Since I have been on exhibition at museums and with circuses I have been

called Joe, the Jungle Boy, the Boy Monkey, Gorilla Joe, and various other

names, but should I give you my right name you could not pronounce it.

I am a full-blooded negro boy, and was born on the Zambesi River, in

Africa, hundreds of miles beyond the Boer country. The tribe to which I

belonged was called the Mwais, and my father was chief over all. My people

numbered about 20,000 and my father had 3,000 warriors under him.

No doubt you have heard much about Africa. In that part where I was

born no one ever had seen a white man until a few years ago. Most of the

people went naked, and one tribe was always at war with another.

I can remember that we lived in rude huts and ate fruits, roots, berries,

nuts, and wild game of various sorts. Our people had no guns, but made

use of spears, clubs, and slings. No one had any knowledge beyond how to

make canoes, kill game, or fight the enemy.

My father was called a wise man as well as a brave one, but he did not

know that there were any countries outside of Africa. He believed that

he could travel to the end of the world in a week. All his time was spent

in hunting and fighting, and if anybody had told him about the oceans or

of other countries he would not have believed him.

When I was five years old I began to understand things. A short spear

and a light club were given to me, and I had to practice with them. I learned

also how to fish and set traps.

The talk was always about hunting and fighting, and when an elephant

had been killed there was a great feast for two or three days.

At ten years of age I was called a smart boy. I could find my way through

the forest, kill small game, and catch as many fish as a man. I had but

to see the track of any animal to tell what it was. I could smell a fire

a mile away, and I could see an ostrich on the plains or a man skulking

through the forest as quickly as the best of them.

One day the Makololo tribe, with whom we were always at war, came marching

through the dense forest to surprise our village and put everybody to death.

I was out alone with my spear, and I caught sight of the enemy when they

were yet two miles away.

I ran for the village at my best speed, and I do not believe that any

warrior could have run faster. I told father that the enemy were at hand,

and he at once called his warriors together.

The Makololos far outnumbered us at first, but our warriors came hurrying

up from other villages, and by and by we gained a great victory. We lost

a hundred men, but the enemy lost twice as many.

When the battle was over my father picked up a spear which lay beside

a dead man and handed it to me and said: "My son, you are but a boy yet,

but you have the courage of a man. You haven't the strength yet to hold

this spear, but you shall keep it until you are stronger. But for you we

should have beep surprised by the Makololos and none of us left alive.

When you have grown to be a man you will be a great warrior and chief in

my place."

All the warriors danced around me and shouted and patted me on the head,

and, of course, I felt very proud to be thus noticed.

I thought I could do as much as any full-grown man, and this led to

another adventure, in which I did not come out so well. I was hunting in

the forest, when I suddenly came face to face with a lion. Had I run away

he might not have followed me, as he was thirsty and on his way to a pool

to drink, but I was foolish enough to think I could kill him single handed.

I advanced upon him until he was only ten feet away, and then hurled

my spear. It was only a boy's spear, and I had only a boy's strength. The

lion was wounded in the nose, and with a roar of rage he sprang upon me

and dashed me to the earth, I remember that he picked me up and shook me

as a dog shakes a rat, and then I lost my senses.

It was an hour before I regained them, and it took me two hours more

to crawl home. One of my arms was broken, my left shoulder badly bitten,

and the lion had clawed me in a dreadful manner. I was so badly hurt that

it took me three months to recover, and all because of my foolish pride.

In my next I shall tell you how I was captured by the Makololos. and

what came of it, and I hope to interest you.

About a year after being hurt by the lion, as I told you in the first chapter,

and after I had fully recovered from my injuries, my tribe determined to

strike a blow at the Makololos. My father was very savage toward them because

they were always killing some of our men or capturing some of our women.

He called his wisest men together and they planned to attack with 2,000

warriors and destroy two or three villages and kill as many Makololo men

as they could.

These things will seem cruel to you, but you must remember that we were

savages and knew no better. We thought it right to rob and burn and kill

whenever we got the chance. If any one had told us it was wrong, we should

have laughed at him.

It was planned that my father and three of his warriors should take

a canoe and paddle up the river at night and act as spies.

We wanted to take the Makololos off their guard, you see, and make a

complete surprise. If they did not suspect they were to be attacked, it

would be a good thing for us.

I was still a young boy, and the warriors would tell me nothing; but

I did find out that my father was going in his war canoe, and I made up

my mind to go along. He would not have consented had I asked him, but I

did not ask.

I hid myself beneath some grass in the canoe, and the four men got in

and paddled away without knowing that I was there. We were very near the

Makololo village before my father discovered me, and you can guess he was

greatly surprised.

"My son, I ought to cuff you soundly and throw you over to the crocodiles,"

he sternly said; "but now that you are here I shall make use of you. I

know you to be as brave as a man, while you are small of body, and can

go where a man cannot.

"We are now going to land, and we will wait by the shore while you slip

into the Makololo village and see what is going on. I am sure you will

find out everything we want to know and come back safely."

I was glad to hear my father talk thus, and glad to go on the adventure.

I knew that if I was captured in the village the Makololos would give me

a cruel death, but I was sure that I could spy about and get away all right.

The canoe was headed for the shore just before we reached the village,

and as I stepped on land my father patted me on the shoulder and whispered

that he was proud of me.

It was no use for him to tell me how to act, for I had learned all that

long ago. There were hyenas and jackals in plenty in the forest, and there

was also a lion wandering about and uttering savage roars, but I kept on

my way and felt no fear.

In a little time I was in the village. I found the people all asleep,

and I wandered here and there without meeting a single person.

By and by I reached into the door of one of the huts and seized a warrior's

spear to carry back and show my father. I was almost clear of the village

when misfortune, beset me. I stepped into a trap which had been set to

catch a hyena, and as I was caught by the foot the surprise and the pain

made me call out.

In a minute the Makololos were pouring out of their huts to see what

was the matter, and they found me held fast.

They knew me at once for one of the Mwais, and they knew I had come

to spy. More than that, they knew me to be the boy who had warned our village

when they had come to attack it, and they were almost as much rejoiced

as if they had captured my father himself.

They lighted fires and danced around, and warriors were sent out to

see if any others were prowling about. My father and his companions had

to paddle away in great haste, and from that time to this I have not seen

him. He must have known by the yelling that I had been captured, and I

am sure he felt bad to know it and to be helpless to aid me.

At first, when the Makololos poured out on me I was frightened, but

after a bit I made up my mind to act like a man. They would be sure to

put me to death, but I would not have it go back to my tribe and my father

that I was afraid.

"Yes, I am the boy who warned our village," I replied to them, "and

if I had not stepped into this trap you would not have made me prisoner.

You need not shout so loudly over my capture, for I am not at all afraid

of you."

"He shall die! He shall die!" shouted the men, and the women and boys

picked up sticks and struck me with them and spat in my face.

In my next I will tell you what death they were going to give me and

how a poisonous snake saved me from having to run over a bed of hot coals.

It was about midnight that I was captured by the Makololos, as described

in the last chapter, and from that hour until daylight the village was

greatly excited. I was placed in a hut and two guards stationed over me,

and all night long the women and children crowded as near as they could,

calling me names and telling what my punishment should be. The guards did

not insult me or try to hurt my feelings. On the contrary, one of them

said:

"Boy, it was a brave thing for you to come spying into our village,

and we know you would have escaped safely but for the trap into which you

stumbled. We are sorry that you have got to die."

Soon after daylight I was given something to eat, and was then taken

to the chief's house. I had often heard the chief spoken of in our village,

and I knew that he was a man without mercy. He was jealous of my father

and hated him, and, of course, would delight in torturing me. The chief

and ten of his leading men sat within the house, and when I stood before

them, he said:

"Boy, I am more pleased than if we had captured ten of your father's

bravest warriors. It will make his heart sore when he hears how you died.

Ah! but you are ready to weep and beg of me to spare your life."

"It is not so," I replied. "The Mwais do not weep before their enemies."

"But I will make you weep like a sick babe, and you shall wish you had

never been born. The Mwais are only children."

"And the Makololos are only dogs," I replied.

You see, among savage people, even the children are expected to be brave.

The prisoner who is afraid is looked upon with contempt. Had I shed tears

and begged for my life, the chief would have thrown me to the dogs to be

eaten alive, and all the people of my tribe would have been ashamed of

me. I wanted to die the death of a man, and so I used bold language. My

words angered the chief, and yet he saw that I was a brave boy. He looked

at me awhile, and then said:

"One time you ran very fast and warned the people that we were coming

to attack the village. Yes, you ran very fast, but I think I can make you

run faster."

I knew what he meant by that, for I had heard our warriors talk of it.

He would have women and children spread hot coals over the ground and then

make me run over them. I was taken back to the hut while wood was gathered

and fires built, and it was an hour before they were ready for me.

I was about to be taken out, when the chief's favorite wife was bitten

by a poisonous snake as she moved through a patch of weeds. There was great

excitement at once, and for a few minutes I was forgotten. I heard the

people saying that she must die, and that the people would mourn her loss,

and I said to my guards:

"Your chief is going to put me to a cruel death, but his wife is not

to blame. Go and tell him that I can. cure her of the bite."

One of the men hurried away, and it was only a couple of minutes before

the chief came to the hut and called out:

"Boy, do you mean what you say? Can you stop the poison and save my

wife's life?"

"I surely can," I replied.

"I do not want her to die, but yet if you save her I shall not let you

go. This much I will do, however. We will not burn you nor cut you with

knives, but tonight we will tie you to a tree in the forest and let you

be eaten by lions or hyenas."

Every one in our tribe knew what to do for snake bites. A certain weed

that grew in the hills was a sure cure, and most of our people carried

a little bag of it suspended from the neck. They had not taken mine away

from me, and when I was hurried into the presence of the weeping woman

I bade her chew some at once. She did so, and before the contents of the

bag had been used up she was out of danger. When the chief knew this he

was greatly pleased, and, smiling at me, he said:

"You Mwais are great people, and you are indeed a clever boy. I wish

I could send you home in safety, but my people would not permit it. To-night

you shall be tied to a tree in the woods, and the wild beasts will give

you a quick death."

In my next I will tell you how the chief's orders were carried out,

and how it happened that I was not destroyed by lions or hyenas.

During the rest of the day, after saving the life of the chief's wife,

I was treated well. I got plenty to eat and drink, and orders were given

that no one should annoy me.

I hoped that my two guards would grow careless, and that I might have

a chance to dash for the woods, but they were keen fellows and kept sharp

watch on me. Of course, I knew what the forest was at night. In Central

Africa there is no twilight. As soon as the sun goes down darkness comes

on, and all the wild beasts who have been asleep during the day come forth

to drink and satisfy their hunger. There were, lions, wolves, hyenas, and

panthers in plenty, with many poisonous serpents, and if I was tied to

a tree I could look for death within an hour.

I tried not to think of it, as I wanted to go forth with a brave heart,

and I was talking and laughing with my guards when the chief came for me

about an hour before sundown. He seemed surprised to find me in good spirits,

and, placing his hand on my shoulder, he said:

"I am sorry for you, boy, but you must die. You are only a boy, and

yet you are as brave as any man I ever saw. I shall send word to your father

that you died as a chief's son should."

I was then taken into the forest, a full mile from the village, and

made secure to the trunk of a banyan tree. My hands were tied behind me,

and then to the tree, and when they were through I knew I could not get

away. My feet were left free, and there was no gag put in my mouth to prevent

me from calling out, but I could not expect to frighten away a lion by

my shouts or defend myself against a hyena with my feet. Some of the people

laughed at me as they went away, but others cast looks of pity.

The crowd had hardly left me when darkness came and I heard a hyena

sniffing about. Ten minutes later I heard the roar of a lion close at hand,

and presently I caught sight of the king of beasts. He marched along, making

a gurgling noise in his throat, and finally stopped not more than twenty

feet away. Of course, he could see me better than I could see him, and

no doubt he wondered what I was doing there and why, I stood so still.

I expected he would spring upon me, as he must have been hungry, but as

I neither moved nor shouted, he became puzzled and afraid, and finally

walked off. You may believe I was glad to see him go, though I knew he

would hardly get out of sight when, the hyenas would gather.

It turned out so. In a little time at least twenty of the fierce and

snarling beasts were skulking around me, and now and then, one came so

near that I could have kicked him. I did not do so, however. I simply stood

quiet, and the hyenas were for some time afraid of me. By and by their

hunger got the better of them, and they had gathered in a pack to make

a rush on me when all of a sudden every beast ran away as hard as he could

go.

I heard a crashing in the underbrush, and I thought I caught the voices

of human beings, and next moment five or six men gathered around me. I

thought they were Makololos who had come to set me at liberty, and I was

about to say that I was glad, when my eyes told me that my visitors were

not men. One of them put his face close to mine, gritted his teeth, and

uttered a "hu!"' and then I knew what they were. They were gorillas. I

had never seen one before, because they were not to be found on our side

of the river, but many a time I had heard the men of our tribe tell about

the fierce monsters.

I expected to he killed at once, but to my surprise the beasts laid

their paws on me in a kindly manner. When they found that I was tied to

the tree one of them bit through the bark rope and released me. I was then

pushed along in a gentle way, and understanding that they wished me to

go with them, I followed the gorilla in the lead. Where they were going

I could not guess, but I knew I was their prisoner and could not resist.

In my next story I will tell you how I began life among the gorillas,

and I think you will be much interested. I believe I am the only person

ever carried off by them who lived to tell his adventures.

In my last chapter I told you of my capture by the gorillas, and of my

following them through the forest in the darkness. How far we traveled

I do not know, but I should say as much as fifteen miles. It was far easier

work for them than for me. as they could see much better. I grew very tired

after a while, and one of the beasts picked me up and swung me over his

shoulder as if I were only a doll.

We passed through three or four jungles, crossed several creeks, and

after a while came to a stop in the dense, dark woods. The gorilla who

had me on his back climbed a tree and swung me off on to a bed of sticks

and grass, and I was so worn out and sleepy that I was asleep in five minutes.

It was after sunrise next morning when I awoke and saw a curious sight.

There were as many as fifteen gorillas, great and small, sitting on the

branches and looking at me with the greatest curiosity. I was as black

at they were, but they knew I was not one of them. When I sat up they all

uttered a "Hu!" and began to move about, and the biggest gorilla of all,

who was probably the one who had carried me on his back the night before,

picked me up, descended the tree, and placed me on my feet. He seemed to

reason that I was hungry and thirsty, and he led the way to a creek near

by, and then to a tree loaded with wild oranges. All the others followed,

making strange noises as if talking to each other, and I realized that

I was a sort of circus to them.

When I looked around me I saw that every animal had a nest in a tree.

These nests were at least twenty feet above the ground and very solidly

built. Most of the sticks used in them were larger than my arm and they

were fastened so securely that no gale could bring the nest down.

As I stood looking around, every gorilla came up and passed his hands

over my body. I was as naked as they, but I had no fur. They were not only

puzzled over this, but over the hair on my head. They moved about most

of the time on their four legs, while I stood upright, and this fact seemed

to make them wonder. Some of them chattered at me, as if asking questions,

and, of course, I could not understand or reply. I knew that they were

gorillas, but they could not tell whether I was an animal, or a human being.

After the gorillas had examined me for an hour, the big one said something

to them, and they began to gather sticks and grass to make me a nest in

a tree. I wanted them to understand that I preferred to live in a hut on

the ground, and I was looking for a place to build one when they came around

me and chattered and made signs that if I remained on the ground at night

I would be in danger from the beasts of prey. When this became plain to

me I climbed a tree and helped to make my own nest or bed. I do not know

that mine was any stouter than theirs, but it had more grass and was softer.

It was noon when we had finished the bed, and then the gorillas all sought

their nests and went to sleep. I did the same, and I observed that one

of them watched me for a time as if he had been told that I might try to

get away.

Late in the afternoon we all awoke, and our first act was to get drink,

and food. In an African forest there are twenty different kinds of wild

food which one can gather at short notice, so there was no fear that I

should have to go hungry. The gorillas seemed to like pretty much what

I liked, but they dug up and devoured a certain root that sickened me after

one taste.

After eating what might be called supper, the beasts became playful

and indulged in many tricks. Any one of them could swing himself from tree

to tree almost as fast as I could run, and the youngest among them could

break a stick as thick as my arm. They encouraged me to frisk around and

climb, but I was awkward and clumsy compared to them. No boy can begin

to do the smart things he sees a monkey do in the Zoo.

We went to bed soon after dark, and I lay thinking a long time before

I could close my eyes. It would have been bad enough to be prisoner to

the Makololos, but here I was among the gorillas, and I knew from their

actions that they meant to keep me with them.

In my next I will tell yon how a big serpent came to disturb us, and

how I lassoed a lion.

After I had been with the gorillas three or four days they appeared to

accept me as one of the family, and no longer watched me for fear I should

run away. There were just fifteen of the beasts, and they dwelt together

in the greatest good nature. They had no fear of anything in the forest

and if an elephant, rhinoceros, or buffalo came near our home he was attacked

at once and put to flight.

My first adventure occurred within a week, and I had a narrow escape

from death. It was about 3 o'clock in the afternoon, and we were all asleep

in our beds when I suddenly awoke to find a monstrous serpent in the tree

with me. His head was not ten feet away when I sat up, and in another moment

he would have bitten me. I had seen all kinds of snakes, and I knew this

one to be an anaconda. I did not call out or rise to my feet, but simply

threw myself over the ridge of the nest and went tumbling to the ground,

twenty feet below. The serpent darted at me as I fell, but I was too quick

for him.

The noise of my fall awoke the gorillas, and as soon as they saw the

snake there was the greatest excitement. Their scolding and chattering

and screaming could have been heard a mile away. Each beast armed himself

with a club, and they began to close in on the anaconda. I stood at a safe

distance and looked on. The serpent at first tried to get away, but when

he found he could not he took two or three turns around a big limb and

made ready to fight. The gorillas did not rush in on him at once, but got

above and below and all around him. When he struck at one, others would

be ready to hit him.

The fight lasted half an hour. The serpent was hissing and striking

and keeping the gorillas off, when they suddenly bounded in with screams

and shrieks and battered him with their clubs until he fell to the ground

a helpless mass. Then they came down to me to see if I was hurt, and when

they found that I was all right they frisked around and appeared to be

highly pleased. It was well for me that I awoke when I did. The anaconda

had fangs over an inch long, and would have killed me if he had bitten

me.

After the serpent had been killed, the gorillas armed themselves with

fresh clubs and we went prowling through the forest for a mile around to

see if the anaconda had a mate in hiding anywhere. We looked up among the

trees and into the thicksets and vines, and kept up the search for two

hours, but nothing came of it. The serpent they had killed had probably

come a long distance, and alone.

Every night we could hear lions roaring, and sometimes the beasts came

walking under the trees in which we slept. This made the gorillas very

angry, and they would shriek and scream and break off branches and throw

them down. They were not afraid of the lions, but they would not descend

to the ground to battle in the darkness.

After the lions had bothered us for many nights I determined to do something

to frighten them away. One afternoon I set out to gather a lot of liana

vines. These vines are as stout as ropes, and some of them are hundreds

of feet long. The gorillas watched me with great curiosity at first, and

then turned in and helped me. When we had twenty long pieces I made slip-nooses

in one end of each and made the other end fast to a branch. When I had

finished, there were twenty vines hanging down so that the nooses touched

the ground.

I was going to try a little trick on the lions. I could not tell the

gorillas my idea, but I am sure they understood. When the nooses had been

prepared and darkness was at hand, I rolled over and over on the ground

so as to leave my scent. No sooner had I begun to roll than the gorillas

did likewise, and we had quite a frolic at it. Then we all climbed up into

the same tree and kept very quiet as we waited.

In about an hour we heard a lion roaring, and fifteen minutes later

he was under the tree sniffing about and growling. He was angered as he

got our scent on the leaves, and as he moved about the vines swung against

him and bothered him. He kept sniffing and growling and prowling around,

and finally something happened. He put his head into one of the nooses,

just as I hoped he would. When the knot tightened on him and he was caught

fast, there was such a roaring of rage and fright as that of the forest

had never heard before. The gorillas knew that the lion had been caught

as well as I did, and they were so excited that they almost fell to the

ground.

In my next adventure I will tell you all about our captive and some

other things of interest.

In my last I told you how I caught a lion by means of a vine with a slip-noose

at the end and how excited the gorillas were over it. Knowing how strong

a lion is, I expected the captive to break away at any moment, but to my

surprise he was held fast. He struggled until he was tired out, and then

after a rest, he began again but the noose held him fast.

All night long he was growling, whining, and thrashing about, and we

got no sleep at all. When daylight came I saw how it was that he had not

got away. He had put his head through one noose, and it had tightened at

the back of his shoulders, and one of his hind legs had been caught in

another. He could not get at the vines with his teeth, and, as I told you,

they were as stout as ropes of that size. If he bad been caught by only

one vine he might have broken it, but he could not break the two.

We had the lion caught fast enough, but he was a savage fellow, and

we knew we must look out for him. The only way we could kill him was with

clubs, so, after looking at him for awhile, we descended the tree and formed

a circle around him. He growled and roared and plunged at us, but every

chance we got we jumped in and gave him a hard blow, and at last he was

finished.

When he was dead the gorillas danced on his body, pulled it about, and

treated it with the utmost contempt. It was finally dragged into the forest

for the jackals to devour.

The gorillas were puzzled to know whether I was a negro boy or one of

themselves, but they thought me very smart and cunning. If we could have

talked together I am sure they would have given me words of praise.

You may wonder if I was satisfied to live with them. Of course I was

not, I wanted to get away and return to my own people, but you must remember

that I was at least forty miles from home, in a strange forest, and if

I had been free to go I should not have known which way to head. But I

was not free. While the gorillas had offered me no harm, I was sure that

if I attempted to escape they would stop me and perhaps kill me. If I went

for food or water some of them always went with me, and I had no doubt

that when I slept at least one was always on the watch over me. I meant

to get away as soon as I could, but I had to wait until a fair chance came.

The gorillas had been traveling at night when they found me tied to a tree,

but from that time I never knew them to be abroad after dark but once.

If they slept in the afternoon they did not go to sloop again until a late

hour at night, but they did not wander far from home.

I had been with them a month when we all set out one morning for a walk

through the forest. We had devoured all the food near our home, and, perhaps,

the gorillas were looking for a fresh supply. We could not talk together,

but I could tell when they wanted me to do anything. As we went through

forest and jungle, some of them walked upright and some on all fours, and

whenever we came to a tree loaded with oranges or guavas we stopped to

eat. Now and then, in the clear spots, we found wild melons growing, and

after eating our fill, we would toss the fruit to each other. We were three

or four miles from our home, and had stopped at a spring to drink, when

I suddenly heard the voices of human beings, and next moment a party of

black men came in sight. What tribe they belonged to I cannot say, but

they had spears and clubs, and were evidently going to fight. They were

twenty in number, and all big, strong fellows. I was for running away at

once, but not so the gorillas. A gorilla fears neither man nor beast, and

is always ready to fight to the death. Our leader uttered a loud "Hu!"

as the negroes came marching on, and the other gorillas scattered about

and armed themselves with clubs. I did likewise.

I think the black men would have run away if they had been let alone,

but the gorillas advanced to the attack, uttering screams of fury, and

in a moment there was a fierce battle raging. I had never fought against

men before, and I was rather frightened at first, but after a bit I was

as savage as any of the gorillas. The negroes fought well, but even with

their spears and outnumbering us twenty to fifteen, they were not a match

for us. Some of the gorillas were wounded, but when we had killed four

of the negroes the others fled in terror, and we let them go.

In my next I shall tell you how I played surgeon to the gorillas, and

how we had fun with an elephant.

When we had gained the victory over the black men, as related in the last

chapter, we set out for home at once; but I carried with me three spears

and the knives belonging to the dead men. Also I took from one or them

a flint and steel to strike fire. I had fought with the gorillas, and fought

well, and they made many signs to show that they were pleased with my conduct.

Four of them had received pretty severe wounds from the spears, and as

soon as we got back to our trees I gathered leaves from a certain bush

and chewed them up and made poultices for the hurts.

Our warriors had always dressed their wounds in this way, but it seemed

that the gorillas had no cures at all beyond plastering on a handful of

mud. They watched me with great curiosity, and when two or three days had

gone by and their wounds had begun to heal I was looked upon with increased

favor. In a week all the injured ones were almost as good as new, and then

I had a trick to show them.

We had left the noosed vines hanging from the trees, and other lions

had come skulking about at night, but they were too sharp to be caught.

One afternoon I killed a jackal with my spear and dragged his bleeding

body around for a quarter of an hour and then left it at the foot of a

tree.

When night came I mounted into the tree with the three spears, each

one of which had a vine tied to the handle. It was not long before the

hyenas came, and from my perch I cast the spears at them and killed three.

Then a lion came roaring and drove them away, and as soon as he was

under the tree I let drive at him and gave him a bad wound. He bounded

away in pain and rage, and half an hour later a second one came.

I hit him at the first throw, but he did not run away. He was foolish

enough to remain and circle around the tree and roar at me, and after missing

him three or four times I cast a spear that entered his side and held him

fast, and in a few minutes he was dead.

Three or four of the gorillas had been in the tree with me to see how

it was done, and from that night on they were ready for anything that came

along.

They could cast the spears further and straighter than I could, and

after a couple of weeks it got so that no wild beast dared come about at

night.

When I first came among them no gorilla could throw a club or stone.

They simply used a club with which to strike.

As soon as they saw me throw they began to imitate, and it wasn't a

week before they could beat me.

Soon after building my nest in the tree I bethought me to make a roof

to keep off the rains and the sun. I made a very good one of sticks and

grass and mud, but hardly had I finished it when every gorilla set to work

and covered his nest in the same way. After getting the knives from the

dead negroes I used them to cut branches and sharpen sticks, and it was

no time at all before my friends could handle them as well as I could.

One day, about three weeks after our battle, an elephant came into our

neighborhood. He was a big fellow and all alone. I was asleep, but one

of the gorillas woke me up and made me understand that something was on

foot.

I went with them, three of us armed with the spears and the rest with

clubs; and pretty soon we found the big beast standing under a tree in

an open space. We crept carefully up on all sides, and all of a sudden

he was stabbed with the spears and beaten with the clubs. He trumpeted

with surprise and rage, and went dashing about; but he might as well have

tried to catch weasels.

After using my spear once, I hid behind the trunk of a tree to look

on.

The way those gorillas bothered that elephant made me laugh loud and

long. While he was chasing one, another would be hanging to his tail, and

two or three would be on his back. They would dodge under his belly, hit

him on the trunk; seize him by the ears and tie vines around his legs,

and at last he became so confused and mad that he charged a big tree and

broke one of his tusks off and rolled on the ground.

The gorillas had no desire to kill him, but they acted like a lot of

jolly boys when out for a good time. They couldn't laugh like human beings,

but they certainly felt like it.

In my next I shall tell you of a journey we took one night and what

happened to us, and I promise to amuse and interest you.

One day, about a week after our sport with the elephant, two of the gorillas

left home and were gone for half a day. Of course, I could not tell where

they went, or what for, but when they returned there was a great jabbering

and chattering, and I understood that something was going to happen. That

evening, instead of climbing to our nests in the trees, we set out through

the forest to the west. I was going to take one of the spears along, but

a gorilla took it from my hand and gave me a club instead. They seemed

to understand that I could not see at night as well as they could, and

one walked on either side of me and gave me his hand.

We walked fast for two hours. We met many hyenas prowling about, and

once a lion roared close to us, but we had no fear of the wild beasts.

By and by we left the forest and jungle behind us, and stood in the open.

I could make out huts and paths, and presently I understood that we were

close to a native village. The people were all asleep in their huts, and

they had no dogs to warn them of our coming. What the gorillas meant to

do I could not guess, but after making sure that no one was awake, we went

ahead until reaching a field of maize. This is the only grain the African

ever sows, and when ripe it is pounded up in a wooden mortar and baked

like hoe cake. There was about an acre of the ripe grain, and the gorillas

began pulling it up by the roots. I worked with them, and in less than

an hour not a stalk was left standing. It was all done out of pure mischief.

When the maize had been destroyed we moved on to a grove of banana trees.

The fruit hung in great bunches on the trees, some ripe and some green,

and we tore down at least three hundred bunches before we stopped. Then

we scattered through the sleeping village and picked up all the cooking

utensils we could find and threw them into a river on the other side.

The gorillas didn't want to kill any one, but they owed the people "a

spite," and took this way of paying it off. When there was nothing more

to be picked up or destroyed, the big gorilla called us all together for

a talk. I can't tell you what he said, but all the others understood it

plain enough. The fifteen of us were divided off so that we stood in front

of five huts. These huts had no doors, and one could look in and see the

people asleep on their grass beds.

When we were ready the big gorilla cried. "Hu! Hu!" and we dashed into

the huts and seized a sleeping man or woman. The three of us got hold of

a big, strong man, and, though he was greatly surprised at thus being attacked,

he kicked and struck and bit and made a good fight of it. We got him out

of the hut, however, and one of the gorillas picked him up and ran to the

bank of the river and flung him in with a great splash. Four other natives

were treated the same way.

By that time the whole village was aroused, and we had to withdraw.

We did not bring away a single article, and I am sure none of the villagers

was hurt. It was just the gorillas' way of having fun.

Three days later a sad thing happened to one of our band. We had been

wandering through the forest when we cams to a large pool of water and

got down to drink. While one of the gorillas was lapping up water a crocodile

rushed upon him and snapped him up. We all saw it, but we had not time

to move a hand before the crocodile had sunk out of sight.

The gorillas were thrown into a great rage and wanted revenge, but they

did not know how to get it until I showed them the way. I cut several vines

and made slipnooses, as I had to catch the lion, and then I had the gorillas

go back to the water and pretend to be drinking. It was not long before

another crocodile rushed out, but they were on the watch, and darted away,

and while he rested on the bank, wondering where his dinner had gone to,

I threw three of the slipnooses over his head. Then we all got hold and

drew him far from the water, and when we had beaten him with clubs, we

made him fast to a tree and left him to die. The gorillas felt the loss

of their companion very much, and for three or four days there was no frisking

about.

In my next, which will be the end of the story, I shall tell you all

about how I escaped from the gorillas and got among white people.

You may think I was satisfied to stay with the gorillas, as they had treated

me well and it was a pleasant life, but from the very first day I was always

longing to get away and back to my own people.

The trouble was that they never let me out of their sight for a moment.

Many and many a time I started out to take a little walk by myself, hopeful

for a chance to get away, but one or more of the animals always followed

me, and if I walked too far they grew angry.

It was plain that they meant to keep me a prisoner, and if they caught

me trying to escape it would be bad for me.

In telling you of the battle we had with the black men I told you of

finding a flint and steel after the fight was over. I knew how to strike

a spark and build a fire, but I put the things away in a hollow tree and

made no use of them. I had a plan in my head to use them later on, but

I must first know where I was, and how far it was to my village.

I was always in hopes that we should set out some day and journey toward

the Zambesi River, and that, finding myself near home, I might get away

by day or night, but we never went in that direction.

It seemed as if the gorillas suspected me, and wove determined not to

give me a chance.

When I had been a prisoner for three long months and had become discouraged,

I determined to try my plan. I knew that all wild animals were afraid of

fire, but I could not tell just how frightened the gorillas would become

on seeing flames. If they did not run far away then my plan would be a

failure.

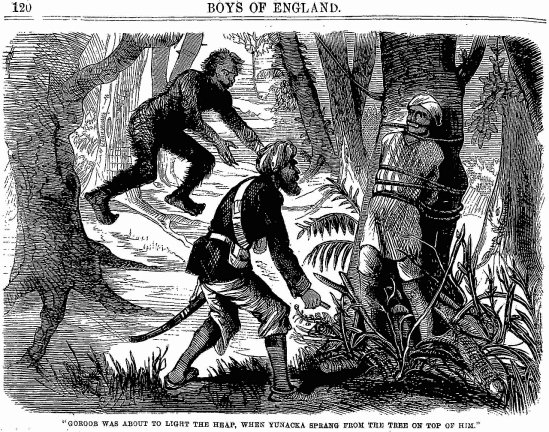

One day about noon, when there was a pretty stiff breeze blowing, I

began piling up a great heap of dead leaves and limbs. The gorillas were

very curious to know what I intended to do, and they watched me very closely.

When I brought out the flint and steel they gathered around me like a lot

of schoolboys, and when I struck fire they all cried out: "Hu!" and scampered

around in sport.

In a minute the leaves begun to blaze, and as the smoke and flames leaped

up my friends began to chatter and scream and draw away. The wind carried

the flames into the thick forest, and pretty soon there was a fire raging

that a hundred engines could not have put out;

The gorillas huddled around me for three or four minutes, afraid of

the flames, but not wishing to leave me, but at last terror overcame them,

and they ran screaming away.

Instead of following them, I ran in another direction, and I had gone

as many as ten miles before I felt safe from pursuit.

I had a fear of meeting, black men or other gorillas, but fortunately

I did not.

All that afternoon and for three days more I journeyed through the forest,

sleeping in trees at night, and then I came upon a party of white men camped

in a grove.

They were traders who went from tribe to tribe selling spearheads, knives,

looking-glasses, beads, and other things. Two of them had been in our village,

once, and I knew them at sight.

"When I had told them my story they said it was a wonderful one, and

then they told me that my father and all my tribe believed that I had been

put to death by the Makololos.

I was too far from home to think of going back alone, and the traders

advised me to go with them to Cape Town, and live among the white people

for a time.

I was glad to go with them, and scarcely had we come to the towns and

cities when the people began to question me and declare that my adventures

were wonderful.

The newspapers said that I was the only person ever heard of who had

been captured by gorillas and got away alive.

One day a dime museum man came to see me, and after a little talk, he

offered me money to go to England with him and be put on exhibition as

the Gorilla Boy.

I consented to go, and have been traveling about ever since. I am now

about sixteen years old, and have visited many countries and seen many

strange things.

I am no longer a savage, but I dress and live like any white boy. and

I can also speak very good English.

Of course, I should like to see my father and mother and my native village

again, but they are a long way off, and there are many dangers in the way.

The Mwais would be glad to see me, and I could tell them many wonderful

things I have seen since I left them; but I do not think they would be

pleased at my wearing clothes and eating the food of white men.

Should I ever go back to them, I will remember the readers of this story,

and write my further adventures for them.

THE END

Completed September, 5, 2007

Comments/report typos to

Georges Dodds

and

Bill Hillman

BACK

TO COVER PAGE

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL &

SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

©Copyright

2008 Georges T. Dodds

All

other Original Work ©1996-2008 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.