The First and Only Weekly Online Fanzine Devoted to the Life and Works of Edgar Rice Burroughs Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive Volume 0527 |

|

The First and Only Weekly Online Fanzine Devoted to the Life and Works of Edgar Rice Burroughs Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive Volume 0527 |

|

Part I

by Alva Johnston

The Saturday Evening Post

July 29, 1939

Everybody sooner or later turns out ot be a writer. Get deep enough into anybody's confidence, and you find that he has manuscripts. Psychoanalysts build a false science on the theory that millions of people are maladjusted lovers; a better knowledge of the world would teach that they are maladjusted writers.David Binney Putnam launched himself on a serious literary career by wearing coveralls, growing a beard and setting out to get the life stories of derelicts; the first derelict he met was a writer who took out a notebook and insisted on having young Putnam's life story.

All this shows that, as Ed Howe put it, the people are smart. They are on the right trail. Writing is the shortest cut to affluence except inheriting big money. Today is the harvest time for writers, and tomorrow's prospect is still better. A sure-hit writer can get $5000 a week and upwards in Hollywood. A good radio-script man or woman is worth four figures a week. Magazine editors and book publishers go out in posses after any promising writer. Writing is the royal road to statesmanship; there is an enormous demand on the part of public men in Washington and elsewhere for artists in the oration-writing department of belles-lettres. Television holds a promise of becoming a writer's paradise; if it is a success it will require legions of writers to feed the television studios with scripts.

The paradox of the literary situation is that, while everybody is a writer, there is a shortage of writers for the thousand-a-week spots and the five-thousand-a-week spots. According to Pandro Berman, head of the RKO picture studio, Hollywood can't get one tenth of the good writers it needs. His solution of the problems is for the universities to stop concentrating on the second-rate professions, which are already overcrowded , and to devote themselves to turning out big-money master writers, who are needed by the thousands. Law, medicine, engineering and the sciences have proved themselves to be excellent stopgaps and steppingstones for writers, but the demand of the time is for direct literary training which will enable young men and women to assume the thousand-a-week burdens immediately on graduation.The main difficulty with Berman's suggestion is that of organizing the courses. Nobody seems to have worked out a satisfactory method of training writers to write. Colleges are good on punctuation marks, but not on what to put between them. Famous writers seem to have left few hints that are useful to beginners. Ring Lardner said it was a matter of selecting pencils of the right colors. Anthony Trollope said it was a matter of attaching the writer's pants to the chair with beeswax. Goethe attributed his output to a chair in which it was impossible to get into a restful position. In the vast literature about Dr. Samuel Johnson, only one practical rule of writing is to be found, and Doctor Johnson had that from an old schoolmaster; the rule being that, if you think any sentence you write is particularly good, strike it out. Dickens picked up his technique by accident. As a Parliamentary shorthand reporter during the decadence of parliamentary oratory, he learned the comic effect of presenting trivialities in ornate and sounding prose.

Tests of Greatness

The subject has to be simplified before the universities can turn out prose masters on belt conveyors. A new approach to the problem would be to take the greatest living writer and make a thorough analysis of the factors which caused his greatness. Because of differences of opinion as to who is the greatest living writer, it is necessary to adopt arbitrary tests to identify him.These tests are:

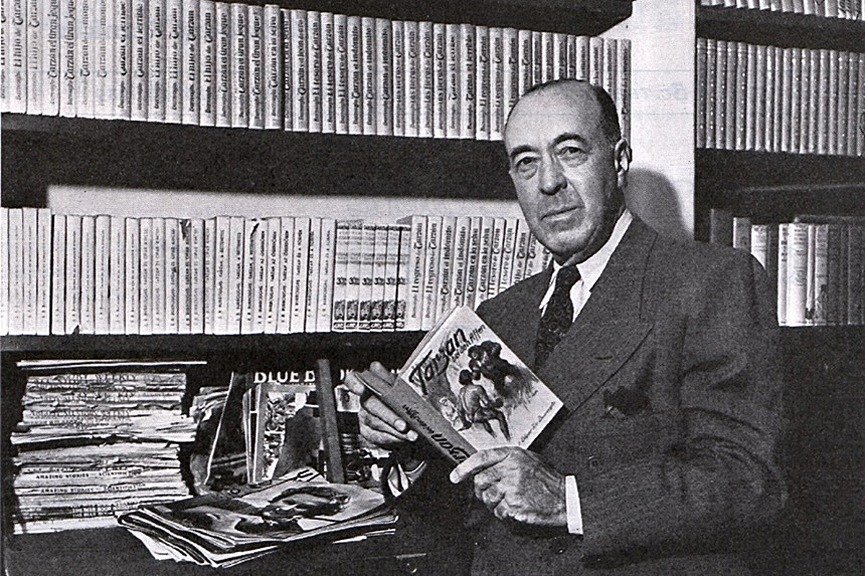

Judged by these tests, Edgar Rice Burroughs is first and the rest nowhere.1. The size of the writer's public. 2. His success in establishing a character in the consciousness of the world. 3. The probability of his being read by posterity. No other literary creation of this century has a following like Tarzan. Another character with a world-wide public is Mickey Mouse, but he belongs to a different art. The only other recent works of imagination in this class are Charlie McCarthy and The Lone Ranger, but their vogue is confined to the English-speaking peoples and they are still novelties rather than assured immortals.

Twenty-five million copies of the Tarzan books have been sold. Tarzan has established his durability; the first book on the ape boy came out a quarter of a century ago, and he is today more popular than ever. A writer's foreign following has been described as a contemporary posterity; Tarzan books have been translated into fifty-six languages and dialects. Hundreds of baseball players, football players, wrestlers, fighters and other athletes are nicknamed Tarzan. Extra-large schoolboys are called Tarzan in admiration, and undersized ones are called Tarzan in derision. Sherlock Holmes, Peter Pan, Pollyanna and Babbitt are perhaps the only literary creations of the last fifty years whose names are rooted in the English language as strongly as Tarzan; and Tarzan is a household word on every continent and on the larger islands from Iceland to Java.

Tarzan is a pillar of the American fiscal system. Through his author, his motion-picture company, his cartoon-strip syndicate, his radio sponsors and his various other concessionaires, the African ape boy contributes enough in taxes to pay the salaries of most of the United States senators.

What Makes Him ClickBurroughs is clearly the man to tell the 130,000,000 American writers how to write. His life story ought to be the supreme textbook. The main rules for literary training that can be gathered from the experiences of Burroughs are:

Burroughs had been an ill-paid employee and an unsuccessful small businessman for fifteen years before he wrote a word of fiction. The great difficulty in basing a college training on his rules is that of compressing into four years all the dullness, wretchedness and futility which it took Burroughs fifteen years to assimilate.1. Be a disappointed man 2. Achieve no success at anything you touch. 3. Lead an unbearably drab and uninteresting life. 4. Hate civilization. 5. Learn no grammar. 6. Read little. 7. Write nothing. 8. Have an ordinary mind and commonplace tastes, approximating those of the great reading public. 9. Avoid subjects that you know about.

King of the Pot-and-Pan TradeHaving no experience with salesmanship beyond that of being repulsed by housewives when he tried to sell sets of Stoddard's Lectures, Burroughs wrote a correspondence course on salesmanship. After studying by correspondence for a few weeks, his students were to be graduated into field work. Small stocks of aluminum pots and pans were sent to them with instructions to sell them from door to door and remit the money to the home office.

Burroughs and his partner thought there were millions in it. They regarded themselves as aluminum kings about to corner the pot-and-pan trade with the help of peddlers who would pay tuition fees for the privilege of peddling. But the students all quit when they got to the field-work stage. Some failed to send back either the money or the pots and pans.

The Burroughs family had been rich when Edgar was a boy, but had lost its money. His allowance at prep school had been $150 a month. During his entire business career he never earned as much as his pre-school allowance. Twice he was compelled to pawn his family heirlooms in order to buy food for his wife and children. His failure as a businessman was so complete that he was reduced to earning a living by writing hints on how to become a successful businessman.

The businessman's bible three decades ago was System, the Magazine of Efficiency. It was a pioneer in introducing charts and graphs. Many businessmen worshiped charts and graphs as religious symbols. It was their belief that, if they stared long enough at these mystic curves and angles, red ink would turn into black.

A new department was introduced by the magazine. On payment of fifty dollars a year, a businessman could write to the magazine as often as he liked, and receive detailed advice on his business problems. Burroughs was hired to give the detailed advice. There was also a detailed advice department for bankers, which was handled by a youth of twenty-one years. Burroughs sat at his desk from morning until night, writing counsel to merchant princes and captains. He used words that rumbled with portentous business wisdom, but were too vague to enable any industrial baron to act on them. Burroughs had a conscience, and it was always his fear that, if his advice ever became understandable, it would land his clients in the bankruptcy courts. With his letters he would enclose some of the awe-inspiring hieroglyphics now known as "barometrics"

Burroughs' advice never brought a complaint, and he may have been as good as anybody else in this field. Nothing is definitely known on the subject today except that the more the charts and graphs flourish, the faster business decays.

Burroughs' first contact with literature came in 1911 through his connection with Alcola, a cure for alcoholism. Alcola cured alcoholism all right, but the Federal Pure Food and Drug people took the position that there were worse things than alcoholism, and forbade the sale of Alcola.

One of Burroughs' duties in the Alcola firm was that of putting advertisements in the pulp fiction magazines. He bought the magazines in order to make sure that his ads were printed. He detested fiction, but when he looked at the ads some of the reading matter entered his field of vision. His reaction was approximately that of Dean Swift, who, under similar circumstances, exclaimed, "No man alive ever writ such damned stuff."

His next thought was that, if this was literature, any man could be a man of letters if he would abandon his mind to it. He wrote a novel. Thomas Newell Metcalf, editor of the All-Story Magazine, accepted it and sent Burroughs a check for $400. It was published as a serial in the All-Story in 1912, under the title of Under the Moons of Mars.

Burroughs saw the folly of research. He had located his first novel on Mars because nobody knew the local color of that planet or the psychology of the Martians, and nobody could check up on him. A similar motive influenced him partly in writing his first Tarzan book, Tarzan of the Apes. He created a new race of apes, bigger than gorillas, and placed them in an unknown part of Africa. He knew that nobody could trip him up on the psychology, customs and language of his own private anthropoids.

For African local color he read Stanley's In Darkest Africa. He got his flora all right, but he made a blunder in his fauna. One of his important characters was Sabor, the tiger. There are no tigers in Africa. Letters from readers were printed in All-Story on this point. A man in Johannesburg confounded the entries, however, by writing that everybody in Africa referred to leopards as tigers. Nevertheless, Burroughs later changed Sabor to a lioness. He got a check for $700 from All-Story for Tarzan of the Apes.He was too poverty-stricken to pay for any of the tired businessman's relaxations, but he hit upon a free method of making himself feel better. When he went to bed he would lie awake, telling himself stories. His dislike of civilization caused him frequently to pick localities in distant parts of the solar system. Every night he had his one crowded hour of glorious life. Creating noble characters and diabolical monsters, he made them fight in cockpits in the center of the earth or in distant astronomical regions. The duller the day at the office the weirder his nightly adventures. His waking nightmares became long-drawn-out action serials.

The Delirium Road to Success

Psychiatrists consider these reverie addicts as borderline cases. If Burroughs' family had known of his mental state, they would have called in a medical man, who would have probably insisted on having his teeth out, according to the fashionable method of treating such patients in 1911. Twenty years later, Burroughs would have been advised to save up his money for a few years and go to a psychoanalyst, who would have cured him of an incipient $10,000,000 affliction. A raise of twenty-five dollars a month in 1911, according to Burroughs' estimate, would have made him happy and caused him to put in nights of sound, refreshing slumber, instead of constructing penny-dreadful deliriums for himself.

Burroughs had given away serials to himself for five years or more before he learned that he could sell them. He had become a master of the slaughterhouse branches of fiction. It is clear from reading the Tarzan and other Burroughs books that he devoted little of his twilight sleep to tea-table and boy-meets-girl imbroglios.

Five years of dark and bloody mysteries gave his pen a high professionalism in pryamiding climaxes and piling up horror; but he was an awkward novice when the structure of his novel required him to introduce scenes of society life or hearts-and-flowers passages. Burroughs is great when Tarzan has a half nelson on a lion or a gorilla, but he has no talent for drawing-room hubble-bubble or boudoir hanky-panky. There is a trace of Homer in him, but not any Noel Coward.

In Tarzan of the Apes the reader can put his finger on the passages where Burroughs is the dream-disciplined artist and on the passages where he is the self-conscious amateur. He wanted to endow his ape-reared infant with a magnificent heredity. He was under the impression that the way to have a glorious moral, mental and physical inheritance was to be a scion of the British aristocracy. So Tarzan's parents were Lord and Lady Greystoke, the flower of the old nobility. Burroughs created them out of condescending sawdust.

One brilliant passage is that in which the half-grown Tarzan identifies himself as the being who is reflected in a pool of water. Tarzan had already had reason to suspect that he was not a true born ape. Gazing at himself in the waters, he discovers what a poor relation of the higher anthropoids he really is. Burroughs is in a high literary vein when he describes the boy's chagrin in comparing his parody of a countenance with the pretentious physiognomies of his playmates. Instead of nostrils that spread half across his face, he had a despicable imitation of an organ of smell. He had trifling bits of ivory where competent tusks should have been. Self-pity overwhelmed him when he discovered that his eyes were an insipid gray instead of being big, black and bloodshot. On realizing that he was hairless like a snake, he plastered himself from head to foot with mud.

Tarzan had already suspected that he was not a true ape, because he had discovered in a deserted cabin a number of kindergarten books with pictures of animals. He had begun to fear that he resembled the apes less than he resembled another animal, whose pictures was always printed with what appeared to be three little bugs -- B, O and Y.

Using these three bugs as a clue, Tarzan works out the secret of all the twenty-six bugs in the alphabet. He learns how to pronounce it. Burroughs' handling of Tarzan's self-education is better than the cipher sequences in The Gold Bug or The Dancing Men.Tarzan's discovery that he is a member of the human species later lands him in a beautiful ethical dilemma. Having killed an African tribesman, Tarzan is about to help himself. Certain doubts assail him. His bringing up had taught him that eating a member of one's own species was not done. He has eaten raw gorilla, but the gorilla does not belong to his set. Tarzan now knows himself to be a man, and he recognizes the dead African as a man. On the other hand, Tarzan is hungry, and his political sympathies are all with the apes. It is a pretty case of conscience, and Burroughs does justice to it. In the end Tarzan takes the high ethical stand and never refreshes himself with an African.

![]()

CONTINUED IN

TARZAN

OR

How To Become A Great Writer

Part II

www.erbzine.com/mag5/0528.html

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2004/2021 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.