The Plundering of Tarzan’s Africa

by Alan Hanson

Tarzan of the Apes didn’t need money. Gathering and hunting

for food, sleeping in trees, he lived off the land in the primitive areas

of Central Africa. However, his alter ego, Lord Greystoke, did need money,

a lot of it. John Clayton and his wife enjoyed all the luxuries available

to England’s privileged class in the early 20th century. Ironically, though

Tarzan had no use for money, it nevertheless became his job to provide

the fuel needed to sustain the fashionable lifestyle of Lord Greystoke.

A Lavish Existence

In the early 1900s, Lord and Lady Greystoke

lived the classical stylish existence of British colonial overseers. They

maintained expensive households on two continents — a townhouse in England

and a vast estate in equatorial Africa. The Beasts of Tarzan gives

just a glimpse of the London residence. The library had silken rugs and

a “great clock ticking the minutes in the corner.” Servants included

a maid, a chauffeur for the Greystoke limousine, the baby’s nurse, and

later young Jack’s tutor, plus an unspecified number of housemen. Lady

Greystoke, meeting the expectations of her class, was a “richly gowned

woman.”

The Greystoke African estate featured a “flower-covered

bungalow,” as well as the “barns and outhouses of a well-ordered

African farm.” A high fence guarded the “imported, pedigreed stock

in which Lord Greystoke took such just pride.” In addition to the sheep,

the Greystokes could obviously afford to import from Europe many luxury

items, such as a private family airplane and the baby grand piano Jane

played for guests. Lady Greystoke enjoyed inviting and entertaining European

visitors, obviously at great expense. What really made the African homestead

such an expensive operation was that it had to be built three times. After

its original construction, it was rebuilt twice after being burned to the

ground by Achmet Zek’s raiders in Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar and

destroyed by a German military expedition in Tarzan the Untamed.

Obviously, Lord Greystoke did not fund this privileged

lifestyle through his own labor, at least not in the conventional manner.

Through the course of 28 published Tarzan stories, only twice did John

Clayton hold down what might be called a job. In The Return of Tarzan,

for three months the French ministry of war employed Clayton, the future

Lord Greystoke, as a secret agent in North Africa. And, undoubtedly, Tarzan

received some compensation from the British military for his service as

an RAF officer, as recorded in Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”.

Both jobs were short-lived and neither played a part in building or maintaining

the Greystoke fortune.

Neither was inheritance the source of Lord Greystoke’s

wealth. It is true that when William Clayton died in 1910, the title of

Lord Greystoke, along with the family fortune passed to his cousin, John

Clayton. Burroughs never specified the size of that estate, nor does it

matter in this investigation, since within three years, Lord Greystoke

lost it all when the company in which he had invested failed.

Of course, as any reader of the Tarzan stories knows,

Lord Greystoke’s wealth was built on and replenished periodically by the

treasure Tarzan took from several lost civilizations he encountered during

his wanderings in Central Africa. His take consisted mostly of gold and

diamonds, although other gems came into his possession on a couple of occasions.

Stumbling upon a hidden fortune would satisfy the fantasies of most people,

but for Tarzan it happened over and over again. Before considering the

value, let’s take an inventory of the treasure that Tarzan carried away

from the lost lands he visited.

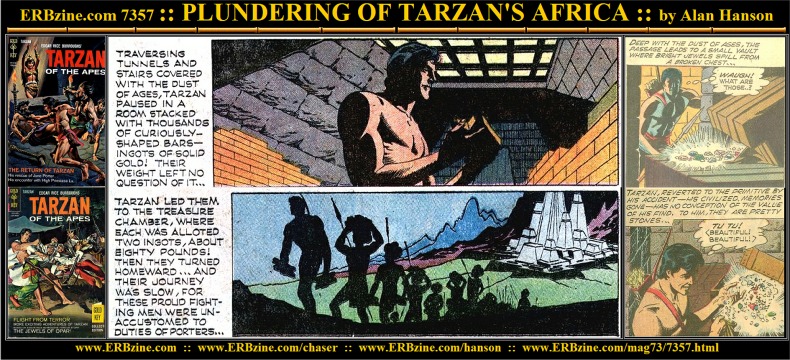

Fabulous Opar

The most well-known and reliable source

of treasure for Lord Greystoke was the gold vaults of Opar. He got his

first hint of their existence during his initial contact with the Waziri

tribe in The Return of Tarzan. It was Tarzan who first noticed

the large gold armlet on a warrior’s arm but it was the future Lord Greystoke

who realized its potential.

“For weeks he had forgotten so trivial a thing as gold,

for he had been for the time a truly primeval man with no thought beyond

today. But of a sudden the sight of the gold awakened the sleeping civilization

that was in him, and with it came the lust for wealth. That lesson Tarzan

had learned well in his brief experience of the ways of civilized man.

He knew that gold meant power and pleasure.”

The warrior Busuli told Tarzan that the yellow bangle

was taken off a dead enemy warrior after a battle near a strange city that

a Waziri party had approached a generation before. Later, after becoming

chief of the Waziri, Tarzan and 50 warriors set out to find the lost city,

the sole purpose of the expedition being for Tarzan to find more gold.

Tarzan found Opar, and there he discovered a chamber, “along the walls

of which, and down the length of the floor, were piled many tiers of metal

ingots of an odd though uniform shape.” Each of Tarzan’s 50 warriors

carried two gold ingots back to Waziri country. Since Burroughs confirmed

that each ingot weighed 40 pounds, the 100 ingots the Waziri carried away

from Opar that day totaled 4,000 pounds of virgin gold.

The value of gold fluctuates in current times, but from

1837 until 1934, the price of gold was set at a standard $20.67 per troy

ounce. Since all of the years Tarzan was collecting gold from Opar fall

within that period, it is easy to determine the monetary value of the gold

when Tarzan converted it into currency. And so, in late 1910, when Tarzan

sold his 4,000 pounds of Oparian gold, it would have brought him $1,205,747.

(Of course, Lord Greystoke would have taken payment in British pounds.)

At the end of The Return of Tarzan, the

100 ingots were loaded on a French cruiser for transportation to civilization.

Naturally, the French sailors were curious about the source of the treasure.

Tarzan refused to tell them, but he did tease them, saying, “There are

a thousand that I left behind for every one that I brought away.” (Either

he was guessing here, or he visually estimated the number of ingots in

the chamber as he was loading two on the back of each Waziri warrior.)

If this statement is true, then there were still about 100,000 gold ingots

in Opar’s treasure chamber. When he had first entered the chamber, Tarzan

guessed there were “thousands of pounds” of gold in the room. While

technically true, that was certainly an understatement, as a hundred thousand

ingots at 40 pounds apiece would weigh a whopping four million pounds.

At the set value of gold then, there was over $1.2 trillion in gold in

that chamber. Surely even the unsophisticated Tarzan at that time would

have known the disastrous effect on the value of gold were that much raw

gold dropped on the world market all at once.

Tarzan’s first trip to Opar was made in 1910, and initially

he was not quite sure what he was going to do with the resulting wealth

— except that he was going to spend it, somehow. Burroughs revealed the

ape-man’s consumer attitude in The Return of Tarzan.

“He had learned among civilized man something of the

miracles that may be wrought by the possessor of the magic yellow metal.

What he would do with a golden fortune in the heart of savage Africa it

had not occurred to him to consider — it would be enough to possess the

power to work wonders.”

Tarzan confirmed his desire to consume, or “work wonders,”

with his first load of Oparian gold when he told the French sailors, “When

these are spent I may wish to return for more.” Much of the wealth

produced by the first trip to Opar must have helped the recently married

Lord and Lady Greystoke build their African estate.

In December 1913, what remained of the Greystoke fortune

from the sale of the Oparian gold disappeared in a poor investment. “There

is no other way half so easy to obtain another fortune,” Tarzan reasoned

with Jane, “as to go to the treasure vaults of Opar and bring it away.”

And so, in early 1914 fifty Waziri warriors again accompanied their chief

to Opar and carried away another 100 gold ingots, thus giving the Greystokes

another $1,205,747 with which to “work wonders.” As Tarzan was leaving

Opar’s treasure vault, Burroughs confirmed the phenomenal amount of gold

left in the chamber.

“Tarzan turned back for a last glimpse of the fabulous

wealth upon which his two inroads had made no appreciable impression.”

(Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar)

The Jewels of Opar

Of course, as the title of that story

reminds us, the gold was not the only treasure that Tarzan obtained during

his second expedition to Opar. After an earthquake took away his memory,

Tarzan wandered through Opar, eventually stumbling on the lost city’s forgotten

jewel-room.

“Several metal-bound, copper-studded chests constituted

the sole furniture of the round room. Tarzan let his hands run over these.

He felt of the copper studs, he pulled upon the hinges, and at last, by

chance, he raised the cover of one. An exclamation of delight broke from

his lips at sight of the pretty contents. Gleaming and glistening in the

subdued light of the chamber, lay a great tray full of brilliant stones.

Tarzan, reverted to the primitive by his accident, had no conception of

the fabulous value of his find. To him they were but pretty pebbles. He

plunged his hands into them and let the priceless gems filter through his

fingers … Nearly all were cut, and from these he gathered a handful and

filled the pouch which dangled at his side.”

Burroughs never identified the kinds of gems that Tarzan

took away from Opar that day. It is known that they were of various colors.

Tarzan referred to them as “gay-colored stones,” and at night, the

“firelight playing upon them conjured a multitude of scintillating rays.”

They might all have been diamonds, since diamonds come in an array of colors.

It is possible that other colorful gems, such as emeralds and rubies, were

included.

Whatever the nature of the jewels, it was clear that the

handful that filled Tarzan’s pouch represented a fortune in the civilized

world. In the passage above, Burroughs referred to them as “priceless.”

The evil Belgian Albert Werper, who saw and coveted the gems, dreamed of

the “luxurious life of the idle rich” that the jewels would provide

him. Although a specific value can’t be put on the jewels of Opar, it is

probable that they produced Lord Greystoke a fortune at least as great

as the horde of gold he obtained during that second trip to Opar.

This double fortune, like the first one, would not last

Lord Greystoke long. While Tarzan was at Opar, the villainous Achmet Zek

was burning his African estate to the ground, and so a portion of the treasure

must have been used to rebuild the place. Then came World War I to take

the rest. A German military expedition marched in while Lord Greystoke

was away and destroyed his ranch once again. Burroughs explained in Tarzan

and the Golden Lion.

“The war had reduced the resources of the Greystokes

to but a meager income. They had given practically all to the cause of

the Allies, and now what little had remained to them had been all but exhausted

in the rehabilitation of Tarzan’s African estate.”

So, in December 1918, Tarzan against set out on the trail

to Opar. And, again, 100 gold ingots were taken from the treasure vault,

this time not by the Waziri, but rather by a group of European conspirators.

Through the vagaries of plot, the gold passed through the hands of various

villains, but it eventually wound up in Tarzan’s possession. That was another

$1,205,747 to restock the Greystoke bank account.

The Palace of Diamonds

As with his previous trip to Opar,

however, the gold was not the only treasure Tarzan obtained during his

third expedition to the lost city. In a valley behind Opar, Tarzan found

a palace that yielded a treasure much greater and easier to carry than

100 gold ingots. The ape-man took away a package of diamonds, and this

time Burroughs was much more specific about their value. The package contained

five pounds of diamonds, and when Flora Hawkes saw the contents later,

she observed there were “hundreds of them.” Flora’s fellow conspirator,

Carl Kraski, described the diamonds as, “great scintillating stones

of the first water — five pounds of pure, white diamonds, representing

so fabulous a fortune that the very contemplation of it staggered the Russian.”

Kraski later referred to the diamonds as, “the fortune of a thousand

kings.” It was a judgment by Tarzan, however, that allows an approximate

dollar value to be put on the diamonds.

“While he had been unsuccessful in raiding the treasure

vaults of Opar, the sack of diamonds which he carried compensated several-fold

for the miscarriage of his plan.”

If “several” can be equated with “three,”

then Tarzan judged the diamonds to be worth three times the value of 100

Oparian gold ingots. In that case, the diamonds would have brought Tarzan

$3,617,241, which, when added to the value of the third batch of gold,

brought Lord Greystoke’s total take from the third trip to Opar and the

Palace of Diamonds to $4,822,988. (The Greystokes had to wait awhile to

cash in on the diamonds. Conspirator Esteban Miranda got possession of

the diamonds and kept them during his year-long captivity in the village

of Obebe. They were eventually recovered by the Waziri warrior Usula and

turned over to Lady Greystoke.)

The Treasure Kept Coming

Unlike before, there is no indication

that the Greystokes squandered this huge treasure. Still, it was not to

be the last time Tarzan found a fortune among the lost peoples of Africa

and took it for his own. Far from it. In 1927, as recorded in Tarzan,

Lord of the Jungle, the ape-man followed the spoor of missing American

James Blake into the Valley of the Sepulcher. A great treasure had been

accumulated there, and it first fell into the possession of the evil Arab,

Ibn Jad.

“At his command his followers ransacked the castle

in search of the treasure. Nor were they disappointed, for the riches of

Bohun were great. There was gold in the hills of the Valley of the Sepulcher

and there were precious stones to be found there, also. For seven and a

half centuries, the slaves of the Sepulcher and of Nimmr had been washing

gold from the creek beds and salvaging precious stones from the same source

… and so Ibn Jad gathered a great sack full of treasure, enough to satisfy

his wildest imaginings of cupidity.”

By the end of the story, Tarzan had defeated the Arabs

and taken possession of the treasure. Four Waziri warriors carried it south,

bound for Lord Greystoke’s home, and eventually his bank account. A mixture

of gold and precious stones as it was, it is difficult to put a value on

the treasure of the Sepulcher, but again, for our crude accounting purposes,

let’s say that it was at least equal to one load of Oparian gold.

The next stop for the Tarzan treasure train was the Valley

of Diamonds in Tarzan and the Lion Man. There the ape-man

and actress Ronda Terry found a “bowl-shaped gully,” the floor of which

was blanketed with uncut diamonds. Rhonda envisioned a life much different

than her current one as a move stand-in.

“I shall have a villa on the Riviera , a town house

in Beverly Hills, a hundred and fifty thousand dollar cottage at Malibu,

a place at Palm Beach, a penthouse in New York.”

When Rhonda suggested bringing the entire film company

to the spot, so that all could share in the wealth, Tarzan, more experienced

in dealing with massive fortunes, gave her a lesson in treasure management.

“If you took all these diamonds back to civilization

the market would be glutted; and diamonds would be as cheap as glass. If

you are wise, you will take just a few for yourself and your friends; and

then tell nobody how they may reach the valley of diamonds.”

Rhonda agreed and took her share. “Tarzan, more sophisticated,

gathered several of the larger specimens,” noted Burroughs. Again,

with no further information provided by the author, it is difficult to

put a value on the several stones that Tarzan took. The rough stones still

needed to be cut, and it is unknown the size, number, and quality of the

resulting finished diamonds.

The final spoils of Tarzan’s travels amidst the hidden

lands of Africa were two huge gems that he took from the land of the Kaji

in 1934, as detailed in Tarzan the Magnificent. One was a

great emerald that American Stanley Wood estimated as weighing 6,000 carats.

(The most famous emerald in existence today is The Duke of the Devonshires,

which weighs just under 1,400 carats.) Wood estimated its worth at $20

million. The Englishman Lord thought it would bring 2 million pounds, which

would put it in the $5 million range. Tarzan got his hands on the Great

Emerald of the Zuli and buried it in Bantago country. The story ends with

Tarzan promising, “Some day we’ll go and get that.” The other stone

that Tarzan took was the Gonfal, the great diamond of the Kaji. Wood had

an opinion on that stone, as well. “I never saw the Cullinan, but the

Kaji diamond is enormous. It must be worth ten million dollars at least,

possibly more.”

Originally, Tarzan told both the Zuli and Kaji people

that he would return their large gems to them, but instead of keeping his

promises, he kept the stones. He gave the Kaji an imitation of the Gonfal,

while he took the real one to his home. It is uncertain just how much Tarzan

benefited from the eventual sale of the two massive jewels. At one point

he professed disdain for the wealth represented by the Great Emerald.

“I don’t want any of it,” he told Lord. “I have

all the wealth I need. I’m going to use it to get some of my people away

from Mafka. When that is done, I won’t care what becomes of it.”

And, at the end of the story, he implied the wealth that

the two stones produced would go to Stanley Wood and Gonfala, who came

away from the Kaji plateau with him. Tarzan explained it all to Wood.

“You and Gonfala should be well equipped with wealth

when you return to civilization — you should have enough to get you into

a great deal of trouble and keep you there all the rest of your lives.”

Of course, whether Tarzan kept the proceeds or gave them

to the American, the fact remains that he removed them from Africa and

he alone decided how the wealth they represented would be used.

It’s time to add up the total value of all the treasure

Tarzan found and confiscated from Africa during his many travels. Altogether,

he removed eight separate treasures to be sold at the gold and precious

gems markets in Europe. Of course, all the values that follow are estimates.

There were three separate fortunes in gold taken from Opar, totaling over

$3.6 million. The jewels of Opar added at least another million dollars.

The five-pound bag from the Palace of Diamonds was worth $3.6 million.

The value of the Great Emerald and the Gonfal, taken from the Zuli and

Kaji people, can conservatively be set at $20 million. Add to all that

the treasure taken from the City of the Sepulcher and the few large stones

collected in the Valley of Diamonds, and Tarzan’s final take was well over

$31 million.

Lost and Found — or Stolen?

So what is the significance of Tarzan’s ability to find

and his willingness to carry away so many fortunes from the darkest areas

of Africa? If Edgar Rice Burroughs is to be classified as an escapist writer,

which he is so often, then the answer is simple. Sudden financial good

fortune is a common fantasy, whether it be finding a $5 bill on the ground,

hitting the lottery, or unearthing a pirate’s treasure chest. On that level,

Tarzan’s good fortune was simply a way Burroughs satisfied his readers’

dreams of suddenly becoming fabulously wealthy.

If, however, Burroughs is to be granted a higher level

of literary respectability, as many of his proponents think he should,

then his writings must be held up to a higher, more complex level of scrutiny.

In that case, the multiple fortunes that Tarzan took out of Africa might

have a symbolic meaning far more meaningful than the dream of finding a

fortune.

For starters, it must be admitted that Tarzan stole most

of the treasure he took out of Africa. It is a nasty term, but the fact

is that seven of the eight loads of treasure he took belonged to someone

else. The three loads of Oparian gold and the bag of jewels were mined,

processed, and put in storage by the ancestors of La’s people, making them

the current owners when Tarzan came to Opar. The bag of diamonds Tarzan

took from the Palace of Diamonds behind Opar belonged to the Bolgani tribe

that inhabited the valley. They had been mining and storing the diamonds

for “countless ages.” The great sack of treasure that came from

the City of the Sepulcher was a portion of King Bohun’s riches. For over

seven centuries slaves of the Sepulcher gathered the gold and gems from

the hills of the valley. The Great Emerald and the Gonfal diamond not only

belonged to the Zuli and Kaji people, but they also played a vital role

in the political system of both societies. The only treasure Tarzan took

for which he could not be accused of theft was the handful of diamonds

he took from the Valley of Diamonds. In that case, the stones were simply

spread across a natural gully, there for the taking by anyone.

Of course, open theft on this level was not possible in

the value system Burroughs created for his ape-man. Each time Tarzan made

off with treasure, therefore, it was necessary for Burroughs to frame it

within a context that, even if not fully justifying the theft, at least

lessened the severity of Tarzan’s misconduct.

In the case of Opar, three circumstances soothed Tarzan’s

savage conscience when he took the riches of that city. Tarzan addressed

two of them in Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar.

“I shall be very careful, Jane, and chances are that

the inhabitants of Opar will never know that I have been there again and

despoiled them of another portion of the treasure, the very existence of

which they are as ignorant of as they would of its value.”

While admitting his plans to steal or “despoil”

the Oparians of their gold, Tarzan partially justified the action by noting

that the owners did not even know that the gold vaults existed. According

to Burroughs, in the treasure chamber, “ages since, long-dead hands

had arranged the lofty rows of precious ingots for the rulers of that great

continent which now lies submerged beneath the waters of Atlantis.”

The same Oparian ignorance applied to the jewel-room, which Tarzan later

raided.

“For ages it had lain buried beneath the temple of

the Flaming God, midway of one of the many inky passages which the superstitious

descendants of the ancient Sun Worshipers had either dared not or cared

not to explore.”

For Tarzan to take quantities of gold and jewels from

a people who knew not even of its existence, and who, if they had known,

would not know the value of it, was intended to make the deeds more acceptable

to the reader.

Still another extenuating circumstance was the very small

amount that Tarzan took. Although the 300 ingots of gold and the bag of

jewels provided Tarzan millions of dollars in the civilized world, it was

a tiny amount of the total treasure available. As noted earlier, on a couple

of occasions, Burroughs stressed that what Tarzan took from the gold vault

did not appreciably reduce the total amount there. In fact, using Burroughs’

numbers, of the 100,100 ingots originally in the chamber, only 300 were

removed, that being less that one-third of one percent of the total. Similarly,

in the jewel-room, Tarzan found several chests filled with brilliant cut

stones, from which he only took enough to fill the pouch dangling at his

side. Again, the taking of such a small part of the Oparian treasure helped

to validate the pilfering.

The same justification was used when Tarzan took the bag

of diamonds from the Palace of Diamonds. He took only one bag, although

there were “tier after tier of shelves, upon which were stacked small

sacks made of skins.” Unlike the Oparians, though, the Palace of Diamonds

inhabitants clearly knew of and valued their stock of diamonds.

“They have been accumulating them for countless ages,

for they mine far more than they can use themselves. In their legends is

the belief that some day the Atlantians will return and they can sell the

diamonds to them. And so they continue to mine them and store them as though

there was a constant and ready market for them.”

Only one large bagful of treasure was taken from the City

of the Sepulcher, the inference being that plenty was left behind. Although

Tarzan wound up with the treasure, he can’t be charged with the original

theft. That was done when Ibn Jad’s band sacked the city. Tarzan took possession

of the treasure after the Arabs had already transported it outside the

valley. At that point, however, Tarzan had the option of returning the

treasure to its owner, King Bohun, or keeping it for himself. Perhaps because

Bohun was a dastardly fellow, who had the nerve to kidnap the Princess

Guinalda and imprison James Blake, Tarzan’s American friend, the ape-man

felt justified in confiscating a portion of Bohun’s treasure. Call it a

fine for evil deeds done in Tarzan’s country.

In Tarzan the Magnificent, the ape-man said

he didn’t care what happened to The Great Emerald and the Gonfal diamond,

but he wound up taking them anyway. Since both stones allowed their possessors

to control the actions of people around them, perhaps Tarzan did the right

thing in removing them from these primitive societies. However, he easily

could have achieved that end by burying both stones in remote areas. Instead,

he chose to bring the stones into the civilized world where he could draw

on their commercial value.

So, in allowing Tarzan to take so much treasure from primitive

peoples, Burroughs created a struggle in the conscience of his readers,

a struggle he smoothed the edges from in several ways. Still, in the final

analysis, there is no way of getting around the fact that Tarzan took the

fabulous riches of these African peoples without their permission. What

kind of value system can justify that in the end?

A Colonial Interpretation

Tarzan’s alter ego, Lord Greystoke,

was European by culture and saw Africa as a source of wealth to fund his

affluent lifestyle, both in England and in Africa. During the colonial

period, European occupying powers often went to excess in harvesting raw

materials in their African possessions. Edgar Rice Burroughs certainly

knew this. When Mbonga’s tribe of cannibals entered Tarzan’s jungle in

Tarzan

of the Apes, Burroughs explained they were fleeing a cruel European

monarch.

“To add to the fiendishness of their cruel savagery

was the poignant memory of still crueler barbarities practiced upon them

and theirs by the white officers of that arch hypocrite, Leopold II of

Belgium, and because of those atrocities they had fled the Congo Free State

— a pitiful remnant of what once had been a mighty tribe.”

In fact, so brutal were Leopold’s tactics, which included

chopping off hands and feet of natives who failed to meet his rubber or

ivory quotas, that the population of the Congo area declined by half between

1885-1908. Mbonga’s people were not the only natives to flee into British,

French, and Portuguese controlled territories.

Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan stories portray British colonists

in a different light, that of benevolent rulers. As long as they treated

the natives well, it was acceptable to profit from ruling them. This is

one interpretation that can be placed on all the wealth that Tarzan took

out of Africa. As a reward for bringing parts of Dark Continent out of

barbarism and putting them on the road to civilization, he deserved to

profit from his just rule in Tarzan’s country. He was certainly portrayed

as a kind and civilizing leader of the Waziri, while he fought the degrading

practices of other tribes.

Of course, Lord Greystoke did not make his fortune in

Africa running in ivory or slaves. He made his in a seemingly harmless

way — stumbling upon lost hordes of hidden treasure. Symbolically, though,

the effect was the same. As a European, Lord Greystoke took for himself

huge amounts of African resources that could have been used to better the

lives of African peoples. When looked at that way, it is a troublesome

legacy for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes. But

then, we go back to the respectability Burroughs should be afforded as

a writer. If we leave him as a writer of escapist fiction, then the troublesome

issue raised above disappears. Tarzan’s trips to the treasure vaults of

Opar are reduced in significance to hitting the lottery three times. Taking

Burroughs more seriously requires asking and answering tougher questions.

Personally, I like to think Edgar Rice Burroughs was a good enough writer

to handle the tougher questions.

—the end—

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()