CALIFORNIA, THERE I WENT

Glendale 1924-25

About June 1,

1923, I drove to Los Angeles to make plans to enter USC law school and

find a job. The trip was a trying experience because the roads were rough

and unimproved for long stretches. My little Model T fought bravely and

we managed to make Yuma the first night. Motels were rare then and were

called tourist cabins. Air conditioners were unheard of. Some hotels had

living and cooking arrangements, and I managed to find one with an icebox.

I had been told by people familiar with Yuma that one of the best ways

to fight the heat was to wet the sheets and put them in the icebox until

bedtime, then get under them with an electric fan running -- also a pretty

good way to catch pneumonia.

About June 1,

1923, I drove to Los Angeles to make plans to enter USC law school and

find a job. The trip was a trying experience because the roads were rough

and unimproved for long stretches. My little Model T fought bravely and

we managed to make Yuma the first night. Motels were rare then and were

called tourist cabins. Air conditioners were unheard of. Some hotels had

living and cooking arrangements, and I managed to find one with an icebox.

I had been told by people familiar with Yuma that one of the best ways

to fight the heat was to wet the sheets and put them in the icebox until

bedtime, then get under them with an electric fan running -- also a pretty

good way to catch pneumonia.

The sand dunes out of Yuma were impassable, so they made what was called

a corduroy road of railroad ties wired together and laid down over the

dunes, with frequent offsets for passing. The rule of the road was that

the one closest to the offset had to pull out or back up in order to let

the other pass.

The day I crossed, a blinding sandstorm blew up. Sand drifted over this

corduroy road until it was impossible to see the ties. A car that strayed

off them would sink into deep sand.

All I could do was wait it out. Most of the paint was sandblasted off

my car and the windshield was pitted. All travelers across the dunes were

warned to wait for the plow in case of drifted sand. It was like a snow

plow, pulled by mules, that scarped the sand off the ties. After four hours,

I saw the relief plow coming around the bend. I followed his trail and

was soon out of the dunes and on my way, rejoicing. Ordinarily, it took

twenty five hours to get from Tucson to Los Angles in those days.

On arrival, I prepared to enter law school and lined up the courses

I would need. My bachelor's degree was sufficient to qualify me as a full-fledged

applicant. Meantime, I stayed at the Los Angeles YMCA. It was located in

the middle of Los Angeles, not far from the USC campus, where the law school

building was just being completed.

One evening I received a call from Norman Hayhurst, an Arizona graduate

and head coach at Glendale High School, five or six miles out of Los Angeles.

It wa an incorporated city of a few thousand people, and commonly known

then as the bedroom of Los Angeles. Middle-class and working people commuted

to work daily on the Pacific Electric Railroad, which was the largest streetcar

system in the world before its destruction by the automobile and freeway

interests.

Glendale was a well-run city growing rapidly. It had just built a new

high school, Broadway High, and needed teachers and instructors of all

kinds.

I had met Hayhurst, the athletic director at Glendale in Tucson at a

homecoming event. He was quite a loyal alumnus and once a pretty good athlete

himself. He had asked "Pop" McKale for help in locating a coach, and McKale

had recommended me.

I was elated and soon met with the school board. The job was all set,

but there was one hitch. The State Board of Education had a strict rule

that all teachers had to pass an examination for a credential to teach

in any elementary or secondary school -- even though I could teach in a

university, such as Arizona.

It was impossible to go to law school full time and also get the courses

required for certification. Instead I settled for two night school courses

at USC while attending school three nights a week to prepare for the state

exam. It was a rigorous schedule, but I managed it. I passed the law classes

and got a temporary certificate to teach in Glendale. Another two years

of work was needed for a permanent certificate.

When high school opened in the new place, I was appointed head

line coach for football and head Class A basketball coach as well as teaching

three divisions in all sports, according to age, weight, and grade, so

that even the little guys in Class C got to play full schedules.

I roomed in a private home within walking distance of the high school,

but still needed my trusty Model T to travel to USC.

Lillie Belle had gone east for the summer to enter Smith college for

graduate work. Our plans hadn't changed, but I didn't see her until the

following summer when she came out to Santa Monica to spend her vacation.

We exchanged long letters of endearment and happy plans for our future

were still contemplated. She was convinced I would become a successful

barrister.

I became deeply involved in my athletic work. Hayburst, head coach of

Class A football, and I hit it off in great fashion. He had been a backfield

player and was not as experienced in line work as I. My line became exceptionally

strong and all my savvy was passed on effectively.

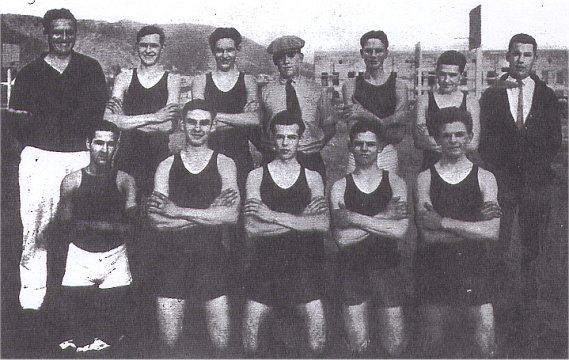

The team caught fire and we won game after game by a large margin. Glendale

High was suddenly on the map as the Dynamiters. We did not lose a game

all season and led the league. In the Southern Cal Championship playoffs,

we won all of our preliminary games and beat Compton in the final game,

26-0.

The annual of Glendale High School, the Stylus, said in 1925 that my

coaching "was a large factor in producing a winning team. It was

he who polished the rough edges of the line and put the team in fighting

form."

Law was still my ultimate goal despite the fact that I could have had

a lot of good coaching jobs in Southern California. I had several offers

from colleges and universities around Los Angeles, but declined with thanks.

The days fell into a routine. I would return from night school around

11 p.m. and settle down to one or two hours of homework for the next night's

classes. I seldom got more than five or six hours sleep each night. My

grades were average but I never once became discouraged.

Later in the fall, our basketball team started with a tremendous handicap.

The gym was not completed and football ran long into the basketball season

because of the championship playoffs. We had to wait for the use of the

football field to practice outdoors.

The goal posts were removed and basketball goals were put up, but it

felt unnatural to play basketball on grass. The annual correctly surmised

that we might have won the championship with more practices. As it was,

we finished third in a field of six teams, winning 60% of our games.

I was rehired for the following year and entered USC summer school full-time.

My grades improved with extra time to study. I became especially interested

in criminal law and enjoyed preparing and trying cases in the moot court.

I became good enough as a defense lawyer that m instructor complimented

me several times on my performances. Some phases of the law bored me, though,

such as researching cases on dry subjects.

Life was not actually all work and no play, though. An old college buddy,

Charles Cash, looked me up. He was a typical "Joe College" while in school

and never seemed to plan more than one day ahead. He was a Sphinx Clubber

and a good friend, but he never took anything too seriously. He was broke

with no job in sight, but wasn't too worried about it. Feeling sorry for

him, I arranged for him to share my quarters. He was good company and had

a tremendous sense of humour. I checked around for a possible job for him

and located one at a land title search company.

Charley soon met a high school girl, Marian Dewey who had a sister attending

USC and also working part-time for a commercial art company. The sister,

Alice was sweet as a peach, though she didn't cling. I could easily have

become serious about her had it not been for all my dream castles with

Lillie Belle. We had many dates and almost every weekend there was some

sort of a picnic or beach party.

Fall opened with the usual football excitement. Several of the championship

teams were back and we had high hopes for another winner. Several good

men had come up from the "B" team and replaced those who had graduated.

The line was heavier and stronger, the backs fast and aggressive.

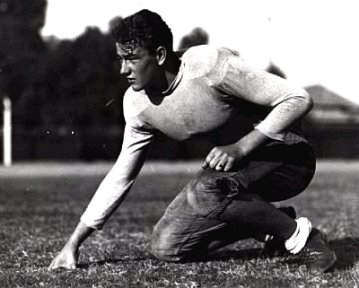

One of my linemen,

who was especially strong and aggressive was Marion Morrison. He played

guard and was really rough and tough, fit training for his later career

as John Wayne.

One of my linemen,

who was especially strong and aggressive was Marion Morrison. He played

guard and was really rough and tough, fit training for his later career

as John Wayne.

We started right off on the winning trail and reached the Southern California

Championship playoffs, but lost the final game to Long Beach in a bitter,

hard-fought battle. Basketball improved since we could practice inside

and had a better all-around team. We did not win the league, but finished

near the top.

During one summer hiatus from my coaching duties, I was cast in Temple

of Venus, a fantasy picture and sea story combined. The temple

was a large interior cavern in a cove along the shores of Santa Cruz Island.

The only other people there were some sheepherders and the people looking

after us and servicing us, catering and feeding us, and taking care of

the camp.

Centuries of tides and waves had cut out this fabulous cave area far

back into the mountains that came down the the water level, somewhat like

the Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, only on a smaller scale.

Venus, the goddess of gardens and spring, was to reign in the fantasy

episodes and later this same Venus played the female lead in the sea story.

Elaborate decorations were installed in these caverns under a terrible

handicap at great expense. All of this had to be done at a certain time

of day because when the tide came in, it filled up these caverns so it

was impossible to go any farther inside than the edge.

On the day for the shooting inside, there were to be huge fireworks

and a big display, a Walt Disney fairyland within this cavern. All was

ready for the prop men to bring in t eh fireworks. Everyone was in a big

rush to get the scene before the tide drove us out. In this great rush

and under pressure from the director, one of the prop men accidentally

fired a Roman candle, and it landed out of the scene where they ahd a lot

of extra fireworks piled.

Hell not only broke loose, but brought its own brimstone as the fireworks

exploded. It was many minutes before it stopped and the place was blanketed

with suffocating powder smoke. The decorations were destroyed and the set

ruined. Work .closed for the day amid much moaning and griping by the director

and the business managers.

Several days after shooting began, the studio told director Henry Otto

that the woman playing Venus would have to be replaced. This meant more

trouble because all her scenes had to be reshot. Jean Arthur was the one

they threw out of the picture because they said she couldn't act! How wrong

they were! Later she became one of Hollywood's biggest stars. A frail-looking

ingenue, named Mary Philbin, replaced her.

During the changeover, we worked on the sea story and I was in a gang of

poachers and renegades including William Boyd, Dave Butler, and Stanley

Blystone. Bill Boyd later became Hopalong Cassidy and David Butler one

of Hollywood's finest directors and producers. The three of us roomed in

a cabin for weeks. Fog, rain, and had luck dogged us through this whole

location. My friendships with them stood me in good stead. In later years,

I got quite a bit of work from Dave Butler and appeared in some of the

"Hoppy" westerns.

Santa Cruz is a lonely island about fifty miles west of Santa Barbara.

There's nothing there but a cove, a sheep camp, and a narrow, sandy beach.

We had nothing to do after work but play poker, and there was a lot of

drinking. Booze was brought in by the supply boat that plied back and forth

each day from Santa Barbara. Prohibition was in force then and many booze

transactions were made at night in this small harbor. Speedboats

would meet the ships a little way out from the shore and run the booze

back to the mainland to smaller boats or boats anchored off Santa Barbara.

My working summer vacation ended soon enough for me to return to the

coaching and law school grind.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()