[14] L.D. Nichols. 1867. Sam's Monkey. Our Young Folks.

An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls, 3(3): 175-185 [A monkey

wreaks havoc in the Sumner household]

Dora Sumner was a dear little girl, about four years old. Her hair was

the color of corn-silk, and fell on her plump shoulders in soft flossy

curls, while her blue eyes looked lovingly at everybody and everything.

She was such a sunny-tempered little creature, that her old nurse Roxy

used to say, "Ten children like our Dora would make less noise and trouble

in a house than one like Master Sam." Sam was Dora's only brother, -- a

saucy, careless fellow of eight; always tearing his clothes, playing tricks,

chasing the cat, or teasing Annie. As for Annie, she was the eldest of

the children, a gentle, thoughtful girl, who rather liked to be considered

a young lady, though she was not much over ten.

One evening in March, the three children were with their mother in the

cosey [sic] sitting-room of their house, in a pretty village near

Boston. Annie and Sam were playing dominoes, while Dora, who had finished

her early supper of bread and milk, was watching the game, and making brave

efforts to keep awake until papa should return from visiting his patients

and give her a good-night kiss. The poor child was very sleepy, however,

and, in spite of all her struggles, her rosy mouth stretched once and again

into a big yawn. Each time, her mother and Annie noticed it, and smiled

significantly, for it was one of the family rules that the third yawn after

tea should be a signal for going to bed. At last number three came, and

the little one, slipping from her chair, leaned her weary head on her mother's

lap, sighing, "Wing for Woxy, mamma. Do's 'awned fwee times." Roxy came

accordingly; but before she carried her pet away, good-night kisses must

be given all round, and the prayers said at the mother's knee. The other

children paused in their game to watch the child, as she knelt and slowly

repeated "Our Father," and "Now I lay me," then drew a long breath and

went on, "God bwess papa and mamma, Nannie and Sam and Woxy, make Do a

good girl, and bwess dear Uncle Max, and 'Genty Annie,' and bwing 'um safe

home out of the big sea. For Jesus' sake, Amen."

All the listeners knew what Dora's prayer meant; but perhaps you may

not understand it, and so I will tell you that "Uncle Max" was Mrs. Sumner's

only brother, -- a very warm-hearted, generous man, who, having no wife

or children of his own, was extremely fond of his sister and her family.

He was a sea-captain, and owned a fine vessel named the "Gentle Annie,"

in which he made voyages to China, South America, or the West Indies. Whenever

he returned from these trips, he brought presents for his sister and the

children in his big green chest. They all loved him dearly, -- he was so

merry, so good-natured, so willing to tell them stories, and sing them

songs, and amuse them in funny ways that no one else would have thought

of. Sam often declared that Uncle Max was better than Christmas, or New

Vear, or even Fourth of July; and once at school, when Jenny Dowse boasted

she had a pony all her own, and Susy Moody said she had two new silk dresses,

Annie had silenced them both by saying, "You haven't either of you an Uncle

Max, who owns a whole ship, and has been to China and seen whales and sharks."

This beloved uncle had left them six months before the evening I was

telling you about, intending to visit several South American ports, and

to touch at Cuba on his return. He was now expected daily; and, for a week

past, the children's first act in the morning had been to rush to the head

of the stairs to see if the well-known green chest were in the hall below.

One of Uncle Max's merry ways was to let them all wish for what they

wanted he should bring them next time. On the last afternoon he was with

them he would lie down on the sofa as if very weary, and declare his intention

of taking a nap, adding, that they must be very quiet, and, if they had

any last wishes to express, they might whisper them to "Gentle Annie."

By this he meant a little model of his vessel which stood on a table at

the head of the sofa. One of the sailors had made it for Sam. So the children

would keep as still as mice, until, from breathing heavier and louder,

Uncle Max would finally snore sonorously; then one by one they would steal

up, and whisper the secret wishes of their little hearts to the carved

figure-head of the "Gentle Annie." The elder ones always had their minds

made up, and their wish ready, having previously ascertained where their

uncle was going, and then consulted their parents and their geographies

as to the desirable articles to be procured there. Little Dora, however,

more ignorant, and more trustful, always said, "P'ese, Genty Annie, bwing

Do huffin nice." Somehow or other, the wishes were always gratified, and,

when next uncle's chest returned, there were the very things they had whispered

about.

Perhaps you are old and wise enough to guess the mystery; perhaps by

this time Sam and Annie had solved the puzzle; but the plan was first made

when they were so young as to think there must surely be fairies' work

about it, and no one had ever showed any wish to give it up. Both uncle

and children liked it as well as ever. Before the last voyage, Sam had

wished for a funny live monkey, Annie for a big basket of oranges, and

Dora, as usual, for "huffin nice." Sam had heard how lively and roguish

monkeys were, and he thought it would be rare fun to have one, and see

him playing tricks in the kitchen, putting neat Annie's basket out of order,

and perhaps even pulling off Roxy's false curls. Annie's idea had been

more amiable. "I might wish for a sandal-wood fan," she thought, "but I

could only carry it once in a great while to a party, and I know I should

fidget all the time then, for fear it would get broken. I will have oranges,

and then I can take one to school every day for luncheon, and papa loves

them cut up in sugar for tea, and I can ride about with him, and give them

to his patients. I will have the fan when I am older." So she wished for

the fruit, and Sam for Jocko; and when I tell you that part of the rule

was, that neither child should know the other's wish, you can understand

how eagerly they looked for their uncle's return, which would bring surprises

as well as gifts to all.

While I have been telling you all this about Uncle Max, Dora has gone

to sleep in her crib, the game of dominoes is ended, papa has returned,

tea is over, and Sam and Annie have also snuggled into their respective

beds. Just as they had called out "Good night" to each other for the third

time, the front gate was heard to click open and slam shut, and a clear,

strong voice came singing under the windows,--

"But give to me the swelling breeze,

And white waves heaving high."

"Hooray for Uncle Max," cried Sam; and his slim legs kicked off the blankets

and carried him to the head of the stairs in an instant.

"O splendid! O hush!" exclaimed Annie, in one breath. "O, where is

my wrapper?" -- and out she came too, thrusting her arms into the sleeves

of her flannel gown.

Sure enough, there is father opening the door, and mother, close behind,

slips past him, and is snatched in the big blue-coated arms. Yes, it is

darling Uncle Max! No one else has such shaggy hair, all in black curls

and rings; no one else such tanned cheeks. Who beside him would lift mamma

clear off her feet, and call her his "own dear Molly," or dare to take

papa by the shoulders and kiss him? Nobody else would have spied the shivering,

eager little peepers above, and, singing out so heartily, "Now for the

babies!." have come leaping up the stairs. Sam gave a shrill yell, and

rushed down three steps, and clung around his waist; and as he reached

the top, Annie, laughing and crying together, launched herself into his

open arms, and received a dozen kisses before she was set free.

"Go back to bed, you little foxes," cries the merry uncle. "Here comes

Roxy, and she'll scold us both. Go quickly to sleep, or you won't be fit

to go with me to the Museum to-morrow."

The children disappeared quickly in their rooms.

"Ah, Roxy, here I am again, to break all your good rules, you see."

"I'm merry glad to see you, Captain Max, whatever," says Roxy; "and

I know it's little Dora you'll have to kiss before you'll have your tea,

sir."

So she led the way, turned up the gas, and there lay the little cherub,

rosy and beautiful, in her crib, with her golden curls tossed like a glory

above her head. One fat hand clasped tightly a much-soiled rabbit, made

of once white cotton flannel, and with which the child always went to sleep.

The rough sailor gazed at her till the tears filled his eyes, and his sister

called from below, "Tea's all ready, Max."

"Ay, ay," he answered, kissed Dora gently, and went down.

You may be sure the children were all up early the next morning. Dora

rode down stairs on Uncle Max's shoulder, Sam and Annie following, full

of eager expectation. The first thing they saw on entering the dining-room

was a big wooden box marked "Miss Annie Sumner," full of delicious-looking

oranges, peeping out of their white papers. The next discovery was a box

of guava jelly in Dora's plate; then a piece of beautiful white and pink

Cuba linen for wrappers on the mother's chair, and, chained to the leg

of the table, a funny, old-mannish looking monkey, about as big as a young

cat. You can imagine the astonishment of the girls at Sam's gift, their

delight over their own, and the thanks and kisses showered on Uncle Max.

Dora insisted that Jocko was "Uncle Jakey," an old black man who sometimes

came to saw wood.

"It is Uncle Jakey, got all small. I know it is. He better go

in the kitchen wiz Woxy," -- and nothing would induce her to touch him

or regard him as a pet, playfellow, or friend.

She was much pleased with her own gift, her "pwitty wed butter," as

she called it, and stopped several times during breakfast to hug her uncle.

Roxy shared her pet's prejudice against the monkey, and went about holding

her skirts carefully from contact with him, and tossing her head in a way

she had when things did not please her. Her mistress secretly sympathized

with her, but was consoled by a private promise from Captain Max that he

would take away Jocko at the end of a week, if she really Wished it.

That afternoon Uncle Max took the elder children to the Museum, as he

had promised, allowing each of them to invite one of their particular friends

to go too. They were thus a party of five, and had a glorious time. The

only drawback was, that the captain bade them good by as soon as they reached

home, being obliged to take the night boat for New York.

"I shall be gone four or five days," he said, "and when I return I shall

expect to hear how many dozen oranges Annie has eaten, and how Sam's monkey

has behaved. Mind now, Sam, if you let him trouble your mother, I'll take

him away where you'll never see him again."

Sam grinned; he did not believe his merry uncle would ever keep the

threat. Like many other children, he did not know that one so lively and

good-natured could also, in case of need, be stern, just, and immovable.

At the end of a week Captain Max returned. This time he came late, and

all the children were asleep, the Doctor had been called out, and Mrs.

Sumner was alone. As soon as he was comfortably seated and his cigar lit,

he requested, and his sister gave him, The Sad Story of Sam's Monkey.

"O Max! such a week as this has been! I can laugh about it now with

you, but it has been no laughing matter for either the children, or Roxy,

or me, I assure you.

"You know, when you left, the creature was quite shy and still, and

would hardly move or eat. In the morning he still seemed so harmless and

depressed that I allowed Sam to leave him unchained when he went to school,

thinking he would feel more at home if he walked about a little. Accordingly

he did walk about, but very slowly and shyly. He seemed to take a fancy

to Roxy, and, though she hated him, followed her about closely while she

gave Dora her bath and afterwards washed some laces in the bath-room basin.

His aspect was so comically wise and attentive that we all laughed, and

felt more kindly towards him.

"By and by I went down stairs, leaving him asleep in a patch of sunlight

on the play-room floor, while Roxy and Dora were sitting as usual in the

nursery close by. I had hardly been down half an hour when piercing screams

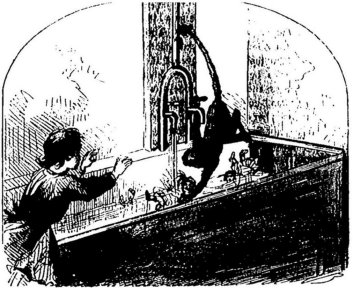

from Dora made me run up again. O such a scene! The perfidious monkey,

in imitation of Roxy's performances, had collected all the dolls from the

baby-house, thrown them into the bath-tub, and turned on the water, besides

putting to soak in the basin a pile of Dora's freshly-ironed white aprons,

which Roxy had left a moment on a chair. Poor Dora's grief, as she pulled

her drenched dollies out of their bath, was extreme. The china ones were

unhurt, except as to their dresses; but the large painted one was a melancholy

spectacle: the black of her hair and the red of her checks had run all

over her face, and ruined her white frock. I could think of nothing but

a savage in his war-paint; -- while the favorite wax lady, with real hair,

was painfully like a drowned kitten. Roxy's wrath was loud and long. The

monkey fled before it, and did not reappear until dinner-time.

"I'm sorry to say that Sam only laughed till he cried when he heard

of the ruin Jocko had wrought. But before night he realized that mischief

was not always so amusing. I allowed him to take the monkey out for a walk,

on condition he did not loose him or allow him out of his sight for a moment.

For a while all went well. Jocko made plenty of sport, pelting the boys

with acorns, riding on Ponto, etc.; but at last they grew tired of him,

chained him to the fence, and amused themselves by skipping stones on the

surface of the pond. Presently Mr. Monkey began to imitate them; and, though

his stones did not skip, he threw them so fast and made such ludicrous

imitations of the positions and gestures of the boys, that they screamed

with laughter and encouraged his play.

"Suddenly some one cried, 'He gets his stones out of your pocket, Sam!

O, my eyes! they're your marbles!' Too true! Sam had carelessly flung his

overcoat on the fence, and Jocko, smelling the gingerbread in the pockets,

had explored them all, discovered the marbles, and made rapid use of them.

Alas! the beautiful Chinese ones, the gorgeous glass ones, the agates,

the alleys, and the commoneys, were all deep in the middle of the pond.

Poor Sam! he gave way, forgot his manliness, and cried as bitterly as Dora

had over her drowned dollies. Jocko received a good whipping, and was chained

up for the night, with nothing but dry bread for his supper.

"Poor Sam was somewhat consoled the next morning; for kind Annie gave

him fifteen cents out of her own pocket-money to buy new marbles. On the

strength of this, he forgave Jocko, and fed him generously before he went

to school. I decided that the mischievous creature must remain tied; but

Sam made such eloquent representations of the harshness of solitary confinement

in the woodshed, that I commuted the sentence to a short rope under the

kitchen table.

"Going down there in the course of the morning, I found Biddy cutting

up fish for a chowder. She solemnly informed me that the monkey watched

her so closely that she was getting quite nervous. 'The wise-like look

of the baste is somethin' awful, marm; he sees ivery turn of me hand, and

it's all of a creep I am, with his stiddy watchin' and niver spakin', for

it's my belafe he could spake if he chose.'

"I laughed at her, gave my directions for dessert, and was leaving the

room, when she called my attention to the cellar door. The latch was out

of order in some way, so that to keep the door closed she was obliged to

bolt it. She dropped her knife as she turned to show me, but neglected

to pick it up until we had examined and discussed the broken latch. Promising

to have it mended, I went away, and she, stooping for the knife, noticed

with relief (as she told me afterwards), that Jocko had curled himself

up, and gone to sleep. Alas, poor Biddy! she little knew that, while she

was so volubly explaining the state of the door, the wily creature had

not only noticed that, but had used the knife to cut his rope, and was

only waiting for a good opportunity to make use of his liberty. His time

soon came. Biddy went down cellar, and her apparently sleeping enemy instantly

started up, closed and bolted the door upon her, and, with joyful chattering,

found himself master of the kitchen.

"His first exploit was a thorough foraging of the pantry. Here he ate

out the middle of two pies, consumed several cup-custards, emptied the

sugar-bowl upon the floor, the better to select the big lumps, and threw

the saltcellar through the window, because he did not relish its contents.

He next directed his inventive mind to the cooking, quite regardless of

the scolding of his prisoner, who was now wildly beating on the cellar

door. Having previously watched her putting the various ingredients into

the chowder, he now decided to add a few of his own selection. With this

in view, he pulled open the table drawer, and, finding there a pleasing

variety of objects, he proceeded by the aid of a chair and a towel to reach

and remove the cover of the kettle without burning his wicked paws, and

with wonderful swiftness he then added the whole contents of the drawer

to poor Biddy's savory stew.

"What his next achievement would have been we can never know, for at

this moment Roxy was heard coming down stairs to re-iron the white dresses

so rudely treated the day before. Jocko dropped on the cover, towel and

all, and ran to hide himself behind the flour-barrel in the pantry, and

Roxy coming in saw nothing amiss; but poor Biddy's cries were distinctly

audible, and in great amazement she hastened to open the door, and was

instantly overwhelmed with bitter reproaches from the furious prisoner,

who of course regarded nurse as the sole author of the joke. It was only

after the exchange of a great many loud words, and the copious shedding

of tears on cook's part, that they came to an understanding, and finally,

-- missing Jocko, -- to the right conclusion.

"Of course he was nowhere to be found, and peace was at last restored,

but not to continue long; for Biddy, going to the closet, discovered the

dreadful signs of invasion there, and set up a yell worthy of a wake. Roxy

at the same moment, stooping over the range for a flat-iron, perceived

an unaccountable odor, lifted the cover of the chowder-kettle, and immediately

sat flat down upon the floor and gave way to screams of dismay and laughter.

The noise of this duet reached even to the nursery, and Dora and I hurried

down, expecting to find the house on fire at least. O Max! if you could

only have been here! I have not laughed so since we were children, and

that bottle of beer burst, and blew off grandfather's wig. Roxy still sat

on the floor, lame and weak with hysterical laughing and crying, but not

quite able to subdue either; Biddy, with her apron over her head, alternately

bewailed 'the poor dear docthor's dinner spiled, and he niver mistrustin','

and threatened Jocko with every form of violent death.

"The state of the pantry was nothing compared to that chowder. There,

all boiling and steaming together, were slices of pork and rusty hair-pins,

flakes of fish and a ball of lamp-wicking, rounds of potato, a half-knitted

stocking, bits of onion, spools of cotton, and a big lump of beeswax, a

half-eaten apple, a pocket-comb, and a fancy fan, the 'Key of Heaven' reduced

to the consistency of the hard crackers, a lump of flag-root, and two or

three neck-ribbons floating on top. Such a time as we had fishing all these

out! But you can imagine the rest, -- how I scolded the girls into self-command,

and set them to preparing a new dinner, -- how the Doctor, not having his

regular Friday's chowder, forgot what day it was, and missed an important

appointment, -- and how Jocko crept out at nightfall, and received a suitable

compensation for his tricks.

"All day Saturday he languished in chains, and, though the children

invited their friends to see him, I would not allow him to be loosed. Sunday,

Annie was kept in by a bad cold, and I left him in her care without anxiety,

while I took Sam and Dora to church.

"Annie first established herself in her father's office with a book,

having chained Jocko to a chair and put the biggest volume of 'Anatomical

Plates' into it to keep it steady. Getting tired after a while, she went

into the parlor, leaving her charge safely anchored, and apparently asleep.

Unluckily for her, the Doctor came in for a bottle, and, seeing his beloved

book in a chair, carefully replaced it on the shelf and went out again,

unconscious of the monkey who was thus left comparatively at liberty. Annie,

trying to puzzle out 'Old Hundred' on the piano, had forgotten all about

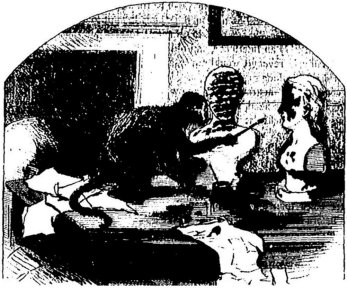

him, or rather she supposed him still asleep. But he was softly and gradually

dragging his chair to the table, and at last he brought it close, and his

chain allowed him to climb up and examine the Doctor's properties at his

leisure. The day before he had seen the children trying with paints and

brushes to restore form and beauty to Dora's drowned dollies, and some

remembrance of it must have been in his mind now, when he seized the mucilage

brush and bottle, and tried to embellish the great plaster busts of Aesculapius

and Hippocrates, between which he found himself.

"The results not being lively enough to please his tropical taste, he

next dipped his brush in the ink, and then indeed he saw the fruit of his

labors. When I returned from church, poor Aesculapius was metamorphosed

into an Othello, and Hippocrates was in a zebra-like condition of stripes,

while the artist himself wore an expression of absorbed delight. My cry

of dismay startled him from his rapture, and, with miserable whimperings,

he tried to hide himself in the paper-basket.

"As he was far too inky to be touched, I carried him away in It, and

had him once more chained up in solitude in the shed. Poor Annie had a

hearty cry over the results of her unusual carelessness, and her father

gave peremptory orders that the monkey should not be unchained or brought

in again during your absence.

"All trouble might have ended here, had Sam been obedient; but I'm sorry

to say the spirit of mischief is often stronger than anything else in that

boy. I should feel more troubled about it than I do, Max," she added roguishly,

"if I had n't seen such cases before, and known them turn out tolerably

well. Monday I had a peaceful day. Tuesday morning also passed without

annoyance. After dinner, however, the Doctor took the girls and me to ride,

giving Sam leave to spend the afternoon at Teddy Ray's. Unfortunately Teddy

was not home, so Sam came back, and, finding time hang heavily on his hands,

he yielded to temptation, and decided to unchain the monkey just for half

an hour, and have a good frolic with him for the last time. Roxy being

out, and Biddy in her own room, there was no one to check him, and, as

he fondly thought, no one need ever know of his misbehavior. So, going

into the shed, and carefully closing all the doors, he released Jocko,

who celebrated his liberty with many joyous leaps and droll antics. For

a while, all went merrily. Sam taught his new mate to play ball, and found

him a ready pupil. He says they threw it back and forth over a hundred

times without failing, and only stopped then because he laughed so at Jocko's

eagerness and spiteful throws. In this way time passed unnoticed. Teddy

Ray, meanwhile, having come home and heard of Sam's visit, came with boy-like

promptness to return it. Sam gleefully admitted him, made him promise secrecy,

and then proudly displayed the new accomplishment of his pet. Ted was delighted,

and would not hear of having such a playmate chained. "When we hear the

carriage coming will be time enough; let's have all the fun we can, Sam,"

And Sam yielded, as he is too apt to do, to the counsels of his older,

bolder ally. So the three began to play; but Jocko evidently considered

Teddy an interloper, and obstinately refused to throw the ball to him.

Teddy, in revenge, would not toss it to Jocko, who now chattered and squealed

with jealous rage. This, of course, was 'gay fun' to the boys, and they

continued to aggravate him; now withholding the ball entirely, now tossing

it over his head, and again pretending to throw it, and laughing and jeering

when he held out his paws for nothing.

"At last he was wrought up to a state of fury, and, snatching a broken

tumbler which had been set over one of Biddy's plants in the window, threw

it with true aim at his rival. Poor Ted's check was dreadfully cut, and

the blood streamed at once. Sam's temper was up in a moment. Brave as a

lion he sprung on the enemy; but Jocko was angry too, and gave his young

master more than one vigorous scratch, and pulled out two pawfuls of his

curls before he was conquered and chained.

"On this cheerful scene, the Doctor and I entered, followed by Annie

and Dora. Poor Teddy, faint and dizzy, sat on the wash-bench, leaning his

head against the wall, while his pale face and gayly braided jacket were

striped and smeared with blood. Sam stood over him, sobbing with fright

and remorse, trying to wipe away the stains with his little dingy handkerchief,

which he had soaked in water. Why is it that boys' handkerchiefs always

look so, I wonder?"

"Because they carry worms and pebbles and gingerbread and pitch and

liquorice paste in their pockets," suggested Uncle Max.

"Perhaps it is. But I must finish about poor Sam. His mingled relief

and shame, when he saw us, were very touching. 'O papa,' he cried, 'I am

so glad you've come! O, I have been very bad, and you may punish me hard,

only see to Teddy first, pray do! I will tell you all about it, only do

stop the blood. Poor Ted! it was all my fault, mamma, and you may send

away Jocko as soon as you please. O, will it make a dreadful scar, and

will Mrs. Ray hate me? I'm so sorry, Ted. I wish it was I that was cut

so. Don't mind my face, it's only scratched, but fix poor Teddy's'

"His distress when he heard that the wound must be sewed up was far

greater than Teddy's own, and I had much more of a scene putting him to

bed, bathing his swollen face, hearing his full confession, and soothing

him to sleep, than the Doctor had with Ted in the surgery. All this time

Annie had her share of consoling to do; for poor Dora, who had never seen

more than a drop of blood at a time before, thought that both the boys

were 'deaded,' and was crying with all her might. I assure you, I have

had to feed the monkey myself ever since, for no one else will go near

him. And you will take him away early, to-morrow, Max, won't you? and not

reproach Sam; for the sight of the results of his disobedience has been

a severe punishment to him already."

"I will do just as you say, Molly," said Uncle Max, very gravely. "I

am beginning to feel that I was wrong to bring such a playfellow to your

quiet home; but, as I told you before, I only borrowed him of one of the

sailors, who will call for him to-morrow. I am sorry I ever did so thoughtless

a thing. I hope Annie's oranges have not been unfortunate too?"

" No, indeed," said Mrs. Sumner, with a happy smile; "that story will

be quite a different one."