Volume 1832

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/hermit.htm

| Preface. | |

| Alternate Preface. | |

| Dedication. | |

| On the Hermit's Solitude. | |

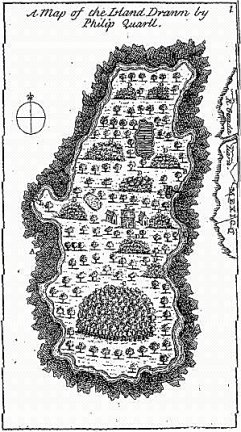

| Explanation of the Map. | |

| Book I. | An account how Mr. Quarll was found out, with a description of his dress, habitation, and utensils; as also, his conversation with the persons who first discovered him. |

| Book II. | An account of the birth and education of Philip Quarll; as also the most surprising transactions of his life, from his infancy to his being cast away. Taken from the memoirs he gave to Mr. Edward Dorrington, the person who found him on the island. |

| Book III. | An account how Quarll's wonderful shifts, and surprising manner of living; of the miraculous acts of Providence, and of the strange events which happened in the island since his being there. |

Now it may, without the least arrogance, be affirmed, that, though this surprising narrative be not so replete with vulgar stories as the former, or so interspersed with a satirical vein, as the last of the abovementioned treatises; yet it is certainly of more use to the public, than either of them, because every incident, herein related, is real matter of fact. But because my share in this work, is no other than that of a bare editor; I think it my duty to account for the possession of this manuscript.

It was put into my hands, about a year ago, by Mr. Dorrington, an eminent merchant, with full liberty to publish it when, and in what manner, I thought most proper. I hope therefore it will not be deemed impertinent to give some account of my friend, as a reputation to the work itself.

"Mr. Edward Dorrington is descended from a very ancient and honourable family in Staffordshire. His grandfather, Mr. Joseph Dorrington, removed out of that county, to Frome in Somersetshire; his employ was that of a very considerable grasier: the issue he left at his decease was one son, Richard (the father of my friend) and two daughters. Mr. Richard Dorrington for some time, was a student of Gray's-Inn; but, liking a country-life best, he having thoroughly qualified himself, retired to Frome, the abovementioned residence of his father, where he married Mrs. Margaret Groves, of Taunton, a gentlewoman of about a thousand pounds' fortune. Soon after his marriage, he went and settled at Bath, where the integrity of his fair practice, soon rendered him eminent in his profession. He acquired a very competent estate, and died in the year 1708, having no other issue than his only son, the present Mr. Edward Dorrington, whom he had put to be bred a merchant, under the care of Mr. Stephen Graham of Bristol. His diligence, and courteous behaviour, during his servitude, so highly recommended him to his master's esteem, that when his time was expired, he admitted him into a moiety of his commerce, married him to his daughter, and gave her a handsome portion suitable to his merit.

The happiness of my acquaintance with him, began in his apprenticeship, and has, with the greatest satisfaction to me continued ever since." As to the genuineness of this treatise, I am farther to assure the reader, that as Mr. Dorrington is allowed by all who know him, to be a gentleman of unquestionable veracity, and above attempting an imposition upon the public; so the first book herein was wholly written by himself, and the second and third books were faithfully transcribed from Mr. Quarll's parchment roll, which was a continuation of what my friend had begun.

When Mr. Dorrington undertook this voyage, he set sail, as is well known, from Bristol to the South-sea, and traded all along that coast to Mexico, now called New-Spain.

And he is now making a second voyage to the same places.

To proceed to the work itself. The first book contains a relation of Mr. Dorrington's discovery of Mr. Quarll, his several conferences with him, a description of the island, and the manner of our hermit's living there; with many other curious particulars.

The second and third books are the contents of the hermit's parchment-roll above-mentioned, and contain the most surprising, as well as various turns of fortune ever yet recounted in any work of this kind. and, although the continued series of misfortunes which attended him, seemed to render his life a precedent of the most unhappy state of human nature; yet we do not find the greatest notoriety in his actions, that vengeance should pursue him so closely by unparalleled crosses. If polygamy could call down such divine resentments, we must be silent; nor farther urge his fate.

However, for this fact he was brought to justice by the laws of his country, and he accounts for the inducements of his committing that sin, at his trial. This reflection therefore should be wiped off, since he is now become the humblest of penitents. The observations throughout these sheets will be found to be modest, serious, and instructive, and all centre in the unerring moral, that,

Whatever we do, or wheresoever we are driven, Still, we must own such is the will of Heaven.To conclude, in the publication of these papers, I have discharged two promises; the one made by Mr. Dorrington, to the hermit, and the other made by myself to Mr. Dorrington; and that they may meet with a reception, as candid as they are useful, is the hearty wish of the reader's humble servant.

Having written and published the following history, I fulfil the old gentleman's injunction to my friend when he gave him the memoirs out of which I have taken it, and his promise at the receiving thereof. I must confess when I first undertook the task, I had but little encouragement to go on with the work, the booksellers shops being already crowded with Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, Colln. Jacks, and numbers of that nature, but they having had their admirers, it may be hoped that though this surprising narrative be not so replete with vulgar stories, or so interspersed with a satirical strain as the above said, it may be accounted as useful as either, the incidents therein mentioned being neither supernatural, fabulous nor romantic, but diverting and moral; I therefore dare depend that the reader will not think his time ill bestowed no more than I did mine in fulfilling my friend's promise to the good old requester, that his works should be published, who has taken the pains to make a research of all the transactions of his life for 70 years past, with that most pious intent being not only to take up some of the anxious time his solitude did occasion, but chiefly to excite his devotion and rouse his gratitude to a due sense of the many favours, unaccountable mercies that have been so liberally and often extended upon him, throughout the whole course of his life, which has sundry times been rescued by kind Providence from apparently unavoidable perils and dangers, as though decreed by fate to a predestined ruin; and then, that if his memoirs should after his decease happen to fall into anybody's hands, they might be an emulation to virtue and an encouragement to the unfortunate and distressed, never to despair though in the greatest of extremity.

These devout and religious motives being what prompted that good man to so pious a work well deserve my labour in recording his memory, and as his personal merits were the principal occasion of several of the most material transactions which compose this treatise. I have as near as I could done them justice still keeping to my original as much as the making it a complete history will permit, without affectation of lofty phrases or smooth expression as usual in novels and romances, the subject having merit enough of itself to recommend it.

Therefore having in a plain manner performed my undertaking. I leave the venerable hermit, in full enjoyment of happiness and his reader the pleasure of tracing his steps, along the serpentine and winding lane that lead him thither, whilst I wait my friend's return, who promised to endeavour seeing the old man again if those dangers, who forbid the very attempt thereof are but once absent and then I will by the means of some honest bookseller impart to the public whatever I shall have heard of him.

N.B. The bookseller who purchased my copy, having in his preface, made one Mr. Dorrington, a pretended Bristol merchant on whom he fathers a journal at the end of my first book to be the author of the present history, in order to advance the sale of his books, this is to certify that I never knew no such a person, least anyone be displeased at the imposition.

Having the good fortune to hit on a subject as uncommon as agreeable, I have employed some of the anxious hours the irksomeness the tedious confinement my indisposition has put me to these six years, in writing the following history, which though short, contains many wonderful and surprising transactions happened in the space of seventy years to one whose ruin a cross and averse fortune seemed to have unavoidably determined, but most miraculously averted by Providence, as often as it appeared at hand.

The account whereof being not only most agreeably surprising, but also morally diverting, I have taken pleasure in giving a relation thereof, and hope your honour will take the same in the perusal of it, which emboldens me to offer it unto you, hoping that as the venerable old man, the hero or the following history is the first churchman of his nation, as embraced a hermit's life. Severing himself so voluntarily from the world, freely abandoning all reliance on human assistance, wholly depending and faithfully trusting on Providence, being also endued by nature and timely education, with some of those virtues as shine so bright in your honour, and warmed with that love and zeal for the church, the king and his country, as inflames your noble and loyal breast, he seems to have a title to crave your protection, which is the favour I beg, and which I hope your honour will not refuse, being he has made atonement for all past faults, fully applying his life to the practice of piety and religion, which your worthy ancestors and yourself have ever been protectors and encouragers of.

And now he has with unparalleled patience and true Britain's courage withstood the severest shocks of averse fortune, run thorough a long series of the most malignant influences it could launch out, his blooming years and early days being chequered and darkened with many black and sullen hours, I at last saw him rush thorough a hundred glaring perils, and happily arrive to the quiet and inestimable enjoyment of content, a happiness which I heartily wish your honour and posterity, as being most sincerely

A. The place where the hermit was cast away.

B. The place where Mr. Dorrington landed.

C. The wood, about three quarters of a mile cross.

D. Clusters of trees proceeding from one stem.

E. The hermit's lodge.

F. Enclosed ground, where he sets pease and beans.

G. A fountain that issues out of the rock,

H. The basin wherein it runs.

I. The pond 200 yards long, and about 100 broad.

K. The lake between the rock and the Island,

L. The cavity in the rock, where the hermit goes to worship.

Having concluded those mercantile affairs, which I undertook, by this voyage, to negotiate; and being upon my. return for England, and wind-bound; during my stay, I daily walked about the sea-shore: very early one morning, the weather being extreme fair, and the sea wonderful calm, as I was taking my usual turn, I accidentally fell into discourse with a Spanish, Mexican Inhabitant, named Alvarado. And, as we were viewing the rocks which abound in those seas, he desired me to take notice of a vast long one about seven leagues from shore, which he said was supposed to enclose some land, by its great extent; but the access to it was very dangerous, by reason of the rocks which reach so far under water, being in some places too shallow for boats, and in others too deep to ford over, and the sea commonly very rough in that place, hitherto prevented farther research, supposing the advantage which might accrue from the land, would not countervail the cost and trouble of making it inhabitable; for that he and some friends had on a fine day, & it now was, the curiosity to go as near as any could with safety, which was above fifty yards from the main rock, but were forced to return as unsatisfied as they went; only, that he had the pleasure of catching some delicious fish which lay playing upon the surface of the water, having a rod in his hand, and lines in his pocket, being seldom without when he walks on the seashore; these fish are somewhat larger than a herring in its prime, skinned like a mackerel, made as a gudgeon, and of divers beautiful colours, especially if caught on a fair day, having since observed that they are more or less beautiful, according to the serenity of the weather.

The account he gave me of them excited my curiosity to go and catch some, and he being, as usual, provided with tackle, we picked up a parcel of yellow maggots, which breed in dead tortoises upon the rock, at which those fishes bite very eagerly.

Thus equipped with all necessaries for the sport, we agreed with a young fellow, one of the long-boat's-crew, belonging to the ship I was to come over in, whose master being just come on shore, and not expected to return speedily, he readily consented to row us thither for about the value of a shilling.

Being come to the place, we found extraordinary sport, the fishes were so eager, that our line was no sooner in but we had a bite.

Whilst we were fishing, the young man that rowed us thither, spying a cleft in the rock, through which he saw a light, had a mind to see what was at the other side; so put off his clothes in order to wade to it, thus having taken the hitcher of the boat, he gropes along for sure footing, the rock being very full of holes.

Being come to the cliff, he creeps through, and a short time returns, calling to us with precipitation, which expressed both joy and surprise: "Gentlemen! Gentlemen!" said he, "I have made a discovery of a new land, and the finest that the sun did ever shine on; leave off your fishing, you'll find here much better business." Having by that time caught a pretty handsome dish of fish, we put up our tackling, fastened our boat to the rock, and so went to see this new-found land.

Being come at the other side of the rock, we saw, as he said, a most delightful country, but despaired going to it, there being a lake about a mile long, at the bottom of the rock, which parted it from the land; for neither Alvarado nor myself could swim; but the young fellow who could, having leaped into the water, finding it all the way but breast high, we went in also, and waded to the other side, which ascended gently, about five or six foot from the lake to a most pleasant land, flat and level, covered with a curious grass, something like camomile, but of no smell, and of an agreeable taste; it bore also abundance of fine lofty trees, of different kinds and make, which in several places stood clusters, composing groves of different height and largeness: being come to a place where the trees stood in such a disposition as gave our sight a greater scope, we saw at some distance a most delightful wood of a considerable extent. The agreeableness of the perspective, made by Nature, both for the creating pleasure and condolence of grief, did prompt my curiosity to a view of the delights, which the distance we were at might in some measure rob us of: but Alvarado, who, till then, had discerned nothing whereby we could judge the island to be inhabited, was fearful, and would not venture farther that way, lest we should of a sudden be sallied upon by wild beasts out of the wood and, as I could not discommend his precaution, the thickness of it giving room to believe, there might be dangerous creatures in it, so we went southward, finding numbers of fine trees, and here and there small groves, which we judged to be composed of forty or fifty several trees; but, upon examination, we found it, to our great amazement, to proceed of only one plant, whose outmost lower branches bending to the ground, about seven or eight foot from the middle stem, struck root, and became plants, which did the same, and in that manner covered a considerable spot of ground, still growing less, as they stood farthest from the old body.

Having walked some time under that most surprising and wonderful plant, admiring the greatness of Nature's works, we went on, finding several of the same in our way, wherein harboured monkeys, but their swift flight prevented our discerning their colours; yet going on we found there were two kinds, the one green backs, yellow faces and bellies, the other grey, with white bellies and faces; but both sorts exceeding beautiful.

At some distance we perceived three things standing together, which I took to be houses; "I believe," said I, "this Island is inhabited; for, if I mistake not, yonder are dwellings:" "So they be," said Alvarado, "and therefore I don't think it wisdom to venture any further, lest they should be savages, and do us hurt;" so would have gone back; but I was resolved to see what they were, and persuaded him to go on, saying, it would be time enough for us to retreat when we perceived danger: "that may be too late," said he, "for, as evil does not always succeed danger, danger does not always precede evil; we may be surprised." "Well, well," said I, "if any should come upon us we must see them at some distance, and if we can't avoid them, here's three of us, a good long staff, with an iron point at one end, and a hook at the other, I shall exercise that, and keep them off, at least till you get away; come along, and fear not," so pulled him along.

Being come near enough to discern better, we found what we took for houses were rather arbours, being apparently made of green trees, then indeed I began to fancy some wild people did inhabit them, and doubted whether safe or no to go nearer, but concealed my doubt lest I should intimidate Alvarado, so that he should run away, to which he was very much inclined. I only slackened my pace, which Alvarado perceiving, imagined that I saw some evil a coming, which he thought unavoidable; and not daring to go from his company, I only condoled his misfortune, saying, he dearly repented taking my advice, that he feared we should pay dear for our silly curiosity; for indeed those things were more like thieves' dens, or wild people's huts, than Christians' habitations.

By this time we were come near a spot of ground, pretty clear of trees, on which some animals were feeding, which I took to be goats; but Alvarado fancied them to be deer, by their swift flight at our appearing; however I inferred by their shyness that we were out of the way in our judgment concerning the arbours; "for," said I, "if these were inhabited, those creatures would not have been so scared at the sight of men; and, if by nature wild, they would not graze so near men's habitations, had there been anybody in them. I rather believe some hermit has formerly lived there, and is either dead or gone." Alvarado, who to that time had neither heard nor seen anything that could contradict what I said, began to acquiesce to it, and goes on.

Being come within reach of plain discernment, we were surprised; "if these," said I, "be the works of savages, they far exceed our expert artists;" there regularity appeared unconfined to the rules of art, and complete architecture without the craft of the artist, Nature and time only being capable to bring them to that perfection. They were neither houses, huts, nor arbours, yet had all the usefulness and agreements of each.

Having sufficiently admired the uncommon beauty of the outsides, without interruption, but rather diverted with the most agreeable harmony of various singing-birds, as perched on a green hedge, which surrounded about one acre of land near the place, we had the curiosity to see the inside, and being nearest the middle- most, we examined that first, it was about nine foot high, and as much square, the walls very straight and smooth, covered with green leaves, something like those of a mulberry-tree, lying as close and regular as slates on a slated house, the top went up rounding like a cupola, and covered in the same manner as the sides; from each corner issued a straight stem, about twelve foot higher, bare of branches to the top, which were very full of leaves, and did spread over, making most pleasant canopy to the mansion beneath.

Being full of admiration with the wonderful structure, and nature of the place, we came to a door which was made of green twigs, neatly woven, and fastened with a small stick, through a loop made of the same.

The door being fastened without, gave us encouragement to venture in it, being evident that the host was absent; so we opened it, and the first thing we saw, being opposite to the door, was a bed lying on the ground, which was a hard dry hearth, very smooth and clean; we had the curiosity to examine what it was made of, and found it another subject of admiration; the covering was a mat about three inches thick, made of a sort of grass, which, though as dry as the oldest hay, was as green as a leek, felt as soft as cotton, and was as warm as wool; the bed was made of the same, and in the same manner, but three times as thick again, which made it as easy as a down bed; under that lay another, but something harder.

At one side of the room stood a table made of two pieces of thin oak board, about three foot long, fastened upon four sticks driven into the ground, and by it a chair made of green twigs as the door, at the other side of the room lay a chest on the ground like a sailor's small chest, over it, against the wall, hung a linen jacket and breeches, as seamen wear on board; on another pin hung a large coat or gown, made of the same sort of grass, and after the same manner as the bed's covering, but not above half an inch thick, and a cap by it of the same; these we supposed to be a winter-garb for somebody.

Having viewed the furniture of the dwelling, we examined its fabric, which we could not find out by the outside being so closely covered with leaves; but the inside being bare, we found it to be several trees, whole bodies met close, and made a solid wall, which, by the breadth of every stem, we judged to be about six inches thick, their bark being very smooth, and of a pleasant olive-colour, made a mighty agreeable wainscoting; the roof, which was hung very thick with leaves, was branches, which reached from end to end, and were crossed over by the side-ones that were woven between, which made a very even and, so thick of leaves and branches, that no rain could penetrate. My companion's uneasiness, expecting the host's return every moment, hindered my examining every thing more narrowly. and having slightly looked into the chest, which lay open, wherein we saw nothing but sheets of parchment, which his haste would not permit me to look into; we went away.

Going out, we saw at one corner of the room behind the door a couple of firelocks, the sight of which much alarmed my company; and, I must confess, startled me; for, till then, I was inclinable to believe some hermit did dwell in the place; but finding arms in the room of a crucifix and religious pictures, which are the common ornaments of those religious men, made me waver in my opinion; and having taken the pieces in my hands, which for rust appeared not to have been fit for use for many years, renewed my former opinion, supposing them to be the effects of some shipwreck which the hermit found upon the rocks; but my company persisting in their own, hastened out, and would have gone quite away, without seeing any more, had I not, by many arguments made them sensible, that if those arms had been intended for the evil use he did imagine, they would have been kept in better order; to which being obliged to acquiesce, he consented to go and examine the other, being as worthy of admiration as that we had seen, though quite of another nature, but much of the same height and make.

The next we came at was covered all over with the same sort of grass as grew on the ground, which lay as even as though it had been mowed and rolled; behind it were several lodges, made, as it were, for some dogs, but we neither saw nor heard any.

Having viewed the place all round, we placed the young fellow with us at the outside to give notice when anybody appeared, least we should be surprised, whilst we saw the inside. So having opened the door, which was made and fastened after the manner of the first; we went in, expecting to find another dwelling, but it proved rather a kitchen, there being no bed, only a parcel of shells of different sizes, which we supposed to be used for utensils; some being callowed at the outside, as having been on the fire, but extreme clean within, the rest were, both inside and outside, as fine as nakes of pearl.

At one end of the room was a hole cut in the ground like stew-stoves in great kitchens, about three or four foot from that there was another fireplace, made of three stones fit to roast at, in both which places appeared to have been fire lately by wood-coals and ashes fresh made. This confirmed my opinion, that it was an hermitage: Alvarado, who all along feared we should meet with men as would misuse us, was not a little pleased to find fireplaces in room of beds, and kitchen-utensils instead of weapons. "I hope," said he, "we are not in so great a danger as I feared, here cannot be many men, unless they crowd together in yonder place; and if so they would have been here before now, had they been in the way." His fears being in a great measure dispersed, we looked about more leisurely, and seeing several shells, that were covered, on a shelf that lay cross two sticks, that were stuck in the wall, which was made of turf, we had the curiosity to see what was in them, and found in one pickled anchovies, in others mushrooms, capers, and other sorts of pickles: "let them," said I, "be who they will that dwell here, I am sure they know good eating, and therefore probably may be no stranger to good manners." Upon another shelf, behind the door, lay diverse sorts of dried fishes, and upon the ground stood uncovered two chests with fish and flesh in salt.

These provisions being something too epicurial for an hermit, gave us room for speculation. "I have lived," said Alvarado, "at Mexico these six years, and have been at Peru above twenty times, and yet never heard talk of this island: the access to it is so difficult and dangerous, that I dare say we are the first that have been of these sides of the rocks; I am very apt to believe that a company of determinate buccaneers, which are said to frequent these seas, shelter here, and that the habitation we have seen, and this place, belong to their captain, and that the company resorts in caves up and down these rocks." Really I could not well gainsay it, being too probable, yet I would not altogether acquiesce to his opinion, lest he should thereby take a motive to go away before we had seen the other place: "I must confess," said I, "here's room for conjectures, but no proof of certainty; however let it be as you say, 'tis a plain case here be none to disturb us, therefore whilst we have liberty, let us see the other place." So we fastened the door as we found it, and went to the next, which was shut after the same manner as the two preceding, but made of quite different stuff, being a complete arbour, composed of trees, planted within a foot of one another, whole branches, were woven together in that regular manner, that they made several agreeable compartments, and so close, that nothing but air could enter; it was of the same height and bigness with the kitchen, which stood at the other end of the dwelling, which made a very uniform wing to it.

The coolness of the arbour removed our doubts of its being another dwelling, unless only used in hot weather.

Having sufficiently viewed the outside, we went in, and found several boards, like dressers or tables, in a pantry, on which lay divers broad and deep shells, as beautiful as those in the kitchen, in some of which was butter, in others cream and milk; on a shelf lay several small cheeses, and on another a parcel of roots like Jerusalem artichokes, which looked to have been roasted: all this did but confirm the opinion we were in, that it was no hermitage, there being what to gratify the appetite, as well as to support Nature; therefore, not knowing what to think of the master of the house, we made no long stay, but concluded to haste, and get our fish dressed, it being near dinner-time; and as the trees stood very thick inland, so might conceal men from our sight, till come too near to shun them; we thought it proper to walk at the outside near the rocks, that we might see some distance before us.

Walking along, a phlegm sticking in my throat, I happened to hawk pretty loud, the noise was answered from, I believe, twenty places of the rock, and in as many different sounds, which so alarmed Alvarado, who took it to be a signal from men concealed up and down the rock, not considering the difficulty of their coming at us, there being a lake at the foot of it, which they must have been obliged to wade over, and which would have given us time to get away : but fear, which often binds reason, did represent the evil infallible to his thought, which was morally impossible. I did all I could to make him sensible it was but echoes, and to convince him thereof, I gave a loud hem, which was answered in like manner, but by being a second time repeated, and by a louder voice, I was certain the last did not proceed from me, which put me in apprehension some body besides myself had hemed also. My companion, whose countenance being turned as pale as death, expressed the excess of his fears, would have run away, had not the voice come from the very way we were to go: "now," said he (hardly able to utter his words for trembling) "you are, I hope, convinced it would have been safer for us to retire, instead of gratifying your unreasonable curiosity, what do you think will become of us?" the young fellow at these words falls a weeping, saying, he wished he had missed the getting of that money, which was like to be dearly earned. I must confess, I begun to be a little apprehensive of danger, and wished myself safe away, but concealed my thoughts, heartening them as well as I could, and representing the danger equal, moving forwards or standing still; I at last persuaded them to go on.

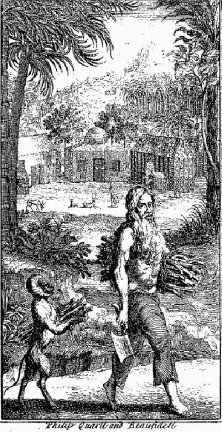

We were scarce gone forty paces further, but that we perceived at a considerable distance something like a man, with another creature, but presently lost them amongst the trees, before we could have a full view of them, which made every one of us conceive a different idea of what we had seen. Alvarado would have it to be a giant, and a man of common size with him, and both armed cap-a-pee. The poor lad, who was already as bad as a slave, being bound to a severe ill-natured master, feared death more than bondage, so took what he had seen for some she-bear, and one of her whelps with her, to make her yet more dreadful; and by all means would have thrown himself into the lake, in order to get at the other side of the rock; thus the danger appeared to each of them to be what they dreaded most; but I was something better composed in mind than they. I gave the object I saw the likeliest resemblance the time it was in sight did permit, which I could adapt to nothing but a man of common size, and something like a dog with him; so persisting in my opinion made them waver theirs; thus we went on something better composed.

Being gone about an hundred yards further, we saw the same again, but nearer hand, and without interruption, the place being pretty clear of trees; thus having a full view, we were all, to our great satisfaction, convinced, that what had been taken for a formidable giant, and a terrible she-bear, was but an ordinary man; but that which was with him running up a tree as soon as he perceived us, prevented our discerning what animal it was; but the man, who walked on a-pace, soon came within the reach of a more certain discernment, and appeared to be a venerable old man, with a worshipful white beard, which covered his naked breast; and a long head of hair of the same colour, which, spreading over his shoulders, hung down to his loins.

His presence, which inspired respect more than fear, soon repealed the frightened folks scared senses, who, to cover this faint-heartedness, excused themselves by the misrepresentations distance causes on objects. The old man, who by that time was come near enough to discern our speaking English, lets fall a bundle of sticks, he had under one arm, and a hatchet he carried in the other hand, and runs at me, being the next to him, embracing me, saying, "dear countrymen, for I hear ye are English, by what accident are ye come here; a place the approach, whereof is defended by a thousand perils and dangers, and not to be come at but by a narrow escape of death, are ye shipwrecked?"

"No, thank god," said I, "most reverend father, it was mere curiosity that brought us here, those perils, which you say defend the approach of this Island, being absent by the extraordinary calmness of the sea; but if I may ask, pray how came you here?"

"By the help of Providence," replied the good old man, "who snatched me from out of the ravenous jaws of death, to fix me in this safe and peaceable spot of land; I was shipwrecked, thanks to my maker, and was saved by being cast away."

"I conceive, sir," said I, "you have been chased by some pirates, and escaped slavery by striking upon the rocks that surround this island; but now you have avoided that dismal fate, embrace the lucky opportunity of getting away from a place so remote from human assistance, which your age makes you stand in need of."

"That's your mistake," replied the old man, "he who trusts in God needs no other help."

"I allow that, sir," said I, "but our trust in God doth not require us to cast away, or despise the help of man. I don't in the least question your piety, but mistrust the frailty of nature, and debility of age, therefore would have you come and live within the reach of attendance; you may, without slackening your devotion, live in the world; you shall have no occasion to concern yourself with any cares that may disturb your pious thoughts."

"No," replied the old man, "was I to be made emperor of the

universe, I would not be concerned with the world again, nor would you require me, did you but know the happiness I enjoy out of it; come along with me, and if, after you have seen how I live here, you persist in your advice, I will say you have no notion of a happy life."

"I have, good sir," said I, "already seen with great admiration your matchless habitation, but there are other necessaries which your age requires, as clothes to defend the injuries of the air, and meat suitable to the weakness of your stomach."

"That's your mistake," replied the old man, "I want for no clothes, I have a change for every season of the year, I am not confined to fashions, but suit my own conveniences. Now this is my summer dress, I put on warmer as the weather grows colder; and for meat, I have fish, flesh and fowls, and as choice as man can wish for; come, you shall dine with me, and ten to one but I may give you a venison, and perhaps a dish of wild fowls too; let's go and see what Providence has sent us."

So we went to a wood, about a mile further, where he had fastened several low nets at different gaps in the thick-set, in one of which happened to be an animal, something like a fawn as big again as a hare, and the colour of a fox, faced and footed like a goat: "did I not tell you," said the good man, "I might chance to give you venison? now let's look after the fowls;" so we went a little further at a place where he had hung a long net between two high trees, at the bottom of which was fastened a bag of the same to receive the fowls, who in the night being stopped by the net, fluttered to the bottom. There also happened to be game, a couple of fowls made like wood-cock, but the bigness and colour of a pheasant, were taken at the bottom of the bag:

"Now," said the old man, "these I have without committing the sin of bidding less for them than I know they are really worth, or make the poulterers swear they cost them more than they did. Well, now I may give you a dish of fish also, 'tis but going half a mile, or thereabouts."

"There's no need, sir," said I, "for any more, there's but four of us, and here's provision for half a score; but if you are disposed for fish, we have some in a boat at the other side of the rock; 'tis but going for them."

"Very well," said the old man, "'tis but going above a mile, then strip and wade over a lake, then climb up a rugged rock twice backward and forward to fetch what we can have for only taking a pleasant walk, all the while diverted with the sweet harmony of a number of fine birds; look here, this complaisance often puts men to a world of needless trouble. Come, we'll make shift to pick a dinner out of these."

"Sir, said I, "'tis no shift where there's such plenty."

"Plenty!" said the old man, "why I tell you this is a second garden of Eden, only here's no forbidden fruit, nor women to tempt a man."

"I see, sir," said I, "Providence supplies you plentifully with necessaries, did not age deprive you of strength."

"Age!" replied the old man, "why I'm not so old as that comes to neither; I was but eight and twenty when I was cast away, and that's but fifty years ago: Indeed if I did live as you do that dwell in the wife world, who hurry on your days as if your end came on too slow, I might be accounted old."

"I don't gainsay, reverend father, but that you bear your age wonderful well; but multiplicity of days must make the strongest nature bend: yes, time will break the toughest constitution, and by what you say you have seen a considerable number of years."

"Yes," replied the old man, "a few days have ran over my head, but I never strove to out-run them, as they do that live too fast: well," says he, "you are a young man, and have seen less days than I, yet you may be almost worn out; come, match this," says he; with that he gave a hem with such a strength and clearness, that the sound made my ears tingle for some minutes after.

"Indeed, sir," said I, "you have so far out-done what I can pretend to do, that I will not presume to imitate you."

"Then I am afraid," says he, "you will prove to be the old man. Well then, you or your friend, the strongest of you, fetch hither that stone, it does not look to be very heavy" (pointing at a large stone that lay about two yards off.)

"I'll endeavour, sir," said I, "to roll it, for I dare say 'tis past my strength to lift it:" so, to please the old man, I went to take it up, but could hardly move it.

"Come, come," said the old gentleman, "I find that must be work for me;" with that he goes, takes up the stone, and tosses it to the place he bid me bring it: "I see," said he, "you have exerted your strength too often, makes you now so weak: well, you see the advantage of living remote from the world; had you had less of human assistance, I am apt to believe you would not want it so soon as you are likely to do; come, let's make much of that little strength we have left, by taking necessary support at proper times; 'tis now past noon, therefore let's lose no time, but haste home to get our dinner ready;" so we went back to the place where the bundle of sticks lay, which we made the young fellow with us to carry, and went directly to the kitchen, where, whilst he made a fire, one cast the animal, and the other two pulled the fowls.

"I am sorry,' said the old man, "you must take that trouble, but your pretence has frightened away my servant, who used to do that work for me."

"Have you a servant then, sir?" said I.

"Yes," said he, "and one a native of this island.

"Then, I find, sir," said I, "this island is inhabited."

"Yes," answered the old man, "with monkeys and myself, but nobody else, thank god; otherwise, I can tell you, I should hardly have lived so long."

"Then, sir," said I, "I suppose that was it we saw run up a tree."

"Yes," said he, "my monkey, like myself, love not much company."

"Pray, sir," said I, "how did you bring him so well under command, as to keep with you, when he has liberty to run away? I wonder the wild ones do not entice him from you."

"I had him young," replied the old man, "and made very much of him, which those creatures dearly love; besides, when he was grown up the wild ones would not suffer him amongst them; so that he was forced to remain with me. I had another before this; but him, I may say, was lent by Providence, both to be a help and diversion to me; for he was so knowing, that he took a great deal of labour off my hands, and dispersed many anxious hours, the irksomeness of my solitude did create; 'tis now about twelve years since, for I keep a memorial, which indeed I designed to have been a journal, but I unfortunately let the regular order of the days slip out of my memory, however I observe a seventh day, and reckon the years from winter to winter, so I cannot well mistake.

"One day that I had roasted a quantity of roots, which I eat instead of bread, having spread them on my table and chest to cool, in order to lay them by for use, I went out, leaving my door open to let the air in.

"Having walked an hour or two I returned home, where I found a monkey, whom the smell of the hot roots had brought, who, during my absence, had been eating: my presence very much surprised him, yet he still kept his place, only discontinued eating, staring me in the face. the unexpected guest at once startled me, and filled me with admiration; for certainly no creature of its kind could be compared to it for beauty; his back was of a lively green, his face and belly of a lively yellow, his coat all over shining like burnished gold: the extraordinary beauty of the creature raised in me an ardent desire to keep him, but despaired of ever making him tame, being come to its full growth; therefore having resolved to keep him tied, I went in and shut the door; the beast, who till then had not offered to make his escape, appeared very much disturbed, and stared about him for some place to get out at; perceiving his disorder, I did not advance, but turned my back to him, to give it time to compose itself, which he, in a short time, did, as appeared by his falling to eat again, which made me conceive hopes, that I would in time make him familiar; having about me stale roasted roots, which eat much pleasanter than the fresh, and are less stuffing, I threw some at him, at which he seemed displeased, and stood still a while, staring in my face; but my looking well pleased, which I believe the animal was sensible of, made him pick them up, and fall to eating with a fresh appetite. I was overjoyed at his easy composure, so reached him water in a shell, that the want of nothing might induce him to a retreat, I set it down as near him as I could without disturbing him, he came to it very orderly and having drank his fill, he laid it down, and looked me in the face, carelessly scratching his backside; seeing he had done, I advanced and took away the shell, at which he never stirred.

"The forward disposition of the beast, towards a perfect familiarity, made me resolve to stay within the remainder of the day, no wise questioning but my company would, in a great measure, advance it; so I made a shift to sup upon a few roots I had about me, and went pretty early to bed; where I was no sooner laid, but the creature got across the feet thereof, and continued very quiet till the next morning that I got up, at which time he was also watching my actions: I made very much of him, which he took very composedly, standing to be stroked; then indeed I thought myself, in a manner, secure of him, and gave him his belly- full, as the day before, but having a pressing occasion to go out, I went to the door, thinking to shut him in till my return; but he followed me so close, that I could not open it, without endangering his getting out, which, though he appeared pretty tame, I did not care to venture, our acquaintance being so very new; yet as I was obliged to go, I did run the hazard; so opened the door by degrees, that if in case the beast should offer to run, I might take an opportunity to slip out and keep him in; but the creature never offering to go any further than I went, I did trust him to go with me, hoping, that if he went away, the kind usage he met with, would one day or other make him come back again; but to my great prize, as well as satisfaction, he readily returned with me, having waited my time; yet as I had occasion to go out a second time, wanting sticks to make fire, for which I was obliged to go near the place where most of his kind did resort, I was afraid to trust him with me, lest he should be decoyed by the others; therefore having taken up a bundle of cords wherewith I tie up my faggots, I watched an opportunity to get out, and leave him behind; but the beast was certainly apprehensive of my design; for it always kept near the door, looking wishfully at my bundle of cords, as desirous of such another, which having not for him, I cut a piece off mine, and gave it him and seeing I could not leave him behind, I ventured to let him go with me, which he did very orderly, never offering to go one step out of the way, though others of his kind came to look at him as he went by.

"Being come to the place where I used to cut dry sticks, having cut down a sufficient quantity, I began to lay some across my cord; the creature, having taken notice of it, did the same to his, and with that dexterity and agility, that his faggot was larger and sooner made than mine, which by that time being large enough, and as much as he could well carry, I bound it up, which set him to do the same with his, which was abundantly too large a load for him.

"Our faggots being made, I took up that which I had made, to see how he would go about taking up his, which being much too heavy for him, he could not lift; so running round it I believe twenty times, he looked me in the face, as craving help: having been sufficiently diverted with the out-of-the-way shifts he made, I gave him mine, and took up his; the poor animal appeared overjoyed at the exchange, therefore cheerfully takes up the bundle, and follows me home.

"Seeing myself, according to all probability, sure of the dear creature, whose late actions gave me such grounds to hope from him both service and pleasure, I returned my hearty thanks to kind Providence for his late prodigious gift; for certainly it was never heard of before, that in a desert place, such wild animals, who fly at the single appearance of a human creature, should voluntarily give itself to a man, and from the very beginning be so docile and tractable; oh! surely it was endued with more than natural instinct; for perfect reason was seen in all its actions: Indeed I was happy whilst I had him, but my happiness, alas! was not of long standing."

As he spoke I perceived tears in his eyes; "Pray, sir," said I, "what became of that wonderful creature?"

"Alas!" said he, "he was killed by monkeys of the other kind, who fell upon him one day as he was going for water by himself; for the poor dear creature was grown so knowing, that if at any time either firing or water was wanted, I had nothing to do, but to give him the bundle of cords or the empty vessel, and he would straight go and fetch either; in short, he wanted nothing but speech to complete him for human society."

"Indeed, sir," said I, "I cannot blame you for bemoaning the loss of so incomparable a creature, the account you give of him well deserves his memory a regret; but I hope this you have now, in a great measure, makes up your loss."

"O! not by far," replied the old man, "indeed he goes about with me, and will carry a faggot, or a vessel of water, pick a fowl, turn the spit or string when meat is roasting; yet he is nothing like my late dear Beaufidelle; for so I call that most lovely creature; besides this is unlucky, in imitating of me he often does me mischief: 'twas but the other day, that I had been writing for five or six hours, I had occasion to go out, and happened to leave my pen and ink upon my table, and the parchment I had been writing on close by it; I was no sooner gone but the mischievous beast falls to work, scrabbling over every word I had been writing; and when he had done he lays it by in the chest, as he saw me do what I had written, and takes out another, which e does the same to, and so to half a score more; my return prevented his doing more mischief; however in a quarter of an hour that I was absent, he blotted out as much s I had been full six months writing; indeed I as angry, and could have beaten him, but that I considered my revenge would not have repaired the damage, but rather perhaps add to my loss, by making the beast run away."

"Pray, sir," said I, "how came you by him, did he also give himself to you?"

"No," replied the old man, "I had him young, and by mere accident, unexpected and unsought for, having lost both time and labour about getting one in the room of him I had so unfortunately lost: the old ones are so fond of their young, that they never are from them, unless in their play they chase one another in the other kinds quarters, where their dams dare not follow them ; for they are such enemies to one another, that they watch all opportunity to catch whom they can of the contrary sort, whom they immediately strangle, which keeps their increase very backward, that would otherwise grow too numerous for the food the island produces; which is, I believe, the cause of their animosity.

'About eight years ago, which is the time I have had this beast, I was walking under one of the clusters of trees where the green sort of monkeys harbour, which, being the largest and most shady in the island I took the most delight therein; as I was walking, at a small distance from me this creature dropped off a tree, and lay for dead, which being of the grey kind, made me wonder less at the accident: I went and took him up, and accidentally handling his throat, I opened his wind-pipe, which was almost squeezed close by that which took him, whom my hidden coming prevented from strangling quite. I was extremely pleased at the event, by which I got what my past cares and diligence never could procure me. having pretty well recovered its breath, and seeing no visible hurt about it, I imagined I soon might recover him quite ; so hastened home with it, gave it warm milk, and laid it on my bed; so that with careful nursing, I quite recovered him; and with good keeping made the rogue thrive to that degree, that he has out-grown the rest of his kind."

"No question, sir," said I, "having taken such pains with him, you love him as well as his predecessor."

"I cannot say so neither," replied the old man, "though I cannot say but that I love the creature, but its having the ill fortune to be of that unlucky kind as was the death of my dear Beaufidelle, in a great measure lessens my affection; besides he falls so short both of his merit and beauty, that I must give the deceased the preference; and was it not for his cunning tricks, which often divert me, I should hardly value him at all; but he is so very cunning and facetious, that he makes me love him, notwithstanding I mortally hate his kind : I must divert you whilst dinner is getting ready, with an account of some of his tricks.

"Being extreme fond of me, he never scarce would be from me, but follow me everywhere; and as he used to go with me when I went to examine my nets, seeing me now and then take out game, he would of his own accord, when he saw me busy writing, go and fetch what happened to be taken.

One day finding a fowl in the net-bag, he pulled it alive as he brought it home; so that I could not see anything whereby to discern its kind: as soon as he came in he sets it down with such motions as did express joy ; the poor naked fowl was no sooner out of his clutches, but that it took too its heels for want of wings; its hidden escape so surprised the captor, that he stood amazed for a while, which gave the poor creature time to gain a considerable scope of ground; but the astonished beast, being recovered from his surprise, soon made after it, but was a considerable time before he could catch it, having nothing to lay hold of, so that the fowl would slip out of his hands: the race held about a quarter of an hour, in which time the poor creature, having run itself out of breath, was forced to lie down before its pursuer, who immediately threw himself upon it, so took it up in his arms, and brought it home; but was not so ready to set it down as before; for he held it by one leg till I had laid hold of it.

"I had a second time as good diversion, but after another manner; one morning early, whilst I was busy in my cottage, he went out unperceived by me, and having been a considerable time absent, I feared some such another accident had befallen him as had done his predecessor; so I went to see after him, and as he would often go and visit the nets in the wood, I went thither first, where I found him very busy with such an animal as this we have here, whom he found taken in one of the gap- nets, who, being near as big as he, kept him a great while struggling for mastership; sometimes he would take it by the ears, now and then by one leg, next by the tail, but could not get him along; at last he laid hold of one of his hind legs, and with the other hand smote him on the back, in order to drive him, not being able to pull him a-long; but the beast being too strong, still made towards the thick-set, where he certainly would have hauled the driver, had not I came up to help him." Thus the old gentleman entertained us with his monkey's tricks whilst dinner was dressing.

The dinner being ready, we went to the dwelling to eat it, leaving the young fellow that was with us to attend the roast meat whilst we eat the first dish.

The old gentleman having laid the cloth, which, though something coarse, being made out of part of a ship-sail, was very clean: he laid three shells on it, about the bigness of a middle- sized plate, but as beautiful as any nakes of pearl I ever saw. "Gentlemen," says he, "if you can eat off of shells, ye are welcome, I have no better plates to give you."

"sir," said I, "these are preferable to silver ones in my opinion, and I very much question whether any prince in Europe can produce so curious a service."

"They may richer," replied the old man, "but not cleaner."

The first dish he served was soup in a large deep shell, as fine as the first, and one spoon made of shell, which he said was all his stock, being not used nor expecting company; however he fetched a couple of muscle-shells, which he washed very clean, then gave Alvarado one, and took the other himself, obliging me to make use of the spoon; so we sat down, Alvarado and I upon the chest, which we drew near the table, and the old gentle-man (though much against his will) upon the chair.

Being sat down we fell to eating the soup, whose fragrant smell did excite my appetite, and I profess the taste thereof was so excellent, that I never eat any comparable to it at Pontack's, nor anywhere before; it was made of one half of the beast we took in the morning, with several sorts of herbs which eat like artichokes, asparagus and celery; there were also bits of roasted roots in it, instead of toasted bread, which added much to the richness of it, tasting like chestnuts; but what surprised me most, there were green peas in it, whose extraordinary sweetness was discernable from every other ingredient.

"Pity, said I, "the access to this island is so difficult, what a blessed spot of land would it make was it but inhabited! here naturally grows what in Europe we plough, till, and labour hard for."

"You say," replied the old man, "this would be a blessed spot of ground if it was inhabited; now I am quite of another opinion; for I think its blessing consists in its not being inhabited, being free of those curses your populous and celebrated cities regorge of; here's nothing but praises and thanksgivings heard; and as for Nature bestowing freely and of her own accord, what in Europe you are obliged to by industry and hard labour, in a manner to force from her, wonder not at; consider how much you daily rob her of her due, and charge her with slander and calumny; don't you frequently say, if a man is addicted to any vice, that it is his nature, when it is the effect and fruit of his corruption? So Nature, who attended the great origin of all things at the creation, is now, by vile wretches, deemed in fault for all their wickedness; had man remained in his first and natural state of innocence, Nature would also have continued her original indulgence over him; we may now think ourselves very happy, if that blessing attend our labour, which, before the fall of man, did flow on him, accompanied with ease and pleasure.

"Now these peas, which have so much raised your surprise, are indeed the growth of this island, though not its natural product, but the gifts of Providence, and the fruit of labour and industry. I have tilled the ground, Providence procured the seed, Nature gave it growth, and time increase; with seven peas and three beans I have, in four years' time, raised seed enough to stock a piece of ground, out of which I gather a sufficient quantity for my life, besides preserving fresh seed."

"No doubt, sir," said I, "but, when right means are taken, prosperity will attend."

By that time having eaten sufficiently of the soup, he would himself carry the remains to the young man in the kitchen, and fetch in the boiled meat and oyster-sauce, which he brought in another shell much of the same nature as that which the soup was served in, but something shallower, which did eat as choice as house-lamb.

Having done with that, he fetches in the other half of the beast roasted, and several sorts of delicate pickles I never eat of before, and mushrooms, but of curious colour, flavour and taste; those, said he, are the natural product of a particular spot of ground, where, at a certain time of the year, he did gather for the space of six days only, three sizes of mushrooms; for though they were all buttons and fit to pickle, by that time he had gathered all, he had also to stew, and some about four inches over, which he broiled, and eat as choice as any veal- cutlet.

"These pickles, sir," said I, "though far exceeding any I ever did eat in Europe, are really at this time needless, the meat wanting nothing to raise its relish, no flesh being more delicious."

Having done with that, I offered to take it away, but he no wise would permit me, so went away with it himself, and brought the fowls, at which I was something vexed; for I feared I should find no room in my stomach for any, having eat so heartily of the meat; but having, at his pressing request tasted of them, my appetite renewed at their inexpressible deliciousness, so I fell to eating afresh.

Having done with that dish, the young man, who having nothing to do in the kitchen, came, and was bid to take away and fall to; the mean time the good old man fetched us out of his dairy a small cheese of his own making, which being let down, he related to us the unaccountable manner he came by the antelopes that supplied him with the milk it was made withal, which introduced several weighty remarks on the wonderful acts of Providence, and the strictness of the obligations we lie under to our great benefactor; likewise the vast encouragement we have to love and serve God, the benefits and comforts of a clear conscience, as also the inestimable treasure of content; from that he epitomized upon the different tempers and dispositions of men, much commending timely education, as being a means to reverse and change evil inclinations, highly praising the charity of those pious people, who choose to bestow good schooling upon poor folk's children before clothing, and even food; the first being rather the most necessary, and the last the easiest to come at.

That discourse being ended, he inquired very carefully after the state of his dear native country, which, he said, he left fifty years ago, in a very indulgent disposition. I gave him the best account I could at that time of all the transactions that had happened in England since his absence.

"The relation of past evils," said he, "are but like pictures of earthquakes and shipwrecks, which affect the mind but slightly, and though I think myself out of any prince's power, yet I shall always partake with my countrymen's grief: Pray be implicit, what king have we now?"

"A complete patriot, and father to his subjects," said I, "both tender-hearted and merciful, encouraging virtue and suppressing vice, a promoter of religion, and an example of charity."

"Then," said he, in a manner as expressed zeal and joy, "long may that pious monarch live, and his blessed posterity for ever grace the British throne, and may Old England, by its faithful obedience and loyalty, henceforth atone for its past rebellions, that it may remove that execrable reproach it now lies under;" to which we all said "Amen."

Then he filled up the shell we drank out of, and drank good King George's health, which was succeeded with that of the royal family, and prosperity to the church: thus ended a most delicious and splendid dinner, and a conversation both delightful and instructive; but having not as then mentioned anything about his own history, which I most sadly longed to inquire into, I begged him to inform us by what accident he came there, and how he had so long maintained so good a state of health; to which he answered, time would not permit him to relate his own history, being very long, and the remainder of the day too short, but that he would, before we did part, give it me in writing; having, for want of other occupation, made a memorial: but as to the maintaining of his health, he would tell me by word of mouth.

"The receipt," said he, "is both short and easy, yet I fear you will not be able to follow it; look you, you must use none but wholesome exercises, observe a sober diet, and live a pious life; now if you can confine yourself to this way of living, I'll be bound that you will both preserve your health, and waste less money; but what's more valuable than all that, you will not endanger your precious soul."

I returned him thanks for his good advice, and promised him I would observe them as strictly as I could.

"I am afraid," replied he, "that will not be at all; you have too many powerful obstacles, the world and the flesh, from whom your affections must be entirely withdrawn, and all commerce prohibited, which is morally impossible, whilst living; therefore since you are obliged to converse with the world, I will give you a few cautions, which, if rightly taken, may be of use to you."

Make not the world your enemy, nor rely too much on its fidelity.And in all your dealings take this for a constant rule.

Be not too free with your friend; repetitions of favours often wear out friendship.

Waste not your vigour or substance on women, lest weakness and want be your reward:

Secrets are not safe in a woman's breast; 'tis a confinement the sex can't bear.Pass no contract over liquor; wine overcomes reason and dulls the understanding.

He who games puts his money in 'jeopardy, and is not sure of his own.

There's but little honour to wager on sure grounds, and less wisdom to lay upon a chance.

He who unlawful means advance to gain,I returned him thanks for his good morals, the copy whereof I begged he would give me in writing, for my better putting them in practice, to which he readily consented, wishing I might observe them, being very sure I should reap a considerable benefit thereby, both here and hereafter.

Instead of comfort, finds a constant pain;

What even by lawful arts we do possess,

Old age and sickness make it comfortless.

Be ruled by me, not to increase your store

By unjust means; for it will but make you poor:

Take but your due, and never covet more.

The day being pretty far spent, I was obliged to think of going, which much grieved me; for I was so taken with his company, that if I had not had a father and mother, whose years required my presence, I would have spent the rest of my days with him, I was so delighted with his company, and pleased with his way of living, that I almost overlooked my duty; but after a struggle with my inclination, I was obliged to yield to Nature. Thus having expressed my vexation to leave so good a man, I took my leave: the good old man perceiving my regret to leave him, could not conceal his to part with me.

"Indeed," said he with tears in his eyes, "I should have been very glad to have had a fellow-creature in this solitary island, especially one whom I think possessed with a good inclination, which I perceive you have, by your reluctance in leaving this innocent garden of life. I imagine you have relations in the world, that may stand in want of you; heavens protect you, and send you safe to them, I don't suppose you will ever see this island again, nor would advise you to venture, the approach of it is so dangerous; therefore, before you go, let me show you some of the rarities with which it abounds." I told him I was afraid time would not permit, but as he said about an hour or two would do, and that we had enough daylight, I went along with him.

Going out, and seeing the guns stand behind the door, I asked what he did with them: "I keep them," said he, "for a trophy of Providence's victory over my enemies, and a monument of my fourth miraculous deliverance." As we went along, he related to us the manner how he had been sacrilegiously robbed once by Indians, villainously invested twice by pirates, the ruffians having combined to carry him away like a slave to their own country, and there make a show of him as though he had been a monster.

Talking, we walked under several of the afore-mentioned clusters of trees, which proceed from one single plant; being come to one larger than the rest, and which he said he frequented most, being the largest in the island.

"This," said he, "covers with its own branches a whole acre of land;" so made several remarks on the wonderful works of Nature, which, said he, were all intended for the use and pleasure of man, everything in the universe containing such different virtues and properties, as were requisite to render life happy; from that he made several moral reflections on the fatal effects of disobedience, which is accounted a slight breach in duty, but is the mother of all sins.

That discourse held on a considerable time, till a parcel of each different kind of monkeys having met, fell to fighting, observing an admirable order during the fray, which withdrew our admiration from the preceding subject, and stopped us awhile to observe them.

The scuffle was very diverting whilst it lasted, which was but a short time; for they happened to perceive us, at which they parted, each sort running to their own quarters, which were not very distant from one another, so that from it they could see each others' motions.

"I am sorry," said I, "the battle was so soon over; they did cuff one another so prettily, that I could have stood an hour to see them."

"If you like the sport," said the old man, "I can soon set them at it again:" with that he takes out of his breeches' pocket some roasted roots, which he commonly carried about him to throw at them when he went that way, which made them less shy of him.

Having broke the roots in bits, he lays them down in their sight; for they on both fides were peeping from under the leaves of the trees where they harboured: then he cuts a score of sticks, about the bigness of one's finger, and near a foot and an half long, and lays them over the bits of roots; then we retired to some small distance, and hid ourselves behind the trees.

We were no sooner out of sight but that they hastened to the meat; the green monkeys, having less ground to go, were at them first, yet never stopped, but went on to hinder the others' approach, who vigorously strove to gain ground. The struggle was hard, and the victory often wavering; each party alternatively gave way, at last the grey sort kept the advantage, and drove their adversaries back, who being come where the sticks lay, immediately took them up, and charged their enemies with a fresh courage, like a yielding army that has received new forces: thus, with their clusters in the front, fell on their adversaries with such a vigour, knocking them down like our English mob at an election, so drove them back again almost to their own quarters.

In the mean time stragglers of both the kinds, who had not joined with the main bodies of the armies, seeing the coasts clear, and the provisions unguarded, unanimously fell to plunder, and quietly did eat what their comrades fought for; which the combatants perceiving, left off fighting, and of one accord turned upon the plunderers, who by that time having devoured the booty, left them the field without contending any farther.

The battle being over, the old gentleman would have us to go on, lest, said he, they should fall to it again out of revenge; for those creatures are very spiteful.

Having dispersed them by our advancing, as intended, we walked from under the trees, at the outside, to have a better view of the rock, which in some places, he said, did change its form as one approaches it; and, as he laid, being got clear of the trees, we saw at a distance, as it were, a considerable number of buildings, and here and there something like steeples, which represented a handsome city; and seemingly the houses appeared so plain, that had I not been prepossessed of the illusion, I should have taken it for such; but Alvarado and the young fellow could not be persuaded but what we saw were really buildings, and even in the island, though the old gentleman made us stop a while, the better to observe everything, then bid us keep our eyes fixed at what we looked at, and go on; we perceived every particular of what we observed to change its form; that which at first seemed to be fronting, showed itself either sideways or backwards; and so of every object, till being come at a certain distance, all the agreeableness of the perspective, of a sudden turned into its real shape, like a phantom, who, whilst the visible screens that which it sends before, by its vanishing leaves it discovered.

Being come as near the rock as the lake that parts it would permit, we could discern nothing in it that could in the least soften its ruggedness, or give it a more agreeable aspect than those that are represented in the pictures of shipwrecks.

The old gentleman thereupon made several learned observations on the alterations that distance works upon object and how easily our optics may be deceived, drawing from thence this inference, that we ought not to be too positive of the reality of what we see afar off, nor to affirm for truth that which we only heard of.

Having ended that discourse, he brought us to the other side of a jetting part of the rock, which advancing like a bastion of a fortified wall, screened from our eyes a second piece of wonder; a fine rainbow, issuing as it were out of the mouth of a giant, lying on the rock, reaching quite over the lake: at the bottom of it I could not but stop to admire the various colours it was of, which far exceeded in beauty and liveliness any I ever saw in the sky. I presently imagined it proceeded from the rays of the sun upon some pond or standing water, whose reflections did rise and meet the top, so caused that beautiful circle. But Alvarado, who, by what he had seen before, concluded the island was enchanted, said it was another illusion, of which the place was full, and would have gone away, but that the old man fell a laughing, and said, "'tis a sign you seldom enquire into natural causes; well, do but come a little nearer to it, and you will find that which you term an illusion is the natural effect of all fountains when the sun shines.

Being come to the place it proceeded from, it proved, as he said, only a fountain, but of the clearest and sweetest water that ever was tasted; but the place it did issue out of, was changed from the likeness of a giant, to that of some strange sort of creature, which, though having no particular resemblance, yet would bear being compared to several different things. The old man's opinion was that it resembled a whale, spurting water out at one nostril: Alvarado supposed it was more like a horse or a cow, and rather the last, there being horns plain to be seen; for my part I could find no proper similitude for it, but that of an old ruined monument, which formerly they did build over the heads of springs. Timothy Anchors, (for that was the name of the young fellow that was with us) being asked what he could make of it; "why really," said he, "nothing, unless it be an old patched up pump that stands at the end of my mother's court in Rosemary Lane," (which every spring runs out of itself) which comparison made us all to laugh.

Thus we differed in our opinions as to the likeness, yet agreed that was the finest fountain and the best water we ever saw or drank. What surprised me most, was the force wherewith it sprang from the rock that flood full five yards from the place it fell on, which was another subject of admiration, for certainly the arts of men could not have invented nor completed a more compact or pleasanter basin, though it had been for a fountain to adorn a monarch's garden: Indeed there was no masons nor any expert artists' exquisite works to be seen, but a great deal of nature's matchless understanding: there regularity, dimension, and proportion did conceit to make it useful, convenient and agreeable.

The basin was very near round, about eight foot diameter, a bank around it near a foot high, and as broad at top, slanting gently to the bottom, both inside and outside, which made a most pleasant and uniform bank, adorned with various small flowers and herbs of divers beautiful colours and most fragrant smells.

Having viewed with pleasure and amazement such regularity in a wild and uninhabited place, I walked about it as long as the time I could stay would permit; I proposed going, but the old gentleman, taking me by the hand, stopped me; "you have," said he, "bestowed a considerable time, observing the fertility of this island to now pray allow one minute for consideration; the object you have been admiring all this time is as wonderful and surprising as beautiful and pleasant; you see this fountain, which runs stiff and as large as your thumb, and therefore by computation may be allowed to give near hundred gallons of water in an hour; now it runs night and day, it neither decreases nor runs over its bank, but keeps to the same height."

"This, as you say, sir," said I, is really worth inquiring into;" so I went several times round it, searching for the place, whereby the overplus of the complement did expel, but could not discover it.

"Come," said he, "seek no more for that which Nature has so well concealed; I have spent many hours in that inquiry, and still remain ignorant, but have found the place out of which it runs into a fine fish-pond, about a mile inland; we will make it in our way to the lake; we may look at it as we go by, but can make no long stay, so we went on.

Going along we came by a hollow part of the rock, which went in like an alcove, with a great many concavities in it in rows one above another, as round niches where figures did stand: "now," said the old man, "we are here, I will entertain you with an invisible chorus of harmonious voices, little inferior to hautboys, trumpets, or other melodious music; here I twice come and pay my devotions each day."

Alvarado, who, by what he had already seen, was prepossessed that the island was full of enchantments, now was certain of it, and looked upon that place in the rock to be the receptacle of fiends and evil spirits; so would by no means stay; but takes his leave, saying he was not very curious of supernatural things.

"Supernatural," said the old man, "you can't well call it, though to you it may be very amazing; it is therefore well deserving your sight, I mean your hearing, the eyes having no share in the entertainment; we shall only sing a few psalms; I'm sure there can be no harm in that, but rather good, being a holy exercise in divine worship, in which all good souls ought to join."

"What may be," said Alvarado, "but I love to see those with whom I worship."

"I don't think myself as yet company for spirits."

"As for your part," said Alvarado, (speaking to me) "you may do what you please, but take care your curiosity don't cost you too clear: Tim and I will wait for you in the boat; but pray be not too long before you come," so having returned the old gentleman thanks for his kind entertainment, they went away, at which the good man was much affronted.

"What, said he, "do your friends imagine I deal with spirits! Besides where did he ever hear that devils loved to sing psalms? for here shall nothing else be sung: I would not for the world that those admirable echoes, that hitherto have repeated nothing but the Almighty's praises, would be polluted with the sound of any profane words." I endeavoured to excuse their timorousness, saying it was not a failing peculiar to themselves only, but to many besides; the old man allowed it, attributing the cause thereof to a very pernicious custom nurses have to frighten children, when they cry, with bugaboos and such things to make them quiet, which frightful ideas often make such deep impressions on their puerile minds, that when they come to mature age it is then hardly worn out, which intimidates man."

That discourse being ended, we advanced as near that part of the rock as the lake would permit; which in that place was not above seven or eight foot broad, so that we were within the concavity of the rock: "now," said the old man, let us lit down on this bank, and sing the hundred and seventeenth psalm."

"Indeed sir," said I, "I don't know it by heart, and I have no psalm-book about me."