Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages in Archive

Presents

Volume 1474

Burroughs' Sailor Among Apes

Georges T. Dodds

Dept. of Biosystems Engineering

McGill University, Montreal, Canada

A number of writers have speculated within books [Altrocchi (1944), Lupoff (1965), Porges (1975), Atamian (1997), Taliaferro (1999), and Kasson (2001).], peer reviewed journals (e.g., Journal of Popular Culture) and ERB-related fanzines [e.g. Camille "Caz" Cazedessus' ERBdom and Pulpdom (Nos. 8, 23, and 25)] about works which might have influenced or inspired Edgar Rice Burroughs' in his writing of Tarzan of the Apes. Introduction

Based on his correspondance with Edgar Rice Burroughs, Rudolph Altrocchi in his "Ancestors of Tarzan" stated:

There was another source for Tarzan. Somewhere, perhaps in some magazine and certainly before 1912, Mr. Burroughs read a story about a sailor who, as the only survivor of a shipwreck, landed on the coast of Africa. There he tried to make the best of a difficult situation, à la Robinson Crusoe. During this forced sojourn in the jungle, a she-ape, which he had tamed, became so enamored of him that when he was finally rescued, she followed him into the surf and hurled her baby after him. This modern story I have been unable to find. (Altrocchi, p. 95)Two issues devolve from this and the theme of Tarzan being raised by apes: (i) the story of survival of a shipwrecked sailor among friendly apes, (ii) the miscegenation of human with ape, and the consequences of the "divorce." With regard to the second question I am preparing a folklore paper which expands significantly on Altrocchi's search in these matters, particularly with respect to the 16th century origins of the tale. This will eventually be submitted the a folklore journal Estudos de Literatura Oral. However, I propose two 19th century English sources where Burroughs might have come across the story.One of the works generally cited in this context is Léon Gozlan's Les émotions de Polydore Marasquin; ou, Trois mois parmi les singes [Polydore Marasquin's Thrills; or, Three Months among the Apes] first published in French in 1856 as a serial in Journal Pour Tous, then in book form in 1857. In English, Gozlan's novel first appeared unattributed in an anthologyThe Man among the monkeys, or, Ninety days in Apeland: to which are added The philosopher and his monkeys, The professor and the crocodile : and other strange stories of men and animals. Two 1888 English translations also exist, one titled Monkey Island; or, The Emotions of Polydore Marasquin and the other The Emotions of Polydore Marasquin. However, in this work the apes and monkeys are escapees from a rather brutal (by today's standards) zoo supplier, and are distinctly inimical towards this individual when by happenstance he is shipwrecked on the same island where they have escaped. Thus besides a relationship with a small friendly chimpanzee, and saving himself by taking on an ape-like appearance by donning the skin of a large dead ape, the protagonist is constantly at risk of being killed by the other apes, particularly one which he had tortured in the past. Sailor Among the Apes

Similarly in Harry Prentice's 1888 The King of Apeland. The Wonderful Adventures of a Young Animal-trainer (also as Captured by Apes: or, How Philip Garland Became King of Apeland., a work clearly plagiarized from Gozlan's work, the story is the same.

A work that does not seem to be mentioned at all in this context is the 1908 dime novel The Young Marooner; or, An American Robinson Crusoe by Frank Sheridan (a.k.a. John deMorgan). In this very poorly (even for a dime novel) written short novel (33,000 words) sixteen year-old Tom Scott leaves home and becomes a sailor on a whaling ship. Hanging on, through lack of experience, to a harpoon cable tied to a harpoon buried in a whale, Tom is dragged off and ends up riding atop the whale and being chased by a ravenous giant squid. He passes out and wakes up on the shore of what turns out to be an uninhabitated island. After some exploring and dodging a band of pirates he meets an orang-outang (which the author names as such but insists on referring to as a baboon throughout the rest of the novel!):

In front of me, not ten yards away, stood an object whose very appearance was enough to terrify anyone.Tom goes on to befriend the orang and names him Spero (Latin for "I hope"). Tom employs him as a servant, as a retriever of game, to help him build himself shelter, and in a great number of other employments. Eventually they live together in the hut they have built. Spero is eventually joined by two other orangs, Hercules and Cupid, who similarly help out, under Spero's direction. However, all the orangs are male, so any mating aspect of the story is absent.

A great ape, or, to be more accurate, an orang-outang, stood grinning at me, but in its hands it held a club heavier than mine, and had it raised ready to strike.

I knew the orang-outang to be less ferocious than the gorilla and more intelligent than the baboon.

How was it I had not seen this creature before?

If I picked up any of the coconuts, would not the orang pounce down upon me as a thief and quickly deprive me of life?

(The Young Marooner p. 9-10)Later, Joco, a human, Friday-like character is discovered hiding out on the island. The orangs conveniently disappear. Tom and Joco discover a mysterious well leading to an underground river and tunnels to an adjacent island beneath the volcanic island. They save princess Waupango of the adjacent island from being devoured by cannibals, but her people are rigid exclusionists and try to kill the heroes when they come to their island. Tom and Joco escape, and with a powerful explosive devised by Joco — a black Jamaican ex-school-teacher, ex-pirate, and pretty good chemist besides — destroy the tunnels linking the islands. However, Joco is obsessed with the underground river and its bizarre ante-diluvian lifeforms. One day he leaves to explore further, and an earthquake seals his fate. Later, the princess, escaping an unwanted marriage and devastated at the news of Joco's death, commits suicide. Tom lives on, though with little further interaction with the orangs.

In the period that The Young Marooner was published Burroughs was a magazine ad buyer for the Physicians' Co-Operative Association, Chicago. Given Burroughs'knowledge of the pulp magazines and dime novels of the era, both personal and through his work, make it quite possible he could have come across or even read The Young Marooner. Taliaferro (p. 89) suggested on a similar basis that Burroughs might have read and drawn from William Tillinghast Eldridge's The Monkey Man in All-Story Magazine.

The Young Marooner while it is seemingly set in South-east Asia, rather than Africa, also has the presence of pirates in common with the opening of Tarzan of the Apes, albeit they are the cause of Joco's not Tom's marooning. Of Tom and Joco, it is the latter who, though a black Jamaican, is by far the more Tarzan-like character, able to hide on the island for a long period of time before he is discovered, the only one to have a relationship with a woman, and the most adventuresome one.

So avid was the pursuit of the account of Burroughs' sailor among the apes that at least one was manufactured: "The Man Who Really Was...Tarzan," by Thomas Llewellan Jones, first published in the March 1959 issue of Man's Adventure Magazine. Here William Charles Mildin, 14th Earl of Streatham, is alledged to have lived 15 years among the apes in French Equatorial Africa after surviving the October 1868 wreck of the Antilla. A search on The Times Digital Archive 1785-1985 does not reveal any of the stories about Mildin alledged to have appeared in The Times. While José Philip Farmer also debunks the story in his Afterword to Jones' article, he himself proposes an alledged privately printed (London: Rackham, 1887) book titled Survivors by one Whitworth Russell, which contains a chapter, "The Wreck of the Antilla" outlining the similar adventures of a Lord of Streatham. A search of the British and other library catalogues does not reveal any such work.

Burroughs' source for the miscegenation story1. Early sources not available to Burroughs

While the stories of ape-human miscegenation that Altrocchitraces back (see example below) have a human female marooned, taken in, fed and housed, then impregnated by a male ape, made to bear offspring, and subjected to seeing the infants thrown in the sea or otherwise destroyed upon her escape, some versions exist that have the opposite species-gender pairing. In Hémo a 1886 French novel, Émile Dodillon's male human protagonist having killed her mate, himself mates with a she-gorilla, generating what may be a hybrid child, Hémo. In this case though, the protagonist has not been shipwrecked or otherwise compelled to live among the apes. However, here I will only discuss the female human/male ape version of the tale which Altrocchi traces back to the Italian monk Fr. Francesco Maria Guazzo and his witch-hunting manual, the Compendium Maleficarum. This saw a 1608 edition in Milan (Altrocchi, p. 254, footnote 26), but more famous is the posthumous, illustrated edition of 1626, where the tale appears in Book I, Chap. 10 (p. 60-61). A heavily cut English language edition of the Compendium Maleficarum, edited by Rev. Montague Summers, was published in 1929; the story appears there on p. 110-111.Altrocchi cites a number of later works that retell the story, but apparently missed at least a couple of earlier versions. For one, Guazzo states before the relevant passage: "Illud superat admirationem reliquorum, quod Castanneada retulit in Annalib[us] Lusitaniae." (p. 60) or "This remarkable long-ago story, Castanheda has recounted in his Annals of Portugal." In all likelihood Guazzo is citing Fernão Lopes de Castanheda's História do descobrimento e conquista da Índia pelos portugueses (1551-1561). However, Altrocchi (p. 99) states that he checked a number of 16th century Portuguese exploration accounts and did not find the story, though he doesn't mention Castanheda specifically, and he further (p. 254-255) states that the foremost Portuguese folklorist of his time, José Leite de Vasconcellos, did not know of the story — though Leite de Vasconcellos later published a version. Research is underway to establish whether or not the story appears in the close to 2000 pages of Castanheda's work

Another early 17th century Italian source, not mentioned by Altrocchi, is Strozzi Cigogna's 1605 Del Palagio de gl'Incanti & delle gran meraviglie de gli spiriti & di tutta la Natura loro (also published in Latin, 1607), a work of moral instruction, philosophy and natural history. Cigogna tells (page 211, line 23 to page 212, line 27) much the same story as Guazzo. Cigogna states: "Il Castagneda ne gl'annali de Lusitani fà indubitata fede d'un caso molto notabile." or "Castanheda in his Annals of Portugal presents as believable a strange case."

Finally, Altrocchi also missed a 16th Spanish philosophical work enhanced with strange stories, Antonio de Torquemada's Jardín de Flores Curiosas (1573). This is the earliest version of the story I have been able to confirm. Torquemada does not cite Castanheda or anyone else, but states the story as being commonly known; here it is in Ferdinando Walker's English translation of 1600.:

A vvoman in Portugale for a hainous offence by her committed, was condemned, and banished into an vninhabited Iland, one of those which they commonly call the Isles of Lagartes, whether shee was transported by a shippe that went for India, and by the way set a shoare in a Cock-bote, neere a great mountaine couered with trees and wilde bushes, like a Desert. The poore vvoman finding her selfe alone forsaken and abandoned, vvithout any hope of life, beganne to make pittifull cryes and lamentations, in commending her selfe vnto God, him to succour her in this her lamentable & solitary estate. Whiles shee was making these mournfull complaints, there discended from the mountaine a great number of Apes, which to her exceeding terror and astonishment, compassed her round about, amongst the which, there was one far greater then the rest, who standing vpon his hind legs upright, seemed in height nothing inferiour to the common sort of men: he seeing the vvoman weepe so bitterly, as one that assuredlie held her self for dead, came vnto her, shewing a cheerefull semblaunce, and flatteringly as it vvere inuiting her to followe him to the mountaines, to the which she willingly condiscending, he led her into his Caue, whether all the other Apes resorted, prouiding her such victuals as they vsed, where-with & with the water of a Spring neere therevnto, she maintained her life a certaine time, during the which, not being able to make resistance, vnlesse she would haue presently been slaine, she suffered the Ape to have vse of her body, in such sort that she grew great, and at two seuerall times was deliuered of two Sonnes, the which as she her selfe saide, and as it was by those that saw them afterwards affirmed, spake, and had the vse of reason. These little boyes, being the one of two & the other of three yeeres aged, it happened that a ship returning out of India, passing thereby, and being vnfurnished of fresh water, the Marriners hauing notice of the Fountaine which was in that Iland, and determining thereof to make tehir prouision, set them selues a shore in a Cockbote, which the apes perceauing, fled into the thickest of the mountaine, hiding themselues, wherewith the woman emboldened and determining to forsake that abhominable life, in the which she had so long time against her will continued, ranne forth, crying as loud as shee could vnto the Marriners, who perceauing her to be a woman, attended her, and carried her with them to their ship, which the Apes discouering, gathered presently to the shore, in so great a multitude, that they seemed to be a whole Army, the greater of which through the brutish loue and affection which he beare, waded so farre into the Sea after her, that hee was almost drowned, manifesting by his shrikes and howling how greeuously he took this injury done him: but seeing that it booted not, because the Marriners beganne to hoist their sailes and to depart, he returned, fetching the lesser of the two Boyes in his armes, the which, entring againe into the water, and at last, threw into the Sea, where it was presently drowned: which done he returned backe fetching the other, and bringing it to the same place, the which in like sort he held a great while aloft, as it were threatning to drowne that as hee had done the other, The Mariners moued with the Mothers compassion, and taking pitty of the seely Boy, which in cleare and perfect words cryed after her, returned back to take him, but the Ape daring not attend them, letting the Boy fall into the water, returned, and fled towards the mountaines with the rest. The Boy was drowned before the Marriners could succour him, though they vsed their greatest diligence: At their returne to the ship, the vvoman made relation vnto them of all that happened to her in manner aboue rehearsed, which hearing, with great amazement they departed thence, and at their arriuall in Portugall made report of all that they had seene or vnderstoode in this matter. The woman was taken and examined, who in each poynt confessing this fore-saide history to be truw, was condemned to be burnt aliue, as well for breaking the commaundement of her banishment, as also for the committing of a sinne so enorme, lothsome, and detestable. But Hieronimo capo de ferro, who was afterwards made Cardinall, beeing at that instant the Popes Nuncio in Portugall, considering that the one of her faults was to save her life, and the other to deliuer her selfe out of the captiuity of these brute beastes, and from a sinne so repugnant to her nature & conscience, humbly beseeched the King to pardon her, which was graunted him on condition, that shee should spende the rest of her life in a Cloyster, seruing God and repenting her former offences.This text points out an important difference between these stories and Burroughs' version of the tale he claims to have read; here (and in the Guazzo and Cigogna versions) the isolated woman is exiled to the island, whereas in some later versions she is merely shipwrecked (but suffers the same consequences).

(folio 32, line 9 to folio 33, line 16)2. Modern English sources potentially available to Burroughs

A third person cites Castanheda as the source of the tale, but this one English, and in the late 19th century. Richard Burton in a footnote to his addendum collection of Oriental tales, Supplemental Tales, states:A correspondent favours me with the following note upon the subject: — Castanheda (Annals of Portugal) relates that a woman was transporter to an island inhabited by monkeys and took up her abode in a cavern where she was visited by a huge baboon. He brought her apples and fruit and at last had connection with her, the result being two children in two to three years; but when she was being carrier off by a ship the parent monkey kissed [sic] his progeny. The woman was taken to Lisbon and imprisoned for life by the King.[...]Given the popularity of the Oriental tales of 1001 Nights when Burroughs was growing up it is not impossible that he might have come across this short version of the story.Another English language version of the story exists, albeit without the dismembering of the offspring near a body of water, but with a male human and female ape. In his Life in the Forests of the Far East (1862) Spenser St. John first informs us that:

The Dayaks tell many stories of the male orang-utans in old times carrying off their young girls, and of the latter becoming pregnant by them; but they are, perhaps, merely traditions. I have read somewhere of a huge male carrying off a Dutch girl, who was, however, immediately rescued by her father and a party of Javanese soldiers, before any injury beyond fright had occurred to her.Life in the Forests of the Far East, Vol. I, p. 22.The latter story of the Dutch girl is also related in an 1884 short story by Bénédict-Henry Révoil. While infant and adult male orang-utans will not attempt to sexually assault women, there is much anecdotal evidence and a documented case (Galdikas, 1995) of juvenile orang-utans attempting to do so.St. John, later goes on to recount a version of the story where the orang-utan is female and the human victim male:

[...] although many stories are related of the male orang-utan carrying off young Dayak maidens into the jungle, yet it is seldom that we hear of the female orang-utan running off with a man. But the Muruts of Padas tell the following narrative, which, they say, may be believed. Some years ago, one of their young men was wandering in the jungle, armed with a sumpitan, or blowpipe and a sword. He came to the banks of a pebbly stream, and being a hot day, he thought he would have a bathe. He placed his arms and clothes at the foot of a tree, and then went into the water. After a time, being sufficiently refreshed, he was returning to dress, when he perceived an enormous female ornag utan standing between him and the tree. She advanced towards him, as he stood paralyzed by surprise, and seizing him by the arm, compelled him to follow her to a branching tree and climb it up. When he reached her resting-place, consisting of boughs and branches woven into a comfortable nest, she made him enter. There he remained some months jealously watched by his strange companion, fed by her on fruits and the cabbage of the palm, and rarely permitted to touch the earth with his feet, but compelled to move from tree to tree. This life continued some time, till the female ornag-utan becoming less watchful permitted the Murat more liberty. He availed himself of it to slip down the trunk of the tree and run to the place he had formerly left his weapons. She seeing his attempted escape, followed, to be pierced, as she approached him, by a poisoned arrow. I was told if I would ascend the Padas river as far as the man's village, I might hear the story from his own lips, as he was still alive. Life in the Forests of the Far East, Vol. II, p. 156-157.However, the earliest version of the tale written in the English language is apparently that of Matthew Gregory Lewis, author of the infamous Gothic novel The Monk. Written aboard ship during the Jamaica-England voyage that would claim his life, the lengthy narrative poem The Isle of Devils. A Historical Tale, Founded on an Anecdote in the Annals of Portugal was first published separately as a small chapbook in Kingston, Jamaica,in 1827, then reprinted in certain editions of Lewis' Journal of a West India Proprietor. Specifically, The 1834 John Murray (London), and the 1999 Oxford University Press (New York) editions as Journal of a West India Proprietor Kept During a Residence in the Island of Jamaica include The Isle of Devils. The 1929 Routledge (London) edition as Journal of a West India Proprietor, 1815-1817, and a 1845 John Murray (London) edition as Journal of a Residence Among the Negroes in the West Indies do not.In The Isle of Devils an innocent virginal woman is the victim of the "Demon King" and his attendant imps which take on the form of monkeys, rather than that of a dominant ape and his lesser simian brethren. However, since in all other aspects The Isle of Devils maintains the themes of the monkey-spouse tale, it appears that the ape is merely recast in the Gothic costume of a devil. This seems to be the case since Lewis links back to Castanheda and Cicogna when he states:

This strange story was found by me in an old Italian book called "Il Palagio degli Incanti," in which it was related as a fact, and stated to be taken from the "Annals of Portugal," an historical work.While it unlikely that Burroughs would have read what is a long and rather tedious and overly melodramatic narrative poem, it is nonetheless possible that he could have been exposed to Lewis' work. As it is unlikely that Burroughs drew all of Tarzan of the Apes from a single source, one could imagine that the combination of the monkey-spouse tales and Sheridan's The Young Marooner, amongst others, could have contributed or combined to form Burroughs' remembrance of the shipwrecked sailor story he claimed to have read. One could speculate that given the tigers-in-Africa debacle, if Burroughs had drawn from Sheridan's poorly written, inconsistency-laden novel (in particular the baboons for orangs shift), he might not have been terribly keen to publicize it.

[Journal of a West India Proprietor... (London: John Murray, 1834), p. 260]Atamian, Sarkis. The Origin of Tarzan. The Mystery of Tarzan's Creation Solved. Anchorage, AK: Publication Consultants, 1997. References

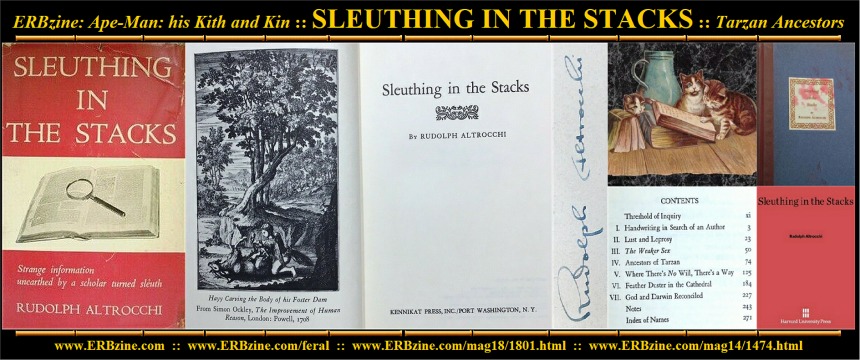

Altrocchi, Rudolph. "Ancestors of Tarzan." Sleuthing in the Stacks. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1944, 74-124.

Burton, Richard F. 1886 "Footnote No. 1, page 331" Supplemental Nights, Vol. 4, 1st ed. Benares: Kamashastra Society (16 vol. ed.)

Burton, Richard F. c. 1903 "Footnote No. 1, page 261" Supplemental Nights, Vol. 4, USA: Burton Society, nd (c. 1903). (16 vol. ed.)

Burton, Richard F. c. 1905 "Footnote No. 1, page 331" Supplemental Nights, Vol. 5, USA: Burton Club. (17 vol. ed.)

Castanheda, Fernão Lopes de. rpt 1979. História do descobrimento e conquista da Índia pelos portugueses (1551-1561). Ed. Manuel Lopes de Almeida, 9. vols. Porto, Portugal: Lello.

Cigogna, Strozzi. 1605. Del Palagio de gl'Incanti & delle gran meraviglie de gli spiriti & di tutta la Natura loro. Venice: Roberto Meglietti, 1605.

Cigogna, Strozzi. 1607. Magiae omnifariae, vel potius, Universae naturae theatrum: in quo a primis rerum principiis arcessita disputatione, universa spiritum & incantationum natura, &c. Caspar Ens, transl. Cologne: C. Butgenij.

Dodillon, Émile. 1886. Hémo. Paris: A. Lemerre, 339 p.

Eldridge, William Tillinghast. 1910. "The Monkey Man." All-Story Magazine. Sept. 1910-Dec. 1910 — 18(1): 1-15; 18(2): 232-247; 18(3): 438-451; 18(4): 648-659.

Farmer, Philip José 1974. "Afterword" Mother Was a Lovely Beast; A Feral Man Anthology, Fiction and Fact about Humans Raised by Animals. (P.J. Farmer, ed.) Radnor, PA: Chilton Book Co., 228-229.

Galdikas, Biruté Marija Filomena. 1995. Reflections of Eden: my years with the Orangutangs in Borneo. Boston: Little Brown.

Gozlan, Léon. 1856. "Les émotions de Polydore Marasquin; ou, Trois mois parmi les singes." Journal Pour Tous 1(52): p. 822 c. 2- p. 827 c. 3 (29 March); 2(53): p. 5 c. 3- p. 13 c. 1 (5 April); 2(54): p. 20 c. 3-p. 27 c. 1 (12 April); 2(55): p. 37 c. 2- p. 44 c.2 (19 April).

Gozlan, Léon. 1857. Les émotions de Polydore Marasquin. Paris: M. Lévy Fils, 291 pp.

Gozlan, Léon. 1873. "The Man Among the Monkeys; or, Ninety days in Apeland" in The Man among the monkeys, or, Ninety days in Apeland: to which are added The philosopher and his monkeys, The professor and the crocodile : and other strange stories of men and animals. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, 312 p.

Gozlan, Léon. 1888. Monkey Island; or, The Emotions of Polydore Marasquin (Charles S. Cheltham, transl.) London: Frederick Warne, 193 pp.

Gozlan, Léon. 1888. (rpt. 1890). The Emotions of Polydore Marasquin. London: Vizetelly & Co., vii + [9]-257 pp.

Guazzo, Francesco Maria. 1929. Compendium Maleficarum, collected in three books from many sources by Brother Francesco Maria Guazzo, showing iniquitous and execrable operations of witches against the human race, and the divine remedies by which they may be frustrated. Ed. Montague Summers, Trans. E.A. Ashwin, London: J. Rodker, 1929.

Guazzo, Francesco Maria. 1626. Compendium maleficarum in tres libros distinctum ex pluribus authoribus per fratrem Franciscum Mariam Guaccium Ordinis S. Ambrosij ad nemus collectum, & pluribus figuris, ac imaginibus perornatum: ex quo nefandissima, & execranda in genus humanum opera venefica, ac ad illa evitanda divina remedia conficiuntur. Mediolani: Ambrosiana typographia, 1626. (also a 1608 ed., Milan)

Kasson, John F. "Still a Wild Beast at Heart." Houdini, Tarzan and the Perfect Man. The White Male Body and the Challenge of Modernity in America. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001, 157-218.

Jones, Thomas Llewellan. 1974. "The Man who Really was Tarzan" Mother Was a Lovely Beast; A Feral Man Anthology, Fiction and Fact about Humans Raised by Animals. (P.J. Farmer, ed.) Radnor, PA: Chilton Book Co., 217-227.

Leite de Vasconcellos, J. 1963. "304. Rei e Rainha Teimosos" Contos Populares e Lendas 1 (2 vols.) Coimbra: Acta Universitatis Conimbrigensis, 562-566.

Lewis, Matthew Gregory. The Isle of Devils. A Historical Tale, Founded on an Anecdote in the Annals of Portugal. (From an unpublished Manuscript.) Kingston, Jamaica: Printed at the Courant and Advertiser Office, 1827.

Lewis, Matthew Gregory. Journal of a West India Proprietor Kept During a Residence in the Island of Jamaica, London: John Murray, 1834.

Lupoff, Richard A. "Ancestors of Tarzan" Edgar Rice Burroughs. Master of Adventure. New York: Canaveral Press, 1965, 187-202.

Porges, Irwin. "8. Tarzan of the Apes." Edgar Rice Burroughs. The Man Who Created Tarzan. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young Univ. Press, 1975, 122-142.

Prentice, Harry. 1888. The King of Apeland. The Wonderful Adventures of a Young Animal-trainer. New York: A.L. Burt, 286 p.

Prentice, Harry. 1892. Captured by Apes: or, How Philip Garland Became King of Apeland. New York: A.L. Burt, 286 p.

Révoil, Bénédict-Henry. 1884. "La Vengeance du singe" in Aventures extraordinaires sur terre et sur mer. Limoges: Eugène Ardant & Cie., 5-18. (available here

Saint-John, Spencer. 1862. Life in the Forests of the Far East 2 vols. London: Smith, Elder & Co. (rpt. Oxford Univ. Press, 1974)

Sheridan Frank (pseud. of John DeMorgan). 1908. "The Young Marooner; or, An American Robinson Crusoe." Brave and Bold No. 314 (Dec. 26. 1908). p. 1-27.

Taliaferro, John. Tarzan Forever. The Life of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Creator of Tarzan. New York: Scribners, 1999, 83-93.

Torquemada, Antonio de. 1573. Jardín de Flores Curiosas. Leyda: Pedro de Robles, y Ioan de Villanueua.

Torquemada, Antonio de. 1600. The Spanish Mandeuile of Miracles. or The Garden of Curious Flowers. VVherin are handled sundry points of Humanity, Philosophy, Diuinitie, and Geography, beautified with many strange and pleasant Histories. (Ferdinando Walker, transl.) London: Edmund Matts.

Georges Dodds is a research associate in Bioresources Engineering at McGill University in Ste. Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada. I am a long time fan and collector of pre-WW2 science-fiction and fantasy, and have written columns on early imaginative literature for WARP, the newsletter/fanzine of the Montreal Science Fiction and Fantasy Association Since 1998, I have published close to 150 book reviews at SFSite, many of reprints of older works. My favourite adventure writers include Talbot Mundy, H. Rider Haggard, and -- oh, yes -- Edgar Rice Burroughs. I am also serving as compiler-editor of a large collection of thematic precursors / contemporaries and putative research material of Burroughs' Tarzan of the Apes, tentatively titled The Incunabular Ape-Man Writings, to be published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box. This will include at minimum the texts listed here. Many texts have never been reprinted from their original magazine or book appearances; two complete novels and a novel segment have been translated from the French, and wherever possible the complete original illustrations will be included. Two rare 16th century works from which Rudolph Altrocchi ("The Ancestors of Tarzan") excerpted monkey-spouse tales will be reprinted in their entirety. Proofreading/copy-checking volunteers are welcome.

*** 1937: On this date, ERB wrote a letter commenting on the sources of his ideas for the creation of Tarzan. He was responding to a letter written to him two days earlier by Rudolph Altrocchi, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of Italian studies. ERB stated, "I believe that (the Tarzan concept) may have been originated in my interest in mythology and the story of Romulus and Remus. I also recall having read many years ago the story of a sailor who was shipwrecked on the coast of Africa and who was adopted and consorted with great apes to such an extent that when he was rescued a she-ape followed him into the surf and threw a baby after him. Then, of course, I read Kipling: so that it probably was a compilation of all three of these...."

From our ERB EVENTS Site

https://www.erbzine.com/mag63/6322.html#MARCH31

Altrocchi was doing research for a book, "Sleuthing in the Stacks," which would be published six years later in 1943. The book contains chapters on a wide range of literary achievements of the past with Altrocchi's investigations and ideas about books and characters, written with his hope that the volume would be "a jolly, bookish escape."

Based on his correspondance with Edgar Rice Burroughs, Rudolph Altrocchi in his "Ancestors of Tarzan" stated:

There was another source for Tarzan. Somewhere, perhaps in some magazine and certainly before 1912, Mr. Burroughs read a story about a sailor who, as the only survivor of a shipwreck, landed on the coast of Africa. There he tried to make the best of a difficult situation, à la Robinson Crusoe. During this forced sojourn in the jungle, a she-ape, which he had tamed, became so enamored of him that when he was finally rescued, she followed him into the surf and hurled her baby after him. This modern story I have been unable to find. (Altrocchi, p. 95)

Two issues devolve from this and the theme of Tarzan being raised by apes: (i) the story of survival of a shipwrecked sailor among friendly apes, (ii) the miscegenation of human with ape, and the consequences of the "divorce." With regard to the second question I am preparing a folklore paper which expands significantly on Altrocchi's search in these matters, particularly with respect to the 16th century origins of the tale. This will eventually be submitted the a folklore journal Estudos de Literatura Oral. However, I propose two 19th century English sources where Burroughs might have come across the story. ~ From Our Ape-Man: His Kith and Kin Project by Georges T. Dodds - McGill University

Altrocchi and other influences in ERBzine

http://www.erbzine.com/mag14/1474.html

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin by Georges Dodds:

http://www.ERBzine.com/feral

Hundreds of related text ~ Thousands of words and photos

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/1801.html

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/indexape.html

More feral kids:

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/1899.html

The Origin of Tarzan: The Mystery of Tarzan's Creation Solved

by Sarkis Atamian with Foreword by George T. McWhorter

http://www.erbzine.com/mag11/1151.html

BACK TO THE OPENING KITH AND KIN PAGES

www.erbzine.com/mag18/1801.html

www.ERBzine.com/feral

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2006/2014/2020 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.