CHAPTER VI: SWINGING INTO

HOLLYWOOD

All my life's plans were changed in the middle of the second semester

by a phone call from Tom Scully, a friend in Hollywood. He said there was

going to be a big party at the Edgar Rice Burroughs Ranch, given by his

daughter, Joan. "How would you like to attend?" he asked. "I would be thrilled."

I replied. Tom was dating a girl who was a close friend of Joan's from

their days at a private girls' school. It seems they had more women for

the party than men and warned to square the odds.

This Burroughs Ranch, some 560

acres, was famous because it was first owned by General Gray Otis, publisher

of the Los Angeles Times. His Spanish ranch house had a ballroom, stables,

and a pool, which in those days was still a novelty. It was on a hilltop

overlooking the entire San Fernando Valley and extended from Ventura Boulevard

to Mulholland Drive. There was no town or designation other than the Tarzan

Ranch, named for Burroughs' most famous creation. The post office was Marian,

which later became Reseda. The town of

Tarzana developed hears later.

I arrived at the ranch with Tom in my "Whoopie," Model T. I was thrilled

to meet Mr. Burroughs, in my opinion the world's greatest fiction writer.

We were all swimming, so I was in trunks when Joan took me over to meet

him. He watched the festivities with interest and chatted with all the

guests. I also met Mrs. Burroughs and their two sons, Hulbert and Jack.

Hulbert was a teenager and Jack was about ten or twelve.

The party lasted on into the evening with food and dancing, though no

drinking. I danced several times with Joan, who was eighteen then and seemed

terribly sweet and lovely. These girls attended the best private schools

in and around Los Angeles since they were daughters of bankers, lawyers

and tycoons of all kinds.

It was a fine chance to see how sons and daughters of top society in

Los Angeles amused themselves, and a long distance in more ways than mileage

from t he beach picnics I was used to. When I left, my beat up Model T,

brought around by a parking attendant, was followed by a beautiful Packard

Twin-Six driven by a chauffeur.

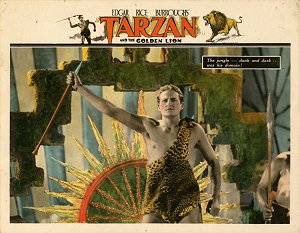

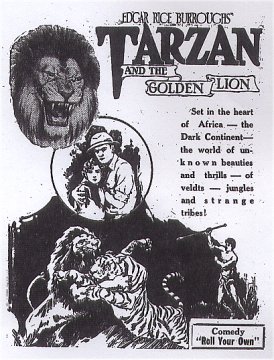

About two weeks later, I received a phone call from the Film Booking

Office (FBO) casting director. He said, "We are in search of a man to play

the lead in an upcoming production of Tarzan and the Golden Lion

and that Mr. Burroughs thought you would be a good bet." About fifty screen

tests of musclemen and all kinds of athletes had proven unsatisfactory.

(Mr. Burroughs then had a clause in his contracts to approve who played

Tarzan.)

The casting director raved about what a big picture it would be, but

I told him. "I have no aspirations to become a career actor. Thank you

very much." Meanwhile, Joan had heard about the studio wanting to make

a test and Mr. Burroughs had told her that he though I was ideal. In fact,

he told the studio that I came closer to his conception of Tarzan than

anyone he had ever seen. Joan put pressure on me to make the test, and

I finally said, "I will do that much to please you and your very gracious

father."

The next day the casting director called and said. "Mr. Burroughs called

and informed us you will make the test." The following Saturday they sent

a studio car to Glendale for me. The producer of this picture was Joseph

P. Kennedy, head of the Kennedy clan, father of John F. and Bobby. It was

to be a super production, with the largest budget the studio had ever allocated.

I was not a real actor and was worried about going before the cameras

for such an important project. It was a silent picture, so at least it

didn't take a Barrymore to grunt and point. The body was the gimmick in

this case. Joan and her father attended the test and were delighted at

what they saw. In a few days I was told, "You have the job." I replied,

"Even though I agree to take the test, I am not absolutely sure I want

to give up my law studies."

Joan invited me to the ranch again for a horseback ride and dinner.

The Burroughs family had individual mounts plus two or three extra horses

for guests. the entire family had a routine of early morning rides over

several picturesque trails winding over the ranch.

I was on the spot now since they were all excellent riders. Mr. Burroughs

had been in the U.S. Cavalry, and took great pains to teach the entire

family horsemanship. I could tell that they were anxious to see if I could

handle a horse.

I had been around farm horses and a few good saddle animals when I was

a kid and knew a lot more than their average drop-in guest. Also, during

the summer that I spent working on The

Yosemite Trail, I had a good chance to learn from the head wrangler

of the movie troupe, Pedro Leon. He had checked me out on the do's and

don't's of both. Western and English-style riding, how to handle single

and double reins and other things necessary to be a good horseman. He had

even taught me how to make jumps over ditches and fences. I spent

a lot of time around the corral and stable practicing riding.

Mr. Burroughs had a large, lively horse saddled up for me with a McClellan

saddle and double reins. I measured the stirrup with my arm for the correct

length, checked the cinch, and gathered up the double reins properly and

prepared to mount. The entire family, I sensed, was scrutinizing me intently.

I mad a beautiful mount, turned the horse around a couple of times to get

the feel of his mouth -- whether it was touch or tender -- and then backed

him up cowboy-style for several steps. Applause and bravos rang out from

t he family. Joan ran over to me and grabbed my hand. Literally, I had

gone backward, but she said, "You're in! You'll never know how much of

a step forward you just made with this family."

Later I found out many visiting dudes, who dressed the part and bragged

they had ridden bareback had made a mess of mounting, reining, and handling

the horse. Naturally, these people were never invited back to ride with

the family.

The main topic of conversation that day was the screen test and how

much it would mean to me and the picture if I starred . Sudden fame and

fortune had come to people with a lot less to offer than they seemed to

t think I had. The studio sent me a script and painted a beautiful picture

of my future in an accompanying letter.

By now I had finished the requirements for my permanent teacher's credentials,

and was told I would be hired for the next year. Two successful years and

license confirmation would result in tenure, meaning that if one kept his

nose clean and did a good job teaching, his job would be permanent until

time of retirement. This left me in a quandary. Should I continue teaching,

get my law degree, or chuck them both for the glamour of Hollywood? What

would Lillie Belle think and what would happen to our wonderful dreams?

I wrote her a long letter about the whole thing, and in a day or so

received a long distance phone call from her. It was much better news than

I had expected. She was so set on my becoming a lawyer. "Congratulations,

Jumbo darling," she said. "It will be a thrilling experience for you and

you can pick up your law studies if it doesn't work out. I'll always love

you," she continued, "no matter what. If you should knock 'em cold in Hollywood,

we can be married just the same as if you were a brilliant lawyer."

"You're beautiful, my dear," I replied. "Keep your fingers crossed and

hurry out to California as soon as you can."

I was really excited that she accepted the situation the way she did,

but that was the kind of a gal she was.

The character Tarzan naturally was a great part of the Burroughs' life

and they were dissatisfied with the films made by the three previous Tarzans.

It was not the actors' fault the way the scripts were written. None of

the stories had ever followed the books. With a high-budget, full-length

feature and Mr. Burroughs retaining script approval, which he had not done

in the past, great things were expected from Tarzan and the Golden Lion.

It was one of Mr. Burroughs' favorite stories.

My roommate, Charley Eash, Tom Scully, my good friend who introduced

me to Joan Burroughs, the Dewey sisters, the coaches and teachers at the

high school were all flabbergasted that I had been chosen and all said

I would be a fool not to grab it. I called the studio and told the casting

director that I'd take the job.

The picture was started around August and would not be finished in time

for me to hold the teaching job any longer. I had to tell the school principal

of the developments and tender my resignation. He said, "We will hate to

lose you as you have done a great job for us, but truthfully, if I were

in your shoes, I would not hesitate to take the job."

I went to the studio to see the casting director and sign the contract.

Sensing my naiveté, he said, "Jim, this picture is not estimated

to cost much more than the proposed budget, and I have been ordered to

cut down drastically on all actors' salaries. You are scheduled for $75

per week. If the picture is a hit, you will be given a five-year contract

starting at $350 per week and increased $350 per week each year of your

contract. Remember you are an unknown in the business." I had gone too

far to turn back now.

If the casting director wasn't lying, he at least was doing a great

job pulling my leg. I had visions of at least $500 per week to start. With

more Hollywood savvy, I would have gone to an agent as soon as I was offered

the job, and he would have negotiated a beautiful deal for me -- and himself.

This was my first experience with a man trained as a manipulative "con"

artist.

Once I signed the deal with the studio, publicity broke like wildfire.

I was all over the newspapers, Hollywood trade papers, and magazines, with

pictures and interviews. Publicity men spent days interviewing me, taking

photographs by the dozens. I really knew that I had been had. If I was

all that important, I should have ahd a hell of a lot more than $75 per

week.

It was some consolation, however, to know that with all this publicity

and a good picture behind me, I just might make out real well.

The casting director know so little about the Tarzan book that he spent

days trying to cast the role of Jad-bal-ja, which was actually the name

of the Golden Lion. Similarly, years later when Joan and Mr. Burroughs

were visiting a set where they were filming a Tarzan story, the scrip had

the lion named some screwy name, and Joan suggested they should call the

lion Numa.

"Numa, Numa -- why Numa? the producer asked, aghast.

"I don't want to seem facetious," she replied, "but that is Tarzan's

generic name for lion."

"Well, what do you know!" he murmured. "Numa it will be from now on."

Luckily it was the first day of shooting and the first scene the lion had

appeared in.

As soon as school was over, I moved to Hollywood and shared a bungalow

with Tom Scully, who was now a sales executive for Carnation Milk Company.

He owned a snappy Moon roadster and was now engaged to Marguerite Corwin,

Joan's best friend as I mentioned earlier. Wm. Corwin, Marguerite's father,

was head of a Los Angeles Investment Company, and had a mansion in Laurel

Canyon, Mr. and Mrs. Corwin were close friends of Mr. and Mrs. Burroughs,

and the families visited each week for bridge and a few snifters.

I had a standing invitation to the Sunday night dinners at the ranch

by now. Joan and I were beginning to get pretty serious even though I was

eight years older than she. She knew all about my engagement to Lillie

Belle, which didn't make her all too happy.

The picture finally got under way with long days and hard dangerous

work. I preferred to do all my own stunts even though there was a double

standing by.

During the filming, I visited Joan whenever time permitted. On one particular

Saturday night we drove to a nearby theatre in Reseda to see a movie. (We

were both movie buffs and tried to see at least one picture each week.)

On this trip I borrowed Tom Scully's car because my "Whoopie" needed new

transmission bands. A regular happening to the model "T".

On the way home in a pouring rain, I met a truck-trailer. The oncoming

lights blinded me, my windshield was drenched, and the trailer was swinging

from side to side and I could not see it. I passed the truck but the trailer

sideswiped me, knocking the car off the narrow two lane pavement onto a

soft shoulder of the road. The car flipped over and landed wheels up. Since

it was a roadster with a canvas top, I was mashed into the mud with a part

of the broken steering wheel stuck in my chest. I could not move and I

was scared the car would catch on fire. The fumes of gasoline almost choked

me.

It must have been five or ten minutes, which seemed forever, before

I heard a truck and some people talking in a foreign language. They turned

out to be Japanese on their way to the Grand Central Market with a truck

load of vegetables. (The San Fernando Valley in those days was one huge

vegetable garden and alfalfa field.) They managed to get the car off me.

There were no houses or phones and they were just about to load me into

the cab of their truck when a limousine pulled up. It was the Corwins,

and they recognized the car at once -- with its license number thirteen.

How about that?

Their chauffeur helped the Japanese load me into the back of the limousine.

I shall always remember and thank those Japanese men who saved my life.

I could not have lasted long under the car since my left lung was punctured

and I was bleeding from various cuts and bruises. (One newspaper, in fact,

reported I had "received probable fatal injuries.")

There was no emergency hospital closer than downtown Los Angeles near

the police station. We arrived there and first aid was given me. I had

them call Dr. Glenn English, a good friend from Indiana University, once

a very prominent movie star doctor, who sent me by ambulance to the Hollywood

Hospital at Sunset and Vermont. (Later both my children were born there.)

I was put in the emergency care ward, and he worked all night

with me. Because of my collapsed lung, air was coming out under the skin

of my chest and blowing me up like a balloon. I was swollen horribly from

my chest to the top of my head. He kept me under alternating hot packs

and ice packs until the swelling went down, and somehow inflated my collapsed

lung. The car was damaged considerably but not beyond restoration.

By Monday, the studio was in a panic. The picture was too far along

to cancel, so they closed it down for a few days to see what would

happen to me. I began to recover and had no broken bones or facial lacerations,

so they shot scenes I wasn't in and some long shots, using a double. Then

when I returned I was to do the medium shots and close-ups. I recovered

rapidly. Nothing much was lost, except the picture was now far over

schedule.

As soon as I was able to leave the hospital, I went to live at Dr. English's

home, so he could keep a close eye on me. My lung healed within three or

four weeks. What healed more slowly was my reputation. Word got around

that I had been drinking that Saturday night, though Joan and I had nothing

stronger than a chocolate soda at a drugstore.

The picture turned out fairly well. In fact, it was the only Tarzan

picture that ever followed the original story closely, mainly because Mr.

Burroughs had script supervision. He was so pleased that he wrote a friend

in late 1926 that he was convinced it was going to be the best Tarzan picture

of all and that I was destined for stardom.

Dorothy

Dunbar, who was a big name at that time, as a feature player and leading

lady, played Jane. She later married Max Baer, the world's heavyweight

champion boxer. Edna Murphy played the ingenue lead, and had a second love

interest in the story with Harold Goodwin. He became a good friend and

a frequent golf partner from that time on. Let me say that Edna and I had

eyes for each other right away.

Dorothy Dunbar

~ Harold Goodwind

and Buster Keaton

Boris Karloff was also in the picture, and because he did such a good

job, the director let him have all the liberty he wanted in making up as

different characters. He played a witch doctor, a native chief, and other

weird characters. Adding stature to the film was Lui Yu-ching, an eight-foot

giant from China who had once been a bodyguard of the emperor.

Moon Kwan and Lui Yu Ching

~

Boris Karlof

Edna Murphy and I warmed to each other, and a spark turned to a low

flame.

I continued to see Joan, though not as often as before. The whole family

like me but they were afraid that Joan was too young to have any idea of

marriage. We all agree to wait two years, until she was twenty. Our romance

was now pretty much up in the air, but Joan and I felt that if we were

serious enough, two years wouldn't make any difference anyway.

Edna was nearer

my age, but there was still Lillie Belle to think about. We kept in touch,

though she had met a chap from Holland, named Wm. Van Dyke and was going

steady with him, which made us about even in the dating game. His family

owned a large banking empire in Holland and Dutch possessions, such as

Java.

Edna was nearer

my age, but there was still Lillie Belle to think about. We kept in touch,

though she had met a chap from Holland, named Wm. Van Dyke and was going

steady with him, which made us about even in the dating game. His family

owned a large banking empire in Holland and Dutch possessions, such as

Java.

During one of their dates, they had a terrible automobile accident.

Lillie belle was seriously injured, broken bones, and internal injuries,

and spent months in the hospital having many operations. Van Dyke, who

was not too badly injured, stayed by her side. This came as a shock to

me, but I could not get away to see her because I was in the middle of

the picture.

Several weeks later, she was brought out to Los Angeles' Good Samaritan

Hospital to see a specialist because the accident had almost destroyed

her hearing. I had a chance to visit her in the hospital, but it was a

sad reunion. I had to write notes since she could not hear my voice. We

broke down emotionally, but finally she made it clear that we should break

our engagement because she might be crippled for life and be a burden to

me and my career.

When I left, she gave me a loving kiss and wrote a note asking me to

walk out of her life without looking back. She also said, "I'll love you

forever, Jumbo." It was a terrifying jolt, but she had made up her mind.

In a few years, I received an announcement from Amsterdam that she and

Van Dyke were to be married. Her hearing had improved and she was in pretty

good shape again. I heard from her on Christmas every year after that for

many years. There was always an affectionate note wishing success and happiness.

When Hitler invaded Holland, she and her husband's family escaped to Java

and remained there for the duration.

Tarzan

and the Golden Lion hit a terrible market because "talkies" were coming

in and this was the last silent Tarzan feature, though there were later

silent serials. The studio considered dubbing in the sound-voice over the

film and adding sound effects, but gave it up as too expensive. It was

released in early 1927 in six reels.

Tarzan

and the Golden Lion hit a terrible market because "talkies" were coming

in and this was the last silent Tarzan feature, though there were later

silent serials. The studio considered dubbing in the sound-voice over the

film and adding sound effects, but gave it up as too expensive. It was

released in early 1927 in six reels.

Naturally, it was not a smash hit although it did well under the circumstances.

The major chain houses had to turn it down as they were equipped for sound.

However, many small towns and independent theatres had not yet wired up

for sound, due to the great expense, and continued to screen silent films

for two or three years after talkies. The picture proved to be a big hit

on the B circuit. The picture mad a good profit as it was a super-special

for the smaller houses.

A fresh evalualtion of the film today seems impossible as there was

no known print in existence as of 1974. It may have been destroyed when

the studios switched from nitrate to acetate film. Nitrate film was highly

volatile and inflammable. One print might just be deteriorating slowly

in some film archive.

Some years ago,

I wrote Mr. Joseph P. Kennedy, asking if it were possible that he had saved

a copy of the picture. It was just at the time when he had the misfortune

of a stroke. His secretary wrote me a very nice letter explaining what

had happened and that he was not able to answer me. I contacted Edward

Kennedy U.S. Senator, in 1973, hoping he could give me an idea about the

existence of the film. He was very kind to answer, but that he did not

know of a print. He also said he would try and find out if there was a

copy somewhere in the Kennedy archives. So far, I have had no word. I did

hear recently that t here was a copy kicking around in Australia.

We are now seeking more information on this rumour.

Some years ago,

I wrote Mr. Joseph P. Kennedy, asking if it were possible that he had saved

a copy of the picture. It was just at the time when he had the misfortune

of a stroke. His secretary wrote me a very nice letter explaining what

had happened and that he was not able to answer me. I contacted Edward

Kennedy U.S. Senator, in 1973, hoping he could give me an idea about the

existence of the film. He was very kind to answer, but that he did not

know of a print. He also said he would try and find out if there was a

copy somewhere in the Kennedy archives. So far, I have had no word. I did

hear recently that t here was a copy kicking around in Australia.

We are now seeking more information on this rumour.

I have a note, dated 5 February 1976, which reads as follows:

Richard Lamparsky, author of Where Are They Now, recently interviewed

me. I mentioned my plight in trying to locate a copy of Tarzan and the

Golden Lion. He said he would try to help me out. In a week or so,

I received the following note: "I thought you would like to know that your

Tarzan film does indeed exist. It is owned by The American Film Institute,

J.F.K. Center, Washington, D.C." I have written them a letter asking

for a print, but as of this date, I have received no reply.

A long dry spell hit me after the picture was completed. I found that

I was typed as Tarzan -- that I could lift an elephant, but could not spell

it, that I was half human and half ape. The studio people had never bothered

to read the real story that Tarzan was a highly-bred English nobleman.

Their impressions were from the faked Tarzan scripts that had never followed

the book.

It became so ridiculous that a well-known producer turned me down for

a good part in a football story, saying, "You played Tarzan -- the audience

wouldn't believe that a half ape could play football."

The studio did not renew my contract after the picture. I was not unhappy

about this as I was disgusted at the salary they were paying me. The rumor

also persisted that I was unreliable because of the accident I had while

Tarzan

the Golden Lion was in production.

Naturally my ego was deflated and I had to scrounge for jobs on my own.

I had no agent. Edna believed in me, however, and our romance continued

to build. We attended many Hollywood social events - the tame ones -- we

did not drink, unlike many Hollywood people.

Edna lived with her father in a modest Hollywood bungalow. He was a

fine Irish gentleman and both were devout Catholics. I attended church

regularly with Edna and found it inspiring. As Edna was strikingly beautiful,

she was a popular leading lady and had all the work she could handle.

My career slowed down to a halt as the studios became filled with short

stars and leading me, such as James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, George Raft,

Edward G. Robinson, Paul Muni and John Barrymore.

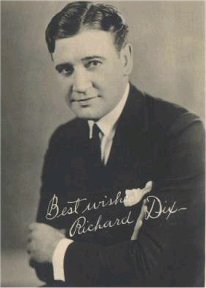

There were a few husky stars, and I managed to hustle some jobs

with taller actors. I met Monte Blue at several Shrine activities, and

he gave me two or three jobs in his pictures. Fred Thomson, the Western

star, was also a big fellow, as was Tom Tyler. I played in many of Richard

Dix's pictures, sometimes standing in a hole to hide the difference in

our heights. When my son, Mike, was born, he visited the hospital and brought

Joan a bouquet of red roses. We became very good friends.

I still couldn't get an agent because of that rumor of drunkenness,

which I couldn't break down at the casting offices. I always had callbacks,

however, from the studios and stars where I did work. In jobs with smaller

stars, I would usually be seated as a sheriff or judge. Tex Ritter, who

came along about that time, was a pretty tall guy, so I made three or four

Westerns with him. They were all made on location but were typical shoot

'em up -- shoot your pony and ride your pistol, we called them.

On one occasion, we made two low-budget, five-reeler Westerns simultaneously.

Ten reels in ten days. On each camera setup we would do a scene for one

picture, change clothes, positions and horses, then recite different dialogue

-- all without moving the camera. It felt strange making two pictures at

once, and they weren't too hot, but like all quickies, they got by.

Fred Thomson and I got acquainted during the Tarzan picture since he

also worked at the FBO studio. He thought I would do well in his pictures

because of my size, so he cast me as his brother Frank, in a big production

of Jesse James.

Fred was an Olympic athlete, a graduate of Occidental College and Princeton

University, and an ordained Presbyterian minister. He was a chaplain in

World War I, with many citations for his work at the front under heavy

fire. He visited our set many times while I was playing Tarzan and we struck

up a friendship. He was producing his own pictures and arranging the financing.

He had married Frances Marion, one of the leading scenario and script writers

of that time.

When word got around that I was to play Frank James, he received a telegram

from a distributor advising him not to use me. The telegram, which he showed

me read: "Advise you not to use Jim Pierce in your picture, as a foolish

accident caused the studio a long delay in the Tarzan picture and cost

the studio a lot of money."

I told Fred it was all untrue. I said, "It was not a foolish accident.

It just happened."

"I didn't believe it in the first place," he said. I had to be sure

because the releasing company brought it up."

I was excited over this job, which offered an excellent part at $350

a week, quite a boost from my salary as Tarzan. We went on location in

Bridgeport, California, Flagstaff, Arizona, and many ot her places. Frances

Marion visited the location, bringing with her Mrs. Laurence Stallings,

wife of the author. Stallings was one of the better screen writers.

Jesse James featured a Civil War sequence as well as all the

later exploits of the James Brothers. ONe of these episodes wa about the

Quantrill raiders, a guerrilla band whom the James boys joined. In a giant

battle scene, we were to charge down a hill, fighting the regular army.

The special effects department had placed charges of dynamite to go off

at intervals as we were riding and shooting.

The remote control operator, who pushed all the buttons and switches,

accidentally switched one at the wrong time just in front of my horse.

I was almost over it when it exploded and I went right through it.

My horse fell and both of us went sprawling. It made a terrific albeit

unplanned scene. I was not hurt and neither was the horse, but a second

earlier and we would have been blown to piece. I caught the horse, mounted

and rode like mad to catch the rest of the gang, which thundered ahead.

The picture had sound effects but no dialogue. Shooting took about twelve

weeks, so I did pretty well at $350 a week.

During

the location in Flagstaff, Joan and Mr. Burroughs drove up to visit me

on their way to visit the Grand Canyon. They stayed there two or three

days and watched us work.

During

the location in Flagstaff, Joan and Mr. Burroughs drove up to visit me

on their way to visit the Grand Canyon. They stayed there two or three

days and watched us work.

Jesse James

was a hit, and after that I made several pictures with Fred Thomson, always

playing heavies. In these pictures, Fred liked to have a large adversary

for the barroom brawls. It would look ridiculous for a star to beat up

a little shrimp.

In one of these pictures -- I believe it was Kit

Carson -- we were on location and Fred felt ill, but finished the

picture. He went to the hospital for a checkup and they operated almost

immediately. Despite his great physique, he died on Christmas Day, 1928.

According to Frances Marion's recent autobiography, Off With Their Heads!,

he

had stepped on a rusty nail.

Fred Thomson deserves a lot of credit. He was the first to use the camera

truck for running alongside actors on horseback for close-up and medium

shots. He had a mechanized rig built out to the side or rear of the camera

truck that showed only the head and shoulders of the actor or actors riding

along. It was called a balloon tire shot. The mechanical apparatus simulated

horseback riding.

Also, he was the first to use the gold leaf reflector that softened

the face and eyes of the actors in close-up scenes. The bright silver sun

reflectors caused Fred's eyes to squint, because there was something in

their coloration that the silver was too strong for. The gold soft reflector

cured that, and is still used extensively today to soften the face and

eyes, like the baby blue shot used in stage lighting.

He was a great student of pictures and knew almost as much about cameras

as the head cameraman, devising several techniques for camera operations

and certain types of lenses and attachments. He was also a stickler for

historical authenticity.

Those were the days before unions and everyone, including actors, pitched

in to help the crew. We carried cameras, moved props, and held reflectors

from first sunlight in t he morning until late in the evening. We chased

the sun as long as we could and shot until it went below the horizon.

We got no overtime and there were no laws to prevent this. Today there

is a special union for each branch of movies in the production department,

so an actor would never be allowed to lend a hand in anything pertaining

to the crafts, electricians, painters, carpenters, grips, or cameramen.

Neither can one craft help another. That became pretty expensive and contributed

to the rise of runaway productions outside of Hollywood.

Then a cowboy would get five dollars a day, bring his horse and lunch,

and do stunts at the same time. ONe day I noticed cowboy behind a set running

his horse and taking falls just for practice. today it would be several

hundred dollars a fall because the cowboy would belong to a union. Unions

were a good thing generally, though, because there were a lot of unfair

practices by the producers and studios.

Edna and I continued our romance. In fact, we went to a priest to discuss

Catholic marriage requirements.

I was scheduled to go to New York to meet the rest of her relatives.

There was no date set and we had not absolutely decided to get married,

but we were making tentative preparations. Edna was in New York on a picture,

and I was to meet her there.

On the way, I stopped in Shelbyville, Indiana, to discuss the situation

with my family. My father said, "This situation calls for some serious

talk. I have never interfered with any of your plans, neither have I tried

to influence you against your will. However, I now feel I should try to

give you some fatherly advice."

"Marriage, at this point, would be very risky," he continued. "You are

not a huge success as an actor, and coaching now has gone by the boards.

You not only owe it to yourself to be established in a career, but, more

importantly, you should not take a chance of also wrecking Edna's happiness."

After a period of silence, I turned to mother, and said, "What do you

think, Mom?"

"Hubert, my dear," she replied, "I would hate to see you rush into something

that might cause your great unhappiness later. Your father and I had such

a hard struggle for so many years, and there were times when we thought

we could not make it. Until you are firmly established as an actor, or

whatever, in case acting fails, I would say that you should wait."

"O.K.," I said. "Perhaps you are right, and I thank you for helping

me make a decision. I will phone Edna and tell her I feel we should wait."

That was the most difficult phone call I have ever made. I was so worried

about how I would tell her of my decision that I was hoping no one would

answer the phone. But no such luck. Edna happened to answer. "Hello, darling,"

I ventured, weakly.

"Jim - Jim, it's you," she said. "What's wrong? There is something,

isn't there?"

"Well -- er, ah, yes, I suppose you might say that!" I said.

"You are not coming to New York -- I'll bet that is it," she said in

a disappointed tone.

"You are right," I replied. "I have been doing a lot of thinking and

have decided it is not the right time to make our final decision."

"Why not? Why do you say that?" she asked.

"Well, I decided that since I am not really secure in the picture business,

I don't want to put you through the struggle and hardships that would follow

if I did not make a success," I answered.

"Perhaps you are right," she said. "I have been having some second thoughts

my self. I am rather successful and we could make out okay. However, I

know how uncomfortable that situation would be for you. I have seen too

many Hollywood marriages break up because the husband was not as successful

as his wife."

"I love you so very much, and am very disappointed," I continued. "If

we wait a little longer, perhaps the way will open. If it is right for

us to be together, we will be shown the way without a question of a doubt.

It's going to be forever, you know, if and when.

"That it is, my darling," she replied. "Forever and ever."

"I love you darling," I repeated. "Have a good visit and I will see

you soon in Hollywood. Goodbye, sweetheart."

After we returned to Hollywood, we saw each other frequently and went

to the usual parties and were still in love."

But after a few months, our paths gradually led in different directions.

We agreed to go out with different people. I began dating Joan again, and

Edna and Mervyn LeRoy started a heavy romance. She and Mervyn were married

soon thereafter.

The last time I saw her was years later after she had been divorced

from LeRoy. She was living at Malibu Beach with her sister. It was just

like old times and we were very happy to see each other again. Edna was

a beautiful and wonderful lady in every sense of the word. I am grateful

that I had the opportunity to have known such a wonderful person. She never

remarried.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()