First and Only Weekly Online Fanzine Devoted to the Life and Works of Edgar Rice Burroughs Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages and Webzines in Archive |

First and Only Weekly Online Fanzine Devoted to the Life and Works of Edgar Rice Burroughs Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages and Webzines in Archive |

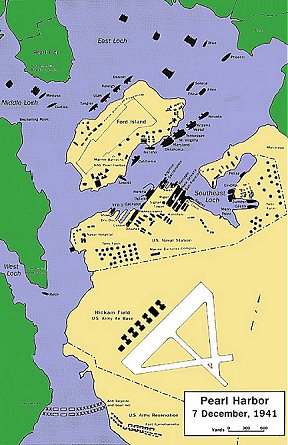

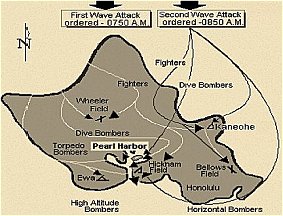

On the morning of December 7, 1941, twelve B-17 "Flying Fortress" bombers under the command of U.S. Army Major Truman H. Landon approached Hickam Field on Oahu Island, Hawaii for a fuel stop.At the time the first wave of Japanese aircraft attacked the Navy ships and airfields at Pearl Harbor, Major Landon was 150 miles north of Oahu. During landing instructions they were informed that the field was under attack by "unidentified planes." The first B-17 to approach the field was hit by gunfire and burst into flames, but landed with the blazing tail broken off. All the crew, except one, survived. Major Landon's was the second plane to land.

Meanwhile, a short distance away in Honolulu, Edgar Rice Burroughs and his son, Hulbert, heard the distant sounds of guns firing, but like almost everyone thought it was a practice exercise. They continued their tennis game, but when a bomb fell on a ship near their hotel, they finally were convinced war had arrived and started to watch in earnest.

Later, during the ensuing Pacific campaign, ERB became a war correspondent and Truman Landon was promoted to Brigadier General and put in command of the 7th Bomber Command. ERB flew to Tarawa, Eniwetok, and Kwajalein, and shared living quarters on Tarawa with General Landon. He flew with Landon on a B-24 Liberator bomber on two bombing raids over the occupied island of Jaliut and he later flew with General Landon to Eniwetok.

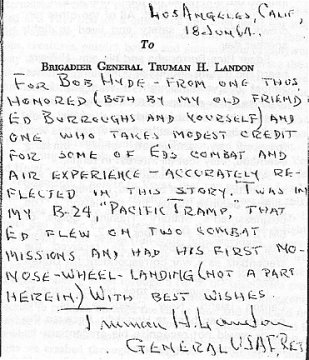

ERB returned to Honolulu where he drew on some of these wartime experiences to write Tarzan and "The Foreign Legion," from June to September, 1944. Reprinted below is what is written on the dedication page of Bob Hyde's copy of the novel which ERB had dedicated to "Brigadier General Truman H. Landon."

From Bob Hyde's

Odyssey of a Tarzan FANatic

Copyright 2002 Bob Hyde

Excerpts from an article by Capt. Donald McSherry,

U.S. Air Force Reserve and

memoirs of Capt. Richard Lane, commander of the Hickam

hospital in December 1941.

By order of Army headquarters in Washington, Schick's B-17 squadron was racing across the Pacific on a secret mission to the Philippines. With tension between the United States and Japan near the breaking point, the massive four-engine planes were bound for Clark Field, near Manila to reinforce Gen Douglas MacArthur's Far East Air Force.At 8 o'clock the next morning—Sunday, Dec. 7—the huge B-17s would come roaring in over the rooftops of Honolulu on their approach to Hickam Field, the big Army air base nestled between Pearl and Honolulu's John Rodgers Airport. As they landed, Schick and his friends would have a breathtaking, panoramic view of the mighty U.S. Pacific Fleet.

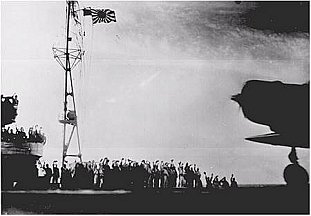

But as Schick and the B-17s hurtled toward Hawaii from the east, another force was secretly approaching America's island paradise from the west. Shrouded in radio silence and gray ocean mists, a Japanese task force of 31 ships and 30,000 men were closing in on Pearl Harbor. Poised on the decks an in the hangars of six aircraft carriers were 353 warplanes. At 8:00 a.m. on Dec. 7, the Imperial Japanese Navy would unleash the fury of those planes on a slumbering U.S. fleet.

Schick and his crewmates were excited. The first rest and refueling stop on their long flight would be on Oahu In a strange twist of fate, the fearsome B-17s, normally bristling with heavy machine guns, could not fire back. Schick's unit had picked up new Fortresses at Hamilton Field near San Francisco but, because of a bureaucratic blunder, the planes were unarmed. For nearly two days, Maj Truman Landon, commander of the 38th, had battled the bureaucrats, finally wrenching the weapons free just before takeoff. But it was too late to clean and mount them; Landon and his men would have to do it in Hawaii. Now, as Japanese planes battered them with devastating ferocity, the Forts were helpless, their guns still packed in manufacturer's Cosmoline.

Dangerously low on fuel, and with several crewmen wounded, the defenseless B-17s scattered over Oahu with the deadly Zeros in hot pursuit. Some of the Forts hobbled into Hickam while others crash-landed at tiny airstrips around the island. One came careening down on the fairway of a golf course.

Yet all of the B-17s landed intact, except for Schick's. His Fortress was the second to arrive over Pearl, and it virtually collided with the first wave of the Japanese onslaught.

As Capt. Swenson circled above the fire and chaos, trying to get landing instructions, a Japanese bullet pierced his radio compartment, igniting a bundle of magnesium flares and wounding Lt Schick in the leg. Seconds later, the B-17 was a blazing torch from mid-fuselage to tail section. To escape the flames, the crew moved to the front of the plane. in danger of a mid-air explosion, Swenson radioed the Hickam tower that he was coming in for a crash landing. Miraculously, a runway was still free of bomb craters and burning wreckage.

Descending through a storm of Japanese tracer bullets and American anti-aircraft fire, Swenson and his co-pilot, Lt. Ernest Reid, kept the crippled Fortress under control, making a near-perfect landing. But the plane's fuselage, weakened by the fire's intense heat, cracked upon impact and broke away just behind the cockpit. The forward half of the plane, carrying Schick and the crew, skidded to a stop.

As the crew jumped from the wrecked plane, they found themselves in the middle of the airfield, hundreds of yards from shelter, a fierce battle raging. The men split up. One group ran for the hangar line where planes and buildings were exploding and burning. The other group, which included Schick, sprinted for the grass on the Honolulu side of the field where Lt. Bruce Allen and his men, the first B-17 crew to land, were hugging the ground as Japanese bullets thudded around them.

But as Schick's group dashed across the runway, they were spotted by a Zero pilot who was strafing the airfield. Sweeping down from the sky, the pilot aimed his guns at the men and fired, missing all of them except the surgeon. Lt. Schick was hit in the face by a ricocheting bullet.

At the Hickam Hospital Capt. Lane the Hospital commander, came across Dr. Schick in the middle of the death and confusion of the attack. "He was a young medical officer who had arrived with the B-17 bombers from the States during the raid. When I first noticed him he was sitting on the stairs to the second story of the hospital. I suppose the reason that my attention was called to him was that he was dressed in a winter uniform which we never wore in the Islands, and had the insignia of a medical officer on his lapels. He had a wound in the face and when I went to take care of him he said he was all right and pointed to the casualties on litters on the floor and said, "take care of them". I told him I would get him on the next ambulance going to Tripler General Hospital, which I did. The next day I heard that he had died after arriving at Tripler."

The greatest tribute to Schick occurred on Aug. 17, 1942, on what would have been his 32nd birthday. On that day, Lois gave birth to Bill's son, William Richmann Schick.

B-17 Arrival at Pearl Harbor

Excerpt: The Jack M. Spangler AccountIn between the first and second wave, a B-17D from March Air force base tried to land at Hickam filed but the runway was gone. They then tried to land on our field. The other men on the north east end of the barracks manning the other 50 cal. machine gun started shooting at the B-17. It was a new model that we had never seen before that had a different kind of dorsal fin. The Major and our men were watching the B-17 from our gun station. We saw the pilot and three men from the left waist gunners position leaning out of the plane waving anything they could get hold of to let us know that they were friendly and on our side so we wouldn’t shoot them down. The Major ran over to the other gun station with his weapon drawn and threatened to shoot the gunner if he didn’t stop shooting at the B-17. He stopped shooting and they landed safely. During the second wave, we continued to fire on Japanese war planes until the guns were so hot that the bullets would no longer feed into the barrel and it would no longer fire.These guns were water cooled and we had no water. We stayed on the roof until we were sure that there were no more aircraft strafing the field. In the hours that followed, we really didn’t know what to do. Looking around me I saw total destruction of all the aircraft. We went down to the parking ramp to see if there was anything that we could salvage but it was useless.

|

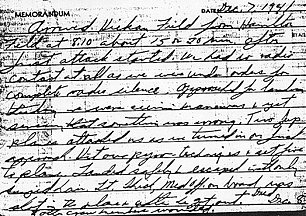

Arrived Hickam Field from Hamilton Field at 8:10 about 15 or 20 min. after first attack started. We had no radio contact at all as we were under orders for complete radio silence. Approached for landing ... sensing that something was wrong. Two Jap planes attacked us as we turned in on first approach. Hit our pyroo-techniques & set fire to plane. Landed safely & escaped with only singed hair. Lt. Thisk, Med Off. on board ups a lot in the plane and after he got out. Died Dec. 8 . No other crew members wounded. |

Shot Down at Pearl Harbor

Fifteen hours out of California, their B-17 became

the first US airplane downed by the enemy during World War II

By Ernest L. "Roy" Reid Roy Reid's eye-witness Pearl Harbor story as he experienced it from the air... Lt. Reid was in the cockpit of a B-17C as it "routinely" approached Pearl Harbor on December 7th 1941 and was shot down. This is his personal story as it appeared in the Air Force Magazine's 50th Anniversary of Pearl Harbor Commemorative Issue. Ernest L. Reid was a 2nd lieutenant in the US Army Air Forces on December 7, 1941, and flew 49 combat missions throughout the Pacific theater in World War II. He now lives in Stuart, FL and Newland, NC with his wife of 60 years, Shirley. The Reids have 5 children.

Purchase here as a Pearl Harbor Aviation Collectible

"Damn it! Those are real bullets they’re shooting. I'm hit in the leg.”With these words—the last spoken by 1st Lt. William R. Schick, to the best of my knowledge—our troubles became apparent. We were soon to become the first US airplane crew shot down in World War II.

It all began on the night of December 6, 1941, at Hamilton Field, near San Francisco, Calif. I was a member of the 38th Reconnaissance Squadron, then en route to the Philippines on a permanent change of station. Capt. R. T. Swenson was the pilot of the B-17 on which I was copilot. Aviation Cadet G. C. Beale was the bombardier, and 2d Lt. H. R. Taylor was the navigator. Lieutenant Schick, the squadron flight surgeon, had just joined the organization. He had been taken out of the Flight Surgeon School at Randolph Field, Tex., a few days before he graduated in order to go with us and had been assigned to go as a passenger on our plane.

The crew members were MSgt. L. B. Pouncy, the engineer and a veteran of many years in the Army Air Corps; Sgt. Earl T. Williams, the assistant engineer and a capable mechanic and gunner; Cpl. M. C. Lucas, the radio operator; and Pvt. Bert Lee, a gunner. All in all, it was as experienced an aircrew as could be found in the newly renamed Army Air Forces. A few members of the crew, including Captain Swenson and Lieutenant Taylor, had already made a flight to Hawaii in the spring of 1941. Lieutenant Taylor had been assigned to Ferrying Command for a few months and had made several trips to England. In those days, it took a pilot at least one year and 400 hours as copilot before he could be checked off as first pilot on a B-17. I had completed... ...my first six months and had about 100 hours logged as copilot.

Thirteen B-17s were involved in the flight to Hawaii. We were scheduled to take off at fifteen-minute intervals starting at 9:00 p.m. Western time. At about 7:00 p.m., we had a briefing by a general from Washington. I haven’t forgotten the last words he spoke to us because, only a few hours later, they took on an added significance. His words were: “Good hunting and good bombing, men.” Good hunting and good bombing! Little did any of us know just how soon we would be in a position where we wished we could do just that.

One item turned out to be of great significance: While we had all of our guns on the plane, we had no ammunition. We were scheduled to pick up the ammunition in Hawaii and carry it with us to the Philippines.

Approaching Hawaii

Fifteen minutes before we finally came to a sudden stop on the East-West runway of Hickam Field, we caught our first glimpse of land. It was Diamond Head, a welcome sight. We all looked forward to spending the rest of the day on the beach at Waikiki. As we approached Oahu, Lieutenant Schick began taking pictures with a small camera he had brought along.

As we passed Diamond Head, I noticed a few bursts of AA fire across the landmass, off to our right. I thought some American AA unit was practicing. Then I saw a flight of six pursuit ships apparently flying through a bunch of ack-ack bursts. I recall thinking that somebody on the ground was getting a little careless about where he was shooting.

It was 8:00 a.m. I remember the exact time, because I had to fill out a status report on our engines every hour on the hour. (At 7:50 a.m., Japanese Imperial Navy Commander Mitsuo Fuchida gave the final signal ordering the attack on Pearl Harbor and the other military installations in the Pacific.)

My status report took a few minutes. When I again looked up, we were on a long base leg to Hickam Field. This leg took us right down the canal toward Pearl Harbor. Captain Swenson ordered me to lower the landing gear. As I did, I noticed a great deal of black smoke coming up from Pearl Harbor. There was too much ackack around, and I began to feel that something was wrong, although I still had no idea what it was.

I asked Captain Swenson about the smoke. He thought the islanders were burning sugarcane as he had seen them do during the last trip he made to the islands. I didn’t feel too confident about that explanation because I couldn’t picture burning sugarcane making such black, oily smoke. In addition, that explanation didn’t account for all the shooting. We had made the flight under radio silence, but we were cleared to contact the tower. They had not answered any of our calls.

We had to continue our approach; our gas supply would soon become a problem. We were now at 600 feet and turned to our final approach. I got my first clear look at Hickam Field. What I saw shocked me. At least six planes were burning fiercely on the ground. Gone was any doubt in my mind as to what had happened. Unbelievable as it seemed, I knew we were now in a war. As if to dispel any lingering doubts, two Japanese fighters came from our rear and opened fire.

A tremendous stream of tracer bullets poured by our wings and began to ricochet inside the ship. It began to look as though I would probably have the dubious distinction of being aboard the first Army ship shot down.

Without waiting for an order from Captain Swenson, I pushed the throttles full on, gave it full rpm, and flicked the “up” switch on the landing gear. It seemed only logical to get quickly into some nearby clouds and try to... ...escape almost certain destruction, since we had no way of fighting back.

I had no sooner taken these steps than smoke began to pour into the cockpit. The smoke was caused by some of their tracer bullets hitting our pyrotechnics, which were stored amidships. Captain Swenson and I both realized there was now no choice but to try to land. The captain yanked the throttles off, and I popped the landing gear switch to the down position again. The wheels had only come up about halfway, and they came down and locked before we hit the ground.

While all this was happening, Lieutenant Schick, who had been standing between Captain Swenson and me, said in disbelief, “They are shooting at us from the ground.” I had just time to yell at him that the shots came from the back when he screamed that he had been hit in the leg.

Broken in Half

Seconds later, we hit the ground. Because of the smoke inside the cockpit, we couldn’t see outside very well, and the plane bounced hard. It took both of us on the controls to get the wings level after that first bounce. Then the tail came down. Almost immediately, the plane began to buckle and collapse, breaking in the middle where the fire had burned through. When that happened, we stopped very quickly.

Habits die hard. One thing a pilot does on stopping is to pull off each of the mixture controls, shut down the switches on each engine, and hit the “gang” bar, which shuts off everything even if the individual switches have not been turned off. Captain Swenson went through the whole routine even though it would have been quicker to hit the “gang” bar and leave. The copilot’s key job, after stopping, is to set the parking brakes. I did so, even though it was obvious we were not going anywhere. We found out later that the entire rear end of the plane was hanging by a few spars that hadn’t burned through. The cockpit was now completely black with smoke, and it was imperative to get out fast. I felt my way back to the top escape hatch and could make out the figure of Captain Swenson as he pulled himself up and out. The plane was in a very awkward position. The rear half, for all intents and purposes, was no longer with us, so when I jumped from the leading edge of the wing, normally about six feet off the ground, I dropped about ten feet. I felt no shock or pain when I landed.

Everyone else in the front had gotten out. We were not sure about the ones in the rear. Obeying my first impulse to get away from the ship before it blew up, I ran a few feet forward and came out of the smoke just in time to see a Japanese plane making another pass at us down the runway. I decided it was better to risk blowing up with the plane than to chance getting hit by a Japanese bullet. I ran back to our ship and hopped up on the left tire under the engine nacelle where, I figured, the mass of metal would protect me from the bullets. As soon as I heard the roar of the fighter passing overhead, I dove out of the smoke and looked around.

I spotted Captain Swenson and Lieutenant Taylor but saw none of the others. I guessed that they had already run for the safety of the row of hangars. I later learned, however, that Aviation Cadet Beale had been shot in the leg. Lieutenant Schick, who had been hit once while in the plane, had managed to get out, but a bullet fired from a Japanese plane had struck him in the head. He was picked up by an ambulance and taken to the hospital but died later that day.

Lieutenant Taylor had been hit in the ear by a piece of shrapnel, and so much blood had flowed down the creases of his neck that he looked seriously wounded. Tentatively at first and then more boldly, Captain Swenson and I wiped away at the blood until we finally came to the damaged area. It was a small nick in his earlobe, and he didn’t even know the cause of our concern because he felt no pain.

“There’s a War On!"

We then ran for the protection of the nearest hangar. Inside the hangar, a sergeant had just opened a door counter in the supply section and was laying out .45-caliber automatics and loaded ammunition clips. We......each grabbed a gun and a couple of ammo clips and headed for the back door. The sergeant yelled at us to come back and sign for the guns. One of us hollered back something along the lines of, “Forget it—there’s a war!"

In back of this hangar was the main barracks. We went inside to ask directions to the hospital, where we wanted to check on the status of our crew. It was about then that Lieutenant Taylor let me know that a good part of my hair had been singed off. That must have happened as I was going through the escape hatch—I had felt a quick flash of fire but no pain.

We headed across the parade ground to the hospital and arrived as one of the first ambulances returned from picking up the wounded. I still hadn’t grasped the amount of damage already done to Hickam Field and was thinking only in terms of our crew. The first case lifted out as we stood by the back door was not one of ours. It was a grievously wounded airman. One of his legs had been blown off at the thigh, and his side was torn apart. While I was not normally overly upset by seeing accidents or even death, this horrible sight, on top of everything else, was a little too much. I had to sit down on the hospital steps for a few minutes before I could get myself moving again.

In this short time, the scene was transformed. A steady stream of ambulances was pulling up to the front door, and wounded men were coming in under their own power or were being helped by friends. The hospital was soon full, and patients had to be set down in rows along the corridors until someone could care for them. We could not find anyone from our crew in this confusion.

There was nothing we could do there, so Captain Swenson, Lieutenant Taylor, and I decided to find the Officers Club in hopes that someone there could suggest something we could do to help. We did not know where it was, but we saw the officer’s housing area in back of the hospital, so we headed there to ask directions.

The first house we saw bore a sign that read, “Major Akers.” We rang the doorbell, and a maid came to the door. We asked her how to get to the Officers Club. She just stood there gaping at us. In retrospect, I can see why. Part of my hair was singed off, Lieutenant Taylor had blood all over his flying coveralls, and some of his blood had splashed on both Captain Swenson

and me.“I’ll Get You a Brandy”

After a few seconds, a lady’s voice came from the back of the house. She asked, “Who is it, Marie?” The maid said, “It’s some men, Mrs. Akers. I think they have been in an accident.” Mrs. Akers then came to the door and after one look said, “Oh, you poor men! Come in, and I’ll get you a brandy.”

It took us several minutes to convince her that there was a war on. She had been outside hanging up clothes and thought she was watching maneuvers. Her two children were still outside playing. She called them in. A few minutes later, the second attack started. None of us, of course, had any experience in a bombing attack, but we decided to get under the dining room table, which was massive.

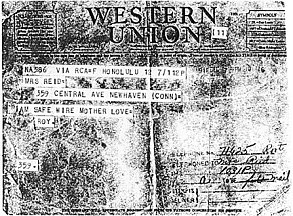

So there we were—Captain Swenson, Lieutenant Taylor, Mrs. Akers, the maid, two children, and I—all curled up under the table for five or ten minutes until the attack was over. Finally, we decided it was finished, and we crawled out. I asked Mrs. Akers if I could use her phone and charge a cable to the mainland. I got the cable operator. “Is it still possible to send a cable to the States?” I asked.

“Of course,” she said. “Why do you ask that? What is going on out at Hickam anyhow?” I told her I guessed there was a war on and to please send the following cable: “Am Safe, Wire Mother. Love, Roy.” She assured me that it would be sent. I suspect it was one of the last cables to get out that day. My wife did receive it.

We found out later that morning that the main barracks, in which we had been earlier in the day, had been badly damaged in the second attack and many men there had been killed. We spent the remainder of the day checking on the other twelve aircraft that had flown with us to Hawaii. One, the crew of which had seen us shot down, flew to the other side of Oahu and landed at a small airport. One landed on a golf course and later flew out. The others landed safely at Hickam Field. One of these had taken enemy fire but was not seriously damaged.

While walking down the edge of the runway and looking in awe at what was left of our plane after the fire had been put out, I spotted our commanding officer, Maj. Truman H. Landon, walking toward us. He looked dejected but, when he saw us, his face lit up with a big smile. He ran to us and shook hands, saying, “Thank God. I thought you might all be dead.”

The next day, I climbed up into the cockpit of our plane. I discovered four bullet holes in the armor plate behind my seat. I was one of the lucky ones on the Day of Infamy.

AIR FORCE Magazine I December 1991

B-17 Pilot's telegram to his wife on December 7, 1941:

"AM SAFE WIRE MOTHER LOVE

ROY"

In an aide memoir concerning "Defense of Hawaii" submitted by the

War Department to the President in May of 1941, the following observations were made:

Ref: Pearl Harbor B-17"*The Island of Oahu*, due to its fortification, its garrison, and its physical characteristics, is believed to be the strongest fortress in the world. "To reduce Oahu the enemy must transport overseas an expeditionary force capable of executing a forced landing against a garrison of approximately 35,000 men, manning 127 fixed coast defense guns, 211 antiaircraft weapons, and more than 3,000 artillery pieces and automatic weapons available for beach defense. Without air superiority this is an impossible task.

"*Air Defense*. With adequate air defense, enemy carriers, naval escorts and transports will begin to come under air attack at a distance of approximately 50 miles. This attack will increase in intensity until when within 200 miles of the objective the enemy forces will be subject to attack by all types of bombardment closely supported by our most modern pursuit.

"Hawaiian Air Defense. Including the movement of aviation now in progress Hawaii will be defended by 35 of our most modern flying fortresses, 35 medium range bombers, 13 light bombers, 150 pursuit of which 105 are of our most modern type. In addition Hawaii is capable of reinforcement by heavy bombers from the mainland by air. With this force available a major attack against Oahu is considered impracticable.

PROCEEDINGS IN THE U.S. SENATE "Whereas the Imperial Government of Japan has committed unprovoked acts of war against the Government and the people of the United states of America:

Declaration of War with Japan

MONDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1941

DECLARATION OF STATE OF WAR WITH JAPAN AFTER HAVING DECLARED WAR ON GERMANY AND ITALY"Therefore be it

"Resolved, etc., That the state of war between the United states and the Imperial Government of Japan which has thus been thrust upon the United States is hereby formally declared; and the President is hereby authorized and directed to employ the entire naval and military forces of the United States and the resources of the Government to carry on war against the Imperial Government of Japan; and to bring the conflict to a successful termination, all of the resources of the country are hereby pledged by the Congress of the United states."

JAPANESE MISTAKEN FOR B-17s

CONGRESSIONAL INVESTIGATION PEARL HARBOR ATTACK

TESTIMONY OF LT. COL KERMIT A. TYLER, AIR CORPS, ORLANDO, FLA., ARMY AIR FORCE BOARD

Excerpt Reference: Pearl Harbor B-1720. General FRANK. Do you remember the occasion on which a flight from the north was picked up by the Opana station?

Colonel TYLER. Yes, sir.

21. General FRANK. You remember that?

Colonel TYLER. Yes, sir.

22. General FRANK. Will you give us the circumstances surrounding that? Can you give us a narrative concerning it?

Colonel TYLER. Just as a matter of interest, I saw this lad who was keeping the historical record. There is a record made of every plot that comes into the station, and I had not yet observed that activity, so I went over to see what he was doing, and it happened to be just about 7 o'clock, or roughly thereabout; and he had these plots out probably 130 miles, which I looked at, and there were other plots on the board at that time. It was just about 7, or a little bit after, I think, and then, right at 7 o'clock, all the people who were in the information center, except the telephone operator, folded up their equipment and left. There were just the operator and myself again; and about 7:15, the radar operator from Opana called the telephone operator to say that he had a larger plot than he had ever seen before, on his 'scope, and the telephone operator relayed the call to me; so I took the call, and, inasmuch as I had no means of identifying friendly plots from enemy, nor was I led to believe that there would be any occasion to do so, I told him not to worry about it. And the next warning I had was about 5 after 8, when we received a call that there was an attack on.

23. General FRANK. What did you assume this was that was coming in? It might have been what?

Colonel TYLER. As far as I was concerned, it could. I thought it most probable that it would be the B-17's which were coming from the mainland.

24. General FRANK. YOU knew there was a flight of B-17s due in?

Colonel TYLER. I didn't have official information. You see, I had a friend who was a bomber pilot, and he told me, any time that they play this Hawaiian music all night long, it is a very good indication that our B-17s were coming over from the mainland, because they use it for homing; and when I [1100] had reported for duty at 4 o'clock in the morning, I listened to this Hawaiian music all the way into town, and so I figured then that we had a flight of B-17s coming in; so that came to my mind as soon as I got this call from him.

25. General FRANK. Did you give any thought to the fact that it might be planes from a navy carrier?

Colonel TYLER. Yes, sir. In fact, I thought that was just about an equal probability of the two.

26. General FRANK. What did you do, from then on?

Colonel TYLER. Well, there was nothing to do between the call until the attack came.

27. General FRANK. Where were you when the attack came?

Colonel TYLER. I was awaiting relief. I was due at 8 o'clock to be relieved, and there being nothing going on, I just stepped outside of the door. There was an outside door, there, and I got a breath of fresh air, and I actually saw the planes coming down on Pearl Harbor; but even then, I thought they were Navy planes; and I saw antiaircraft shooting, which I thought was practicing antiaircraft.

Excerpt from 20 Mishaps That Might Have Started Accidental Nuclear War by Alan F. Philips, M.D. It is recorded on October 22, that British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and NATO Supreme Commander, General Lauris Norstad agreed not to put NATO on alert in order to avoid provocation of the U.S.S.R. When the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered DEFCON 3 Norstad was authorized to use his discretion in complying. Norstad did not order a NATO alert. However, several NATO subordinate commanders did order alerts to DEFCON 3 or equivalent levels of readiness at bases in West Germany, Italy, Turkey, and United Kingdom. This seems largely due to the action of General Truman Landon, CINC U.S. Air Forces Europe, who had already started alert procedures on October 17 in anticipation of a serious crisis over Cuba.

October, 1962- Cuban Missile Crisis: NATO Readiness

|

|

Read about ERB's connection with the USS Shaw in

ERBzin-e

508

B-24 LIBERATOR

Consolidated B-24 "Liberator"

The B-24 was used in every combat theater of operations during World War II. Its excellent range gave the Liberator a capability for such missions as the famous raid from North Africa against the oil industry at Ploesti, Rumania on 1 August 1943. The aircraft was also suitable for long over-water missions in the Pacific Theater. More than 18,000 Liberators were built before production ended in 1945.

![]()

![]()

Volume

0718

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

All

ERB Images© and Tarzan® are Copyright ERB, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work © 1996-2002/2010/2018 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.