HOUGH, EMERSON, 1857-1923

Journalist, editor of Forest and Stream, and novelist of the West.

Emerson Hough's American

West by Carole M. Johnson: From Books at Iowa 21 (November 1974) Copyright:

The University of Iowa

http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/Bai/johnson.htm

As a working journalist,

Hough traveled over the American West in the closing decades of the nineteenth

century when the West was being ransformed from a wilderness into a civilized

region. He participated in that change inasmuch as his writing contributed

to the integration of the West into the national identity. Like his friend

Theodore Roosevelt, Hough developed into an historian of the westward expansion

and an ardent patriot who saw in the western experience the traditional

American ideals of individuality, courage, strength, and pragmatic integrity

he felt were necessary for the survival of modern America. As a writer

of western history and fiction, Hougli sought to establish the West as

a subject with enough dignity and interest to transcend the popular image

of the Wild West cultivated by writers ignorant of the true West or its

past. As a conservationist and an authoritative commentator on every sport

from fly casting to bear hunting, he sought to preserve the American wilderness

because he saw it as a source of the nation's strength and uniqueness.

His most popular novels,

The Covered Wagon (1922) and North

of 36 (1923), were the culmination of his efforts to identify the West

with the ideals of the American past.

Though a midwesterner, Hough

was a product of the frontier tradition. He was born in Newton, Iowa, on

June 28, 1857. His parents, Joseph Bond Hough and Elizabeth Hough, had

emigrated from Virginia to Jasper County, Iowa, in 1852.John, the first

Hough to reach the American colonies, had emigrated from Chester, England,

in 1683, and his descendants subsequently moved from Pennsylvania to Loudoun

County, Virginia. Emerson Hough was always proud of his southern, Anglo-Saxon

ancestry because it testified to his "ancient, undeniable one hundred percent

Americanism." Joseph Hough taught school, served as a county clerk, worked

as a county surveyor and a farmer, and at one time was a grain and lumber

merchant. Emerson Hough himself displayed the same kind of frontier versatility

in his lifetime. In fact, his father was the prototype for many of his

fictional heroes and a pattern for his own life. "My father was a Virginian,"

Hough said once, "a grand man as I look at it, simple, temperate, manly,

the best shot with rifle or gun that I ever saw. I suppose I got my love

of field sports and my love of the Old West from him -- that it was heredity

that sent me west and shaped much of my later course of life." Hough was

a proficient sportsman himself, hunting and fishing in every state of the

Union and in Canada and Mexico before he died. He maintained a husky appearance

and led a strenuous life in spite of constant illnesses which plagued him

from childhood. Fortunately, this enforced idleness as a child allowed

him to read a great deal. He indulged his preference for romanticism in

Tennyson's Idylls of the King; and the battle scenes in the Biblical Book

of Kings provided a natural transition to Ivanhoe and most of Walter Scott's

historical fiction. Perhaps the book which influenced Hough most was Henry

Howe's Historical Collections of the Great West, published in Cincinnati

in 1851. "I still think this is one of the great books of America," he

said, for it showed us America as it once was -- the most wonderful country

ever occupied by civilization. I wish those old days were back, or that

I had been born in them." As a youth, Hough was deeply impressed

by Howe's declaration in the preface of his book that historical fiction

had greater charm than plain history.

Hough graduated with two

other pupils from the local high school at Newton, Iowa, in 1875, and after

teaching in a country school for one term, he entered The University of

Iowa in 1876. His university career was an eventful one in which he played

on the football team, edited the college newspaper, and graduated

Phi Beta Kappa in 1880. Hough's father urged his son to study law, partly

out of his own failure in that ambition for himself; but reluctant to enter

the legal profession, Hough spent some time as a surveyor in a civil engineering

party before deciding to read law. As a diversion from his studies he began

to write sketches on the outdoors and on hunting for publication in eastern

magazines. His first published article, "Far From the Madding Crowd," which

appeared in Forest and Stream (August 17, 1882), revealed a romantic primitivism

which was to pervade his later work: "There is no more natural or effective

way to rest," he wrote, "than to merge for a time the artificial man into

the natural; to sink civilized training in the instincts given us by our

fathers, the savages . . ."

Hough was admitted to the

bar in 1882 at Newton, Iowa. Shortly thereafter, an unhappy love affair

precipitated a desire to travel west. Fortunately a friend who was practicing

law in White Oaks, New Mexico, invited him to join his law firm there,

and when the American Field offered him a free railroad pass to write some

sketches on the Southwest for them, Hough left immediately for New Mexico.

The New Mexico Territory

in the 1880's was a place of social and political upheaval, the scene of

murders, range wars, Indian uprisings, and the coming of the railroad-the

last frontier. Hough arrived in White Oaks on June 1, 1883, and formed

a law partnership with Eli H. Chandler. At this time White Oaks -- "half

mining camp and half cow camp" -- was considerably tamer than its neighbors,

Lincoln and Fort Stanton, which were just recovering from the ravages of

the Lincoln County War and the tempestuous career of the late outlaw, Billy

the Kid. But, despite the inevitably numerous legal proceedings typical

of a mining community, Hough and his partner did not have much of a law

practices Increasingly, Hough was more attracted to the pleasures of the

hunt than to the drudgeries of the law, and he later admitted that he devoted

a great deal of time to bear hunting. Recognizing that a man had to be

versatile in order to survive, Hough spent the remainder of his time working

as a reporter and sometime editor on the Golden Era, a weekly White Oaks

newspaper. Eventually, journalism began to occupy as much of his time as

hunting.

During his stay in New Mexico,

Hough bad been gathering material for the American Field and other Midwestern

publications like Field and Stream and Outing. In a series of sketches

which appeared in the American Field from June 2, 1883, to May 31, 1884,

he wrote about his travels in the Southwest. These sketches reveal a perceptive

response to an environment that must have appeared strange if not extraordinary

to the young man from the Midwest. This response often takes a humorous

and, in some cases, comic form, foreshadowing some of his best work in

Heart's Desire. Other more serious sketches show a remarkable insight into

the powerful influence of the frontier environment upon its inhabitants,

at its worst twisting the soul with loneliness, at its best eliciting superior

qualities of courage, self-reliance, individuality, and pragmatic integrity

that were necessary for survival in the West. "The ancient law of individualism

and of the survival of those who ought to survive, was the actual law of

the land," Hough wrote of the West be had known in the 1880's, and he firmly

believed and advocated the idea that "environment produced the creature."

To a great extent Hough's life in White Oaks determined the kind of values

he admired, but his attachment to White Oaks was based on more than a youthful

romanticism. While he was frankly idealistic about the place, he also recognized

that White Oaks, as he had known it, had been real, and he was concerned

with capturing that reality before it vanished into unrecognizable myth:

"One saw there the actual old West, not the railroad tourist West, but

the real West, with its population made up of flotsam and jetsam of the

westbound tide of humanity." Consequently, in his best western fiction,

Hough based his stories on his own personal observations and experiences,

showing little tendency to romanticize or exaggerate his characters or

the West.

In February, 1884, Hough

returned to Iowa to attend his mother, who was ill. When he found his father

in serious financial difficulties, he abandoned the law altogether and

turned to journalism to support his family. From February to October of

1884, he worked as the business manager of the Des Moines Times,

and in late November of that year he became the associate editor of the

Register in Sandusky, Ohio. Hough also wrote humorous stories for the McClure-Phillips

syndicate at five dollars a column and articles on sports for the St. Louis

Globe-Democrat at six dollars a column. From Sandusky, Ohio, he went in

1889 to Chicago, where be worked on the American Field, the sporting publication

to which be had previously contributed. His assignments for this magazine

took him to Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, the Indian

Nations, Texas, and other wild, remote parts of the country. He later recalled

that by age thirty-two he had been successively "a sewer of grain sacks,

a rodman, a levelman, a law student, a lawyer, an editor, a reporter, a

solicitor, a collector of bad debts, a special writer, a townsite boomer,

and a newspaper owner." Since 1882 he had contributed occasional

sketches on hunting and fishing to Forest and Stream, a New York sporting

journal, and in 1889 he became its western representative. His responsibility

was to edit the "Chicago and the West" column for fifteen dollars a week.

His job also required him to solicit advertising, an activity he disliked

intensely. Nevertheless he resolved to become "the best posted man in America

engaged in the journalism of outdoor sports." Of the years between

1889 and 1904 he later wrote: "I never worked harder in my life than I

did at this time, and I don't know that I have ever been happier. In all

this time I was getting a sort of education which embraced pretty much

all of western America. I knew western standards and western life pretty

well."

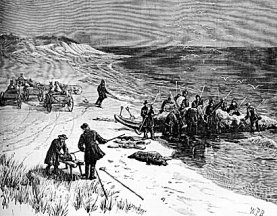

One of Hough's trips during

this period had far-reaching effects. In the winter of 1893, in company

with his friend and guide Billy Hofer and two soldiers from Fort Yellowstone,

Hough crossed the whole of Yellowstone National Park in below-zero temperatures

for the purpose of photographing the wild game and counting the buffalo,

whose number was dwindling because of the encroachment of winter poachers.

Though the authorities thought there were five hundred buffalo left in

the park, Hough could hardly find one hundred. In the course of his trip

be was also instrumental in capturing a poacher. When the army fined the

poacher only by confiscating his outfit, Hough was outraged and wrote a

report showing the absurdity of the park regulations as practical protection

for the wildlife and emphasizing also the actual extent of the ravages

of the poachers on the park buffalo. This report, later published in an

eastern newspaper, moved Congress in May, 1894, to pass a strong law making

the poaching of wild game in the park a punishable offense, the first time

that government protection had ever been given to the buffalo. Hough said

of his part in this historic event: "I have always thought this was about

as useful a thing as I ever was able to do in the somewhat thankless attempt

to be of service to the wildlife of America."

By 1897 Hough had reached

middle age without notable professional success. Marriage to Charlotte

Cheesebro in that year brought stability into his life and gave a direction

to his career. In order to increase his income he began utilizing the accumulated

experience of years of travel and bservation-what he called his "vacation

work"- by writing about what he knew best. In 1896, through the influence

of George Bird Grinnell, owner of Forest and Stream, Hough was asked to

do a volume on the cowboy for the "History of the West" series, edited

by Ripley Hitchcock. The Story of the Cowboy (1897), a historical and factual

treatment of the cowboy and his life which is still considered a classic

document on the cattle industry, established Hough's reputation as a western

writer. Critical reception of the book was almost unanimously favorable

and even enthusiastic, and the praise of people like Hamlin Garland and

Theodore Roosevelt encouraged Hough tremendously. Garland wrote to Hough,

saying that "It is a splendid performance. It has the power of the larger

sort. It has dignity, restraint and structure. I wish I had written it

myself." Theodore Roosevelt's approval meant even more to Hough; he marked

this year as his true arrival as a western writer and Roosevelt's congratulatory

letter as a landmark and inspiration in his life:

Though The Story of the Cowboy

did not make much money, Hough was encouraged to complete his next book

(a novel this time) within a few months, working on it at night and pursuing

his journalistic activities during the day. When it was published in 1900,

The Girl at the Halfway House attracted little attention and made even

less money. Though not an artistically successful novel, The Girl dealtthoughtfully

and intelligently with the problems of the settlement of the West, focusing

specifically on the development of a Kansas cow town into a prosperous,

civilized city. In fact, this novel and the short stories Hough wrote during

this period show an artistic and intellectual growth, and their success

is based mainly on his objectivity and bonesty in dealing with western

themes.

Not until the publication

of The Covered Wagon in 1922 did Hough enjoy again the success of his first

bestseller, The Mississippi Bubble. Nevertheless in the intervening years

his writing afforded him a comfortable living. He enjoyed his career despite

the constant pressure to produce a steady stream of marketable material,

most of which he gathered on his summer trips. Hough responded to these

demands with incredible stamina and ingenuity, in some cases using the

same material in different ways. For example, a financially disastrous

investment in farming by irrigation in Texas became the basis for an amusing

and informative article, "Under the Ditch in Texas," which appeared in

Outing (February, 1909). In another instance, Hough satirized the land

frauds he had discovered taking place in the West through a series of Curly

stories which appeared from 1909-1913 in the Post, Collier's, and the Popular

Monthly. Unable to editorialize on these land abuses for fear of offending

the editors of the Post, who were closely allied with big business, Hough

wrote these stories out of a sense of indignation, and incidentally produced

some of his better fiction.

Hough's inability to make

money on his western fiction continued to discourage him considerably,

and after 1913 be produced a large number of articles, short stories, and

books on more topical, modern concerns. Most of his important work was

done in conservation. These articles were often reprinted by conservation

clubs and did much to promote the movement nationwide. Hough also wrote

"The Young Alaskans" series of books for young people, encouraging them

to enjoy outdoor life and preserve the natural environment. In fact, Hough

was so active in the conservation of the national parks that on different

occasions he was offered the position of superintendent of Yellowstone

Park and Grand Canyon Park. He turned down the offers because the salary

was too low, but he admitted privately that an official position, especially

a government post, would restrict his freedom. Nevertheless, he did

not lose his passion for western history, and in 1917 he eagerly accepted

an invitation to write a volume on western subjects for the "Chronicles

of America" series, a cooperative history in fifty volumes, edited by Allen

Johnson for the Yale University Press. The general editorial scheme was

to relate American history in terms of "a romantic adventure of epic proportions."

Hough's contribution, The Passing of the Frontier: A Chronicle of the Old

West (1918), fit this requirement exactly because it was a compilation

of his sketches and articles from previous years. He did not attempt to

discuss the influence of the frontier on American politics as be had done

in his earlier historical accounts. Instead, he included chapters on the

more striking phases of frontier life in the Far West in its mid-century

stage of existence. In an about-face from his previous views in The Story

of the Cowboy and The Story of the Outlaw, in which he had glorified the

individual hero, he reserved his highest praise in The Passing of the Frontier

for the settlers:

The chief figure of the American

West, figure of the ages, is not the longbaired, fringed-legging man riding

a raw-boned pony, but the gaunt and sad-faced woman, following her lord

where he might lead, her face bidden in the same ragged sunbonnet which

bad crossed the Appalachians and the Missouri long before. That was America,

my brethren! There was the seed of America's wealth. There was the great

romance of all America-the woman in the sunbonnet; and not, after all,

the hero with the rifle across his saddle horn.

The research be had done

for The Passing of the Frontier became the basis for a series of articles

on western themes that Hough wrote for the Post in 1919, "Traveling the

Old Trails." A few of the subjects Hough dealt with were the pioneer migration

of the 1840's, the early exploration of the Far West and the Northwest

by Lewis and Clark, and the cattle industry, the subjects of his earlier

and more successful work. These articles were marked by an extreme patriotism

and individualism, a personal reaction to what he considered the socialist

threat to the American political system. Indeed, this resurgence of interest

in the national heritage of older, simpler values was symptomatic of his

general bewilderment at the social upheavals, the complex international

politics, and the changing social mores of the postnvar period. In a series

of letters he wrote to his friend Frederick Bigelow, Hough expressed these

feelings. In 1921 he wrote: "I'm afraid I belong to an earlier age ...

when I see the jazz life of these hysterical tourists bent on pleasure

and burry, I like that not even so well. I reckon there is no place for

me." [29] In a letter which revealed the source of his nostalgia, Hough

wrote of his disgust with the current administration, the govemment, and

the country in general, and he added wistfully: "If I knew of any place

in the world like White Oaks, New Mexico, as it was in 1880 I should take

the next train thither." [30]

The Covered Wagon (1922)

was written in this mood, and it was an immediate and spectacular success.

Most reviewers praised the book, not for its literary merit, which they

readily acknowledged as negligible, but for its description of an event

of great interest and importance, the pioneer migration of the 1840's.

The appeal of the novel lay in Hough's graphic visualization of the pioneer

advance in the West and the purpose and courage of the dauntless pioneers,

suffering, great danger and privation to achieve their goal. This representation

of the past was met with great approval by the public because it affirmed

the sanctity of older values and offered hope that these values would prevail

again. The nostalgic awareness of The West That Was, which dominated The

Passing of the Frontier, was present in The Covered Wagon and to a certain

extent determined its success. Similarly, when the motion picture based

on Hough's book was made, its patriotic appeal was probably as much responsible

for its huge commercial success as its spectacular elements. It ran fifty-nine

weeks at the Criterion Theater in New York City, eclipsing the record of

The Birth of a Nation. The film's "thrilling

interpretation of the pioneer

spirit that made America" impressed one reviewer particularly. His observation

that "boys and girls will get from its two hours a vivid and lasting impression

of the history of their country that would generally be too much to hope

for from months of conventional study" is evidence that Hough's desire

to teach Americans a proper version of their own history was fulfilled.

[31] In much the same vein Robert E. Sherwood gave Hough this tribute-.

"He had the ultimate satisfaction of knowing that he had honestly reflected

a period in American history of which every American has a right to be

proud." [32]

What The Covered Wagon had

done for the romantic pioneer days of the 1840's, North of 36 (1923) did

on the same sweeping scale for the cattle trail days of the 1870's. Hough

began working on the new novel even before the publication of the Wagon.

Although persistent illness plagued him, he characteristically refused

to slow down. While vacationing in Colorado in early July, 1922, he became

gravely ill and had to be hospitalized. Thinking he would not live long

enough to finish his novel, Hough called his friend Andy Adams, explained

to him his outline for the book, and asked him to finish it. Nevertheless,

Hough recovered enough to return to Chicago by December, 1922, with an

almost completed manuscript. He sold the serial rights to the Post for

fifteen thousand dollars, and in February, 1923, he sold the picture rights

for the spectacular sum of thirty thousand dollars. [33] Hough was never

able to enjoy this success. Having achieved at last the financial security

he had worked so long and hard to get, he died on April 30, 1923, just

a week after he had attended the Chicago premier of The Covered Wagon.

It is fitting that North

of 36 was his last novel. [34] Concerned with the beginning of the great

cattle drives from Texas northward in the Reconstruction days, the whole

novel focuses on the cattle trail, which Hough saw uniting North and South

and creating the "first and only true American tradition -- the tradition

of the West." [35] Though North of 36 had little literary merit, Hough

had created a regional novel that was for the most part faithful to the

customs and practices of the Texas cattle country. He had realized the

main objective of his career in western writing -- to identify the tradition

of the West with the American tradition.

The Covered Wagon and North

of 36 were the culmination of Hough's lifelong ambition to integrate the

West into the national identity. Though his historical fiction was often

marred by a tendency toward didacticism and an adherence to a rigid romantic

formula, he reaffirmed the values of a past that were threatened at a time

of social and political upheaval. Moreover, in all phases of his writing

he bequeathed a vision of America defined in terms of the western experience,

and he made this vision a part of the national heritage. |

Joseph

Hergesheimer (1880-1954): author of The Lay Anthony, Mountain

Blood, The Three Black Pennys, Java Head, Linda Condon, Cytherea, The Bright

Shawl, Wild Oranges, The Dark Fleece, The Happy End, San Cristobal De La

Habana (Cuba), etc.

Joseph

Hergesheimer (1880-1954): author of The Lay Anthony, Mountain

Blood, The Three Black Pennys, Java Head, Linda Condon, Cytherea, The Bright

Shawl, Wild Oranges, The Dark Fleece, The Happy End, San Cristobal De La

Habana (Cuba), etc.

Grace

Livingston Hill: A Life Lived for Christ ~ She was born in Wellsville,

New York to a young Presbyterian minister and a published writer. It is

no wonder that Grace received such strong talents and strength in God from

her parents for they were the role models, along with her Savior Jesus

Christ, that shaped each and every decision in her life. Grace once said

that her father was the man to which she compared all other men. She was

very close to both her mother and father, but was also very close to her

Aunt Isabella, also a published writer more commonly known as Pansy. Along

with her mother, Pansy spawned the interest in writing and telling stories

at a very young age. On Grace's twelfth birthday, Pansy gave her a very

special gift. From one of the stories that Grace had recited to her, Pansy

took the initiative to type out the manuscript and send the story to her

publisher. Pansy presented Grace with a little hardback book. Her first

book had been printed by D. Lothrop Company, which was also one of Grace's

publishers later in life. During most of Grace's teenage years, she remained

close to her parents. Her father, being a minister, was called to different

areas of the eastern United States, and she would always help out with

her father and his congregation. Her father was called to Florida and while

they were there, Grace obtained a job at a local school as a gymnastics

instructor. It was not until Grace wanted to take a trip to Chautauqua

Lake in New York where her family had gathered together in the summer for

years. She desired to go so badly, but her family was not financially stable

enough at that time to take such an extravagant trip. Once Grace became

determined to go to Chautauqua, she became determined raise the funds to

make the trip possible. This was when Grace began writing her first book,

The Chautauqua Idyle, which was published by D. Lothrop Company and was

distributed at the conference in Chautauqua. Grace was also in attendance

at the conference, and she had achieved her goal. She now knew that she

was capable of something great. This was just the beginning of her long

and fulfilling writing career. She had began courting a couple of

men, but it was Fred Hill, a young minister much like her father, which

took Grace's heart. They married and had two daughters all while she continued

her writing career. She taught her daughters at home, and she always had

time for raising them in accordance with the Word of God. It wasn't until

her husband died that things changed for the worse. Grace was forced to

go out on her own and make a living for herself. It was at this time that

her writing became more than just a passion and hobby but a career for

financial purposes. Just when she thought that things could not get worse,

her father died as well. Grace's mother came to live with her, and was

very helpful in raising Grace's two daughters. Grace soon became strengthened

her God and with His Blessings, was able to go on with her life.

Grace later married Flavius Josephus Lutz who was the organist at her local

church. Grace thought that she might have a chance at normalcy for awhile,

but second marriage soon began to tragically dissolve. It took ten difficult

years before Grace finally asked the verbally abusive Flavius to leave.

Grace never divorced Flavius, but she did stop using his surname. After

the separation, much of the excitement in Grace's life began to settle.

Grace continued to write and remained a large part of her daughter's lives

and later also in her daughter's husband's lives. Grace would later say

that she was too much a part of their lives, but everything fell comfortably

into place. Grace went on to write over

Grace

Livingston Hill: A Life Lived for Christ ~ She was born in Wellsville,

New York to a young Presbyterian minister and a published writer. It is

no wonder that Grace received such strong talents and strength in God from

her parents for they were the role models, along with her Savior Jesus

Christ, that shaped each and every decision in her life. Grace once said

that her father was the man to which she compared all other men. She was

very close to both her mother and father, but was also very close to her

Aunt Isabella, also a published writer more commonly known as Pansy. Along

with her mother, Pansy spawned the interest in writing and telling stories

at a very young age. On Grace's twelfth birthday, Pansy gave her a very

special gift. From one of the stories that Grace had recited to her, Pansy

took the initiative to type out the manuscript and send the story to her

publisher. Pansy presented Grace with a little hardback book. Her first

book had been printed by D. Lothrop Company, which was also one of Grace's

publishers later in life. During most of Grace's teenage years, she remained

close to her parents. Her father, being a minister, was called to different

areas of the eastern United States, and she would always help out with

her father and his congregation. Her father was called to Florida and while

they were there, Grace obtained a job at a local school as a gymnastics

instructor. It was not until Grace wanted to take a trip to Chautauqua

Lake in New York where her family had gathered together in the summer for

years. She desired to go so badly, but her family was not financially stable

enough at that time to take such an extravagant trip. Once Grace became

determined to go to Chautauqua, she became determined raise the funds to

make the trip possible. This was when Grace began writing her first book,

The Chautauqua Idyle, which was published by D. Lothrop Company and was

distributed at the conference in Chautauqua. Grace was also in attendance

at the conference, and she had achieved her goal. She now knew that she

was capable of something great. This was just the beginning of her long

and fulfilling writing career. She had began courting a couple of

men, but it was Fred Hill, a young minister much like her father, which

took Grace's heart. They married and had two daughters all while she continued

her writing career. She taught her daughters at home, and she always had

time for raising them in accordance with the Word of God. It wasn't until

her husband died that things changed for the worse. Grace was forced to

go out on her own and make a living for herself. It was at this time that

her writing became more than just a passion and hobby but a career for

financial purposes. Just when she thought that things could not get worse,

her father died as well. Grace's mother came to live with her, and was

very helpful in raising Grace's two daughters. Grace soon became strengthened

her God and with His Blessings, was able to go on with her life.

Grace later married Flavius Josephus Lutz who was the organist at her local

church. Grace thought that she might have a chance at normalcy for awhile,

but second marriage soon began to tragically dissolve. It took ten difficult

years before Grace finally asked the verbally abusive Flavius to leave.

Grace never divorced Flavius, but she did stop using his surname. After

the separation, much of the excitement in Grace's life began to settle.

Grace continued to write and remained a large part of her daughter's lives

and later also in her daughter's husband's lives. Grace would later say

that she was too much a part of their lives, but everything fell comfortably

into place. Grace went on to write over