Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webzines in Archive |

Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webzines in Archive |

|

with Jad-bal-ja the Golden Lion: The Morphology of a Folktale by Edgar Rice Burroughs By David Arthur Adams [First published in the Burroughs Bulletin #41, Winter 2000) Ref: The Tarzan Twins in eText |

ForewordTarzan and the Tarzan Twins with Jad-bal-ja the Golden Lion is a very interesting story. It is the second of two folk,wondertales written about Dick and Doc, the so called “Tarzan Twins.” This story along with it’s predecessor,The Tarzan Twins, were written specifically for an audience of children rather than for adults, as the rest of the 24 Tarzan novels certainly were.

Edgar Rice Burroughs is recognized as being a great story teller, in fact, this is one critical point about his writing that is agreed upon without question. Since ERB wrote at least these two stories specifically for children, I thought it be interesting to see if these tales fall within the typical structures of the folktale or fairy tale as outlined by academic folklorists.

A great deal has been written about the folktale in general, especially about a popular branch of this genre, the fairy tale, or the wondertale, as it is classified by folklorists. The study of this type of literature is an important academic area that falls under the headings of anthropology, folklore, and linguistics. In fact, so many studies have been written about folklore alone that to fully understand it all would take a lifetime of specialized concentration.

Scholars who collect the thousands of folktales throughout the world have developed many systems of classifications for these stores. Antti Aarne, the great Finnish folklorist, even constructed an index for the classification of folktales that attempts a scientific method akin to ones used by biologists in labeling flora and fauna.

This article concerns itself with but one of these many works called the Morphology of the Folktale by the great, Russian folklorist, Vladimir Propp (1895-1970) which first appeared in an English translation in 1958. It is not my intent to argue the validity of Propp’s theories since this article is meant for a popular audience more interested in the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs rather than arcane studies on the folktale. The interesting thing about Propp’s work is the fact that he developed a method to study the folktale according to the functions of its dramatis personae. He claims that these “functions” or acts of a character are limited in number and follow a more or less identical sequence. This outline can easily be applied to the Tarzan Twins stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

The word “morphology” simply means the study of forms -- the study of component parts in their relationships to each other and to the whole -- in other words, the study of the story’s structure. An application of Propp’s list of “functions” to Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins with Jad-bal-ja the Golden Lion reveals that this story does indeed follow the system to a remarkable degree, as you will see in the following analysis. Perhaps this formal study may reveal some of the reasons why Burroughs, was such a great natural storyteller.

A Morphological Study of Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins and the Golden Lion According to Propp’s “Functions of Dramatis Personae”

[The numbered items are Propp’s “functions”. The small case explanations which sometimes immediately follow the functions are also Propp’s own words.]

I. One of the members of a family absents himself from home.

Sometimes members of the younger generation absent themselves, or they go visiting.Dick and Doc, the twin heroes of this story, are on a visit to Africa staying with Tarzan, a distant relative of Dick’s father. Since this is also the situation in the earlier tale,Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins, the actual absentation of the story occurs when Tarzan leaves the boys in the jungle when he goes off to investigate a danger he senses ahead. This separation is made complete by a thunderstorm that erases their trail from the ape-man when they decide to move away from the place Tarzan left them.

II. An interdiction (a warning) is addressed to the hero.

In chapter one the boys are introduced to Jad-bal-ja, Tarzan’s golden lion. Tarzan tells the lion that the boys are his friends and not to harm them. He warns the boys not to touch the lion unless he comes to them and rubs his head against them. However, the true interdiction comes when Tarzan’s warns the boys to remain with the lion when he leaves them in chapter two.

III. The interdiction is violated, and a villain enters the tale.

The boys become afraid of the lion and climb into the trees. After the storm they leave the place in the jungle where Tarzan left them in the care of the lion. This act violates Tarzan's interdiction.In chapter three the villains are introduced -- the 20 frightful men. They are outcasts from Opar, followers of Cadj, the wicked High Priest, who had overthrown La, the true High Priestess of Opar. (Cadj was killed by Jad in an earlier novel, Tarzan and the Golden Lion , and La was restored as a reformed, peaceful queen.)

IV. The villain makes an attempt at reconnaissance.

The leader of this villainous band is called, Glum, the self-appointed High Priest of the Flaming God. They are all true believers seeking a place to build a new temple to their God, the sun. Under Tarzan’s orders La has given up the practice of human sacrifice at Opar, but these beast-men are anxious to find a location for a new temple and a victim so they may continue their old time religion. If they do not find someone soon they may even have to sacrifice one of their own.With this fetid pack of ape-like men is a lovely little white girl with golden hair. One of the hideous twenty, Blk, has a place in mind for the new temple, and the captive little girl is planned to be their new high priestess. She is the victim that the heroes must try to rescue.

V. The villain receives information about his victim.

Another member of these renegade priests of Opar is Ulp, a rather dull-witted character who suggests sacrificing the girl, and is struck down by Glum. Glum tells him that if they do not find someone soon that he, Ulp, will be the sacrifice.The little girl has been traveling with the 20 hideous men for two months. They have not harmed her because their Flaming God only accepts sacrifices at the hands of a woman, and she is the chosen one. They named her Kla, meaning New La. She is unhappy but strong.

VI. The villain attempts to deceive his victim in order to take possession of him or of his belongings.

[Propp’s outline of functions allows that elements peculiar to the middle of the tale to be transferred to the beginning. This is the case for the next two functions, VI and VII. The following events do not happen until chapter seven in Burroughs’ tale.]Ulp is the girl’s guard. He is fretting that he will be sacrificed by Glum. He reasons that if the girl were gone there would be no high priestess to offer a sacrifice.

A lion roars, and Ulp hopes it will come and eat the girl. He pretends to save her by leading her from a hole in the back of the shelter into the forest, but he leaves her beneath a large tree for the lion.

VII. The victim submits to deception and thereby unwittingly helps his enemy.

When Ulp approaches Kla he says, “Do not be afraid,” the very words Tarzan will say to her at the end of the story. Ulp is an example of what Propp calls a “false hero.”Ulp uses the excuse that he hates Glum because he threatened to sacrifice him, and the girl believes him and follows him into the jungle to the danger that is resolved in its normal place in function XVI. The hero and the villain join in direct combat.

[The remainder of ERB’s tale falls within Propp’s outline without a transfer of elements.]

VIII. The villain causes harm or injury to a member of a family.

This function is exceptionally important, since by means of it the actual movement of the tale is created. Each of the earlier functions prepare the way for this function, create its possibility of occurrence, or simply facilitate its happening. Therefore, the first seven functions may be regarded as the preparatory part of the tale, whereas the complication is begun by an act of villainy. The forms of villainy are exceedingly varied.In this tale, the form is Propp’s example #8. The villain entices his victim. Ulp’s treacherous movement of the girl into the jungle marks the beginning of the actions of the heroes in a direct relationship with the victim.

IX. Misfortune or lack is made known; the hero is approached with a request or command; he is allowed to go or he is dispatched.

This function brings the hero into the tale. If a young girl is kidnapped, and disappears from the horizon of her father, and if Ivan goes off in search of her, then the hero of the tale is Ivan and not the kidnapped girl. Heroes of this type may be termed seekers.In the morning after the storm boys travel through the trees until they reach a game trail. They travel a short way on the ground, but Doc has a premonition of danger, so they return to the trees. From the view above they see the 20 frightful men hiding in ambush for them on either sides of the trail. Blk goes to reconnoiter, and finding nothing, the 20 step forth with the golden-haired girl, stunning the boys in the trees. “Who could she be?”

X. The seeker agrees to or decides upon counteraction.

A volitional decision, of course, precedes the search.The boys decide to follow the band and rescue the girl if they have a chance. ERB comments on their noble blood and self-sacrificing nature comparing them to heroic men on the Titanic !

XI. The hero leaves home.

Unlike the first absence element, this one is marked with a search for a goal.The boys follow for hours, traveling through the trees easily until mid-afternoon when the beast-men stop and build a crude shelter for the girl.

XII. The hero is tested, interrogated, attacked, etc., which prepares the way for his receiving either a magical agent or helper.

The hungry boys decide to go off in search for food. Doc blazes a trail with his hunting knife so they can find their way back. He has clearly taken charge of the situation. The antelope that Doc is stalking is taken instead by one of the beast-men who is also out hunting. The “veneer of civilization” falls away from Doc, and he wants to kill the priest of the Flaming God with a well-placed arrow. A quiet word from Dick prevents the killing. Dick has another idea.

XIII. The hero reacts to the actions of the future donor.

He performs a service of some kind, such as showing mercy.They frighten the crooked man away by shooting arrows around him from different directions, and he leaves the antelope behind for the boys to eat. Dick and Doc have shown mercy to this man by employing deception to get what they want instead of killing him. Doc has gained the “magic agent” of the bow, which he uses to good effect later in the tale combined with Dick’s idea for the use of deception, which actually becomes a form of terrorism.

XIV. The hero acquires the use of a magical agent.

This may be a capacity, such as the power of transformation into animals, etc., or an agent is eaten or drunk.After some misgivings, the boys eat the raw meat of the antelope. Thus, they become more like Tarzan.

XV. The hero is transferred, delivered, or led to the whereabouts of an object of search.

Generally the object of search is located in “another” or “different” kingdom. This kingdom may lie far away horizontally, or else very high up or deep down vertically. He may fly through the air or find a stairway or underground passageway.The boys return to the gorilla-men’s camp and watch them cook meat around a warm fire as they shiver in the trees in the night air. The tree they have chosen to climb turns out to be fortuitous for their deliverance of the object of their search, the little white girl.

XVI. The hero and the villain join in direct combat.

In humorous tales the fight itself sometimes does not occur. The hero and the villain may engage in a competition . The hero wins with the help of cleverness.This is the continuation of the story after functions V I and VII discussed above.

The boys hearing the same lion have hidden in the very tree under which Ulp has abandoned the little girl. They drag her screaming into their tree in time to save her from the lion. Ulp, hearing her screams, thinks the lion has killed her.

Ulp awakens Glum and tells him that the Flaming God has taken the girl away. He says that the light was so bright that it blinded him. He also tells Glum that the Flaming God left the message that there should be no sacrifices at the new temple until the god should come again in person to demand them. Glum checks the hole in the back of the shelter and believes Ulp’s story.

XVII. The hero is branded.

The boys are not even scratched by the lion, so the mark in this tale might be considered a psychological one because the girl laughs at them for being lost and has to help them find food, a breakfast of fruit, roots, and bird’s eggs. They are marked as comic heroes in this folk tale genre.

XVIII. The villain is defeated.

Glum’s murderous intentions are defeated for the present.

XIX. The initial misfortune or lack is liquidated.

Gretchen is saved for now. She is with the boys instead of with the beast-men, so her initial misfortune is over.

XX. The hero returns.

Sometimes return has the nature of fleeing.In the morning, Glum and the lesser priests continue their journey to the new temple site. Glum begins to doubt Ulp’s story.

The boys and Gretchen are moving slowly through the trees due to her inexperience. (She tells them that she would have had to kill people for sacrifices had they not saved her.) They descend to the ground to make better time away from the dangerous situation. However, during the night, they have made a complete circle in the trees, so they are actually traveling behind the beast-men but in the same direction.

XXI. The hero is pursued.

Doc decides to drop behind to tighten his spear head with grass. Dick and Gretchen are captured by the 20 frightful men. Dick calls back to Doc telling him to take to the trees. Glum sends a half dozen of the band to capture Doc, but he shoots one of them through the chest with an arrow.

XXII. Rescue of the hero from pursuit.

From this point onward, the development of the narrative proceeds differently, and the tale gives new functions.Glum moves toward the new temple site led by Blk bringing the captives, Gretchen and Dick, along. Gretchen urges Dick to escape, but he will not leave her.

Doc follows the frightful men, picking off one of them in the back of the pack with another arrow. Glum accuses Ulp of lying about the night visit of the Flaming God, but he is appeased temporarily. However, he makes Ulp walk last in line.

XXIII. The hero, unrecognized, arrives home or in another country.

Sometimes the initial villainy is repeated, sometimes in the same forms as in the beginning.The frightful men arrive at rocky hills and enter a ravine. Doc follows hidden high among the boulders.

XXIV. A false hero presents unfounded claims.

A special case . . . not found in every story.Ulp, who has been previous identified as the false hero, does not make any more unfounded claims, yet at this point of the story he is killed by Doc.

XXV. A difficult task is proposed to the hero.

These ordeals are so varied that each would need a special designation.Doc kills Ulp with an arrow, and Glum is furious to loose his intended sacrifice. Glum chooses Dick for an alternate sacrifice just as Doc shoots an arrow into his leg. Doc shouts down to Dick and Gretchen telling them not to give up hope and to watch for him after dark. Doc then kills another priest.

Glum sends six of his followers up the hill to capture Doc, but he rolls a boulder down, killing one of them. He tries to hold off the other five with stones, but they climb toward him. Doc kills another one with an arrow, then escapes into the forest on the other side of the hogback.

XXVI. The task is resolved.

Doc has beaten the hairy men for now. The four remaining men decide to return and kill Glum. Doc again follows, determined to rescue Dick and Gretchen.The frightful men arrive at the new temple site, a circular, natural, rockbound amphitheater. Glum tells the lesser priests to gather stones and raise an altar.

XXVII. The hero is recognized.

This may be a special mark or a simple recognition of accomplishments.Dick is proud of Doc’s heroism. He tells Gretchen, “Well, good old Doc made them sit up and take notice. If I have to die, at least I shall have that memory to console me.”

XXVIII. The false hero or villain is exposed.

Sometimes all the events are recounted from the very beginning in the form of a tale.Glum offers a long prayer to the Flaming God in dedication of the new temple, then orders an altar to be built of stones. From his viewpoint, his religious goals are about to be met after many difficulties. The altar is quickly finished; Dick is laid thereupon, and Glum tells Gretchen she must kill him with a knife upon his signal. Gretchen tells Dick that Glum will kill her if she does not do her duty. Dick says he will gladly give his life to save hers. Gretchen closes her eyes and raises the knife.

XXIX. The hero is given a new appearance.

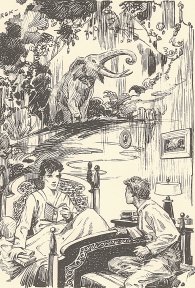

Transfiguration. Sometimes a change of dress.Doc, still following while gathering arrows from the bodies of those he has killed, gets a fright when he turns to see a lion standing five feet away. It turns out to be Jad-bal-ja the Golden Lion.

Doc places his hand upon the beast’s mane and buries his face in the great black collar, sobbing. Thus, the interdiction of Propps’ function number II is resolved. Burroughs notes the event with a flash of Doc’s memory.

“Like a title flashed upon a screen, a sentence burned suddenly bright in Doc’s memory: "Do not touch him unless he comes and rubs his head against you.”

It is a Burroughsian moment of transfiguration. Doc, the hero is united with Jad-bal-ja, the ultimate hero of the tale. Of course, Dick’s noble gesture of offering his life to save Gretchen is another such moment of transfiguring heroism.

Doc and the lion go the the rescue together, Jad bounding ahead.

XXX. The villain is punished.

In parallel with this we sometimes have a magnanimous pardon. Usually only the villain of the second move and the false hero are punished, while the first villain is punished only in those cases in which a battle and pursuit are absent from the story.Before Gretchen kills Dick, Jad arrives and bites Glum’s face off. Tarzan calls Jad from the top of the escarpment telling him to stop the killing. He orders the lesser priests, who are running away, to come back to the altar.

Doc arrives on the scene and says, “Gee, we are all saved, aren’t we?” Tarzan holds Gretchen in his arms and says, “Do not be afraid.”

Tarzan tells the lesser priests to return to Opar and be loyal to La. They agree to do so.

XXXI. The hero is married and ascends the throne.

Tarzan returns Gretchen to her father at the forest camp. “Don’t thank us,” says Dick, “Thank Jad-bal-ja, the golden lion, for after all it was he who really saved Gretchen.”An interesting twist to this tale is the fact that Jad-bal-ja is given credit for the final rescue befitting the title of the story. The hero does not marry the heroine, but Propp notes that “by no means do all tales give evidence of all functions.”

Afterword

I have applied Propp’s functions to The Tarzan Twins, and found that they also work with that other children’s tale remarkable well. Also, the application of Propp’s method to the short stories in Burroughs’ Jungle Tales of Tarzan reveals that not only do Propp’s functions fit these tales, but they also uncover some interesting new aspects in the fundamental structure of these stories.I have found Propp’s functions to be an enlightening method of structural analysis and a particularly fruitful one for dealing with the typical folktale structures in both of the “Tarzan Twins” tales. Burroughs was able to create perfect fairy tales with apparent ease, which may explain at least in part his fame as a “natural storyteller.”

Burroughs, Edgar Rice. Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins, Canaveral Press, 1963.

Bibliography

Propp, V., Morphology of the Folktale, University of Texas Press, 1990.

For more Tarzan Twins art see ERB C.H.A.S.E.R. at:

www.erbzine.com/mag4/0498.html