Volume 1896

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the

advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/ermine.htm

John Ermine of the Yellowstone

Frederic Remington

Part 1: Chapters I - X

Continued

in Part 2

Author(s)

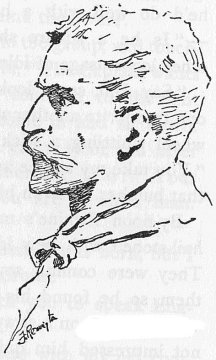

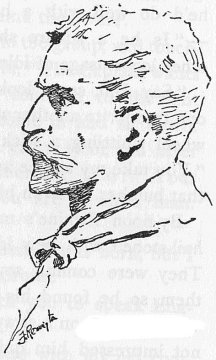

Frederic Remington (1861-1909): Born in Canton, N.Y. in 1861, he studied

at the Yale School of Fine Arts from 1878-80. After the death of his father

he went west and worked as a sheep-herder, cow-puncher, storekeeper, cook

and stockman, and sketched in his free time. Returning to New York he began

an illustrious career as artist and illustrator that took him to Russia,

Germany and North Africa, and to Cuba, as a war correspondent during the

Spanish-American War. He died suddenly in Ridgefield, Conn. in 1909, of

complications arising from appendicitis. More about Remington here

Link to Tarzan of the Apes

This story tells of a white male infant raised by Native Americans, who

returns to civilization but ultimately is neither at home among 'whites'

or Indians. As an archetype of the wild-man in civilised society, John

Ermine is mentioned as a thematic precursor of Tarzan by

-

John Seelye. 1990. "Introduction" p. vii-xxviii, In Tarzan of the Apes

New York: Penguin Books.

Edition(s) used

-

Frederic Remington. 1902. John Ermine of the Yellowstone. New York:

Macmillan.

Text converted to HTML from Internet

Archive

-

illustrations by the author from 1967 Gregg Press (Ridgewood, NJ) rpt.

Modifications to the text

-

Chapter titles placed in Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

John Ermine of the Yellowstone

John Ermine

ne fine morning

in the fall of '64 Alder Gulch rolled up its shirt sleeves and fell to

the upheaving, sluicing, drifting, and cradling of the gravel. It did not

feel exactly like old-fashioned everyday work to the muddy, case-hardened

diggers. Each man knew that by evening he would see the level of dust rise

higher in his long buckskin gold-bags. All this made for the day when he

could retire to the green East and marry some beautiful girl --thereafter

having nothing to do but eat pie and smoke fragrant cigars in a basking

sunshine of no-work. Pie up at Kustar's bake-shop was now one dollar a

pie, and a pipe full of molasses and slivers was the best to be had in

the market. Life was hard at Alder in those days -- it was practical; and

when its denizens became sentimental, it took these unlovely forms, sad

to relate.

ne fine morning

in the fall of '64 Alder Gulch rolled up its shirt sleeves and fell to

the upheaving, sluicing, drifting, and cradling of the gravel. It did not

feel exactly like old-fashioned everyday work to the muddy, case-hardened

diggers. Each man knew that by evening he would see the level of dust rise

higher in his long buckskin gold-bags. All this made for the day when he

could retire to the green East and marry some beautiful girl --thereafter

having nothing to do but eat pie and smoke fragrant cigars in a basking

sunshine of no-work. Pie up at Kustar's bake-shop was now one dollar a

pie, and a pipe full of molasses and slivers was the best to be had in

the market. Life was hard at Alder in those days -- it was practical; and

when its denizens became sentimental, it took these unlovely forms, sad

to relate.

Notwithstanding the hundreds who toiled in the gulches, Virginia City

itself held hurrying crowds, Mormon freighters, pack trains, ponies, dirty

men off the trails, wan pilgrims, Indians, Chinese, and almost everything

else not angelic.

Into this bustle rode Rocky Dan, who, after dealing faro all night at

the "Happy Days" shebang, had gone for a horseback ride through the hills

to brighten his eyes and loosen his nerves. Reining up before this place,

he tied his pony where a horse-boy from the livery corral could find it.

Striding into that unhallowed hall of Sheol, he sang out, "Say, fellers,

I've just seen a thing out in the hills which near knocked me off'en my

horse. You couldn't guess what it was nohow. I don't believe half what

I see and nothin' what I read, but it's out thar in the hills, and you

can go throw your eyes over it yourselves."

"What? a new thing, Dan? No! No! Dan, you wouldn't come here with anything

good and blurt it out," said the rude patrons of the "Happy Days" mahogany,

vulturing about Rocky Dan, keen for any thing new in the way of gravel.

"I gamble it wa'n't a murder -- that wouldn't knock you off'en your

horse, jus' to see one -- hey, Dan?" ventured another.

"No, no," vouched Dan, laboring under an excitement ill becoming a faro-dealer.

Recovering himself, he told the bartender to 'perform his function.' The

"valley tan" having been disposed of, Dan added: --

"It was a boy!"

"Boy -- boy -- a boy?" sighed the crowd, setting back their 'empties.'

"A boy ain't exactly new, Dan," added one.

" No, that's so," he continued, in his unprofessional perplexity, "but

this was a white boy."

"Well, that don't make him any newer," vociferated the crowd.

"No, d--- it, but this was a white boy out in that Crow Injun camp,

with yeller hair braided down the sides of his head, all the same Injun,

and he had a bow and arrer, all the same Injun; and I said, 'Hello, little

feller,' and he pulled his little bow on me, all the same Injun. D--- the

little cuss, he was about to let go on me. I was too near them Injuns,

anyhow, but I was on the best quarter horse in the country, as you know,

and willin' to take my chance. Boys, he was white as Sandy McCalmont there,

only he didn't have so many freckles." The company regarded the designated

one, who promptly blushed, and they gathered the idea that the boy was

a decided blonde.

"Well, what do you make of it, anyhow, Dan?"

"What do I make of it? Why, I make of it that them Injuns has lifted

that kid from some outfit, and that we ought to go out and bring him in.

He don't belong there, nohow, and that's sure."

"That's so," sang the crowd as it surged into the street; "let's saddle

up and go and get him. Saddle up! saddle up!"

The story blew down the gulch on the seven winds. It appealed to the

sympathies of all white men, and with double force to their hatred of the

Indians. There was no man at Alder Gulch, -- even the owners of squaws,

-- and they were many, who had not been given cause for this resentment.

Business was suspended. Wagoners cut out and mounted team-horses; desperadoes,

hardened roughs, trooped in with honest merchants and hardy miners as the

strung-out cavalcade poured up the road to the plateau, where the band

of Crows had pitched their tepees.

"Klat-a-way! Klat-a-way!" shouted the men as they whipped and spurred

up the steeps. The road narrowed near the top, and here the surging horsemen

were stopped by a few men who stood in the middle waving and howling "Halt!"

The crowd had no definite scheme of procedure at any time, it was simply

impelled forward by the ancient war-shout of A rescue! A rescue!

The blood of the mob had mounted high, but it drew restive rein before

a big man who had forced his pony up on the steep hillside and was speaking

in a loud, measured, and authoritative voice.

The riders felt the desire for council; the ancient spirit of the witenagemote

came over them. The American town meeting, bred in their bones and burned

into their brains, made them listen to the big temporary chairman with

the yellow lion's mane blowing about his head in the breeze. His horse

did not want to stand still on the perilous hillside, but he held him there

and opened.

The Chairman

"Gentlemen, if this yar outfit goes a-chargin' into that bunch of Injuns,

them Injuns aforesaid is sure goin' to shoot at us, and we are naturally

goin' to shoot back at them. Then, gentlemen, there will be a fight, they

will get a bunch of us, and we will wipe them out. Now, our esteemed friend

yer, Mr. Chick-chick, savvies Injuns, as you know, he bein' somewhat their

way hisself -- allows that they will chill that poor little boy with a

knife the first rattle out of the box. So, gentlemen, what good does it

all do? Now, gentlemen, I allows if you all will keep down yer under the

hill and back our play, Chick-chick and me will go into that camp and get

the boy alive. If these Injuns rub us out, it's your move. All what agrees'

to this motion will signify it by gettin' down off'en their horses."

Slowly man after man swung to the ground. Some did not so readily agree,

but they were finally argued off their horses. Whereat the big chairman

sang out: "The ayes have it. Come on, Mr. Chick-chick."

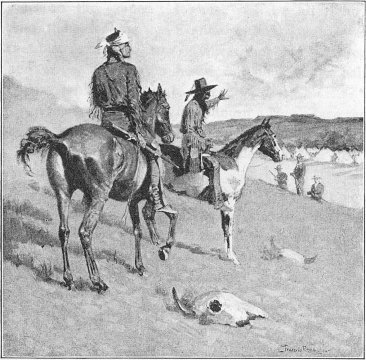

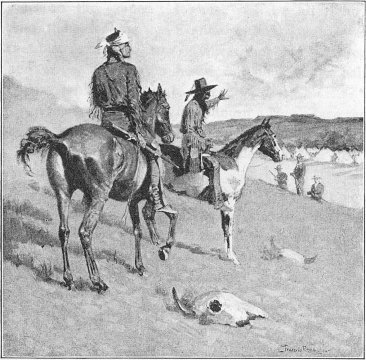

These two rode up the hill and over the mesa, trotting along as they

talked. "Now, Chick-chick, I don't know a heap about Injuns. The most that

I have seen of them was over the sights of a rifle. How are we goin' at

this? Do you habla Crow lingo, Señor?"

"No," replied that much mixed-blooded man, "I no cumtux Crow,

but I make the hand talk, and I can clean up a ten-ass Chinook;

all you do is to do nothing, you no shake hands, you say nothing, until

we smoke the pipe, then you say 'How?' and shake hands all same white man.

You hang on to your gun -- suppose they try take it away -- well, den,

icta-nica-ticki,

you shoot! Then we are dead." Having laid his plan of campaign before his

brother in arms, no more was said. History does not relate what was thought

about it.

They arrived in due course among the tepees of a small band of Crows.

There were not probably a hundred warriors present, but they were all armed,

horsed, and under considerable excitement. These Crows were at war with

all the other tribes of the northern plains, but maintained a truce with

the white man. They had very naturally been warned of the unusual storm

of horsemen bearing in their direction, and were apprehensive concerning

it. They scowled at the chairman and Mr. Chick-chick, who was an Oregon

product, as they drew up. The latter began his hand-language, which was

answered at great length. He did not at once calm the situation, but was

finally invited to smoke in the council lodge. The squaws were pulling

down the tepees; roping, bundling, screaming, hustling ponies, children,

and dogs about, unsettling the statesmen's nerves mightily as they passed

the pipe. The big chairman began to fancy the Indians he had seen through

the sights more than these he was regarding over the pipe of peace. Chick-chick

gesticulated the proposition that the white papoose be brought into the

tent, where he could be seen.

The Indians demurred, saying there was no white boy -- that all in the

camp were Crows. A young warrior from outside broke into their presence,

talking in a loud tone. An old chief looked out through the entrance-flap,

across the yellow plains. Turning, he inquired what the white horsemen

were doing outside.

He was told that they wanted the white boy; that the two white chiefs

among them would take the boy and go in peace, or that the others would

come and take him in war. Also, Chick-chick intimated that he must klat-a-way.

The Indians made it plain that he was not going to klat-a-way; but

looking abroad, they became more alarmed and excited by the cordon of whites

about them.

"When the sun is so high," spoke Chick-chick, pointing, and using the

sign language, "if we do not go forth with the boy, the white men will

charge and kill all the Crows. One white boy is not worth that much."

After more excitement and talk, a youngish woman came, bearing a child

in her arms, which was bawling and tear-stained, -- she vociferating wildly

the time. Taking the unmusical youngster by the arm, the old chief stood

him before Chick-chick. The boy was near nine years of age, the men judged,

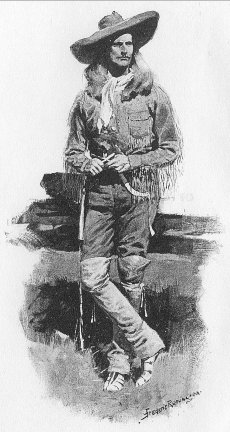

white beyond question, with long, golden hair braided, Indian fashion,

down the sides of his head. He was neatly clothed in dressed buckskins,

fringed and beaded, and not naked or half naked, as most Indian boys are

in warm weather. It was not possible to tell what his face looked like

in repose, for it was kneaded into grotesque lumps by his cries and wailing.

"He is a Crow; his skin is white, but his heart is Absaroke. It makes

us bleed to see him go; our women will mourn all this snow for him, but

to save my band I give him to you. Take him. He is yours."

Chick-chick lifted the child in his arms, where the small cause of all

the turmoil struggled and pulled hair until he was forced to hold him out

at arm's length. Mounting, they withdrew toward their friends. The council

tepee fell in the dirt a dozen squaws tugging at its voluminous folds.

The small hostage was not many yards on his way toward his own kind before

the Indian camp moved off toward the mountains, urging their horses with

whip and lance. This movement was accelerated by a great discharging of

white men's guns, who were supposed to be sacrificing the little white

Crow to some unknown passions; whereas, they were merely celebrating the

advent of the white child unharmed. He was indeed unharmed as to body,

but his feelings had been torn to shreds. He added his small, shrill protesting

yells to the general rejoicing.

Chick-chick, or Chickens, as the miners often called him, had not entered

the expedition because of his love for children, or the color of this one

in particular; so, at the suggestion of the chairman, it was turned over

to a benevolent saloon-keeper, who had nine notches in his gun, and a woman

with whom he abided. "Gold Nugget," as he was promptly named by the diggers

and freighters, was supposed to need a woman, as it was adjudged that only

such a one could induce him to turn off the hot water and cease his yells.

The cavalcade reached town, to find multitudes of dirt-begrimed men

thronging the streets waiting for what sensation there was left in the

affair. The infant had been overcome by his exertions and was silent. They

sat him on the bar of his godfather's saloon, while the men shouldered

their brawny way through the crowd to have a look at him the lost white

child in the Indian dress. Many drinks and pistol shots were offered up

in his honor, and he having recovered somewhat, resumed his vocal protests.

These plaints having silenced the crowd, it was suggested by one man who

was able to restrain his enthusiasm, that the kid ought to be turned over

to some woman before he roared his head off.

Acting on this suggestion, the saloon-keeper's female friend was given

charge. Taking him to her little house back of the saloon, the child found

milk and bread and feminine caresses to calm him until he slept. It was

publicly proclaimed by the nine-notch saloon-keeper that the first man

who passed the door of the kid's domicile would be number ten to his gun.

This pronunciamiento insured much needed repose to Gold Nugget during the

night.

In the morning he was partially recovered from fears and tears. The

women patted his face, fed him to bursting, fingered the beautiful plaits

of his yellow hair, and otherwise showed that they had not surrendered

all their feminine sensibilities to their tumultuous lives. They spoke

to him in pleading voices, and he gurgled up his words of reply in the

unknown tongue. The saloon-keeper's theory that it would be a good thing

to set him up on the bar some more in order to keep trade, was voted both

inhuman and impracticable by the women. Later in the day a young man managed

to get on the youngster's blind side, when by blandishments he beguiled

him on to his pony in front of him. Thus he rode slowly through the streets,

to the delight of the people, who responded to Gold Nugget's progress by

volley and yell. This again frightened him, and he clung desperately to

his new friend, who by waving his arm stilled the tempest of Virginia City's

welcome, whereat the young man shouted, "Say -- do you think this kid is

runnin' for sheriff?"

The Gulch voted the newcomer the greatest thing that ever happened;

took him into partnership, speculated on his previous career, and drank

his health. Above all they drank his health. Unitedly they drank to his

weird past, his interesting present, and to his future life and happiness,

far into the night. It was good for business, said the saloon-keepers one

to another.

On one of the same mountain winds which had heralded his coming was

borne down the Gulch next morning the tragic words, "The kid has gone!"

"Gone?" said the miners; "gone whar?"

Alder promptly dropped its pick, buckled on its artillery, and assembled

before the nine-notch man.

"Where has the kid gone?" it demanded.

His woman stood beside the bar, wild-eyed and dishevelled. "I don't

know, gentlemen -- I don't have an idea. He was playing by the door of

my shack last evening. I went in the house for a minute, and when I came

out he was gone. I yelled, and men came, but we could not find him hide

or hair."

"If any man has got that kid away from me, mind you this now, -- he

will see me through the smoke," spoke nine-notch, as he rolled his eye

malevolently for a possible reply.

Long search and inquiry failed to clear matters. The tracks around the

house shed no new light. The men wound their way to their cabins up and

down the Gulch, only answering inquiries by, "The kid is gone."

or many days the

Absaroke trotted and bumped along, ceaselessly beating their ponies' sides

with their heels, and lashing with their elk-horn whips. With their packs

and travoix they could not move fast, but they made up for this by long

hours of industrious plodding. An Indian is never struck without striking

back, and his counter always comes when not expected. They wanted to manoeuvre

their women and children, so that many hills and broad valleys would lie

between them and their vengeance when it should be taken. Through the deep

cañons, among the dark pine trees, out across the bold table-lands,

through the rivers of the mountains, wound the long cavalcade, making its

way to the chosen valley of Crowland, where their warriors mustered in

numbers to secure them from all thought of fear of the white men.

or many days the

Absaroke trotted and bumped along, ceaselessly beating their ponies' sides

with their heels, and lashing with their elk-horn whips. With their packs

and travoix they could not move fast, but they made up for this by long

hours of industrious plodding. An Indian is never struck without striking

back, and his counter always comes when not expected. They wanted to manoeuvre

their women and children, so that many hills and broad valleys would lie

between them and their vengeance when it should be taken. Through the deep

cañons, among the dark pine trees, out across the bold table-lands,

through the rivers of the mountains, wound the long cavalcade, making its

way to the chosen valley of Crowland, where their warriors mustered in

numbers to secure them from all thought of fear of the white men.

The braves burned for vengeance on the white fools who dug in the Gulch

they were leaving behind, but the yellow-eyed people were all brothers.

To strike the slaves of the gravel-pits would be to make trouble with the

river-men, who brought up the powder and guns in boats every green-grass.

The tribal policy was against such a rupture. The Crows, or Sparrowhawks

as they called themselves, were already encompassed by their enemies, and

only able by the most desperate endeavors to hold their own hunting-grounds

against the Blackfeet, Sioux, and Cheyennes. Theirs was the pick and choosing

of the northern plains. Neither too hot nor too cold, well watered and

thickly grassed on the plains, swarming with buffalo, while in the winter

they could retire to the upper valleys of the Big Horn River, where they

were shut in by the impassable snow-clad mountains from foreign horse thieves,

and where the nutritious salt-weed kept their ponies in condition. Like

all good lands, they could only be held by a strong and brave people, who

were made to fight constantly for what they held. The powder and guns could

only be had from the white traders, so they made a virtue of necessity

and held their hand.

Before many days the squaw Ba-cher-hish-a rode among the lodges with

little White Weasel sitting behind her, dry-eyed and content.

Alder had lost Gold Nugget, but the Indians had White Weasel -- so things

were mended.

His foster-mother -- the one from whom the chief had taken him had stayed

behind the retreating camp, stealing about unseen. She wore the wolf-skin

over her back, and in those days no one paid any attention to a wolf. In

the dusk of evening she had lain near the shack where her boy was housed,

and at the first opportunity she had seized him and fled. He did not cry

out when her warning hiss struck native tones on his ear. Mounting her

pony, she had gained the scouts, which lay back on the Indian trail. The

hat-weavers (white men) should know White Weasel no more.

The old men Nah-kee and Umbas-a-hoos sat smoking over their talk in

the purple shade of a tepee. Idly noting the affairs of camp, their eyes

fell on groups of small urchins, which were scampering about engaging each

other in mimic war. They shot blunt-headed arrows, while other tots returned

the fire from the vantage of lariated ponies or friendly tepees. They further

observed that little White Weasel, by his activity, fierce impulse, and

mental excellence, was admittedly leading one of these diminutive war-parties.

He had stripped off his small buckskin shirt, and the milk-white skin glared

in the sunlight; one little braid had become undone and flowed in golden

curls about his shoulders. In childish screams he urged his group to charge

the other, and running forth he scattered all before his insistent assault.

"See, brother," spoke Nah-kee, "the little white Crow has been struck

in the face by an arrow, but he does not stop."

"Umph he will make a warrior," replied the other, his features relaxing

into something approaching kindliness. The two old men understood what

they saw even if they had never heard of the "Gothic self-abandonment"

which was the inheritance of White Weasel. "He may be a war-chief -- he

leads the boys even now, before he is big enough to climb up the fore leg

of a pony to get on its back. The arrow in his face did not stop him. These

white men cannot endure pain as we do; they bleat like a deer under the

knife. Do you remember the one we built the fire on three grasses ago over

by the Big Muddy when Eashdies split his head with a battle-axe to stop

his noise? Brother, little White Weasel is a Crow."

A Crow

"It is so," pursued the other veteran; "these yellow-eyes are only fit

to play badger in a gravel-pit or harness themselves to loaded boats, which

pull powder and lead up the long river. They walk all one green-grass beside

their long-horned buffalo, hauling their tepee wagons over the plains.

If it were not for their medicine goods, we would drive them far away."

"Yes, brother, they are good for us. If we did not have their powder

and guns, the Cut-Throats [Sioux] and the Cut-Arms [Cheyennes] would soon

put the Absaroke fires out. We must step carefully and keep our eyes open

lest the whites again see White Weasel; and if these half-Indian men about

camp talk to the traders about him, we will have the camp soldiers beat

them with sticks. The white traders would take our powder away from us

unless we gave him to them."

"We could steal him again, brother."

"Yes, if they did not send him down the long river in a boat. Then he

would go so far toward the morning that we should never pass our eyes over

him again on this side of the Spiritland. We need him to fill the place

of some warrior who will be struck by the enemy."

Seeing the squaw Ba-cher-hish-a passing, they called to her and said:

"When there are any white men around the camps, paint the face of your

little son White Weasel, and fill his hair with wood ashes. If you are

careful to do this, the white men will not notice him; you will not have

to part with him again."

"What you say is true," spoke the squaw, "but I cannot put black ashes

in his eyes." She departed, nevertheless, glorious with the new thought.

Having fought each other with arrows until it no longer amused them,

the foes of an idle hour ran away together down by the creek, where they

disrobed by a process neatly described by the white men's drill regulations,

which say a thing shall be done in "one time and two motions."

White Weasel was more complicated than his fellows by reason of one

shirt, which he promptly skinned off. "See the white Crow," gurgled a small

savage, as every eye turned to our hero. "He always has the war-paint on

his body. He is always painted like the big men when they go to strike

the enemy -- he is red all over. The war-paint is in his skin."

"Now, let us be buffalo," spoke one, answered by others, "Yes, let us

be buffalo." Accordingly, in true imitation of what to them was a familiar

sight, they formed in line, White Weasel at the head as usual. Bending

their bodies forward and swinging their heads, they followed down to the

water, throwing themselves flat in the shallows. Now they were no longer

buffalo, but merely small boys splashing about in the cool water, screaming

incoherently and as nearly perfectly happy as nature ever intended human

beings to be. After a few minutes of this, the humorist among them, the

ultra-imaginative one, stood up pointing dramatically, and, simulating

fear, yelled, "Here comes the bad water monster," whereat with shrill screams

and much splashing the score of little imps ran ashore and sat down, grinning

at their half-felt fear. The water monster was quite real to them. Who

could say one might not appear and grab a laggard?

After this they ran skipping along the river bank, quite naked, as purposeless

as birds, until they met two old squaws dipping water from the creek to

carry home. With hue and cry they gathered about them, darting like quick-motioned

wolves around worn-out buffalo. "They are buffalo, and we are wolves,"

chorussed the infant band; "bite them! blind them! We are wolves! we will

eat them!" They plucked at their garments and threw dirt over them in childish

glee. The old women snarled at their persecutors and caught up sticks to

defend themselves. It was beginning to look rather serious for the supposed

buffalo, when a young warrior came riding down, his pony going silently

in the soft dirt. Comprehending the situation, and being fairly among them,

he dealt out a few well-considered cuts with his pony-whip, which changed

the tune of those who had felt its contact. They all ran off, some holding

on to their smarts -- scattering away much as the wolves themselves might

have done under such conditions.

Indian boys are very much like white boys in every respect, except that

they are subject to no restraint, and carry their mischievousness to all

bounds. Their ideas of play being founded on the ways of things about them,

they are warriors, wild animals, horses, and the hunters, and the hunted

by turns. Bands of these little Crows scarcely past toddling ranged the

camp, keeping dogs, ponies, and women in a constant state of unrest. Occasional

justice was meted out to them with a pony-whip, but in proportions much

less than their deserts.

Being hungry, White Weasel plodded home to his mother's lodge, and finding

a buffalo rib roasting near the fire he appropriated it. It was nearly

as large as himself, and when he had satisfied his appetite, his face and

hands were most appallingly greased. Seeing this, his mother wiped him

off, but not as thoroughly as his condition called for, it must be admitted.

Falling back on a buffalo robe, little Weasel soon fell into a deep slumber,

during which a big dog belonging to the tent made play to complete the

squaw's washing, by licking all the grease from his face and hands.

In due course he arose refreshed and ready for more mischief. The first

opportunity which presented itself was the big dog, which was sleeping

outside. "He is a young pony; I will break him to bear a man," said Weasel

to himself. Straight way he threw himself on the pup, grasping firmly with

heel and hand. The dog rose suddenly with a yell, and nipped one of Weasel's

legs quite hard enough to bring his horse-breaking to a finish with an

answering yell. The dog made off, followed by hissing imprecations from

Ba-cher-hish-a, who rubbed the little round leg and crooned away his tears.

He was not long depressed by the incident.

Now all small Indian boys have a regard for prairie-dog or marmot's

flesh, which is akin to the white boy's taste for candy balls and cream

paste. In order to satisfy it the small Indian must lie out on the prairie

for an hour under the broiling sun, and make a sure shot in the bargain.

The white boy has only to acquire five cents, yet in the majority of cases

that too is attended by almost overwhelming difficulties.

With three other boys White Weasel repaired to the adjoining dog-town,

and having located from cover a fat old marmot whose hole was near the

outskirts of the village, they each cut a tuft of grease-weed. Waiting

until he had gone inside, they ran forward swiftly and threw themselves

on the ground behind other dog mounds, putting up the grease-weed in front

of themselves. With shrill chirping, all the marmots of this colony dived

into their holes and gave the desert over to silence. After a long time

marmots far away from them came out to protest against the intrusion. An

old Indian warrior sitting on a near-by bluff, nursing morose thoughts,

was almost charmed into good nature by the play of the infant hunters below

him. He could remember when he had done this same thing -- many, many grasses

ago. More grasses than he could well remember.

The sun had drawn a long shadow before the fat marmot showed his head

above the level of his intrenchments his fearful little black eyes set

and his ears straining. Three other pairs of black eyes and one pair of

blue ones snapped at him from behind the grease-weed. There followed a

long wait, after which the marmot jumped up on the dirt rim which surrounded

his hole, and there waited until his patience gave out. With a sharp bark

and a wiggling of his tail he rolled out along the plain, a small ball

of dusty fur. To the intent gaze of the nine-year-olds he was much more

important than can be explained from this view-point.

Having judged him sufficiently far from his base, the small hunters

sprang to their knees, and drove their arrows with all the energy of soft

young arms at the quarry. The marmot made a gallant race, but an unfortunate

blunt-head caught him somewhere and bowled him over. Before he could recover,

the boys were upon him, and his stage had passed.

Carrying the game and followed by his companions, Weasel took it home

to his foster-mother, who set to skinning it, crooning as she did in the

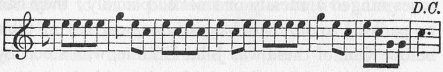

repeated sing-song of her race:

"My son is a little hunter,

My son is a little hunter,

Some day the buffalo will fear him,

Some day the buffalo will fear him,

Some day the buffalo will fear him,"

and so on throughout the Indian list until the marmot was ready

for cooking.

So ran the young life of the white Crow. While the sun shone, he chased

over the country with his small fellows, shooting blunt arrows at anything

living of which they were not afraid. No one corrected him; no one made

him go to bed early; no one washed him but the near-by brook; no one bothered

him with stories about good little boys; in fact, whether he was good or

bad had never been indicated to him. He was as all Crow boys are no better

and no worse. He shared the affections of his foster-parents with several

natural offspring, and shared in common, though the camp took a keen interest

in so unusual a Crow. Being by nature bright and engaging, he foraged on

every camp kettle, and made the men laugh as they lounged in the afternoon

shade, by his absurd imitations of the war and scalp dances, which he served

up seriously in his infant way.

Any white man could see at a glance that White Weasel was evolved from

a race which, however remote from him, got its yellow hair, fair skin,

and blue eyes amid the fjords, forests, rocks, and ice-floes of the north

of Europe. The fierce sun of lower latitudes had burned no ancestor of

Weasel's; their skins had been protected against cold blasts by the hides

of animals. Their yellow hair was the same as the Arctic bear's, and their

eyes the color of new ice. Little Weasel's fortunes had taken him far afield.

He was born white, but he had a Crow heart, so the tribesmen persuaded

themselves. They did not understand the laws of heredity. They had never

hunted those.

With the years White Weasel spindled up into a youth whose legs quite naturally

fitted around the barrel of a horse. He no longer had to climb up the fore

leg of a camp-pony, but could spring on to those that ran in his father's

herd and maintain his position there.

Having observed this, one night his foster-father said to him: "You

are old enough, my son, to be trusted with my ponies out in the hills.

You must begin to study the ponies, or you will never be able to take or

hold any of your own. Not to have horses is not to hunt buffalo or go to

the enemy, and not to have a wife. Go, then, when the morning comes, with

your brother, and watch my herd. See that they feed safely; see that by

evening they come to the lodges. You are old enough now to wear the loin-cloth;

you must begin to be a man. You will never find your shadow-self here among

the noisy lodges; it will only come to you out in the quiet of the hills.

The Bad Spirits always have their arms out to clutch you when you are asleep

in the night; as you ride in the shadows; when you ford the waters, --

they come in the wind, the rain, the snow; they point the bullet and the

battle-axe to your breast, and they will warn the Sioux when you are coming

after their ponies. But out in the hills the Sak-a-war-te

(1):

will send some bird or some little wolf to you as his friend; in some way

he will talk to you and give a sign that will protect you from the Bad

Gods. Do not eat food or drink water; pray to him, and he will come to

you; if he does not, you will be lost. You will never see the Spiritland

when your body lies flat on the ground and your shadow has gone."

After saying this, his father's pipe died out, the mother put no more

dry sticks on the fire, the shapes along the lodge walls died away in the

gloom, and left the youth awake with a new existence playing through his

brain. He was to begin to be a man. Already he had done in play, about

the camp, the things which the warriors did among the thundering buffalo

herds; he had imitated the fierce nervous effort to take the enemy's life

in battle and the wolfish quest after ponies. He had begun to take notice

of the great difference between himself and the girls about the camp; he

had a meaning which they did not; his lot was in the field.

Before the sun rose he was one of the many noisy boys who ran about

among the horses, trailing his lariat to throw over some pony which he

knew. By a fortunate jerk he curled it about one's neck, the shy creature

crouching under its embracing fold, knowing full well the awful strangle

which followed opposition. With ears forward, the animal watched the naked

youth, as he slowly approached him along the taut rope, saying softly;

"Eh-ah-h-h -- um-m-m-um-m-m -- eh-h-h-h-h." Tying the rope on the horse's

jaw, with a soft spring he fixed himself on its back, tucking his loin-cloth

under him. Now he moved to the outskirts of the thronging horses, crying

softly to them as he and his brother separated their father's stock from

that of the neighbor herds. He had done this before, but he had never been

responsible for the outcome.

The faint rose of the morning cut the trotting herd into dull shadowy

forms against the gray grass, and said as plain as any words could to White

Weasel: "I, the sun, will make the grass yellow as a new brass kettle from

the traders. I will make the hot air dance along the plains, and I will

chase every cloud out of the sky. See me come," said the sun to White Weasel.

"Come," thought the boy in reply, "I am a man." For all Indians talk

intimately with all things in nature; everything has life; everything has

to do with their own lives personally; and all nature can speak as well

as any Crow.

Zigzagging behind the herd, they left the smell of smoke, carrion, and

other nameless evils of men behind them, until the bark of wolf-dogs dulled,

and was lost to their ears.

Daylight found the two boys sitting quietly, as they sped along beside

the herd of many-colored ponies. To look at the white boy, with his vermilioned

skin, and long, braided hair, one would expect to hear the craunch and

grind of a procession of the war-cars of ancient Gaul coming over the nearest

hill. He would have been the true part of any such sight.

"Brother," spoke his companion, "we must never shut our eyes. The Cut-Arms

are everywhere; they come out of the sky, they come out of the ground to

take our horses. You must watch the birds floating in the air; they will

speak to you about the bad Indians, when you learn their talk; you must

watch the wolves and the buffalo, and, above all, the antelope. These any

one can understand. We must not let the ponies go near the broken land

or the trees. The ponies themselves are fools, yet, if you will watch them,

you will see them turn slowly away from an enemy, and often looking back,

pointing with their ears. It may be only a bear which they go away from;

for the ponies are fools they are afraid of everything. The grass has been

eaten off here by these buffalo, and the ponies wander. I will ride to

the high hill, while you, brother, bring the herd slowly. Watch me, brother;

I may give the sign of danger." Saying which, the older boy loped gracefully

on ahead.

All day the herd grazed, or stood drooping, as the sun made its slow

arc over the sky, while the boys sat on the ground in the shadows cast

by their mounts, their eyes ceaselessly wandering. Many were the mysteries

of horse-herding expounded by the one to the other. That the white Absaroke

was hungry, it was explained, made no difference. Absarokes were often

hungry out in the hills. The Dakotah were worse than the hunger, and to

lose the ponies meant hunger in their father's lodge. This shadow-day herding

was like good dreams; wait until the hail beat on the ponies' backs, and

made them run before it; wait until the warriors fought about the camp,

defending it; then it was hard work to hold them quietly. Even when the

snow blew all ways at the same time, the Cut-Throats might come. White

Weasel found a world of half-suspected things all coming to him at once,

and gradually a realizing sense stole over him that the ponies and the

eating and the land were very serious things, all put here for use and

trouble to the Absaroke.

As the days wore on, the birds and the wild animals talked to the boy,

and he understood. When they plainly hovered, or ran wildly, he helped

to gather up the ponies and start them toward the lodges. If the mounted

scouts came scurrying along the land, with the white dust in a long trail

behind them, he headed for the cottonwoods with the herd, galloping. At

times the number of the ponies in his charge changed, as his father won

or lost at the game of "hand"; but after the dried-meat moon his father

had brought home many new ponies from the camps of the Cut-Arms toward

the Morning.

His father had often spoken praise of him beside the lodge-fire, and

it made him feel good. He was beginning to be a man, and he was proud of

it; he would be a warrior some day, and he would see that nothing hurtful

happened to his father's horses.

It was now the month of the cold moon. (2)

The skies were leaden at times; the snow-laden winds swept down from the

mountains, and in the morning Weasel's skin was blue and bloodless under

his buffalo-robe when he started out for the hills, where the wind had

swept the snow off from the weeds and grass. Never mind, the sun of the

yellow grass had not cooked the ambition out of him, and he would fight

off the arrows of the cold.

His brother, being older, had at last succumbed to his thirst for glory.

He had gone with some other boys to try his fortune on other people's horses.

Weasel was left alone with the herd. His father often helped him to take

the ponies out to good grazing, and then left him. The Absaroke had been

sore pressed by the Indians out on the plains, and had retired to the Chew-cara-ash-Nitishic (3)

country, where the salt-weed grew. Here they could be pushed no farther.

Aided by the circling wall of mountain, their own courage, and their fat

horses, they could maintain themselves. Their scouts lay far out, and the

camp felt as much security as a wild people can ever feel.

One day, as usual, Weasel had taken his ponies far away to fresh feed,

that near the camps having been eaten off. The day was bright, but heavy,

dense clouds drifted around the surrounding mountain-tops, and later they

crawled slowly down their sides. Weasel noticed this as he sat shivering

in his buffalo-robe ; also he noticed far away other horse herds moving

slowly toward the Arsha-Nitishic, along whose waters lay the camp of his

people. He began to gather his ponies and rode circling about. They acted

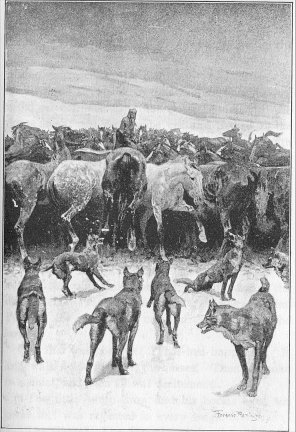

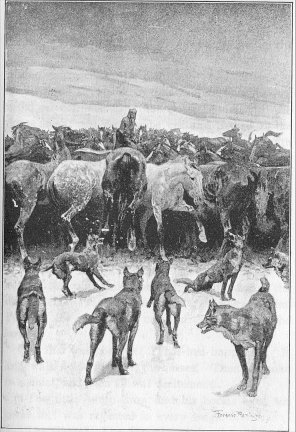

wildly -- strung out and began to run. Glancing about, Weasel saw many

big gray wolves loping along in unison with his charges.

It was not strange that wolves were in the vicinity of Indians. The

wolves, the ravens, and the Indians were brothers in blood, and all followed

the buffalo herds together. A lame or loose pony or a crippled Indian often

went the way of the wolves, and many wolves' hides passed over the trader's

counter. Thus they always got along together, with the raven last at the

feast.

As Weasel turned his nervous eye about him, he knew that he had never

seen so many wolves before. He had seen dozens and dozens, but not so many

as these. They were coming in nearer to the horses -- they were losing

their fear. The horses were running -- heads up, and blowing with loud

snorts. Weasel's pony needed no whip; his dorsal action was swift and terrific.

The wolves did not seem to pay particular attention to him they rather

minded the herd. They gathered in great numbers at the head of the drove.

Weasel could have veered off and out of the chase. He thought of this,

but his blue eyes opened bravely and he rode along. A young colt, having

lost its mother, ran out of the line of horses, uttering whinnies. Instantly

a dozen gray forms covered its body, which sank with a shriek, as Weasel

flashed by.

The leading ponies stopped suddenly and ran circling, turning their

tails to the wolves, kicking and squealing viciously. The following ones

closed up into the compact mass of horses, and Weasel rode, last of all,

into the midst of them. What had been a line of rushing horses two arrow-flights

long before, was now a closely packed mass of animals which could have

been covered by a lariat. In the middle of the bunch sat Weasel, with his

legs drawn up to avoid the crushing horses. It was all very strange; it

had happened so quickly that he could not comprehend. He had never been

told about this. Were they really wolves, or spirits sent by the Bad Gods

to destroy the boy and his horses?

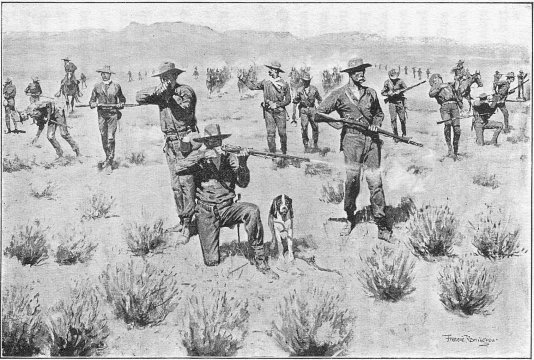

In the middle of the bunch sat Weasel

All his waking hours had been spent with the ponies ; he knew no other

world; he had scarcely had any other thoughts. He was with them now, but

instead of his protecting them they were protecting him. With their tails

turned toward the circling mass of devil-animals, they struck and lashed

when attacked. Nothing was heard but the snap of teeth, the stamp of hooves,

the shrill squealing of horses, with an occasional thud followed by a yelp.

The departing sun stole for a moment through a friendly rift in the clouds,

encrimsoning the cold snow, and then departed, leaving the gray tragedy

to the spirits of the night.

The smoke eddied from the top of the lodges; a bright spark showed from

time to time as some one lifted an entrance flap; the ponies huddled in

the dense bush ; the dogs came out and barked at the wilderness of never

ending plain. All was warmth and light, friendship, and safety, -- even

the baying wolf-dogs were only defying the shades and distances out beyond

for their own amusement; it was perfunctory.

"Why does not my son come in with the ponies? " asked the foster-father

of his squaw, but she could only answer, "Why?"

Wrapping his robe about him, he walked to the edge of the camp and stood

long squinting across the dusky land. He saw nothing to encourage him.

Possibly the ponies had come in, but why not the boy?

Oh! that was possible! That had happened! A long walk failed to locate

the horses. Then he spoke to a chief, and soon all was excitement.

"The little white Crow and his horses have not come in," was repeated

in every lodge.

"The Sioux! The Sioux!" spoke the echo.

It was too dark for a search. "The Sioux" was the answer to every question,

and no one hunted the Sioux by night. They might even now be on the outskirts.

Swiftly the scouts made their way to the outposts. The warriors loaded

their guns, and the women put out the fires. Every dog howled with all

the energy of his emotional nature. There was no sleep for the Absaroke

camp. It was seldom that an enemy got by the far-riding watchers of the

Crow camps, but there was always a fear. It had happened.

Ba-chua-hish-a sobbed and wailed all night in her lodge, while the foster-father

walked outside, speculating endlessly with his friends. Long before day

he was mounted, and with a small party far on the way to the herd-grounds

which he had chosen the day before.

As the plain began to unfold itself to their straining eyes, their quick

ears ran ahead of them. A snarling, a horse-squealing, a curious medley

of sounds, bore on them. Being old men, they knew. "It is the wolves,"

said they, almost in a chorus. Forward with a rush, a shrill yelling, and

firing, swept the little party. The sun strove mightily to get over the

mountains to help them. They now saw the solid mass of horses, with the

wolves scurrying away on all sides. A faint answering human whoop came

from the body of the beleaguered horse band. As the rescuers rode up, the

ponies spread out from each other. Relieved from the pressure of the slimy

fangs, the poor animals knew that men were better than wolves. Some of

them were torn and bloody about the flanks; a few lay still on the snow

with their tendons cut; but best of all which the Indians saw was little

White Weasel sitting in the midst of the group. He allowed his robe to

fall from his tight clutch. The men pushed their horses in among the disintegrating

bunch. They saw that the boy's lips were without color, that his arms hung

nerveless, but that his brave, deep eyes were open, and that they showed

no emotion. He had passed the time of fear, and he had passed the time

for hope, long hours ago.

They lifted him from his horse, and laid him on the ground, covered

with many robes, while willing hands kneaded his marbled flesh. A fire

was built beside him, and the old men marvelled and talked. It was the

time when the gray wolves changed their hunting-grounds. Many had seen

it before. When they sought the lower country, many grasses ago, to get

away from the snow, one had known them to eat a Crow who happened in their

way; this when he was a boy.

The wolves did not always act like this -- not every snow. Sudden bad

storms in the mountains had driven them out. The horse herds must be well

looked after for a time, until the flood of wolves had passed down the

valley.

The tired ponies stood about on the plain with their heads down. They,

too, had become exhausted by the all-night fight. The sun came back, warm

and clear, to see a more cheerful scene than it had left. Little Weasel

spoke weakly to his father: "The Great Spirit came to me in the night,

father, -- the cold wind whispered to me that White Weasel must always

carry a hoof of the white stallion in his medicine-bag. 'It is the thing

that will protect you,' said the wind. The white stallion lies over there

cut down behind. Kill him, and give me one of his rear hooves, father."

Accordingly, the noble beast, the leader of the horses in battle, was

relieved of what was, at best, useless suffering, -- sacrificed to the

gods of men, whom he dreaded less than the wolves, -- and his wolf-smashing

hoof did useful things for many years afterward.

hite Weasel's tough

body soon recovered from the freezing night's battle between the animals.

It had never been shielded from the elements, and was meat fed. The horses

ate grass, because their stomachs were so formed, but he and the wolves

ate meat. They had the canines. In justice to the wolves, it must be said

that all three animals represented in the fight suffered in common; for

if the boy had chilled veins, and the ponies torn flanks, many wolves were

stiffened out on the prairie with broken ribs, smashed joints or jaws,

to die of hunger. Nature brings no soup or warmth to the creature she finds

helpless.

hite Weasel's tough

body soon recovered from the freezing night's battle between the animals.

It had never been shielded from the elements, and was meat fed. The horses

ate grass, because their stomachs were so formed, but he and the wolves

ate meat. They had the canines. In justice to the wolves, it must be said

that all three animals represented in the fight suffered in common; for

if the boy had chilled veins, and the ponies torn flanks, many wolves were

stiffened out on the prairie with broken ribs, smashed joints or jaws,

to die of hunger. Nature brings no soup or warmth to the creature she finds

helpless.

The boy's spiritual nature had been exalted by the knowledge that the

Good God had not only held him in His saving arms during the long, cold,

snarling night, but He had guaranteed his continual protection and ultimate

salvation. That is no small thing to any person, but to the wild man, ever

in close communion with the passing of the flesh, to be on intimate terms

with the something more than human is a solace that dwellers in the quiescent

towns are deadened to. The boy was not taught physical fear, but he was

taught to stand in abject awe of things his people did not understand,

and, in consequence, he felt afraid in strange places and at inopportune

times.

One evening, as the family to which White Weasel belonged sat about

the blaze of the split sticks in their lodge, Fire-Bear, the medicine-man,

entered, and sat down to smoke his talk with the foster-father. Between

the long puffs he said: "Crooked-Bear wants us to bring the white Absaroke

to him. The hot winds have come down the valley, and the snow has gone,

so we can go to the mountains the next sun. Will you go with me and take

the boy? The Absaroke must do as the Crooked-Bear says, brother, or who

knows what may happen to us? The old man of the mountain is strong."

After blinking and smoking for a time the foster-father said: "The boy's

and Crooked-Bear's skins are of the same color; they are both Sparrowhawks

in their hearts. His heart may be heavy out there alone in the mountains

-- he may want us to leave the boy by his fire. Ba-cher-hish-a would mourn

if this were done. I fear to go, brother, but must if he ask it. We will

be ready when the morning comes."

When the dark teeth of the eastern mountains bit into the gray of approaching

day, the two old Indians and the boy were trotting along, one behind the

other. The ponies slithered in the pools and little rivulets left by the

melted snow, but again taking the slow, steady, mountainous, stiff-legged,

swinging lope across the dry plain, they ate the flat miles up, as only

those born on the desert know how to do.

The boy had often heard of the great Crow medicine-man up in the mountains

near where the tribe hovered. He seldom came to their lodges, but the Indians

frequently visited him. Weasel had never seen him, for the boys of the

camp were not permitted to go near the sacred places where the old man

was found. He had requested this of the chiefs, and the Absaroke children

drank the mystery and fear of him with their mothers' milk. He was one

of the tribal institutions, a matter of course; and while his body was

denied them, his advice controlled in the council-lodges. His were the

words from God.

Weasel was in the most tremendous frame of mind about this venture.

He was divided between apprehension and acute curiosity. He had left his

mother sobbing, and the drawn face of his father served only to tighten

his nerves. Why should the great man want to see White Weasel, who was

only a herd-boy? Was it because his hair and his eyes were not the color

of other boys'? He was conscious of this difference. He knew the traders

were often red and yellow like him, and not brown and black as the other

people were. He did not understand the thing, however. No one had ever

said he was any thing else than an Absaroke; he did not feel otherwise.

Approaching the mountains, the travellers found the snow again, and

climbed more slowly along the game-trails. They had blinded their path

by following up a brook which made its way down a coulee. No one left the

road to Crooked-Bear's den open to the prowling enemy. That was always

understood. Hours of slow winding took them high up on the mountains, the

snow growing deeper and less trodden by wild animals, until they were among

the pines. Making their way over fallen logs, around jagged boulders, and

through dense thickets, they suddenly dropped into a small wooded valley,

then up to the foot of the towering terraces of bare rock, checkered with

snow, where nothing came in winter, not even the bighorns.

Soon Weasel could smell fire, then dogs barked in the woods up in front.

Fire-Bear called loudly in deep, harsh Indian tones, and was answered by

a man. Going forward, they came first to the dogs, -- huge, bold creatures,

-- bigger and different than any Weasel had ever seen. Then he made out

the figure of a man, low in tone and softly massed against the snow, and

beside him a cabin made of logs set against the rock wall.

This was Crooked-Bear. Weasel's mind had ceased to act; only his blue

eyes opened in perfect circles, seemed awake in him, and they were fixed

on the man. The big dogs approached him without barking, -- a bad sign

with dogs. Weasel's mind did not concern itself with dogs. In response

to strange words from the white medicine-man they drew away. Weasel sat

on his pony while the older men dismounted and greeted Crooked-Bear. They

did not shake hands -- only "hat- wearers" did that. Why should an Indian

warrior lose the use of his right hand for even an instant? His hand was

only for his wife and children and his knife.

In response to the motion of his father's hand, the boy slid off his

pony. Taking him by the shoulder, the father drew him slowly toward Crooked-Bear

until they were directly in each other's presence. Weasel's eyes could

open no farther. His whole training was that of an Indian. He would not

have betrayed his feelings under any circumstances; he was also a boy,

and the occasion was to him so momentous that he was receiving impressions,

not giving them. A great and abiding picture was fast etching itself on

his brain; his spongelike child-mind drank up every drop of the weird situation.

He had seen a few white men in his life. He had not forgotten Virginia

City, though terror had robbed him of his powers of observation during

that ordeal. He had seen the traders at the post; he had seen the few white

or half-white men who lived with his people, but they were not like this

one.

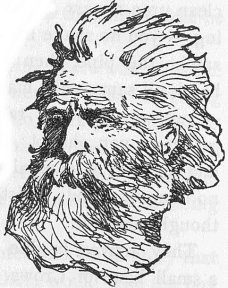

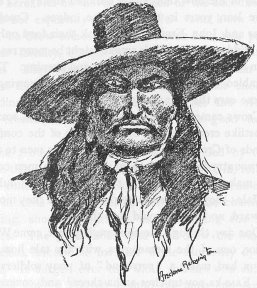

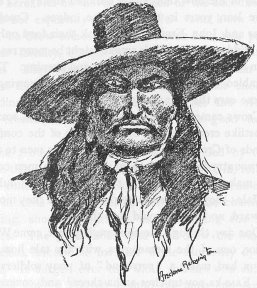

The old man of the mountain (4)

as crooked as his name implied. He also suggested a bear. He looked rude

even to the Indians. It seemed that Nature had laid her hands on his shoulder

and telescoped him together. He was humpbacked. His arms and legs were

as other men's are, though his shortened body made his hands fall to his

knees.

He was dressed in Indian buckskin, greased to a shine and bronzed by

smoke. He leaned on a long breech-loading rifle, and carried a huge knife

and revolver in his belt. His hat was made of wolfskin after the Indian

fashion, from underneath which fell long brown hair, carefully combed,

in profuse masses. Seen closely he was not old -- merely past middle life.

His strong features were weather-stained and care-hardened. They were sculptured

with many an insistent dig by Nature, the great artist; she had gouged

deep under the brows; she had been lavish in the treatment of the nose;

she had cut the tiger lines fearlessly, but she had covered the mouth and

lost the lower face in a bush of beard. More closely, the whole face was

open, the eyes mild, and all about it was reposeful -- sad resolution dominated

by a dome of brain. Weasel warmed under the gaze of the kind face -- the

eyes said nothing but good; they did more than that: they compelled him

to step forward toward the strange figure, who put his hand on Weasel's

shoulder and led him tenderly in the direction of the cabin door. Weasel

had lost his fear and regained the use of his mind.

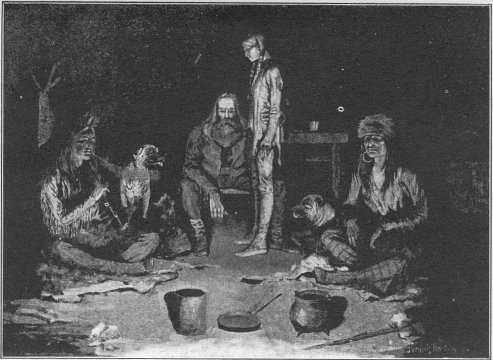

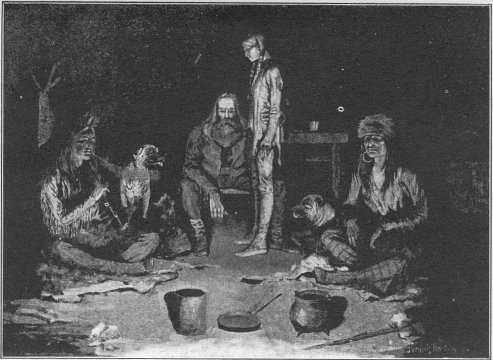

As the men stooped almost on hands and knees to enter the den of Crooked-Bear,

they were greeted by the acrid smell of smouldering ashes, and probably

by other odors native to their noses. Crooked-Bear stirred the ashes and

laid split wood on them. It was pine which spat and broke out in a bright

flame, painting the wild figures against the smoked logs and rock wall.

It illumined a buffalo-covered bunk, piles of parflèche full

of dried meat, a saddle and pack panniers, cooking pots and pans on the

hearth, all deeply sooted, a table and chair made with an axe, and in one

corner some shelves, equally rude, piled with brown and dirty books. Many

small knick-knacks intruded their useful presence as one looked with more

care, but the whole was the den of a man of some remote century. The sabre-toothed

tiger might snarl at the door but for the Sharp's rifle standing in the

corner; that alone made time and distance.

"Your ponies must starve to-night, brother," spoke Crooked-Bear. "Go

put them in my house where the horses live in summer-time. It is cold up

here in the mountains -- we have even no cottonwoods for them to eat. The

bear and the wolves will not spring on them, though the big cats are about."

All this said the white man in the language of the Absaroke, though it

may be said it sounded strange in Weasel's ear. When he spoke to the dogs,

the boy could not understand at all.

While the Indians looked after their ponies, the white man roasted meat

and boiled coffee. On their return, seeing him cooking, Fire-Bear said:

"Brother, you should have a squaw to do that. Why do you not take Be-Sha's

daughter? She has the blood of the yellow-eyes in her. She would make your

fire burn."

"Tut, tut," he replied, "no woman would make my fire burn. My fire has

gone out." With a low laugh, Crooked-Bear added, "No woman would stay long

up here, brothers; she would soon run away." Fire-Bear said nothing, for

he did not understand. He himself would follow and beat the woman and make

her come back, but he did not say so.

Having eaten, and passed the pipe, Fire-Bear asked the hermit how the

winter was passing -- how the dry meat was lasting -- what fortune had

he in hunting, and had any enemies beset him? He was assured his good friends,

the Absaroke, had brought him enough dry meat, after the last fall hunt,

to last him until he should no longer need it. The elk were below him,

but plentiful, and his big dogs were able to haul enough up the hills on

his sleds. He only feared for his tobacco, coffee, and ammunition; that

had always to be husbanded, being difficult to get and far to carry. Further,

he asked his friend, the Indian, to take some rawhides back to the women,

to be dressed and made into clothes for his use.

"Has my brother any more talking papers from the yellow-eyes? Do the

white men mean to take the Sioux lands away from them? The Sioux asked

the Absaroke last fall to help drive the white men out of the country,

saying, 'If they take our lands to dig their badger-holes in, they will

soon want yours.' The Absaroke would not help the Cut-Throats (5);

for they are dogs they wag their tails before they bite," spoke Fire-Bear.

"Yes, brother," replied Crooked-Bear; "if you should, by aiding the

Sioux, get rid of the white men, and even this you would not be able to

do, you would still have the Sioux, who are dogs, always ready to bite

you. No, brother, have nothing to do with them, as I have counselled you.

The Sak-a-war-te said this to me: 'Before the grass on the plains shoots,

send a strong, fat-horse war-party to the enemy and strike hard. Sweep

their ponies away -- they will be full of sticks and bark, not able to

carry their warriors that moon; tear their lodges down and put their fires

out; make their warriors sit shivering in the plum bushes. That is the

way for the Crows to have peace.' The Great Spirit has said to me: 'Tell

the Absaroke that they can never run the buffalo on the plains in peace,

until the Chis-chis-chash, the Dakotahs, and the Piegan dare not look them

in the face. That, and that only, is the path.'"

Far into the night the men talked of the tribal policy -- it was diminutive

statesmanship, commercial politics with buffalo meat for money. As Crooked-Bear

sat on his hewn chair, he called the boy to him, put his arm around him,

and stood him against his knee. The youth's head rose above the rugged

face of the master of Indian mystery; he was in his first youth, his slender

bones had lengthened suddenly in the last few years, and the muscles had

tried hard to catch up with them. They had no time to do more than that,

consequently Weasel was more beautiful than he would ever be again. The

long lines of grace showed under the tight buckskins, and his face surveyed

the old man with boyish wonder. Who can know what the elder thought of

him in return? Doubtless he dreamed of the infinite possibilities of so

fine a youth. He whose fire had gone out mused pleasantly as he long regarded

the form in whom they were newly lighted.

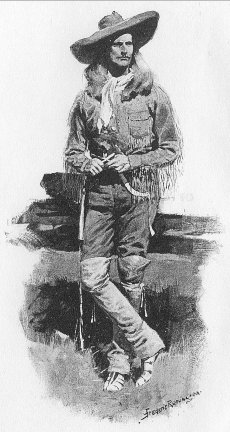

He called the boy to him and put his arm around him.

Slowly he began to speak, using the Indian forms of speech, and supplementing

them with the gestures which only Indians can command. "Brother, we have

lived a long time. We have made the medicine strong for the Absaroke. We

have taken the words of the Good Gods to the council-lodge when the tribe

ran wildly and knew not which way to turn. We will follow soon the others

who have gone to the Shadowland. The Absaroke will be left behind, and

they must have wise men to guide them when we are gone. This young man

will be one of those -- I have seen that in my dreams. He must stay here

with me in the lonely mountains, and I will teach him the great mystery

of the white men, together with that of the people of his own tribe. He

will visit his father's lodge whenever his heart is hungry. He owes it

to himself and to his people to grow strong in the mystery, and then some

day the tribe will lean on him. Shall he stay, brothers?"

White Weasel, with arms dropped to his side, made no move. The flame

from the hearth lighted one of his starlike eyes as it stood open, regardful

of the strange old man. The Indians passed the pipe, and for a long time

there was no sound save the snapping of the fire and the pines outside

popping with the cold.

At last Fire-Bear spoke: "We have had our ears open, brother. Your talk

is good. The Sak-a-war-te demands this. The boy shall stay."

Weasel's foster-father held his peace. His was the sacrifice, but the

Great Spirit could not ask too much of him. In reply to another inquiry,

he said that the boy should stay; then wrapping himself in his robe, he

lay down before the fire to hide his weakness.

"Will you stay with me?" asked the Wonder- Worker of the boy, stroking

his yellow hair and pouring the benevolence of his fire-lighted face in

a steady stream on the youth.

"You have no ponies to herd, father. What shall I do?" he asked.

"I have no ponies for you to herd, but I have many mysteries here,"

tapping the boy's forehead with his finger, "for you to gather up and feed

on, and they are greater than ponies."

" I will stay, father."

That the sun rose with customary precision made little difference to the

sleepers in the mountain den. Little of its light crept down the hole against

the rock wall, and none of it penetrated the warm buffalo-robes. The dogs,

growing uneasy, walked about and scratched at the door; they had not been

disturbed by last night's vigil. Waking, one by one, the men threw off

the robes and went out; all but the boy, who lay quite still, his vitality

engaged in feeding the growing bones and stretching muscles.

Out by the stable Crooked-Bear said: "Take your ponies and that of the

boy and ride away. They will starve here, and you must go before they weaken

and are unable to carry you. A boy changes his mind very quickly, and he

may not think in the sunlight what he did in the firelight. I will be kind

to him. Tell Ba-cher-hish-a that her son will be a great chief in a few

grasses."

Silently, as only the cats and the wolves and the Indians conduct themselves,

the men with the led horses lost themselves among the trees, leaving Crooked-Bear

standing by his abode with the two great cross-bred mastiffs, on their

hind legs, leaning on him and trying to lick his face. As they stood together,

the dogs were taller than he, and all three of them about the same color.

It was a fantastic scene; a few goblins, hoarse mystery birds, Indian devils,

and what not beside, might have been added to the group and without adding

to its strangeness. Weasel had foukd a most unearthly home; but as he awoke

and lay looking about the cabin, it did not seem so awfully strange. Down

through the ages borne through hundreds of wombs in some mysterious alcove

of the boy's brain had survived something which did not make the long haired

white man working about the fire, the massive dogs, the skins of wild animals,

the sooty interior, look so strange.

As Weasel rose to a sitting posture on the bunk, the dogs got up also.

"Down with you! Down with you, Eric! and you, Hope! You must not bother

the boy," came the hermit's words of command. The dogs understood, and

lay heavily down, but their eyes shone through heavy red settings as they

regarded the boy with unarrested attention.

"I am afraid of your dogs, father; they are as big as ponies. Will they

eat me?"

"No; do not be afraid. Before the sun goes over the mountains they will

eat anyone who would raise his hand against you. Come, put your hand on

their heads. The Indians do not do this; but these are white dogs, and

they will not bite any one who can put his hand on their heads," spoke

Crooked-Bear in his labored way with the Indian tongue. He had never mastered

all the clicks and clucks of it.

The meat being done, it was put on the table, and White Weasel was persuaded

to undertake his first development. The hermit knew that the mind never

waits on a starved belly, so he explained to the boy that only dogs ate

on the ground. That was not obvious to the youngster; but he sat in the

chair and mauled his piece of meat, which was in a tin plate. He drank

his coffee out of a tin cup, which he could see was full better than a

hollow buffalo horn, besides having the extra blandishment of sugar in

it. As the hermit, occupying an up-turned pack-saddle opposite, regarded

the boy, he could see that Weasel had a full forehead that it was not pinched

-- like an Indian's; he understood the deep, wide-open eyes which were

the color of new ice, and the straight, solemn nose appealed to him also.

The face was formal even to the statuesque, which is an easy way of saying

he was good-looking. The bearer of these messages from his ancestors to

Crooked-Bear quite satisfied him. He knew that the baby Weasel had been

forcibly made to enter a life from which he himself had in mature years

voluntarily fled, and for which neither was intended. They had entered

from opposite doors only, and he did not wish to go out again, but the

boy might. He determined to show him the way to undo the latching.

After breakfast began the slow second lesson of the white man's mystery.

It was in the shape of some squaw's work, and again the boy thought unutterable

protests. Crooked-Bear had killed an elk the day before, some considerable

distance down the mountain, and taking his dogs with the sledges, they

sallied down to get it. What with helping to push the heavy loads in aid

of the dogs and his disgust of being on foot, at their noon home-coming

White Weasel's interest began to flag.

Crooked-Bear noticed this, and put even more sugar into the boy's coffee.

He had a way of voicing half-uttered thoughts to himself, using his native

tongue, also repeating these thoughts as though to reenforce them. " I

must go slow -- I must go slow, or the boy will balk. I must lead him with

a silken thread; the rawhide will not do -- it will not do." Meanwhile

the growing youth passed naturally into oblivion on the bunk.

"These Indians are an indolent people," the prophet continued. "They

work only by fits and starts, but so am I indolent too. It befits our savage

way of life," saying which, he put some coffee-berries into a sack and

began pounding them with an axe. "I do not know -- I do not remember to

have been lazy; it does not matter now if I am. No one cares, and certainly

I do not. I have tramped these mountains in all weathers; I have undergone

all manner of hardships, yet they said I could not be a soldier in the

armies down south. Of course not -- of course not; a humpback could not

be a soldier. He is fit only to swear at. Men would laugh at a crooked-

back soldier. She could see nothing but my back. Ah -- ah -- it

is past now. Men and women are not here to see my back; the trees and the

clouds, the mountains and my dogs, do not look at my spine. The Indians

say my back was bent by my heavy thoughts. The boy there has a straight

back, and I hope he may walk among men. I will see that he does; I will

give him the happiness which was denied me, and it pleases me to think

that I can do this. I will create a happiness which the vicissitudes of

this strange life seem to have denied him, saying, 'Weasel, you are to

be a starved and naked nomad of the plains.' No! no! boy; you are not to

be a starved and naked nomad of the plains. I have in my life done no intentional

evil, and also I have done no intentional good; now this problem of the

boy has come to me how it reaches out its roots for the nourishing things

and how its branches spread for the storms!"

Having accompanied these thoughts by the beating of the axe, the hermit

arose, and stood gazing on the sleeping lad. "Oh, if I had only had your

back! -- oh! oh! oh! But if only you had had my opportunities and education

--well, I am not a god; I am only a man; I will do what a man can."

When the boy awoke, the hermit said, " My son, did you ever make a gun

speak?"

"No; my father's gun hangs with his mystery-bag on his reclining-mat,

and a woman or child dare not lay their fingers on it."

"Would you like to make a gun talk?" came gently, but Weasel could only

murmur. The new and great things of life were coming fast to him. He would

almost have given his life to shoot a gun; to own one was like the creation,

and the few similar thoughts of men; it was beyond the stars.

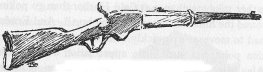

" Weasel," said the man, taking up a carbine, and calling him by name,

which is un-Indian, "here is a gun; it loads in the middle; I give it to

you; it is yours." With which he handed the weapon to the boy.

After some hesitation Weasel took the gun, holding it stiffly in front

of him, as an altar-boy might a sacred thing. He could say nothing, and

soon sat down, still holding the firearm, regarding it for a long time.

When he could finally believe he was not dreaming, when he comprehended

that he really did own a gun, he passed into an unutterable peace, akin

to nothing but a mother and her new-born child. His white father stepped

majestically from the earth that Weasel knew into the rolling clouds of

the unthought places.

"To-morrow I will take my gun, and you will take your gun, and we will

walk the hills together. Whatever we see, be it man or beast, your gun

may speak first," proposed the prophet.

"Yes, father, we will go out with the coming of the sun. My heart is

as big as the mountains; only yesterday I was a herd-boy, now I own a gun.

This brought it all to me," the boy said almost to himself, as he fumbled

a small bag hanging at his neck. The bag contained the dried horse's hoof.

Throwing back his long hair, the prophet fixed his face on his new intellectual

garden. He saw the weeds, and he hardly dared to pull them, fearing to

disturb the tender seeds which he had so lately planted. Carefully he plucked

at them. "No, my son, that was not your medicine which brought the gun,

but my medicine; the medicine of the white man brought it to you. The medicine

of the white man brought the gun to you because the Great Spirit knew you

were a white boy. The medicine of the white man is not carried in a buckskin

bag; it is carried here." And the prophet laid his finger on his own rather

imposing brow; he swept his hair away from it with a graceful gesture,