Rex Maxon Arrives

Rex Hayden Maxon (1892-1973), son of a house painter, was

born in Lincoln, Nebraska on March 24, 1892. When Rex was still a boy,

his brother, Paul, and well-known artist-to-be, Clare Briggs, actually

studied cartooning together. The Maxon family moved to Webster Groves,

a suburb of St. Louis, Missouri. He spent much of his youth sketching the

old river steamers on the Mississippi waterfront but his parents thought

that one artist in the family was enough and encouraged him to become an

electrical engineer. Rex stuck to his dream, however, and obtained a summer

job during his high school years painting the river steamboats for the

Government. He enrolled for private art lessons from J. LeBrun Jenkins

and studied at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts. He later joined the staff

of the St. Louis Republic newspaper. After a short period in Chicago, where

he studied art at the Art Students League, worked as an idea man for a

small ad ajency and did advertising art for the Lord and Thomas Agency.

His first job there was drawing shoes for three dollars a week. Inspired

by St. Louis Republic colleague Hazel Carter who had moved to New York

to work for Evening World paper, he moved east in 1917. Here he lived

with Arthur Button in a small studio on 37th Street where they nearly starved

to death. He carved out a meagre existence selling theatrical and semi-comic

newspaper features to the Evening Mail and later the New York Globe. Rex

and Hazel jarried in 1920 and they worked together producing Carter-Maxon

features for the New York Glove until it folded. They also did advertising

and newspaper serial illustrations using real models for accuracy in their

work. During this time Joseph Neebe of Famous Books and Plays, and Max

Elser of Metropolitan National Syndicate, impressed with Maxon's experience

in working with the human figure, contacted him to try out to carry on

the daily Tarzan strip that had been started by Harold Foster. Foster had

adapted Burroughs first Tarzan novel, Tarzan of the Apes in early

1929.

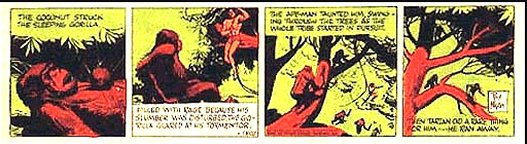

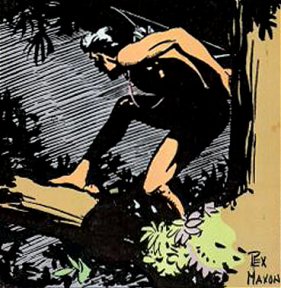

Rex Maxon started the daily black and white Tarzan strip

on June 10, 1929. Palmer, a writer in Cleveland, plotted out The Return

of Tarzan and Rex did the first ten weeks for free. The strip was successful

and was sold to United Features Syndicate. Maxon continued to draw the

series, almost continuously, for the next 18 years -- a total of 5,200

strips. The adaptations were written by George Carlin and later by Don

Garden. Rex took over the scripting during WWII, debuting with the a story

involving bats flying out of a cave.

On March 15, 1931, the Tarzan colour Sunday page

was inaugurated and Maxon took on this assignment as well. Unfortunately

Foster was a hard act to follow. Maxon's inadequacies as an illustrator

and storyteller, which may have been acceptable on a black-and-white daily

strip, were magnified by the larger colour panels. Many thought him an

odd choice as he lacked his predecessor's skill in figure drawing, composition,

and several other abilities essential for the drawing of a jungle adventure

strip. Edgar Rice Burroughs, especially, disliked Maxon's approach and

complained frequently to the syndicate about the strip's art and story

lines. He even suggested that Maxon be given photos of animals so he could

learn to draw them correctly. Maxon, however, was kept on, possibly because

he worked cheap.

In response to Burroughs' complaints, the syndicate brought

back Harold Foster to take over the Tarzan colour Sunday pages -- giving

Maxon more time to concentrate on the daily strips. This was the start

of a very successful run that would stretch from September 27, 1931 through

May 2, 1937. Foster then went on to even greater success with his own strip,

Prince

Valiant.

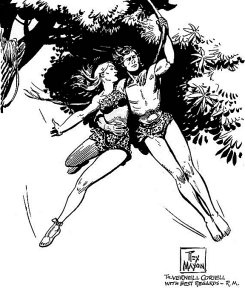

Between 1929 and 1947 Rex Maxon illustrated all but five

of the 27 Tarzan story-strips that were published in newspapers. He continued

the strip with original material when the story-strips finally caught up

with ERB's output of novels. The Maxon image of Tarzan changed over the

years. His original version of the apeman seemed to draw from James Pierce,

as he appeared in Tarzan and the Golden Lion. He illustrated him as a handsome

figure with short hair and a shoulder-draped leopard skin. Through the

years, however, the progression of Tarzan's appearance reflected the public's

changing tastes. A clever example of the change in the apeman is evident

in Maxon's illustrations for the Tarzan the Untamed storyline. As

the strip progressed his hair was shown a little longer each day and he

became more savage looking. The draped leopard skin was replaced by a loin

cloth. By the end of the story Tarzan had been modernized into the more

graceful figure that would be used from then on except for a period in

1936 and 1937. Maxon quit over a pay dispute and William Juhre took over

the strip until it started losing money and Rex was asked to return.

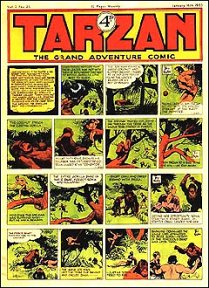

On August 28, 1939, the daily strip dropped its original

four-panel format with text below and adopted the format still in use today.

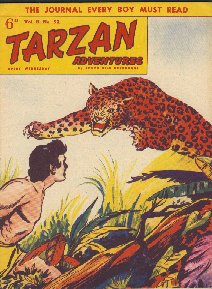

Most of these numbered daily strips have been reprinted in the English

comic,

Tarzan Adventures (This numbering started with matrix # 0001

and ran to #9999 by Russ Manning -- and ended with RM0308 / 10308)

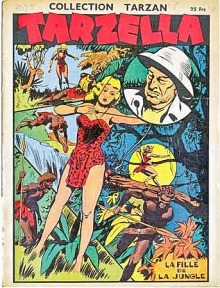

Many of Maxon's Tarzan drawings have found their way into

book form. Almost all of his early works were reprinted in the Whitman

Big-Little and Better-Little Books, and some found their way into foreign

hard covers such as TARZAN ET LES JOYAUX D'OPAR and TARZAN ET LA VILLE

D'IVOIRE, Canadian editions published in French..

After leaving the Tarzan comic strip in 1947, Rex Maxon worked

as a free lancer, mainly illustrating cowboy stories. His work can be found

in Young Hawk, the secondary strip of Dell's Lone Ranger comicbook, throughout

the 1950s. In 1954 Rex Maxon drew all the interior art for the first issue

of Dell's

Turok, Son of Stone. He evidently cooperated with editor Matt

Murphy in creating the characters of Turok and Andar, and in formulating

the prehistoric, Doylesque "Lost Word" that the Indian braves discover.

After his contribution to that first issue, Maxon's appearances in Turok

were sporatic. Most of the strips, during the comic's first years, were

drawn by unsigned artists like Bob Correa, Ray Bailey, Bob Fujitani, and

perhaps also Frank Bolle and Samuel J. Glanzman. Rex Maxon generally contributed

a four-page "educational" filler strip on prehistoric beasts, entitled

"Young Earth," but his work on the Turok strip itself was rarely published.

After Alberto Giolitti took over the Turok comic illustration

duties in 1962, Rex Maxon occasionally supplemented the Italian artist's

efforts by drawing the magazine's main story. A notable example may

be seen in the issue for Sept.-Nov.,

1962, where Maxon drew all the interior art, including the Young Earth

strip. Whether this work was a contemporary contribution or a restrospective

inclusion of earlier, previously unpublished Maxon art remains unclear.

Maxon retired from drawing comics a few years prior to his death in 1973,

but his work continued to appear in Turok throughout the late 1960s and

into early 1970s. He and Hazel moved to London in 1969 where he did water

colour painting and worked on portraits. His final years were spent with

Hazel and their daughter, Jeanne, about 45 miles from New York, in Rockland

County on the Hudson river.

Rex Maxon relaxes on the bridge leading to his sister's

cabin

in the South St.Urain Canyon in Colorado.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()