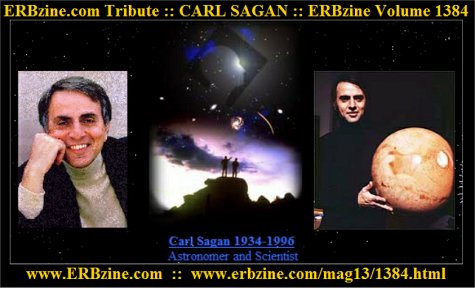

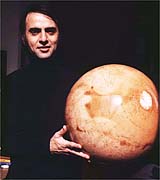

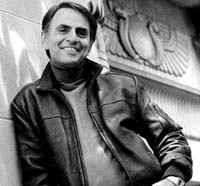

Carl Sagan died Friday, December

20, 1996 in Seattle at the age of 62, of complications arising from bone

marrow cancer.

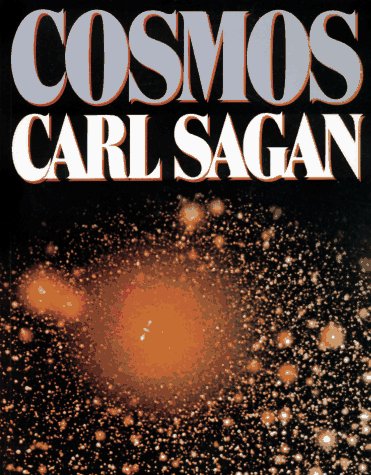

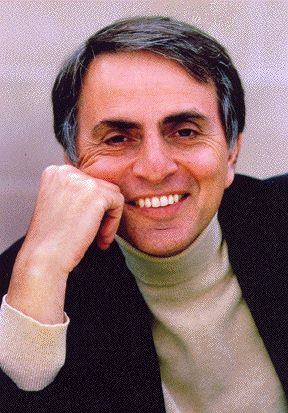

Sagan was the world's best known

astronomer as a result of hosting "Cosmos" a 1980 series on public television

which had an estimated audience of 400 million people. He was a prolific

writer with 600+ papers and articles and a distinguished scientist. Research

interests included the origins of life, nuclear winter, the possibility

of life in other locations in the universe.

His books included:

-

Broca's Brain: Reflections on the

Romance of Science

-

The Cold and the Dark: The World

After Nuclear War (co-author)

-

Comet (with Ann Druyan)

-

Contact (fiction)

-

The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial

Prospective

-

The Demon-Haunted world: Science

as a Candle in the Dark

-

The Dragons of Eden: Speculations

on the Evolution of Human Intelligence

-

Other Worlds

-

Pale Blue Dot

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors:

A Search for Who We Are (with Ann Druyan)

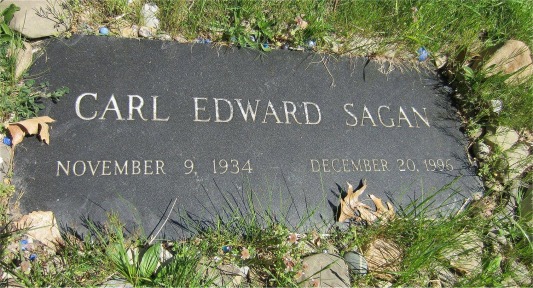

Born: November 9, 1934,

Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, NY

Died: Friday, December

20, 1996, 62 years.

Education: University Chicago,

Ph.D. Astronomy and astrophysics.

Career: Fellowship, University

of California at Berkeley; Assistant Professor of Astronomy at Harvard

University; Professor Cornell. Consultant to NASA, Mariner, Viking and

Pioneer missions.

Positions: David Duncan

Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences; Director of the Laboratory for

Planetary Studies at Cornell University; Chairman, Division for Planetary

Sciences, American Astronomical Society; President, Planetary Society;

Editor in Chief, Icarus.

Honors: Pulitzer Prize,

1978 "The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence;"

Public Welfare Medal, the National Academy of Science; Medal for Distinguished

Public Service, NASA;

Family: Wives: Lynn Margulis

(divorced); Linda Salzman (divorced); Ann Druyan;

Sons: Dorion, Jeremy,

Nicholas, Sam; Daughter: Alexandra. One grandchild. Sister: Cari Sagan

Greene.

IN

HIS OWN WORDS...

"The Cosmos is all that is or ever

was or ever will be. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us

- there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation,

as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching

the greatest of mysteries."

-"The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean," Cosmos, p. 4.

ON

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS:

"I can remember as a child reading

with breathless fascination the Mars novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. I

journeyed with John Carter, gentleman adventurer from Virginia, to "Barsoom,"

as Mars was known to its inhabitants. I followed herds of eight legged

beasts of burden, the thoats. I won the hand of the lovely Dejah Thoris,

Princess of Helium. I befriended a four-metre-high green fighting man named

Tars Tarkas. I wandered within the spired cities and domed pumping stations

of Barsoom, and along the verdant banks of the Nilosyrtis and Nepenthes

canals. Might it really be possible - in fact and not in fancy - to venture

with John Carter to the Kingdom of Helium on the planet Mars? Could we

venture out on a summer evening, our way illuminated by the two hurtling

moons of Barsoom, for a journey of high scientific adventure? ... I can

remember spending many an hour in my boyhood, arms resolutely outstretched

in an empty field, imploring what I believed to be Mars to transport me

there."

ON GENES, BRAINS, AND BOOKS:

"When our genes could not store

all the information necessary for survival, we slowly invented brains.

But then the time came, perhaps ten thousand years ago, when we needed

to know more than could conveniently be contained in brains. So we learned

to stockpile enormous quantities of information outside our bodies. We

are the only species on the planet, so far as we know, to have invented

a communal memory stored neither in our genes nor in our brains. The warehouse

of that memory is called the library.

A book is made from a tree. It

is an assemblage of flat, flexible parts (still called "leaves") imprinted

with dark pigmented squiggles. One glance at it and you hear the voice

of another person-perhaps someone dead for thousands of years. Across the

millennia, the author is speaking, clearly and silently, inside your head,

directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding

together people, citizens of distant epochs, who never knew one another.

Books break the shackles of time, proof that humans can work magic."

-"The Persistence

of Memory," Cosmos, p. 281.

ON THE BRAIN:

"The human brain seems to be

in a state of uneasy truce, with occasional skirmishes and rare battles.

The existence of brain components with predispositions to certain behavior

is not an invitation to fatalism or despair: we have substantial control

over the relative importance of each component. Anatomy is not destiny,

but it is not irrelevant either." -"The Future Evolution

of the Brain," The Dragons of Eden, p. 189.

ON PSEUDOSCIENCE:

"I worry that, especially as

the Millennium edges nearer, pseudoscience and superstition will seem year

by year more tempting, the siren song of unreason more sonorous and attractive.

Where have we heard it before? Whenever our ethnic or national prejudices

are aroused, in times of scarcity, during challenges to national self-esteem

or nerve, when we agonize about our diminished cosmic place and purpose,

or when fanaticism is bubbling up around us - then, habits of thought familiar

from ages past reach for the controls. The candle flame gutters. Its little

pool of light trembles. Darkness gathers. The demons begin to stir."

-"Science

and Hope," The Demon-Haunted World, pp. 26-27.

WHY PEOPLE BELIEVE NONSENSE:

"Such reports persist and proliferate

because they sell. And they sell, I think, because there are so many of

us who want so badly to be jolted out of our humdrum lives, to rekindle

that sense of wonder we remember from childhood, and also, for a few of

the stories, to be able, really and truly, to believe-in Someone older,

smarter, and wiser who is looking out for us. Faith is clearly not enough

for many people. They crave hard evidence, scientific proof. They long

for the scientific seal of approval, but are unwilling to put up with the

rigorous standards of evidence that impart credibility to that seal."

-"The Man in the Moon and the Face on Mars," The Demon-Haunted World, p.

58.

ON EXTRATERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE:

"There are some hundred billion

(1011) galaxies, each with, on the average, a hundred billion

stars. In all the galaxies, there are perhaps as many planets as stars,

1011 x 1011 = 1022, ten billion trillion. In the

face of such overpowering numbers, what is the likelihood that only one

ordinary star, the Sun, is accompanied by an inhabited planet? Why should

we, tucked away in some forgotten corner of the Cosmos, be so fortunate?

To me, it seems far more likely that the universe is brimming over with

life. But we humans do not yet know. We are just beginning our explorations.

The only planet we are sure is inhabited is a tiny speck of rock and metal,

shining feebly by reflected sunlight, and at this distance utterly lost."

-"The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean," Cosmos, p. 7.

ON DISCOVERING EXTRATERRESTRIAL

INTELLIGENCES:

"The receipt of a message from

an advanced civilization will show that there are advanced civilizations,

that there are methods of avoiding the self-destruction that seems so real

a danger of our present technological adolescence. ... Finding a solution

to a problem is helped enormously by the certain knowledge that a solution

exists. This is one of many curious connections between the existence of

intelligent life elsewhere and the existence of intelligent life on Earth."

-"Knowledge is Our Destiny," The Dragons of Eden, p. 234.

ON EXPLORING THE COSMOS:

"This is the time when humans

have begun to sail the sea of space. The modern ships that ply the Keplerian

trajectories to the planets are unmanned. They are beautifully constructed,

semi-intelligent robots exploring unknown worlds."

-"Travelers' Tales," Cosmos, p. 138.

ON THE VIEW OF EARTH FROM 3.7 BILLION

MILES AWAY AS A PALE BLUE DOT:

"Look again at that dot. That's

here. That's home, That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know,

everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their

lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions,

ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero

and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and

peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child,

inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician,

every 'superstar,' every 'supreme leader,' every saint and sinner in the

history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

... There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits

than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility

to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale

blue dot, the only home we've ever known."

-"You Are Here," Pale Blue Dot, pp. 8-9.

ON COMETS:

"Comets approach the Sun, flicker

a few hundred times, and die like moths around a flame. But a vast repository

of them waits at the periphery of the Solar System. When the present configuration

of continents is unrecognizably altered, when the Earth is engulfed by

the expanding Sun, when, in its dotage, our star feebly illuminates the

charred remains of this planet - then, even then, the skies will still

be brightened as young comets, newly arrived from the interstellar dark,

make their wild perihelion passages. When the rest of the solar system

is dead, and the descendants of humans long ago emigrated or extinct, the

comets will still be here."

-"A Mote of Dust," Comet, p. 372.

ON CHILDHOOD:

"As soon as I was old enough,

my parents gave me my first library card. I think the library was on 85th

Street, an alien land. Immediately, I asked the librarian for something

on stars. She returned with a picture book displaying portraits of men

and women with names like Clark Gable and Jean Harlow. I complained, and

for some reason then obscure to me, she smiled and found another book -

the right kind of book. I opened it breathlessly and read until I found

it. The book said something

astonishing, a very big thought.

It said that the stars were suns, only very far away. The Sun was a star,

but close up."

-"The Backbone of Night," Cosmos, p. 168.

ON CHILDHOOD DREAMS OF BEING AN

ASTRONOMER:

"When I was twelve, my grandfather

asked me-through a translator (he had never learned much English)-what

I wanted to be when I grew up. I answered, 'An astronomer,' which, after

a while, was also translated. 'Yes,' he replied, 'but how will you make

a living?' I had supposed that, like all the adult men I knew, I would

be consigned to a dull, repetitive, and uncreative job; astronomy would

be done on weekends. It was not until my second year in high school that

I discovered that some astronomers were paid to pursue their passion. I

was overwhelmed with joy; I could pursue my interest full-time."

-"Preface," The Cosmic Connection, p. vii.

ON GOD:

"Because the word 'God' means

many things to many people, I frequently reply [to people who ask 'Do you

believe in God?'] by asking what the questioner means by 'God.' To my surprise,

this response is often considered puzzling or unexpected: 'Oh, you know,

God. Everyone knows who God is.' Or 'Well, kind of a force that is stronger

than we are and that exists everywhere in the universe.' There are a number

of such forces. One of them is called gravity, but it is not often identified

with God. And not everyone does know what is meant by 'God.'...Whether

we believe in God depends very much on what we mean by God.

My deeply held belief is that

if a god of anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and

intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of

those gifts (as well as unable to take such a course of action) if we suppressed

our passion to explore the universe and ourselves. On the other hand, if

such a traditional god does not exist, our curiosity and our intelligence

are the essential tools for managing our survival. In either case, the

enterprise of knowledge is consistent with both science and religion, and

is essential for the welfare of the human species."

-"A Sunday Sermon," Broca's Brain, p. 291.

ON THEISM AND ATHEISM:

"Those who raise questions about

the God hypothesis and the soul hypothesis are by no means all atheists.

An atheist is someone who is certain that God does not exist, someone who

has compelling evidence against the existence of God. I know of no such

compelling evidence. Because God can be relegated to remote times and places

and to ultimate causes, we would have to know a great deal more about the

universe than we do now to be sure that no such God exists. To be certain

of the existence of God and to be certain of the nonexistence of God seem

to me to be the confident extremes in a subject so riddled with doubt and

uncertainty as to inspire very little confidence indeed. A wide range of

intermediate positions seems admissible, and considering the enormous emotional

energies with which the subject is invested, a questioning, courageous

and open mind seems to be the essential tool for narrowing the range of

our collective ignorance on the subject of the existence of God."

-"The Amniotic Universe," Broca's Brain, p. 311.

ON A PLEA FOR TOLERANCE:

"We have held the peculiar notion

that a person or society that is a little different from us, whoever we

are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or loathed. Think

of the negative connotations of words like alien or outlandish. And yet

the monuments and cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent

different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial visitor, looking at

the differences among human beings and their societies, would find those

differences trivial compared to the similarities. The Cosmos may be densely

populated with intelligent beings. But the Darwinian lesson is clear: There

will be no humans elsewhere. Only here. Only on this small planet. We are

a rare as well as an endangered species. Every one of us is, in the cosmic

perspective, precious. If a human disagrees with you, let him live. In

a hundred billion galaxies, you will not find another."

-"Who Speaks for Earth?," Cosmos, p. 339.

ON SCIENCE LITERACY:

"All inquiries carry with them

some element of risk. There is no guarantee that the universe will conform

to our predispositions. But I do not see how we can deal with the universe-both

the outside and the inside universe-without studying it. The best way to

avoid abuses is for the populace in general to be scientifically literate,

to understand the implications of such investigations. In exchange for

freedom of inquiry, scientists are obliged to explain their work. If science

is considered a closed priesthood, too difficult and arcane for the average

person to understand, the dangers of abuse are greater. But if science

is a topic of general interest and concern - if both its delights and its

social consequences are discussed regularly and competently in the schools,

the press, and at the dinner table - we have greatly improved our prospects

for learning how the world really is and for improving both it and us."

-"Broca's Brain," Broca's Brain, p. 12.

ON SCIENCE AND UNCERTAINTY:

"We will always be mired in error.

The most each generation can hope for is to reduce the error bars a little,

and to add to the body of data to which error bars apply. The error bar

is a pervasive, visible self-assessment of the reliability of our knowledge.

You can often see error bars in public opinion polls...Imagine a society

in which every speech in the Congressional Record, every television commercial,

every sermon had an accompanying error bar or its equivalent."

-"Science and Hope," The Demon-Haunted World, p. 28.

ON HUMANS AND ANIMALS:

"We must stop pretending we're

something we are not. Somewhere between romantic, uncritical anthropomorphizing

of the animals and an anxious, obdurate refusal to recognize our kinship

with them - the latter made tellingly clear in the still-widespread notion

of 'special' creation - there is a broad middle ground on which we humans

can take our stand."

-"Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors," Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, p. 413.

ON VELIKOVSKY:

"In the entire Velikovsky affair,

the only aspect worse than the shoddy, ignorant and doctrinaire approach

of Velikovsky and many of his supporters was the disgraceful attempt by

some who called themselves scientists to suppress his writings. For this,

the entire scientific enterprise has suffered. Velikovsky makes no serious

claim of objectivity or falsifiability. There is at least nothing hypocritical

in his rigid rejection of the immense body of data that contradicts his

arguments. But scientists are supposed to know better, to realize that

ideas will be judged on their merits if we permit free inquiry and vigorous

debate."

-"Venus and Dr. Velikovsky," Broca's Brain, p. 127

BIOLOGY AND HISTORY:

"Biology is much more like language

and history than it is like physics and chemistry. ...Now you might say

that where the subject is simple, as in physics, we can figure out the

underlying laws and apply them everywhere in the Universe; but where the

subject is difficult, as in language, history, and biology, governing laws

of Nature may well exist, but our intelligence may be too feeble to recognize

their presence - especially if what is being studied is complex and chaotic,

exquisitely sensitive to remote and inaccessible initial conditions. And

so we invent formulations about "contingent reality" to disguise our ignorance.

There may well be some truth to this point of view, but it is nothing like

the whole truth, because history and biology remember in a way that physics

does not. Humans share a culture, recall and act on what they've been taught.

Life reproduced the adaptations of previous generations, and retains functioning

DNA sequences that reach billions of years back into the past. We understand

enough about biology and history to recognize a powerful stochastic component,

the accidents preserved by high-fidelity reproduction."

-"Life is Just a Three-Letter Word," Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, p.

92.

ON THE TRANSIENCE OF LIFE:

"Each of us is a tiny being,

permitted to ride on the outermost skin of one of the smaller planets for

a few dozen trips around the local star. ...The longest-lived organisms

on Earth endure for about a millionth of the age of our planet. A bacterium

lives for one hundred-trillionth of that time. So of course the individual

organisms see nothing of the overall pattern-continents, climate, evolution.

They barely set foot on the world stage and are promptly snuffed out --

yesterday a drop of semen, as the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote,

tomorrow a handful of ashes. If the Earth were as old as a person, a typical

organism would be born, live, and die in a sliver of a second. We are fleeting,

transitional creatures, snowflakes fallen on the hearth fire. That we understand

even a little of our origins is one of the great triumphs of human insight

and courage."

-"Snowflakes Fallen on the Hearth," Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, pp.

30-31.

ON LIFE AND DEATH:

"Most people would rather be

alive than dead. But why? It's hard to give a coherent answer. An enigmatic

"will to live" or "life force" is often cited. But what does that explain?

Even victims of atrocious brutality and intractable pain may retain a longing,

sometimes even a zest, for life. Why, in the cosmic scheme of things, one

individual should be alive and not another is a difficult question, an

impossible question, perhaps even a meaningless question. Life is a gift

that, of the immense number of possible but unrealized beings, only the

tiniest fraction are privileged to experience. Except in the most hopeless

of circumstances, hardly anyone is willing to give it up voluntarily -

at least until very old age is reached."

-"What Thin Partitions...," Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, p. 159.

"If we're absolutely sure that our

beliefs are right, and those of others wrong; that we are motivated by

good, and others by evil; that the King of the Universe speaks to us, and

not to adherents of very different faiths; that it is wicked to challenge

conventional doctrines or to ask searching questions; that our main job

is to believe and obey - then the witch mania will recur in its infinite

variations down to the time of the last man."

"Our loyalties are to the species

and the planet. We speak for Earth. Our obligation to survive is owed not

just to ourselves but to that Cosmos, ancient and vast, from which we spring."

"There is a place with four suns in the

sky-red, white, blue, and yellow; two of them are so close together that

they touch, and star-stuff flows between them. I know of a world with a

million moons. I know of a sun the size of the Earth-and made of diamond....

The universe is vast and awesome, and for the first time we are becoming

part of it."

-Carl Sagan,

The Cosmic Connection

"How

is it that hardly any major religion has looked at science and concluded,

'This is better than we thought! The Universe is much bigger than our prophets

said, grander, more subtle, more elegant'? Instead they say, 'No, no, no!

My god is a little god, and I want him to stay that way.' A

religion old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the universe as

revealed

by modern science, might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and

awe hardly tapped by the conventional faiths. Sooner or later, such a religion

will emerge."

-

Carl

Sagan, Pale Blue Dot (1994)

"It

is said that men may not be the dreams of the Gods, but rather that the

Gods are the dreams of men."

"I believe that the extraordinary should

be pursued. But extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence."

"Our loyalties are to the species and the

planet. We speak for Earth. Our obligation to survive is owed not just

to ourselves but also to that Cosmos, ancient and vast, from which we spring."

- Cosmos

"Absence of evidence is not

evidence of absence"

"When Kepler found his long-cherished

belief did not agree with the most precise observation, he accepted the

uncomfortable fact. He preferred the hard truth to his dearest illusions,

that is the heart of science." - Cosmos

"History is full of people who

out of fear, or ignorance, or lust for power have destroyed knowledge of

immeasurable value which truly belongs to us all. We must not let it happen

again."

- Cosmos

"We are the product of 4.5 billion

years of fortuitous, slow biological evolution. There is no reason to think

that the evolutionary process has stopped. Man is a transitional animal.

He is not the climax of creation."

- The Cosmic

Connection

"The surface of the Earth is the

shore of the cosmic ocean. From it we have learned most of what we know.

Recently, we have waded a little out to sea, enough to dampen our toes

or, at most, wet our ankles. The water seems inviting. The ocean calls.

Some part of our being knows this is from where we came. We long to return.

These aspirations are not, I think, irreverent, although they may trouble

whatever gods may be." - Cosmos

"It has been said that astronomy

is a humbling and character building experience. There is perhaps no better

demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of

our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly

with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only

home we've ever known."

- Pale Blue

Dot

"The wind whips through the canyons

of the American Southwest, and there is no one to hear it but us -- a reminder

of the 40,000 generations of thinking men and women who preceded us, about

whom we know almost nothing, upon whom our civilization is based." -

Cosmos

"You have to know the past to

understand the present." - Cosmos

"We are like the inhabitants

of an isolated valley in New Guinea who communicate with societies in neighboring

valleys (quite different societies, I might add) by runner and by drum.

When asked how a very advanced society will communicate, they might guess

by an extremely rapid runner or by an improbably large drum. They might

not guess a technology beyond their ken. And yet, all the while, a vast

international cable and radio traffic passes over them, around them, and

through them...

"We will listen for the interstellar

drums, but we will miss the interstellar cables. We are likely to receive

our first messages from the drummers of the neighboring galactic valleys--from

civilizations only somewhat in our future. The civilizations vastly more

advanced than we, will be, for a long time, remote both in distance and

in accessibility. At a future time of vigorous interstellar radio traffic,

the very advanced civilizations may be, for us, still insubstantial legends."

- The Cosmic

Connection

"But for us, it's different. Look

again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone

you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being

who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering,

thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every

hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer

of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every

mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher

of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme

leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there

- on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

"The Earth is a very small stage

in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those

generals and emperors, so that, in glory and triumph, they could become

the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties

visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely

distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings,

how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

"Our posturings, our imagined

self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in

the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is

a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in

all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere

to save us from ourselves."

- Pale Blue

Dot

I

would love to believe that when I die I will live again, that some thinking,

feeling, remembering part of me will continue. But much as I want to believe

that, and despite the ancient and worldwide cultural traditions that assert

an afterlife, I know of nothing to suggest that it is more than wishful

thinking.

The world is so exquisite with

so much love and moral depth, that there is no reason to deceive

ourselves with pretty stories for which there's little good evidence. Far

better it seems to me, in our vulnerability, is to look death in the eye

and to be grateful every day for the brief but magnificent opportunity

that life provides.

In science it often happens that scientists

say, "You know that's a really good argument; my position is mistaken,"

and then they would actually change their minds and you never hear that

old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often

as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful.

But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like

that happened in politics or religion.

-- Carl Sagan ~“The Burden

of Skepticism,” Lecture 1987

"I don't want to believe, I want to know".

Carl Sagan

"Was Carl Sagan a religious man?

He was so much more. He left behind the petty, parochial, medieval world

of the conventionally religious; left the theologians, priests and mullahs

wallowing in their small-minded spiritual poverty. He left them behind,

because he had so much more to be religious about. They have their Bronze

Age myths, medieval superstitions and childish wishful thinking. He had

the universe."~

Richard Dawkins

"How was it, Carl wondered, that the

eternal and omniscient Creator described in the Bible could confidently

assert so many fundamental misconceptions about Creation? Why would the

God of the Scriptures be far less knowledgeable about nature than are we,

newcomers, who have only just begun to study the universe? He could not

bring himself to overlook the Bible's formulation of a flat, six-thousand-year-old

earth, and he found especially tragic the notion that we had been created

separately from all other living things. The discovery of our relatedness

to all life was borne out by countless distinct and compelling lines of

evidence. For Carl, Darwin's insight that life evolved over the eons through

natural selection was not just better science than Genesis, it also afforded

a deeper, more satisfying spiritual experience."

~ Ann Dru