Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 10,000 Web Pages in Archive

Volume 2803

Presents

Ed Burroughs swallowed dryly and stared hard at the four cards laying on the scarred wood of the table at which he sat.

TARZAN: THE SUCCESS OF FAILURE

by

Russell Madden

A shorter version of this article first appeared in Burroughs Bulletin No. 44 ~ Fall, 2000

The complete article is featured in Russell Madden's Website

at: www.russellmadden.com/Success_of_Failure.html

Bit by bit he had watched the forty dollars he had brought into this stud poker game migrate into the piles of the other players. His hopes of swelling his stake into a few hundred dollars for the trip to Parma, Idaho, were drifting away as surely as the wreathes of smoke floating in the stuffy air of the saloon.

What would Mrs. Burroughs say if he returned, flat broke, to their rented room?

Frowning, Ed lifted the corner of his hole card. Suspiciously, he looked at the one-eyed tinhorn who had done his best to rattle him all night. The man was surely crazy. Just as surely he had won far too many hands. Laying the side of his head with his good eye on the table top, Ed's rival peeked at his own hole card...and that of anyone else foolish enough to raise their hidden card too high.

"Come on, Ed," the man to his right said, smiling smugly. "Either see his bet or fold."

Ed wiped the sweat from his brow with his bare arm. The tinhorn's cards showing could not beat his. But if that fool had the card he needed...

Inhaling a ragged breath, Ed shoved the last of his coins into the jumbled pile that constituted the pot. "All right. I see him." Defiantly, he glanced up. "Let's see what you've got."

"Read 'em and weep, Ed." With a flourish, the tinhorn straightened and flipped over the final card.

With a sinking feeling mixed of dread, anger, and fear, Ed saw the tinhorn's inside straight suddenly fill and snatch away the promise of his own concealed three-of-a-kind.

The midnight walk back to the company of his wife, Emma, and his collie dog, Rajah, stretched interminably long and cold. Once again he had risked it all...and lost. Here it was, 1903, barely into a brand-new and promising century, and here he was, nearing thirty and still a failure. When would he ever learn? When, indeed?

As a college instructor, I have to deal with all levels of success and failure. Even when not assigning grades, I must still evaluate the work of my students and determine how well they have done in meeting the criteria established for their assignments. Of course, when the time does roll around for writing down their final letter grades, I must decide who will receive "A's"...and who will have to stare down at that unwanted "F" when they open their semester grade reports.

Deciding on who will sit at both the top and the bottom of the grade scale is difficult for me. In this era of "grade inflation," I want students to know that in my classes, at least, an "A" means something: it is a sign of superior effort and/or skill in mastering the subject matter.

The men who try to do something and fail are infinitely better

than those who try to do nothing and succeed:

~ Lloyd JonesMarking down an "F" can be difficult for other reasons. Some students try but never quite "get it." Others seem never to have experienced much success in school. They engage in self-fulfilling behaviors such as not handing in assignments on time or withdrawing from class participation and thereby ensuring that they will, in fact, receive the very grades they mentally predicted for themselves. Still, troublesome though it is for me, I write down the grade which I believe they have earned in the perhaps vain hope that the failing student will learn from the experience.

There are many avenues for discovering the lesson that failure has a purpose; that it can be viewed as an opportunity and not a punishment. One way to learn about the value of failure is through personal experience. Another road to that realization is to follow the paths others have taken, that is, to examine the examples of famous or not-so-famous people and the failures -- and subsequent successes -- which they faced.

Role Model

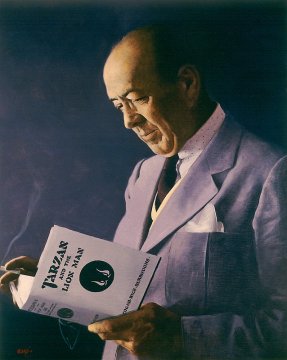

One man who provided such a role model for me was someone I never met but who still had a profound influence on my life as a teenager and young adult. While Edgar Rice Burroughs may not be a household name, that of his most famous creation is. For Edgar Rice Burroughs -- known to his friends and family as Ed -- is the man who brought life to Tarzan of the Apes.

Though ERB (as he was also known) eventually achieved fame and fortune, for the first thirty-five years of his existence, life appeared to be one long slide into oblivion broken only by all-too-brief flashes of hope and pleasure. For this man, nearly everything he touched turned to lead, not gold. Little did he dream during those periods of failure that he would one day spin yarns of a jungle man named Tarzan of the Apes through over two dozen novels. The millions of dollars and the millions of fans he would earn did not exist for the young ERB as even a glimmer in his mind's eye when he began his quest for wealth.

After a wild and rambunctious childhood, Ed knew his father, George, wondered if his youngest surviving son would ever amount to anything. In fact, Ed started down the road of adult life with what at the time seemed to be a devastating failure. Born in Chicago on September 1, 1875, as a teenager Ed attended the Michigan Military Academy in Orchard Lake. It was George's hope that this school would provide the discipline which Ed seemed unable to cultivate within himself.

Rebellious Student

A mediocre student at best, Ed chafed under the rules and regulations of what was rumored in polite company to be a reform school for problem children of the well-to-do. Promoted and busted to ranks more than once for infractions of the rules, Ed still managed to gain popularity among the other plebes due to his outgoing nature. His skill with horses as well as his quick wit earned him the respect of his instructors. Though he reveled in the physical and the dangerous, he also had a flair for the artistic. His cartoons, humorous poems, and drawings enlivened many of the student publications at the Academy.

Ed relished the military life and planned a career in the arena of cavalry and cannons. Yet despite his affection for things martial, he deserted due to what he perceived as the hardships of training. Only an indulgent father and an understanding commandant enabled him to make amends and continue on to graduation. A subsequent hoax in which he and another student planned to fake a gun duel to the death almost short-circuited even this second chance.

Somehow Ed managed to reach the end of his academic career. With the aid of his father's influential friends, he was afforded a chance in 1895 to attend West Point. An officer's career with its promise of excitement, adventure, and honor would surely follow. The actual result reflected all-too-readily the theme of failure with which Ed became sickeningly familiar during the next fifteen years. A hundred and eighteen young men took the entrance examination. As Ed put it later, "Only fourteen of them passed, I being among the one hundred and four."

Chagrined though both he and his father were at this setback, Ed's career as a soldier was far from over. That autumn, he managed to gain a position as an instructor back at Orchard Lake. Though he knew nothing about the subject, he was assigned to teach geology. In a scenario familiar to many first-time educators, he managed to make it through the course by studying the material thoroughly and keeping one step ahead of his less industrious students.

A combination of loneliness and restlessness spelled a quick end to his association with the Academy. Though he was underage, Ed convinced his father to provide his consent for his son to join the Army.

The Seventh Cavalry

With visions of derring-do dancing in his head, Ed succumbed to a fit of youthful passion and requested that he be sent to the worst posting in the country. In such an environment, he thought, he could prove his bravery and skills and be granted the officer's commission he had been denied by the failure at West Point.

In 1896, broke again after some foolish purchases en route, Ed managed to reach his posting at Fort Grant, Arizona. The unit he joined was the Seventh Cavalry, the ill-fated group which General Custer led at the Little Big Horn to ignominious defeat and a place of infamy in the history books. Perhaps Ed should have recognized it as an omen.

Though Ed cherished a golden image of what constituted a soldier, someone apparently forgot to inform the men at Fort Grant. Except for a rare exception, the officers were fat, drunk, and concerned more with avoiding work than drilling their men. The form of labor they deemed appropriate for the enlisted men was building roads in the middle of nowhere. Moving huge boulders and digging ditches drained the men's strength as well as their morale.

Between bouts with dysentery and incompetent doctors, chasing after but never finding renegades and bandits like the Apache Kid and Black Jack, and cleaning out the stables, Ed's disenchantment grew. He despaired of ever achieving the kind of military glory he desired. To add insult to injury, during one of his stays in the fort hospital, one of the chronically drunken doctors diagnosed Ed as having a weak heart and recommended that he be discharged. When headquarters requested a second opinion, the junior doctor reached the same conclusion...an unsurprising result given that the doctor would be reluctant to contradict a superior officer. As bad as Fort Grant was, it could always be made even more despicable by a creative superior. Whether Ed really had a "weak heart" at that time is questionable.

In any event, since a diagnosis of heart disease made it extremely unlikely he would be able to obtain an officer's commission, Ed appealed to his father for assistance. Calling upon old friends, George Burroughs arranged for his young son's discharge from the Army in 1897.

With his quest for a military career crushed, Ed once more found himself adrift with no clear direction to follow. Calling upon the artistic bent he had evidenced at the Michigan Military Academy and during his lonely hours of sketching at Fort Grant, Ed briefly attempted to study art in Chicago. To his disappointment and his father's relief, he rapidly discovered that becoming a professional artist required more than a facility at drawing horses. The long hours of study and practice looming ahead dissuaded Ed from what his father viewed as a disreputable career.

A Cowboy in Idaho

Once again seeking escape in physical action, Ed moved out West to help his brothers Harry and George, Jr., on their cattle ranch in Idaho. Though not contributing a great deal to his older siblings' ranching operation, Ed did continue to display his remarkable affinity for horses and for encountering unusual characters. Through kindness and determination, he managed to tame and ride horses all the other cowhands regarded as man-killers. Through innocence and luck, he survived encounters with hired gunmen and characters well-deserving of the label "loco."

While enjoying the demanding yet invigorating outdoor life far from traditional civilization, Ed caught wind of the war brewing between the United States and Spain. With the sinking of the Main in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, in 1898, the Spanish-American War swung into high gear. Breathing fire into the smoldering embers of his martial dreams, Ed quickly contacted Teddy Roosevelt and sought to obtain a commission with the eventually-to-be-president's Rough Riders. Once again, however, he was to be disappointed. Teddy had more than a sufficient number of volunteers and could not afford to bring down someone from such a great distance as the wilds of Nineteenth-century Idaho.

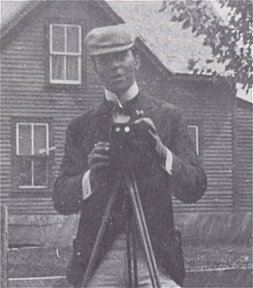

1898 photo of Ed

with camera and tripod in Pocatello

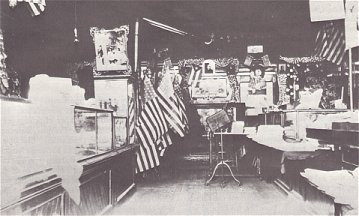

Interior of Ed's Pocatello

stationery and photography storePerhaps recognizing that his kid brother lacked a certain something as a rancher, Ed's brother Harry helped set him up for business in a stationery store in Pocatello, Idaho. A forerunner of today's drugstores, "Burroughs'" offered newspapers, books, magazines, and cigars to the residents of Pocatello. In addition, Ed employed a woman who developed and printed Kodak pictures sent in by mail from customers around the country.

His initial creative efforts at marketing notwithstanding, Ed rapidly tired of the monotony and routine. After selling back the store to the previous owner, Ed again went to work for his brothers. The ranching life proved no more congenial than before. In 1899, Ed made the move back to Chicago and took a job in his father's storage battery factory.

For awhile, Ed stuck to the grinding task of learning George Burroughs's business from the ground up. The new century did see one positive change in his fortunes. After ten years of constant rejections of his proposals, Emma Hulbert agreed to marry Ed. After the wedding in 1900, Ed received a raise in wages from fifteen to twenty dollars per week. Combined with numerous meals consumed at the home of his in-laws, Ed and his new bride had a bright start to their lives together.

For three years Ed managed to contain his wanderlust. The promise of gold in the rivers of Idaho, however, proved too much for his resolve. Rejecting a steady income and relative security, Ed packed up his wife and dog and returned to Idaho to help his brothers operate a gold dredge. Unfortunately, Ed found long walks with his wife in the woods more congenial than putting in his fair share of manual labor on the dredge.

After a heated discussion with his brother, George, over the issue of what constituted appropriate behavior, Ed decided to join his brother, Harry, who had moved to Parma, Idaho, in order to work the rivers of nearby Oregon. In the course of this journey, Ed made an ill-fated attempt at gambling. With no money but still with a wife and a dog, Ed contacted Harry for funds to complete the trip.

Though he managed to stay with the business this time until it failed in 1904, Ed still retained hopes of landing a better career in art. He even managed to complete two or three correspondence courses before he faced the stark fact of unemployment.

With help yet again from Harry, Ed became a railroad policeman for the Oregon Railroad Company at one of their branches in Salt Lake City, Utah. In keeping with past endeavors, Ed's imagination outpaced the reality of his position. Dreams of quickly working his way up the company ladder to possession of his own luxury rail car soon shattered on the rock of too many drunks to arrest and too little money to spend. To conserve what few funds he possessed, Ed half-soled his own shoes. To preserve the dignity of his wife, he did the laundry and helped out with the household chores.

Railroad Policeman

Before a year was up, Chicago and home began to regain their appeal for the not-so-newly-wed couple. Auctioning off the furniture and "junk" they had dragged with them throughout their journeys in the West, Ed and Emma returned to Chicago in style. The euphoria proved to be short-lived.

With work tough to come by in the big city, Ed took employment as a timekeeper at a construction site, sold light bulbs, candy, and books of lectures door-to-door. With a little luck, he latched onto a job as an "expert accountant." Though he knew nothing about accounting, Ed's employer knew even less. As Ed wrote later, "what are commonly known as the breaks, good or bad, have fully as much to do with one's success or failure as ability." Given the tremendous amount of effort he later exhibited in his writing career, Ed was perhaps overstating the case. Yet he did recognize that often it is the unexpected and our ability to recognize and capitalize on those "breaks" which lead us out of failure and on to success.

Unfortunately, throughout much of his early life, Ed heard opportunity knocking many times but displayed an uncanny knack for opening the wrong doors.

The only people who never fail are those who never try.

~ Ilka Chase.Seeking greener fields, Ed left accounting by his own decision. After flirting with a military career again by chasing after a commission in the Chinese army, he accepted a position in 1907 with a company in the mail-order business: Sears-Roebuck. Before long, he worked his way up to manager of the correspondence department. With ingenuity and attention to detail, he streamlined the operations of the department and succeeded in increasing productivity with fewer employees. His efforts even brought him to the attention of Julius Rosenwald, the head of Sears-Roebuck. At long last, Ed had apparently found his niche: a responsible and well-paying position with a major American company.

With this newly-won security, Ed and Emma decided to have a child. Their daughter, Joan, transformed the couple into a family in 1908. Then, in a move which shocked friends, relatives, and in-laws, Ed took an action that most people would label irresponsible, reckless, and downright stupid. Having finally achieved a good job with excellent chances for advancement, at the age of 32 Ed quit Sears-Roebuck and went into business for himself with a partner.

Within a year, Ed found himself pounding the pavements again. To increase his burden and, perhaps, his sense of guilt, his son, Hulbert, added a hungry mouth to the family in 1909.

Alcola

With no success, Ed sought a job on his own. In a recurring role as guardian angel, his brother Harry rescued him from disaster and got him a job with Physician's Co-Operative Association placing ads in pulp fiction magazines for a "cure" for alcoholism. Unfortunately for Ed, the FDA decided that the cure was worse than the disease and banned the sale of "Alcola."

Taking another crack at being an entrepreneur, Ed developed courses in salesmanship which he and a partner sold to other would-be salesmen. While Ed wrote the courses designed to teach students how to sell aluminum pots and pans, more often than not, the students simply quit in the middle of the course or failed to send in the money for the pots they did manage to sale. During this rocky period, Sears-Roebuck contacted Ed about taking another position with the company. Facing incredulous relatives who must by then have been convinced that Ed was destined to be a failure, Ed declined the offer. While as a world famous writer he could later say that "occasionally it is better to do the wrong thing than the right," with a wife and two children to support in 1909, Ed doubtlessly entertained silent thoughts that perhaps his elders might be correct about him and his apparent foolishness.

When at last his business did collapse, Ed found himself staring at far too familiar a situation: no job, no money, and relatives growing more and more exasperated with his seemingly incredible behavior. Ed was soon reduced to pawning his wife's jewelry and his watch to buy food for his brood. He had reached the depths and he did not find them to his liking.

"I loathed poverty and I would have liked to put my hands on the party who said that poverty is an honorable estate. It is an indication of inefficiency and nothing more. There is nothing honorable or fine about it." Whether poverty does result from "inefficiency and nothing more" may be debatable, but there is no debate that Ed was well-acquainted with its face...and its motivating power.

A man can fail many times, but he isn't a failure until he gives up.

~ Anonymous.Convinced that success meant success in business, Ed hired agents and attempted to make a go of selling pencil sharpeners. Limping

along with this scheme, he eventually found himself with more time on his hands than sales and about ready to give up.It was 1911. Ed was 35 years old, approaching middle-age and with a wife and two small children to support. For a man of his age, common wisdom dictated that he be settled into a financially comfortable position somewhere for the security of his dependents. Even if he was miserable performing some job, his peers and elders might have argued that he had no business jeopardizing the welfare of his family. To be a good father and husband, he should have suffered in silence and done what society expected of him: simply provide the necessities of life for those who could not and abandon his childish hopes for the future.

At this juncture of one more failed business venture, Ed was almost ready to concede that he was, indeed, a failure, that all of his struggles added up to nothing. In the midst of combating poverty and suffering, he had to wage a more elusive battle with his feelings of hopelessness, frustration, and regret. Yet Ed had always chosen the path less traveled. He had never given up his search for an occupation that was both personally meaningful and financially rewarding. His failure-hardened will to succeed refused to let him rest with less. It was simply not in his nature to brood over failure. For Ed, the proper course to follow was to take positive action to deal with the failure at hand and to move on, even if the destination loomed hazily, at best.

Despite a lifetime of thwarted dreams, Ed remained unafraid to take risks, to avoid the safe, secure route and to seek, instead, for uncharted lands. Highly imaginative and energetic, he could never remain satisfied for long with a mundane job. Refusing to yield to discouragement, he preferred to try to solve problems -- even if he failed in the attempt -- than passively to accept conditions which others might judge to be inevitable. If he had done as so many of us might have and listened to the admonishments of family and society and those inner demons and fears of his, Ed might have taken the position at Sears and never written a word of fiction.

Fortunately for the millions who have read his stories over the past eighty years, he did not.

In desperation, Ed began work on his first novel at the age of 35. With typical self-confidence, he decided he could produce stories at least as entertaining as those he had read at his newsstand in Pocatello, Idaho, and in the pulps where he had placed ads for Alcola.

Knowing little or nothing about professional writing or the publishing game, Ed wrote and then submitted half of a novel to Thomas Metcalf, editor at All-Story Magazine. "I was writing because I had a wife and two babies," he later wrote, and not from any particular artistic urgings or love for writing...a perhaps disingenuous statement given the drawings and tales he had concocted for his family and friends over the years. In any event, recognizing a good yarn, Metcalf purchased Ed's story for $400.00 and published it in 1912 as "Under the Moons of Mars" (The Princess of Mars in book form).

At age 36, Ed Burroughs had become a published author...but under the pseudonym, Norman Bean. (He had written the tale as "Normal Bean" [common head]. Perhaps he feared to have one more failure linked with his name or perhaps he yet believed he would ultimately succeed in business and thought it might hurt him to be associated with such wild stuff.)

In the midst of Ed's first literary adventure, his brother Coleman secured a job for him with the Champlin-Yardley Co., a maker of scratch pads. Like most of his encounters with the business world, Ed soon had to leave; his brother's business simply could not support two families.

On a suggestion from Metcalf, Ed wrote a second novel, The Outlaw of Torn, an historical tale set in the time of knights and damsels. Ed was stung and shaken when Metcalf rejected the piece. Other rejections followed. Still needing a regular income, Ed took a job in 1912 as a department manager for a business magazine put out by the System Company. The position satisfied him no more than had any of the other myriad jobs he had endured over the prior decade and a half.

Despite the rejections for The Outlaw of Torn, Ed decided to give writing another try. Scribbling on the backs of old letterheads on weekends and holidays, he spun out a most unusual tale about an infant adopted by a tribe of great apes in Africa and raised to adulthood. The result was Tarzan of the Apes, a novel for which Metcalf paid the fledgling author all of $700.00. In quick succession, Ed wrote The Gods of Mars and The Return of Tarzan. The latter was rejected by All-Story. Ironically, its acceptance by New Story magazine, a rival publication, opened Ed's eyes to new marketing possibilities. Another milestone in his life was the birth of his last child, John Coleman, in 1913.

With his new-found success, Ed quit System and moved his family to California. While Harry advised him to be cautious and remain at work, Ed itched to explore this new universe of writing and publications. It was a universe he eventually conquered as few have before or since.

Given Tarzan's worldwide fame and integral place in our culture (his name can be found in any reputable dictionary), it may seem odd to modern readers to realize that half a dozen publishers rejected book publication of Tarzan of the Apes. Even its eventual publisher, A.C. McClurg, printed it only after first rejecting it...and then only after its serialization in a number of newspapers -- and Ed's persistence lobbying -- proved the popularity of the inimitable Apeman.

Over the past eighty years, the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs have appeared in magazines, books, motion pictures, radio, and comic strips. ERB became the first author to incorporate himself and even founded his own publishing company to print his novels. Tens of millions of copies of his nearly seventy books have appeared in dozens of languages...even in Braille.

Yet throughout the nearly four decades in which he wrote, ERB continued to struggle against rejections of his works, fought against those who attempted to cheat him, and maintained his love of the military man. (During World War II, Ed did finally manage to reenter the periphery of combat as a war correspondent in the Pacific theater.) Whatever his setbacks, however, Ed Burroughs never abandoned his ideals, his visions for himself and his future. His determination to succeed outshone his problems and his recurring feelings of inadequacy and doubt.

He wrote, "I think there is a moral lesson in (my life's) story. It might even be a paradox: we win when we are defeated." Edgar Rice Burroughs was defeated many times, yet he was never a loser.

Like any inventor, entrepreneur, explorer, or innovator, ERB followed his own star. Some people today may read his biography and think him an undesirable role model given the risky actions he took. Yet such people would likely conclude the same about any individual who bucked the mainstream and struck out on his own path. They forget that only those willing to take risks, willing to ignore criticism and doubts (their own as well as others!), only those with the will to experiment with something new and unproven give us the progress the rest of society takes for granted.

The Necessity of Failure

Our ancestors would have understood what motivated Ed in his quest for success and how he was able to face repeated defeat and failure. It was our forebears who left the comfort and safety of the eastern seaboard and headed out into the wilderness on what must have seemed to many of their fellows to be irresponsible, foolhardy undertakings: how dare they expose their families to such unpredictability and danger!

But those who founded and expanded our nation knew that the potential rewards were worth the risks and hardships they endured. They had the political freedom to smile at their detractors, at those fearful of venturing out into the unknown, and to act according to their own decisions. Those pioneers knew the benefits would be their own if they succeeded...and the punishment theirs, as well, if they guessed incorrectly.

What our ancestors would not have understood is the notion that the proper function of government is not to protect our rights but to protect us from failure. They would have shaken their heads incredulously at the ideas which so many of their descendants take as givens-not-to-be-questioned: that citizens in this country need a government-supplied "safety net"; that some businesses are "too big to fail"; that social assistance to unsuccessful citizens should be accomplished by coerced, involuntary "charity"; that governments should license a growing number of professions in order to "protect" the clients of those professionals; that we should be "protected" from ourselves, that is, from our own choices and voluntary actions, by such agencies as the FDA, FCC, EPA, and the thousands of laws they and others administer all the way from the local to the national level; or that the responsibility for our lives lies not in our own hands but in those of faceless politicians and bureaucrats who have never met nor known us and never will.

Today, educators seek tenure; businesses request tariffs, quotas, and cartels; scientists hope for never-ending government research grants; individuals demand that health care, social security, education, housing, food, and a thousand other things be provided them regardless of what they themselves have done or failed to do. All of them view risk and its attendant possibility of failure as something inherently bad which must be averted by any means and at any cost.

I Still Live

Ed Burroughs, however, possessed the kind of spirit which originally distinguished our nation from all others. Even now, examples of that spirit are as numerous as the people who struggle every day in the face of growing restrictions, regulations, and taxes for a better life for themselves and their families. We may hear only about the famous ones, but these men and women known only to their acquaintances share qualities all successful people exhibit. Their attitudes and actions are expressed in any number of folk sayings: necessity is the mother of invention; if you try often enough and long enough you're bound to succeed (the law of averages); we should learn from our mistakes; never say die. Pick your own. For the first of ERB's heroes, John Carter of Mars, it was, "I still live!": as long as he remained alive, he would continue to struggle to win no matter what the odds or how hopeless his situation seemed.

Edison and his associates tested 10,000 different materials before they discovered one suitable for the filament in electric light bulbs.

Col. Sanders tried hundreds of restaurants before he found one who'd try his chicken recipe.

Henry Ford went bankrupt twice before finally succeeding with the Model T.

Gregor Mendel only started breeding plants after failing to become a teacher.

Fred Smith founded Federal Express in 1971 but nearly went out of business before demonstrating to his customers the value of his service.

Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.

~ Thomas EdisonEntrepreneurs of all stripes learn what they need to know only after suffering through one or more failed businesses.

Actors, artists, and writers learn that their "instant successes" rarely come without years of toil and repeated rejections.

Scientists and researchers realize that only by being given the opportunity to fail will they ultimately succeed. On the frontiers of knowledge, there are no road signs. Finding the proper path requires pursuing innumerable blind alleys.

Freedom to succeed demands the freedom to fail. Only when we are required to face the consequences of our mistakes will we learn how to proceed and find the motivation to try. Only when we are required to accept responsibility for our own choices and actions will we gain self-confidence and self-esteem. Only when we realize that we can never guarantee success will we learn that we can guarantee failure. No "social safety net" will provide us with what we should discover on our own.

Such a safety net might have spared Ed Burroughs and his family some physical hardships, but it would also have kept him from exploring that dimly seen path which led to his eventual success. For Ed, poverty was a great motivator. It kept him trying new avenues until he found the one that best matched his talents. Despite his early lack of money, he ensured that his children had the necessities of life and grew up in a loving family. Rather than appealing to government for assistance, ERB looked where he should have for help: to his friends, his family, and, especially, himself.

Too many today would criticism Burroughs for the choices he made. They forget for themselves what they try to teach their children. To grow and mature, young people need to learn that mistakes entail consequences/costs/losses; that they need to learn from their mistakes how to proceed correctly; that they must then perform those actions which will lead to the fulfillment of their goals; and that such success will bring them the rewards/gains/profits which will help motivate them to reach for values in other areas of life and help them persevere in the face of obstacles and opposition. Our children need to "unlearn" helplessness.

We teach our children to "look before you leap," that is, to be proactive rather than merely reactive; to consider the pros and cons, costs and benefits, of a situation and, if possible, learn to avoid mistakes and sacrifices in the first place. We tell our children, however, that when they do fail (and they will; none of us is infallible or omniscient), they should accept the situation and move on. "Crying over spilled milk" only wastes energy and resources which could be devoted to solving the problem. Indulging in useless recriminations or blaming others for our failures accomplishes nothing.

We teach such things to our children. We should remember to apply them to our own lives, as well.

Forcing others to cushion our failures stifles innovation, learning, the acceptance of self-responsibility...and the development of self-confidence and self-pride. Edgar Rice Burroughs would have been the first to recognize the fact that no matter how well intentioned you are, sometimes the best thing you can do for someone is nothing.

N.B. The biographical information for this article comes from Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Man Who Created Tarzan, by Irwin Porges, Brigham Young University Press, Provo, Utah, 1975.

|

Russell Madden has sold both nonfiction and fiction and is an affiliate member of the Science Fiction Writers of America. He teaches writing at a community college in Iowa. He was twelve when he discovered ERB via The Land That Time Forgot in a bookmobile parked outside his school. For over four decades, he has remained a fan of a writer who had a profound influence on his life. |

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2010 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.