Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive

Volume 3571

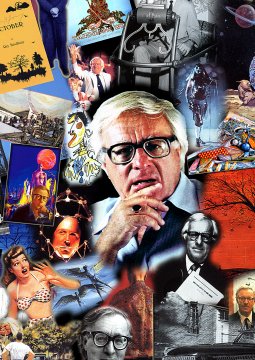

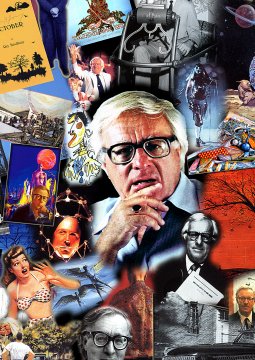

The ERBzine Edgar Rice Burroughs / Ray Bradbury Connection Presents

Tarzan, John Carter, Mr. Burroughs,

and the Long Mad Summer of 1930

By Ray Bradbury

Introduction to The Man Who Created Tarzan by Irwin PorgesIn the summer of 1930 if you had got off a train and walked up through the green avenues of Waukegan, Illinois, you might have met a mob of boys and girls running the other way. You might have seen them rushing to drown themselves in the lake or hide themselves in the ravine or pop into theatres to sit out the endless matinees. Anything, anything at all to escape . . .

What?

Myself.

Why were they running away from me? Why was I causing them endless flights, endless hidings-away? Was I, then, that unpopular at the age of ten?

Well, yes, and no.You see my problem was Edgar Rice Burroughs and Tarzan and John Carter, Warlord of Mars.

Problem, you ask. That doesn't sound like much of a problem.

Oh, but it was. You see, I couldn't stop reading those books. I couldn't stop memorizing them line by line and page by page. Worst of all, when I saw my friends, I couldn't stop my mouth. The words just babbled out. Tarzan this and Jane that, John Carter here and Dejah Thoris there. And when it wasn't those incredible people it was Tanar of Pellucidar or I was making noises like a tyrannosaurus rex and behaving like a Martian thoat, which, everyone knows, has eight legs.

Do you begin to understand why in Waukegan, Illinois, the summer of 1930 was so long, so excruciating, so unbearable for everyone?

Everyone, that is, save me.

My greatest gift has always been falling in love.

My greatest curse, for those with ears, has been the expression of love.

I went to bed quoting Lord Greystoke.

I slept whimpering like Cheetah, growling like Numa, trumpeting like Tantor.

I woke, called for my head, which crawled on spider legs from a pillow nearby, to sit itself back on my neck and name itself Chessman of Mars.

At breakfast I climbed trees for my father, stabbed a mad gorilla for my brother, and entertained my mother with pithy sayings right smack-dab out of Jane Porter's mouth.

My father got to work earlier each day.

My mother took aspirin for precipitant migraine.

My brother hit me.

But, ten minutes later I hit the door, the lawn, the street, babbling and yodeling ape cries, ERB in my hand and in my blood.

How came it so?

What was it that Mr. Burroughs did to several dozen million scores of boys all across the world in the last sixty years? Was he a great thinker?

He would have laughed at that.

Was he a superb stylist?

He would have snorted at that, also.

What if Edgar Rice Burroughs had never been born, and Tarzan with him? Or what if he had simply written Westerns and stayed out of Nairobi and Timbuctoo? How would our world have been affected? Would someone else have become Edgar Rice Burroughs? But Kipling had his chance, and didn't change the world, at least not in the same way.

The Jungle Books are known and read and loved around the world, but they didn't make most boys run amok pull their bones like taffy and grow them to romantic flights and farflung jobs around the world. On occasion, yes, but more often than not, no. Kipling was a better writer than Burroughs, but not a better romantic.

A better writer, too, and also a romantic, was Jules Verne. But he was a Robinson Crusoe humanist/moralist. He celebrated head/hands/heart, the triple H's shaping and changing a world with ideas. All good stuff, all chockful of concepts. Shall we trot about the world in eighty days? We shall. Shall we rocket to the Moon? Indeed. Can we survive on a Mysterious Island, a mob of bright Crusoes? We can. Do we clear the seas of armadas and harvest the deeps with sane/mad Nemo? We do.

It is all adventurous and romantic. But it is not very wild. It is not impulsive.

Burroughs stands above all these by reason of his unreason, because of his natural impulses, because of the color of the blood running in Tarzan's veins, because of the blood on the teeth of the gorilla, the lion, and the black panther. Because of the sheer romantic impossibility of Burroughs' Mars and its fairytale people with green skins and the absolutely unscientific way John Carter traveled there. Being utterly impossible, he was the perfect fast-moving chum for any ten-year-old boy.

For how can one resist walking out of a summer night to stand in the middle of one's lawn to look up at the red fire of Mars quivering in the sky and whisper: Take me home.

A lot of boys, and not a few girls, if they will admit it, have indeed gone "home" because of such nights, such whispers, such promises of far places, such planets, and the creator of the inhabitants of those planets.

In conversations over drinks around our country the past ten years I have been astonished to discover how often a leading biochemist or archaeologist or space technician or astronaut when asked: what happened to you when you were ten years old? replied:

"Tarzan."

"John Carter."

"Mr. Burroughs, of course."

One eminent anthropologist admitted to me, "When I was eleven I read The Land That Time Forgot. Bones, I thought. Dry bones. I will go magic me some bones and resurrect a Time. From then on I galloped through life. I became what Mr. Burroughs told me to become."

So there you have it. Or almost have it, anyway. The explanation that we, as intellectuals, dread to think about. But that we, as creatures of blood and instinct and adventure, welcome with a cry. An idea, after all, is no good if it doesn't move. Toynbee, for goodness sake, teaches us that. The Universe challenges us. We must bleed before the challenge. We must waste ourselves in Time and Space in order to survive, hating the challenge, hating the response, yet in the welter and confusion, somehow loving it all. We are that creature of paradox that would love to sit by the fire and only speak. But the world, other animals more immediately practical than ourselves, and all of outer space says otherwise. We must die in order to live. The settlers did it before us. We will imitate them on the Moon, on Mars, and bury ourselves in graveyards among the stars so that the stars themselves become fecund.

All this Burroughs says most directly, simply, and in terms of animal blood and racial memory every time that Tarzan leaps into a tree or Carter soars through space.

We may know and admire and respect and be moved by Mr. Verne, but he was too polite, wasn't he? You always felt that in the midst of Moon-stalking, his gents might just sit down to tea, or that Nemo, no matter how deep he sank in the Sargasso, still had time for his organ and his Bach. Very nice, very lovely. But the blood does not move so much with this, as does the mind.

In sum, we may have liked Verne and Wells and Kipling, but we loved, we adored, we went quite mad with Mr. Burroughs. We grew up into our intellectuality, of course, but our blood always remembered. Some part of our soul always stayed in the ravine running through the center of Waukegan, Illinois, up in a tree, swinging on a vine, combating shadow-apes.

I still have two letters tucked away in my First Edition Tarzan of the Apes. They were written by Mr. Burroughs to me when I was seventeen and still fairly breathless and in fevers over him. I had asked him to come down and speechify the Science Fiction League which met every Thursday night in Clifton's Cafeteria in Los Angeles. It was a great chance for him to meet a lot of mad young people who dearly loved him. Mr. Burroughs, for some strange reason, cared not to join the mob. I wrote again. This time Mr. Burroughs wrote back and assured me that the last thing in the world he would dream of doing was make a public lecture. Thanks a lot but no thanks, he said.

What the hey, I thought, if he won't talk about Tarzan, I will.

I gabbed and blabbed and gibbered about Tarzan for well over an hour. I had Clifton's Cafeteria emptied in ten minutes, everyone home in twenty, everyone with aspirins for migraine in their mouth five minutes short of an hour.

The summer of 1930 madness had struck again. When I stopped babbling, my arms ached from swinging on all those vines, my head rang from giving all those yells.

I guess that about sums it up.

A number of people changed my life forever in various ways.

Lon Chaney put me up on the side of Notre Dame and swung me from a chandelier over the opera crowd in Paris.

Edgar Allan Poe mortared me into a brick vault with some Amontillado.

Kong chased me up one side and down the other of the Empire State.

But Mr. Burroughs convinced me that I could talk with the animals, even if they didn't answer back, and that late nights when I was asleep my soul slipped from my body, slung itself out the window, and frolicked across town never touching the lawns, always hanging from trees where, even later in those nights, I taught myself alphabets and soon learned French and English and danced with the apes when the moon rose.

But then again, his greatest gift was teaching me to look at Mars and ask to be taken home.

I went home to Mars often when I was eleven and twelve and every year since, and the astronauts with me, as far as the Moon to start, but Mars by the end of the century for sure, Mars by 1999. We have commuted because of Mr. Burroughs. Because of him we have printed the Moon. Because of him and men like him, one day in the next five centuries, we will commute forever, we will go away . . .

And never come back.

And so live forever.Ray Bradbury

Los Angeles, California

May 8, 1975

FOR MORE SEE

Ray Bradbury Remembers ERB

www.erbzine.com/mag37/3734.html#erb

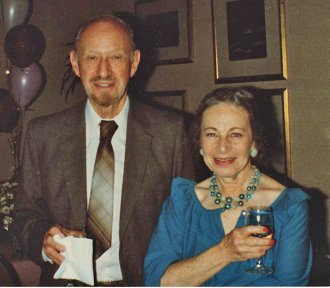

Irwin Porges and his wife Cele |

|

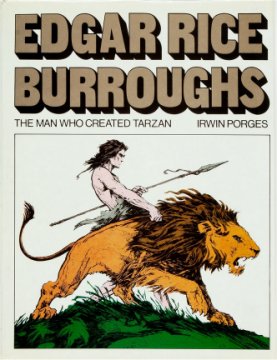

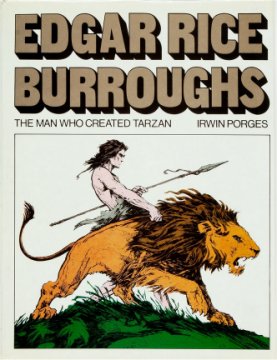

Irwin and Arthur Porges |

Irwin Porges. Brigham Young University Press, 1975. This is an in-depth look at Edgar Rice Burroughs. Born over a hundred years ago, Burroughs is not only the originator of Tarzan, but is also acknowledged as an innovator of American science fiction, and his works are still enjoyed by millions of readers from all parts of the world. The book also takes a look at Burroughs' other-world fantasy and jungle adventure stories, and includes the flavour of his work done in other genre: western stories, mystery puzzles, plays, poems, articles, newspaper columns, photographs and drawings. 820 pages in hard cover.

|

Ray Bradbury Remembers ERB Ray Bradbury 1920-2012: A Life in Photos Wizard From Waukegan Tarzan, John Carter, Mr. Burroughs, and the Long Mad Summer of 1930 Mars Is Heaven!: Graphic Version and Radio Presentation Ray Bradbury's I, ROCKET Illustrated by Al Williamson Ray Bradbury Elsewhere in ERBzine:

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2012/2018/2021 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.