CHAPTER VIII - SLIPPING

THE SURLY BONDS OF EARTH

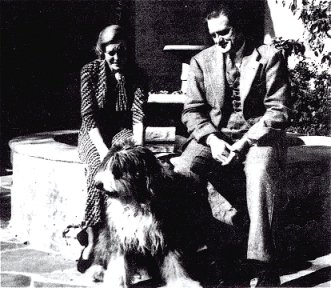

Joan ~ Tarzan, the Sheepdog ~ Jim

Photo by Hulbert Burroughs ~ January 1, 1935

The Burroughs family decided in the late 30s to buy an airplane from

Jim Granger who had a flying school at the old Santa Monica Airport. It

was a side-by-side, single-wing, open cockpit that was not speedy but very

stable and ideal for beginners. I had already started to obtain a private

pilot's license, and was thrilled that Mr. Burroughs became interested.

Both boys, Hulbert and Jack Burroughs, were also taking lessons. Even Mrs.

Burroughs had visions of taking it up.

Unfortunately,

Hulbert had a bad crash on a takeoff. He was not seriously injured, but

the event put a damper on the family's flight program. They soon gave it

all up and sold the aircraft.

Unfortunately,

Hulbert had a bad crash on a takeoff. He was not seriously injured, but

the event put a damper on the family's flight program. They soon gave it

all up and sold the aircraft.

I continued flying, and went from a private license to a commercial

ticket. The bug had bitten me good and I needed the extra money to supplement

the lack of income from acting. So I decided to change my hobby into a

business venture. I leased a large hangar at the Van Nuys airport in the

San Fernando Valley, and opened a flying school. Along with the school,

I provided hangar space for several owners of private planes as well as

maintaining a licensed repair station. I secured a dealership for the Interstate

aircraft which became quite popular, and sold several of them. I also bought

and sold used planes.

I had students galore and three full-time instructors teaching like

mad. In 1937, I originated the National Airmen's Reserve, a forerunner

of the Civil Air Patrol The plan was to provide aeronautical training for

civilian pilots, prepare them as a reserve force in case of war, and find

them paying jobs after they completed the course. As I said in a speech

at a service club at the time, "We are not in sympathy with war. We want

to prevent war by building a sufficient defense against it."

The idea was quickly endorsed by the North Hollywood and Van Nuys Chambers

of Commerce, the National Defense League, and publisher Bernard McFadden.

We established our national headquarters at the Adams Port in North Hollywood.

I served as national secretary, with the assistance of Charles McBrien,

head of the charter chapter. The first group of pilots was named the Ken

Maynard Escadrille in honor of the Western star who was as handy with a

plane as with a horse. Incidentally, Mr. Burroughs gave Ken permission

to name his horse Tarzan.

To promote the idea, we started a weekly program on local radio; originally

on KMPC, and later on KFAC. The show featured interviews with guests, like

Maynard and racing pilot, Marion McKeen, who taught me how to fly. American

Airlines stewardess, Wilma Cannon, "Queen of the Airlines," even christened

our first plane.

The show also featured a short aviation serial I wrote and directed,

in which passengers on the Silver Hawk sports monoplane took a goodwill

flight to South America and encountered many dangers. My frequent co-star,

Harold Goodwin, appeared regularly in future roles, along with Jack Leamley

and Joan Allan (Joan Pierce was her real name).

Speaking of Ken Maynard, I would like to mention here that Ken and Kermit

Maynard were as unlike as day and night in life styles and personalities.

Kermit was the quiet reserved type and very athletic. Ken was a rooten

tooten high roller. Every night was SAturday night and his night to howl.

Ken was two or three years older than Kermit and was a top HOllywood

western star when Kermit came to Hollywood. Kermit had to take any kind

of acting job he could find as a stunt man or extra. He bought a horse

and in his spare time taught himself to ride and rope and soon became a

Rodeo attraction as a trick rider and roper.

Although the two brothers were never very close, Ken saw an opportunity

to use Kermit as his double and stunt man. It was not too long before the

western producers saw Kermit as a potential star in his own right. Kermit

had in the meantime won many Rodeo championships in trick riding and roping

including the famous Calgary Stampede in Canada. The result of which put

him in the world championship class.

He was soon signed to a contract to star in his own series of Westerns

and North West Mounted stories. These were successful and being prudent,

he saved his money and prepared for the future. I worked in many of his

pictures and we were fast friends all our Hollywood days. We went all the

way back to our football playing college days. Kermit passed away a few

years ago very suddenly from a heart attack.

Ken died a little later practically penniless, in the motion picture

home, he lived up all his fortune having lost most of it in a Circus

he put together that was a miserable failure. He took it on the road for

a season or two and in spite of pouring a fortune into trying to make a

go of it, it folded. At one time he was one of the richest stars in the

movie business.

Kermit on the other hand left a nice comfortable future for Edith and

his son bill. He had made some sound investments in real estate that left

his wife and son financially secure. His son is now one of the best office

and store interior designers in the area.

In 1941 Joan and I were so sure of financial security that we designed

and engaged a contractor to build us a new home in what is now Sherman

Oaks. It was called Van Nuys in those days. It was about six miles from

Hollywood in the San Fernando Valley.

Spanish design and featured a lot of original ideas. It had the first

knotty pine paneled kitchen in the area. We also had the first used-brick

fireplace and mantle that anybody had seen in that part of the country..

Later on, they became quite popular and used-brick became very expensive.

I got mine just by going down to Los Angeles with a truck and some workmen,

and gathering it up for free from a building being torn down.

In June 1941, we moved into this new house. Business was great and the

change from acting wasn't regretted. Then came December 7, 1941, a day

of infamy in a literal way for me. The government red-flagged every airport

in t eh country and we were closed down. The planes were grounded and the

air reserve project was blown sky-high.

Next day, a federal inspector said I would have to dismantle all the

aircraft, close my business, and store the airplanes (engines in one place,

fuselages in another). We had one other choice, however. We could fly them

out of the prohibited zone of 150 miles from the coast -- within one week.

Luckily, I knew a little strip I had landed on a few times, just east

of Blyth across the Colorado River at Quartzsite. There was one store and

a filling station there, owned by Buck O'Connor. He was a typical "desert

rat," but interested in flying and ran a little ranch in Quartzsite. He

wanted to assist in the war effort, and said I could use his field for

nothing.

I told him I would be over with all the equipment, but there was one

problem. There wasn't any hangar and the planes would deteriorate in

the heat because they were made mostly of fabric.

Fortunately, a fellow named Krafft, who owned a traveling circus was

storing his Beechcraft with me. He was an excellent pilot. He didn't want

to store his airplane and dismantle it, so he offered to send the crew

and one of his tents to Quartzsite to get our planes under cover. Before

the week was out, we had a flying circus of twenty-five airplanes under

the big top. We knew we couldn't stay there long because there was no profit

in desert plane storage.

I knew about an

abandoned hangar about four miles out of Nogales, Arizona, which is a gateway

to Mexico. A rich fellow owned a ranch, including this hangar and landing

strip. He had taken up flying as a hobby and intended to run a dude ranch

for flyers. He soon soured on the idea, sold his ranch, and donated this

land and the hangar to Santa Cruz County for an airport. Nothing happened

since Nogales was a small town and there was no interest in flying.

I knew about an

abandoned hangar about four miles out of Nogales, Arizona, which is a gateway

to Mexico. A rich fellow owned a ranch, including this hangar and landing

strip. He had taken up flying as a hobby and intended to run a dude ranch

for flyers. He soon soured on the idea, sold his ranch, and donated this

land and the hangar to Santa Cruz County for an airport. Nothing happened

since Nogales was a small town and there was no interest in flying.

The chairman of the county board of supervisors was Louis Escalada,

a student I knew at Arizona University when I was a coach. He arranged

permission from the supervisors for a lease on the field and the hangar.

We moved quickly from Quartzsite.

A crash program was under way to train badly needed pilots for the war

as fast as possible. I was known in aviation circles, so I as asked to

run a civilian pilot training (CPT) program. I also had an offer to go

into the transport service, flying big cargo planes all over the world.

But that would have meant leaving my family behind which I did not want

to do.

The field was all fixed up with county equipment and workers, who also

cleaned up the hangar. We had our own electric generator to run all of

our tools and equipment. The only use the hangar had seen for several years

was as a hangout for a state hunter. He had a bunch of dogs to hunt the

wolves and coyotes that invaded the ranches.

After the field was fixed up, we got the contract. We had to give these

students thirty-five hours of flying and ground school training, enough

to qualify them for the equivalent of a private pilot's license. We got

permission to use Nogales high school for the ground school. I scrambled

for all the airplanes I could buy or rent, and rounded up twenty-five light

planes. They were the trainer type: Cubs, Tailorcraft, and all kinds of

little "kites" as we called them. They were sufficient for beginning pilot

training.

November 1941 ~ Jim with Travelair with "Comet Engine"

Instructors

weren't hard to find because CPT jobs exempted them from military duty,

and a lot of them didn't want to go to war. For instance, one Jewish fellow

I had known in Van Nuys at my pilot training school said, "I changed my

name because I thought I'd have to go into the regular army as a pilot

and I didn't want to be forced down in Germany with a Jewish name." After

he got the job, he reverted to his original name.

Instructors

weren't hard to find because CPT jobs exempted them from military duty,

and a lot of them didn't want to go to war. For instance, one Jewish fellow

I had known in Van Nuys at my pilot training school said, "I changed my

name because I thought I'd have to go into the regular army as a pilot

and I didn't want to be forced down in Germany with a Jewish name." After

he got the job, he reverted to his original name.

I even had a couple of women instructors, one by the name of Marguerite

Gambo, who brought in ten airplanes from Honolulu. When Pearl Harbor hit,

she was running a successful operation at Hickam Field. She was the daughter

of one of the Dole pineapple people an d used her influence to get permission

to ship her planes to the mainland.

They were dismantled and stored at the Glendale airport with Charley

Babb, a plane broker. He knew I had been looking for planes, so he got

us together and I made a deal to buy them. We sent pilots over to Glendale

and ferried them back to Nogales as fast as we could. At the same time,

I gave her a job as an instructor, and she proved excellent. She had a

four-place Fairchild that we used for profitable charter work out of Nogales.

Nearby, Fort Huachuca had a lot of officers and government men who wanted

to get out occasionally to visit Tucson, Phoenix, or El Paso. I was the

only private operator permitted to fly into this government base.

My credit was good and a banker in Tucson backed the project with all

the money I needed. A senator that my dad and I knew from Indiana, Frederick

Van Nuys, was on the CPT Committee, and got Nogales designated a Class

A International Airport. This gave us room for more students, and planes

from Mexico could land while American planes were cleared for going into

Mexico.

The Pierce Flying

Service was gaining altitude fast, but it almost ended in a tailspin near

Prescott, Arizona in 1943. I was taking delivery of an old Travelair with

a Jacobs engine that was to be sold into Mexico. It had been overhauled

and inspected, and certainly seemed airworthy when I checked it out. During

the night, a cold front brought freezing temperatures and snow to Prescott,

which called itself the mile-high city.

The Pierce Flying

Service was gaining altitude fast, but it almost ended in a tailspin near

Prescott, Arizona in 1943. I was taking delivery of an old Travelair with

a Jacobs engine that was to be sold into Mexico. It had been overhauled

and inspected, and certainly seemed airworthy when I checked it out. During

the night, a cold front brought freezing temperatures and snow to Prescott,

which called itself the mile-high city.

Despite the weather, I took off the next morning with a female pilot

who was to drop me off in Nogales on her way into Mexico to deliver the

plane. After five minutes in the air, the engine began to cough and sputter.

We thought the carburetor heater was engaged, but it had disconnected when

we pulled on the control to activate it. The carburetor was quickly iced

up and the motor conked out.

We climbed only about 1,500 feet and there was total silence, the greatest

and most frightening silence one could ever experience. We were too low

to turn back as all pilots will understand -- turning back toward the field

on a dead engine at this altitude is fatal.

Straight ahead was a lake, called the Dells, filled with jagged rocks

and spires. The only thing to do was glide toward the lake and hope to

land safely in it or along its narrow twenty-five foot shoreline. Unfortunately,

the air was thin at such high altitudes, reducing glide distance. The plane

began to settle fast and we had to fight a stall that would send us into

a fatal tailspin.

Though the pilot had logged lots of air time, she froze in panic. When

she wouldn't release the controls, I socked on the chin and got back on

the glide path. In a few seconds, she came to and began screaming, "We're

going to die, we're going to die!" My assurances that we would make it,

along with the realization that she wasn't flying the plane anymore, calmed

her.

It appeared we were going to reach the lake or the shore. I had already

cut the ignition switch because the tanks were filled with high octane

fuel that could be set off by a spark. No sooner had I sighed with relief

than a huge ditch loomed up. The water flowing into the lake from the surrounding

rocks and mountain had cut a deep gash that looked like the Grand Canyon.

It was too late to change course, I prayed that I could stretch the

glide to pass over the ditch, but the plane would respond no longer. It

stalled out five or six feet short of the ditch. In one bounce, the entire

landing gear and wheels hit the ditch and sheared off. We shot forward

on the plane's belly, to the accompaniment of sparks, smoke, and the most

unearthly noise I ever heard. The woman fainted before we finally slid

to a stop.

I jumped out of the plane, ran around to the left side, even faster

than a golden lion, and dragged her out. I had taken only a couple of steps

back to retrieve the luggage when the plane exploded. The blast knocked

me down, but I managed to scramble for safety and pull the pilot, who was

now awake and screaming again, away from t eh flames and intense heat.

After I calmed her down (without any sock on the chin this time), we watched

the plane burn until only the fuselage frame remained. It resembled the

bones of a huge condor.

Dazed and bewildered, we climbed out of the Dells and trudged through

the snow until we came to a road. Eventually, we were able to hitch a ride

into Prescott. I knew some people there, as I did in almost every town

in Arizona, and they took us in. After a couple of days of filing reports

with the Civil Aeronautics Board and the insurance company while their

representatives examined the wreck, we were flown to Nogales by the operator

of the Prescott airport.

I felt little reaction to the ordeal until a delayed reaction jolted

me a few days later. Then I thanked the Great Pilot in the heavens profusely,

and with good reason. Everyone agreed that the ditch was our salvation.

The terrain along the shore was so rough that it probably would have caused

a fatal cartwheel. The belly landing saved us.

Another experience I will long remember was on a charter flight. I had

an arrangement with the hotels and dud ranches in the area, which were

numerous, to provide charter flights for their patrons whenever needed.

I mad many trips to almost all cities in the south western area. Denver,

El Paso, Alberqueque, Grand Canyon, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Tucson and

many others too numerous to mention. They ere all routine and profitable.

Nothing exciting ever happened.

However, on one particular day it turned out not to be so routine. The

Casa Grande Hotel in Nogales phoned me for a flight to Phoenix for two

of their guests. The time was set and the hotel limousine arrived at the

field with the two people for the trip. A man and a woman.

As they got out of the car I noticed the man was "bombed" out of his

skull -- drunk as a skunk. He was rubber legged and had to be steadied

by the chauffeur and the woman in order to walk. "Just a minute," I called

out from the door of the office. "Sorry, but the flight is off. I can't

fly an intoxicated passenger -- it's C.A.A. regulations (Civil Aeronautic

Administration) and also against my policy."

The chauffeur sidled up to me and in a sotto voice said, "Do you

know who these people are? It's Mr. and Mrs.. William Freeman of Honolulu.

They own the largest pineapple ranch and packing house in the world."

Mrs. Freeman called out, "Mr. Pierce, I can handle the situation. Trust

me. We have to get to Phoenix as soon as possible."

She was a breath taking beautiful blond and her charm and earnest plea

almost bowled me over.

"Oh please, please," she continued, "I promise there will be no problem."

"Whash a matter - whash a matter, " spoke up Mr. Freeman. "Let's get

out of this one horse town. I wanna drink -- I wanna drink." With that

he pulled a flask out of his pocket and started to open it. Mrs. Freeman

grabbed it out of his hand and gave it to the chauffeur.

With her looks and charm, I figured she really could handle just about

any situation, so I gave in and said, "O.K. We'll give it a go."

We poured him into the plane and off we roared toward Phoenix in a Waco

QDC, 4-place plane with a 350 horse power Jacobs engine.

In about fifteen minutes we had more or less settled down. Mr. and Mrs.

Freeman were in the back seat. I was hoping he would pass out, but no such

luck. He kept yakking for a drink. "There isn't any. You will have to wait

till we get to Phoenix."

"Well, I'll have a cigarette then and no one is going to stop me," he

yelled.

He reached in his pocket for the pack and Mrs. Freeman grabbed his arm.

All Hell broke loose. He started mauling her around and calling us all

kinds of vile names. He made a pass or two at me that I managed to duck.

"Could I light a cigarette and hold it for him?" she asked in a pleading

voice. "I will hold it and he can have a few puffs.

By now he was really violent.

"O.K. - O.K.," I yelled. "Let him smoke but be careful. This plane is

covered with inflammable fabric and a spark could blow us to kingdom come."

Very carefully, Mrs. Freeman lighted a cigarette and held it to his

mouth while he took several puffs. Suddenly he decided he did not like

this spoon fed smoke and grabbed for the cigarette. In the scuffle the

cigarette flew out of her hand as she screamed, "Oh my God, it's behind

the seat," she cried out.

"Unbuckle your seat belt and turn around and see if you can find it

and hurry," I said.

After a few seconds she called out, "I can't see it -- I can't find

it." She was now almost hysterical.

"Fasten your belt. We are going down for a landing and fast," I yelled.

Craning my neck in all directions I suddenly spotted the Air Force Base

at Chandler. Dead ahead about five miles away.

"Here we go," I yelled and like a dive bomber I headed for the field.

I had no radio for permission to land and had to take the chance on

being arrested for landing on an Armed Base in wartime without a permit.

Military planes were ducking and dodging me on all sides. I picked the

runway closest to me and plopped won, down wind yet. Slammed on the brakes,

jumped out and pulled the passengers as though they were two sacks of wheat.

By now Military Police jeeps and fire engines were coming at us with

sirens blasting. When they arrived, I explained our predicament and received

kindly treatment immediately. We observed the plane from a distance for

a few minutes and nothing seemed to be happening. No smoke or anything

unusual.

I told them that I would like to go aboard the plane and find the cigarette

if possible. They assured me they would keep the chemical hoses trained

on the plane as I climbed aboard. I scrounged around behind the seat and

found the half-smoked cigarette. Evidently the hassle of trying to get

the cigarette away from Mrs. Freeman had knocked the burning ashes off

the cigarette and there was nothing left to smoulder. I showed the stub

to the fireman and the MPs to assure them that it was indeed an emergency.

The excitement more or less sobered up Mr. Freeman. The MPs took my

passengers to their office to make out a report. I taxied the plane to

a parking area. After some time of questions and answers for the report

we were released and given a clearance to take off for Phoenix which was

just a few minutes away.

Landing safely in Phoenix did not end my problem with the passengers.

When I read my flight time meter (stool pigeon) and told them the amount

they owed me, Mr. Freeman said he did not have any money on him. Mrs. Freeman

only had a few dollars, not nearly enough to pay the bill. Freeman said

he would send me a check.

"No dice," I said and turned the meter back on. "I'll just wait till

you come up with cash and you figure out how you are going to do it."

I had their luggage locked up in the baggage compartment.

"When I get the cash, you may have your luggage." As the Chinese laundry

man would have said, "No tickee - No washee."'

They called a cab and said they would go to their hotel, get the money,

and come back.

IN about an hour an assistant manager from the hotel returned with the

cash to pay off. I gave him their bags and he went on his merry way.

I immediately slipped the surly bonds of earth and headed for Nogales.

A feeling of peace swept over me as the flickering lights of Phoenix and

the silhouette of the beautiful Camel Back mountain faded into the darkness

behind me.

Raising my head I peered into the untrespassed sanctity of the Heavens

and said, "Thank you Lord."

Foot note: Years later, this most beautiful and charming lady divorced

Mr. Freeman, which is an anonymous name, and married one of Hollywood's

most famous actors.

Early in my Nogales venture, Joan rented our new home in Sherman Oaks

and she and the children came to Nogales for the duration. I rented the

best furnished house I could find, but it was a dump compared to what they

had just left. Nogales was an architectural hodgepodge, built on hillsides,

but a well-run town, made up of about half Mexicans and half Americans.

After a hard trip,

Joan, Mike, and Joanne arrived on the train they called the "Burro." It

took about two hours to get from Tucson, but something had happened to

make them two hours late. I could see by their reactions that they thought

they had arrived in the middle of nowhere. This railroad, which ran deep

into the interior of Mexico, was the type Pancho Villa might ahve hauled

his troops on during the Mexican Revolution. I remember that someone once

remarked as the "Burro" was coming out of Mexico, "Holy smoke! What happened

to Burro? It's on time today." It turned out exactly a day late.

After a hard trip,

Joan, Mike, and Joanne arrived on the train they called the "Burro." It

took about two hours to get from Tucson, but something had happened to

make them two hours late. I could see by their reactions that they thought

they had arrived in the middle of nowhere. This railroad, which ran deep

into the interior of Mexico, was the type Pancho Villa might ahve hauled

his troops on during the Mexican Revolution. I remember that someone once

remarked as the "Burro" was coming out of Mexico, "Holy smoke! What happened

to Burro? It's on time today." It turned out exactly a day late.

Even though we were together as a family, it did not work out. Even

the school frightened the children because most of the pupils were bilingual

and they weren't used to hearing Spanish. After two or three months, they

asked to go back to California. Mrs. Burroughs had a big home in Bel Air,

so they went to live with her. Any arrangement was better than having them

miserable.

Soon after their move to Bel Air, Mrs. Burroughs had a serious accident.

A bad fall resulted in a skull injury and a brain hemorrhage. Everything

was done to save her but she lived only a short time afterward. Joan was

with her at the time and it took a long while for her to recover from the

experience as Mrs. Burroughs was always a stabilizing influence. On birthdays,

Christmas, Thanksgiving, and other family get-togethers, she went all out

with wonderful presents and great meals. We all adored her because she

tried to help and council.

We couldn't get our house back because the Office of Price Administration

clamped a lid on everything. The tenants had a right to stay until the

war was over. I checked into a hotel in Nogales for the duration. I was

so busy that it didn't matter much where I lived except that I missed the

ones I loved.

I was the first on the field in the morning and the last to leave at

night, except for the security guard appointed by the FBI. He was also

a deputy sheriff, and I as appointed deputy, too.

The program ran smoothly without accidents or fatalities, and we ground

out pilots until 1945. Cadets who failed as pilots went on went on to become

navigators and aerial gunners.

When the war ended, I didn't try to make it in the private flying business

there because Nogales was such a small town. I sold all the surplus planes

to private operators in Arizona, California, or Mexico. I could have gotten

out of the lease, which stipulated it was for the duration of the war,

but I wanted to help the county get a new tenant and use this fine field

in peacetime.

Luckily, a fellow from New York bought a large abandoned hotel building

two miles from our field. It was spacious, and needed only some renovation.

The original organization went bankrupt, and the idea of a huge resort

and vacation spot, called "Rancho Grande," had flopped. This chap was a

wealthy businessman who owned a chain of dress shop franchises in key cities.

He was also a pilot, though not a good one, and owned his own four-place

Waco.

Like the fellow before him, he had visions of a fly-in dude ranch. We

negotiated successfully with a condition that I stay on to manage the airport

and live in his hotel for six months. He was a hard man to work for. The

business at the hotel was not what he expected, and the airport wasn't

doing much either, so he was full of sour grapes about the whole project.

He wanted to fly a lot and took me with him all over the country, along

with his very young wife and a large boxer dog that was nervous and ran

all over the plane. His plane had a "throw over" wheel which could be passed

from the left to right side of the cockpit. It was not exactly a dual control,

but more like a control and a half. I had only rudders and instruments

on my side. This didn't make me feel very comfortable, though occasionally

he would pass the wheel to me. He insisted on doing all the takeoffs and

landings, and staggered around on both. My eyes were popping out and my

hair standing on end most of these occasions. He yelled at me as though

I were his slave. I had hoped he would fire me, but I was stuck for six

months. I really rejoiced when I could finally return to California.

Meanwhile, my family had returned to our house, but not as soon as they

had wanted. The mother of the tenant had a terminal disease, and she pleaded

hardship to the court when we served the eviction notice. The lease had

run out but the court held in their favor, so we could not get back into

it until she finally passed on.

I was well-heeled, financially, but on the horns of a new dilemma. I

was supposed to get my old lease back on the Van Nuys Airport after the

war, but Lockheed had taken over the field under government supervision

to convert a flock of Army and Navy cargo planes to commercial use. I couldn't

tackle Lockheed, and there were no other desirable places in the area to

open up a flying service.

Hollywood was my first thought. I still had my Guild cards, both my

Class A actor card, and the miserable extra card. After a few weeks, I

managed to scramble up a few jobs from old friends, some speaking parts,

and one or two screen credit roles on Poverty Row. But it was soon evident

that tI was drifting back into the old heartbreak pattern.

Real estate was booming and I knew a few people in the business that

were making it big -- some of them former actors. After a night course

at North Hollywood High school, I took the state board examination and

passed. I was now a licensed real estate broker.

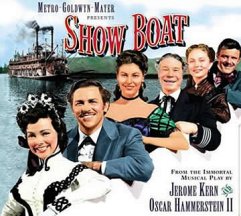

First I took one

more acting job, a part in Showboat

with Howard Keel, Ava Gardner, and Kathrine Grayson. I had a good bit in

it as a doorman. Most of it was cut in final editing, but some of the dialogue

remained. Hollywood might keep rolling along, just like the film's "Old

Man River," but I was now content to stay on the shore -- and sell it.

First I took one

more acting job, a part in Showboat

with Howard Keel, Ava Gardner, and Kathrine Grayson. I had a good bit in

it as a doorman. Most of it was cut in final editing, but some of the dialogue

remained. Hollywood might keep rolling along, just like the film's "Old

Man River," but I was now content to stay on the shore -- and sell it.

I immediately went to work for David Franzen, an acquaintance who was

happy to help me get some practical experience. His office was just two

blocks from our home. I bought a nice new Buick sedan to show prospects

around. I seemed to have a feel for the business and started out making

good sales.

Within six months, I decided to hack it alone, and rented an office

on Riverside Drive in Sherman Oaks. Soon I outgrew this cubbyhole, moved

to larger quarters in Northridge, where things were also booming, and took

on two salesmen.

Next, I was offered the sales agency of a huge tract being built in

Sacramento by Paul Trousdale, who became one of the largest developers

in Southern California and Hawaii. I kept my San Fernando Valley office

going and went to "Sacto," as we called it, to take on this gargantuan

task of selling 1,500 homes as fast as they were built. We sold one hundred

homes a month on an average at eleven to fifteen thousand dollars each

-- many to GIs exercising their housing rights.

Joan would drive up to Sacramento to visit me since I could never get

home once the job started. We went full steam seven days a week, but it

was Fat City, financially. When it was wrapped up, there was no question

that I had found my real calling -- selling real estate.

I kept one airplane and used it extensively to take aerial pictures

of property and land that I had listed. Customers were thrilled to fly

over property they were interested in. I also knew a photographer who wanted

to get in to the aerial business. I flew him to get pictures on orders

he had, and he, in turn flew me to take pictures of property I had for

sale.

My show business contacts were of some help to me as a realtor. For

example, Buster Keaton asked me to find him a home in the Valley. I was

then on the San Fernando Valley Realty Board, with access to all the good

buys. I came up with two or three places I though he might like, and he

bought the first one I showed him. It was about a year old, spacious and

on two acres of walnut grove land. It had several nice out-buildings --

a large barn, a tool house, and a workshop. The original builder had split

up with his wife and the place was sold at a bargain.

At that time, Buster was on his way to a comeback after a long slump

in his career. The estate was well kept and he got interested in farming

the place. He bought some machinery and became a good do-it-yourself farmer,

with the aid of his ever-present Saint Bernard dog, Elmer. He had four

Elmers over the years.)

He liked bridge and poker, and one could get a card game there at the

drop of a hat. He had a miniature train rigged up from the kitchen with

tracks running up, over and around the rooms from the kitchen to the den.

He would send it off with a message in the engine cab for the cook for

sandwiches or beer. It was quite a kick to hear the little train huffing,

puffing, and whistling its way to the kitchen.

Buster became interested in real estate as an investment, and I scouted

up several pieces of property for him that paid off handsomely. He was

interested in land and old homes that could be refurbished and rented.

He would drop into my office occasionally just to find out what was going

on in the Valley, and talk sports, especially baseball.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()