Volume 1896a

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the

advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/ermine2.htm

John Ermine of the Yellowstone

Frederic Remington

Part 2: Chapters XI -XX

Continued from Part

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

John Ermine of the Yellowstone

Chapter XI

he soldiers who

had been in the wagon-train fight carried John Ermine's fame into cantonments,

and Major Searles never grew tired of the paean:

he soldiers who

had been in the wagon-train fight carried John Ermine's fame into cantonments,

and Major Searles never grew tired of the paean:

"I do not go to war for fifty dollars,

You can bet your boots that isn't not me lay.

When I fight, it's only glory which I collars,

Also to get me little beans and hay."

But his more ardent admirers frowned on this doggerel, and reminded the

songsters that no one of them would have made that courier's ride for a

thousand acres of Monongahela rye in bottles. As for Wolf-Voice, they appreciated

his attitude. "Business is business, and it takes money to buy marbles,"

said one to another.

But on the completion of the rude huts at the mouth of the Tongue, and

when the last wagon train had come through, there was an ominous preparation

for more serious things. It was in the air. Every white soldier went loping

about, doing everything from greasing a wagon to making his will.

"Ah, sacre, John," quoth Wolf-Voice, "am much disturb; dese Masta-Shella (13)

waas say dis big chief -- what you call de Miles? -- she medicin fighter;

she very bad mans; she keep de soldiers' toes sore all de taime. She no

give de dam de cole-moon, de yellow-grass moon; she hump de Sioux. Why

for we mak to trouble our head? We have dose box, dose bag, dose barrel

to heat, en de commissaire -- wael 'nough grub las' our lifetaime; but

de soldier say sure be a fight soon; dat Miles she begin for paw de groun'

it be sure sign. Wael, we mak' a skin dat las fight, hey, John?"

Ermine in his turn conceived a new respect for the white soldiers. If

their heels were heavy, so were their arms when it came to the final hug.

While it was not apparent to him just how they were going to whip the Sioux

and Cheyenne, it was very evident that the Indians could not whip the soldiers;

and this was demonstrated directly when Colonel Miles, with his hardy infantry,

charged over Sitting Bull's camp, and while outnumbered three to his one,

scattered and drove the proud tribesmen and looted their tepees. Not satisfied

with this, the grim soldier crawled over the snow all winter with his buffalo-coated

men, defying the blizzards, kicking the sleeping warriors out of their

blankets, killing and chasing them into the cold starvation of the hills.

So persistent and relentless were the soldiers that they fought through

the captured camps when the cold was so great that the men had to stop

in the midst of battle to light fires, to warm their fingers, which were

no longer able to work the breech-locks. Young soldiers cried in the ranks

as they perished in the frigid atmosphere; but notwithstanding, they never

stopped. The enemy could find no deep defile in the lonely mountains where

they were safe; and entrench where they would among the rocks, the steady

line charged over them, pouring bullets and shell. Ermine followed their

fortunes and came to understand the dying of "the ten thousand men." These

people went into battle with the intention of dying if not victorious.

They never consulted their heels, no matter what the extremity. By the

time of the green grass the warriors of the northern plains had either

sought their agencies or fled to Canada. Through it all Ermine had marched

and shot and frozen with the rest. He formed attachments for his comrades

that enthusiastic affection which men bring from the camp and battle-field,

signed by suffering and sealed with blood.

The snow had gone. The plains and boxlike bluff around the cantonments

had turned to a rich velvet of green. The troops rested after the tremendous

campaigns in the snow-laden, wind-swept hills, with the consciousness of

work well done. The Indians who had been brought in during the winter were

taking their first heart-breaking steps along the white man's road. The

army teams broke the prairie, and they were planting the seed. The disappearance

of the buffalo and the terrible white chief Bear-Coat, (14)

who followed and fought them in the fiercest weather, had broken their

spirits. The prophecies of the old beaver-men, which had always lain heavily

on the Indian mind, had come true at last the whites had come; they had

tried to stop them and had failed.

The soldiers' nerves tingled as they gathered round the landing. They

cheered and laughed and joked, slapped and patted hysterically, and forgot

the bilious officialism entirely.

Far down the river could be seen the black funnel of smoke from the

steamboat their only connection with the world of the white men. It bore

letters from home, luxuries for the mess-chest, and best of all, news of

the wives and children who had been left behind when they went to war.

Every one was in a tremor of expectancy except the Indians, who stood

solemnly apart in their buffalo-robes, and John Ermine. The steamboat did

not come from their part of the world, and brought nothing to them; still

Ermine reflected the joyousness of those around him, and both he and the

Indians knew a feast for their eyes awaited them.

In due course the floating house -- for she looked more like one than

a boat -- pushed her way to the landing, safe from her thousand miles of

snags and sandbars. A cannon thudded and boomed. The soldiers cheered,

and the people on the boat waved handkerchiefs when they did not use them

to wipe happy tears away; officers who saw their beloved ones walked to

and fro in caged impatience. When the gang-planks were run out, they swarmed

aboard like Malay pirates. Such hugging and kissing as followed would have

been scandalous on an ordinary occasion; lily-white faces were quite buried

in sunburnt mustaches on mahogany-brown skins. The unmarried men all registered

a vow to let no possible occasion to get married escape them, and little

boys and girls were held aloft in brawny arms paternal. A riot of good

spirits reigned.

"For Heaven's sake, Mary, did you bring me my summer underwear?"

"Oh, don't say you forgot a box of cigars, Mattie."

"If you have any papers or novels, they will save me from becoming an

idiot," and a shower of childish requests from their big boys greeted the

women.

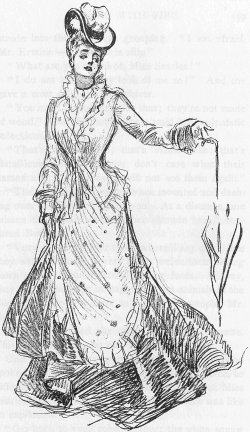

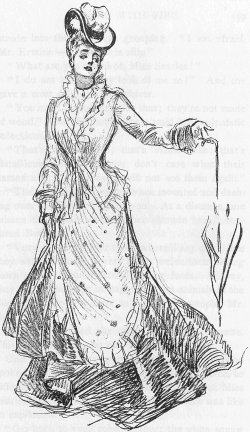

In truth, it must be stated that at this period the fashion insisted

upon a disfigurement of ladies which must leave a whole generation of noble

dames forgotten by artists of all time. They loosened and tightened their

forms at most inappropriate places; yet underneath this fierce distortion

of that bane of woman, Dame Fashion, the men were yet able to remember

there dwelt bodies as beautiful as any Greek ever saw or any attenuated

Empire dandy fancied.

"Three cheers for the first white women on the northern buffalo range!"

"See that tent over there?" asked an officer of his 'Missis,' as he

pointed toward camp; "well, that's our happy home; how does it strike you?"

A bunch of "shave-tails" were marched ashore amid a storm of good-natured

raillery from the "vets " and mighty glad to feel once again the grit under

their brogans. Roustabouts hustled bags and boxes into the six-mule wagons.

The engine blew off its exhaust in a frail attempt to drown the awful profanity

of the second mate, while humanity boiled and bubbled round the great river-box.

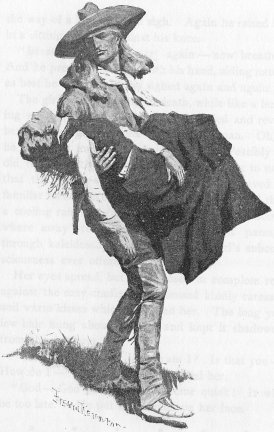

The Indians stood motionless, but their keen eyes missed no details

of the strange medley. Ermine leaned on a wagon-tail, carefully paring

a thin stick with a jack-knife. He was arrayed for a gala day in new soldier

trousers, a yellow buckskin shirt beautifully beaded by the Indian method,

a spotted white handkerchief around his neck, buckskin leggings on the

lower leg above gay moccasins, a huge skinning-knife and revolver in his

belt, and a silver watch chain. His golden hair was freshly combed, and

his big rakish sombrero had an eagle feather fastened to the crown, dropping

idly to one side, where the soft wind eddied it about.

The John Ermine of the mountain den was a June-bug beside this butterfly,

but no assortment of color can compete with a scarlet blanket when the

clear western sun strikes on it; so in consequence Ermine was subdued by

Wolf-Voice, who stood be side him thus arrayed.

As the people gathered their bags and parcels, they came ashore in small

groups, the women and children giving the wild Indians the heed which their

picturesque appearance called for, much of this being in the form of little

shivers up and down the spine. A true old wolf-headed buffalo Indian would

make a Japanese dragon look like a plate of ice-cream, and the Old Boy

himself would have to wave his tail, prick up his sharp ears, and display

the best of his Satanic learning to stand the comparison.

Major Searles passed on with the rest, beaming like a June morning,

his arms full of woman's equipment -- Mrs. Searles on one side and his

daughter on the other.

"Hello, Ermine."

"How do, Major?" spoke the scout as he cast his whittling from him.

"This is John Ermine, who saved my life last winter, my dear. This is

Mrs. Searles, John."

She bowed, but the scout shook hands with her. Miss Searles, upon presentation,

gave Ermine a most chilling bow, if raising the chin and dropping the upper

eyelids can be so described; and the man who pushed his pony fearlessly

among the whirling savages recoiled before her batteries and stood irresolute.

Wolf-Voice, who had not been indicated by the Major, now approached,

his weird features lighted up with what was intended as pleasantry, but

which instead was rather alarming.

"How! how me heap glad to see you." And to Miss Searles, "How! how you

heap look good." After which they passed on.

"My, my, papa, did you ever see such beautiful hair as that man Ermine

has?" said Katherine Searles. "It was a perfect dream."

"Yes, good crop that -- 'nough to stuff a mattress with; looks better

to-day than when it's full of alkali dust," replied the Major.

"If the young man lost his hat, it would not be a calamity," observed

the wife.

" And, papa, who was that dreadful Indian in the red blanket?"

Katherine

"Oh, an old scoundrel named Wolf-Voice, but useful in his place. You

must never feed him, Sarah, or he will descend on us like the plague of

locusts. If he ever gets his teeth into one of our biscuits, I'll have

to call out the squad to separate him from our mess-chest."

A strange thought flashed through John Ermine's head -- something more

like the stroke of an axe than a thought, and it had deprived him of the

power of speech. Standing motionless and inert, he watched the girl until

she was out of sight. Then he walked away from the turmoil, up along the

river-bank.

Having gained a sufficient distance, he undid the front of his shirt

and took out a buckskin bag, which hung depended from his neck. It contained

his dried horse's hoof and the photograph of a girl, the one he had picked

up in the moonlight on the trail used by the soldiers from Fort Ellis.

He gazed at it for a time, and said softly, "They are the same, that

girl and this shadow." And he stood scrutinizing it, the eyes looking straight

into his as they had done so often before, until he was intimate with the

image by a thousand vain imaginings. He put it back in his bag, buttoned

his shirt, and stood in a brown study, with his hands behind his back,

idly stirring the dust with the point of one moccasin.

"It must have been -- it must have been Sak-a-war-te who guided me in

the moonlight to that little shadow paper there in the road to that little

spot in all this big country; in the night-time and just where we cut that

long road; it means something it -- must be." And he could get no farther

with his thoughts as he walked to his quarters.

Along the front of the officers' row he saw the bustle, and handshaking,

laughter, and quick conversation. Captain Lewis came by with a tall young

man in citizen's clothes, about whom there was a blacked, brushed, shaved

appearance quite new on the Tongue.

"I say, and who is that stunning chap?" said this one to Lewis, in Ermine's

hearing.

"One of my men. Oh, come here, Ermine. This is Mr. Sterling Harding,

an Englishman come out to see this country and hunt. You may be able to

tell him some things he wants to know."

The Englishman

The two young men shook hands and stood irresolutely regarding each other.

Which had the stranger thoughts concerning the other or the more curiosity

cannot be stated, but they both felt the desire for better acquaintance.

Two strangers on meeting always feel this --or indifference, and sometimes

repulsion. The relations are established in a glance.

"Oh, I suppose, Mr. Ermine, you have shot in this country."

" Yes, sir," -- Ermine had extended the "sir" beyond shoulder-straps

to include clean shirts, -- "I have shot most every kind of thing we have

in this country except a woman,"

"Oh! ha! ha ha!" And Harding produced a cigar-case.

"A woman? I suppose there hasn't been any to shoot until this boat came.

Do you intend to try your hand on one? Will you have a cigar?"

"No, sir ; I only meant to say I had shot things. I suppose you mean

have I hunted."

"Yes, yes exactly; hunted is what I mean."

"Well then, Mr. Sterling Harding, I have never done anything else."

"Mr. Harding, I will leave you with Ermine; I have some details to look

after. You will come to our mess for luncheon at noon?" interjected Captain

Lewis.

"Yes, with pleasure, Captain." Whereat the chief of scouts took himself

off.

"I suppose, Mr. Ermine, that the war is quite over, and that one may

feel free to go about here without being potted by the aborigines," said

Harding.

"The what? Never heard of them. I can go where I like without being

killed, but I have to keep my eyes skinned."

"Would you be willing to take me out? I should expect to incur the incidental

risks of the enterprise," asked the Englishman, who had taken the incidental

risks of tigers in India and sought "big heads" in many countries irrespective

of dangers.

"Why, yes; I guess Wolf-Voice and I could take you hunting easily enough

if the Captain will let us go. We never know here what Bear-Coat is going

to do next; it may be 'boots and saddles' any minute," replied the scout.

"Oh, I imagine, since Madam has appeared, he may remain quiet and I

really understand the Indians have quite fled the country," responded Harding.

"Mabeso; you don't know about Indians, Mr. Harding. Indians are uncertain;

they may come back again when their ponies fill up on the green grass."

"Where would you propose to go, may I ask?"

Ermine thought for a time, and asked, "Would you mind staying out all

one moon, Mr. Harding?"

"One moon? You mean thirty days. Yes, three moons, if necessary. My

time is not precious. Where would you go?"

"Back in the mountains -- back on the Stinking Water; a long way from

here, but a good place for the animals. It is where I come from, and I

haven't been home in nearly a year. I should like to see my people," continued

Ermine.

"Anywhere will do; we will go to the Stinking Water, which I hope belies

its name. You have relatives living there, I take it."

"Not relatives; I have no relations anywhere on the earth, but I have

friends," he replied.

"When shall we start?"

Ermine waved his hand a few times at the sky and said "So many," but

it failed to record on the Englishman's mind. He was using the sign language.

The scout noted this, and added, "Ten suns from now I will go if I can."

"Very well; we will purchase ponies and other necessaries meanwhile,

and will you aid me in the preparations, Mr. Ermine? How many ponies shall

we require?"

"Two apiece one to ride and the other to pack," came the answer to the

question.

A great light dawned upon Harding's mind. To live a month with what

one Indian pony could carry for bedding, clothes, cartridges, and food.

His new friend failed, in his mind, to understand the requirements of an

English gentleman on such quests.

"But, Mr. Ermine, how should I transport my heads back to this point

with only one pack-animal?"

"Heads? heads? back here? "stumbled the light-horseman. "What heads?"

"Why, the heads of such game as I might be so fortunate as to kill."

"What do you want of their heads? We never take the heads. We give them

to our little friends, the coyotes," queried Ermine.

"Yes, yes, but I must have the heads to take back to England with me.

I am afraid, Mr. Ermine, we shall have to be more liberal with our pack-train.

However, we will go into the matter at greater length later."

Sterling Harding wanted to refer to the Captain for further understanding

of his new guide. He felt that Lewis could make the matter plain to Ermine

by more direct methods than he knew how to employ. As the result of world-wide

wanderings, he knew that the Captain would have to explain to Ermine that

he was a crazy Englishman who was all right, but who must be humored. To

Harding this idea was not new; he had played his blood-letting ardor against

all the forms of outlandish ignorance. The savages of many lands had eaten

the bodies of which the erratic Englishman wanted only the heads.

So to Lewis went Harding. "I say, Captain, your Ermine there is an artless

fellow. He is proposing to Indianize me, to take me out for a whole moon,

as he calls it, with only one pack-pony to carry my be longings. Also he

fails, I think, to comprehend that I want to bring back the heads of my

game."

"Ha! I will make that plain to him. You see, Mr. Harding, you are the

first Englishman he ever encountered; fact is he is range bred, unbranded

and wild. I have ridden him, but I use considerable discretion when I do

it, or he would go up in the air on me," explained Lewis. "He is simple,

but he is honest, faithful, and one of the very few white men who know

this Indian country. Long ago there were a great many hunters and trappers

in these parts; men who worked for the fur companies, but they have all

been driven out of the country of late years by the Indians, and you will

be lucky to get Ermine. There are plenty of the half-breeds left, but you

cannot trust them. They might steal from you, they might abandon you, or

they might kill you. Ermine will probably take you into the Crow country,

for he is solid with those people. Why, half the time when I order Crow

scouts to do something they must first go and make a talk with Ermine.

He has some sort of a pull with them God knows what. You may find it convenient

to agree with him at times when you naturally would not; these fellows

are independent and follow their fancies pretty much. They don't talk,

and when they get an idea that they want to do anything, they proceed immediately

to do it. Ermine has been with me nearly a year now, but I never know what

minute I am to hear he has pulled out."

Seeing Ermine some little distance away, the Captain sent an orderly

after him. He came and leant with one hand on the tent-pole of the fly.

"Ermine, I think you had better take one or two white packers and at

least eight or ten animals with you when you go with Mr. Harding."

" All right, sir, we can take as many packers as he likes, but no wagons."

Having relieved the scout of his apprehensions concerning wagons, the

bond was sealed with a cigar, and he departed, thinking of old Crooked-Bear's

prediction that the white men would take him to their hearts. Underneath

the happy stir of his faculties on this stimulating day there played a

new emotion, indefinite, undefinable, a drifting, fluttering butterfly

of a thought which never alighted anywhere. All day long it flitted, hovered,

and made errant flights across his golden fancies -- a glittering, variegated

little puff of color.

On the following morning Harding hunted up John Ermine, and the two walked

about together, the Englishman trying to fire the scout with his own passion

for strange lands and new heads.

To the wild plainsman the land was not new; hunting had its old everyday

look, and the stuffed heads of game had no significance. His attention

was constantly interrupted by the little flutter of color made more distinct

by a vesper before the photograph.

" Let us go and find your friend, Wolf-Voice," said Harding, which they

did, and the newcomer was introduced. The Englishman threw kindly, wondering

eyes over the fiercely suspicious face of the half-breed, whose evil orbs

spitted back at him.

"Ah, yees you was go hunt. All-right; I weel mak' you run de buffalo,

shoot dose elk, trap de castor, an you shall shake de han' wid de grizzly

bear. How much money I geet hey?"

quot;Ah, you will get the customary wages, my friend, and if you give

me an opportunity to shake hands with a grizzly, your reward will be forthcoming,"

replied the sportsman.

"Very weel; keep yur heye skin on me, when you see me run lak hell weel,

place where I was run way from, dare ees mousier's grizzly bear, den you

was go up shake han', hey?"

Harding laughed and offered the man a cigar, which he handled with four

fingers much as he might a tomahawk, having none of the delicate art native

to the man of cigars or cigarettes. A match was proffered, and Wolf-Voice

tried diligently to light the wrong end. The Englishman violently pulled

Ermine away, while he nearly strangled with suppressed laughter. It was

distinctly clear that Wolf-Voice must go with them.

"Your friend Wolf-Voice seems to be quite an individual person."

"Yes, the soldiers are always joshing him, but he doesn't mind. Sometimes

they go too far. I have seen him draw that skinning-knife, and away they

go like a flock of birds. Except when he gets loaded with soldier whiskey,

he is all right. He is a good man away from camp," said Ermine.

" He does not appear to be a thoroughbred Indian," observed Harding.

"No, he's mixed; he's like that soup the company cooks make. He is not

the best man in the world, but he is a better man in more places than I

ever saw," said Ermine, in vindication.

"Shall we go down to the Indian camp and try to buy some ponies, Ermine?"

"No, I don't go near the Sioux; I am a kind of Crow. I have fought with

them. They forgive the soldiers, but their hearts are bad when they look

at me. I'll get Ramon to go with you when you buy the horses. Ramon was

a small trader before the war, used to going about with a half-dozen pack-horses,

but the Sioux ran him off the range. He has pack saddles and rawhide bags,

which you can hire if you want to," was explained.

"All right; take me to Ramon if you will."

"I smoke," said Ermine as he led the way.

Having seen that worthy depart on his trading mission with Harding in

tow, Ermine felt relieved. Impulse drew him to the officers' row, where

he strolled about with his hands in his cartridge-belt. Many passing by

nodded to him or spoke pleasantly. Some of the newly arrived ladies even

attempted conversation; but if the soldiers of a year ago were difficult

for Ermine, the ladies were impossible. He liked them; their gentle faces,

their graceful carriage, their evident interest in him, and their frank

address called out all his appreciation. They were a revelation after the

squaws, who had never suggested any of these possibilities. But they refused

to come mentally near him, and he did not know the trail which led to them.

He answered their questions, agreed with whatever they said, and battled

with his diffidence until he made out to borrow a small boy from one mother,

proposing to take him down to the scout camp and quartermaster's corral

to view the Indians and mules.

He had thought out the proposition that the Indians were just as strange

to the white people as the white people were to them, consequently he saw

a social opening. He would mix these people up so that they could stare

at each other in mutual perplexity and bore one another with irrelevant

remarks and questions.

"Did Mr. Butcher-Knife, miss Madam Butcher-Knife? " asked a somewhat

elderly lady on one occasion, whereat the Indian squeezed out an abdominal

grunt and sedately observed to "Hairy-Arm," in her own language, that "the

fat lady could sit down comfortably," or words that would carry this thought.

The scout who was acting as their leader upon this occasion emitted

one loud "A-ha!" before he could check himself. The lady asked what had

been said. Ermine did not violate a rule clearly laid down by Crooked-Bear,

to the effect that lying was the sure sign of a man's worthlessness. He

answered that they were merely speaking of something which he had not seen,

thus satisfying his protégé.

After a round or two of these visits this novelty was noised about the

quarters, and Ermine found himself suddenly accosted. By his side was the

original of his cherished photograph, accompanied by Lieutenant Butler

of the cavalry, a tall young man whose body and movements had been made

to conform to the West Point standards.

" Miss Searles has been presented, I believe. She is desirous of visiting

the scout camp. Would you kindly take us down?"

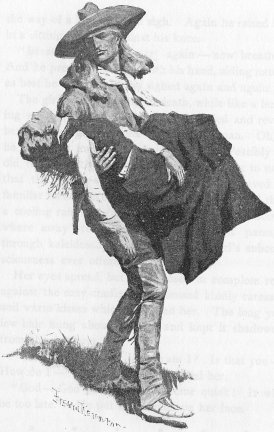

John Ermine's soul drifted out through the top of his head in unseen

vapors, but he managed to say that he would. He fell in beside the young

woman, and they walked on together. To be so near the reality, the literal

flesh and blood of what had been a long series of efflorescent dreams,

quite stirred him. He gathered slowly, after each quick glance into the

eyes which were not like those in the photograph; there they were set and

did not resent his fancies; here they sparkled and talked and looked unutterable

things at the helpless errant.

Miss Searles had been to a finishing school in the East, and either

the school was a very good one or the little miss exceedingly apt, but

both more probably true. She had the delicate pearls and peach-bloom on

her cheeks to which the Western sun and winds are such persistent enemies,

and a dear little nose tipped heavenward, as careless as a cat hunting

its grandmother.

The rustle of her clothes mingled with little songs which the wind sang

to the grass, a faint freshness of body with delicate spring-flower odors

drifted to Ermine's active nostrils. But the eyes, the eyes, why did they

not brood with him as in the picture? Why did they arch and laugh and tantalize?

His earthly senses had fled; gone somewhere else and left a riot in

his blood. He tripped and stumbled, fell down, and crawled over answers

to her questions, and he wished Lieutenant Butler was farther away than

a pony could run in a week.

She stopped to raise her dress above the dusty road, and the scout overrode

the alignment.

"Mr. Ermine, will you please carry my parasol for me?"

"Will you please carry my parasol for me?"

The object in question was newer to him than a man-of-war would have

been. The prophet had explained about the great ships, but he had forgotten

parasols. He did not exactly make out whether the thing was to keep the

sun off, or to hide her face from his when she wanted to. He retraced his

steps, wrapped his knuckles around the handle with a drowning clutch, and

it burned his hand. If previously it had taken all his force to manoeuvre

himself, he felt now that he would bog down under this new weight. Atlas

holding the world had a flying start of Ermine.

He raised it above her head, and she looked up at him so pleasantly,

that he felt she realized his predicament ; so he said, "Miss Searles,

if I lug this baby tent into that scout camp, they will either shoot at

us, or crawl the ponies and scatter out for miles. I think they would stand

if you or the Lieutenant pack it; but if I do this, there won't be anything

to see but ponies' tails wavering over the prairie."

"Oh, thank you; I will come to your rescue, Mr. Ermine." And she did.

"It is rather ridiculous, a parasol, but I do not intend to let the

sun have its way with me." And glancing up, "Think if you had always carried

a parasol, what a complexion you would have."

"But men don't carry them, do they?"

"Only when it rains; they do then, back in the States," she explained.

Ermine replied, "They do -- hum!" and forthwith refused to consider

men who did it.

"I think, Mr. Ermine, if I were an Indian, I should very much like to

scalp you. I cannot cease to admire your hair."

"Oh, you don't have to be an Indian, to do that. Here is my knife; you

can go ahead any time you wish," came the cheerful response.

"Mr. Butler, our friend succumbs easily to any fate at my hands, it

seems. I wonder if he would let me eat him," said the girl.

" I will build the fire and put the kettle on for you." And Ermine was

not joking in the least, though no one knew this.

They were getting into the dangerous open fields, and Miss Searles urged

the scout in a different direction.

"Have you ever been East?"

"Yes," he replied, "I have been to Fort Buford."

The parasol came between them, and presently, "Would you like to go

east of Buford -- I mean away east of Buford," she explained.

"No; I don't want to go east or west, north or south of here," came

the astonishing answer all in good faith, and Miss Searles mentally took

to her heels. She feared seriousness.

"Oh, here are the Indians," she gasped, as they strode into the grotesque

grouping. " I am afraid, Mr. Ermine -- I know it is silly."

"What are you afraid of, Miss Searles?"

"I do not know; they look at me so!" And she gave a most delicious little

shiver.

"You can't blame them for that; they're not made of wood." But this

lost its force amid her peripatetic reflections.

"That's Broken-Shoe; that's White-Robe; that's Batailleur -- oh, well,

you don't care what their names are; you probably will not see them again."

"They are more imposing when mounted and dashing over the plains, I

assure you. At a distance, one misses the details which rather obtrude

here," ventured Butler.

"Very well; I prefer them where I am quite sure they will not dash.

I very much prefer them sitting down quietly -- such fearful-looking faces.

Oh my, they should be kept in cages like the animals in the Zoo. And do

you have to fight such people, Mr. Butler?"

"We do," replied the officer, lighting a cigarette. This point of view

was new and amusing.

One of the Indians approached the party. Ermine spoke to him in a loud,

guttural, carrying voice, so different from his quiet use of English, that

Miss Searles fairly jumped. The change of voice was like an explosion.

"Go back to your robe, brother; the white squaw is afraid of you --

go back, I say!"

The intruder hesitated, stopped, and fastened Ermine with the vacant

stare which in such times precede sudden, uncontrollable fury among Indians.

Again Ermine spoke: "Go back, you brown son of mules; this squaw is

my friend; I tell you she is afraid of you. I am not. Go back, and before

the sun is so high I will come to you. Make this boy go back, Broken-Shoe;

he is a fool."

The old chieftain emitted a few hollow grunts, with a click between,

and the young Indian turned away.

"My! Mr. Ermine, what are you saying? Have I offended the Indian? He

looks daggers; let us retire -- oh my, let us go -- quick -- quick!" And

Ermine, by the flutter of wings, knew that his bird had flown. He followed,

and in the safety of distance she lightly put her hand on his arm.

"What was it all about, Mr. Ermine? Do tell me."

Ermine's brain was not working on schedule time, but he fully realized

what the affront to the Indian meant in the near future. He knew he would

have to make his words good; but when the creature of his dreams was involved,

he would have measured arms with a grizzly bear.

"He would not go back," said the scout, simply.

"But for what was he coming?" she asked.

"For you," was the reply.

"Goodness gracious! I had done nothing; did he want to kill me?"

"No, he wanted to shake hands with you; he is a fool."

"Oh, only to shake hands with me? And why did you not let him? I could

have borne that."

"Because he is a fool," the scout ventured, and then in tones which

carried the meaning, "Shake hands with you!"

"I see; I understand; you were protecting me; but he must hate you.

I believe he will harm you; those dreadful Indians are so relentless, I

have heard. Why did we ever go near the creatures? What will he do, Mr.

Ermine?"

The scout cast his eye carefully up at the sky and satisfied the curiosity

of both by drawling, "A -- hu!"

"Well well, Mr. Ermine, do not ever go near them again; I certainly

would not if I were you. I shall see papa and have you removed from those

ghastly beings. It is too dreadful. I have seen all I care to of them;

let us go home, Mr. Butler."

The two the young lady and the young man bowed to Ermine, who touched

the brim of his sombrero, after the fashion of the soldiers. They departed

up the road, leaving Ermine to go, he knew not where, because he wanted

to go only up the road. The abruptness of white civilities hashed the scout's

contempt for time into fine bits; but he was left with something definite,

at least, and that was a deep, venomous hatred for Lieutenant Butler; that

was something he could hang his hat on. Then he thought of the "fool,"

and his footsteps boded ill for that one.

"That Ermine is such a tremendous man; do you not think so, Mr. Butler?"

"He seems a rather forceful person in his simple way," coincided the

officer. "You apparently appeal to him strongly. He is downright romantic

in his address, but I cannot find fault with the poor man. I am equally

unfortunate."

"Oh, don't, Mr. Butler; I cannot stand it; you are, at least, sophisticated."

"Yes, I am sorry to say I am."

"Oh, please, Mr. Butler," with a deprecating wave of her parasol, "but

tell me, aren't you afraid of them?"

"I suppose you mean the Indians. Well, they certainly earned my respect

during the last campaign. They are the finest light-horse in the world,

and if they were not encumbered with the women, herds, and villages; if

they had plenty of ammunition and the buffalo would stay, I think there

would be a great many army widows, Miss Searles."

" It is dreadful; I can scarcely remember my father; he has been made

to live in this beast of a country since I was a child." Such was the lofty

view the young woman took of her mundane progress.

"Shades of the vine-clad hills and citron groves of the Hudson River!

I fear we brass buttoners are cut off. I should have been a lawyer or a

priest no, not a priest; for when I look at a pretty girl I cannot feel

any priesthood in my veins."

Miss Searles whistled the bars of "Halt" from under the fortification

of the parasol.

"Oh, well, what did the Lord make pretty women for?"

"I do not know, unless to demonstrate the foolishness of the line of

Uncle Sam's cavalry," speculated the arch one. "Mr. Butler, if you do not

stop, I shall run."

"All right; I am under arrest, so do not run; we are nearly home. I

reserve my right to resume hostilities, however. I insist on fair play

with your sage-brush admirer. Since we met in St. Louis, I have often wondered

if we should ever see each other again. I always ardently wished we could."

"Mr. Butler, you are a poor imitation of our friend Ermine; he, at least,

makes one feel that he means what he says," she rejoined.

"And you were good enough to remind me that I was sophisticated."

"I may have been mistaken," she observed. She played the batteries of

her eyes on the unfortunate soldier, and all of his formations went down

before them. He was in love, and she knew it, and he knew she knew it.

He felt like a fool, but tried not to act one, with the usual success

of lovers. He was an easy victim of one of those greatest of natural weaknesses

men have. She had him staked out and could bring him into her camp at any

time the spirit moved her. Being a young person just from school, she found

affairs easier than she had been led to suspect. In the usual girl way

she had studied her casts, lures, and baits, but in reality they all seemed

unnecessary, and she began to think some lethal weapon which would keep

her admirers at a proper distance more to the purpose.

The handsome trooper was in no great danger, she felt, only she must

have time; she did not want every thing to happen in a minute, and the

greatest dream of life vanish forever. Besides, she intended never, under

any circumstances, to haul down her flag and surrender until after a good,

hard siege.

They entered the cabin of the Searles, and there told the story of the

morning's adventures. Mrs. Searles had the Indians classified with rattlesnakes,

green devils, and hyenas, and expected scenes of this character to happen.

The Major wanted more details concerning Ermine. " Just what did he

say, Butler?"

"I do not know; he spoke in some Indian language."

"Was he angry, and was the Indian who approached you mad?"

"They were like two dogs who stand ready to fight, teeth bared, muscles

rigid, eyes set and just waiting for their nerves to snap," explained Butler.

"Oh, some d---- Indian row, no one knows what, and Ermine won't tell;

yet as a rule these people are peaceful among themselves. I will ask him

about it," observed the Major.

"Why can't you have Mr. Ermine removed from that awful scout camp, papa?

Why can't he be brought up to some place near here? I do not see why such

a beautiful white person as he is should have to associate with those savages,"

pleaded the graceful Katherine.

"Don't worry about Ermine, daughter; you wouldn't have him rank the

Colonel out of quarters, would you? I will look into this matter a little."

Meanwhile the young scout walked rapidly toward his camp. He wanted

to do something with his hands, something which would let the gathering

electricity out at his finger-ends and relieve the strain, for the trend

of events had irritated him.

Going straight to his tent, he picked up his rifle, loaded it, and buckled

on the belt containing ammunition for it. He twisted his six-shooter round

in front of him, and worked his knife up and down in its sheath. Then he

strode out, going slowly down to the scout fire.

The day was warm; the white-hot sun cut traceries of the cottonwood

trees on the ground. A little curl of blue smoke rose straight upward from

the fire, and in a wide ring of little groups sat or lounged the scouts.

They seemingly paid no attention to the approach of Ermine, but one could

not determine this; the fierce Western sun closes the eyelids in a perpetual

squint, and leaves the beady eyes a chance to rove unobserved at a short

distance.

Ermine came over and walked into the circle, stopping in front of the

fire, thus facing the young Indian to whom he had used the harsh words.

There was no sound except the rumble of a far-off government mule team

and the lazy buzz of flies. He deliberately rolled a cigarette. Having

done this to his satisfaction, he stooped down holding it against the coals,

and it was ages before it caught fire. Then he put it to his lips, blew

a cloud of smoke in the direction of his foe, and spoke in Absaroke.

" Well, I am here."

The silence continued; the Indian looked at him with a dull steady stare,

but did nothing; finally Ermine withdrew. He understood; the Indian did

not consider the time or opportunity propitious, but the scout did not

flatter himself that such a time or place would never come. That was the

one characteristic of an Indian of which a man could be certain.

John Ermine lay on his back in his tent, with one leg crossed over the

other. His eyes were idly attracted by the play of shadows on the ducking,

but his mind was visiting other places. He was profoundly discontented.

During his life he had been at all times an easy-going person -- taught

in a rude school to endure embarrassing calamities and long-continued personal

inconveniences by flood and hunger, bullets and snow. He had no conception

of the civilized trait of acquisitiveness whereby he had escaped that tantalization.

He desired military distinction, but he had gotten that. No man strode

the camp whose deeds were better recognized than his, not even the Colonel

commanding.

His attitude toward mankind had always been patient and kindly except

when urged into other channels by war. He even had schooled himself to

the irksome labor at the prophet's mine, low delving which seemed useless;

and had acquiesced while Crooked-Bear stuffed his head with the thousand

details of white mentality; but now vaguely he began to feel a lack of

something, an effort which he had not made a something he had left undone;

a difference and a distinction between himself and the officers who were

so free to associate with the creature who had borrowed his mind and given

nothing in return. No one in the rude campaigning which had been the lot

of all since he joined had made any noticeable social distinction toward

him -- rather otherwise; they had sought and trusted him, and more than

that, he had been singled out for special good will. He was free to call

at any officer's quarters on the line, sure of a favorable reception; then

why did he not go to Major Searles's? At the thought he lay heavier on

the blanket, and dared not trust his legs to carry out his inclinations.

The camp was full of fine young officers who would trust their legs

and risk their hearts he felt sure of that. True, he was subject to the

orders of certain officials, but so were they. Young officers had asked

him to do favors on many occasions, and he did them, because it was clear

that they ought to be done, and he also had explained devious plains-craft

to them of which they had instantly availed themselves. The arrangement

was natural and not oppressive.

Captain Lewis could command him to ford a rushing torrent: could tell

him to stand on his head and be d---- quick about it, and of course he

would do anything for him and Major Searles; they could ask nothing which

the thinker would not do in a lope. As for Colonel Miles, the fine-looking

man who led "ten thousand" in the great white battles, it was a distinction

to do exactly what he ordered -- every one did that; then why did he not

go to Major Searles's quarters, he kept asking himself. He was not afraid

of Colonel Miles or Captain Lewis or Major Searles or any officer, but

-- and the thought flashed, he was wary of the living eyes of the beloved

photograph. Before these he could not use his mind, hands, or feet; his

nerves shivered like aspen leaves in a wind, and the blood surged into

his head until he could see nothing with his eyes; cold chills played up

and down his spine; his hair crawled round under his sombrero, and he was

most thoroughly miserable, but some way he no longer felt contentment except

while undergoing this misery.

He lay on the blanket while his thoughts alternately fevered and chilled

his brain. So intense were his emotions that they did more than disorder

his mind: they took smart hold of his very body, gnawing and constricting

his vitals until he groaned aloud.

No wild beast which roamed the hills was less conscious, ordinarily,

of its bodily functions than Ermine. The machinery of a perfect physique

had always responded to the vital principle and unwound to the steady pull

of the spring of life, yet he found himself now stricken. It was not a

thing for the surgeon, and he gradually gave way before its steady progress.

His nature was a rich soil for the seeds of idealism which warm imagination

constantly sprinkled, and the fruits became a consuming passion.

His thoughts were burning him. Getting up from his bed, he took a kettle

and small axe, saddled his pony, and took himself off toward the river.

As he rode along he heard the Englishman call out to him, but he did not

answer. The pony trotted away, leaving the camp far behind, until he suddenly

came to a little prairie surrounded by cottonwoods, in the middle of which

were numbers of small wick-e-ups made by the Indians for sweat-baths. He

placed his blankets and ponchos over one, made a fire and heated a number

of rocks, divested himself of his clothing, and taking his pail of water

got inside, crouching while he dashed handfuls of water over the hot rocks.

This simple remedy would do more than cleanse the skin and was always resorted

to for common ills by the Indians. After Ermine came out he plunged into

the cold waters of the Yellowstone and dressed himself, but he did not

feel any better. He mounted and rode off, forgetting his axe, blankets,

and pail; such furnishings were unconsidered now. In response to a tremendous

desire to do something, he ran his pony for a mile, but that did not calm

the yearning.

"I feel like a piece of fly-blown meat," he said to himself. "I think

I will go to Saw-Bones and let him have a hack at me; I never was so sick

before." And to the cabin of the surgeon he betook himself.

That gentleman was fussing about with affairs of his own, when Ermine

entered.

"Say, doctor, give me some medicine."

"What's the matter with you?" asked the addressed, shoving his sombrero

to one side and looking up incredulously.

"Oh, I'm sick."

"Well, where are you sick?"

Ermine brushed his hair from off his forehead, slapped his leggings

with his quirt, and answered, "Sick all over kind of low fever, like a

man with a bullet in him."

"Bilious, probably." And the doctor felt his pulse and looked into his

bright, clear eyes.

"Oh, nonsense, boy you are not sick. I guess loafing around is bad for

you. The Colonel ought to give you a hundred miles with his compliments

to some one; but here is a pill which will cure you." Saying which, the

physician brought out his box containing wheat bread rolled into small

balls, that he always administered to cases which he did not understand

or to patients whom he suspected of shirking on "sick report."

Ermine swallowed it and departed.

The doctor tipped his sombrero forward and laughed aloud in long, cadenced

peals as he sorted his vials.

"Sick!" he muttered; "funny -- funny -- funny sick ! One could not kill

him with an axe. I guess he is sick of sitting round -- sick to be loping

over the wild plains. Humph -- sick!"

Ermine rode down the officers' row, but no one was to be seen. He pulled

his horse's head up before Major Searles's door, but instantly slapped

him with his whip and trotted on to his tent.

"If that fool Indian boy would only show himself," he thought; but the

Indian was not a fool, and did not. Again Ermine found himself lying on

his back, more discontented than ever. The day waned and the shadows on

the tent walls died, but still he lay. Ramon stuck his head in at the flaps.

"Well -- ah got your British man hees pony, Ermine -- trade twenty-five

dollar in goods for five pony."

" Oh, d---- the Englishman," was the response to this, whereat Ramon

took a good long stare at his friend and withdrew. He failed to understand

the abruptness, and went away wondering how Ermine could know that he had

gouged Mr. Harding a little on the trade. Still this did not explain; for

he had confidence in his own method of blinding his trail. He was a business

man and a moral cripple.

The sun left the world and Ermine with his gloomy thoughts.

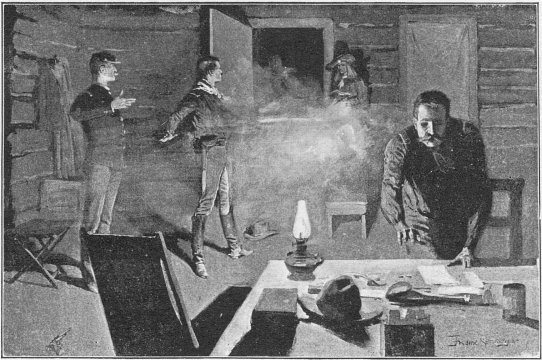

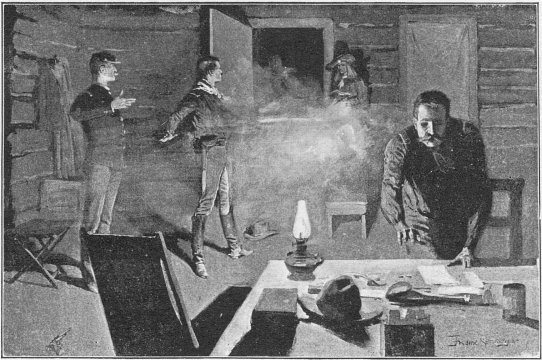

Late at night Captain Lewis sat at his desk writing letters, the lamp

spotting on the white disk of his hat, which shaded his face, while the

pale moonlight crept in through the open door. A sword clanked outside,

and with a knock the officer of the guard hurriedly entered.

"Say, Bill, I have your scout Ermine down by the guard-house, and he's

drunk. I didn't lock him up. Wanted to see you first. If I lock him up,

I am afraid he'll pull out on you when he comes to. What shall I do?"

"The devil you say Ermine drunk? Why, I never knew him to drink; it

was a matter of principle with him; often told me that his mentor, who

ever he was, told him not to."

"Well, he's drunk now, so there you are," said the officer.

"How drunk?"

"Oh, good and drunk."

"Can he walk?" Lewis queried.

"No; all he can do is lay on his back and shoot pretty thick Injun at

the moon."

"Does every one know of this?"

"No; Corporal Riley and Private Bass of Company K brought him up from

Wilmore's whiskey-shack, and they are sitting on his chest out back of

the guard-house. Come on," spoke the responsible one.

Lewis jumped up and followed. They quickly made their way to the spot,

and there Lewis beheld Ermine lying on his back. The moonlight cut his

fine face softly and made the aureole of his light hair stand away from

the ground. He moaned feebly, but his eyes were closed. Corporal Riley

and Private Bass squatted at his head and feet with their eyes fastened

on the insensible figure. Off to one side a small pile of Ermine's lethal

weapons shimmered. The post was asleep; a dog barked, and an occasional

cow-bell tinkled faintly down in the quarter master's corral.

"Gad! " gasped Lewis, as he too stooped down. "How did this happen,

Corporal?"

"Well, I suppose we might as well tell it as it is," Bass replied, indirectly

conscious of the loyalty he owed his brother sinner. "We ran the guard,

sir, and went down to Wilmore's, and when we got there, we found this feller

pretty far gone with drink. He had his guns out, and was talking Injun,

and he had Wilmore hiding out in the sage-brush. I beefed him under the

ear, and we took his guns away, sir. I didn't hurt him much; he was easy

money with his load, and then we packed him up here, and I told the officer

of the guard, sir."

"Well," said Lewis, finally, "make a chair of your hands and bring him

down to my quarters.quot;

The soldiers gathered up the limp form, while Lewis took the belt and

pistols.

"No use of reporting this?"

"No," answered the officer of the guard.

The men laid him out on the Captain's bed after partially disrobing

him, and started to withdraw.

"Go to your quarters, men, and keep your mouths shut; you will understand

it is best for you."

The two saluted and passed out, leaving the Captain pacing the floor,

and groping wildly for an explanation.

"Why, I have offered that boy a drink out of my own flask on campaign,

when we were cold enough and tired enough to make my old Aunt Jane weaken

on her blue ribbon; but he never did. That was good of the men to bring

him in, and smart of Welbote not to chuck him in the guard-house. Sailor's

sins! he'd never stand that; it would kill his pride, and he has pride,

this long-haired wild boy. He may tell me in the morning, but I am not

so sure of that. Laying down on his luck is not the way he plays it. I

don't doubt it was an accident, and maybe it will teach him a d---- good

lesson; he'll have a head like a hornets' nest to-morrow morning."

The Captain, after a struggle with the strange incident, sought his

couch, and when he arose next morning betook himself to Ermine's room.

He found him asleep amid the tangle of his wonderful hair, and he smiled

as he pictured the scout's surprise when he awoke; in fact, he pulled himself

together for a little amusement. A few remarks to reenforce the headache

would do more good than a long brief without a big 'exhibit A,' such as

would accompany the awakening.

The steady gaze of the Captain awoke the scout, and he opened his eyes,

which wandered about the room, but displayed no interest; they set themselves

on the Captain's form, but refused to believe these dreams, and closed

again. The Captain grinned and addressed the empty room: --

"How would you like to be a millionnaire and have that headache? Oh,

gee -- 'twould bust a mule's skull."

The eyes opened again and took more account of things; they began to

credit their surroundings. When the scene had assembled itself, Ermine

sat up on the bed, saying, "Where am I? what hit me?" and then he lay down

again. His dream had come true; he was sick.

"You are in my bed, so stay there, and you will come out all right.

You have been making the Big Red Medicine; the devil is pulling your hair,

and every time he yanks, he will say, 'John Ermine, don't do that again.'

Keep quiet, and you will get well." After saying which Lewis left the room.

All day long the young man lay on the bed; he was burning at the stake;

he was being torn apart by wild horses; the regimental band played its

bangiest music in his head; the big brass drum would nearly blow it apart;

and his poor stomach kept trying to crawl out of his body in its desperate

strife to escape Wilmore's decoction of high-wine. This lasted all day,

but by evening the volcano had blown itself out, when a natural sleep overcame

him.

Captain Lewis had the knowledge of certain magic, well enough known

in the army, to alleviate Ermine's condition somewhat, but he chose not

to use it; he wanted 'exhibit A' to wind up in a storm of fireworks.

As Ermine started out the next morning Lewis called, "Hey, boy, how

did you come to do it?"

Ermine turned a half-defiant and half-questioning front to Lewis and

tossed his matted hair. "I don't know, Captain; it all seems as though

I must have fallen off the earth; but I'm back now and think I can stay

here."

"Well, no one knows about it except myself, so don't say a word to any

one, and don't do it again -- sabe ?"

"You bet I won't. If the soldiers call that drowning their sorrows,

I would rather get along with mine."

Going to follow the dogs to-day, Lewis?" said Lieutenant Shockley, poking

his head in the half-open door.

"Yes, reckon I'll give this chair a vacation; wait a minute," and he

mauled the contents of his ditty-box after the manner of men and bears

when in search of trifles. A vigorous stirring is bound to upheave what

is searched for, so in due course the Captain dug up a snaffle-bit.

"I find my horse goes against this better than the government thing

-- when the idea is to get there and d---- formations."

"Well, shake yourself, Lewis; the people are pulling out."

"What, ahead of the scouts?" laughed the chief of them.

"Yes; and you know the line never retires on the scouts; so smoke up."

The orderly having changed the bits, the two mounted and walked away.

"'Spose this is for the Englishman. Great people these Englishmen go trotting

all over the earth to chase something ; anything will do from rabbits to

tigers, and niggers preferred," said Lewis.

"Must be a great deprivation to most Englishmen to have to live in England

where there is nothing to chase. I suppose they all have this desire to

kill something; a great hardship it must be," suggested Shockley.

"Oh, I think they manage," continued Lewis; "from what I understand

the rich and the great go batting about the globe after heads; the so-so

fellows go into the army and navy to take their chance of a killing, and

the lower orders have to find contentment in staying at home, where there

is no amusement but pounding each other."

"There goes your friend Ermine on that war-pony of his; well, he can

show his tail to any horse in cantonments. By the way, some one was telling

me that he carries a medicine-bag with him; isn't he a Christian?"

"Oh, I don't know. He reminds me of old Major Doyle of ours, who was

promoted out of us during the war, but who rejoined in Kansas and was retired.

You don't remember him? He was an Irishman and a Catholic; he had been

in the old army since the memory of man runneth not to the contrary, and

ploughed his way up and down all over the continent. And there was Major

Dunham you know him. He and Doyle had been comrades since youth; they had

fought and marched together, spilled many a noggin in each other's honor,

and who drew the other's monthly pay depended on the paste-boards. Old

Doyle came into post, one day, and had a lot of drinks with the fellows

as he picked up the social threads. Finally he asked: "'Un' phware is me

ole friend, Dunham? Why doesn't he come down and greet me with a glass?'

"Some one explained that old Dunham had since married, had joined the

church, and didn't greet any one over glasses any more.

"'Un' phwat church did he join?'

"Some one answered, the Universalist Church.

"'Ah, I see,' said Doyle, tossing off his drink, 'he's huntin' an aisy

ford.' So I guess that's what Ermine is doing."

They soon joined the group of mounted officers and ladies, orderlies,

and nondescripts of the camp, all alive with anticipations, and their horses

stepping high.

"Good morning, Mr. Harding; how do you find yourself?" called out Captain

Lewis.

"Fine -- fine, thank you."

"How are you mounted?"

Harding patted his horse's neck, saying: "Quite well a good beast; seems

to manage my weight, but I find this saddle odd. Bless me, I know there

is no habit in the world so strong as the saddle. I have the flat saddle

habit."

"What we call a rim-fire saddle," laughed Searles, who joined the conversation.

"Ah a rim-fire, do you call them? Well, do you know, Major, I should

say this saddle was better adapted to carrying a sack of corn than a man,"

rejoined Harding.

"Oh, you'll get along; there isn't a fence nearer than St. Paul except

the quartermaster's corral."

"I say, Searles," spoke Lewis, "there's the Colonel out in front --

happy as a boy out of school; glad there's something to keep him quiet;

we must do this for him every day, or he'll have us out pounding sage-brush."

"And there's the quartermaster with a new popper on his whip," sang

some voice.

"There is no champagne like the air of the high plains before the sun

burns the bubble out of it," proclaimed Shockley, who was young and without

any of the saddle or collar marks of life; "and to see these beautiful

women riding along say, Harding, if I get off this horse I'll set this

prairie on fire," and he burst into an old song: --

Now, ladies, good-by to each kind, gentle soul,

Though me coat it is ragged, me heart it is whole;

There's one sitting yonder I think wants a beau,

Let her come to the arms of young Billy Barlow."

And Shockley urged his horse to the side of Miss Katherine Searles.

Observing the manoeuvre, Captain Lewis poked her father in the ribs.

"I don't think your daughter wants a beau very much, Major; the youngsters

are four files deep around her now."

"'Tis youth, Bill Lewis; we've all had it once, and from what I observe,

they handle it pretty much as we used to."

"The very same. I don't see how men write novels or plays about that

old story; all they can do is to invent new fortifications for Mr. Hero

to carry before she names the day."

Lieutenant Shockley found himself unable to get nearer than two horses

to Miss Searles, so he bawled: "And I thought you fellows were hunting

wolves. I say, Miss Searles, if you ride one way and the wolf runs the

other, it is easy to see which will have the larger field. My money is

on you two to one. Who will take the wolf?"

Shockley

"Oh, Mr. Shockley, between you and this Western sun, I shall soon need

a new powder puff."

"Shall I challenge him?" called Bowles to the young woman.

"Please not, Mr. Bowles; I do not want to lose him." And every one greeted

Shockley derisively.

"Guide right!" shouted the last, putting his horse into a lope. Miss

Searles playfully slashed about with her riding-whip, saying, "Deploy,

gentlemen," and followed him. The others broke apart; they had been beaten

by the strategy of the loud mouth. Lieutenant Butler, however, permitted

himself the pleasure of accompanying Miss Searles; his determination could

not be shaken by these diversions; he pressed resolutely on.

"I think Butler has been hit over the heart," said one of the dispersed

cavaliers.

"You bet, and it is a disabling wound too. I wonder if Miss Searles

intends to cure him. When I see her handle her eyes, methinks, compadre,

she's a cruel little puss. I wouldn't care to be her mouse."

"But, fellows, she's pretty, a d---- pretty girl, hey!" ventured a serious

youngster. "You can bet any chap here would hang out the white flag and

come a-running, if she hailed him."

And so, one with another, they kept the sacred fire alight. As for that

matter, the aforesaid Miss Puss knew how her men valued the difficulties

of approach, which was why she scattered them. She proposed to take them

in detail. Men do not weaken readily before each other, but alone they

are helpless creatures, when the woman understands herself. She can then

sew them up, tag them, and put them away on various shelves, and rely on

them to stay there; but it requires management, of course.

"I say, Miss Searles, those fellows will set spring guns and bear traps

for me to-night; they will never forgive me."

"Oh, well, Mr. Shockley, to be serious, I don't care. Do you suppose

a wolf will be found? I am so bored." Which remark caused the eminent Lieutenant

to open his mouth very wide in imitation of a laugh, divested of all mirth.

"Miss Katherine Searles," he said, in mock majesty, "I shall do myself

the honor to crawl into the first badger-hole we come to and stay there

until you dig me out."

"Don't be absurd; you know I always bury my dead. Mr. Butler, do you

expect we shall find a wolf? Ah, there is that King Charles cavalier, Mr.

Ermine -- for all the world as though he had stepped from an old frame.

I do think he is lovely."

"Oh, bother that yellow Indian; he is such a nuisance," jerked Butler.

"Why do you say that? I find him perfectly new; he never bores me, and

he stood between me and that enraged savage."

"A regular play. I do not doubt he arranged it beforehand. However,

it was well thought out downright dramatic, except that the Indian ought

to have killed him."

"Oh, would you have arranged it that way if you had been playwright?"

"Yes," replied the bilious lover.

Shaking her bridle rein, she cried, "Come, Mr. Shockley, let us ride

to Ermine; at least you will admire him." Shockley enjoyed the death stroke

which she had administered to Butler, but saying to himself as he thought

of Ermine, "D---- the curly boy," and followed his charming and difficult

quarry. He alone had ridden true.

The independent and close-lipped scout was riding outside the group.

He never grew accustomed to the heavy columns, and did not talk on the

march a common habit of desert wanderers. But his eye covered everything.

Not a buckle or a horse-hair or the turn of a leg escaped him, and you

may be sure Miss Katherine Searles was detailed in his picture.

He had beheld her surrounded by the young officers until he began to

hate the whole United States army. Then he saw her dismiss the escort saving

only two, and presently she reduced her force to one. As she came toward

him, his blood took a pop into his head, which helped mightily to illumine

his natural richness of color. She was really coming to him. He wished

it, he wanted it, as badly as a man dying of thirst wants water, and yet

a whole volley of bullets would not disturb him as her coming did.

"Good morning, Mr. Ermine; you, too, are out after wolves, I see," sang

Katherine, cheerily.

"No, ma'm, I don't care anything about wolves; and why should I care

for them?"

"What are you out for then, pray?"

"Oh, I don't know; thought I would like to see you after wolves. I guess

that's why I am out," came the simple answer.

"Well, to judge by the past few miles I don't think you will see me

after them to-day."

"I think so myself, Miss Searles. These people ought to go back in the

breaks of the land to find wolves; they don't give a wolf credit for having

eyes."

"Why don't you tell them so, Mr. Ermine?" pleaded the young woman.

"The officers think they know where to find them ; they would not thank

me, and there might not be anywhere I would go to find them. It does not

matter whether we get one or none, anyhow," came Ermine's sageness.

"Indeed, it does matter. I must have a wolf."

"Want him alive or dead?" was the low question.

"What! am I to have one?"

"You are," replied the scout, simply.

"When?"

"Well, Miss Searles, I can't order one from the quartermaster exactly,

but if you are in a great hurry, I might go now."

"Mr. Ermine, you will surely kill me with your generosity. You have

offered me your scalp, your body, and now a wolf. Oh, by the way, what

did that awful Indian say to you? I suppose you have seen him since."

"Didn't say anything."

"Well, I hope he has forgiven you; but as I understand them, that is

not the usual way among Indians."

"No, Miss Searles, he won't forgive me. I'm a-keeping him to remember

you by."

"How foolish; I might give you something for a keepsake which would

leave better memories, do you not think so?"

"You might, if you wish to."

The girl was visibly agitated at this, coming as it did from her crude

admirer. She fumbled about her dress, her hair, and finally drew off her

glove and gave it to the scout, with a smile so sweet and a glance of the

eye which penetrated Ermine like a charge of buckshot. He took the glove

and put it inside of the breast of his shirt, and said, "I'll get the wolf."

Shockley was so impressed with the conversation that he was surprised

into silence, and to accomplish that phenomenon took a most powerful jolt,

as every one in the regiment knew. He could talk the bottom out of a nose-bag,

or put a clock to sleep. Ordinary verbal jollity did not seem at all adequate,

so he carolled a passing line:

"One little, two little, three little Injuns,

Four little, five little, six little Injuns,

Seven little, eight little, nine little Injuns,

Ten little Injun boys."

This came as an expiring burst which unsettled his horse though it relieved

him. Shockley needed this much yeast before he could rise again.

"Oh, Mr. Shockley, you must know Mr. Ermine."

"I have the pleasure, Miss Searles; haven't I, Ermine?"

The scout nodded assent.

"We were side by side when we rushed the point of that hill in the Sitting

Bull fight last fall; remember that, Ermine?"

"Yes, sir," said the scout; but the remembrance evidently did not cause

Ermine's E string to vibrate. Fighting was easier, freer; but altogether

it was like washing the dishes at home compared with the dangers which

now beset him.

Suddenly every one was whipping and spurring forward; the pack of greyhounds

were streaking it for the hills."Come on," yelled Shockley, "here's a run"

And that mercurial young man's scales tipped right readily from his heart

to his spurs.

"It's only a coyote, Miss Searles," said Ermine; but the young woman

spatted her horse with her whip and rode bravely after the flying Shockley.

Ermine's fast pony kept steadily along with her under a pull; the plainsman's

long, easy sway in the saddle was unconscious, and he never took his eyes

from the girl, now quite another person under the excitement.

Every one in the hunting-party was pumping away to the last ounce. A

pack of greyhounds make a coyote save all the time he can; they stimulate

his interest in life, and those who have seen a good healthy specimen burn

up the ground fully realize the value of passing moments.

"Oh, dear; my hat is falling off!" shrieked the girl.

"Shall I save it, Miss Searles?"

"Yes! yes! Catch it!" she screamed.

Ermine brought his flying pony nearer hers on the off side and reached

his hand toward the flapping hat, struggling at a frail anchorage of one

hat-pin, but his arm grew nerveless at the near approach to divinity.

"Save it! save it! " she called.

"Shall I?" and he pulled himself together.

Dropping his bridle-rein over the pommel of his saddle, standing in

his stirrups as steadily as a man in church, he undid the hat with both

hands. When he had released it and handed it to its owner, she heard him

mutter hoarsely, "My God!"

"Oh, Mr. Ermine, I hope the pin did not prick you."

"No, it wasn't the pin."

"Ah," she ejaculated barely loud enough for him to hear amid the rushing

hoof-beats.

The poor man was in earnest, and the idea drove the horses, the hounds,

and the coyote out of her mind, and she ran her mount harder than ever.

She detested earnest men, having so far in her career with the exception

of Mr. Butler found them great bores; but drive as she would, the scout

pattered at her side, and she dared not look at him.

These two were by no means near the head of the drive, as the girl's

horse was a stager, which had been selected because he was highly educated

concerning badger-holes and rocky hillsides.

Orderlies clattered behind them, and Private Patrick O'Dowd and Private

Thompson drew long winks at each other.

"Oi do be thinkin' the long bie's harse cud roon fasther eff the divil

was afther him. Faith, who'd roon away from a fairy?"

"The horse is running as fast as is wanted," said Thompson, sticking

his hooks into the Indian pony which he rode.

"Did yez obsarve the bie ramove the hat from the lady, and his pony

shootin' gravel into our eyes fit to smother?" shouted O'Dowd, using the

flat of his hand as a sounding-board to Thompson.

"You bet, Pat; and keeping the gait he could take a shoe off her horse,

if she wanted it done."

"They say seein's believin', but Oi'll not be afther tellin' the story

in quarters. Oi'm eaight year in the ahrmy, and Oi can lie whin it's convanient."

The dogs overhauled the unfortunate little wolf despite its gallant

efforts, and it came out of the snarling mass, as some wag had expressed

it, "like a hog going to war -- in small pieces." The field closed up and

dismounted, soldier fashion, at the halt.

"What's the matter with the pony to-day, Ermine? Expected you'd be ahead

of the wolf at least," sang out Lewis.

"I stopped to pick up a hat," he explained; but Captain Lewis fixed

his calculating eye on his man and bit his mustache. Events had begun to

arrange themselves; that drunken night and Ermine's apathy toward the Englishman's

hunting-party and he had stopped to pick up her hat -- oho!

Without a word the scout regained his seat and loped away toward the

post, and Lewis watched him for some time, in a brown study; but a man

of his years often fails to give the ardor of youth its proper value, so

his mind soon followed more natural thoughts.

"Your horse is not a very rapid animal, I observe, Miss Searles," spoke

Butler.

"Did you observe that? I did not notice that you were watching me, Mr.

Butler."

"Oh, I must explain that in an affair of this kind I am expected to

sustain the reputation of the cavalry. I forced myself to the front."

"Quite right. I kept the only man in the rear, who was capable of spoiling

your reputation; you are under obligations to me."

"That wild man, you mean. He certainly has a wonderful pony, but you

need not trouble about him if it is to please me only."

"I find this sun becoming too insistent; I think I will go back," said

Katherine Searles. Many of the women also turned their horses homeward,

leaving only the more pronounced types of sportsmen to search for another

wolf.

"Having sustained the cavalry, I'll accompany you, Katherine."

"Miss Searles, please!" she said, turning to him, and the little gem

of a nose asserted itself.

"Oh, dear me! What have I done? You permitted me to call you Katherine

only last night."

"Yes, but I do not propose to divide my friendship with a nasty little

gray wolf which has been eaten up alive."

The officer ran his gauntlet over his eyes.

"I am such a booby. I see my mistake, Miss Searles, but the idea you

advance seems so ridiculous -- to compare yourself with a wolf."

"Oh, I say, Miss Searles," said Shockley, riding up, "may I offer you

one of my gauntlets? The sun, I fear, will blister your bare hand."

"No, indeed." And Butler tore off a glove, forcing it into her hand.

She could not deny him, and pulled it on. "Thank you; I lost one of mine

this morning."

Then she turned her eyes on Mr. Shockley with a hard little expression,

which sealed him up. He was prompt to feel that the challenge meant war,

and war with this girl was the far-away swing of that gallant strategic

pendulum.

"Yes," Shockley added, "one is apt to drop things without noting them,

in a fast rush. I dropped something myself this morning."

"Pray what was it, Mr. Shockley?"

"It was an idea," he replied with a shrug of the shoulders.

"An idea?" laughed she, appreciating Shockley's discretion. "I hope

you have more of them than I have gloves."

"I have only one," he sighed.

"Are all soldiers as stupid as you are, my dear sir?"

"All under thirty, I am sorry to say," and this from Shockley too. Miss

Searles applied the whip; but go as she would, the two officers did not

lose again the idea, but kept their places beside her.

"You are not very steady under fire," laughed Shockley.

"You are such an absurd person."

"I may be a blessing in disguise."

"You may be; I am unable to identify you."

"The chaperon is waving her whip at us, Miss Searles," cautioned Butler.

"Private O'Dowd is my chaperon, and he can stand the pace," she replied.

The young woman drove on, leaving a pall of dust behind, until the little

party made the cantonment and drew rein in front of the Searleses' quarters.

Giving her hand to the orderly, she dismissed her escort and disappeared.

"Well, Katherine," said Mrs. Searles, "did you enjoy your ride?"

"Yes, mother, but my horse is such an old poke I was nowhere in the

race."