Classical Images of Edgar Rice Burroughs

Part I by Alan Hanson

Tarzan and John Carter are the literary blood brothers

of Odysseus, and Edgar Rice Burroughs is the incarnation of Homer. So it

is that Erling B. Holtsmark would have us believe. In his two books, “Tarzan

and Tradition” (1981) and “Edgar Rice Burroughs” (1986), Professor

Holtsmark contends that Burroughs patterned, plotted, and packaged his

stories in the format of classical mythology. To the average Burroughs

fan, the good professor’s arguments range from convincing to far-fetched

to unfathomable.

Though Holtsmark’s discussion may be beyond the comprehension

(not to mention the interest) of the blue collar Burroughs reader, even

those who read ERB only for escape purposes, must realize that the author

did indeed have extensive knowledge of Greek mythology. His works are riddled

with dozens of references to “Herculean strength,” Stygian darkness,” “Titantic

struggles,” and the like. These images, and there are several hundred of

them scattered throughout ERB’s works, are indicative of wide-ranging classical

knowledge. References are there to the mythological story of creation;

to the many Greek gods, both the greater and the lesser; to the often told

stories of love and adventure; to the great heroes before the Trojan War

and on down through the time of Homer and the wanderings of Odysseus.

Leaving plotting and patterns to Professor Holtsmark,

it is the purpose here to look at Edgar Rice Burroughs’ use of specific

mythological terms and characters in creating images in his stories. ERB

used these images usually to make comparisons and to give color to his

settings. These images will be surveyed in mythological order, from the

dawn of creation down to the time of Odysseus.

Creation

The mythological story of creation consists of many stories,

some of which contradict others. Two of the characters from the early days

most well known to the Greeks were Prometheus, one of man’s greatest benefactors,

and Pandora, one of his greatest curses. Although he was a Titan, Prometheus

sided with Zeus and his brothers in their war of supremacy with the Titans

led by Cronus. After their victory, Zeus and the other gods of Olympus

delegated to Prometheus the task of creating mankind. Prometheus had little

to work with, however, for his short-sighted brother, Epimetheus, had already

created animals and given them all the best gifts—strength, swiftness,

courage, cunning, wings, and fur to protect them from the cold. To make

man superior, however, Prometheus gave him an upright shape like the gods

and brought him a torch lit at the sun to provide fire, a protection far

better than any animal had.

In “Lost on Venus,” Burroughs made a rather extended

reference to this benefactor of man. Wandering lost in a wild land, Carson

Napier realized that his greatest handicap to survival was his lack of

Prometheus’ gift. He sought to get it by futilely rubbing two sticks together.

When Duare asked the frustrated Carson if he were going to give up, he

responded, “Of course not. It’s like playing golf. Most people never learn

to play it, but very few give up trying. I shall probably continue my search

for fire until death overtakes me or Prometheus descends on Venus as he

did on Earth.” Duare asked, “What is golf and who is Prometheus?” Carson

replied, “Golf is a mental disorder and Prometheus is a fable.” When sparks

suddenly flew to start his fire, Carson exclaimed, “I apologize to Prometheus.

He is no fable.”

Zeus was so upset that Prometheus had treated mankind

so well that he swore to get revenge on humans. He sent a great evil for

man in the form of a lovely and sly maiden named Pandora, from who sprang

the race of women. The gods presented Pandora with a box but forbade her

to open it. Of course, her curiosity caused her to lift the lid, and out

flew plagues, sorrow and misery for mankind. The box was not entirely a

curse, however, for from it also emerged Hope, which would be man’s only

comfort in times of misfortune.

In “The Moon Maid,” Julian 3rd must have felt both

misery and hope as his off-course ship approached the moon, for at that

time he made reference to the myth of Pandora. “I presumed that one of

the greatest thrills that we experienced in this adventure, that was to

prove a veritable Pandora’s box of thrills, was when we commenced to creep

past the edge of the Moon and our eyes beheld for the first time that upon

which no other human eyes had ever rest upon—portions of the two-fifths

of the Moon’s surface which is invisible from the Earth.”

Cimmerian Darkness

The Greeks believed that the newly created mankind emerged

on the Earth forged in the shape of a round disc, around which flowed the

river Ocean. On the farther bank of Ocean was a misty, cloud-shrouded land

hardly ever visited. Here lived the Cimmerians, who knew only perpetual

night, for the sun never shone upon their land. From these melancholy people,

Burroughs drew the term “Cimmerian darkness.” It is a term more descriptive

of a gloomy mood that it is indicative of intense darkness. For instance,

in “Tarzan the Untamed,” after Xujans captured Tarzan, Bertha Kircher,

and Lt. Percy Smith-Oldwick, ERB used the term to reflect the captives’

state of mind as they were led through the forest. “Once beneath the over-arching

trees all was again Cimmerian darkness, nor was the gloom relieved until

the sun finally rose beyond the eastern cliffs.”

Another gloomy captive was James Blake in “Tarzan,

Lord of the Jungle.” As he was being led through a rocky tunnel toward

an unknown destination, the depression brought on by the absence of sunlight

set upon him. “Even the haunting mystery of the long tunnel failed to overcome

the monotony of its unchanging walls that slipped silently into the torch’s

dim ken for a brief instant and as silently back into the Cimmerian oblivion

behind to make place for more walls invaryingly identical.

Still another captive who knew the gloom of Cimmerian

darkness was John Carter. In “The Gods of Mars,” during the monthly

rites of Issus in the depths of Omen, the warlord toppled into a pit behind

the throne of Issus. A polished chute deposited him in a dimly lit room

far below the arena above, and there an angry Issus addressed him from

outside heavy bars. “Rash mortal! You shall pay the awful penalty for your

blasphemy in this secret cell. Here you shall lie alone and in darkness

with the carcass of your accomplice (Carthoris) festering in its rottenness

by your side, until crazed by loneliness and hunger you feed upon the crawling

maggots that were once a man.” Following this unpleasant condemnation,

John Carter told the reader, “That was all. In another instant she was

gone, and the dim light which had filled the cell faded into Cimmerian

blackness.” It is another example of Burroughs using the term “Cimmerian”

to signify not only the absence of light, but also fading of light from

a captive’s spirit.

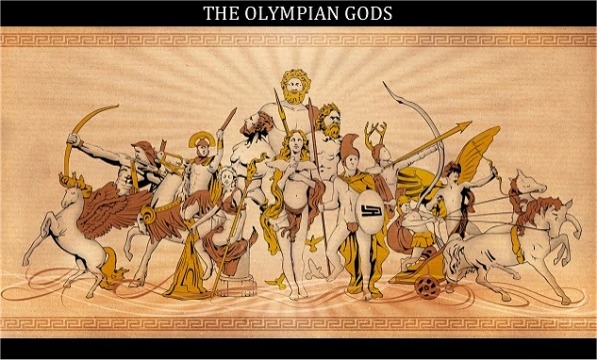

The Olympian Gods

The Greeks had many, many gods, but supreme among them

were the 12 great Olympians, who ruled Earth from their peaceful mountaintop

above the clouds. In the following list, the Latin name for each god is

in parentheses after the Greek name. ERB usually used the Latin versions.

The divine family included Zeus (Jupiter), the leader; his to brothers,

Poseidon (Neptune), ruler of the sea, and Hades (Pluto), king of the underworld;

their sister Hestia (Vesta), Goddess of the Hearth and Home; Hera (Juno),

Zeus’ wife; their son Ares (Mars), God of War; Athena (Minerva), Goddess

of the City; Apollo (Apollo), God of Light and Truth; Aphrodite (Venus),

Goddess of Love; Hermes (Mercury), messenger of the gods; Artemis (Diana),

the huntress; and Hephaestus (Vulcan), the God of Fire.

In his fiction, Edgar Rice Burroughs mentioned half of

the Olympians by name. Tarzan was compared in appearance to two of them.

In “Tarzan the Invincible,” Nkima “rode upon the shoulder of a bronzed

Apollo of the forest.” Again, in “Tarzan and the City of Gold,”

Tarzan is described as, “tall, magnificently proportioned, muscled more

like Apollo than like Hercules.” However, the best description of Tarzan

in mythological terms, appears in “Tarzan and the Golden Lion.”

“Not as the muscles of the blacksmith or the professional strong man are

the muscles of Tarzan of the Apes, but rather as those of Mercury or Apollo,

so symmetrically balanced were their proportions, suggesting only the great

strength that lay in them. Trained to speed and agility were they as well

as to strength, and thus, clothing as they did his giant frame, they imparted

to him the appearance of a demi-god.” A demi-god is literally the offspring

of a god and a mortal, but more likely ERB was trying to suggest here that

the ape-man had an aura of god-like qualities in his appearance.

Other than these descriptions of Tarzan, ERB’s references

to

the Olympian gods is confined to his two novels set in Roman societies—“Tarzan

and the Lost Empire” and “I Am a Barbarian.” In the Tarzan novel,

only Jupiter is mentioned, and then only in exclamations, such as “By Jupiter,”

“May Jupiter strike me dead,” and If you were the son of Jupiter himself.”

In “I Am a Barbarian,” more substantial images of the gods appear.

To justify his decision to marry his own sister, the mad Caligula cited

the precedent set by the leader of all the gods. “It is only fitting that

it should be thus,” explained Caligula, “since a god is to wed a goddess,

even as the great Jupiter wed his sister, Juno; and who can deny the divinity

of the Julian family?” Later, Caligula, who imagined himself no less divine

than the Olympians, took to communicating directly with the mighty god.

“Often he pretended he was conversing with Jupiter, and, after speaking

at length, he would cock his head on one side and listen to the god’s reply,

pursing his lips and nodding his head in simulation of complete understanding.

At such times he would often get into violent arguments with Jupiter, ending

up by threatening the god with annihilation.”

While never carrying through with his threat against Jupiter,

Caligula did claim a battlefield victory over one of the great god’s brothers.

To the bewilderment of his admirals, Caligula had them line up all the

ships of their fleets to form a bridge. When the road was completed, Caligula,

“rode across it in full armor, followed by troops with their standards,

proclaiming that he had conquered an enemy—Neptune!” Later, on the coast

of Gaul, Caligula ordered his army to gather the spoils of war. When his

generals seemed confused, the emperor screamed, “The shells! The shells!

The treasures of Neptune, who has defied me!”

Ironically, Caligula was also closely aligned with Venus,

the Goddess of Love. The Julian line, from which Caligula sprang, took

great pride in the fact that their family was supposed to have been descended

directly from the Goddess of Love. However, the slave Britannicus spoke

critically of this relationship. “But why that have been anything to boast

of, I do not know. Had I been descended from Venus, I should have kept

the matter very quiet. She had been a notoriously loose woman, appalling

promiscuous.” Britannicus may have been thinking primarily of Venus’ affair

with Mars as described in the “Odyssey.” Her husband, Vulcan, caught them

together in his own bed and trapped them there with a net until Poseidon

promised to compensate him for the wrong that his unfaithful wife had done

him.

Lesser Gods and Mortals

Beneath the great Olympians were dozens of lesser gods,

such as Demeter, Dionysus, Eros, Pan, and Iris. With one exception, Burroughs

chose to ignore these lesser gods in his fiction. The one exception was

Morpheus, the son of the God of Sleep. The abode of Sleep was near the

dark land of the Cimmerians, and the only sound heard in his valley was

the gentle flowing of the river Lethe, the river of forgetfulness. When

the gods wished to communicate with a human, they would contact the God

of Sleep, who would rouse and send for his son Morpheus to manipulate mortal

dreams.

Burroughs used the image of Morpheus a couple of times.

At the beginning of Part 2 of “The Mad King,” Barney Custer heard

a conservation going on in a room next to his at a Serbian inn. “Barney

paid only the slightest attention to the meaning of the words that fell

upon his ears, until, like a bomb, a sentence broke through his sleepy

faculties, banishing Morpheus upon the instant,” reported ERB. What Barney

heard was Peter of Blentz and others plotting the demise of King Leopold

of Lutha. On another occasion, Edgar Rice Burroughs, the narrator (as opposed

to the author), might have suspected he was entertaining Morpheus. It happened

on the night that Carson Napier’s vision startled the author out of a sound

sleep at his Tarzana home in “Pirates of Venus.” Although not prone

to hallucinations, Burroughs could not convince himself that he had dreamed

of the ghostly figure and the words she spoke. “In fact I was so wide awake,”

wrote Burroughs, “that it was fully an hour before I successfully wooed

Morpheus, as Victorian writers so neatly expressed it, ignoring the fact

that his sex must have made it rather embarrassing for gentlemen writers.”

On the whole, rather than the Greek Gods, ERB was more

fond of using images of the great mortal heroes, such as Jason and Hercules,

and their stories of love and adventure. One of the earliest of such stories

was of Io and Argus. The maiden Io had the misfortune of having the great

god Zeus fall in love with her, and when Zeus’ wife Hera was about to catch

them together, Zeus disguised Io by changing her into a lovely white heifer.

Hera was not fooled, however, and asked her husband to give her the heifer

as a present, a request that Zeus could not deny, since a refusal would

be admitting the affair to his wife. Hera knew that Zeus would try to retrieve

the heifer, and so she put Io under the care of Argus, the great watchman.

Argus had 100 eyes, and while many of them would close in sleep, there

were always some that remained open, making Argus a symbol of eternal vigilance.

Burroughs used this image to point out an analogous situation

in his story “The Rider.” Ordinary American Hemmington Main sought

the hand of Miss Gwendolyn Bass, daughter of multi-millionaire Abner Bass.

While the girl was willing enough, her mother was determined that her daughter’s

marriage bring a title into the family. In search of such a title, Mrs.

Bass took her daughter to Europe, where their travels finally brought them

to Demia, the capital city of Margoth. Main had followed them there, and

in Demia he met M. Kargovitch, who offered to help Main. The American explained

his predicament in mythological terms. “Gwendolyn would marry me in a minute,”

Main lamented, “if we could get her away from her mother long enough to

have the ceremony performed; but mama has Argus backed through the ropes

in the first round when it comes to watchfulness.” After Kargovitch came

up with a plan to have the marriage performed, he told Main, “Now go and

learn if you can when Argus and Io leave Demia, and the road that they

will take.” Just like Zeus’ plan to retrieve the original Io, the plan

to give Main his Io failed miserably, leaving matters worse than they had

been before.

Another love story to which Burroughs was fond of referring

is that of Adonis. His classic manly beauty wounded the hearts of many

women, even the goddess Aphrodite and the queen of the underworld Persephone.

None would possess him, however, for he was destined to die a mortal death,

gored by a wild boar. Every year the Greek girls mourned his death and

rejoiced at the blooming of his flower, the blood-red anemone.

ERB used comparisons to Adonis to symbolize perfection

of manly beauty. No strength or agility is inferred in his image, just

the perfectly cut and symmetrical physical features that women find irresistible.

In “Tanar of Pellucidar,” for example, Burroughs called Doval of

Amiocap “the Adonis of Paraht. In all Amiocap there was no handsomer youth

than Doval. Many were the girls who had avowed their love for him, but

his heart had been unmoved until he looked upon Stellara.” Unlike the original

Adonis, however, Doval was resistible, as Stellara demonstrated by encouraging

him to win the love of another.

The Adonis of Mars was the Black Pirate Xodar. He is described

as “a handsome fellow, clean limbed and powerful, with an intelligent face

and features of such exquisite chiseling that Adonis himself might have

envied him.” Another Burroughs Adonis is Jimber-Jaw, the prehistoric man

brought back to life in “The Resurrection of Jimber-Jaw.” Pat Morgan,

who found the frozen cave man, used scissors and a safety razor to prepare

him to enter civilization. “The transformation had been astonishing,” recalled

Morgan, “from Man-Mountain Dean to Adonis.” In “The Son of Tarzan,”

Meriem in her thoughts envisoned Korak as a “giant Adonis of the jungle,”

but it is interesting that Tarzan was never described as an Adonis. Rather,

Burroughs chose to compare the ape-man to the less beautiful but more athletic

god Apollo.

The Underworld

The kingdom of the dead in Greek mythology was called

Hades after the god who ruled it. The way to it led across the river Ocean

and over the edge of the world. Erebus was the division of the underworld

into which the dead passed as soon as they died. There to ferry souls of

the dead across Acheron, the river of woe, to the gates of Hades was the

aged boatman Charon. Separating the underworld from the world above were

three other rivers, among them Styx, the river by which the gods swore

their unbreakable oaths.

ERB used several images of the underworld and each carried

the impression of despair and impending doom. In “Tarzan and the Leopard

Men,” Old Timer was being transported downriver by night surrounded

by 30 canoes carrying warriors of the Leopard God. The captive knew not

where he was headed, but it seemed to him like he was passing into the

mythological world of the dead. “The river itself was mysterious,” ERB

noted. “The unwonted silence of the warriors accentuated the uncanniness

of the situation. Everything combined to suggest to his imagination a company

of dead men paddling up a river of death, three hundred Charons escorting

his dead soul to Hell.” Abner Perry believed for a moment that he had actually

arrived in Hades when the prospector first broke through into Pellucidar

in “At the Earth’s Core.” As they gazed upon the unearthly landscape

of the inner world, David Innes asked Perry, “Do you think that we are

dead, and that this is heaven?” The old man pointed to the “iron mole”

and replied, “ But for that, David, I might believe that we were indeed

come to the country beyond the Styx.”

When the dead passed through Erebus, the light of life

passed forever from their souls. ERB used the term “dark as Erebus” to

bring forth the image of such a sudden ending of light faced by some of

his characters. For instance, in “Tarzan and the Forbidden City,”

D’Arnot and Helen and Brian Gregory convinced Ashairian priest Herkuff

to show them a secret trail out of Tuen-Baka. He led them far beneath the

lake down a dim corridor, where a secret, touch opened a doorway in the

lava walls. “Suddenly it swung toward him, revealing the mouth of an opening

dark as Erebus.” In “At the Earth’s Core,” Sagoths escorted their

captives David Innes and Dian as they approached a range of mountains.

“When we reached them, instead of winding across them through some high-flung

pass, we entered a mighty natural tunnel—a series of labyrinthine grottoes,

dark as Erebus.” In another example, Tarzan and Nkima sat upon the roof

of the Temple of the Leopard God in “Tarzan and the Leopard Men.”

After “Muzimo” saw what he was looking for, he “launched himself into the

foliage of a nearby tree, and as The Spirit of Nyamwegi (Nkima) followed

him the two were engulfed in the Erebusan darkness of the forest.”

Stygian Darkness

One particular reference to the underworld, that of “Stygian”

darkness, is the most common of all mythological images in the works of

ERB. “Stygian” refers a likeness to the river Styx, whose black waters

rose on the earth’s surface and flowed down into the underworld. ERB used

the image in several forms, including “Stygian blackness,” “Stygian night,”

“Stygian darkness” and “Stygian gloom.” All were used to indicate intense

and impenetrable darkness.

One place to which Burroughs often referred in terms of

“Stygian” darkness is Tarzan’s jungle. Normally, it is hard to imagine

anywhere on the open surface of the earth where darkness could be so intense,

but considering the absence of artificial light and the denseness of vegetation

ERB described, one can begin to imagine how extreme could be the darkness

along a jungle trail on a moonless night. Consider this description from

“Tarzan of the Apes.” “Here and there the brilliant rays penetrated

to earth, but for the most part they only served to accentuate the Stygian

blackness of the jungle’s depths.” Now try to visualize, feel and even

hear the darkness in this passage from “The Beasts of Tarzan.” “Through

the luxuriant, tangled vegetation of the Stygian jungle night a great lithe

body made its way sinuously and in utter silence upon its soft padded feet.”

Of course, growing up in such an environment, Tarzan’s

very survival depended on adapting to the jungle darkness. In “Jungle

Tales of Tarzan,” ERB tells the reader, “long use of his eyes in the

Stygian blackness of the jungle nights had given to the ape-man something

of the nocturnal visionary powers of the wild things.” On many occasions

in his adult life, this ability to sense through, if not see through, intense

darkness held Tarzan in good stead. For example, in “Tarzan the Terrible,”

when darkness limited the ape-man’s use of vision, his other senses kicked

in to compensate. After making the long journey to Pal-ul-don to find his

lost wife, Tarzan finally heard Jane’s voice coming from a room in the

temple of A-lur. After knocking the iron bars from a window, Tarzan entered

the room to find it plunged into darkness. Still, the ape-man was not helpless,

for his nose could work in the dark as well as in the light. “Again and

again he called (Jane’s name), groping with outstretched hands through

the Stygian blackness of the room, his nostrils assailed and his brain

tantalized by the delicate effluvia that had first assured him that his

mate had been within this very room.”

If Tarzan had the ability to function with little impairment

in “Stygian” blackness, other ERB characters found being thrown into such

darkness a harrowing experience. Take Thandar in “The Cave Girl.”

Toward the end of the story, he and Nadara had been captured by pirates

and put in separate huts. During the night Thandar saw a “huge, dark hulk

of a man” crawling into Nadara’s hut. Thandar followed to save his mate,

and the two men faced each other in a fight to the death in impenetrable

darkness. “Then commenced the struggle within the Stygian blackness of

the interior of the hut … The heavy breathing of the two rose and fell

upon the silence of the night — that and the scuffling of their feet were

the only sounds of combat … At last, with a superhuman effort, the night

prowler broke away from Thandar. For a moment silence reigned in the hut.

None of the three could see the other. For moments that seemed hours the

three stood in utter silence, endeavoring to stifle their breathing.” Thandar,

of course, eventually emerged victorious from the struggle, but the fact

remains that it was only through luck, and that, unlike with Tarzan, the

intense darkness of the situation neutralized any advantage in strength

and cunning Thandar might have had over his opponent in the daylight.

In ERB’s works there is a whole race of people who do

not function well in the intense darkness. They are the Pellucidarians.

In “Tanar of Pellucidar,” when Tanar and Jude escaped from the deep

underground cavern of the Coripies, they made their way down a tunnel in

which the absence of light was absolute. “Groping his way through the darkness

and followed closely by Jude, Tanar crept slowly through the Stygian darkness.”

After an interminable time traveling down the black corridor, the two finally

came to a cavern filled with the subdued light of phosphorescent rock.

There Jude exclaimed, “At least I shall not die in that awful darkness.”

ERB went on to explain the extent of relief in that statement. “Perhaps

that factor of their seemingly inevitable doom had weighed most heavily

upon the two Pellucidarians, for, living as these people do beneath the

brilliant rays of a perpetual noonday sun, darkness is a hideous and abhorrent

thing to them, so unaccustomed are they to it.”

~Concluded in Part II: ERBzine 6618

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()