First and Only Weekly Online Fanzine Devoted to the Life and Works of Edgar Rice Burroughs Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages and Webzines in Archive |

First and Only Weekly Online Fanzine Devoted to the Life and Works of Edgar Rice Burroughs Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages and Webzines in Archive |

|

Spring 1970 ~ Volume I, Number 1, New Series |

The most popular fictional character of the twentieth

century

grew out of the combined talents of three Chicagoans.

Edgar

Rice Burroughs ~ James

Allen St. John ~ Johnny Weissmuller

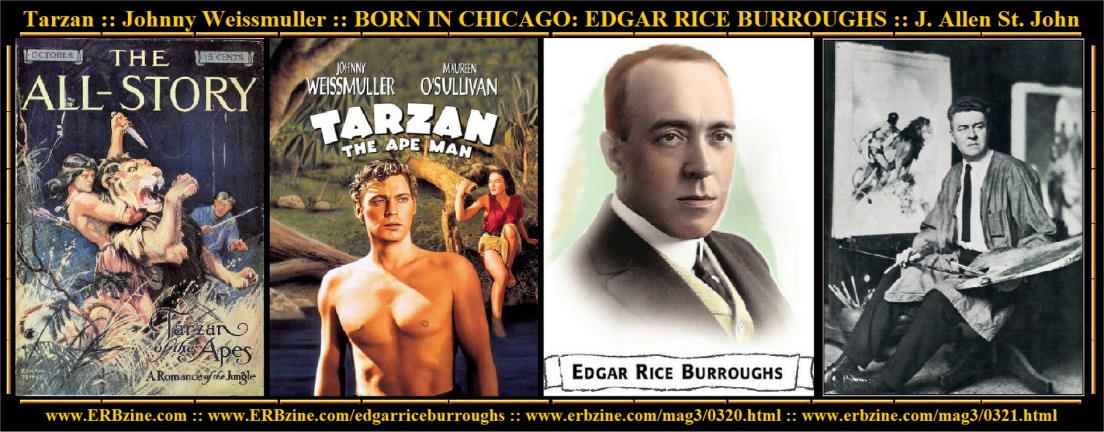

Tarzan was not born in Africa. He was born in Chicago and so was his biographer, Edgar Rice Burroughs. Chicago is in fact Tarzan town because it is not only the birthplace of Tarzan and his creator Burroughs, but also because James Allen St. John, best illustrator of Burroughs’ novels, was born on the South Side. And Johnny Weissmuller, longest lived of the movie Tarzans, got his basic education as Lord of the Jungle on the beach at Fullerton Avenue.Burroughs’ novels have sold something over fifty-five million copies, have been translated into thirty-six languages, and his most famed character, Tarzan, has had enormous coverage in such disparate media as radio, television, and comic strips, as well as on sweat shirts, and ice cream wrappers, and even two towns were named for him. St. John, a well-known painter, illustrated almost all of the Tarzan books and a great number of Burroughs’ other works. Weissmuller, undoubtedly the world’s most famous swimmer, was Tarzan of the movies for seventeen years and his ape-man’s yell loses nothing in translation for audiences all over the world – India, Africa, South America, and Asia, including even Russia and China.

I first learned about Tarzan when I was eight years old. I heard my brother dying in the backyard and ran into the house to tell my mother about it. He was, after all, her first born and she would have to learn sometime. “Ernest is being killed!” “No,” she said calmly, continuing to sort shirts, “he is merely giving vent to the victory cry of the bull ape. He does it rather well” This story is told in the family to illustrate my mother’s imperturbability, along with the yarn about the time she threw my father’s pay check in the fire thinking it was a Lucky Strike package.

She was imperturbable and she damned well had to be in those days when every able-bodied young male in the neighborhood was Tarzan and very vocal about it while hanging from our family tree. Our backyard was the largest for several blocks around, and the tree was the biggest, ideal for sitting in and hollering at each other, trying to echo Tarzan-Weissmuller’s victory cry of the bull ape. The victory cry of the bull ape, by the way, is indistinguishable from the ceremonial cry of the bull ape, which is voiced during the intricacies of the Dance of the Dum-Dum. We had a Dum-Dum, a mound of clay in the middle of our yard. This when beaten very hard with a stick sounded exactly like a mound of clay being hit hard with a stick. The tribe of Kerchak, Tarzan’s foster family, got a much better acoustical effect from their drum, but then they had more trees as sounding boards.

Each new Tarzan adventure was read by the members of the Wilson Avenue branch of the tribe of Kerchak as soon as someone in the group could afford it. The books were passed from paw to paw and we talked ape talk to each other, discussing methods of doing in lions with pocket knives and scaling rocky cliffs aided only by sinewy muscles and a grass rope. I knew Tarzan pretty well and can still quote full chapters of his life. But only recently did I find out anything much about his creator, Edgar Rice Burroughs. And his life reads like fiction, except that its author seems to have been Horatio Alger – not Burroughs.

Burroughs was born in home, September 1, 1875. The house, in what is now the 1800 block of West Washington Street was probably a substantial one since his parents, George T. and Mary E., were able to send their son to a succession of good schools and, according to one account, gave him a monthly allowance of 150 dollars. In an article in the New York Sunday World, October 27, 1929 Burroughs broadly covered his career up to the time he hit the publishing world a full circuit clout. “I was born in Chicago. After epidemics had closed two schools that I attended my parents shipped me to a cattle ranch in Idaho where I rode for my brothers who were only recently out of college and had entered the cattle business as the best way of utilizing their Yale degrees. Later I was dropped from Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass.; flunked examinations for West Point and was discharged from the Army on account of a weak heart. But my brother Henry backed me in setting up a stationery store in Pocatello, Idaho. That didn’t last long either.”

This brief admission only hints at Burroughs’ life-long affection for the military, instilled perhaps at military academics. At one time he sought a commission in the Chinese army, then seeking new talent from overseas. However they did not want him. He tried to get a commission in the Nicaraguan army, but his father had it cancelled. At age twenty he enlisted in the Seventh Cavalry but instead of fighting Indians was assigned to dig ditches. He volunteered somewhat later for the Rough Riders, but got a note of regret from Teddy Roosevelt instead of a commission. In 1900 Burroughs was again in Chicago with his wife Emma, daughter of Colonel Alvin Hulbert, owner of Chicago’s Tremont House and later of the Sherman House, as well as several other hotels in Chicago and St. Louis. Their address is given in an old city directory as 194 Park Avenue. This address is now 2004 West Maple Avenue. The following year the directory shows that they had moved to 134 Robey Street. Robey Street has since gone the way of Park and the address would now be 445 North Damen Avenue.

From 1900 to 1903 Burroughs worked for his father who was president of the American Battery Company. It was a dull life, he found, and besides he did not get along very well with his father so he and Emma joined his brothers, who had switched from cattle ranching to placer mining in Oregon. The gold mining effort failed. Edgar and Emma found themselves way out west with no job and a doubtful future. Burroughs got a job as a railroad policeman which he considered as marking time until something better came along. But nothing did and the couple returned to Chicago. The only job Burroughs could find there was a salesman peddling light bulbs and candy, door-to-door and store-to-store.

He was a great reader of want ads. According to Alva in the Saturday Evening Post of July 29, 1939: “He was constantly obtaining new positions not quite equal to his old ones. Added to that he was always ready to join his own pennilessness to the pennilessness of some other man, and to found a partnership in any naïve dream of avarice.” One of the more solid jobs was manager of Sears, Roebuck’s accounting department. In later years Burroughs said that if Sears had given him a raise he believed he deserved he would never have written a word of fiction. But he failed to get the raise and left Sears to go into an operation that might be called doubtful in the extreme. The job was with a publication called System. Burroughs’ task was to write letters of advice to businessmen. On payment of fifty dollars a year for the publication anyone wanting advice from the efficiency experts who ran the magazine could write in and be told how to be a personal or business success. Burroughs delivered, according to Johnson’s Saturday Evening Post Article, “words that rumbled with portentous wisdom but were too vague to enable any industrial baron to act on them.”

Some time later, in 1911, he was employed by a firm that prepared and distributed a product named “Alcola,” a cure for alcoholism. He was in charge of arranging the advertisements for the product, most of which appeared in pulp magazines. Checking the magazines to be sure that the ads the company paid for really appeared, Burroughs (who claimed that he had never read any kind of fiction) apparently absorbed by osmosis many of the tales of blood and thunder in which fantastic heroes performed unbelievable deeds.

Burroughs thought he could write as well or better. His poverty, thwarted ambition, and a deep desire to prove himself drove him to try it, and his incredible rise to fame and fortune began. The first success came when Burroughs sold a story to Thomas Newell Metcalf, editor of All-Story Magazine, for 400 dollars. The story was submitted in two sections. When Metcalf read the first half he wrote Burroughs that he liked it and that if the second part was as good as the first he thought he might use it. If Metcalf had not given him this encouragement Burroughs’ writing career would have ended before it began. He remembered: “I should never have finished the story and my writing career would have been at an end since I was not writing because of any particular urge to write nor for any particular love of writing. I was writing because I had a wife and two babies, a combination which does not work well without money.”

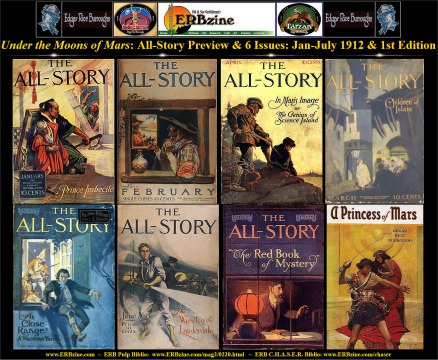

The story was titled by Burroughs “Dejah Thoris, Princess of Mars,” and was the first of the Mars stories starring John Carter, an earthman. Metcalf changed the title to “Under the Moons of Mars,” and the story appeared in the magazine as a serial in six parts beginning in February, 1912. It was not published as a book until 1917, with Burroughs’ original title restored, at least partially, as A Princess of Mars. Burroughs adapted the odd pen name of “Normal Bean” possibly to assure readers that the author was not really nutty but had a head and mind like any other earthman. In the first All-Story publication, however, some printer, believing the “Normal” to be a misprint, spelled it “Norman,” a more normal name. It was a wry twist; the first of Burroughs’ one hundred and eight titles appeared under a title the author had not selected and was signed with a name that was not only not the author’s but one he had not chosen.

“Under the Moons of Mars” was just another weird tale of impossible adventure when it appeared. But later in the same year Tarzan came swinging through the jungle, and Burroughs’ life and fortunes swung right along with him to dizzying heights never before reached by a writer of popular fiction. All-Story Magazine first printed “Tarzan of the Apes” complete in the issue of October 1912. Not until 1914 did Tarzan make it between hard covers when A. C. McClurg printed a thousand copies of the story almost as a gesture of recognition to Burroughs’ determination to see his work in book form. In the interval, several newspapers in this country and in England had printed the story as a serial.

The story of how McClurg contracted for the publication of the first Tarzan book has been preserved by David Eisenberg, a retired Near North Sider who joined McClurg on coming out of the army in 1919. He relates that, “At that time McClurg was reportedly sending Burroughs royalties of about 100,000 dollars annually, and Joe Bray, who was head of the publication department and my immediate boss at McClurg, liked to tell the saga of Burroughs’ success as an example of how perseverance and persistence could pay off. Bray maintained that he would never have signed the 1914 contract for Tarzan of the Apes if it had not been for Burroughs’ own tenacity. Every day for several months the author would come to the retail store that McClurg kept on South Wabash Avenue and report to Herb Gould, the head man – or to anyone else from the company who would listen – on the mounting popularity that Tarzan was achieving in magazines and newspapers, both here and in England. His persistent campaign eventually convinced Bray to bring out the thousand-copy edition of the first Tarzan book.”

From that small beginning the Burroughs empire arose, built of some fifty-five million copies of his books in thirty-six languages, published in every part of the world. That empire of books even has its geographical locations – two towns, one in California and one in Texas, proudly bear the respective names of Tarzana and Tarzan. And then there were the movies….

Tarzan’s enormous success in the movies and Burroughs’ share in the profits thereof are testimony that he had an almost uncanny gift for seeing where the big money of the future would come from – he had the foresight to retain future serial rights to his stories. While the magazine serials were fine and gave him a quick profit, it was hardcover books, reprint and movie rights that gave those lovely royalties that provided the greatest financial reward. The first check sent to Burroughs by All-Story for a Carter story, had written across it “for all rights.” Burroughs objected to this, and after considerable correspondence the publishers agreed that their rights were confined to the first serial and that all other rights were Burroughs’. They asked him, “Why all the fuss? What other rights are there?” Burroughs replied, “I don’t know. Movies, maybe?”

This was at the time when movies were in their infancy. Pioneers – David Wark Griffith, Maurice Costello, Lillian Gish – were still striving to create an imaginary world with something most people looked on as a toy. But Burroughs early recognized the tremendous appeal that Tarzan would have. Besides, he had plans for the ape-man. As early as 1913 he and Emma took a trip to California to see if the cinema was ready for Tarzan, but apparently they decided to let the movies get along without the help of the ape-man because a short time later, still in 1913, the couple had an Oak Park address.

Burroughs’ imagination and inventive powers, spurred by his drive for success as a writer, produced thousands and thousands of words about the two heroes he had working for him: Tarzan in Africa and John Carter on Mars. Wondrous words they were, too. Although Tarzan was my favorite character, John Carter was given some truly magnificent lines. Carter, a captain in the Confederate Army, raised himself to Mars by the simple but unscientific device of deeply wishing to be there. A swordsman, a fine gentleman and fearless leader, Carter had a style all his own. Declamatory but solid!

In The Gods of Mars he speaks these lines:

"Then my old time spirit reasserted itself. The fighting blood of my Virginia ancestors coursed through my veins. The fierce blood lust and the joy of battle surged over me. The fighting smile that has brought consternation to a thousand foemen touched my lips. I put the thought of death out of my mind and fell upon my antagonists with fury that those who escaped will remember to their dying day."Surely this can be compared in martial spirit to Homer’s line:

"Terrible was the clang of the silver bow

And ever the funeral pyres of the dead burnt brighter."Or even to the glory of a warhorse described in the Book of Job:

"He paweth in the valley, and rejoiceth in his strength: he goeth on to meet the armed men. He mocketh at fear, and is not affrighted; neither turneth he back form the sword. The quiver rattleth against him, the glittering spear and the shield. He swalloweth the ground with fierceness and rage; neither believeth he that it is the sound of the trumpet. He saith among the trumpets, Ha ha! And he smelleth the battle afar off, the thunder of the captains, and the shouting."John Carter talked like this a lot and was one hell of a fighter with swords, fists, rocks, or most anything that was handy. But it was hard for us on Chicago’s North Side to identify ourselves as closely with him as we did with Tarzan. It is hard to emulate a man, earthling though he may be with all kinds of bona fides as a hero, who can jump thirty feet and deal out wallops in mid-air to brutes who are green and have six arms. Besides, Dejah Thoris, Carter’s queen and true love, laid eggs and Carter’s son Carthoris is hatched. No, although Barsoom was a good place to visit, we did not want to live there.

Tarzan was the image we liked. Besides, you could be Tarzan all by yourself, up high on a tree branch surveying the jungle that teemed with lions, panthers, elephants, antelope, deer, boar, snakes, friendly natives who wore white hats, unfriendly ones who wore not much of anything, Roman legions, Neanderthal men, ant men, gorillas, hulking anthropoid apes (bigger than gorillas, who walked like men and talked a basic English), and assorted creatures, some of them contemporaries of Tyranosaurus Rex.

What is more, Tarzan was always stumbling over treasure, and that was to his credit. The stamp that years of hard times had left on Burroughs is probably responsible for the riches that came to Tarzan. In Tarzan of the Apes the jungle giant digs up a chest filled with gold coins. In all of the Mars series John Carter is surrounded with walls full of jewels and when anyone of social standing wears clothes at all these are of begemmed supple leather and fur. Everyone sleeps on silks and furs. The title of Burroughs’ twenty-sixth book, Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar, pretty well foretells the gem-encrusted contents. The book was published in 1918 after the author had reached a position of prominence and considerable wealth, but the memory of the lean days lingered and he made up for them in putting scenes of fabulous wealth on paper.

What better model for living could a growing boy ask for? A hero who is stronger than a gorilla, courageous, resourceful, and not only Lord of the jungle but a titled lord of the realm. Yes, Tarzan’s real name, Lord Greystoke, was inherited from his father along with all the other good traits that make up the best of an English lord and blue-blooded gentleman. All of Tarzan’s traits were admirable. He viewed his wealth with commendable calm. He was always temperate, never surly, nor did his heart pound when danger confronted him. We learned many good habits from Tarzan, except table manners – his were atrocious. We learned that gallantry to women is an honorable attitude, although the trappings of phony civilization are to be scorned. We learned that swinging from trees builds mighty muscles, or “thews”, a word all of Tarzan’s literary captives will recognize immediately. I am sure that Tarzan and his adventures among the arboreal giants accounted in that period for a large part of the popularity of traveling rings and trapezes in playgrounds throughout the nation. I know I used to spend summer vacations swinging from trapezes and traveling rings in the nearby playground, getting up at ghastly hours to get in some good practice before the crowds of other seekers after truth, virtue, and muscles lined up for their turns.

We learned it is a good thing to suffer in silence and not complain when hurt, keeping the upper lip stiff even when an arm was dislocated on the trapeze. We learned: “It is a noble and beautiful spectacle to see man raising himself, so to speak, from nothing by his own exertions; dissipating by the light of reason, all the thick clouds in which he was by nature enveloped; mounting above himself, soaring to the celestial regions, like the sun encompassing with giant strides the vast extent of the universe.” Tarzan was, indeed, Jean Jacques Rousseau’s noble savage.

Burroughs never went to Africa for background research. All that he knew about the Dark Continent was learned from books, most of them from the Chicago Public Library. Here too he did the reading of English history necessary to his second story “The Outlaw of Torn.” The novel, about Simon de Montfort and the barons’ wars of the 13th century, was finished before the author started on the first Tarzan story. Five publishers rejected it. Finally Street and Smith bought it for New-Story Magazine. It appeared in January 1914 with the cover done by N. C. Wyeth, father of Andrew Wyeth. However, “Outlaw” was not the howling success Tarzan was, and no movie, sweatshirt, or gum wrapper ever picked up the title. Burroughs’ favorite story was not about Tarzan, John Carter, or de Montfort; he favored Billy Byrne, the hero of The Mucker, a product of the streets and alleys of Chicago’s great West Side. “From Halsted Street to Robey and from Grand Avenue to Lake Street there was scarce a bartender whom Billy knew not by his first name…” Billy Byrne, a mugger, basher, all round bad fellow, wins salvation and riches through the love of a good woman and in the interval spends time in Mexico with the 13th Cavalry, a literary response to Burroughs’ lifelong ambition to be a military man.

The Mucker was written in 1913, a year divided between Chicago and California. In that year, according to a chart of word output that Burroughs kept carefully, he wrote 413,000 words, the equivalent of four 300 page books. He kept writing in California while dickering over movie possibilities of Tarzan, but nothing came of those discussions. On their return from California the Burroughs moved to Oak Park, 6415 Augusta Street, now 415 Augusta according to the Oak Park division of maps and plats. Other addresses listed in Oak Park telephone directories show them at 700 Linden Avenue in 1917, and in 1918 with an office at 1020 North Boulevard and a residence at 325 North Oak Park Avenue. In Oak Park Burroughs wrote some perfectly awful poetry which appeared in the Chicago Tribune, again over the name of Normal Bean, the pen name he had tried without success to use with his first Mars story in 1912. The Tribune got the name right, but Burroughs never again sought refuge behind a pen name in signing a book or magazine story.

Story after story poured from “his dreadful fluent pen,” as Kingsley Amis once termed Burroughs’ amazing productivity. While living in the Chicago suburb Burroughs completed forty novels. His removal from Chicago to California where he was to live for the rest of his life, was the occasion for a farewell banquet given him by the White Paper Club, an organization of writers, publishers, editors, and other forms of the genus bookman. It is obvious from the sentiments expressed at this banquet that Edgar Rice Burroughs was honored among men in the trade as a friend and good fellow as well as the most productive and highly successful of any Chicago author. Newspaper accounts of the banquet quote humorous and affectionate remarks of the speakers. Emerson Hough, author of several well-known books, including The Covered Wagon; Frank Reilly, publisher; Hiram Moe Green, editor of Women’s World; Vincent Starrett, author and poet, were among those who bade Burroughs fond farewells.

The elaborate menu printed especially for the banquet is now a collector’s item. It was illustrated by J. Allen St. John, Burroughs’ illustrator, and is a prize item in the collection of Stanleigh Vinson of Mansfield, Ohio, one of the high priests in the Burroughs sect. Vinson and over a thousand others are members of The Burroughs Bibliophiles, an international fan club started in Pittsburgh at the Science Fiction Convention in 1960. Through correspondence, yearly meetings, and fanzines (fan magazines) club members keep abreast of all new developments in the Burroughs legend and refresh their allegiance to Tarzan, John Carter and the other characters, beasts, and places that Burroughs wrought. With drawings, maps, glossaries of Burroughs-invented vocabularies, theories on the location of Tarzan’s gold vault in Opar, and even a study of Burroughs’ use of the semi-colon, the literature of Burroughs studies accumulates.

Vernell Coriell, one of the original founders, now heads the group in Kansas City, Missouri. Stan Vinson’s collection is perhaps the most extensive of any, and has supplied much of the biographical and graphic material for this article. Other information came from A Golden Anniversary Bibliography of Edgar Rice Burroughs by the Reverend Henry Hardy Heins, pastor of St. Marks Lutheran Church, Albany, New York. This work might well be one of the most complete bibliographies of one man’s work ever assembled. It contains entire listings of all the stories, manuscript material, illustrations, and advertisements, as well as several subject indexes of Burroughs’ work. Heins also gives a short biographical note on the remarkable St. John, Burroughs’ illustrator.

Concluded

in Part 2: ERBzine 0321

![]()

![]()

![]()

Volume

0320

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

& SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2006/2024 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.