-384-

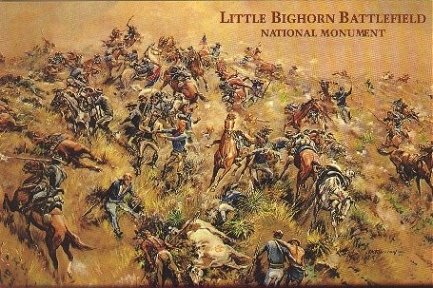

not drive the whole valley full of warriors, and in much perturbation

and worry he sounded the halt, rally, and mount. Then for a few moments,

that to his officers and men must have seemed hours, he paused irresolute,

not knowing what to do.

The Indians settled it for him. They well interpreted his hesitation.

"The White Chief was scared"; and now was their chance. Man and boy they

came tearing to the spot. A few well- aimed shots knocked a luckless trooper

or two out of the saddle. Reno hurriedly ordered a movement by the flank

toward the high bluffs across the stream to his right rear. He never thought

to dismount a few cool hands to face about and keep off the enemy. He placed

himself at the new head of column, and led the backward move. Out came

the Indians, with shots and triumphant yells, in pursuit. The rear of the

column began to crowd on the head; Reno struck a trot; the rear struck

the gallop. The Indians came dashing up on both flanks and close to the

rear; and then -- then the helpless, horribly led troopers had no alternative.

Discipline and order were all forgotten. In one mad rush they tore away

for the stream, plunged in, sputtered through, and clambered breathlessly

up the steep bluff on the eastern shore -- an ignominious, inexcusable

panic, due mainly to the nerveless conduct of the major commanding.

In vain had Donald McIntosh and "Benny" Hodgson, two of the bravest

and best-loved officers in the regiment, striven to rally, face about,

and fight with the rear of column. The Indians were not in overpowering

numbers at the moment, and a bold front would have "stood off" double their

force; but with the major on the run, and foremost in the run, the lieutenants

could do nothing -- but lose their own gallant lives. McIntosh was surrounded,

dragged from his horse and butchered close to the brink. Hodgson, shot

out of saddle, was rescued by a faithful comrade, who plunged into the

stream with him; but close to the farther shore the Indians picked him

off, a bullet tore through his body, and the gallant little fellow, the

pet and pride of the whole regiment, rolled dead into the muddy waters.

Once well up the bluffs, Reno's breathless followers faced about and

took in the situation. The Indians pursued no further, and even now were

rapidly withdrawing from range. The major fired his pistol at the distant

foe in paroxysmal defiance of the fellows who had stampeded him. He was

now up some two hundred feet above them, and it was safe -- as it was harmless.

Two of his best officers lay dead down there on the banks below; so, too,

lay a dozen of his men. The Indians, men and even boys, had swarmed all

around his people, and slaughtered them as they ran. Many more were wounded,

but, for the present at least, all seemed safe. The Indians, except a few,

had mysteriously withdrawn from their front. What could that mean? And

then, what could have become of Custer? Where, too, were Benteen and Macdougall

with their commands?

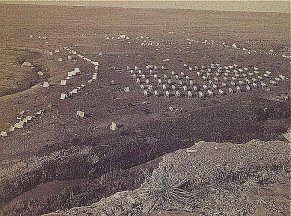

Over toward the villages, which they could now see stretching for five

miles down the stream, all was shrill uproar and confusion; but northward

the bluffs rose still higher to a point nearly opposite the middle of the

villages -- a point some two miles from them -- and beyond that they could

see nothing. Thither, however, had Custer gone, and suddenly, crashing

through the sultry morning air, came the sound of fierce and rapid musketry

-- whole volleys -- then one continuous rattle and roar. Louder, fiercer,

it grew for full ten minutes. Some thought they could hear the ringing

cheers of their comrades, and were ready to cheer in reply; some thought

they heard the thrilling charge of the trumpets; many were eager to mount

and rush to join their colonel, and with him to avenge Hodgson and McIntosh,

and retrieve the dark fortunes of their own battalion. But, almost as suddenly

as it began, the heavy volleying died away; the continuous rattle broke

into scattering skirmish fire, then into sputtering shots, then only once

in a while some distant rifle would crack feebly on the breeze, and Reno's

men looked wonderingly in each other's faces. There stood the villages

plain enough, and the firing had begun close under the bluffs close to

the stream, and had died away far to the north. What could it mean?

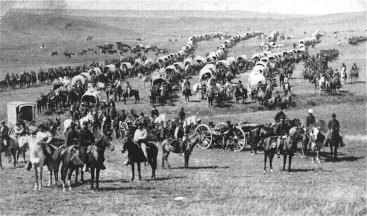

Soon, with eager delight, the little commands of Benteen and Macdougall

were hailed coming up the slopes from the east.

"Have you seen anything of Custer?" was the first anxious inquiry.

Benteen and Weir had galloped to a point of bluff a mile or more to

the north,