Volume 1812b

Georges Dodds'

The Ape-Man: his Kith and Kin

A collection of texts which prepared the advent of Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Presents

http://www.erbzine.com/mag18/berthet3.htm

| Chapter XI. | The Fontaine-des- Laves. |

| Chapter XII. | Bereavement. |

| Chapter XIII. | The Pursuit. |

| Chapter XIV. | Found and Lost. |

| Chapter XV. | The Forest. |

| Chapter XVI. | The Return. |

| CONTINUED IN PART IV |

The thought that they were going to torment the captive ape by depriving him of food and sleep, or even kill him perhaps, worked in young Palmer's brain. After the tales of the negroes and other people about him, Edward no longer looked upon the ape as a beast, but as a kind of man deprived of speech; or, at least, as a being half-way between a man and a brute. So his childish honour led him to think that he ought to pay his debt of gratitude to his deliverer. But how was it to be done? Darius had certainly said that a bit of rope would suffice to work the prisoner's deliverance, but where should he find a rope? And then how should he get out of the house? The first person that met him alone in the country would think it right to take him home, where he would get a sharp scolding for his prank.

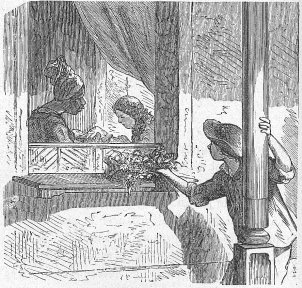

Busy with these reflections, which, as one would naturally expect in so young a child, were rather vague, he made up his bouquet, placed it on the window-sill, and slipped into the court. He had no fixed plan yet; he would have obeyed the first call from the house. But his father was writing in the drawing- room, his mother and aunt were up-stairs; Anna was listening in the little room to an African story that the negress was telling; nobody seemed to be thinking about him, and he was left to follow the suggestions of his adventurous disposition.

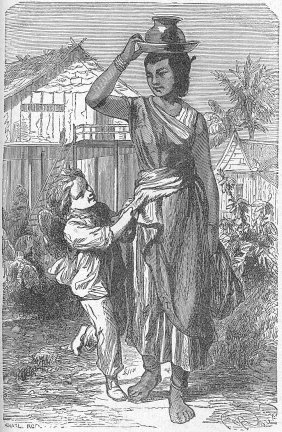

This little theft committed, he began to wander about the court. It was quite deserted. A Sumatran hut, built on piles, with a wooden ladder up to the door, seemed to be the only one where anybody was at home. A monotonous song, not altogether wanting in melody, issued from it; it was Elephant-Slayer's daughter humming to herself. After a time Légère came down the ladder. Though she was not dressed in all her holiday ornaments, yet she still preserved the proud and rather hard beauty that characterizes the Malay women. Draped in her sarong, she was carrying an earthenware pot on her shoulder, and was supporting it with her bare arm, like a sculptured statue; in her other hand she held something wrapped up in a palm-leaf.

She went on singing, and chewing her betel, and she was going away without paying any attention to Edward; but the child went up to her coaxingly:

"Légère," he said in the patois of the colony, "where are you going?"

"To Fontaine-des-Laves," replied Légère, without looking at him.

"And why are you going to Fontaine-des- Laves?"

"To take my father his food, and to tell him about the wounded cock."

"Is the cock getting well?"

"Yes."

And she was just going on when Edward caught hold of her by the folds of her sarong.

"What do you want to do there?"

"I want to see the orang that they have got prisoner there."

The Malay girl was very much flattered by this request; for in spite of her national pride she had often envied the familiarity that existed between her master's child and the other women belonging to the house. However, she answered dryly:

"You are forbidden to go out with me. My master and mistress will scold me, and my father will beat me. Go home!"

Edward was offended at this not very gentle refusal; but his desire to go to La Fontaine only increased with contradiction, and he answered, coaxingly:

"You know why they won't let me go out with you? It is because they say Malays eat human flesh. Aunt Surrey told me a story of a horrid woman who ate children, and who had pointed teeth like yours. But I am not afraid of being eaten --- I am a man; and then the horrid woman was ugly, and you are very pretty."

This artless reply, which seemed, however, so cleverly put in, induced the young girl to consent.

Did Légère want to play a trick on those who accused her of cannibalism, or did she only yield to the irresistible power of flattery? Perhaps both motives influenced her, and she answered: "Come, then."

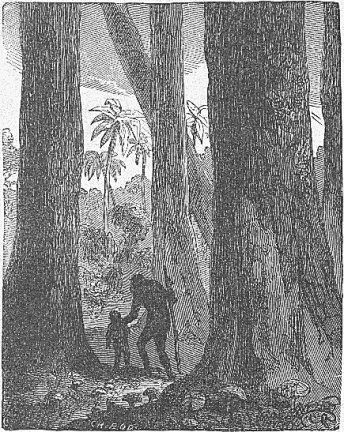

She set off at a good pace, and, though she was bare- footed, Edward had some difficulty in keeping up with her.

The child was afraid at first of being seen from the house, and while they were in the avenue he kept looking behind him anxiously; but they soon left the beaten path, that they might take the shortest way to Fontaine-des-Laves. Then not being afraid any longer of being met and taken home, Edward was soon at ease again, and recovered his natural assurance.

Légère, as she crossed the fields of rice and pepper with her pot on her shoulder, did not seem to trouble herself about her little companion, and went on humming.

"What are you carrying there, Légère?" asked Edward carelessly.

"Not human flesh, child. It is a piece of goat, and some rice, and bread-fruit cooked in the ashes."

Edward, abashed by this rough reply, did not venture to say any more; and Légère continued her song, taking a bit of betel from her box every now and then.

At the end of a quarter of an hour they reached Fontaine-des-Laves. Elephant-Slayer, Darius, and the other hunters, were guarding the rocks at the source of the stream. Certain that the orang could not climb the walls of the cavern, they contented themselves with guarding the passage by which he had entered, to hinder him, if need were, from throwing down the pieces of rock that closed up his prison. However, they did not really believe such a thing possible, even for their vigorous adversary, for they were fulfilling their task very negligently, and, lying on the grass, they were playing at dice and other games of chance popular in the colony.

The sight of Edward caused them some astonishment and uneasiness. Although there seemed no cause for alarm, they could not see the beloved son of the richest planter in the neighbourhood exposed to one of the accidents so common in that terrible country, without apprehension. Darius wanted to take him home again directly, and tried to take hold of him; but Edward resisted, scratched, and bit so violently, that the poor negro, not daring to employ force, let him go, determining to watch all his movements and prevent him from doing anything he should not. On his part, Elephant-Slayer seemed much irritated with his daughter, who had acted as guide to the child, and he scolded her well in Malay.

She did not put herself out at all.

"He would come," she said coldly, placing her provisions on the ground.

Edward hastened to have his say.

"Yes, I wanted to come," he answered, in a resolute tone; "and who could hinder me? I am master, surely; and I am not afraid." This decision in so young a child could not fail to please Elephant-Slayer.

"And why did you want to come?" he asked Edward more gently.

"To see the wild man of the woods." The Malay pointed with his finger to the blocks of basalt, at the top of which were some trees and brushwood; and anyone looking down from there could see into the pit where the orang was confined.

It would be mere play for Edward, accustomed to all kinds of bodily exercise, to climb the rock; but, before trying the ascent, he seated himself on a stone at Slayer's side, and said to him in an insinuating tone: "Have you not given the wild man of the woods anything to eat since the morning?"

"Nothing."

"Won't you throw him something this evening?"

"No."

"And to-morrow?"

"No. The orang is fierce because he is strong; hunger will subdue him. When he has fasted for three days, he will let himself be taken and bound. Then I shall give him to Van Stetten, who will pay me twenty gold pagodas, --- and I shan't let anyone else have any of them!" he added, as if speaking to himself, and putting his hand on the handle of his kris.

"But if," asked the little boy, "hunger does not make him more gentle, what will you do?"

"I shall climb the rock, and shoot him with poisoned arrows. They do better than bullets; but they forbid us to use them."

Edward, on learning the fate of his protégé, felt inclined to cry, but he restrained himself.

"O Slayer, you won't be so wicked as to make the poor orang suffer like this? Only think, --he killed the tiger that was going to eat me up."

"Yes; but he killed Smoker, a Malay, and a Batta, and he broke the gun that was my father's. I will be revenged!"

Now Edward burst out crying.

"Slayer," he said, clasping his hands. "let the wild man go, I beg you. When I am a big man, I will give you a great many golden pagodas, and fine guns, and fighting-cocks. But I shall be so sorry if you torment or kill the poor orang that saved my life."

Edward had gone the wrong way to work; tears and supplications produced no effect on the fierce hunter; ElephantSlayer shrugged his shoulders.

"You are a child," he said contemptuously; "and a Batta warrior should not have listened to you so long."

He turned away his head, and began to eat the provisions that his daughter had brought. Then, having eaten as much as he required, he played away the remains of his meal with the other hunters, who had not left off their games of dice and huckle-bones.

Thus Edward was left to his own devices. Darius, who ought to have watched him, was chatting with Légère. No one stirred when the child, after hesitating for some minutes, began to climb the rocks. Scrambling up on his hands and feet, he soon reached the top. There, he found himself on the edge of the chasm, and looked down fearlessly. In spite of the growing darkness a little basin was visible at the bottom of the fissure, from which the clear, limpid water was flowing gently out in the channel which served to carry it away. On a narrow ledge of ground which surrounded the basin was the orang-outang. The walls, being perpendicular, rendered every attempt to escape from this well- like place useless.

The orang had, however, made incredible efforts to climb up, as the state of his nails and his hands, bleeding from the roughness of the rock, testified; but now, leaning against the rock, his long arms hanging down by his side, his eyes sad and gloomy, he stood motionless, and seemed to have lost all strength and courage. Then he heard a slight noise overhead, he started and looked up. No doubt he recognised Edward, for his eye, all at once, assumed an expression so sad, so gentle, and at the same time so supplicating, that it was impossible not to be touched by it.

Up to this time, we repeat, the child had not clearly made up his mind what he meant to do. He had come there as much out of a spirit of opposition and curiosity as with the intention of helping his friend in distress. But seeing the orang so weak, so dejected, almost dying, he felt an ardent desire to help him without delay and by any means.

"Oh, dear! perhaps he is hungry," he thought.

He drew a beautiful ripe fig from his pocket, which he had reserved for his own particular use, and threw it generously to the orang; but the latter seemed too much afflicted by his present situation to dream of eating. The fig fell close to him, and he did not exert his usual skill in catching it; he still continued to gaze at the child with eyes full of intelligence, grief, and entreaty, as if to beg more effectual assistance.

Then Edward remembered the rope he had in his pocket; but, before putting it to any use, he resolved to see what the hunters intrusted with the blockade of the Fontaine were doing. Elephant-Slayer, with his usual desperation, was playing at dice with his comrades, while Darius and Légère were still chatting. No one was noticing little Palmer; nobody seemed to be thinking of him.

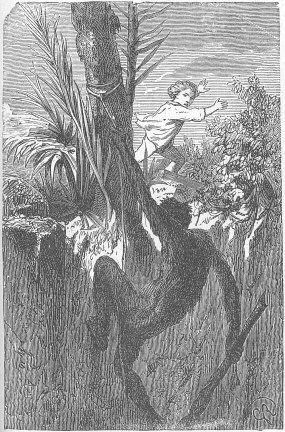

Having made sure of this point, he began to undo the rope he had brought. Although it was pretty thick, yet it seemed much too weak to bear the weight of such a wild, heavy creature. Besides, supposing it did not break, how could the orang, exhausted by fatigue and hunger, raise himself up to the edge of the chasm? And the least noise, the least failure, would attract the attention of the hunters, and render the enterprise altogether impossible. In spite of these apparently insurmountable difficulties, Edward, to quiet his conscience, fastened one end of the cord firmly to the trunk of a palm-tree that had struck its roots into the clefts of the rock; and then he threw the other end into the cavern. He hardly expected any result from such a simple contrivance, but still he leaned over to see what would happen.

What happened took place so rapidly that he was struck dumb with astonishment. The orang had watched with marked attention, but without stirring, all Edward's movements. When he saw the rope drop, weak as he was, he raised himself at once; with one prodigious leap, he sprang across the basin of the spring, seized the rope, and climbed to the top of the rock with inconceivable agility. In the twinkling of an eye he was at his deliverer's side, and, brandishing his club, which he had not thrown away, he uttered a hoarse, commanding shout, as if to proclaim his triumph!

The hunters took alarm immediately, and they had little trouble in guessing part of the truth. Their play and talk were put a stop to, and each one seized his bow or his gun, and began to climb the rock; but, notwithstanding their haste, they came too late.

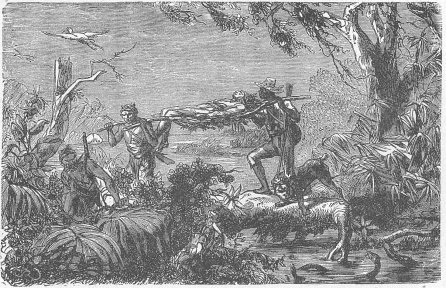

The orang went up to Edward, picked him up carefully, and was turning him round with an air of surprise when the hunters arrived. Threatened by so many enemies, he settled what to do at once. He threw away his club, pressed Edward to his shaggy breast, and, seizing with his other hand the trunk of the nearest tree, climbed to the top, in spite of his burden, with the rapidity of thought.

The hunters, seeing the only child of the rich planter carried up into the air in this way, trembled lest he should be dropped from that frightful height, and did not dare to use their weapons, for fear of hurting him. As for the child, made giddy at first by the rapid motion, he was not long in coming to himself, and began to cry for help in all the different languages he knew. Then it was that Elephant-Slayer and the rest, in the hope of frightening the orang into leaving his prey, fired a few random shots, and uttered the shouts that were heard far off in the country.

This proceeding did not have the result that they expected. The orang did not intend to give up his prisoner so easily; hugging afresh the poor child, who was still uttering cries and supplications, he sprang lightly to the next tree, and from that to another, till it was soon evident that he would succeed in gaining the forest, where he would be sheltered from all pursuit.

Although these rough men were not easily affected, they did seem touched by the terrible situation of Edward, and left nothing undone to cut off his captor's retreat. They descended the rock, and ran hither and thither, shouting incessantly, and loading and firing their guns. Unfortunately the trees, though sometimes rather scattered, reached without interruption to the forest, and the orang, by springing from one to another, was able to brave their attacks.

Another circumstance now increased the difficulties of the pursuit. The violent wind that preceded the storm had already risen in the valley, as we have said, and was raising clouds of dust and dried leaves, while the trees, beating against one another, made a frightful tumult. In the midst of this commotion, the hunters, blinded and deafened, could no longer follow the movements of the orang or hear the lamentations of his victim.

Besides, Edward's voice grew weaker and weaker, either because he was so high up, or because he was out of breath with the prodigious leaps that the orang made with so much ease and agility.

The last time that they were both seen, they were on the old bombax, at the foot of which the scene with the tiger had taken place a few days before. For a moment there was an interval of calm, and from a distance they could distinguish the great form of the orang-outang and the white clothes of the little boy.

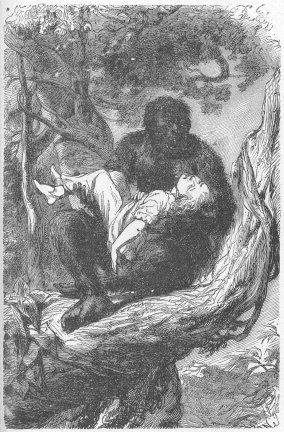

It was strange; but one would have said that the orang was aware of the suffering and fatigue of the frail creature he had stolen. He took pains to save him from too violent shocks, and very cleverly pushed aside the branches that might have hurt him.

For a minute even, seeing that he was some way in advance of his enemies, he stopped for an instant to let him take breath, and rocked him gently in his long arms like a nurse. In spite of these precautions, Edward seemed nothing but a dead weight; his frail body was bruised as if he had had a violent blow, or as if he were already dead.

The hunters lost all heart; the undaunted Elephant- Slayer alone went on, saying:

"The orang has done me an injury, --- a Batta warrior must revenge himself !"

He was very rash to venture into these solitudes so late in the evening, where he would be exposed to all kinds of dangers. Some of Slayer's comrades, however, followed him into that part of the wood where the colonists had made some clearings; but at the border of the forest itself they dispersed under pretext of continuing the search in different directions. In truth, convinced of the uselessness of trying to deprive the orang of his prey, they now only thought of getting shelter from the storm as quickly as possible.

"Where is the wild man of the woods? Where are they all? What has happened?"

Légère looked at him in an absent way, took a lump of betel from her box, and answered at last without any emotion:

"They have all gone after the orang."

"Tell me," continued the planter, trembling with impatience and fear, "what has happened here just now?"

"The wild man of the woods has run away, and carried off the child."

"What child?"

"Edward, --- master's little boy. Edward threw a rope to the orang, and the orang ran away and took Edward with him."

We must pardon Légère for her heartlessness; she was a Malay, and she was not a mother; who could have made her understand that such news, told in such a way, might have been a death-blow to poor Palmer?

On learning the terrible truth, Palmer felt as if a dagger had entered his heart; but he hardened himself against the feeling, and asked, in a voice scarcely intelligible, which way the orang had gone. Légère pointed to the old bombax, and he rushed off in that direction, exclaiming:

"Edward, my darling Edward! what will Elizabeth say?"

The girl watched him as he went, struggling with the violent gusts of wind; then she lifted the pot on her shoulder again and returned home, without seeming to have any idea of the harm she had done.

In a few minutes Palmer reached the bombax; but he looked in vain for his child's captor, or the hunters that had pursued him. It was growing dark rapidly, the fleeting brightness of a few distant flashes of lightning scarcely relieved the increasing darkness. The planter tried to shout, but the roaring of the storm drowned his voice.

Sometimes, in the midst of the uproar, he thought he distinguished sounds of lamentation, and human voices answering to his call; but he soon found that he had been deceived by the kind of dismal groaning that the wind makes as it dies away in the forest.

Nevertheless Palmer was not to be daunted. Unarmed, bare-headed, for he had lost his hat as he ran desperately along, his clothes in rags, his hands and face bleeding with the thorny shrubs through which he dashed, he went on his way at all risks, calling his son with a voice that was hardly audible.

He asked him quickly if he had any news of his son.

"I have seen nothing," answered Slayer angrily.

"Well, we must go on looking," replied Palmer energetically. "Slayer, you are a brave, experienced hunter; you are acquainted with life in the woods; help me to find my darling Edward."

"To-morrow."

"Why to-morrow? why not this very minute? Perhaps by to-morrow the wretch will have throttled my boy, or else the child will be dead with fatigue and terror."

"The orang will not kill Edward," said the Malay coolly; the men who do not talk are fond of children, and take great care of them. Master, don't go into the forest now."

"Do you think, then," answered Palmer impetuously, "that I am afraid of tigers and other wild beasts? I shall take the child back to his mother, or perish in the attempt!"

"Slayer is not afraid either; but we can see nothing, we can hear nothing, during the night and during the storm."

"It is beginning to lighten, and in a little time the lightnings will make the wood as light as in the day-time; perhaps we shall be able to see my son."

"Master! Master!" answered the Malay impatiently, "don't disturb the orang; he is hiding no doubt somewhere near; if you do disturb him he will certainly run very far away with Edward, and we shall never find them again."

There was some justice in these remarks; but the fatherly affection and blind despair of the planter hindered him from seeing it.

"I won't leave my child like that," said he. "I will never leave these woods till I have found him, even if I have to hunt for him all night."

And he turned to enter the wildest part of the forest, from which just then a frightful noise issued --- a sound as if all the wild beasts in the world had met there to howl at once. The Malay, offended at this obstinacy, did not try any more to detain him, and was going to return to the settlement, when someone was heard calling in the distance. At the same time torches were seen among the trees, and several persons appeared, running quickly. As Richard turned round, his wife, pale and tottering, threw herself into his arms, crying in a broken voice:

"Richard! dear Richard! where is our child?" Mrs. Surrey had come with Elizabeth as well as little Anna; all three in the loose dresses they wore in the house, and without anything on their heads. In fact, Légère had not been more careful in telling her mistress how Edward had been carried off than she had been in telling her master. On learning the terrible news, the gentle mother had fainted; but she soon recovered, and, with the strength of fever and despair, set off towards Fontaine-des-Laves. Anna and the quiet Mrs. Surrey, herself hardly less overcome, had followed her, mingling their cries and tears with hers. Everybody belonging to the house, even the most selfish and impassive Chinamen, had accompanied the unhappy family. A few of the villagers had joined them on the way, and they arrived just when Palmer, mad with grief, was trying to penetrate the inextricable thickets of the primeval forest. Elizabeth's question seemed to excite her husband to the last degree.

"I will bring him back to you, Elizabeth," he cried, "I promise you. Leave me alone --- go home! I must recover the son that God has given me for my comfort and joy!"

"Ah! is he not my child as well as yours?" answered the mother impetuously. "Richard, I will not leave you !"

"And me too!" cried little Anna, sobbing.

"Oh, do let me go with you to look for Cousin Edward!"

By the light of the resinous wood torches that the negroes carried, Palmer looked at his wife and the child who wanted to be his companions in his perilous expedition. Pale, feeble, and out of breath, they could hardly stand; and it was a wonder how they had managed to come so far. While he was urging them to return home, Mrs. Stirrey, who was much calmer than the others, though not less grieved about the child, had been questioning Elephant-Slayer and the other hunters of the country on the expediency of making an immediate search under such unfavourable circumstances. She hastened to interfere with the authority that deep conviction and sincere affection inspire.

"Brother and sister," she said firmly, "your grief bewilders you; it is impossible to attempt to do anything this evening for the poor child. Richard, I beg you to wait till to-morrow morning, if you want your search to be of any use. At this time of night, in such perfect darkness, what can be the use of going into that thick wood, full of fallen trees, and swamps, and wild beasts? Besides, the storm is only just beginning, and will certainly get worse and worse, till it will be impossible to brave it. And then, too, if you want to make sure of success, you must go wisely and thoughtfully to work. Wait till to- morrow."

"But to-morrow will be too late!" cried Elizabeth in her turn.

"They tell me that they are sure we may trust the orang's wonderful instinct to preserve our Edward from all harm, and that there will be more chance of finding him to-morrow, if we do not give the alarm to his captor this evening. Come, Richard and Elizabeth, I beg you, in the name of all that is most sacred, for the sake of the poor child himself, go home again."

"Well," said Palmer, "take Elizabeth and this child home with you; they can be of no use; but as for me, I have made up my mind. I shall go and look for my boy!"

"Richard, I will go too!" cried Elizabeth, leaning against a tree to keep herself from falling.

"And I, too!" repeated Anna.

"Nobody shall enter the forest at this time of night," said a man's voice, suddenly from among the spectators; it would be extremely imprudent and foolish, and I will not allow it!"

It was Major Grudmann, who had just arrived with Dr. Van Stetten; both having heard of the misfortune that had befallen the Palmers, the storm did not prevent them from coming to express their sympathy and offer their help.

Palmer, in spite of the gravity of his situation, reddened with anger at receiving such a positive order.

"In virtue of what right, Major Grudmann," he asked, "do you presume to impose your commands on me?"

"In virtue of the right of humanity, Mr. Palmer --- the right that any man has, whoever he may be, of hindering an absurd and useless sacrifice; or, if you must have it, the right that my title of Governor and first magistrate of the colony gives. To-morrow, if you insist, you shall be at liberty to venture into those solitudes, where perhaps no human creature has penetrated before; but this evening the danger is too evident, too certain, for me to allow you to risk your life for nothing, and I hope you wi1l consent to listen to reason."

The Governor, who thought a great deal about his authority, was a man who would have it respected at any cost. However, Richard not seeming willing to give way, Van Stetten hastened to interfere.

"Come, Palmer," he said, "yield to evidence. Other duties, other feelings, have a claim on you. Look at your wife."

In truth, now that the first excitement was over, Elizabeth's strength began to fail her rapidly; and at last she sank into the arms of her sister-in-law and Maria, murmuring:

"There's no hope! there's no hope! My child is lost!"

Richard ran to her, but she had fainted; and perhaps it was hardly to be regretted that she had lost all knowledge of what was happening.

At this moment the wind, which had only blown in gusts till now, burst forth suddenly with a violence and persistence quite alarming. Now it was plain that the intervals of calm were at an end, and that the typhoon of the Indian seas was about to display its wild and terrible power. The torches of the negroes, in spite of the tenacity of the flame, were suddenly blown out. The tops of the highest palm-trees were bent to the ground, and a great number were snapped by the tempest. In the forest there was not a green thing, from the gigantic bombax to the weakest reed, that did not seem to be uttering a moan --- a cry of distress.

At the same time one would have thought that the whole sky was coming down upon the earth; the rain fell in torrents, and the clouds of leaves and dust which darkened the air were laid in a moment. Above this tremendous, universal tumult, the thunder raised its mighty voice; not that grave, majestic thunder, which roars at intervals in our temperate climates, but tropical thunder, continuous, deafening; which bursts like the explosion of a thousand cannon at once, flashing flame like a volcano, and frequently accompanied, in Sumatra, with earthquakes.

In face of these terrible convulsions of nature, man feels so small, so insignificant, that his fiercest passions are silenced at once. Such a change took place in Richard; the planter saw at last the danger of persisting, the absurdity of his hopes.

"God forbids it!" he said sorrowfully. "Poor child, forgive me for waiting a few hours before I come to your help, and for thinking of your mother first."

He raised Elizabeth, who was still fainting, in his arms.

"Sister, and you, Anna," he said firmly, "we must go home quickly. Doctor, don't leave us, I pray you, for we shall need you."

"I fear so," replied Van Stetten, sighing; "your good, kind wife had no need of this fresh shock. But go on, I will follow you."

"That's right," said Major Grudmann; "my good neighbour has turned sensible at last. Well, I must crave your hospitality to-night, for your house is the nearest, and the storm seems as if it would be no joke."

They set off at once. Nature seemed mad or intoxicated around them: every moment, great branches, or even whole trees, threatened to crush them in their fall; while at every step they were almost blown down, and several of them were carried off their feet. The rain blinded them; happily, notwithstanding the want of torches, there was no risk of losing their way in the darkness; dazzling flashes of lightning, which succeeded one another without intermission, made it as light as day, and the lightning striking several points at once, kindled fires which the wind and rain soon extinguished. The colonists walked as much as possible close to one another, that they might be better able to resist the storm. The negress Maria helped her master to carry Elizabeth, whom even these torrents of water did not revive. Mrs. Surrey had taken her daughter Anna in her arms, still crying about Edward. The others followed, helping one another as best they could, and calling out now and then in a loud, sharp tone of voice, which was the only way of making themselves heard above the tumultuous noise of the elements.

But Palmer did not trouble himself about it just then; he was only thinking of the alarming state of his wife, whose fair hair, streaming with rain, blew about in the wind. When the bluish light of the flashes lit up Elizabeth's pale face, she looked like a corpse. Every now and then, too, Palmer turned his head towards the forest. Once he even stopped suddenly: in the midst of the roaring of the tempest he thought he could distinguish the clear voice of a child --- a voice that made his very heart-strings quiver. But he soon discovered his mistake, and went on.

At last they reached the house: that, too, had suffered. Several of the negroes' huts were thrown down; the wind was threatening to blow off the roofs of the other buildings; and the waters of the neighbouring cascade were beginning to overflow the garden. But Richard did not notice these ravages, any more than those in the plantations. He entered the lower room, whither most of the others followed him; an old negress, who took care of the house, bringing a light. Without laying down his precious burden, he said to. the Governor in a tone of cordiality:

"I ought to apologize to you, Major Grudmann. Show that you are not offended with me, by giving your orders here as if you were at home. Dr. Van Stetten, you must come to my poor wife directly she is in bed: meanwhile, all I have is at your service. Sister, take care of yourself and your little girl. But above all," he added, raising his voice and employing the language common to the different inhabitants of New Drontheim, "don't let my servants forget that I must be in the forest before daybreak to-morrow." At the same time he carried Elizabeth to her room, leaving his guests and the other inhabitants of the house to recover as best they could from the fatigues of the evening.

The storm lasted a great part of the night; it was not till near morning that, the rain, thunder and wind having subsided, Major Grudmann and his people could leave the house to go to their own dwellings.

However, the Governor, before leaving, very thoughtfully organized a little party that, under Palmer's direction, was to begin an active search as soon as it got light. It consisted, in the first place, of Elephant-Slayer, who had an ardent desire to avenge his private wrongs on the orang, Edward's captor, and of Boa, another Malay attached to the military force of New Drontheim, who was to act as guide or scout. Boa, who was so called on account of his skill in climbing trees and in creeping through the densest thickets, had penetrated, it was said, further than any other hunter in the colony into the vast forests of the neighbourhood, and his peculiar experience could not fail to be of great use. The negro Darius, a tolerable marksman, and, above all, strongly attached to Palmer, was also to accompany his master and carry his baggage. These were all; for a greater number of persons would have been worse than useless, considering the difficulties and dangers of such an expedition.

The Governor himself took the greatest pains to point out all the steps that should be taken to provide against all contingencies, recommending that the travellers should be well armed, and supplied with provisions for several days, in case they lost their way in those unknown solitudes. Grudmann spoke himself to Elephant-Slayer and Boa, who was also in the house, particularly to the latter, and threatened them with the most terrible punishment if they gave Mr. Palmer any cause to complain of them; while he also made them the most brilliant promises in case they succeeded in bringing back father and son safe and sound to the colony. It was not till he had made all these arrangements, of which Richard was not in a state to think just then, that he consented to go home.

As soon as the first rays of light began to tinge the sky, the two Malays and Darius were up and equipped for departure. Richard, who was seated in extreme dejection at the side of his wife's bed, his face hidden in his hands, was told that they were ready. He got up in silence and went out. Five minutes after he returned in the dress that he usually wore in hunting --- a hat of palm-leaves and trousers and jacket of leather, fastened tightly round the body, to prevent the thorns penetrating; he was armed with a long heavy gun, a pair of pistols, and a cutlass, intended more especially for cutting away creepers and other climbing plants. In spite of this warlike equipment, Palmer looked so pale, so sad, so crushed, that his very look inspired pity.

By the light of a candle in the room he went up to the sickbed. Since Elizabeth had recovered from her fainting fit, she had been constantly delirious, and had not spoken connectedly at all; but now, as her husband bent over her to kiss her, she opened her eyes, and said in an indescribably touching tone:

Weeping, the planter stammered out a few words, but Elizabeth did not understand him. The excitement of parting had only for a moment got the better of the illness that was preying upon her, and she became again delirious.

Palmer perceived it, and, after having given a last kiss to his poor wife, he made an effort to tear himself away from the sad spectacle. But then he felt himself gently detained by his sister and niece. Mrs. Surrey, always sensible, and understanding that any injunctions would be useless, wept in silence.

Little Anna, pale and trembling in her nightdress, said, clasping her hands:

"Oh, uncle! you will bring back Cousin Edward, won't you?"

Palmer turned away his face.

"Ask God, Anna," he said, in a hollow voice; "God alone can enable me to bring the poor child back!"

"Mind you come back, Richard," murmured Mrs. Surrey, sobbing.

"And come back quickly," added the doctor in his turn.

Richard freed himself from the embraces of his niece and sister.

"What do you mean, Van Stetten?" he asked, half distracted; "is Elizabeth in danger?"

"I hope not; but the shock has been severe, and delirium is not a good sign in this horrible climate. We shall want good news to act beneficially on her mind."

In spite of the doctor's reserve, Richard felt that his wife's very life depended on the result of his perilous enterprise; however, he was silent, gave a last kiss to his family, and went quickly out of the room.

Van Stetten followed him into the hall, where the two Malays and Darius were waiting for him; he appeared to have something to say to the planter, though he seemed rather shy of mentioning it. Richard begged him to leave his wife as little as possible during his absence.

"Trust to me," answered the doctor; "I will take up my abode here till your return. But, on your part, could you not make some observations on this animal which is so rare and so little known, the orang-outang? You can't imagine how valuable these scientific observations would be; and if you only had an opportunity of measuring its facial angle, or if you could make sure that the great toes of its feet are not opposable as some travellers maintain ---"

Palmer made a gesture of impatience; but he gave the doctor's hand a last squeeze, and left the house with the three men that were to accompany him.

The country was still enveloped in darkness, but a faint light began to be visible in the sky towards the east. They hastened to reach the forest before the rising of the sun should drive the orang deeper into its recesses. The thunder and rain had ceased, although the wind was still very high, and large clouds were moving rapidly along overhead. The hunters had to walk with the greatest caution over the ground, which was strewn with rubbish: in one place there were piles of rocks or trunks of trees brought down by the torrents; a little further on there were pools of muddy water, that compelled them to leave the direct road. The whole aspect of the land had been changed in a single night; entire plantations had disappeared, deep hollows had been made in cultivated fields; anyone most familiar with these spots could never have recognised them under the layer of mud and dust, leaves, branches, and rubbish of every kind with which they were now covered.

But Richard had other things to notice. His look was frequently directed to the forest itself, over which the first rays of light were just appearing, and sometimes his eye rested on the bold men whom he had chosen to share his toils and dangers, as if he was considering what degree of confidence he might place in them.

The negro and the two Malays were dressed in almost the same manner as Palmer was, with coats of thick leather, fastened tightly round the body; contrary to their usual custom, they wore boots, or rather sandals, to protect their feet from the thorns or the sharp points of the rocks. Besides their long guns, pistols, and krises, or curved cutlasses, they were loaded with provisions and such baggage as could not be dispensed with on such an excursion. Boa might have been about forty, an advanced age in that fatal climate, and his height was rather below the average. However, his iron muscles, which stood out beneath his olive-brown skin, showed that he was possessed of considerable vigour. The most perfect harmony seemed to exist between him and Elephant- Slayer, not that such men were likely to experience those feelings of humanity and pity that might have sustained them in their enterprise, but they counted on sharing the reward promised if they succeeded in their attempt, safe to fight when the time for dividing it came. Only the negro, Darius, faced the danger out of devotion to his master and the lost child. Unfortunately, Darius was the weakest, and the least experienced of the three, and perhaps he might himself require help from his bolder companions.

On the recommendation of the Governor, Boa had brought with him an ally, whose services under the circumstances were not to be despised. This was a large dog, with a shaggy coat, with a ferocious but at the same time intelligent face. This dog wore round his neck a collar ornamented with points, and he was held in with a thick leathern thong. Endowed with an excellent scent, he went along with his nose close to the ground, and when he discovered the track of the fallow deer that the storm had driven from their retreat during the night, he pulled at his leash and growled, and his master had some difficulty in making him leave the track. Such as it was, the little band seemed exactly suited to the exigencies of the situation, and, under the direction of Palmer, could scarcely fail of success in their object, if, however, this object were not beyond the reach of human effort.

It was, however, towards this tree, in which the orang had been last seen the evening before, that the hunters directed their way. As he approached it, Richard perceived that he was walking over the ruins of the krouboul, the wonderful flower that had attracted his son two days before to the fatal spot, and he uttered a melancholy sigh at the remembrance.

The Malays consulted together about the direction they should take; but it was not thought prudent to proceed further into the wood while it was still so dark. Happily, it was not necessary to wait long; the light soon broke forth and rendered the outline of surrounding objects clearly visible. The sun was hidden from view by the masses of dark clouds which still covered the sky; but it was now possible to see the difficulties and dangers of the road, and the singing of a few birds, heard above the moans of the rustling of the dying wind, told that nature was waking up again after the frightful convulsions of the night. Then Boa turned to Darius, and said to him, abruptly:

"The child's frock!" The negro took something of small size from his bag; and Richard recognised, with a mixture of emotion and surprise, one of his child's garments.

"What are you going to do with that?" he asked in a stifled voice.

"Massa go see," answered Darius.

And he gave the garment to Boa. The latter took it and made his dog smell it.

"I understand," cried Palmer; "that is a good idea! Oh, if the fine fellow could only find any trace of Edward!"

The two Malays beckoned to him to remain perfectly silent, and Boa said to the dog, "Now look."

The animal sniffed the different smells with which the air was loaded, and seemed to hesitate for some minutes; but he soon turned towards the forest, sniffed again in a very noisy fashion, and concluded by looking fixedly in the same direction, tugging at the leash and wagging his tail and ears.

"He has found the scent," pronounced Boa.

No words could express Palmer's pleasure; his heart beat violently, and he was on the point of speaking when Elephant- Slayer stopped him again.

"Don't speak," he said, in a low tone, "or the orang will run away with Edward directly. We must walk quietly; the man of the woods will hear the least sound, and perhaps he will try to defend the child; a single blow from his club might stretch one of us dead who least expected it."

Richard, seeing the wisdom of these precautions, did not reply; he examined the lock of his gun, and, having told Darius to keep close to him, he went after Elephant-Slayer and Boa, who had already followed the dog into the wood.

Instead of keeping his nose close to the ground, as hounds generally do, he held his head up and sniffed from time to time. Several times he was just going to bark, but a push at his collar from Boa always put a stop to such dangerous intentions.

He entered the forest at a point where the trees were very thick, and where to all appearance it was perfectly impossible for a human being to follow. But Boa, as if he wished to justify his surname, glided behind the dog and disappeared in silence among the thorny shrubs. The other hunters discovered a less difficult passage, though even there they could only crawl in one by one. At some distance from the edge of the forest the trees did not grow so close to one another, and were less vigorous from the want of air and sun. Still they made little way, and so great were the difficulties, that at the end of half-an-hour they were not more than five or six hundred paces from the great bombax.

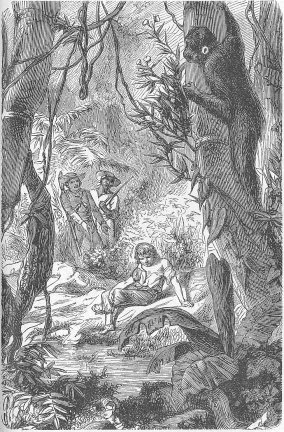

They soon found themselves in a glade filled with rugged blocks of basalt piled up without any order. Tree-ferns and gigantic grass, which seemed to belong to the vegetation of the antediluvian period, partially concealed these picturesque rocks, in the clefts of which some of the lovely flowers were growing that we cultivate at great expense in our hot-houses. Around this spot immense creepers were hanging in festoons from the palm- trees, ebony-trees, pines, and casuarinas, and formed innumerable arches of verdure; a few of the trees had been blown down, some by the recent storm, others by the storms of former days, or they had fallen from age; but they were all buried beneath a mass of climbing plants and those splendid parasitic orchids that grow on old trunks. A few birds of all the colours of precious stones, parroquets, humming-birds, woodpeckers, flew about round these sweet flowers, still wet with rain, and a sweet smell filled the air, such as is often noticed in gardens after a storm.

At this spot the dog quickened his pace, wagged his tail violently, and would have barked if his master had not stopped him by pulling his leash roughly. But while he watched the hound, Boa gave his companions a sign to be on their guard, and got his own gun ready.

Everything proved that the child and his captor were not far off, and it became more and more necessary to be prudent. The orang had perhaps perceived the hunters; possibly he was already hiding in some lurking-place with his terrible club. They were obliged to keep a constant look-out on the right hand and on the left, and they examined the foliage above them incessantly, for death might fall upon them like a thunder-bolt.

The hunters, wading through the high grass, and surmounting a thousand obstacles, listened to the slightest movement, to the least noise. A leaf blown about by the wind, a woodpecker knocking its beak against a bit of rotten wood, a little monkey playing among the creepers, made them turn their heads quickly and stop, till they had discovered the cause of their alarm. They were absorbed in this important examination, when Boa, who was a few steps in advance, stopped all at once, and, resting the butt-end of his gun on the ground, made a sign to them to approach. They hastened to him, and, reassured by his calm attitude, they relaxed their vigilance a little. At the foot of an enormous rock which jutted out, was a rather deep recess, where several persons might have found shelter during the storm of the preceding night. Now it was plain that this kind of niche had been occupied recently; a great quantity of dry moss formed the bed, large pine-leaves had been brought there to serve for a covering. The remains of some cocoa-nuts and several other wild fruits were scattered about, as if to prove that those who had sought a temporary retreat under this rock had not left without having breakfasted.

"Here the orang --- there, Edward."

Elephant-Slayer and Darius seemed convinced of the truth of this remark, but Palmer seemed to doubt it.

"Impossible!" he said: "here we are not more than half a mile from the great bombax, at the foot of which we halted yesterday evening. If my child and this horrible ape had spent the night in this place, they must have heard our shouts, and Edward would certainly have answered."

"And the wind and the rain!" said the Malay. "But master will see."

At the same minute he loosened his hold on the dog, which began eagerly to smell the bed of moss. Very soon the sagacious animal, as if he wished to confirm Boa's assertions, drew from uuder the leaves a little piece of stuff which Richard, with tears, recognised as having formed part of his child's dress.

"It is true, then, that the orang has spared his life!" he cried.

"But look closely, my good fellows: do you see anything to show that Edward is ill, or wounded?"

The Malays again examined the moss bit by bit; they could see no trace of blood, and among the remains of fruit scattered round the rock they found several that, without any doubt, had been nibbled by a smaller and more delicate mouth than that of the wild man of the woods. They concluded from these different circumstances that not only Edward had no serious wound, but also that, in spite of the terror he must have felt, he had not lost his appetite.

"But, then, where is he?" asked Palmer anxiously.

"Not far off," replied Boa; "the bed is still warm. No noise." Already the dog had left the hollow of the rock, and was prowling about with his nose on the ground, as if he had found a regular track. There was reason then to believe that the child, on leaving the spot where he had spent the night side by side with his savage guardian, had been ~lowed to walk, and that if they followed the track patiently they might succeed in finding him. However, this hope was not of long continuance. The track came to an end when they reached a mass of fallen and decayed trees, such as so young a child could not have climbed over without help, and there it ended abruptly.

At this point, doubtless, the orang had taken Edward in his arms and carried him from tree to tree through the air, the path on the ground presenting too many difficulties for him.

The certainty of this dismayed the hunters; but the Malays, after having examined the place attentively, guessed, with some sagacity, the direction the thief must have chosen. They went round several obstacles in their way, and when they reached a piece of ground where it was more easy to walk, the dog all at once found the track he had lost.

Boa wanted to prove in different ways the reality of this important result; but the hound seemed sure of the fact and hastened his steps, with his nose on the ground as before. In a short time there was no longer any room for doubt: in a spot where the streams of water had left the sand damp, two parallel lines of footmarks were plainly visible; one was that of an enormous foot with the great toe very wide asunder from the rest of the foot, and of a peculiar formation, the other was evidently that of a child. Both looked so fresh that they could only have been made a few minutes ago. Richard could not control his joy.

"My God!" he murmured, raising his tearful eyes to heaven, "wilt Thou indeed in Thy wisdom restore him to us?"

But his companions again begged him to be silent; and it was plain from their anxious looks that, in spite of these more favourable appearances, they did not consider success certain by any means. They set forward again, following now a kind of path that seemed to have been traced by some large animal, an ordinary inhabitant of these solitudes. This path was uncertain and irregular, interrupted frequently by stumps of trees and creeping plants. They could not see more than a few steps before them, and were completely ignorant how far distant they were from the orang and his prisoner. However, the dog showed more and more eagerness, and from moment to moment they hoped to come in sight of them. So the hunters followed Boa very cautiously, looking carefully around and with their fingers on the triggers of their guns.

This perseverance was not to be unrewarded. At the end of the path these courageous adventurers entered a part of the forest that was very grand and majestic, and there they found the reward of their labours.

Trees, of prodigious size, growing at regular intervals, supported a triple vaulting of foliage, through which the still feeble, slanting light could hardly penetrate. They might have been taken for the grand pillars that adorn Gothic cathedrals; thousands of years must probably have been required for the wonderful development of these gnarled trunks and roots. There were echoes under this vaulted roof as there are in great buildings, and the chattering, of the parrots that were playing about on the border of this gloomy part, without daring to enter it, was repeated in a very mournful fashion. Through the thick mass of branches and leaves it was impossible to see the least bit of sky; So all the flowering, sweet-smelling plants that require air and light had disappeared, even the parasite strangle weeds and the brilliant-coloured orchis that grows everywhere in the Sumatran forests. Nothing grew on the ground but yellowish lichens, mixed with fungi, and other cryptogamic plants of odd shapes, lovers of damp and darkness.

Now, in the pale light that just penetrated the depths of the forest, the hunters at length discovered two shadows, moving about a hundred paces before them; their practised eyes were not slow in recognising the orang and Edward. The man of the woods, made conspicuous by his great height and long arms, was advancing slowly, leaning on a stick, that served him at once for support and defence. At his side Edward, without a hat and with his clothes torn, was walking listlessly, sobbing incessantly, as naughty children do who are tired of crying; these sobs, repeated by the echo, made a constant, melancholy murmur that it was heart- breaking to hear. However, the man of the woods did not appear to be ill-treating his little companion in any way; on the contrary, he seemed to be very careful of him. He stopped every now and then to wait for him; the child's hands were still full of wild fruit and edible berries, that his captor had gathered for him from the trees they passed. The orang seemed to take pains to spare him all fatigue, and to save him from all danger; he often stroked his back in a caressing way. The affection he so evidently felt for him rendered the hunters enterprise the more perilous; for it was plain the orang would not give up the prey that was so dear to him without a fight.

It was necessary to decide what to do at once; the orang and the child were going further away; and it seemed equally impossible to pursue them openly or to surprise them on this piece of bare ground. Palmer and his men threw themselves flat on the ground, behind a forsaken ant-hill, and Boa hastened to muzzle his dog, whose services were not required just then; and, while one of them kept an eye on every movement of the orang, the others set themselves to deliberate.

A plan was soon agreed upon. They decided that Palmer and the negro should continue the pursuit straight on, gliding from tree to tree, and using every precaution not to be noticed by the suspicious animal; meanwhile Boa and Elephant-Slayer were to try, by going a little way round, to reach, before the orang did, a clump of cocoanut-trees, situated at some distance, towards which he and his little captive were directing their steps; thus the orang would find himself hemmed in, and they might be able to rescue Edward. This plan presented many difficulties, but it was the only practicable one, and they set to work at once to put it into execution.

The Malays retraced their steps for a little way, and, then plunging into the bushy thicket, were not long in disappearing. On their part, Richard and Darius lost no time; they went forward, stooping and taking advantage of every obstacle in the way to hide themselves. The mosses and lichens, with which the ground was covered, favoured this manouvre, for they deadened the sound of their footsteps. On getting near enough to shoot, they were to fire at the orang without waiting for their companions; but it would not do for them to be in too great a hurry, or to fire from too great a distance; for, in that case, they ran the risk of hitting the child, or of only slightly wounding the orang, which would certainly make him more formidable still.

In spite of their efforts they gained very little ground on the two they were pursuing. Every minute they were obliged to stop to keep out of sight of the man of the woods, who seemed uneasy, as if his instinct had warned him of the existence of danger. This going backwards and forwards retarded their progress considerably, and made the poor father most terribly impatient.

However, the orang and Edward had reached the end of that part of the forest that might be called the dark part, and they were just coming to the clump of cocoanut-trees.

A dazzling light now shone upon them, and they could be distinctly seen in spite of the distance. All at once they stopped; Palmer was afraid at first that they had taken alarm, but the calm attitude of the orang reassured him. However, this halt was soon explained; the orang lay down on the ground at the edge of a little pool of water, and began to drink as if he was very thirsty; while Edward, more particular, filled his hand with water and carried it several times to his lips to quench his raging thirst.

The moment was a precious one; Richard and the negro, casting aside every precaution, dashed forward. They rushed over the space between them; but Palmer ran much faster than Darius, who, being loaded with heavy baggage, was soon left behind.

Palmer thought no more of waiting, and ran till he was almost out of breath; but he was obliged to stop again. The orang got up and looked around with a frightened look. The planter lay down till his enemy should go on his way again; he was trembling with anger, and squeezed his gun convulsively in his hands; but he was too far off to venture to fire. Then followed a few minutes of intense anxiety. Would the orang continue to walk with the child, or would he carry his prey into the trees and proceed in what seemed to be his favourite mode of travelling? Chance, or rather Providence, ordered things better than Palmer could have hoped.

The cocoanuts, at the foot of which was the pool of water, were loaded with beautiful-looking ripe fruit. The orang, with that suddenness of determination that distinguishes the quadruman, threw down his club and began to climb one of the trees with the evident intention of gathering some of the nuts. The child remained alone at the edge of the water, but, not knowing where to go, he was obliged to wait for his conductor, and sat down on the ground, still crying quietly.

Richard was already within a short distance of his son, and was able to notice certain heart-rending particulars that had escaped him till then. The poor little fellow's clothes were in tatters; his eyes red and sunken, and his pale, wearied face as well as his hands were furrowed with scratches, from which the orang, in spite of all his care, had not been able to preserve him. In his attitude there was a dejection, a sadness, a despair, that no words could express; yet, with the curiosity of his age, he watched the movements of his captor in the neighbouring tree, or looked absently at the cocoanuts falling with great noise into the pool of water.

Richard was convinced that his son's rescue was certain. Before the orang had come down from the tree, Edward would be safe under his father's protection. The planter, breathless and almost wild with joy, stretched out his hands to him, and, as the child was still looking at the top of the tree, he cried to him in an almost inaudible voice:

"Edward! my dear little Edward!I"

"Massa Edward!" cried Darius, in his turn.

This time the child heard; he turned his head quickly.

Recognising his father and Darius, a smile of indescribable joy overspread his face. He rose quickly and began to run to them, crying:

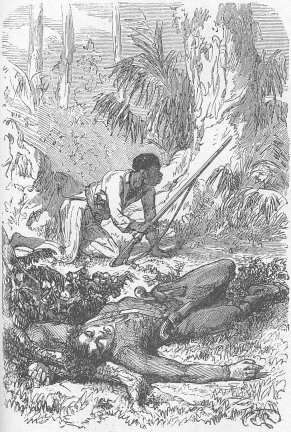

"Oh, papa, dear papa, I knew you would come and help me!" But these imprudent exclamations and unguarded movements ruined everything. As the father and son were on the point of rushing into one another's arms, a kind of hairy phantom threw itself between them, uttering a hoarse guttural cry.

Palmer and Darius, who had followed him closely, were thrown down in spite of their strength and before they had time to think.

At the same time the orang, for it was he that had dropped thus suddenly from the top of the cocoanut-tree, seized the poor child, who struggled and cried piteously; then, taking hold of the trunk of a neighbouring tree, he climbed to the top with incredible rapidity and disappeared once more.

For a moment yet a voice, growing weaker and weaker and more distant, cried out among the leaves:

"Papa! help! Oh, papa, papa!"

Darius fetched a little water from the pool near, and poured it on Richard's face, but it was some time before Palmer came to himself; and, when he did open his eyes, he looked round wildly, and hardly seemed to know where he was.

"Ah, massa!" said Darius; "it have been very lucky that the man who does not speak had not got his club, or we be killed on the spot. Now you drink this." And he held out to him a gourd full of rum. Richard swallowed a few drops, and then his memory seemed to return.

"And Edward? Where is Edward?" he asked abruptly.

Darius reminded him of the sad truth.

On learning that Elephant-Slayer and Boa had already started in search of the orang, Richard exclaimed:

"I must go after them at once! I will not leave to others the task of saving my son! poor little fellow, he was looking out for me, counting on my coming, and calling to me to help him!"

He tried to rise; but no doubt the shock he had received had injured some vital part, for he fell back directly.

"Master, you not well yet," said the negro affectionately, "you wait here and rest. The Malays come back soon, and then all together we go and look for Massa Edward."

Palmer was obliged to yield to his fate; but, overcome with the feeling of his powerlessness, he hid his face in his hands and shed many tears.

At the end of about half-an-hour Elephant-Slayer and Boa returned, gloomy and discontented; they had found no trace of the orang, and they had not heard Edward's voice. Palmer asked them what could be done.

They answered sulkily that the enterprise had failed, and that, according to all appearances, the opportunity that had been lost would not occur again. Now that the wild man of the woods had been put on his guard, he would run away with his victim, without stopping a minute, and would not put a foot to the ground till he was a very long way off.

"And you cannot think," said Boa, "how large the forest is. It would take twenty days, thirty days, or perhaps more, to get to the end of it. How then can we find the orang?" And he and his companion concluded that they must leave Edward to his fate, and go back to the colony. The feeling of indignation gave Palmer new strength.

"What!" he said, leaning on his elbow, "shall I give up the hope of saving my child the very first day, the very first hour? Shall I give way thus to the first obstacle? I thought Elephant-Slayer and Boa were bolder, more used to fatigue; but they are tired and disheartened already; let them go; I must stay alone; I shall not go back."

"Master," said Darius, "me follow you to death." The planter's reproaches offended the Malays. Palmer would have done better to have reminded them of the reward that was promised them in case of success, and he continued:

"The orang will come down to the ground again soon. He seemed to be very fond of my child, and when he sees him out of breath and hurt with these incessant bounds, he will have pity on him, and will leave the top of the trees, I am sure. You know as well, or better than I do, the instinct of these orangs, an instinct that is almost equal to reason!"

"The orangs are men who will not speak," replied Boa, repeating the generally admitted opinion of the Malays; "they have much more reason than some men who do speak."

"God grant they have also a feeling of compassion for weakness," said Richard, sighing. "Now, will you follow me?"

He added everything he could think of to persuade them to continue the search, and though neither of them expected any good results from a fresh attempt, they announced that they were ready to start.

By a strong effort of will, Richard managed to get on his feet without Darius's help. He tottered, and had frightful pain in his head, but he concealed his sufferings, for fear of discouraging his companions still more.

They returned to the pool of water on the border of which the catastrophe had taken place. The Malays examined the spot carefully, made the dog scent the quite recent trace of the child and his captor, and, after they had settled their plans, set out again.

On they went for a long time; on --- on till evening, getting deeper and deeper into the solitary forest. As they proceeded the forest grew more and more wild, and they entered parts that had certainly never been trodden by any human creature before. Sometimes they met wild beasts, which fortunately did not dream of attacking the little band; and they, on their part, took care not to irritate them. They only spoke in monosyllables and in a low voice; they took care not to make any noise, and stopped occasionally to listen in these silent and majestic solitudes. But they heard nothing more either of the orang or Edward; and they could not discover any trace of them. The dog himself, though they frequently gave him the lost child's dress to smell, did not seem any longer to understand what they wanted him to do; and after hunting about for a minute or two to quiet his conscience, went after the track of some deer or other. It seemed certain that if the orang had come down from the tree after the last alarm, he had not done so till he was a long way off, and in some inaccessible place near which the hunters had not chanced to come.

About an hour before sunset, they were all completely exhausted. They had made this journey for the most part on their hands and knees, or else they had had to cut a passage for themselves through the creepers with their cutlasses. Long thorns had pierced through their leathern clothes, some of which were considered poisonous; their hands and faces were torn; thousands of insects, eager for blood, mosquitoes, gnats, and immense wasps, persisted in following them, forming a kind of buzzing cloud around them. Besides, during the day they had not been able to stop for any meal, and had contented themselves with eating some fruit gathered from the trees of the forest; they were now extremely hungry, and their hunger was partly the cause of their extreme prostration.

But none of them were in such a deplorable condition as Palmer, the leader of the expedition. His excessive fatigue and his agony of mind had aggravated his sufferings, till they were almost unbearable. A burning fever consumed him: at times a thick mist came over his eyes, and he could hardly see his way; at others his mind was confused, and he neither knew what he wanted nor where he was going. So that, towards the end of the day, in spite of his courage, he was obliged to lean on Darius to get on at all, and without the help of that devoted negro he would have been left behind long before.

The necessity of finding some shelter for the night was now urgent. The Malays themselves could not tell where they were; all day the sky had been covered with clouds, and then the trees were so thick that they found it impossible to guide themselves by the position of the sun. They only knew that they were far, very far, from any human habitation, and they had no choice but to encamp in the middle of the wood. Now, a storm no less terrible than that of the evening before was brewing, and it was time to stop and construct some kind of shelter.

This was not an easy thing to do. They must find an open spot, clear the ground in order to destroy the dangerous insects, build a hut with the branches and leaves, and gather sufficient wood to keep up a fire large enough to frighten away the wild beasts during the night, and these labours seemed very formidable to men half dead with fatigue.

However, when they told Palmer that they must stop he would not hear of it; according to him, there was no hurry; they might still go on, and perhaps at last they would overtake the objects of their pursuit. But the Malays took no notice of his entreaties, and, while the unhappy father was lying stretched on the grass under the charge of the negro, they considered how they might provide for their present urgent necessities.

The place where they had halted did not seem well suited for an encampment. It was a kind of wide path, made by the frequent passing to and fro of a herd of large animals, either buffaloes or elephants; and what should they do if these formidable herds, which go about particularly at night, should burst upon the travellers when they were fast asleep? Besides, the hunters were dying of thirst; they must discover some water. The two Malays went off therefore in different directions to seek some more convenient spot in the neighbourhood. At the end of a few minutes Elephant-Slayer returned without having succeeded, and sat down at a distance from the others to wait for his companion. The latter was not long in returning, escorted by his dog, who was now allowed to roam at liberty. Doubtless Boa had been more happy in his search, for he simply said:

"Come, all of you."

Elephant-Slayer followed him without asking any explanation; but it was not so easy for Richard to obey the summons. In this short interval of rest he had grown heavy with sleep and could not rise. However, with Darius's help he managed to get on his feet, and dragged himself along behind the rest, uttering groans that were wrung from him by the frightful pains he was enduring.

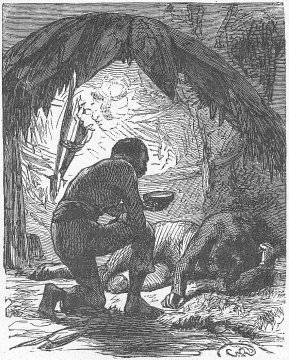

They proceeded about a hundred paces in this way. Boa had chosen a glade surrounded with gigantic trees for a place of encampment. There was a pond in the middle filled by the rain of the preceding night, yet the water was both limpid and fresh. But what struck the hunters most was the sight of three or four huts made of boughs and covered with leaves, fixed on some large projecting roots. These huts, without doors or windows, and constructed in a very rough fashion, were a great help to people who had neither time nor strength to build others. One of them was perched on a pandanus-tree in the fork of two branches, like the nest of an enormous bird. But this style of building was not at all peculiar in a country where the greater number of the dwellings are built on piles, as we have seen was the case with the Malay houses of New Drontheim. Palmer, though almost exhausted with fatigue and suffering, examined these singular constructions with curiosity.

"How could human beings," he said, with an effort, "establish themselves in these melancholy solitudes?"

"Not men from the colonies," answered Boa shortly, "but men who do not speak."

"What!" cried Palmer; "these huts have been built and occupied by orangs?"

The two Malays answered in the affirmative.

"Then let us stay here; the inhabitants of these cabins will certainly return, and perhaps the one that has stolen my son will be among them."

But Boa made them notice that the huts appeared to have been deserted for a long time. The palm-leaves with which they were roofed were crumbling to dust; the heaps of moss that served for a bed inside were swarming with centipedes, wood-lice, scorpions, and other venomous creatures. The remains of cocoa-nuts were scattered about in plenty, but they were rotten and decayed. One of the clubs that apes of a large kind carry had been left in the principal hut, and looked as if it had been there for a year. In fact, there was no reason to hope that these huts had been visited lately by the old proprietors. However, it was necessary to establish themselves there for the night; the storm was rising, the sky was growing darker and darker; there was not a minute to lose. Boa busied himself in covering two of the huts with fresh leaves, and put fresh moss instead of that full of insects. On his part Elephant-Slayer set himself to pile up a supply of dry wood and to cut down the grass round the encampment.

These different labours, thanks to the peculiar experience of the two Malays, were soon finished. In a short time Richard was settled on a soft bed in the principal hut. Darius was to remain with his master, while Boa and Elephant-Slayer occupied a hut near. The Malays and the negro had agreed to watch by turns during the night.

They made a good supper round the fire, which just then had the double advantage of giving light to the hunters and driving away the mosquitoes. As to Richard, though he had taken nothing since the evening before, he could only swallow a few drops of the milk of the cocoa-nut which the negro brought him. He had fallen into a kind of stupor, and, panting for breath, with his eyes closed, he constantly uttered involuntary groans.

The report of the gun and the howling of the monster were so blended with the roaring of the tempest that the sleep of the other hunters was not even disturbed. Only when Boa went in the morning to see what effect his shot bad produced, he found under the brushwood large stains of blood that the pouring rain had not completely effaced; no doubt some royal tiger had experienced for the first time in his solitude the dominant power of man.

At daybreak the Malays and the negro, being rested and in good health, were quite ready to resume the search. Unhappily, the leader of the expedition was no longer in a condition to direct or even to be of any use to his companions. His flushed countenance and wild eyes proved the progress of fever; they called him, but he did not seem to hear; they tried to put him on his feet, but he fell back like a senseless lump. They pressed him with questions, but he only answered with inarticulate sounds; he could no longer think, feel, or understand. What was to be done? Boa and Elephant- Slayer, as hard-hearted towards other people as they were careless of themselves, wanted to leave the sick man to his fate; they talked of returning to the colony, leaving Palmer and the negro to do what they could. But Darius employed all his eloquence to persuade them to abandon such a selfish intention; he reminded them particularly of the express injunctions of the Governor; he told them that if they abandoned "Massa Palmer" in this way the Major would have them hung or shot as soon as they appeared in New Drontheim: in fact, he employed such arguments that the Malays at last became more tractable.

It was agreed that they two alone should follow the track of the orang during the day that had just begun, while Darius remained in the hut with the sick man. Slayer and Boa were to return in the evening, after beating the surrounding parts of the wood; and, if their investigations were in vain, they would consider about returning home the next morning. No doubt Palmer, after having enjoyed absolute rest, would recover his consciousness, and would be able to say what he wished. This plan settled, one of the Malays climbed a tree to see where they were, and that they might be able to find the huts again later in the day. After making his observations, he rejoined his comrade, and they both plunged once more into the wood, followed by the hound.

Darius now remained alone with his master, and the day seemed to him interminable. It continued to rain heavily, though the storm had ceased, and the water was trickling through the roof of the hut. The sick man did not seem to mind it; on the contrary, he placed his burning forehead mechanically under the little stream of water that was dripping down drop by drop, and it appeared to relieve him. He did not speak a word to Darius, and hardly seemed to know him; but at times he got much excited, and in his delirium talked in a most heart-breaking manner. Sometimes he thought he saw his son, and lavished the most tender caresses on him; sometimes he called his dear Elizabeth; and began to comfort her in the most affectionate way. Joy, hope, and terror, seemed to bring gentle or terrible forms before his troubled mind by turns.

Then, exhausted by these violent attacks, he sank again into a state of gloomy torpor, which lasted till the next fit of delirium came on.

In the evening the two Malays returned, very tired and wet to the skin. They had not seen the orang, and had given up all hope of finding poor Edward again. They could not think of penetrating further into these endless forests. They had been attacked by one of the black bears that feed upon palm-trees, and after having fired both their guns at him and wounded him, they put an end to him with their krises.

Then one of them had been pursued by a buffalo, and had been obliged to double to escape the ferocious animal. And, lastly, a few leagues from the huts there was a large swamp full of crocodiles and great snakes, and this appeared to be an insuperable barrier. Slayer and Boa had walked along its edge for a long time without finding any way across, and, to all appearance, no such way existed. It was therefore desirable to begin the retreat at once; especially as the rainy season, which had just commenced, might, if they waited too long, render their return very difficult and very dangerous, if not impossible.

These reasons were decisive, and Darius had nothing to answer, except that his master was quite incapable of walking. However he wished to wait till the next day, before he came to any definite decision, hoping that Palmer's condition would improve in the night.

But the night was still more distressing than the previous one. The sick man tossed about incessantly, and at times his delirium almost amounted, to frenzy. On the other hand, the rain still continued to fall, and threatened to inundate the country. During this night again they had not been able to light any fire, and tigers prowled about continually, roaring frightfully. They were obliged to keep a good lookout and to fire their guns from time to time to drive them away, so that when the first rays of light appeared not one of the hunters had had a moment's rest.

Yet they had need to recruit their strength for the fresh exertions that were awaiting them. There was now, indeed, no doubt what must be done; it was plainly necessary to abandon the child to his fate and return to the colony without loss of time. The provisions were completely exhausted, and they had nothing to depend upon but the wild fruits of the forest.