In spite of the idyllic setting that my life now took

place in, I could not forget that Savjoda was out there and planning the

conquest of Barsoom.

Two more times, we witnessed the opening of roads to

the surface world. Both openings were brief, too brief to allow a major

invasion of the surface, but certainly things were happening. The most

important thing was that these openings were reminders that Savjoda's plans

moved forward while we did nothing.

In Dhaimira, as I have stated before, there are virtually

no metals, yet somehow, we had to make the tools that would allow us to

either escape this world or catch up with Savjoda. Barsoom is far older

than Earth and the ways of the primitive much farther behind the Barsoomians

than the inhabitants of Earth. It is for that reason that Tamla barely

comprehended the concept of stone tools.

On Earth, even as recently as the reign of the Kalkars,

men had chipped knives and axes out of flint, while Barsoom had lived in

the age of steel for millions of years. Tamla reacted to my inept efforts

of making tools from stone as if I had performed a magic trick.

It took me a few tries to make a useable axe-head,

but I got quite a bit of practice due to the fact that they wore out quite

quickly. The task of constructing a sturdy boat fell mostly to myself.

Having been raised on the dry sea bottoms of Barsoom, the young princess

understood little of the theory behind watercraft.

Over time, a seaworthy craft took shape. I cooked tree

sap to pitch the hull and carved pegs to hold the boards together. The

joined and pitched boards were then covered with animal hide as was a roofed

enclosure inside the craft itself. I made a sail from large leaves sewn

together. Tamla and I sailed on a few short excursions from our camp to

survey the coast and work out problems with the boat's construction.

In spite of the fact that Keltrolna was quite small

compared to any of Earth s continents, it was still of impressive size

and variety. We spent some time exploring all along the western coast where

we saw many wonders.

We had few really good choices for how we should proceed.

Tamla thought that we should head into the South Polar region where she

thought there might some sort of route into the Sea of Omean and from there

we might reach the Sea of Korus. I, on the other hand thought that the

course most likely to succeed would be to make for Savjoda s capital and

wait to see if we could get back when he next opens a road.

We devoted ourselves to the study of what might be

called Dhaimiran "astronomy." We had to create a clear map of our world

but we were subject to the sorts of limitations that were usually faced

by astronomers, that is the vicissitudes of the weather. We also had no

telescope although that was not too much of a handicap. Dhaimira's diameter

is approximately three thousand miles making it only slightly larger than

Vah-Nah. The shell of Barsoom was rather thicker by proportion than that

of Earth which encloses Pellucidar. The result of this was that the atmosphere

was considerably easier to see through than that of Pellucidar. On the

other hand, the sun effectively blanked out a larger portion of the sky

than did the sun of Pellucidar. Luckily for us, our camp was located very

near the equator and we were able to see both polar regions. We discovered

two things. The first was that we could not tell with any certainty the

direction of the planet s rotation, therefore, we remained unsure as to

which pole was which. The second of which was the presence of land masses

located over both poles making a direct sea passage to the surface unlikely.

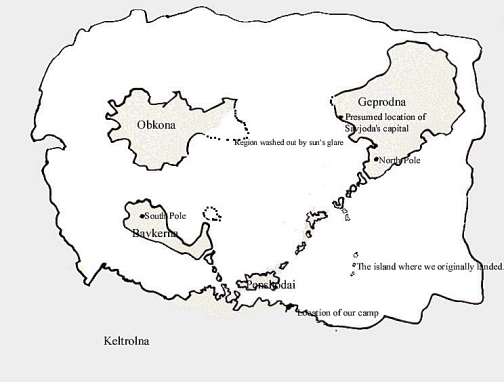

This is a copy made from the first map we made in

western Keltrolna.

The land of Keltrolna can be seen to encircle all

the other lands and waters, for this is how it appeared from our vantage.

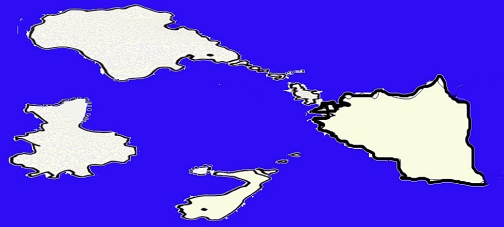

This is the best surmise I could make of the actual

shape of the lands of Dhaimira

if they were to be laid out flat. Geprodna is at the

top of the map and Keltrolna is on the right hand side.

We reluctantly determined that seeking out Savjoda

offered us the best chance of escape. We had, through our geographical

explorations, found a place that we believed to be Savjoda's base of operations.

It was almost on the exact opposite side of the world from us. This made

me wonder why we entered Dhaimira where we did. Were there other plans

for Tamla aside from those stated by the jomads?

I contrived a clock of sorts, really more like an ancient

sand glass. It dribbled a stream of sand from one container to another

over a period of approximately 4000 resting heartbeats. I arbitrarily decided

to call a period where we reversed the containers 20 times a day and 30

of those periods a month. Both Tamla and I felt much better with a method

of time-keeping, although now that we had one, we became aware of how fast

the time was going by.

It took us half a month to prepare supplies for our

voyage. They consisted of dried meats and wild vegetables and many skins

filled with spring water.

The darmayoks had left us a vial of their water purification

chemical, but we felt it was best to regard that as emergency stores. Also,

the water skins made good ballast and helped keep the boat from rocking

too far in one direction or the other.

We reluctantly determined that seeking out Savjoda

offered us the best chance of escape. We had, through our geographical

explorations found a place that we believed to be Savjoda s base of operations.

It was almost on the exact opposite side of the world from us. This made

me wonder why we entered Dhaimira where we did. Were there other plans

for Tamla aside from those stated by the jomads?

I contrived a clock of sorts, really more like an ancient

sand glass. It dribbled a stream of sand from one container to another

over a period of approximately 4000 resting heartbeats. I arbitrarily decided

to call a period where we reversed the containers twenty times a "day"

and thirty of those periods a "month". Both Tamla and I felt much better

with a method of time-keeping, although now that we had one, we became

aware of how fast the time was going by.

It took us half a month to prepare supplies for our

voyage. They consisted of dried meats and wild vegetables and many skins

filled with spring water.

The darmayoks had left us a vial of their water purification

chemical, but we felt it was best to regard that as emergency stores. Also,

the water skins made good ballast and helped keep the boat from rocking

too far in one direction or the other.

We set out on a calm sea using only the map we had

prepared for navigation. Frequent overcast weather made our progress slow

and before more than five days had passed, we were forced to land at the

first island we saw to wait until we could get our bearings.

The island was lushly forested with the leafy cup trees,

not unlike the one we made our escape from the jomads in, each with its

own little pond. There was ample hunting and forage for us to eat well

and replenish stocks as we needed.

Beyond the forest that lined the coast was a savanna

interrupted by occasional trees and watering holes. The ground cover was

both Earthly grasses as well as Barsoomian yellow moss, thus we were not

overly surprised to see that the land was shared by elephants and wildebeest

as well as wild thoats and zitidars. Here were also various beasts, which

were of obviously Dhaimiran origin, some of which were too fleet of foot

for us to get a clear look at. We also spotted lions and calots which convinced

us that it would be better for us to return to the coastal forest.

After some time, we determined that we were on a large

island that Tamla identified as Penshodai. This island sat at one end of

an archipelago that reached all the way to Geprodna.

If we stayed in the region of these islands for our

journey, we would always be near land and in shallow, warm waters, but

we would also be more exposed to discovery by Savjoda s jomad minions.

Even so, the limitations of our boat and our dependence on being able to

see our destination militated against attempting a long voyage on the open

ocean. Thus it was that we agreed to make our journey along the line of

islands.

![]()

![]()

![]()