs -- ; about

a dozen having followed the expedition after Tipo Tib left it at Stanley

Falls -- ; fared worse than the others, because of their religious

scruples about eating hippopotamus flesh, which they regard as unclean.

But the gnawing pangs of hunger finally overcame the proscription of creed

and belief, so that they were brought to partake of the forbidden food.

It was a ludicrous sight to Christians to see a lay Mohammedan acting the

part of priest and blessing the dead body of a hippopotamus preparatory

to making a feast, and in the ceremony to see so strong a religious barrier

destroyed. A common affliction does indeed make us all brothers.

[BLESSING

THE DEAD BODY OF A HIPPOPOTAMUS.]

A HIPPOPOTAMUS ADVENTURE.

The monotony of ruthless slaughter, which had continued for several days,

was at last disturbed by an exciting incident in which Lieutenant Stairs

figured more conspicuously than even his adventure-loving disposition desired.

Slow progress was being made by some of the party on shore while others

were poling and paddling at equally slow pace in a half-dozen nuggers,

Stairs being in the lead, and Stanley following in his steel whale boat,

the

Advance. In a considerable cove, where the river had once made

a turn and then swept back again into its former channel, [Stair's

adventure with a bull hippopotamus] leaving a half-stagnant elbow,

several hippopotami were seen sporting, and decision was immediately made

to attack them. Stairs pushed forward, his approach being hidden by a jutting

point, until he had gained a position sufficiently near to permit an effective

shot. The nugger was now brought round to an unexpected meeting with a

large cow hippopotamus, which Stairs fired at and badly wounded. [THE

PRISON OF EMIN PASHA AND MR. JEPHSON AT DUFFILI. -- ; (See page 530.)]

In its violent struggles the animal turned over and over in the shallow

place until its movements excited the compassion of its companions, three

of which came charging to the rescue, with one uncommonly large bull in

the lead. The shallowness of the water prevented the huge animals from

diving and coming up under the canoe, as is their custom, and forced them

to make the approach in full view. Thus when the bull, re-enforced by its

almost equally dangerous companions, came rushing towards the canoe with

wide open mouth, Stairs opened fire upon it, but to so little effect that

the animal was not checked, while its rage was greatly increased. The other

three, however, were frightened by the discharge of the gun and made off

in great haste, leaving their leader to fight the battle alone. The bull,

whose head now presented a horrible sight by reason of his gaping jaws,

red and frothing, with blood pouring from three wounds that seemed to be

discharging their flood directly into his mouth, came charging onto the

canoe, which it actually seized and would have torn in pieces together

with the occupants had not those following behind in the other canoes come

up at this juncture and poured an effectual broadside of shots into the

mad monster. The result, however, was a badly broken canoe, and an impromptu

bath by Stairs, who had leaped out of the boat when he saw the enemy's

mouth apparently opened to receive him.

AMONG THE CROCODILES.

Along the Aruwimi, especially in the more desert regions, where famines

are said to be frequent, the natives are omnivorous in their diet, eating

every kind of animal food, not excepting human flesh , crocodiles, monkeys,

snakes, lizards and worms. The snake-eaters are particularly repulsive

in their appearance no less than in their habits; for not only is their

food most vile, but their filth and squalor are equally so. A group of

these miserable people gathered about a fire, cooking their evening meal

of snakes and lizards, is a sight not only appalling but one at once so

disgusting and loathsome that we sorrow because all mankind is made of

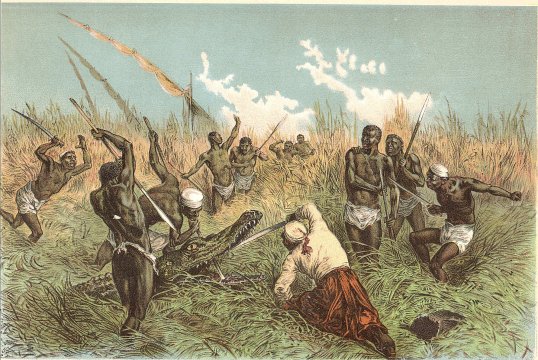

one likeness. [Novel

means of killing crocodiles]

Having no effective arms with which to hunt the Crocodiles, some of

the Aruwimi tribes exercise a cunning expedient to effect the capture of

these dangerous reptiles, It requires a cool head and steady nerves to

put the plan into practice, but these requirements are seldom wanting among

savage people. The native hunter, when he seeks this kind of game, takes

with him a very simple arm, being only a thick stick some ten inches long,

through which runs a slender piece of iron sharply pointed at both ends.

Finding his quarry asleep along some sedgy bank, he cautiously and noiselessly

approaches until within a dozen feet or more of the crocodile. The hunter

now drops down into a prostrate position and crawls carefully along towards

the reptile's mouth. When within three or four feet he makes a peculiar

clucking noise, which arouses the crocodile but does not alarm it. His

motions are now such that the creature believes a meal to be near at hand

and turns his head to seize the prey; at this moment the hunter thrusts

his instrument into the mouth of the crocodile, who seizes it with avidity

only to find itself helpless to do any harm with its teeth. Generally the

pain caused by the sharp points of the weapon makes the crocodile very

angry and in its rage pursues the hunter. In this case the creature only

hastens its doom, for the hunter can easily keep out of reach of the crocodile's

tail, which is now its only means of offence, and when it is sufficiently

far from the water the hunter boldly seizes it and either doubles the forelegs

up over the back, beats it to death with a dub, or rips it up with a sharp

piece of iron which serves the purpose of a knife. [A

crocodile snare.]

Crocodiles are also caught by means of spring-traps made by bending

over a strong sapling and attaching to the end a vine with an iron hook

fastened to it, and a hoop so set that in reaching the bait on the hook

the creature must thrust his head through the ring. When the bait is seized

the vine is loosed from its fastenings and up goes the sapling, lifting

the crocodile just high enough -- ; while the hook serves to hold

him -- ; to leave him dancing on his hind legs and tail, and strangulation

ends his troubles in the course of an hour.

This same means of catching the crocodile is employed by a half-dozen

tribes of South American Indians, and it is also used by some of the people

in South Africa.

THE WAMBUTTI DWARFS.

It will be remembered that in Stanley's first trip across the Continent,

as he came near the upper waters of the Congo he met an Arab caravan under

Tipo Tib, which he engaged to escort him a considerable distance; that

the great Arabian chief told the intrepid explorer a wonderful story about

a race of dwarfs towards the north with whom he had once come in contact

much to his own cost. The reader will also recall to mind the fact that

while making his way down the Congo Stanley had the fortune to capture

a member of the pigmy tribe, but was not able to elicit any information

from him beyond the simple fact that he, like all others of his people,

was a cannibal.

The story of Tipo Tib received partial confirmation in the capture thus

made, and also in the harrowing fears of Kabba Rega, who assured Stanley

that there was a race of dwarfs living somewhere to the west of Unyoro

of the most violently vindictive dispositions, and who, besides possessing

surprising courage, were always murderously inclined, and capable of doing

the greatest mischief. For these Kabba Rega entertained such a fear that

he spoke of them as he would of avenging spirits, with powers of the supernatural.

[A

dwarf watch tower]

That these fearful stories were a superstructure of fable built upon

a small base of facts is not surprising, and it is with no wonder therefore

that Stanley found them to be so. But the pigmies are certainly a verity,

and even this much excites our liveliest interest to know something about

them. The tribe, called Wambuttis, occupy a considerable district lying

on both sides of the Aruwimi, and nearly midway between Yambuya and Albert

Lake. Their average height is certainly not more, perhaps less, than three

feet, but occasionally specimens of the tribe may be seen five feet in

height, while there are as many of the exceptionally short that scarcely

exceed two feet; a majority of them are slightly under three feet. But

though short of stature they are uncommonly muscular and are also very

ingenious, particularly in working iron. Their chief weapons are bows and

arrows, the former being occasionally made of steel and the latter invariably

tipped with metal. The few bows, indeed the only one seen that was made

of steel, seemed to be rather experimental than practical, for it was too

stiff for even the strongest man to draw effectively. But it is very interesting

to know that the tribe make and work steel, which is a most uncommon thing

in Central Africa.

CUSTOMS AND APPEARANCE OF THE DWARFS.

The Wambuttis are fishers and hunters and pursue both callings with great

success. In hunting the largest game they go in considerable bodies, surrounding

such animals as the elephant and literally worrying it to death by persistent

pursuit and the shooting of hundreds of arrows into it. They possess considerable

quantities of ivory as trophies of the hunt, and they manifest no small

ingenuity in carving it into fantastic designs for bracelets, anklets,

armlets, and even necklaces. [DWARF

SHOOTING SOCIABLE WEAVER BIRDS.]

Contrary, however, to tradition, the Wambuttis do not wear beards, and

in all respects they have the negroid characteristics of woolly hair, black

eyes, thick lips, flat nose and large mouth. They are certainly very courageous,

but not nearly so vindictive and cunningly cruel as Kabba Rega and Tipo

Tib represented; but that they are guilty cannibalism there was not wanting

the strongest evidence. Human skulls were frequently to be seen on poles

about their villages and in a single instance a fairly well- cured human

arm was seen hanging to the outside wall of a hut. It bore the appearance

of having been smoked for a considerable time, but none of the villagers

could be induced to talk about any of their habits. In fact, there was

no one in the expedition who could understand their language.

While the Wambuttis are evidently extremely barbaric, and no doubt practise

cruelties which distinguish all barbarous tribes, yet Stanley had ocular

proof of the fact that they also possess the most admirable traits of character

and are moved by the instincts of love. There was no evidence of polygamy,

while the domestic ties were evidently very strong. Each family resided

together in an elevated hut that was thatched with grass and carried up

in a cone shape to a sharp point, or central support, which projected several

feet above the crown of the roof. During a short stay at one of the villages

a child of one the natives died, and Stanley saw the evidences of intense

grief which the event caused. The mother appeared to be crazed by her sorrow

and had to be restrained by her friends from committing some desperate

act. Another woman, probably the grandmother, judged by her appearance,

took the dead body upon her lap and poured out a libation of tears and

wailings that was deeply affecting to behold. [Adventure

in the dwarf country.]

The disposition of their dead is similar to that practised by the Sioux

Indians, the bodies being placed in rude coffins, frequently made from

the hollow of trees cut of a proper length and closed at the ends, and

then deposited on scaffolds, where they are secure from wild beasts.

[Gathering

honey]

THE QUIMBANDES.

Beyond the dwarfs, or nearer Lake Albert, lives an exceedingly fine appearing

tribe called the Quimbandes, who are chiefly noted for their physical symmetry

and the peculiar manner in which they dress the hair. Their only clothing

is a narrow leathern girdle about the loins from which hangs, before and

behind, a strip of hide, or cloth when procurable. But while they bestow

small attention to their bodies, infinite care is evidently taken with

the hair, quite as much, indeed, as is bestowed by the Manyuemas. Some

are to be seen with the hair tightly rolled, with bright feathers rising

out of a chignon, while the more fastidious contrive by some artful means

to arrange the hair, by plaiting and twisting, into the form of a Roman

helmet, while yet others present the appearance of wicker- work.

The Quimbandes are an indolent people, whose only known manufacture

is willow baskets. They live chiefly by fishing, but vary their diet of

fish by eating various insects, notably the locust -- ; our grasshopper

-- ; which is highly esteemed by them. They also gather considerable quantities

of honey, as large stores were invariably found in their villages. Their

houses are miserable pretences, made by setting up a few poles with a rack

on top, which is then covered with loose grass. A ludicrous scene was precipitated

by Mr. Williams, when he attempted to photograph a group of females who

mistook his camera for a magic gun.

[THE

DWARFS' MANNER OF DISPOSING OF THEIR DEAD.]

A TRIBE WITH TAILS.

Adjoining the Quimbandes is another peculiar tribe almost equally symmetrical

in form and greatly resembling the Bongos, but Stanley has neglected to

give us even their local designation, though from a photograph we have

[First

conflict with the natives -- ; (See page 466)] been able to make

an excellent illustration. They wear scarcely as much clothing as their

neighbors, nor do they bestow any care on the hair, leaving it to run riot

like the indifferent pure Africans that they are. But they nevertheless

have some idea of decoration, though it develops, to our tastes, in an

increasing unsightliness rather than an improvement. The women affect the

pelele, or lip ring, like some of the South American tribes, and by inserting

a bit of ivory in the lower lip gradually enlarge the wound until pieces

of bone, wood, or ivory, more than an inch in diameter, may be inserted

and worn. Besides this singular, so-called ornament, they wear a cincture

of hide, with a bundle of grass tied in front to serve the traditional

purpose of fig-leaves, and a cow-tail hangs from the belt behind, which

led to the belief among travellers that they had natural tails. The wrists

and ankles are invariably encumbered by numerous iron rings, a form of

jewelery that is strikingly common among savage people. [Scared

by Mr. Williams' camera.]

Unlike the Quimbandes, these neighbors are an agricultural people, and

are also somewhat pastoral, though their herds of cattle and sheep are

always very small. They raise grain and tobacco and give considerable attention

to poultry. Their dwellings are pretentious in size, but are so fragile

in construction and material as to serve only a short time; either a fire

burns them [The

promised land: End of the great Congo forest region. -- ; (See page

476)] or a wind- storm soon destroys them. They are made almost entirely

of grass and bear a striking, resemblance to a large wheat stack, except

that the apex, instead of being pointed, is made to assume a bushy appearance.

THE M'TEITA.

Still further eastward is the M'teita tribe, who are a picturesque people

by reason of the numerous gewgaws the women especially affect, which, while

they do not clothe or conceal the body, certainly do highly decorate.

The women are of pleasing features and often real pretty, even to the

critical eye of an American. They are especially fond of bead-work, and

the belles ornament their bodies with strings of various colored beads

wound round and round the waist, breast, neck and head. In front is worn.

a lappet of cloth or skin, also decorated with beads, and the buttock is

covered with a piece of fringed cloth, while the arms and legs bear a very

burden of rings made of ivory, iron, and occasionally of copper. The men

are not nearly so vain and are content with a plain piece of cloth about

the loins -- ; in this respect being more modest than the women

-- ; and sometimes a necklace of either beads or a small bit of leather

with some equally simple ornament strung upon it. [A

dandy]

The M'teita do a little farming and raise a few goats and sheep, but

they are chiefly traders, and as such travel considerably in Uganda, Unyoro,

Usoga, and other kingdoms about Lake Albert. They construct very crude

dwellings of grass, and with this crudeness is also found an utter lack

of comfort or convenience, the floors having no covering except a thin

layer of grass, which is not changed often enough to prevent a very foul

odor, while the sides of thatch are so loose as to freely admit both wind

and rain. But for all this they appear to be a contented, and certainly

a hospitable people. [A

M'Teita man and woman]

THE APPROACH TO LAKE ALBERT.

Stanley's approach to Lake Albert was indicated by not only a marked improvement

in the natives, whose proximity to the semi-civilized lake tribes had produced

a distinct influence for their betterment, but also the change was clearly

noticeable in the game, which became gradually more plentiful. As Stanley

has said, a considerable part of the journey was made through an almost

desert region, which was not only an untrodden wilderness, but one in which

nature had withheld her bounty. Very frequently the expedition was reduced

to such desperate straits, for want of food, that the men were almost ready

to excuse the practice of cannibalism among the people whose homes had

to be made in such a country. Stanley mentions an incident somewhat ludicrous

in its aspect, to illustrate the hunger from which the whole expedition

suffered. He had bravely endured the privations in common with his men,

and went on an allowance so small that his strength became much impaired.

On one occasion he subsisted for an entire day on a single small box of

sardines, and in the evening, seated alone in a place where he hardly expected

to be observed, he ate the last little fish and then licked the oil out

of the can as clean as ever a starving animal picked a bone. But what was

his astonishment when at last he threw the empty box away to see three

natives, who had been secretly watching him, make a violent scramble for

it, and in the struggle for its possession they fought as do hungry dogs

over a piece of meat. At length the stronger one secured the box, and spent

quite half an hour both smelling and licking it, just as Stanley himself

had done. Possibly the tin attracted their admiration, but certain it is

that they would have prized, at that time, its former contents much more,

for hunger was plainly stamped on their pinched features.

CHEER UP, BOYS!

As the country became more park-like the spirits of those composing the

expedition grew buoyant. All the way Stanley had sought to sustain their

courage by many promises both of rewards and assurances that the hardships

would soon be at an end. His words were always, "Cheer up, boys; it is

only a short distance to the station, where we shall find plenty." Thus

so cheerful did he always himself appear, as did also his lieutenants,

that the influence on the carriers was such as to keep them on the march.

To turn back and go again through the desert wilderness was not to be thought

of, hence the men could hardly consider any other alternative than that

which lay before them, but many more would no doubt have fallen exhausted

by the way had not Stanley appealed to their courage as he did. At one

place, however, there was a mutiny, which, but for Stanley's prompt action

in visiting upon the leader a swift punishment by his own hand, might have

proved quite serious. But when the leader went down under a blow from the

handle of the great leader's axe, the others, only half persuaded to make

resistance, quickly resumed their burdens, and thenceforth continued obediently

on.

A show of force is the best preventive of actual violence, and the native

Africans never respect a man so much as the one who shows determination.

[STARVATION

PRECIPITATES A SCRAMBLE.] This knowledge is what induced Stanley to

take with him a Maxim gun, quite as much as the possible need for it. A

mere exhibition of its dreadful destructiveness would serve to over-awe

the natives, and therefore Stanley had not really expected to have to put

it to a deadly use, unless it should be necessary against well- armed and

hostile Arabs, who it was not unlikely would be met, or against the Mahdi's

forces, who were believed to have Emin Pasha a prisoner. But with his keen

perception of every situation, and his great forbearance, Stanley was not

forced to slaughter the natives, and drove his way through the darkest

regions with a very small sacrifice of human life.

[STANLEY

ENFORCING ORDERS]

CHARGE OF A MAD BUFFALO.

As the expedition reached the hills that overlook the great lake basin,

which is about twenty-five miles wide, game began to appear, and to procure

a supply of fresh meat, a hunting party was organized to make a drive among

the buffaloes, several of which had been seen. The main force and the carriers

continued on the route, while Stanley, Nelson and Parke, with a dozen beaters,

started on the hunt, intending to move parallel with the marching caravan.

They had covered several miles before a herd was discovered in a position

favorable for an attack, as they did not wish to be led away any considerable

distance from the co1umn. At length a drove was descried less than a mile

off to the right, and the beaters were sent out to get on the far side

and drive them in. They accomplished their purpose so well that the buffaloes

headed directly for the hunters who had dropped down in the grass out of

sight of the game. On they came at great speed until within a few yards,

when the three hunters rose up and delivered a volley that killed two cows

and severely wounded a bull. But the latter kept on at a thunderous pace

and, as if blinded by its wound, drove directly for the column of carriers.

[A

BUFFALO'S MAD CHARGE.] The mad animal was discovered when it was perhaps

a hundred yards off, when immediately there was an excitement that did

not wait for the order to break ranks. Every man for the moment was an

independent out of file, and the hurried manner of their wild, distracted

retreat was as laughable to the disinterested spectator as it was serious

to those in flight. Burdens were dropped with extraordinary promptness

and each man prepared to climb who could find a tree, while others just

ran any way under an impromptu call to find another place. The bull perhaps

never thought of making an attack, though its lowered head and high-flying

tail certainly looked very dangerous, but it passed on through the broken

ranks and out of sight without making any other demonstration.

[A

rhinoceros creates consternation]

LOOK OUT FOR THE RHINOCEROS!

Most singular to relate, on the next day the experience with the wounded

buffalo was repeated almost identically with a black rhinoceros. The hunters

had been shooting antelopes, when a rhinoceros was jumped, at which Parke

made a shot, bringing the animal to its knees, the bullet having no doubt

struck the animal in the shoulder; but on the next instant it was up again

and became a target for Stanley, who fired an ineffectual shot, which struck

it too high on the back to penetrate the armor-like hide. The rhinoceros

now had his anger up, but instead of turning to attack, which they seldom

do, tore away and went "whoof- whoofing" towards the moving column, less

than half a mile distant. The scare of the preceding day was yet fresh,

and the sight of a charging rhinoceros filled the cavalcade with a terror

which may not even be conceived, much less described. Down went the packs

with the violence of extreme haste, and away went the carriers with a swiftness

truly astonishing, every man for himself in tumultuous eagerness to reach

safety first. The animal, seeing his supposed enemy in retreat, took courage

and tossed one of the bundles on his horn, but did no further damage, taking

himself off into the brush with this single exhibition of his temper.

A DISAPPOINTMENT.

At length Stanley and his party sighted Lake Albert, and the tedious, toilsome

and perilous journey was at an end, at least for the time being. In Stanley's

letter, found on preceding pages, is contained a description of the arrival

at Kavalli, the station on Lake Albert, and an expression of his disappointment

in his failure to meet with Emin Pasha, and his inability to procure boats

to go in search of him. To this description I may add a few facts which

Stanley has since reported by private letter. His men were so overjoyed

at the sight of the lake, where food and rest were promised, that regardless

of their heavy burdens the carriers ran at their top speed, and as the

day was very hot, some of them actually sped down the hill and into the

lake, so eager were they for the relaxation and enjoyment which its clear

cool waters offered. A stop was made of some hours on the banks, during

which the entire expedition, of men, women and children, indulged the incomparable

pleasure of a delightful bath, in which the interest was so charming that

every past misery was forgotten.

A RETURN TO THE ARUWIMI.

After sporting in the refreshing waters for a time the expedition entered

Kavalli and remained there for nearly two weeks, Stanley all the while

using every possible effort to procure boats to go on to Wadelai, and hoping

all the while that news of his arrival would reach Emin and result in a

meeting. But, as Stanley has so graphically reported, all his efforts and

hopes were in vain, so that there appeared to be nothing for him to do

but retrace his steps to Banalya, on the Aruwimi (also called the Ituri)

river, where he had left his steel steam launch, as that was the only craft

that could be obtained. Jephson had been sent on with an escort, by land,

to Wadelai, which was known to be Emin's headquarters, some time before,

and Stanley felt that by communicating a knowledge of his proximity to

Lake Albert and his purpose to afford relief, that Emin would send one

of his steamers to Kavalli to await him. In this belief, Stanley gave direction

to a Kavalli chief to report his intentions, and then prepared to plunge

again into the wilderness which promised a repetition of all the perils

and dreadful hardships through which he had just passed. His carriers were

only induced to accompany him by his agreement to pay them very large rewards,

and by threats of punishment in case of their refusal. [A

wild rush into the lake.]

This return journey was accomplished in the manner already partly told,

as also the third march which took him back to Yambuya in search of the

rear column. To the descriptions previously given, however, I am permitted

to add further particulars from Stanley letters just to hand.

After Stanley's return to Kavalli with the steam launch he still was

unable to reach Emin, because in the mean time Emin had been to that station

and went away almost immediately without informing the Kavalli chief of

his intended destination, and particularly because reliable information,

in the form of letters from Jephson, reached him giving a brief account

of a Mahdi uprising that had occurred in the mean time which had resulted

in the capture of both Emin and Jephson, who were then held prisoners at

Wadelai. Stanley's force at Kavalli was too small to cope with so powerful

an antagonist as the Mahdi, so he hurriedly left Kavalli again for Yambuya

to bring up the rear column, with which additional force he hoped to be

able to effect a rescue of Emin and Jephson, even should a battle be necessary.

DEPLORABLE CONDITION OF THE REAR COLUMN.

Writing from a village called Kaffurro, on the Kargagwe river, a branch

of the Aruwimi, Stanley says:

"My last report was sent off by Salim Behammod

in the latter part of September, 1888. Over a year full of stirring events

have taken place since then. I will endeavor to inform you what has occurred.

When we reached the camp, after great privations, but nothing to what we

were afterwards to endure, we found the 102 of the yet remaining members

of the rear column in a most deplorable condition. I doubted whether 50

of them would live to reach the lake; but having collected a large number

of canoes, the goods and sick men were transported in these vessels in

such a smooth and expeditious manner that there were remarkably few casualties

in the rear column. But wild natives, having repeatedly defeated the Ugarrowwa's

raiders, and by this discovered the extent of their own strength, gave

considerable trouble and inflicted considerable loss among our best men,

who had always to bear the brunt of the fighting and the fatigue of the

paddling. However, we had no reason to be dissatisfied with the time we

had made. When progress by river became too tedious and difficult, an order

to cast off canoes was given. This was four days' journey above the Ugarrowwa's

Station, or about 300 miles above Banalya. We decided that as the south

bank of the Ituri river was pretty well known to us it would be best to

try the north bank, although we should have to traverse for some days the

despoiled lands which had been a common centre to the Ugarrowwa's and Kilinga-Longa's

bands of raiders. We were about a hundred miles from grass land; which

opened up a prospect of future feasts of beef, veal and mutton, and a pleasing

variety of vegetables, as well as oil and butter for cooking.[Fight

at Abi Sibbam August 13, 1887, Lieutenant Stairs wounded with an arrow.]

On October 30th, having cast off the canoes, the land

march began in earnest, and two days later we discovered a large plantation

in charge of Dwaris. The people flung themselves on the plantains to make

as large a provision as possible for the dreaded wilderness ahead. The

most enterprising always secured a fair share, and twelve hours later would

be furnished with a week's provision of plantain flour. The feeble and

indolent revelled for the time being on an abundance of roasted fruit,

but always neglected providing for the future, and thus became victims

to famine after moving from this place. Ten days passed before we reached

another plantation, during which we lost more men than we had lost between

Banalya and Ugarrowwa's.

SMALL-POX AND OTHER SUFFERINGS.

Small-pox broke out among the Manyuema, and the

mortality was terrible. Our Zanzibaris escaped the pest, however, owing

to the vaccination they had undergone on board the Madura. [A

DWARIS VILLAGE.] We were now about four days' march above the confluence

of the Ihuru and Ituri rivers, and within about a mile from Ishuru. As

there was no possibility of crossing this violent tributary of the Ituri

or Aruwimi, we had to follow its right bank until a crossing could be discovered.

Four days later we stumbled across the principal village of the district,

called Andikumu. It was surrounded by the finest plantation of bananas

and plaintains we had yet seen, which all the Manyuemas habit of spoliation

and destruction had been unable to destroy. There our people, after starving

during fourteen days, gorged themselves to such excess that it contributed

greatly to lessen our numbers. Every twentieth individual suffered from

some complaint which entirely incapacitated him for duty.

The Ihuru river was about four miles south-southeast from

this place, flowing from east-north-east. It was about sixty yards broad

and deep owing to heavy rains. From Andikumu six days' march brought us

to another nourishing settlement, called Indeman, situated about four hours'

march from a river supposed to be the Ihuru. Here I was considerably nonplussed

by a grievous discrepancy between native accounts and my own observations.

The natives called it the Ihuru river, and my instruments and chronometer

made it very evident it could not be the Ihuru. We knew finally. After

capturing some Dwaris we discovered it was the right branch of the Ihuru,

called the Duru river, this agreeing with my own views. We searched and

found a place where we could build a bridge across. Bonny and our Zanzibari

chief threw themselves into the work, and in a few hours the Duru river

was safely bridged. We passed from Indeman into a district entirely unvisited

by Manyuema." Here the writer describes daily conflicts with the Wambutti

dwarfs, which he found very numerous in this region, which have already

been noticed. The Wambuttis clung to the north-east route, which Stanley

wanted to take; accordingly he went south-east and followed elephant tracks.

[Dwaris

women]

He says: But on December 9th we were compelled to halt

for forage in the middle of a vast forest, at a spot indicated by my chart

to be not more than two or three miles from Ituri river, which many of

our people had seen. While we resided at Fort Bodo, I sent 150 rifles back

to a settlement that was fifteen miles back on the route we had come, while

many Manyuema followers also undertook to follow them. I quote from my

journal part of what I wrote on December 14th, the sixth day of the absence

of the foragers: Six days have transpired since our foragers left us. For

the first four days the time passed rapidly, I might say pleasantly, being

occupied in recalculating my observations from Ugarrowwa's to Lake Albert

down to date, owing to a few discrepancies here and there, which my second

and third visit and duplicate and triplicate observations enabled me to

correct. My occupation then ended. I was left to wonder why the large band

of foragers did not return.

ON THE BRINK OF STARVATION.

On the fifth day, having distributed all the

stock of flour in camp, and having killed the only goat we possessed, I

was compelled to open the officers' provision box and take a pound pot

of butter, with two cupfuls of my flour, to make an imitation gruel, there

being nothing else save tea, coffee, sugar and a pot of sago in the boxes.

In the afternoon a boy died, and the condition of the majority of the rest

was most disheartening. Some could not stand, falling down in the effort

to do so. These constant sights acted on my nerves until I began to feel

not only moral but physical sympathy, as though the weakness was contagious.

Before night a Mahdi carrier died. The last of our Somalis gave signs of

a collapse, and the few Soudanese with us were scarcely able to move. When

the morning of the sixth day dawned, we made broth with the usual pot of

butter, an abundance of water, a pot of condensed milk and a cupful of

flour for 130 people.

CALLING A COUNCIL.

The chiefs and Bonny were called to a council.

At my suggestion of a reverse to the foragers of such a nature as to exclude

our men from returning with news of the disaster, they were altogether

unable to comprehend such a possibility. They believed it possible that

these 150 men were searching for food, without which they would not return.

They were asked to consider the supposition that they were five days searching

for food, without which they would not return, and then had lost the road,

perhaps, or, having no white leader, had scattered to loot goats, and had

entirely forgotten their starving friends and brothers in the camp. What

would be the state of the 130 people five days hence? Bonny offered to

stay with ten men in the camp if I provided ten days' food for each person

while I would set out to search for the missing men. Food, to make a light

cupful of gruel for ten men for ten days, was not difficult to procure,

but the sick and feeble remaining must starve unless I met good fortune,

and accordingly a store of buttermilk, flour and biscuits was prepared

and handed over to the charge of Bonny. In the afternoon of the seventh

day we mustered everybody besides the garrison of the camp, ten men.

SEARCHING FOR THE MISSING.

Sadia, Manyuema chief, surrendered fourteen of

his men to their doom. Kibbobora, another chief, abandoned his brother,

and Fundi, another Manyuema chief, left one of his wives and her little

boy. We left twenty-six feeble and sick wretches, already past all hope

unless food could be brought them within twenty-four hours. In a cheery

tone, though my heart was never heavier, I told the forty-three hunger-bitten

people that I was going back to hunt for the missing men. We travelled

nine miles that afternoon, having passed several dead people on the road;

and early on the eighth day of their absence from camp we met them marching

in an easy fashion. But when we were met the pace was altered, so that

in twenty-six hours from leaving starvation camp we were back with an abundance

around us of gruel and porridge, boiling bananas, boiling plantains, roasting

meat and simmering soup. This had been my nearest approach to absolute

starvation in all my African experience. Altogether twenty-one persons

succumbed in this dreadful camp.

LETTERS FROM JEPHSON.

On December 23d the united expedition continued

the march eastward, and as we now had to work by relays, owing to the fifty

extra loads, we did not reach the Ituri ferry, which was our last camp

in the forest region before emerging on grass land, until January 9th.

My anxiety about Mr. Jephson and Emin would not permit me to dawdle on

the road, making double trips in this manner, so, selecting a rich plantation

and a good camp east of the Huri river, I left Stairs in command with 124

people, including Parke and Nelson, and on January 11th I continued my

march eastward. The people of the plains, fearing a repetition of the fighting

of December, 1887, flocked to the camp as we advanced and formally tendered

their submission, agreeing to the contributions and supplies. The blood-

brotherhood was entered into, the exchange of gifts was made and a firm

friendship established. The huts of our camp were constructed by natives,

and food, fuel and water were brought to the expedition as soon as a halting

place was decided on. We heard no news of white men on Lake Albert from

the people until on the 16th, at a place called Gevaris. Messengers from

Kavalli came with a packet of letters, with one letter written on three

several dates, with several days' interval between, from Jephson, and two

notes from Emin, confirming the news in Jephson's letter. You can but imagine

the interest and surprise I felt while reading the letters by giving you

extracts from them in Jephson's own words:

DUFFILI, NOVEMBER 7th, 1888.

"DEAR SIR: I am writing to tell you the

position of affairs in this country, and I trust the letter will be delivered

to you at Kavalli in time to warn you to be careful. On August 18th a rebellion

broke out here and the Pasha and I were made prisoners. The Pasha is a

complete prisoner, but I am allowed to go about the station, but my movements

are watched. The rebellion has been got up by some half-dozen Egyptians

-- ; officers and clerks -- ; and gradually others joined, some through

inclination, but most through fear. The soldiers, with the exception of

those at Labore, have never taken part in it, but have quietly given in

to their officers. When the Pasha and I were on our way to Regaf, two men,

one an officer, Abdul Vaal Effendi, and the other a clerk -- ; went

about and told to the people they had seen you, and that you were only

an adventurer, and had not come from Egypt; the letters you brought from

the Khedive and Nubar were forgeries; that it was untrue Khartoum had fallen,

and that the Pasha and you had made a plot to take them, their wives and

children out of the country and hand them over as slaves to the English.

[ONE

OF EMIN'S IRREGULARS DISPERSING A PARTY OF REBELS.] Such words in an

ignorant, fanatical country like this acted like fire among the people,

and the result was a general rebellion, and we were made prisoners. The

rebels then collected the officers from the different stations and held

a large meeting here to determine what measures they should take, and all

those who did not join the movement were so insulted and abused that they

were obliged for their own safety to acquiesce in what was done.

THE VICTORIOUS MAHDI.

"The Pasha was deposed and

those officers, suspected of being friendly to him were removed from their

posts, and those friendly to the rebels were put in their places. It was

decided to take the Pasha as a prisoner to Regaf, and some of the worst

rebels were even for putting him in irons, but the officers were afraid

to put their plans into execution, as the soldiers said they never would

permit anyone to lay a hand on him. Plans were also made to entrap you

when you returned and strip you of all you had. Things were in this condition

when we were startled by the news that the Mahdi's people had arrived at

Lado with three steamers and nine sandals and nuggers and had established

themselves on the site of the old station. Omar Sall, their general, sent

up three peacock dervishes with a letter to the Pasha demanding the instant

surrender of the country. The rebel officers seized them and put them in

prison and decided on war. After a few days the Mahdists attacked and captured

Regaf, killing five officers and numbers of soldiers and taking many women

and children prisoners, and all the stores and ammunition in the station

were lost. The result of this was a general stampede of the people from

the station of Brodons, Kirri, and Muggi, who fled with their women and

children to Labore, abandoning almost everything. At Kirri the ammunition

was abandoned, and was seized by natives. The Pasha reckons that the Mahdists

number about 1600. The officers and a large number of soldiers have returned

to Muggi and intend to make a stand against the Mahdists. Our position

here is extremely unpleasant, for since the rebellion all is chaos and

confusion. There is no head, and half a dozen conflicting orders are given

every day and no one obeys. The rebel officers are wholly unable to control

the soldiers. The Baris have joined the Mahdists. If they come down here

with a rush nothing can save us.

"The officers are all frightened at

what has taken place and are anxiously awaiting your arrival and desire

to leave the country with you, for they are now really persuaded that Khartoum

has fallen and that you have come from the Khedive. We are like rats in

a trap. They will neither let us act nor retire, and I fear, unless you

come very soon, you will be too late and our fate will be like that of

the rest of the garrisons of the Soudan. Had this rebellion not happened

the Pasha could have kept the Mahdists in check some time, but now he is

powerless to act. I would suggest, on your arrival at Kavalli, that you

write a letter in Arabic to Shukri Aga, Chief of the Mswa station, telling

him of your arrival and telling him you wish to see the Pasha and myself.

Write also to the Pasha or myself telling us what number of men you have

with you. It would perhaps be better to write to me, as a letter to him

might be confiscated. Neither the Pasha nor myself think there is the slightest

danger now of any attempt to capture you, for the people are now fully

persuaded that you have come from Egypt and they look to you to get them

out of their difficulties. Still it would be well for you to make your

camp strong. If we are not able to get out of the country, please remember

me to my friends, etc. Yours faithfully,

"JEPHSON."

At the time the above letter was written a messenger could not be obtained

to carry it over the route to meet Stanley, who was known to be returning

to the lake, and Jephson therefore had opportunity to add two postscripts

giving ampler details of the troubles by which they had been surrounded,

and also to convey the pleasanter information of Emin's release. He therefore

added the following, under date of November 4th:

RELEASE OF EMIN, BUT SAD FOREBODINGS.

"Shortly after I had written

you the soldiers were led by their officers to attempt to retake Regaf,

but the Mahdists defended it and killed six officers and a large number

of soldiers. Among the officers killed were some of the Pasha's worst enemies.

The soldiers in all the stations were so panic-stricken and angry at what

happened that they declared they would not attempt to fight unless the

Pasha was set at liberty. So the rebel officers were obliged to free him

and sent him to Wadelai where he is free to do as he pleases, but at present

he has not resumed authority in the country. He is, I believe, by no means

anxious to do so. We hope in a few days to be at Tunguru Station on the

lake, two days by steamer from Nsabe, and I trust when we hear of your

arrival that the Pasha himself will be able to come down with me to see

you. We hear that the Mahdists sent steamers to Khartoum for re-enforcements.

If so they cannot be up here for another six weeks. If they come up here

with re-enforcements it will be all up with us, for the soldiers will never

stand against them, and it will be a mere walk-over. Everyone is anxiously

looking for your arrival, for the coming of the Mahdists has completely

cowed them. We may just manage to get out if you do not come later than

the end of December, but it is entirely impossible to foresee what will

happen."

Jephson's second postscript, dated December 18th, reads:

"Mogo, the messenger, not

having started I send a second postscript. We were not at Tanguru on November

15th. The Mahdists surrounded Duffili station and besieged it for four

days. The soldiers, of whom there are about 500, managed to repulse them

and they retired to Regaf, their headquarters, as they have sent down to

Khartoum for re-enforcements and doubtless will attack again when strengthened.

In our flight from Wadelai, the officers requested me to destroy our boats

and the advances. I therefore broke it up. Duffili is being renovated as

fast as possible. The Pasha is unable to move hand or foot as there is

still a very strong party against him, as officers are no longer in immediate

fear of the Mahdists. Do not on any account come down to us at my former

camp on the lake near Kavalli Island, but make your camp at Kavalli on

the plateau above. Send a letter directly you arrive there, and as soon

as we hear of your arrival I will come to you. I will not disguise facts

from you that you will have a difficult and dangerous work before you in

dealing with the Pasha's people. I trust you will arrive before the Mahdists

are re-enforced or our case will be desperate. Yours faithfully,

"JEPHSON."

STANLEY'S LETTER IN REPLY TO JEPHSON.

Stanley immediately returned a reply to Jephson's letter by the messengers,

in which he wrote:

"Be wise, be quick, and waste no time. Bring

Buifa and your own Soudanese with you. I have read your letters half a

dozen times over, but fail to grasp the situation thoroughly, because in

some important details one letter contradicts the other. In one you say

the Pasha is a close prisoner, while you are allowed a certain amount of

liberty. In the other you say you will come to me as soon as you hear of

our arrival here, and 'I trust,' you say, 'that the Pasha will be able

to accompany me.' Being prisoners, I fail to see how you could leave Tunguru

at all. All this is not very clear to us, who are fresh from the bush.

If the Pasha can come, send a courier on your arrival at your camp on the

lake below here to announce the fact and I will send a strong detachment

to escort him to the plateau; even to carry him if he needs it. I feel

too exhausted after my 1300 miles of travel since I parted from you last

May to go down to the lake again. The Pasha must have some pity for me.

Don't be alarmed or uneasy on our account. Nothing hostile can approach

us within twelve miles without my knowing it. I am in the thickest of a

friendly population, and if I sound a war note, within four hours I can

have 2000 warriors to assist me to repel any force disposed to violence,

and if it is to be a war, why then I am ready for the cunningest Arab alive.

I have read your letter a half-dozen times and my opinion of you varies

with each reading. Sometimes I fancy you are half Mahdist or Arabist, then

Eminist. I shall be wiser when I see you. Now, don't you be perverse, but

obey and let my order to you be as a frontlet between the eyes, and all,

with God's gracious help, will end well. I want to help the Pasha somehow,

but he must also help me and credit me."

FASCINATED BY THE SOUDAN.

"On January 16th," says Stanley, "I received with this batch of letters

two notes from the Pasha himself, confirming the above. But not a word

from either Jephson or the Pasha indicating the Pasha's purpose. Did he

still waver or was he at last resolved? With any man than the Pasha or

Gordon one would imagine that being a prisoner and a fierce enemy hourly

expecting to give the coup mortal, he would gladly embrace the first chance

to escape from the country given up by his government. But there was no

hint in the letters what course the Pasha would follow. These few hints

of mine, however, will throw some light on my postscript, which here follows,

and of my state of mind after reading these letters. I wrote a formal letter,

which might be read by any person, Pasha, Jephson or any of the rebels,

and addressed it to Jephson, as requested, but on a separate sheet of paper,

after we reached Kavalli, I wrote a private postscript for Jephson's perusal,

as follows:

KAVALLI, Jan. 18th, 3 P.M.

"My DEAR SIR: --I now send thirty rifles and Kavalli's men

down to the lake with my letters, with my urgent instructions that a canoe

should be set off. [Torturing

the Mahdi's dervishes, by order of Emin Pasha's rebel officers.] I

may be able to stay longer than six days here, perhaps ten. I will do my

best to prolong my stay until you arrive, without rupturing the peace.

Our people have a good store of beads and couriers' clothes, and I notice

that the natives trade very easily, which will assist Kavalli's resources

should he get uneasy under our prolonged visit. Should we get out of this

trouble, I am his most devoted servant and friend; but if he hesitates

again, I shall be plunged in wonder and perplexity. I could save a dozen

pashas if they were willing to be saved. I would go on my knees and implore

the Pasha to be sensible of his own case. He is wise enough in all things

else, even for his own interest. Be kind and good to him for his many virtues,

but do not you be drawn into the fatal fascination the Soudan territory

seems to have for all Europeans in late years. As they touch its ground

they seem to be drawn into a whirlpool, which sucks them in and devours

them with its waves. The only way to avoid it is to obey blindly, devotedly

and unquestionably all orders from the outside. The committee said: 'Relieve

Emin with this ammunition. If he wishes to come out, the ammunition will

enable him to do so. If he elects to stay, it will be of service to him.'

[THE

COURIER TAKING EMIN'S LETTER.] The Khedive said the same thing, and

added that if the Pasha and his officers wished to stay they could do so

on their own responsibility. Sir Evelyn Baring said the same thing in clear,

decided words, and here I am after 4100 miles' travel with the last instalment

of relief. Let him who is authorized to take it, take it and come. I am

ready to lend him all my strength and will assist him, but this time there

must be no hesitation, but positive yea or nay, and home we go.

Yours sincerely,

"STANLEY"

THE ARRIVAL OF JEPHSON.

In the course of his correspondence Mr. Stanley says:

"On February 6th, Jephson arrived in the afternoon

at our camp at Kavalli. I was startled to hear Jephson, in plain, undoubting

words, say, 'Sentiment is the Pasha's worst enemy. No one keeps Emin back

but Emin himself.' This is the summary of what Jephson learned during the

nine months from May 25, 1888, to February 6, 1889. I gathered sufficient

from Jephson's verbal report to conclude that during nine months neither

the Pasha, Casati nor any man in the province had arrived nearer any other

conclusion than what was told us ten months before. However, the diversion

in our favor created by the Mahdist's invasion and the dreadful slaughter

they made of all they met inspired us with hope that we could get a definite

answer at last. Though Jephson could only say: 'I really can't tell you

what the Pasha means to do. He says he wishes to go away, but will not

move. No one will move. It is impossible to say what any man will do. Perhaps

another advance by the Mahdists will send them all pell-mell towards you,

to be again irresolute and requiring several weeks' rest.'"

COURIER FROM EMIN.

Stanley next describes how he had already sent orders to mass the whole

of his forces ready for contingencies. He also speaks of the suggestions

he made to Emin as to the best means of joining him, insisting upon something

definite; otherwise it would be his (Stanley's) duty to destroy the ammunition

and march homeward. He continues: "February 13 a native courier appeared

in camp with a letter from Emin, and with the news that he was actually

at anchor just below our plateau camp. But this is his formal letter to

me dated the 13th:

"'SIR: -- ; In answer to your letter of

the 7th inst., I have the honor to inform you that yesterday I arrived

here with my two steamers, carrying a first lot of people desirous to leave

this country under your escort. As soon as I have arranged for a cover

for my people, the steamers have to start for Mswa Station to bring on

another lot of people. Awaiting transport with me are some twelve officers

anxious to see you, and only forty soldiers. They have come under my orders

to request you to give them some time to bring their brothers from Wadelai,

and I promised them to do my best to assist them. Things having, to some

extent, now changed, you will be able to make them undergo whatever conditions

you see fit to impose upon them. To arrange these I shall start from here

with officers for your camp, after having provided for the camp, and if

you send carriers I could avail me of some of them. I hope sincerely that

the great difficulties you had to undergo and the great sacrifices made

by your expedition on its way to assist us, may be rewarded by full success

in bringing out my people. The wave of insanity which overran the country

has subsided, and of such people as are now coming with me, we may be sure.

Permit me to express once more my cordial thanks for whatever you have

done for us.

"'Yours,'

'EMIN.' "

DISCOVERIES THAT EXCITE THE WORLD'S APPLAUSE.

Considering the trials, sufferings, and almost unparalleled hardships through

which Stanley had passed in his philanthropic mission to relieve Emin,

whose situation was certainly critical, with his power and influence destroyed

and whose most ambitious and optimistic hopes could hardly picture a pleasing

prospect, it is but natural that the great explorer should feel a sense

of disappointment, if not disgust, at the unreasonable coolness and indifference

with which Emin received his suggestions. It is not surprising either that

this want of appreciation on the part of Emin should weigh heavily on the

mind of Stanley and cause him time and again to review the privations which

he had endured, in his undertaking to perform the most magnanimous and

unselfish service for one who, while unappreciative, nevertheless needed

the aid that had been rendered. Says he in a letter now before me:

"You know that all the stretch of country between

Yambuya and this place is an absolutely new country, except what may be

measured by five ordinary marches. First, there is that dead white of the

map now changed to a dead black. I mean that the region of earth confined

between east longitude 25 degrees and south latitude 29 degrees 45 minutes

is one great compact of a remorselessly sullen forest with a growth of

an untold number of ages, swarming at stated intervals with immense numbers

of vicious man-eating savages, and crafty undersized men, who were unceasing

in their annoyance. Then there is that belt of grass land lying between

it and Albert N'yanza, whose people contested every mile of our advance

with spirit, and made us think that they were guardians of some priceless

treasure hidden in the N'yanza shores or at war with Emin Pasha and his

thousands. Sir Percival in search of the Holy Grail could not have met

with hotter opposition. Three separate times necessity compelled us to

traverse these unholy regions with varying fortunes."

REHEARSING THE PERILS OF THE MARCH.

Referring to the imprisonment of Emin, Stanley then grows reflective over

the miseries which he had so heroically endured, and says:

"Incidents then crowded fast. Emin Pasha was

a prisoner, and an officer of ours was his forced companion, and it really

appeared as though we were to be added to the list. But there is virtue,

you know, even in striving unyieldingly, in hardening the nerves and facing

those overclinging mischances without paying too much heed to the reputed

danger. One is assisted much by knowing that there are no other coups,

and the danger, somehow, nine times out of ten, diminishes. The rebels

of Emin Pasha's Government relied on their craft and on the wiles of the

heathen Chinee, and it is rather amusing to look back and note how punishment

has fallen on them. Was it Providence or luck? Let those who love to analyze

such matters reflect. Traitors without the camp and, traitors within were

watching, and the most active conspirator was discovered, tried and hanged.

The traitors without fell afoul of one another and ruined themselves. If

not luck, then it is surely Providence in answer to good men's prayers.

Far away our own people, tempted by extreme wretchedness and misery, sold

our rifles and ammunition to our natural enemies, the Manyuema, the slave

traders' true friends, without the least grace in either bodies or souls.

What happy influence was it that restrained me from destroying all those

concerned in it? Each time I read the story of Captain Nelson's sufferings

I feel vexed at my forbearance, [ALONG

THE UPPER ARUWIMI.] and yet again I feel thankful, for a higher power

than man's severely afflicted the cold-blooded murderers by causing them

to feed upon one another a few weeks after the rescue and relief of Nelson

and Parke. The memory of those days at times hardens and again unmans me."

WONDERFUL DISCOVERIES.

But with all these sufferings, including also an illness of twenty-eight

days, which came near terminating fatally, and the apparent ingratitude

of Emin, with the enthusiasm of a great explorer Stanley suddenly rises

out of his depression of spirits to voice the joy of his important discoveries,

that seem at once to compensate him for every hardship and every slight

he ever endured. Says he: "Terrible as was this last march, it was delightful

in the wonderful discoveries that we made, which crowded fast one after

another upon our surprised vision. Snowy ranges of the Ruewenzori (cloud

king or rain creator), the Semliki river, the Albert Edward N'yanza, the

plains of Noongora, the salt lakes of Kative, the new peoples: Wakonju,

great mountain dwellers of a rich forest region; the Awamba, the fine-featured

Wazonira, the Wanyoro bandits, the Lake Albert Edward tribes and the shepherd

races of the eastern uplands, then the Wanyankori, besides the Wanyaruwamba

and the Wazinja, until at last we came to a church whose cross dominated

a Christian settlement, and we knew that we had reached the outskirts of

blessed civilization."

Continuing a report of his discoveries, written Sept. 8th, 1888, from

a natunda village on the Ituri, to Col. J.A. Grant, a member of the Relief

Committee, he says:

"My DEAR GRANT: --I have only been able to write

scrappy letters hitherto, though I start them with a strong inclination

to give our friends a complete story of our various marches and their incidents.

But so far I have been compelled to hurriedly close lest I should miss

the opportunity to send them. This one, for instance, I know not how to

send at present, but an accidental arrival of a caravan or an accidental

detention of the expedition may furnish the means. I will trust to chance

and write, nevertheless. [PUNISHMENT

OF A TRAITOR.]

"You, more than any of the committee, are interested in

Lake Albert. Let us deal with that first. When on December 13th, 1887,

we sighted the lake, the southern part lay at our feet almost like an immense

map. We glanced rapidly [Stanley's

and Emin Pasha's forces on the march to the coast.] over the grosser

details, the lofty plateau, the wall of Unyoro to the east and that of

Baregga to the west, rising nearly 3000 feet above the silver water, and

between the hills the stretched out plains, seemingly very flat and grassy,

with here and there a dark clump of brushwood, which, as the plain trended

southwesterly, became a thin forest. The south-west edge of the lake I

fixed at nine miles in a direct south-westerly line from this place. This

will make the terminus of the south-west corner 1 deg. and 17 min. north

latitude, by prismatic compass, magnetic bearing; of the south-east corner

just south of a number of falls 1 deg. 37 min. This will make it about