Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote Barsoom for Barsoomians.

That is to say, except for the occasional interloper from Earth the stories

of Mars were by and for Martians. Sure, there was the occasional

interloper from Earth, John Carter or Ulysses Paxton, but these guys tended

to go native pretty quickly, adopting the methods and mores of the culture

around them. But for the most part, the Barsoom stories took

Barsoom on its own terms, looking at life and existence as the natives

saw it. It truly was another world, very distinct from our own.

Earthlings became a part of it, but their earthly natures were not terribly

significant.

There's no story, for instance, where John Carter sets

up a modern "Henry Ford" style industrial plant to mass produce fliers,

for example, or where he single-handedly builds an industrial structure

to get himself a working radio... Although there are other examples

of such stories throughout science fiction, beginning with Mark Twain's

Connecticut

Yankee in King Arthur's Court. That's just a different

kind of story.

There are, of course, lots of different kinds of stories

in science fiction and literature. Spaceman's Burdenwas

another one.

Look at it this way. First come the explorers

and adventurers, people who go out and discover new worlds, new realms.

John Carter on Barsoom, Professor Challenger in the Lost World, Sinbad

of the Seven Seas, Stanley and Livingston in Africa, Lewis and Clarke in

America, Columbus and Magellan, the intrepids who ventured into India and

China. The adventurers brought back tales and stories, exotic trinkets,

the philosophies and techniques of new lands.

But on Earth, the adventurers and explorers of the European

era were eventually followed by traders and armies, the companies came...

The British East India Company, the North West Company, the Hudson's Bay

Company, the Congo Rubber Company, and with the companies, came white men,

European cultures and values, commerce, fortresses, trade, armies and Empires.

And as it went in the real world, so it went in science

fiction, particularly the unconscious science fiction of the thirties and

forties, even into the fifties and sixties. It was the science

fiction that said that men of Earth would reach out to other worlds, savage

worlds, wild worlds, or civilized but less advanced worlds, and would rule

them. Because, after all, what else was there to do with them?

And wasn't it the best thing, for them and us? Although, on

second thought, perhaps it wasn't such a good thing at all, some might

aver.

But it was basically all a version of the belief in "White

Man's Burden," written in an era when Europe and America ruled, directly

or indirectly, the whole of the rest of the world. It was a

time when you could look at a map of Africa and sea practically every bit

of it dotted with the colours of Europe. A time when India

was British, Indochina French, Indonesia Dutch and China a prostrate giant

where local citizens stepped into the gutters to let European and Americans

filled with purpose stride by. White Man's Burden dies hard,

it's become the last reason for America to try to hold onto Iraq...

the ‘moral obligation’ to protect the Iraqis from each other.

So it's no surprise that the science fiction of the day

should reflect the world it lived in, and White Man's Burden should have

its literary equivalent in Space Man's Burden. If anything,

it was kind of late. The ‘space man's burden’ stories really

only began to show up in the thirties and forties, whereas the colonial

empires had been building since the 17th century and probably had peaked

out at the turn of the 20th. I don't hold it against the literature

for being late to the party. Science fiction as a mass commercial

form really only dated back to the 20's at best. So they were pretty

on top.

Sometimes

it was fairly unconscious stuff. H. Beam Piper's

Uller

Uprising features a local race of aliens trying to throw off the

rule of human empire, and self-righteously getting a nuke down the throat

for daring to threaten white men and women. Other later works,

including Poul Anderson's Palesotechnic league stories had a much

more conflicted view of the morality of empire.

Sometimes

it was fairly unconscious stuff. H. Beam Piper's

Uller

Uprising features a local race of aliens trying to throw off the

rule of human empire, and self-righteously getting a nuke down the throat

for daring to threaten white men and women. Other later works,

including Poul Anderson's Palesotechnic league stories had a much

more conflicted view of the morality of empire.

Interestingly, Burroughs never really wrote this kind

of story. For all that it may be fashionable to diss the man

for racism, its worth noting that his protagonists joined and triumphed

within the societies they encountered. They didn't overrun it.

Tarzan was always 'of' the Apes. Imperial aspirations or pretensions

were absent from Burroughs work, there was no divine or racial right to

European or American rule, no 'White Man's' or 'Space Man's' burden.

Possibly Burroughs writing formed before this genre really

caught on. Remember that he started off with many of his key

series, Barsoom, Tarzan, Pellucidar and Caspak, begun and often several

books written between 1912 and 1920. But almost certainly, Burroughs

would have been well familiar with hoary old imperialists like the author

of Mowgoli, Rudyard Kipling, and his period of productive writing extended

through the 1930s and 40s. So there was ample opportunity for him

to get into it. But he didn't.

I suppose that for whatever reason, Burroughs just wasn't

interested. Empire invariably is like the Holiday Inn.

No matter what far flung exotic realms it penetrates, the Imperial aesthetic

is simply to reproduce a version of home far, far away. Just

as Holiday Inn hotel rooms are pretty much the same from Nepal to Tierra

Del Fueggo, Imperial life in Kinshasha and New Delhi are pretty much the

same... Only the colour of the waiters differ. For better

or worse, that just didn't seem to do it for Burroughs, the notion of imposing

middle America on the Jungles of Africa or the deserts of Barsoom was fundamentally

repellent. Barsoom was for Martians, and if an Earthman went

there, well, he could darned well don a harness, pick up a sword and try

and fit in.

It's just me, but I think that this says something about

Burroughs' racism or lack thereof. Let's face it.

Tarzan and John Carter were white supermen in lands of black Africans or

red Martians. But the simple fact that they were white supermen didn't

translate to the notion that all white men were supermen, or particularly

super, or that white society had any innate superiority.

Of course, now that I think of it, David Innes with his

Empire of Pellucidar is a bit of an exception isn't it... Well,

perhaps an exception that proves the rule. Abner Perry was

nobody's idea of the Aryan superman, and his notion of bringing the benefits

of civilization to Pellucidar through the re-invention of poison gas suggests

that someone's tongue was firmly in their cheek.

Besides, if David Innes was playing at White Man's Burden

in Pellucidar, Carson Napier on Venus was discovering that the folk of

the jungle world considered him something of a rube. And in

Pellucidar, as with Barsoom, Burroughs was more than happy to hand the

reins of the protagonist over to local heroes, like Gahan of Gathol, Tan

Hadron of Hastor, or Tanar of Pellucidar.

But where was I?

Oh yes. Burroughs never brought Space Man's

Burden to Barsoom.... His Mars would always belong to Dejah

Thoris and Tars Tarkas and their cities and tribes....

Which brings us to Leigh Brackett....

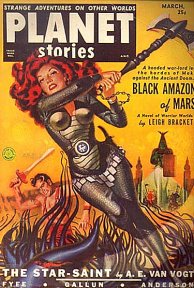

Leigh Brackett

and the Universal Mars

Leigh Brackett, born 1915, died 1978, was one of the more

talented and influential writers in the field of science fiction.

In addition to the genre, she wrote mystery novels, and was even a notable

screenwriter -- among her scripts are The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo,

The

Long Good-bye and remarkably, The Empire Strikes Back.

Her body of SF work consisted of some sixty short stories and a dozen novels

between 1940 and 1978, including collaborations with Ray Bradbury and with

her husband, Edmund Hamilton.

And Bracket wrote Mars. Her first story published,

in 1940, was Martian Quest. She would follow that up

with ten stories and four novels set principally on her Mars, and another

half dozen set on or around other planets of the solar system which touched

on Mars, as well as over a dozen more set on Venus, Mercury, the Jovian

moons or other regions, all of which constituted a kind of interlocking

solar system.

Leigh Brackett and Edmund Hamilton

Indeed, you can look up Leigh Brackett's Solar System

on the Wikipedia, as well as separate entries for her Mars, Venus, Mercury

and Jupiter.

Leigh

Brackett's Solar System

Mars

in the Fiction of Leigh Brackett

Venus

in the Fiction of Leigh Brackett

Mercury

in the Fiction of Leigh Brackett

Jupiter

in the Fiction of Leigh Brackett

Did Brackett set out to write a coherent solar system,

did she sit down and design herself a universe? Probably not.

As the Wikipedia says, it reflected an ‘accumulating use of detail and

setting from one story to the next, until a reasonably coherent universe

had been built up after the fact.’

It's sort of a natural thing that writers do, borrowing

from oneself. You put all that work into coming up with a scene

or setting, it offers multiple possibilities, you find yourself referencing

or re-using it. Stories or ideas inspire each other, and a

writer often tips the hat to other stories or characters.

You get any writer who accumulates a body of work, and

quite often, you'll start to see internal references between one story

or novel and another, that applies to everyone from Shakespeare to Faulkner,

from Burroughs to Lovecraft to King. I don't know why, maybe

it's a natural in-joke for writers to slip characters or settings from

other stories, perhaps there's an element of laziness, or a kind of economy

of creativity at work. But just about any writer with a real body

of work winds up doing it to some extent. Building worlds in your

head seems to bring an urge to connect them up, and a literary universe

of sorts comes into being.

Of course, it doesn't just stop there. Writers are

influenced by other writers, they're influenced by predecessors and friends.

They're definitely influenced by the culture around them, by the stories,

the narratives, the movies and films, the politics and politicians of the

day. A lot of this winds up in their writing, sometimes in

subtle ways, sometimes in obvious ways, and sometimes in little tip of

the hat 'in jokes' or references, sort of like cameos in the movies.

For instance, without looking too hard, you can find a

few Lovecraft references here and there in the works of Steven King.

Deliberate and direct references. Does Lovecraft's Chtulhu

mythos include the oeuvre of King? Well, possibly, if you're

willing to go there. Or perhaps just a few of King's stories

fit in Lovecraft's world, and most in his own world, and a few more inhabit

a strange borderland.

But anyway, Leigh Brackett's stories featured a Mars whose

landscape she found herself re-using. Not just the larger vision

of a Mars, but specific things -- cities like Valkis and Jekkara are mentioned

again and again, Madame Kan's house of pleasure comes about, the lost city

of Sinharat is revisited, Rhiannon is a part of ancient Mars.

And it expands, Eric John Stark is reused for a second Martian story, and

then goes to Venus, meanwhile, the setting of his first story is recycled

for another story. The Venus stories accumulate as well, and

the milieu extends to Mercury and Jupiter.

In some ways, its not a terribly coherent universe.

As the Wikipedia article notes, good frikking luck trying to establish

a timeline. There's gaps and problems, as there usually is when you're

basically making it up as you go along.

But Brackett's Mars and Venus did not spring whole from

her imagination. As I've noted in other essays, both Mars and Venus

were already well established landscapes with their roots deep in the science

of the late 19th and early 20th century, and even more deeply rooted in

the social myths and narratives of the age. I don't propose

to go over it in detail, that would be tedious. If you're interested,

feel free to take a look at my other articles about Mars and Venus.

The short version is that between 1860 and 1940, there

was a powerful imaginary or cultural ‘landscape’ of Mars as an ancient,

dying, desert world. A place that had once had oceans and continents,

but which had gradually turned into a desert. In the narrative,

the Martians, if they existed, were an equally ancient and decadent race,

extending their civilization's life by building elaborate networks of canals.

This had developed through the work of astronomers like Schiaparelli, Flammarion

and Lowell, it had emerged through social philosophers, speculation, and

indeed, through the works of writers like H.G. Wells and Edgar

Rice Burroughs.

During this time, a second narrative emerged of Venus

as a young hot world, filled with oceans and teaming jungles, any civilization

on it would be new and raw, all but primitive. In between the

two, of course, was Earth, always the happy middle between too hot and

too cold, too young and too old, between oceans and jungles on the one

side and deserts and ruins on the other, between the ancient decadence

and decay of Mars and the squalling primeval riot of Venus.

Mars and Venus were not just planets for which a limited

set of astronomical observations existed, but they were psychic landscapes

in the culture, freighted with ideas and narratives that were embedded

in the culture. They were landscapes that were as real and

vivid, or as unreal and archetypal as the wild West, the mysterious Orient

and darkest Africa. Brackett did not invent her Mars or Venus,

for the most part, she inherited it.

It makes a bit of sense when you think about it.

It takes a heck of a lot of work to create a brand new world, and having

done so, the odds are it will be so strange and foreign that no one will

get into it. It's always much easier, and much more tempting,

for a writer to slip into a known world, a known milieu, a place that the

audience is already familiar and with and willing to go. The truth

is that often, people don't like things to be too strange. They like

familiar places where they know the ground rules.

And Brackett didn't simply inherit a generic Mars of bare

bones narratives, something that takes off from the writings or speculations

of a Percival Lowell. This would only give us an ancient race,

perhaps in decline, huddling around or along a few canals.

There was more to it: She was influenced,

guided, by the literary Mars. And let's face it, there were

more than a few variations on literary Mars, including Wells. But

the one that stood out, the one that she drew most heavily on, was Barsoom.

Consider the following parallels between Barsoom and

Brackett's Mars.

Both feature dominant races of Human Martians, all but indistinguishable

from Earth humans, physically, emotionally and sexually. Brackett's

Martians tend towards amber or yellow eyes, often have olive or weatherworn

skin colours, but they could walk the streets of Helium or New York without

attracting too much notice.

It's also society that revolves around personal honour and

shame, and known and notable for swordsmanship and personal weaponry.

It's also an equestrian society. Nope, they don't

have horses. But to get around, the Martians ride around on large,

bad tempered, somewhat reptilian beasts. By and large, Brackett

never really describes them, I don't think she even awards them a name.

They're simply ‘mounts’ ‘beasts’ ‘steeds’ etc.

In some of the stories, particularly Beast Jewel of Mars,

the elite city state Martians seem to have their own fliers, perhaps from

the Earthmen, or perhaps indigenous. The warriors walk around

in kilts and harnesses.

It's a Mars with lost races and hidden enclaves, especially

around the north pole, relics from bygone ages.

City

states, Martian Princesses, sword wielding, honour-driven, half-naked heroes

riding around on ungainly beasts, discovering lost enclaves....

Come on, this is Barsoom. This ain’t nothing but Barsoom.

Bits and pieces of this, tropes from here and there can be found in other

Mars novels. Otis Adelbert Kline's Mars books are like this

of course, but those draw directly from Barsoom. Arnold's Gullivar

Jones has a lot of this, as does Pope's Journey to Mars.

Both have been argued as candidates for Burroughs inspiration.

There are other stories and novels about human identical Martians, even

human identical Martians inhabiting city states. There were other

major Mars writers, like Wells and Bradbury, or C.S. Lewis.

City

states, Martian Princesses, sword wielding, honour-driven, half-naked heroes

riding around on ungainly beasts, discovering lost enclaves....

Come on, this is Barsoom. This ain’t nothing but Barsoom.

Bits and pieces of this, tropes from here and there can be found in other

Mars novels. Otis Adelbert Kline's Mars books are like this

of course, but those draw directly from Barsoom. Arnold's Gullivar

Jones has a lot of this, as does Pope's Journey to Mars.

Both have been argued as candidates for Burroughs inspiration.

There are other stories and novels about human identical Martians, even

human identical Martians inhabiting city states. There were other

major Mars writers, like Wells and Bradbury, or C.S. Lewis.

But the sheer volume of parallels is inescapable.

It seems mischievous to argue that Brackett could have come up with all

of these things independently, or that she might have drawn from other

writers or ‘common’ ideas. The truth is that Barsoom was just

the biggest and most obvious thing on the Martian landscape.

Brackett's first few stories were of Mars, and to a lesser

extent, Venus, and then the other planets of the solar system.

She began publishing in 1940. We can presume that she was reading

intensively in the genre before that. The entire Barsoom canon

up to Swords of Mars was published by 1936, and would have been

available to her. The romance themes implicit were probably

attractive and appealing to a young girl. In 1940, when her

first two or three published stories were about Mars, Burroughs was publishing

Synthetic

Men of Mars. Between 1940 and 1943, when Brackett published

eight Martian stories, five venus stories and six other solar system stories,

Burroughs was publishing through magazines on the same newsstands the novellas

that would be collected as Llana of Gathol,

Escape on Venus

and Savage Pellucidar.

Brackett's Mars was literally shoulder to shoulder with

Burroughs' Mars, appearing literally in the same magazines or on the same

newsstands, perhaps at the same times or within weeks or months of each

other. We have a young writer doing stories in the face of this large

cultural narrative, and in the face of this huge body of work.

I think that there's no question that Brackett's Mars was based largely

upon Barsoom. That's just the fact of the matter.

Brackett herself freely admitted the inspiration, as did

her husband Edmund Hamilton, in a forward to one of her short story collections.

Barsoom shaped Brackett's Mars.

Leigh Brackett's

Barsoom (Yeah, my subtitles suck. Live

with it.)

Barsoom may have been the starting point for Brackett's

Mars, but she really didn't write typically Barsoomian adventures.

Perhaps there was simply no point. Burroughs Martian adventures

were in a class by themselves, there was no point in trying to write in

that vein, at least, not on Mars. There's clones and then there's

clones.

Even Lin Carter, wanting to do Barsoom style adventures,

didn't have the nerve to set them on Mars. The comparison would be

inescapable, and so he relocated to Thanator. A lot of 'Burroughsian'

adventures tended to be set on other worlds, just as many Jungle Man adventures

tended to be set away from Africa.

Instead of ripping adventures, or sword and planet, or

planetary romance, as the genres are called Brackett opted for more personal

and more conflicted stories. The characters were rougher, more

ambiguous and often a lot more talkative. Instead of simple

plainspoken heroes, she shifted to hapless innocents and cynical thugs.

Her renditions of Mars were in their own ways, more complex but more primitive,

it was a world of mysteries and age, but one which did not suffer the brash

interlopers from Earth very well. Brackett's stories, on the

whole, are less about adventure than about fatal and futile culture clashes.

You won't see Burroughsian heroes in Brackett's Mars,

or if you do, the idea of them gets chewed up pretty quick. Eric John Stark

comes closest, but in many ways, he's an amoral anti-hero, chewed up, spat

out and as likely as not to be working for the wrong side or doing the

wrong things. He's a lot closer to Clint East wood's 'Man with no name'

than he is to John Carter, and a lot closer to being an occasionally principled

thug than either of those.

Indeed, that's basically his role in the Secret of Sinharat.

He's a renegade on the run, persuaded to infiltrate a gang of thugs, which

he can do, largely because he is a thug himself. There's a

gritty spaghetti western quality to Stark that's a marked contrast to the

wholesomely sociopathic John Carter.

Rick Urquhart of The Nemesis From Terra is another

testosterone-choked thug, a powerful force, but ultimately a barbarian.

In his first chapter, he shoots a little old lady who has given him shelter.

Rick's nemesis are Jaffa Storm and Ed Fallon, colonial exploiters. You

have the impression that Rick would have been happy enough working right

alongside them, had circumstances been different, and that his real objection

to them is that he's not running things. Rick's nominal allies recognize

a potential thug and tyrant and are at best ambivalent. In the end, Rick

realizes that the best thing he can do for Mars, once he's disposed of

other would-be tyrants, is to leave it.

Burk Winters of The Beast Jewel of Mars comes close

to being a John Carterish hero. He's a man so in love with his girl, Jill

Leland, that he risks everything... But in this case, risking everything

does not involve lots of heroic derring do, but rather volunteering himself

to the seamy underworld of Mars and addiction to an exotic drug, which

causes both mental and physical regression. There is, as with Burroughs,

an exotic and beautiful alien princess, Fand (option: evil). But Burk's

single act of courage and daring is to kidnap the Princess and expose her

to the same drug that is regressing him and his fellow Earthlings. What

does the Princess become?

"In spite of himself, he cried

out.... It had eyes, that was the worst of it. It had eyes, and it looked

at him."

So, he kidnaps a Princess and mutates her into a hideous

degenerate slug thing. Yikes. I don't think John Carter

ever imagined being that vile. In the end, Winters is regressed

to a bestial ape man who beats a swordsman to death with his bare hands...

And oddly you get the sense, he hasn't degenerated very far.

Only

Matt Carse from Sword of Rhiannon escapes being a violent thug,

largely because he's transported into the remote past where that sort of

thing is much more ok.

Only

Matt Carse from Sword of Rhiannon escapes being a violent thug,

largely because he's transported into the remote past where that sort of

thing is much more ok.

Heroes are mostly ineffectual. Or perhaps

ineffectual is the wrong word. Rather, all too often, their heroism,

their struggles seem irrelevant to the real personal or moral issues.

Burk Winters in the Beast Jewel shatters the drug trade, brings

down the royal house of Valkis and escapes with his girl. A typical

Burroughsian resolution? On the other hand, it's clear that

he could not save his girlfriend Jill from her drug addiction, and probably

can't save her or himself from its effects. At the core of Winters' adventure

is a deeper sense of futility and helplessness.

Similarly, Stark witnesses the defeat of evil Rama in

Secret

of Sinharat, but can't quite destroy their technology, instead, the

temptation to evil remains. The heroes of Mars Minus Bisha,

the Last Days of Shondakor, and Purple Priestess of the Mad Moon

all stumble into situations they cannot change. Their efforts, when

they make them, prove futile. They're either irrelevant, or they

make the situation worse. They come away with souls blighted by tragedy.

Carey, the hero of Return to Sinharat goes on an

epic quest to prove that the situation cannot be changed... and in fact,

shouldn't be changed. Matt Carse of Sword of Rhiannon turns out

to be a pawn of greater forces, the 'god' Rhiannon seeking revenge on lapsed

followers.

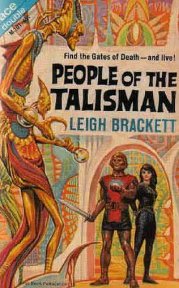

Even Eric John Stark in the People of the Talisman

(Black Amazon of Mars) presides ineffectually over not one, but

two doomed races. Travelling to the city of Kushat with a magic

talisman, he's unable to get his warnings of invasion heeded, nor is he

able to beat back the invasion. Fleeing with some Kushati, they seek

out lost race of primeval Martians only to find they're more decadent and

helpless than the Kushat. These lost Martians give out super-weapons

when asked, but the weapons no longer work, their civilization no longer

functions, and they're simply playing sadistic games in the boredom of

their twilight. Stark's only contribution is to hasten their extinction.

In a conversation, Stark reveals himself to be an aimless, purposeless

drifter.

Indeed, to the extent that they have any effect at all,

Brackett's protagonists tend to wind up hurrying the inevitable fate along,

their own efforts to survive or change things accelerating the pace of

doom. The destruction of the Talisman Martians by Stark is one example,

the fall of Shondakar another. Even Rick Urquhart in Nemesis From

Terra is often trapped helplessly, watching allies or enemies die around

him.

In the end, Brackett's Martian heroes seldom really win.

At best they survive, often burdened with painful and hard won knowledge,

events surge past them, good intentions lead to disaster, a strong sword

arm is overwhelmed by tides of circumstance and naive optimism and good

nature is broken on the rocks of bitter wisdom.

Ladies and Gentlemen, this is not cheerful reading.

Brackett's Mars is not really about heroism or adventure.

Rather, its about tensions.

In her Mars, the Earthmen have come, not as isolated adventurers

joining the society, but rather, in the phase of traders and conquerors.

John Carter and Ulysses Paxton go native, finding a place within Martian

society. But Brackett's new generation is a different breed, and

her new age is a different place.

Eric John Stark is a rootless wanderer, rejecting Earth,

he finds no real home on Mars. Burk Winters is an Earthman through

and through. Rick Urquhart is a grifter and hard man, born

in space he doesn't belong on Mars, or on Earth, or anywhere.

But the real interloper on Mars is not the individual Earthmen, who are

struggling along. Rather, it's civilization.

Earth

has come to Mars, and particularly, Euro-American Earth. Kahora

is established as a trade city, a vast domed town created as an outpost

of Earth and Commerce upon Mars. Spaceports are built.

Trading corporations are established. Sometimes the intervention

is well meaning, as with the Doctor in Mars Minus Bisha, and the

archeologist in

Purple Priestess of the Mad Moon. But always,

it is an intervention, it is Earth imposing its ideas, its values, its

way of life on Mars.

Earth

has come to Mars, and particularly, Euro-American Earth. Kahora

is established as a trade city, a vast domed town created as an outpost

of Earth and Commerce upon Mars. Spaceports are built.

Trading corporations are established. Sometimes the intervention

is well meaning, as with the Doctor in Mars Minus Bisha, and the

archeologist in

Purple Priestess of the Mad Moon. But always,

it is an intervention, it is Earth imposing its ideas, its values, its

way of life on Mars.

Earth is in charge. In Secret of Sinharat,

Eric John Stark is enlisted by colonial police in a plot to meddle in Martian

politics. The city states are allowed their nominal independence

and isolation, but commerce on the planet, the reins of the economy, and

interplanetary trade are all firmly in the hands of Earthmen.

Martian ways and institutions survive. But the true measure

of real power is seen in Return to Sinharat, where the Earth colonial

government is beginning an ambitious planet-wide scheme of water diversion

which would require relocating entire cities and peoples.

Nope, the locals are definitely not running things.

Rather, they are shouldered aside, to stew in impotence and resentment.

Indeed, in The Nemesis From Terra, the remnants of the Martian old

guard are outright murdered.

And the Martians resent it. In Beast Jewel

of Mars, the hatred and resentment of the Martian nobility of Valkis

is clearly on display, as is a sort of anti-Earth underground movement.

Hatred or dislike for terrestrial humans is a running theme, showing up

in almost every story and novel. Secret of Sinharat, The

Nemesis From Terra and Road to Sinharat all feature attempts

at planet wide rebellions against Earth and Earth influence.

In short, the landscape of Brackett's Mars is the familiar

landscape of the British East India Company, French Indochina, the Dutch

East Indies, the European ‘protectorates’ in Africa and the Middle East.

It's a landscape of colonial traders and armies, co-existing uneasily with

a subjugated but still functioning local civilization.

Her stories are about the politics of Empires and slaves,

of the tensions and twisted relationships between the strong against the

weak, the foreign versus the local, the interlopers versus the natives,

the advanced against the primitive. There's an uneasy,

queasy dynamic, full of arrogance and resentment, a vibe where even good

intentions can amount to futile gestures, where heroism is irrelevant and

hatred is an undercurrent.

Indeed, perhaps in some ways, the sorts of dynamics and

tensions that fuel her stories may find their roots in more primal tensions

-- the conflicts inherent in being a woman in a male dominated patriarchal

society.

Yes, Brackett's version of Barsoom really is all about

Space Man's Burden, but she's not nearly so jingoistic as H. Beam Piper

in Uller Uprising,

or other more unconscious galactic empires. Rather, her work

seems fascinated with the intractable emotional tensions inherent in these

situations, tensions that paralleled her own situation.

I don't think that Brackett saw her Martian stories in

terms of her personal sexual/social dynamics. To the extent

she seemed to identify with anyone, it was with people like Eric John Stark

or Matt Carse, people whose situations had put them on the fringes, not

accepted in the dominant society, but not truly fitting into the subordinate

society either. I don't think she identified fully with her

Martians, not in the way that Burroughs did. But rather, I

think she sympathized with them, seeing a similar dynamic to social tensions

around her.

Matching

Burroughs to Brackett

It strikes me that the similarities are so profound between

Burroughs' and Brackett's Mars, that it might be more productive for us

to try to explain the differences between the two versions of Mars.

I think that the biggest difference between the two is

in the eye of the beholder, it's one of perspectives.

Burroughs, I think, fully identified with his Martians.

His stories are very much on the inside, looking out, and they accept without

questioning the Martian values and views of life. His characters

took it for granted that they should fight half way around the world for

love, or duel to the death for a personal slight.

Brackett's stories contain more distance.

We still see much of Barsoom in the world that she draws, but now it's

from the eyes of a foreigner. ‘What's with all these swords?

These people are way too willing to kill each other. What's with

the resentment? The clannishness? Seriously, you want to duel

to the death over ...that???’ Brackett's Mars is often depicted

at arms length, the strangeness and insularity, the clannishness of the

Martian society is viewed by people who are remote from it, and viewed

by people the society resents.

What it amounts to is a point of view. If

we looked at the adventures of Tan Hadron in Fighting Man of Mars

from the same sort of perspective that Brackett employs, Hadron's adventures

become darker and more conflicted, his motives become almost middle eastern

and feudal, his actions more fatalistic. He isn't a young man

off on an ill-considered adventure, but a feudal zealot on a mission of

honour so culturally ingrained it's barely conceivable for us.

This sort of leads me to argue that Brackett's Mars basically

is Barsoom, it's merely Barsoom from a different point of view, and different

point in time.

Brackett's Martians seem more clannish and tribal than

Burroughs Martians. Things seem rougher and more hard bitten.

Is it simply that difference in the observer's perspective?

Yes. But there's more going on.

Look at who Burroughs writes about: Princesses and

Fighting men, nobles and heroes, the scions of Helium and Gathol.

He writes about men who can simply commandeer flyers and warships, men

and women at the upper levels of their society and whose societies are

at the top of the Barsoomian heap.

Brackett on the other hand, sets her sights considerably

lower. Basically, it's Thug Life. Eric John Stark

is no John Carter. Rather, he's a self destructive loaner and

low life, out on the fringes of society. His friends are thieves

and brigands, literally. His milieu, the world he moves through,

are mercenaries, barbarians and cutthroats. With no real direction,

he's an aimless wanderer. The cities he visits, dead Sinharat

and isolated Kushat, are at best backwaters and boondocks.

In both of his adventures on Mars, Stark hangs out with

or deals with the nomadic barbarian tribes. They show up a lot.

Barbarians surround doomed Shondakar, and confront Rick Urquhart in Nemesis

From Terra. Mars Minus Bisha features a child dropped

off by nomads. Road to Sinharat has the protagonist sneaking

past nomads and seeking shelter with an old grave robber pal. Matt Carse

from Sword of Rhiannon is a low life bullying other low lifes. Only

in a few stories, The Beast Jewel of Mars, Nemesis From Terra

and People of the Talisman do we encounter the Martian nobility

and royalty. It's not a long acquaintance, they're foreign

to and removed from the protagonists. In Beast Jewel they're drug

runners, in Nemesis they're bitter exiles plotting a return to glory and

getting slaughtered in the process, and in Talisman they're simply petty

fools completely out of touch.

Mostly, what Brackett writes about is the seamier sides

of Martian life, the more archaic and traditional peoples on the margins

of the Martian mainstream. Basically, she's just writing a

different class of people.

Let's face it, John Carter would never be found in Madame

Kan's house of pleasure. I think he'd be shocked it exists.

Despite all this, it really does seem that the Martians

of Brackett's world are a more dour, more hard-bitten, more tradition bound

and in many ways more primitive or less technologically or socially sophisticated

people than those of Barsoom. Their culture seems narrower,

and the people more intrinsically hostile and suspicious. Perhaps

they really are subtly different from John Carter's people?

Even if we accept this, in the following chapter, I think

that we can explain the process by which Barsoomian culture shifts subtly

from that known by John Carter to that seen by the Earth Colonialists.

However, before we get into that, I just want to make a few observations.

There's no sign of Green Men of course. But then,

there doesn't need to be. Their ranges and areas are well defined,

and they're probably rare outside their tribal territories.

I could see that their ferocious prowess and implacable natures might leave

Earthmen giving them a wide berth.

That still leaves a lot of space for human nomadic tribes

in some areas. Indeed, in Otis Adelbert Kline's Outlaws

of Mars, we see that there are human nomadic tribes around the hinterland

areas of Khalsifar and Xancibar. So the existence of such tribes

is not a barrier to Barsoom.

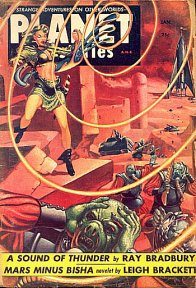

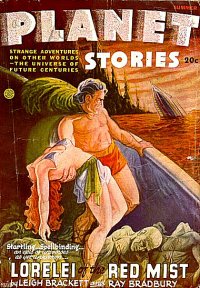

The

Brackett Martians seem to be ethnically different. Let's face

it, Burroughs doesn't spend a lot of time on eye colour, so we don't know

what the colours or ranges for the Barsoomians are. Brackett's

Martians often sport yellow or golden eyes, which seems an obvious Bradbury

reference. Brackett and Bradbury actually collaborated on a Venus

story, Lorelei of the Red Mist.

The

Brackett Martians seem to be ethnically different. Let's face

it, Burroughs doesn't spend a lot of time on eye colour, so we don't know

what the colours or ranges for the Barsoomians are. Brackett's

Martians often sport yellow or golden eyes, which seems an obvious Bradbury

reference. Brackett and Bradbury actually collaborated on a Venus

story, Lorelei of the Red Mist.

(Looked at another way, Brackett's Mars straddles a midpoint

between Burroughs' Mars full of Martians and Bradbury's Mars in which the

Martians have passed away leaving ruins and memories, and humans are left

to confront themselves. She straddles a border where the Barsoomians

and Earthmen uneasily contemplate sharing a world with each other.)

Burroughs writes that the dominant population is copper

skinned or ‘red’ but then spends a lot of time discovering races and enclaves

that prove him wrong. So I've argued, and it's quite likely

that there's more racial variation than we've seen. So the

olive skinned or weather darkened Martians might simply be a different

regional blend of the Red race.

There's no indication of Barsoomian longevity. Or

is there? In The Secret of Sinharat, there's a throwaway

line: "Kala might have been beautiful once, a thousand years

ago as you reckon sin." Perhaps fact, perhaps hyperbole.

The critters that they ride may be thoats.

Or perhaps not. Brackett never bothers to give them a name,

or any sort of description. All we know of them is that they're scaly

hided, bad tempered, hissing, or squealing and large enough to ride or

for a team to draw a canal boat. In another spot, they're referred

to as rangy beasts with padded hooves. Another point there's a reference

to a flesh comb that serves as a forelock. It's possible that in

some remote areas of Mars different animals than thoats may be domesticated

for riding. In Synthetic Men of Mars and the Giant

of Mars for instance, the Malagor, a giant swamp bird, replaces the

Thoats.

There

is one reference to a clearly Burroughsian creature: A Martian Sand-Cat

or Sand-Leopard appears in The Halfling. The creature

is described as feline in appearance or nature, about the size of an earth

leopard, and it has six legs.

There

is one reference to a clearly Burroughsian creature: A Martian Sand-Cat

or Sand-Leopard appears in The Halfling. The creature

is described as feline in appearance or nature, about the size of an earth

leopard, and it has six legs.

Fliers are occasionally seen, but never described.

The most significant aspect of this is that the term used is the Barsoomian

‘flier’ rather than airship, spaceship, aircraft, plane, etc.

Although she writes frequently of Mars, Brackett shows

us relatively few of the cities and towns. Barrakesh straddles

the equator. Barrakesh, Valkis and Jekkara are all cities on

the same canal in the Southern Hemisphere, near a former sea.

Valkis and Jekkara were originally on the shores of the ‘White Sea’ and

Jekkara has hills behind it to the east. Barrakesh straddles

the equator, and to the north of them there are the barbarian tribes of

Kesh and Shun. Within the territory of the Barbarians are the dead

cities of Shondakar and Sinharat. There is a city called Ruh, capital

of some ancient long gone Empire. Kahora is a trade city built

by Earthman. Somewhere in the far north is a small, isolated city

of Kushat, surrounded by the barbarian Mekh, and its neighbor the more

substantial city of Narissan. Taarak are a northern hemisphere Barbarian

tribe on the other side of the world from the areas of Shondakor.

Okay, cool. The thing is, Burroughs gave us

new cities with every book. There seems no obvious reason that

we cannot fit these into Barsoom somewhere. Indeed, Jekkara

might well be a sister city to Jahar, as we'll explore later.

Of course, the question arises as to why we hear about

Jekkara, Valkis and Ruh as dominant cities in Brackett's stories.

If Brackett's world really is Barsoom, where is Helium, Ptarth, Kaol and

Gathol?

I think that the real explanation there may go back to

these being the cities that Earth has the most access and most influence

in. Helium is around, but like Thailand or Japan or Persia,

keeps Earth and Earthmen at arms length. Earth's influence

tends to be strongest at vulnerable points.

Tharks

in Space

We don't find Tharks on Brackett's Mars. Brackett

never mentions a race of giant four-armed green Barbarians.

Fair is fair, if she had, the copyright lawyers would have been right on

her tail. Tharks are just too distinctive for anyone else but

Burroughs to use and get away with.

Instead, Brackett's barbarian nomads, as with Kline, are

standard Martian humans. Hard-bitten, a bit wild, but definitely

human and part of the greater culture. Her nomadic tribes include

the Kesh, the Shun, the Mekh and the Taraak. Let's think Mongols

and leave it at that.

But interestingly, The Nemesis From Terra does

have a counterpart to Burroughs' Great White Apes. Rick

Urquhart is pursued by black apes, strange martian anthropoids, no larger

than human, but clearly non-human and dangerous. Their description...

"A black anthropoid from

the sea bottom pits, one of the queer inhabitants of an evolutionary blind

alley you were always running into on Mars. Some said they had once

been men, and degenerated in their isolated barren villages. Others

said they were neither man nor ape, just something that got off on a road

that went nowhere. Rick didn't care much. All that interested

him was that the black apes were trained now like hounds....

Four black shadows came slipping on silent paws... He went down under

a weight of sinewy bodies, beast quick, strong, with the musky smell of

the furred animal..."

So are these the four-limbed or six-limbed variety of apes?

Regular apes, or relatives of Burroughs Great White Apes? Mutated

degraded descendants of Caer Dhu? Or perhaps relatives of the

black apes found in Gullivar Jones? She doesn't say.

That's all we get. Typically, Brackett stints on the description,

perhaps encouraging the reader to fill in the blanks themselves, depending

on how close or how far they feel they are from Barsoom. This

sort of thing actually occurs fairly often in Brackett, the woman just

ain't big on description, which suggests that she's relying on our familiarity.

Writers like Otis Adelbert Kline, Ralph Milne Farley and

Lin Carter, if they did not place four-armed giants on Mars, still managed

to sneak races of four-armed giants, some of whom bore very suspicious

resemblances to or ancestry from Martian Green Men, onto other planets.

I've touched on some of these elsewhere, particularly in Tharks in Space.

Do we find races of four armed giants in other planets

in Leigh Brackett's solar system? Not quite. But we do

find apparently two races of four-armed humanoids. Quoting

from the Wikipedia:

Venus:

Lohari Not much is known about this rare reptilian species;

they live in the Lohari swamps, have four arms each, and crawl like serpents.

(The Citadel of Lost Ships)

Callisto: Callisto possesses

two quite distinct intelligent species. One type is humanoid, though smaller

and thinner than humans, and with four arms. These Callistans have scarlet

eyes, white fur, and scarlet feather-like antennae atop their heads. They

possess psionic abilities that they can project through the music of specially

designed instruments (The Citadel of Lost Ships).

Dwarf

Tharks? It's notable that both of these races appear or are

mentioned in the same story. Without actually having the story before

me, I can only speculate that they may be related. It's possible

that someone has misread the story and that there's only one four-armed

race. Although smaller than humans, they Callistan humanoids do have

some psychic talent which might imply that there's relationship with the

telepathic green martians.

Dwarf

Tharks? It's notable that both of these races appear or are

mentioned in the same story. Without actually having the story before

me, I can only speculate that they may be related. It's possible

that someone has misread the story and that there's only one four-armed

race. Although smaller than humans, they Callistan humanoids do have

some psychic talent which might imply that there's relationship with the

telepathic green martians.

Another story, the Halfling contains six-armed,

mentally deficient ‘geeks’ with armour-plated backs, and a reference to

six-armed geeks with antenna. As always, we wonder if the reference

isn't mistakenly six-armed for six-limbed.

Not much, but there it is. The question with regard to

Callisto is, can we reconcile these local aliens with the Thanator depicted

by Lin Carter? Well, yes and no. Certainly Carter never

mentions such creatures on his Thanator. But then again, he's also

carefully left large parts of his planet unexplored.

Linguistic

Connections to Barsoom

Following up on Linguistic

Archeology and Orovars, an essay I wrote here, (somewhat related to

an essay I wrote on the evolution

of religion on Barsoom).

A word or two about this subject. I think

I'm getting a bit carried away at points. It's a fun bit of

gamesmanship, but really, how much weight can we put on it?

First, let me say that Burroughs himself put quite a bit

of time and effort into manufacturing his Barsoomian language, and using

it consistently and reliably. Burroughs was big on notes and world building,

and he was hardly reckless in doing so. He created not just

a Barsoomian language, but a fairly full vocabulary for Mangani and Pal-Ul-Don,

and even dabbled a bit with language in Pellucidar, Venus and Caspak.

He created elaborate glossaries or dictionaries for both Pal-Ul-Don and

Barsoomian, which means that he actually did sit down and work these things

out.

He was not a stupid man. He knew and understood

English very well, and he was exposed to other languages and had an opportunity

to grasp that languages operated with fundamental underlying rules, that

words were often cobbled together out of other words, and that a single

word might form a root going off in all sorts of directions.

He could see the influence of history on words and names, and indeed, on

the naming of geography and places.

What this resulted in, was that he tended to use his fictional

languages very consistently, and that he seemed to be employing or applying

rules and constructions which might not be articulated out loud, but that

nevertheless showed up over and over. This was consistent, not just

within his language, but within the world that he built. I'm not saying

that he sat down and crafted the whole thing overnight, or indeed engaged

in a systematic process. I think that Barsoomian was kind of

an evolving thing for him, he just kept making notes, and reviewing notes

to make sure that his new words and concepts were consistent with the old

ones.

Tor, Tar, Thur and Thar came up a lot, simply because

he liked the sound of them, and perhaps some inspired others.

It's not a stretch to decide that relatives of the Thark green men might

have cousins with similar sounding names like Thurd. After

a while, he needs to come up with a name for an archaic God.... Well,

he's already used a lot of Tur sounding words for archaic place names,

and this suggests the name for the archaic god. It's a backwards

effect, but it's a real process, which also tends to support analysis.

The point is that whether Burroughs language process was

deliberate or unconscious (and I'd argue for a mixture), it produced a

coherent body of language and linguistic rules that was consistent enough

that we can analyze and deconstruct it, as we did in Orovars and Linguistic

Archeology.

Now, here's where it gets interesting. What

I've found through other works, is that we can take the linguistic rules

of Barsoom and apply them to other Martian novels and stories, such as

Otis Adelbert Kline's, and they seem to work. That is, place

names, words and terms found in writers, including Arnold, Tolstoy, Kline,

Lewis and Carter, seem to harken back and make sense when we apply Barsoomian

rules.

Partly, this is because the units are often so basic.

I'm working with syllables and phonemes. Partly there's a certain

amount of cheating going on, because I'm prepared to be flexible, allowing

for both different written versions of the same or similar sounds, and

for natural linguistic drift.

In some cases, as with Arnold and Lewis, this is probably

(but only probably) coincidence. In other cases, I'm not so sure.

The thing is, that when we look at writers like Kline,

Carter, Brackett and even Tolstoy, we can say with certainty that we know

they were exposed to and heavily influenced by Burroughs and Barsoom.

Absolutely no question of that. So when they write their own

Mars novels or stories, that writing is itself influenced by Barsoom, and

they find themselves automatically or unconsciously coming up with words

that are ‘barsoom friendly,’ words that feel right for Mars.

I don't think that they sit down, pore through Barsoom

glossaries, dope out syntax, deconstruct the linguistic rules and apply

them to make new words, or place their old words properly. That's just

silly. But what I do think, is that in reading the Barsoom stories, they

absorb the flavour of the words and unconsciously absorb meanings and linguistic

rules, which become part of how they think creatively about this world

and develop their own ideas and words.

That's not a big stretch. I've caught Otis Adelbert Kline

using a mangani word in his own universal primate language in Tam, Son

of the Tiger. Lin Carter in his Callisto series winds up using a Barsoomian

word for unit of measurement as a measurement word on his Thanator, and

he makes no bones about seeking phonetic resemblances to harken back to

Barsoom in his fantasy series. So I think it's pretty well

established that it does go on.

Of course, writers make up their own words and linguistic

rules unrelated to Burroughs Barsoom, but that's fair. The

point is not to say that it all has to derive from Barsoom, but merely

to say that we can find Barsoom in it.

So what about Brackett? Can we find Barsoom's

linguistics in her own Mars?

Well, first, take a look at some of her places: Barrakesh,

Kesh, Jekkara, Vishna.... Yeah, these are obvious plays on

Marrakesh, Cush, Sahara, Vishnu.... Middle eastern or Oriental names

or places. What does this tell us? Basically, that

Brackett isn't reaching very deep, she's basically working off the top

of her head, picking up whatever sounds exotic. Much has been

made of the gaelic influences in her Martian names, but really, this is

just more of the same. She's just reaching for whatever is

easy and obvious for her. So this includes gaelic and middle

eastern or oriental words. She's not busting her ass coming up with

words, or with linguistic rules. She's basically skimming off

the upper levels of her subconscious, or the lower levels of her consciousness.

Well, follow that thought. The more unconscious

your process, the more likely it is that you're just going to be picking

up on whatever is lying around and handy, isn't it? And we've

already shown that Barsoom was incredibly influential on her picture of

Mars. At least as, and likely far more influential on her Mars than

her knowledge of gaelic history or middle eastern culture.

And Barsoom has a large set of words and linguistic rules that would have

seeped easily into the back of her mind.

So, logically, what we'd expect to find would be a close

linguistic affinity between Brackett's Mars and Barsoom. We should

be able to find words all over the place which employ Barsoomian concepts

and constructions. And in fact, we do...

I should acknowledge, on Brackett's behalf, that she never

employs a bona fide discrete Barsoomian word that I can find.

On the other hand, she's pretty cagey with her Martian language.

Although the Martians are clearly depicted as an alien culture, and with

a distinct psychology, values and outlook, we don't get a lot of alien

words to represent that distinctiveness.... Practically none.

Her Martians refer to Mars as ‘Mars’ and not by a local word.

Phobos and Deimos have Martian names, but in most stories, even the Martians

refer to the moons by their Earth names. We don't get the Martian

word for Princess or King. We're never told the name of whatever

the hell that reptilian bad tempered thing is that Eric John Stark and

others are riding around the desert on, or if we are told, it's not used

very often.

In short, we get very little Martian language from her

at all, amazingly enough. I sat down and made a count, and

through four novels and six short stories I found a total of four, only

four, Martian words which were not personal names, place names or tribal

names. This is particularly remarkable when we realize that in terms

of number of stories or word counts, she's somewhere in the vicinity of

Barsoom itself in terms of sheer volume.

But then, this is an irritating, or perhaps helpful thing

with Brackett. She seems more than content to rely upon the

audience's knowledge of and assumptions about a world that, if it is not

actually Barsoom, that is close enough that an audience will fill in the

blanks themselves. So she doesn't go out of her way to clutter

up things with descriptions which might undermine that ‘filling in the

blanks as Barsoom or pseudo-Barsoom.’ So if the warriors

wear harnesses, well, we don't hear much more about it, they ride about

on steeds which aren't described, and their fliers are vague references.

Of course, the thing is, if you're resting that heavily

on Barsoom, and leaving so many things blank, well, don't blame me if I

find it very easy to fold your fictional Mars back into the fictional landscape

that you took it from originally.

You know, it occurs to me that since I've written Linguistic

Archeology, I've peppered these sorts of linguistic analysis as chapters

into a handful of other essays. Same thing with the geography

of Greater Barsoom, a few core essays, and then subdiscussions in a bunch

of

other essays. I think perhaps one of these days, if there's

any interest, I should go back and pull them all together and put out a

couple of comprehensive essays on the Language of Greater Barsoom,

and Geography of Greater Barsoom. Perhaps throw in a

Greater

Venus, and Greater Pellucidar essay. Ah well, not

here, not now.

But onwards, back to Leigh Brackett and Barsoomian linguistics:

As I was saying, I think we can actually find connections between the words

and word roots in Brackett's Mars and Barsoom to suggest that they may

well be the same place...

The key in Linguistic Archeology was to examine Burroughs

Barsoomian language for recurring patterns. Repeated uses of root

words that could be found in prefixes or suffixes or in the body of a word.

Some of these were given to us directly by Burroughs,

who seems to have clearly intended that adding a suffix 'a' or 'ia' to

a name meant that it was a daughter. Thus 'Thuvia' is the daughter of 'Thuvan.'

This is the most obvious and commonly remarked observation about the Barsoomian

language. But there are other things we can figure out, which

suggests that Burroughs was using consistent linguistic rules consciously

or unconsciously.

Other words or word roots were used consistently enough

that we can dope them out fairly easily. 'Than' is a warrior. Panthan or

'Pan Than' is a mercenary, Gorthan or 'Gor Than' is an assassin.

To this we could probably add Utan or 'U Than' which is a rank of command,

assuming that the 'Tan' is a modified 'Than'. And working from that, Jetan

becomes 'Je Than' about a game of warriors Barsoomian chess.

See the pattern. There's a common root, 'Than', which

clearly means fighter or warrior. If we assume some degree of pronunciation

drift (regional accents, differences in pronunciation over time, etc.),

we can relate it reasonably to usages in other similar words where the

fundamental meaning of 'warrior' seems to be continued. So, with 'Than'

we've got a useable root word of original Orovar (an ancestral race of

Barsoom).

From there we could look at 'Pan' or 'Gor' to determine

if these roots show up elsewhere, and if we could derive a common meaning.

Take 'Pan'. This shows up in the northern polar nation

of Panar and its city, Pankar. It also shows up in the personal name Pan

Dan Chee (a relic Orovar from Horz), and Pandar (a phundalian warrior),

its use in names being found in archaic cultures.

From there, we make a guess, that Pan may be a very ancient

word, perhaps meaning wanderer, or in some uses, refugees. Which suggests

that Panar may be Pan R or 'Refugees of R', and the city of Pankar may

be 'Children of the Refugees'. Pankar is a domed city of Red Men, similar

to the domed cities of the yellow O Kar. The O Kar cities were founded

by refugee yellow men fleeing north. So Pankar and Panar were themselves

likely refugees, 'wanderers' as in people fleeing. Possibly, Pankar

was originally a yellow city of different name, overwhelmed by a nation

of red refugees. It does seem to fit.

Sometimes, we might not be able to guess at a meaning

in a root, but we can see it showing up often enough or consistently enough

to identify it as a significant root word without quite knowing what it

means.

Anyway, in Linguistic Archeology and Orovars, we found

certain recurring linguistic themes or artifacts, which we can apply to

Brackett's Mars, suggesting that there are is a linguistic connection or

identity between the two versions of Mars.

As I've noted, frustratingly, or conveniently, as you

choose, Brackett gives us almost no Martian words. There's

Shanga, a reversion ray; Yril, a sort of wood; Getak, a game, and Thil,

a narcotic drink.... And that's it for the stuff I've managed to

read. There are no words for animals, clothes, common objects, special

rituals, whatever. She never even gets around to naming the

riding beast.

Apart from those four words, there are only a scattering

of place and tribal names and a score of personal names. So,

most of this discussion will tend to focus on place names, with a few allusions

here and there to personal names.

One of the most common and crucial words in Barsoom relates

to the ancient religion of Tur. A great many place names, numbers, titles

and personal names can be related back to Tur or its variants, Thur, Tor,

Thur, Tar, Thar... With Brackett, we see a few examples of 'Tur-ism' in

place names for cities and tribes:

Kathuun = Ka Thu (Tur) N

Taarak, Tarak = Tur A k

(Thark?)

Tur-ism also shows in at least a few personal names:

Thord (Tur-D), Tor-Esh (Tur-Iss), Otar (O-Tur), Thorn (Tur-N)

There seemed, in Barsoomian, to be a caste of derivative

words or roots that may have originally related to and drived from Tur.

These include Zar (meaning loosely, sky, sun or home), Kar or Kor (children

or perhaps followers), Far and/or Var (meaning people), Tar or Ther (possibly

holy, people or holy people), Bar (ground, land), Hor (city), Dar

(great or many, large number).

So, looking at some of Brackett's place names, we can

break them down into Barsoomian roots and analogues.

This allows us to take a hard look at some of Brackett's cities and tribes:

Jekkara Ja Kar A.

We've established that the 'a' denotes daughter, and Kar denotes people.

The 'Ja' is also found in Barroom's Jahar (Ja Hor, City of Ja), Tjanath

(Ja Nat), Jasoom (Ja Soom or Earth).

Ja or Jah is also a very very common name component, as

in Dejah or Sarkoja. 'Je' may be a variant pronunciation, which shows up

in Jetan, Jed and Jeddak. The implication might be that Ja or Je could

mean 'high' or 'noble' or perhaps ‘king.’ Thus, Jekkara would

translate into Barsoomian as 'Noble People's Daughters'.

And by extension, this would give us a full translation

for the Barsoomian Chess game of Jetan: Ja-Than = Ja (Noble)

+ Than (Warrior) or Nobles & Warriors. Sort of literal,

kind of like ‘Snakes and Ladders’ or ‘Dungeons and Dragons.’

Brackett's story ‘The Halfling’ refers to a Martian came called Getak (Je-Tak

or Ja-Tak?) which may be a variation on Jetan.

This deconstruction suggests that Jekkara may well be

related both geographically and culturally to Jahar or 'Noble City', and

Tjanath. Indeed, it may have inherited regional hegemony from

Jahar after the sack of that city and the catastrophe of U-Gor in Fighting

Man of Mars.

Then there are the two cities of Caer Dhu (the Caer Dhu

of the serpent men from Sword of Rhiannon, and presumably a later Caer

Dhu occupied by humans which was destroyed by shanga reversion as noted

in the Beast Jewel of Mars), and Caer Hebra, a surviving city of

winged people. The ‘Caer’ is obviously a gaelic allusion, but

I'd translate it phonetically as either ‘Kar’ or ‘Sar’. So,

basically, it's a dressed up version of what has become some very familiar

Barsoomian terms.

Caer Dhu is also interesting because its suffix, Dhu (or

Du), is reminiscent of Burroughs Barsoomian cities of Duhor (Du-Hor) and

Dusar (Du-Sar). Otis Adelbert Kline's Swordsman of Mars

also features a third city, probably in the same general region, Dukor

(Du-Kor). We might be able to infer some sort of broad relationship

in geography or history between the four cities of these three writers....

Though clearly, three of them are humans unrelated to the extinct Dhuvians.

The prefix ‘Du’ also appears in The Last Days of Shandakor,

in a personal name, Duani, or Duani. Shandakor, in mind of nothing

in particular, is also close to the name of a city of Lin Carter's Callisto,

which has its own Barsoomian connections.

Sark (Sar K), is an ancient empire

in Sword of Rhiannon, so it seems to be an old and traditional name.

Sark also shows up in Otis Adelbert Kline's Sarkiss in ‘Outlaws of Mars.’

Meanwhile, Lin Carter's ‘Flame of Iridar’ features a character named Sarkand,

also from ancient times. Sar or Zar features prominently in

Tolstoy's 'Aelita: Princess of Mars'.

There are a few other interesting place names in Brackett,

which seem to use Barsoomian roots or Barsoomian constructions.

Kahora (Ka Hor A)

(Kar Hor A?) (People's City of Daughters?)

Varl (Var L)

Quiri (Kar E)

Kharif (Kar If)

Karadoc (Kar A Doc)

Karthedon (Kar-Tha-Don)

Khondor (Kon-Dor)

Quiru (Kar-U)

Sark (Sar-K)

There are also a few Barsoomian names: Kor

Hal, Kardak (Kar-Dak), Corin (Kor-In), Narrabar (Nar-A-Bar), Penkawr (Pan-Kor

or Pan-Kar)

Interestingly, where in many of the place names of Burroughs

Barsoom, we found frequent references to Tur (including variants: Tor,

Thor, Thur, Thar, Tar); many of Brackett's Martian cities seem to contain

variants of Iss. We might actually expect this, when you think

about it. After all, if Tur really had such influence in the naming

of geographical features, we might expect the later Iss cult to have its

own ‘naming’ urges.

Valkis (Val K Iss)

Barrakesh (Bar A K Iss)

This is interesting because of the root Bar, which seems to be Land. The

translation would be 'Daughter Land of Iss'.

Narrissan (Nar Iss An) (Nar-Iss-Zan?)

Kesh (K Iss) A barbarian tribe in the southern

hemisphere.

Shun (Iss Un) A barbarian tribe in the southern

hemisphere.

Of course, although Brackett doesn't give us the local

Martian name of Mars, she does give us the names of the moons, and uses

them once or twice. And they're not Thuria and Cluros. They're

Denderon and Vishna. Problem...?

Well, even on Earth, we have different names for our satellite

'the moon' and 'luna', so perhaps its not entirely fatal.

It may well be that Barsoomians may have multiple names for their own moons.

Phobos is, in Burroughs world, called Thuria, or Ladan

by its inhabitants. On Brackett's Mars its called Denderon.

Meanwhile, the second moon, Deimos, is called Cluros by Burroughs and

Vashna by Brackett.

Let's deconstruct this a bit. Cluros breaks down into

two words: 'Clur' or 'Klur', which may be a variant of 'Kar' meaning child

or children; and 'Os' which may be a variant of Iss. Thus, while Thuria

can be easily translated as 'Daughter of Tur', Cluros might translate as

'Child of Iss.'

Vashna may have a very similar meaning. Its central syllable,

'Ash' may be another variant of 'Iss.' The 'a' attached as a suffix denotes

female or daughter. So Vashna might translate loosely as 'Daughter

of Iss', which is very close the meaning of Cluros, and related to the

meaning of Thuria.

On the other hand, Brackett's counterpart to Thuria is

Denderon. Here, we are not on solid ground in finding a true parallel,

though there are some interesting things.

'Den' doesn't appear at all in Burroughs, though 'Dan'

appears as a root in Zodanga and in personal names like U Dan and Pan Dan

Chee, but unfortunately, a meaning eludes us. Most significantly, 'Dan'

appears most significantly in the place name, Ladan or La Dan, the Tarid

(local inhabitants) word for Phobos. So, possibly it's a significant word,

but we can't quite figure it out.

'Der' may be related to 'Dar' which seems to be a religious

root for large. Perhaps a reference to Thuria's distance or being the larger

moon? At best, we might find a loose parallel to the Thurians own name

for their world, Ladan or 'La Dan' to 'Dan Dar N'

In Brackett's stories, there are occasional references

to ruins left behind on Phobos. As we know, in Burroughs stories,

Phobos (Thuria) is actually inhabited. This implies that sometime

between John Carter and Eric John Stark, something very unpleasant and

final may have happened to the inhabitants of Thuria. Itself

a hint that greater and more wide ranging changes have been at work.

What does this all amount to? Well, obviously,

Brackett's Martian places and names seem to fit neatly into Barsoom without

much trouble at all. Which only goes to emphasizing that Brackett's

Mars and Burroughs Mars are essentially the same place, though at different

times and through different viewpoints.

Brackett's

Future History of Barsoom

The critical difference between Burroughs' Barsoom and

Leigh Brackett's Mars, the difference that everything else flows from,

is time.

Burroughs Barsoom chronicles the adventures of John Carter

and his allies from approximately 1865 through to about 1945.

Essentially, they're told in contemporary time, encompassing the late 19th

and early 20th centuries.

Leigh Brackett's Martian stories take place much later.

Her short story collection, 'The Coming of the Terrans' gives a series

of dates on each story title, ranging from 1998 to 2038. On

the other hand, these dates aren't referenced in the stories themselves,

which seem to connect to or relate to stories much later. At

the

earliest, we can set Brackett's Mars stories as beginning in the 21st century,

several decades after John Carter.

Eric John Stark occupies a cluster of stories set on Mars

and Venus. Stark's other Martian story, seems to refer indirectly

to the events of the Beast Jewel of Mars, dated 1998. One of the

stories in the 'Coming of the Terrans' collection is 'Road to Sinharat'

dated as 2038. But this story seems to occur later in Brackett's

history, years after the events of the Secret of Sinharat, featuring

Eric John Stark.

If we go by the dates set in 'Coming of the Terrans' this

seems to suggest that Stark's period of activity is somewhere between 2010

and 2020. This really does seem way too early, perhaps by as

much as a century. Stark would have to have been born in the 1980s.

His history was an orphan raised on Mercury, which suggests that early

exploration colonization of the inner solar system by Earth probably dated

as far back as the 1960s. That simply doesn't seem feasible.

Given this, I'd tend to regard the dates given in the story titles as interpolations

and unreliable. I'm prepared to accept the order of stories,

but not the specific dates. It's possible, I just tend to regard

it as unlikely.

The only dates which are actually given in any of Brackett's

stories are for the Water Pirates, set in the 25th century, and

Interplanetary

Reporter, set in the 26th. These stories feature a Mars

well integrated into the interplanetary trade and political network, and

relatively independent of Earth. So they're at the end of the colonial

period.

Given this, I'd suggest that the Barsoomian colonial period

probably ran from the 22nd century to the 24th. Potentially,

it was much shorter. On Earth, the Colonial period for India

dated from roughly 1700 to 1950, or about 250 years, give or take.

On the other hand, the Colonial period for much of Africa ran from 1890

to 1960, or perhaps five to seven decades.

So what happens to turn Burroughs Barsoom into Brackett's

Mars?

Well, Earth does, obviously.

In the intervening decades of centuries, John Carter may

well have died. There are indications that he is immortal or

quasi-immortal. But an accident with thoat or flyer, a lucky shot

or a quick sword thrust, might well end the life of the Warlord of Helium.

John Carter lives dangerously.

Or possibly, John Carter is still around on Brackett's

Mars, defending and preserving Helium and his allies from the intrusions

of the yankee bandits from Earth. There's nothing in Brackett

that would demand Carter start pushing up daisies. Indeed,

if we look to European colonialism, we find several states, Ethiopia in

Africa, Persia in the Middle East, Thailand in the Orient who were able

to preserve their independence from the Colonial Europeans. One of these

states, Japan, even managed to push back.

So its not unlikely that Carter is still around, and that

Helium and other allies are still maintaining some degree of autonomy and

independence. Many of Brackett's stories seem to revolve around

the weaker or prostrate city states, the vulnerable or colonized territories,

such as Barrakesh, Valkis and Jekkara. So we may simply have

a situation where some parts of Mars are more thoroughly dominated by the

terrans than other parts, and Brackett's works focus on the places where

colonial domination is most obvious.

Indeed, Brackett repeatedly refers to Mars ‘Confederation

of City States’ suggesting that something resembling the Heliumatic league

might still be around, although weakened and attenuated.

Still, its clear that with the coming of the Terrans,

Barsoom falls on hard times. So, what is probably happening?

Probably a number of things.

First, we have to consider that Barsoom during John Carter's

era is undergoing all sorts of major changes. The Iss religion

has been overthrown and discredited. But Carter himself notes

that some groups of Therns are refurbishing the cult and touting a ‘Reformed

Iss’ faith with a decidedly more mystical and user friendly angle.

It's likely that the fall of the Iss faith would open the door to a resurgence

of the Tur cult, or even to new religions and religious impulses.

Ethnically, the O-Kar, the First Born, the Therns and

even relict populations of Orovars have all been re-discovered and re-united

with the mainstreams of Barsoomian life. Therns have left Valley

Dor and now wander freely around Barsoom. The past suggested

that the ethnic makeup of Barsoom was fairly uniform. Now,

in John Carter's era, there is an increasingly more diverse ethnic background,

there's more likelihood of more colours and kinds of persons in different

areas. And the breakdown in Barsoomian's splendid isolations

suggest that we may discover that even Barsoom's red race was not so uniform

as we had thought.

There are downsides of course, the empire of Jahar pretty

much lies in ruins, and if the rest of the planet is looking good, things

are probably pretty bad for Jahar and its satellite cities.

They probably represent the weakest and most vulnerable areas.

There may be other areas of Barsoom equally devastated by wars and conflict.